|

Over the past decade, I have had the unique experience of working with residents and the diverse communities on three social housing estates in North Kensington: Silchester Estate, Lancaster West Estate where Grenfell Tower is located, and, in the past few years, Wornington Green Estate. It has been challenging but has resulted in a rewarding body of work across multi-media, with film making always at the core. The bitter and sweet fruits of this labour come into sharp and public focus in the coming week.

On Wednesday 8th September, Grenfell: The Untold Story will air on Channel 4 at 10pm.

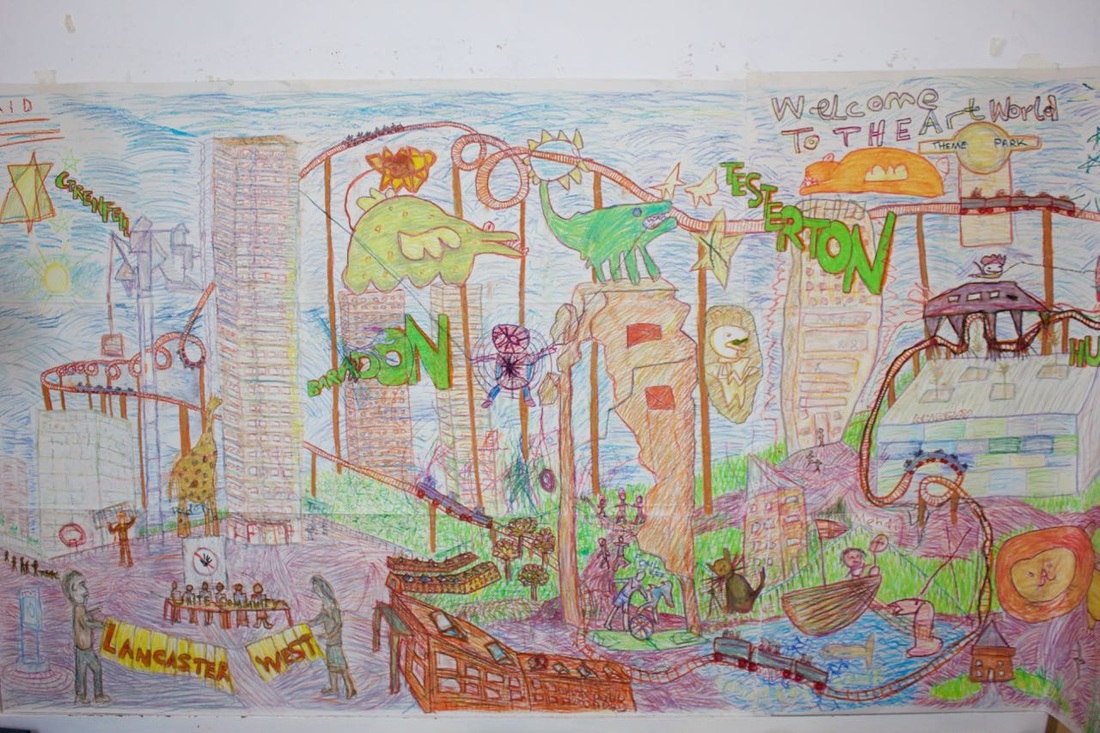

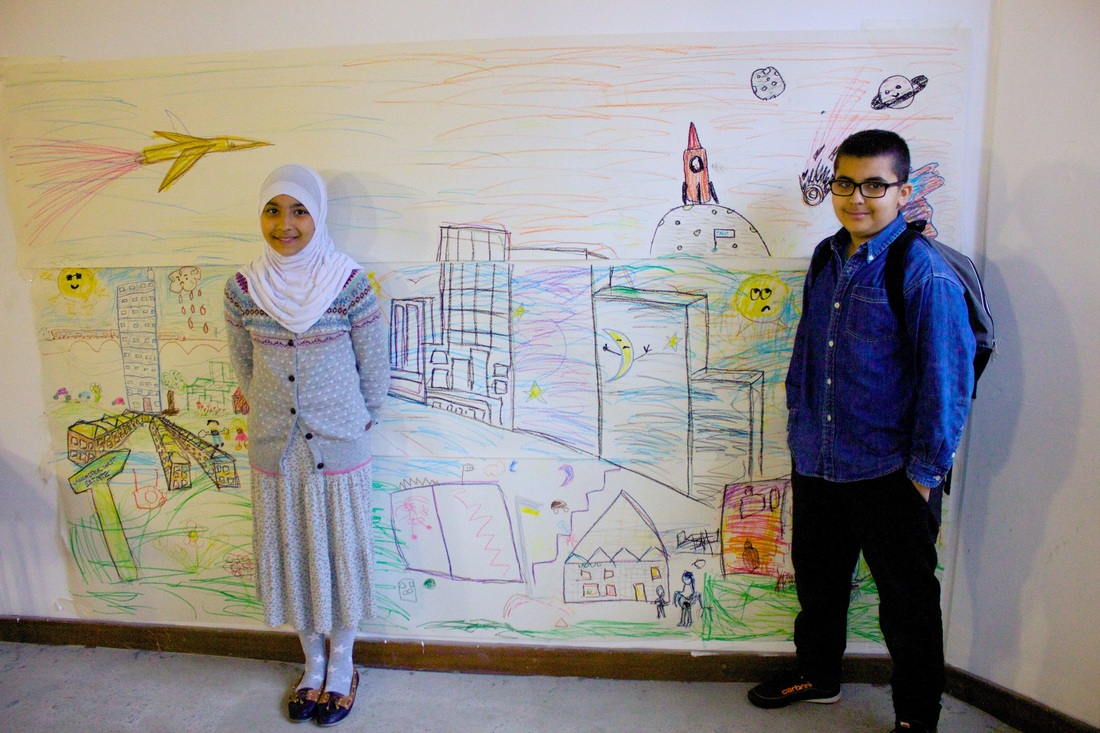

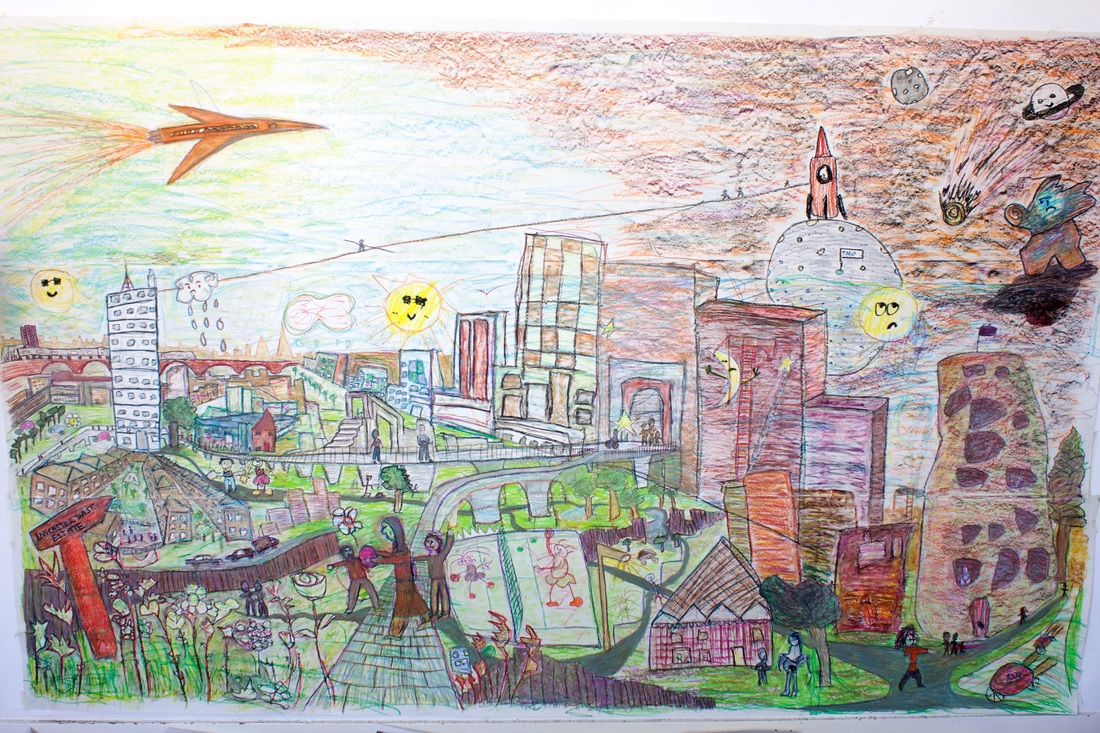

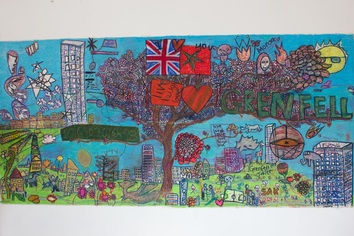

Before the tragic fire, I documented the struggles of Grenfell residents who raised issues and concerns about the work being carried out. Using footage never previously seen, this film forms a prequel to the disaster casting the tragic story of Grenfell in a new light. I've been holding onto film footage and photographs for over 4 years. It was handed over to the Metropolitan Police a month after the fire and over the years was made available to various members of the bereaved and survivors. Now that the police have cleared my use of the footage, it's the right time for it to be shared in a powerful documentary made by director and producer, James Newton and Daisy Ayliffe.. What