|

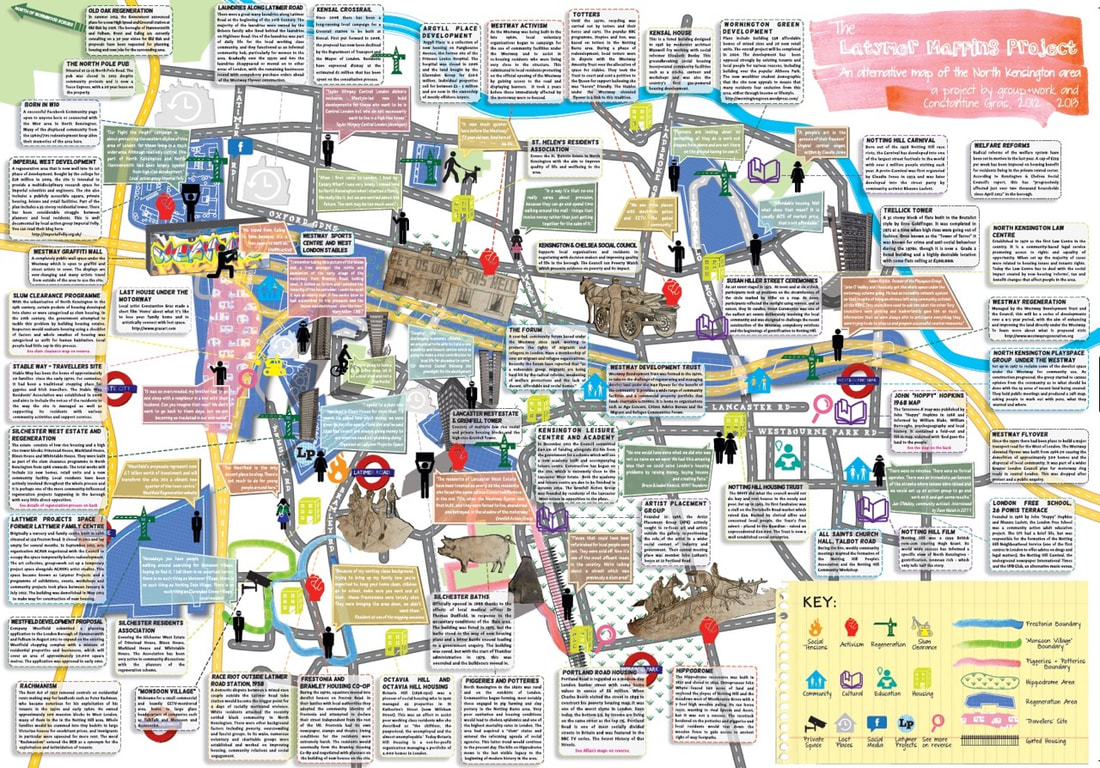

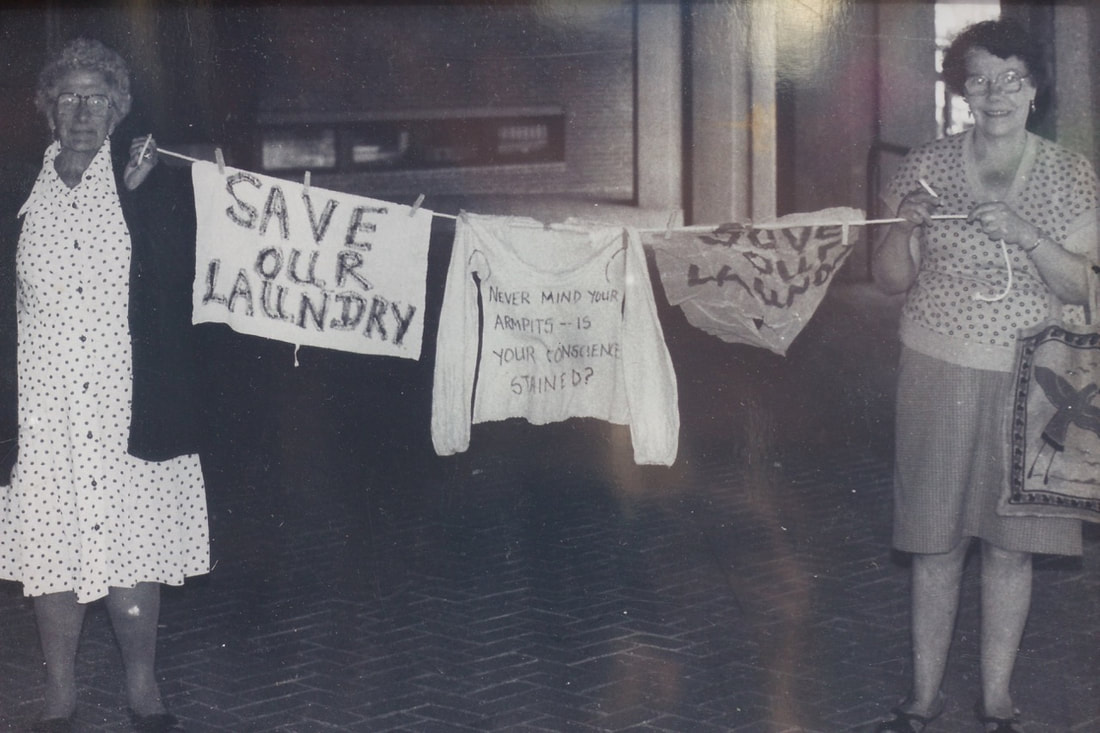

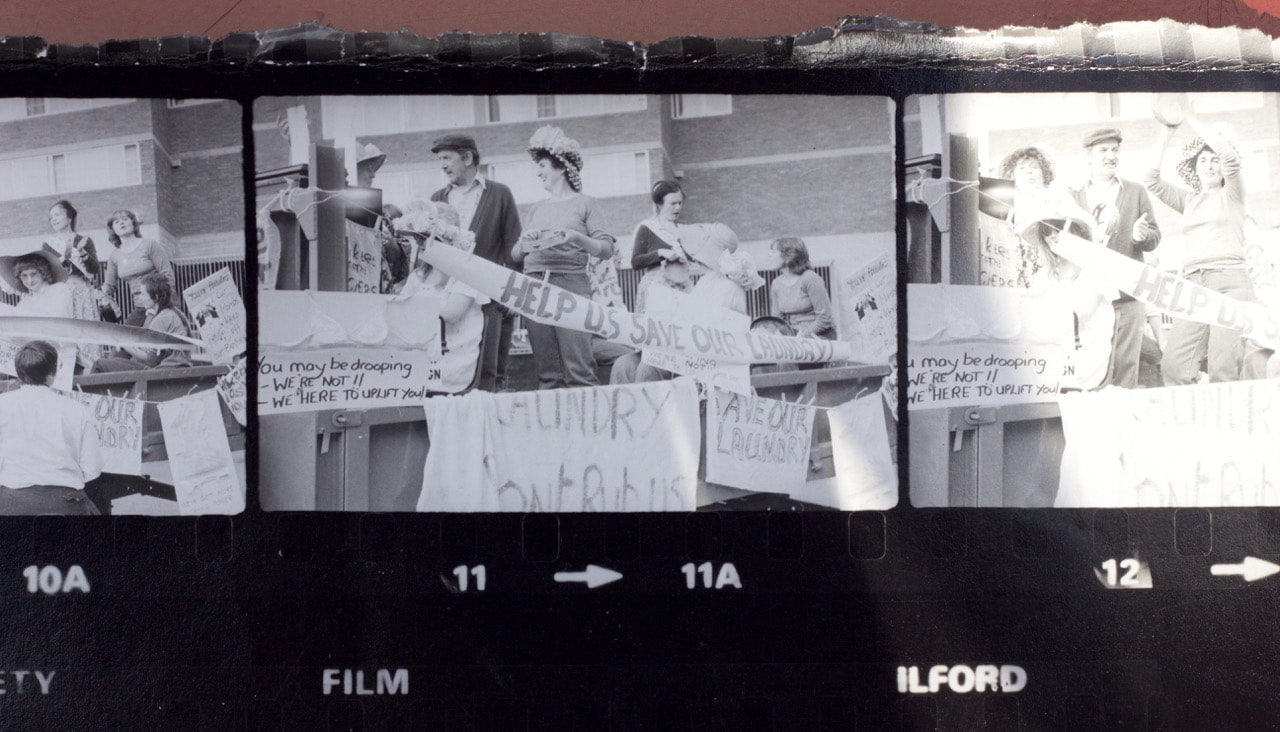

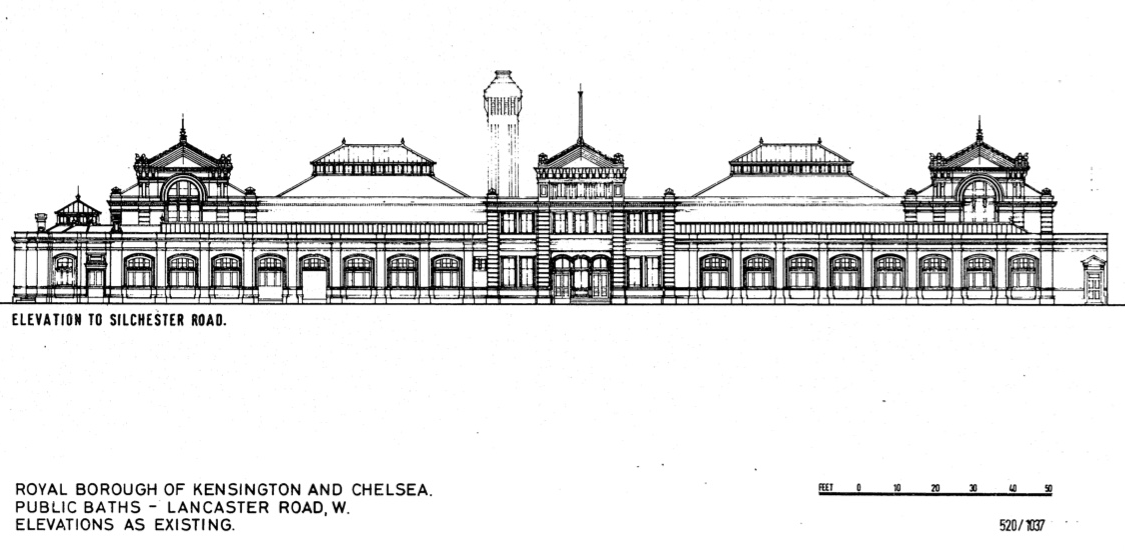

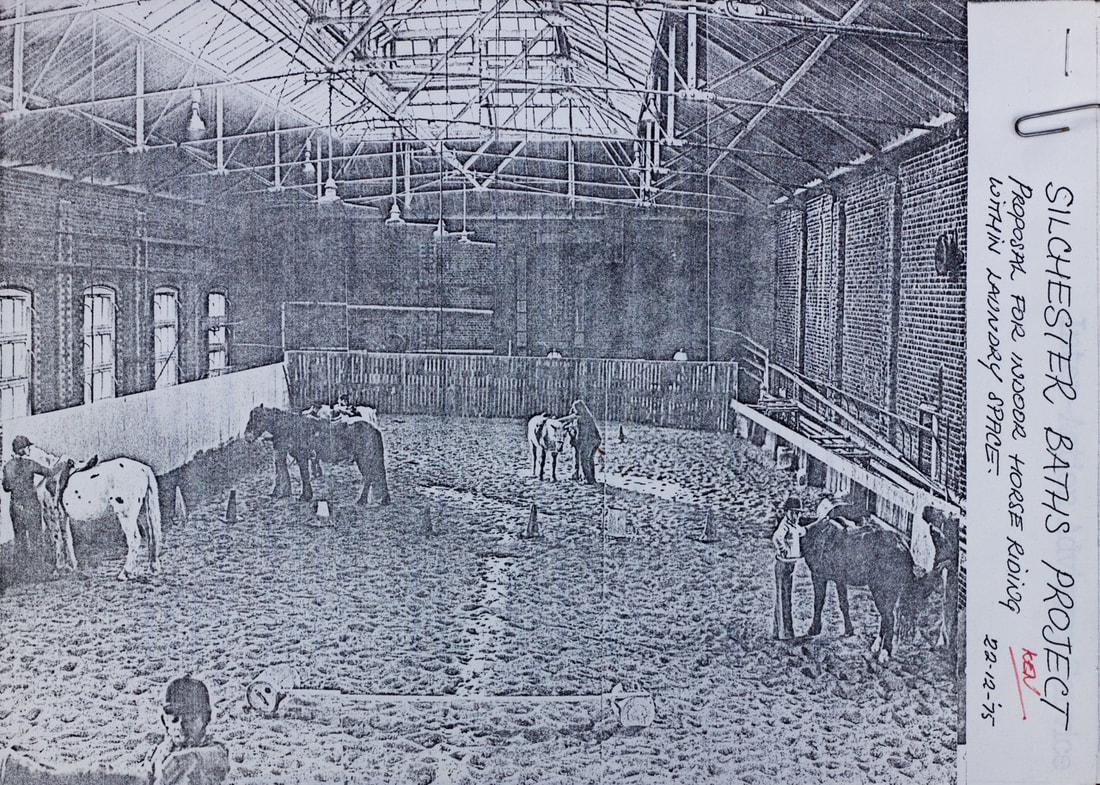

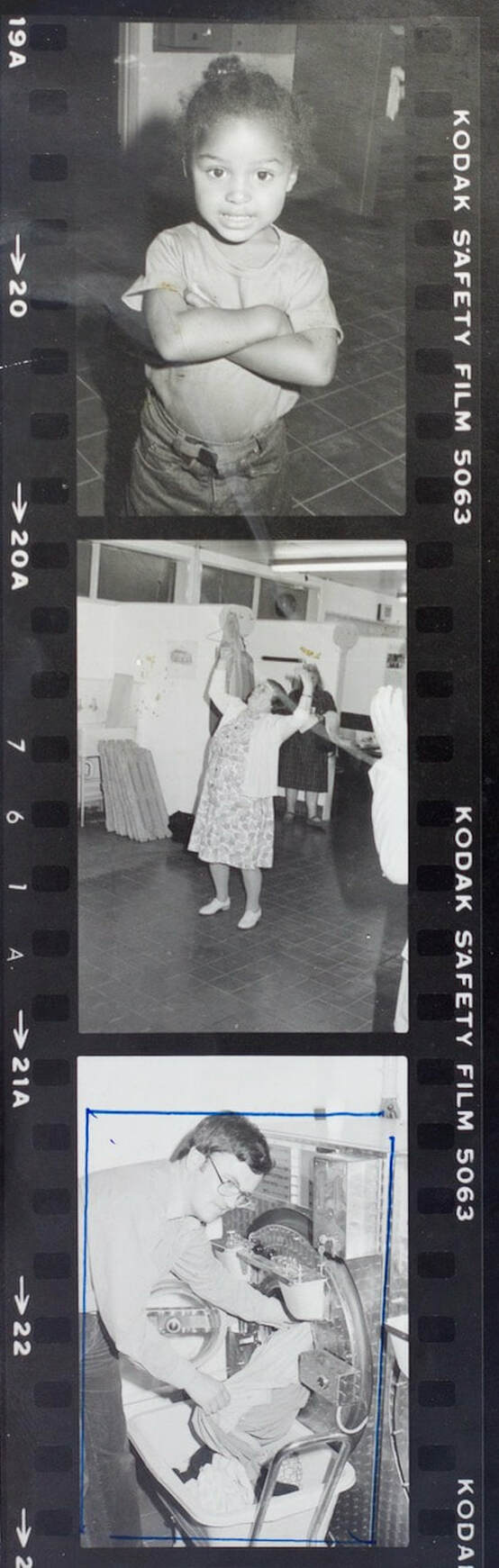

Washing Dirty Linen in Public A performance based walk and exhibition about women's labour and activism in Notting Dale Saturday 27th April at Latymer Community Church, 116 Bramley Road Exhibition display of archive images, drawings and short films from 11am - 5pm Performances also taking place at the church hall throughout the day Guided walks at 10am and 2pm, booking via Eventbrite Walks sold out - please contact us to be added to reserve list Commissioned as part of Hito Steyrl's exhibition at the Serpentine, 11 April - 6 May 2019. When I was visited by Hito Steyerl and staff from the Serpentine Gallery last year, I took them for a walk around the streets of Notting Dale. I explained how housing issues and community activism were captured in a map made during the Latymer Mapping project. Fast forward a year, Hito was preparing for an exhibition at the Serpentine and kindly asked me to recreate the dynamics of the map as a walk. I didn't want to revisit the politics of housing. I thought about using lost or forgotten spaces. Counters Creek that is buried under the streets. A cinematic narrative of historical voices. Each coming together to shed light on contemporary issues; but I needed a focal point. One detail on our original map highlighted the history of laundries in the area. At its peak, there were over 300 workshops and factories in North Kensington supplying cleaning services to the working class households and their more affluent neighbours, as well as hotels and restaurants. As I dipped my toes into the research, the idea formed of connecting the first laundresses of the 1860s with the Silchester Road and Bath House that was built in 1888; and then relating these to the post-war slums and the building of the social housing estates. I envisaged a series of working-class women characters, including recent migrants, who created and then carried on a tradition of women's labour. Many of the original businesses were family run, perhaps with a woman at the helm. Washing could be a capital business and the advent of steam powered machinery was rapidly employed to maximise profit. For the laundresses the work was hard and poorly paid, but could be relied upon at times when extra income was needed for the household. The gathering together of women in this mode of labour created a new social dynamic inside and outside of the home. Becoming an ironer of silk was one of the more specialised roles that entailed better wages. There was a local saying that men of a certain temperament flocked to the area in the hope of marrying and being kept by an ironer. In the archive, there are also early examples of women organising themselves into unions that wanted to improve the working conditions for laundresses that were not fully regulated by the Factory Acts. And also accounts of laundresses taking part in the large labour demonstrations of the 1890s, travelling on a processional float to Hyde Park and getting joyously pissed, dancing and singing, effing and blinding. From this schematic outline, I penned the following characters and they will be performed during the guided walk and at the exhibition on the 27 April: Kathleen Doherty is a migrant from the Irish Famine, who, for a pittance, washes the clothes of the prosperous class in Notting Hill. Looking across the open fields of Notting Dale, she has a comical vision of the future. Florence Smith, 16 years old, already a veteran of the steam laundry workshops, contemplates her adult life as a silk ironer. Freda Palmer is the charwoman who befriends her employer, Margery Spring-Rice and contemplates visiting a birth control clinic that has just opened. Joan Stewart sets off for her weekly visit to wash clothes at the Silchester Road Bath's. It’s no ordinary day: the country celebrates victory in Europe while Joan contemplates the fate of her family. Grace Augustine is a West Indian mum, living in a damp, unfurnished flat, on a road that is about to be demolished for the building of Lancaster West estate. She is visited by her sister Jackie and both are forced to seek sanctuary at the bath and wash house. The monologues and dramatic sketches will be performed by Nina Atesh, Rawleen Evelyn, Shelagh Farren, Rachele Fregonese, Rebecca Hanser, Michelle Strutt and Mina Temple. It was a pleasure to meet up recently with Jenny Williams who told me about her involvement in the laundry narrative. She was raised in North Kensington, worked for the Greater London Council's Women’s Committee and managed children’s services for Lambeth and Camden. She became involved in many of the local community campaigns from the 1960s-80s that addressed the chronic