were the circumstances that lead me into becoming an artist "in residence" at Grenfell Tower? I am deeply interested in the social aspect of art and the political issues this entails. In 2010, I made a commitment to working in and around the two estates of the Notting Dale ward in North Kensington - Silchester and Lancaster West. This patch of land has a fascinating and troubled history from slum housing to race riots. The estates that were built in the 60s and 70s were undergoing controversial redevelopment and this allowed me an opportunity to connect and explore. A nursery being closed down. A row of social housing on Shalfleet Drive was about to be demolished. Why and how were these taking place? It meant creating art that really connected with local residents. I may have been naive in approach, but not feeling. And it was based on this experience as a community-based artist and being employed by the V&A Museum as their first (and only) community artist in residence, sited in a council house about to be demolished for the More West development, that I caught the attention of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO). In 2015 they contracted me to make a short promotional film and large scale art work for Grenfell Tower as it was being renovated. I worked on this project for approximately a year. Early in my engagement, I made a decision to deviate from my contract and make a feature length documentary that ended up being called The Forgotten Estate. This was based on interviews with six residents who lived on the estate, in addition to the original architect and estate inspector. It was an attempt to use film to facilitate mediation and shared understanding between the TMO and residents who were in deep dispute over the impacts of the building works. The residents asked me to film meetings and a Fun Day. The TMO told me I would not be paid for this. The TMO never adequately engaged with the film I made seeing it as the same tired old voices that offered nothing new and marketable for them. I subsequently delivered a short 10 minute film to the TMO that featured no residents but portraits of the Boxing Club and Nursery that had moved back into new premises in the tower. I have only screened The Forgotten Estate on several occasions and have now withdrawn it from public viewing. The art work that I was commissioned to make also had a frustrating outcome. The TMO never hung up the completed work in the Tower and so it was not destroyed in the fire. It now resides in the offices of Grenfell United and a copy in the Houses of Parliament. Grenfell: The Untold Story will powerfully illustrate through the voices of residents, how a £10 million refurbishment that resulted in flammable cladding and insulation being installed, failed to meaningful engage with the desperate concerns of residents and the tragic consequences that resulted. The