lack of child care facilities and play spaces. As we will discover in the following interview, there are strong parallels between the 1890s laundresses and their 1970s counterparts who saw their beloved Victorian bath and wash house demolished for redevelopment. As a result of effective campaigning, the women were able to get RBKC council to open a new laundry under the Westway. The unglamorous world of soap and suds was the setting for dissent and collective solidarity at a time of profound social change, especially for the elder residents of the community. One of our battles in the 1970s was to try and save the Silchester Road baths and wash house. It was really well used. Mothers who had large families, tended to load up their prams and go to the wash house. You took everything in a great pile and when you came out it was all folded, ironed and you pushed it home. You had your time and day for going. You could be there for three hours and it was very cheap. While you waited, you could buy tea and coffee and bacon rolls. There was a real community aspect to it. That was why there was such an outcry about it. We’re talking about people who had practically been going there all their lives and suddenly the council wanted to close it down. It wasn’t just about losing the laundry. The building had 3 swimming pools at one time: a ladies pool, a gentleman’s pool and a public pool. There were also individual baths and a medical baths centre. When the council announced the closure in 1974, for the continuation of the Lancaster West development, the local women were furious. So it wasn’t difficult to get their support. We even had Max Hastings come to one of our laundry meetings and he wrote an article in the Evening Standard. There were meetings with Cllr. Middleton who I believe was chair of Libraries and Amenities at the time. He said it was rather like Livingstone meeting the savages. We didn’t take very kindly to that sort of remark. The local MP, Sir Brandon Rhys-Williams, was very supportive considering he was a Tory. Also the dust men and Tony Sweeney, the trade union shop steward. I know it wasn’t terribly appropriate, but we got hold of a lorry and took part in the Carnival. That’s me in the middle with the large hat on! Alongside the campaign for retaining a laundry, we got a preservation order on the baths building. Mainly because it was designed by architect Thomas Verity who didn’t usually do municipal buildings. Also it was a nice building. Then various other people got interested in it and put forward these different proposals about how it could be used, including putting a stables in there. Our view was that it should be a community centre and there should be different facilities including a covered market. Then we went to a public inquiry. But the council won in the end. It was pulled down. The council were struggling to get their head around what was happening. Our campaign was just part of a lot of community activism taking place in North Kensington. And we kept telling them we didn’t want a laundrette, we wanted a laundry! The council finally agreed. After the baths closed, they built us a new laundry under the Westway, right next to the Maxilla nursery centre. So we had our laundry which lasted about 5 years. Then in 1980, the council again decided to close it down, So we had another campaign and what the council did was classic. They said to us, why don't you run it! They hand things over, so as not to have anything more to do with it. So we set up a laundry company. Residents wanted to continue to have sinks that they could wash things in and to have access to irons. This service lasted for another 9 years until the machinery started to break down and became too expensive to repair. To be fair to the council, they had actually put in very good quality Miele machines. At this point, the Greater London Council Industry and Employment Committee gave us a grant and we put in a brand new laundry. It was a steam laundry and we had to have a rota of women who managed the boiler. The new laundry was opened by Mike Ward who was the chair of Industry and Employment at the GLC. We told him to bring in his washing for the opening. They supplied us with very expensive machines, the cost for the washer extractor was £5,980 for ten which was a lot of money in those days. Good old GLC! We even had heat exchangers put on top of the dryers, so it was quite economical. The GLC were very interested in green projects. It really was a super service. That lasted for another 5 or 6 years, until again, the laundry machinery broke down. And it was also the time when residents stopped using the service. So our laundry campaign and business started in 1974 and went on into the late 1980s. A lot of us spent many years looking after the laundry, as well as doing other things in the community. Photographs kindly reproduced by Jenny Williams ©

7 Comments

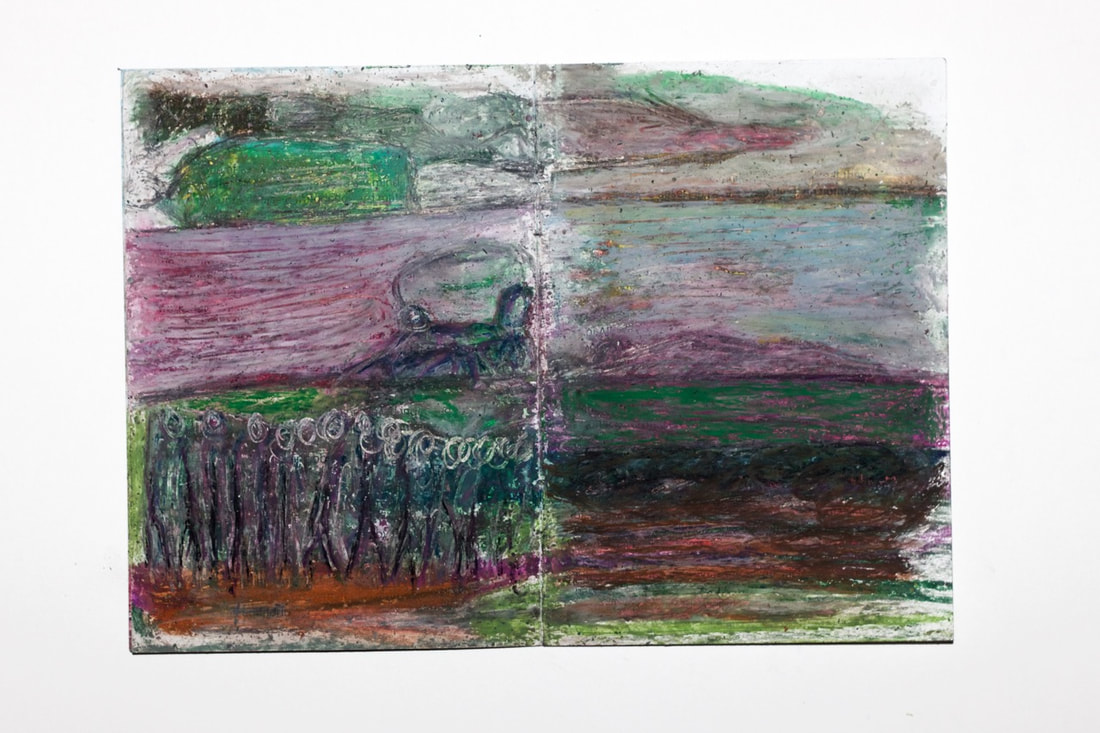

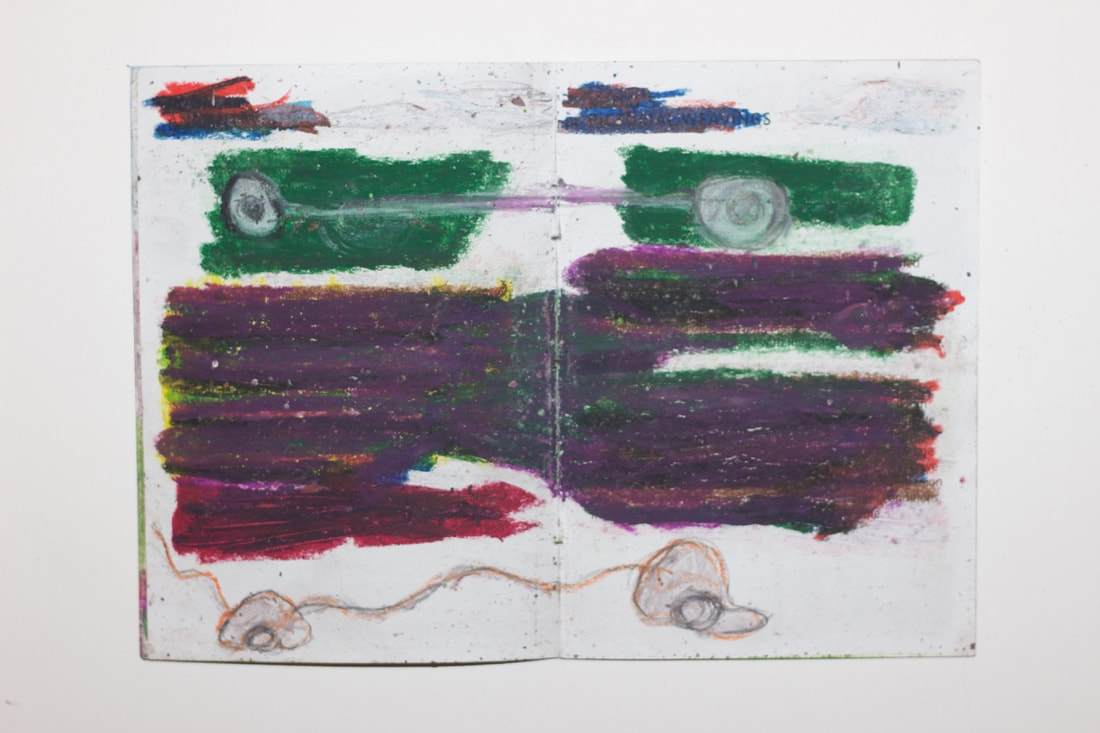

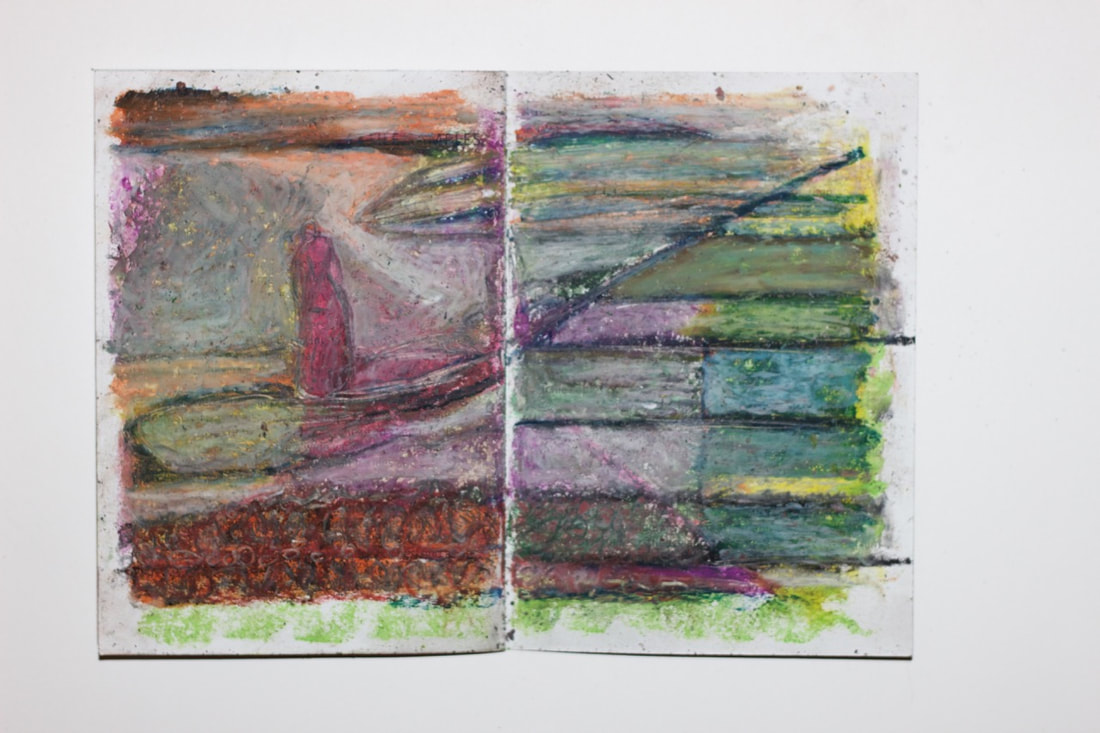

Come, my dear referendum Go deadly cat > apps < bleed the VHS signal The night I buried my passport (in 1973) A suitcase for the deal Euro sting in the Scorpion's Tail The torture of Article 50 What have you done to Therese's voice? Whiplash for the body politic The killer rubber dub (out of sync) Brexit - My Giallo 10.5 x 15cm, oil pastels and pencil 2019 (going on 1973)

Reproduced from Radio Times, 2 November 1934 / BBC Genome

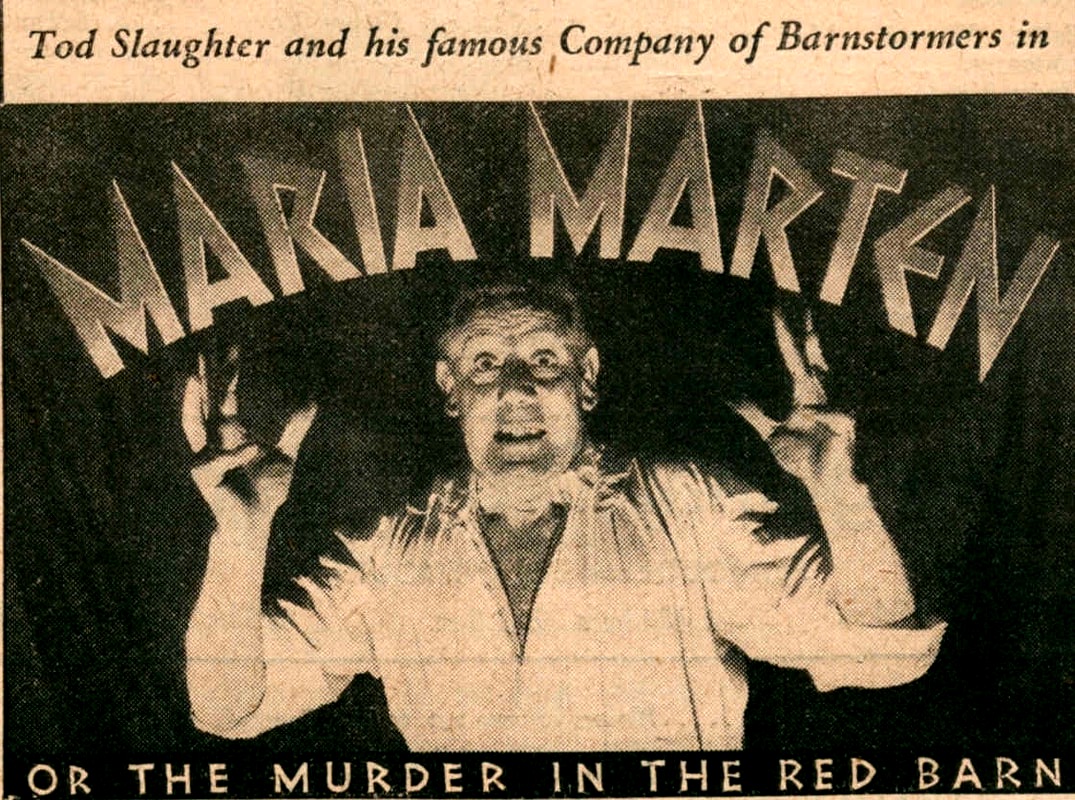

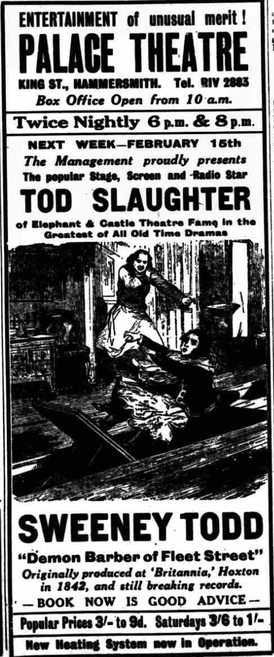

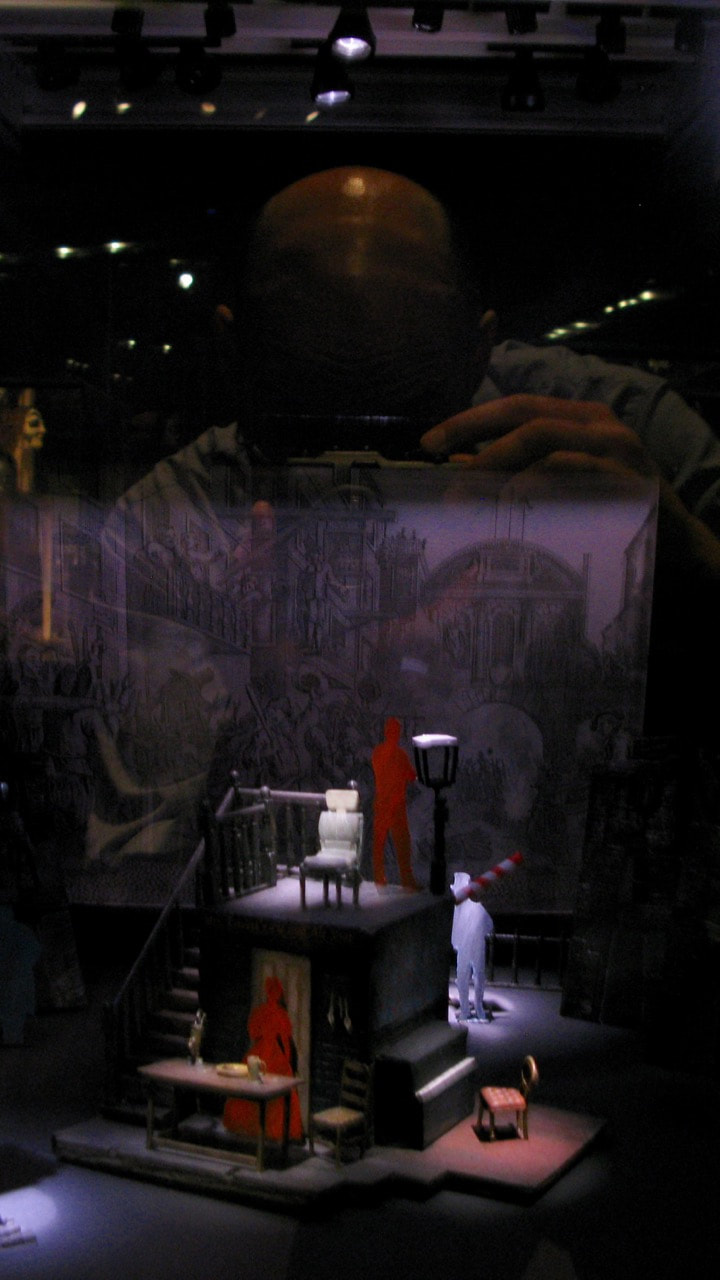

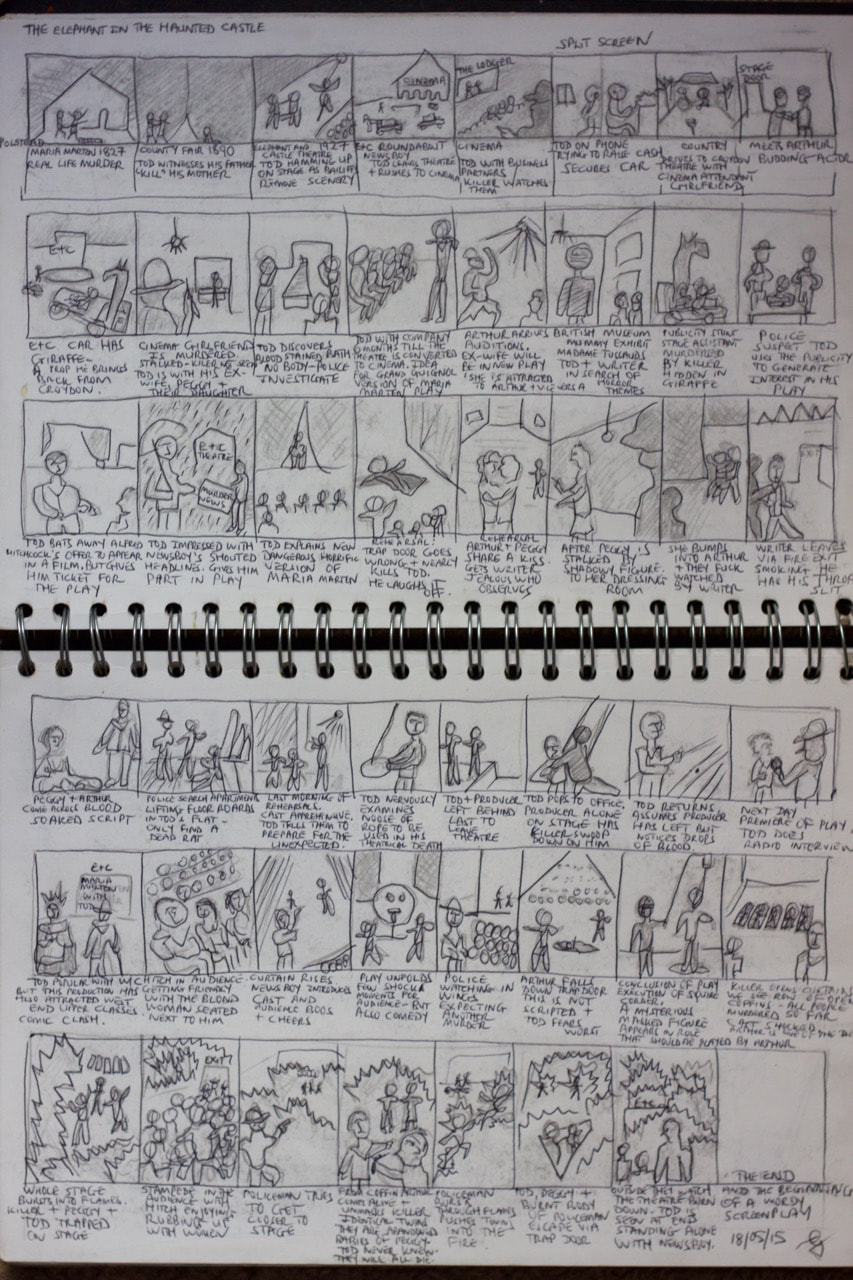

The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle was made in collaboration with John Whelan and People's Company. It told the dramatic story of the Coronet as theatre, cinema and night-club. The project had a curious genesis. It started in 2012, when I tried to remember a film I had seen as a 14 year old, a horror film screened at theABC Edgware Road. The film with its visceral supernatural murders, inspired by Dario Argento's influential shocker, Suspiria, made a deep impression on me at the time. However, over time, I completely forgot what the film was called; while still being able to vaguely recall certain scenes. Decades later, I tracked down the film at Westminster Archives, looking through back copies of newspaper listings. The recovery of that memory as a film called Terror (1978, released in 1981), emboldened me to artistically connect with the lost cinematic spaces and experiences of my youth. My Terror ABC had long been demolished. But I discovered the Coronet in the Elephant and Castle was once an ABC cinema and was being threatened with closure. This was a perfect opportunity to explore my love affair with cinema. The Melodramatic Elephant art project was initially framed around the actor-manager Tod Slaughter, noted as one of the greatest (and greatly under-appreciated) stars of melodrama. He provided a more obvious link to my interests; the intersections where theatre and film, horror and melodrama, meet and diverge. However, I deviated from this focal point when I unearthed the poignant story and medical records of Victorian actress, Marie Henderson. Her life and death, were so poetically linked to the Coronet and her ghostly presence in the building was a perfect medium for threading time across the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. She was also a completely unknown story, while Tod Slaughter was already a minor footnote in film history. I handed over these schematics to John and the People's Company and they created a spectacular last-ever theatrical event for the Coronet. This blog will provide some context to the original ideas for the project and a sample of art work that was generated. In the process, we doff our cap, to the achievements of Tod Slaughter's 50-year career across theatre and film, radio and television. He seemed to be born with melodrama in the blood and was still performing it with relish and abandon, when he died of coronary thrombosis in 1956. Tod had an-end-of-career swan song, impressing the critics and a new generation unfamiliar with the creaky trappings of stage melodrama. A short performance on BBC TV, prompted over 3000 letters asking where Tod's plays could be seen. They recognised the sincerity of his quaint performance in an era that was shifting gears from the Method to the Kitchen Sink. I want to also track-back to Tod's theatrical heyday. We can pin this down to the year, 1927; the last of his three-year tenure as actor-manager of the Elephant and Castle Theatre. He mounted what should have been a routine production of Maria Marten, scheduled to last for one week. Maria Marten or the Murder in the Red Barn was well known to Victorian theatrical audiences and was based on a sensational real-life murder, trial and execution that occurred in Polstead, Suffolk, in 1827-28. Tod's production became one of the hits of the season and was seen by over 100,00o people across 115 nights. The West End audience flocked south of the Thames to witness this old-time drama being presented in a fresh way. I particularly like the reviews that describe the audience: a mixture of the local Southwark working-class, eating oranges and drinking stout, boisterous in their interaction with the performers; while seated cheek-by-jowl, with the mannered ladies and gents, using viewing glasses to scrutinise the on and off-stage shenanigans. You can imagine a humorous culture clash. This was a moment of significance: melodrama being resurrected in a theatre that was on the brink of conversion to a cinema. All this research was percolating in my mind, unlocking a range of cinematic ideas and storyboarding.

The West London Observer, 1943

Newspaper image © Successor copyright holder unknown. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk Set model box for Sweeney Todd, 1993 V&A Museum

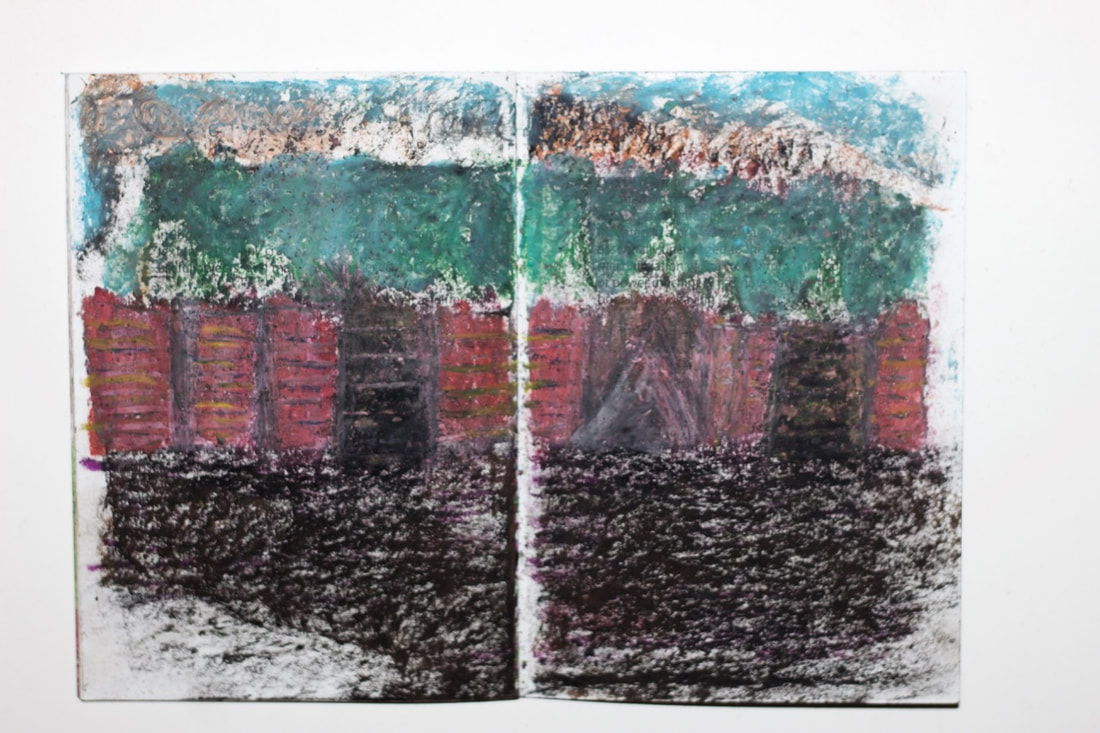

Sketch 1 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod watching Hitchcock's The Lodger (1927) while being stalked by a serial killer 22 x 30 inches, Oil pastels, 2013

Sketch 2 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod as William Corder in Maria Marten being directed by serial killers 22 x 30 inches, oil patel, 2013

Sketch 3 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod, seated, watching the burning of the Elephant and Castle Theatre 16.5 x 23 inches, oil pastel, 2015

Narrative storyboard for The Elephant in the Haunted Castle, 2015

Tod became a minor British film star of the 1930s and early 40s, often appearing in adaptions of his stage plays. These "quota quickies" were made on shoe-string budgets. Modern audiences would grudgingly call them camp but cheerful. Film scholars have analysed certain films in terms of their social dimension, the themes of capital and labour. In terms of performance, Tod is ripe and fruity in his portrayal of villainy. One moment, the patriarchal squire, lusting after a country wench. The next, with his yeast in the bun in the oven, he chuckles before "polishing" the wench off to an unmarked grave. This is all set within a narrative that has basic motivation and plotting; however, this brings me reassuringly, full-circle, to the Terror I witnessed at the ABC that exhibited similar tropes. I'm not sure how accurate the press releases were in describing Tod as Europe's first horror star. The Face At The Window (1939) is a rare example of melo with "horror" motifs. I don't think the conventions of horror meant anything to Tod. He was not the director of any of his films, whereas he was fully in control of all the theatrical productions. You get a better sense of the quality of these when you listen to a radio broadcast or a vinyl pressing. The films are also more truncated and diluted for the Board of Censorship: at the end of the film version of Maria Marten, the hanging of William Corder is off-camera; a more explicit sequence had been shot but did not find its way into the final print. Also of interest is Tod's theatrical productions of Spring-Heeled Jack. In the play, Tod plays the villain lurking in the trees of Epping Forest. He then swoops down to plunge a hypothermic syringe into the leading lady and chuckles over "Two and half pints of lovely blood." I'm not sure what Jack was planning to do with the blood. Is this a plot where our beloved NHS is transfused by the private sector of blood merchants? We have comic accounts of Tod wearing a harness under his costume, attached to wires and being yanked up into the fly loft by the stage crew; springing in and out of scenic trees and occasionally just left dangling in mid-air when something went wrong. Melodrama, horror, comedy - all rolled into one! Let's leave the final image and word with Tod as Sweeney Todd. In total, he played this role over two thousand times. At the end of most productions, there would be a speech and then an invite onto the stage for anyone who was tired of life. Does anyone want to try the murderous barber's chair for comfort? Tod was ever the practical joker. Not many took up the challenge. However, one day, as recounted by Tod, a man came forward, saying he had a row with his wife and was sick of life. So he sat in the chair and was about to be thrown under the trapdoor and onto the mattress beneath the stage, when his wife shouted out from the auditorium. No, don't do it! The quarrel was settled and their relationship patched up (we would like to think!). This is almost a comic form of melodramatic therapy. It also neatly illustrates how the audience had a very direct emotional connection to the world of Tod. "It is grand to be playing at the Hackney Empire again (in 1954) before I pass into the limbo of forgotten things." Tod is in the limbo of things. He is not forgotten. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed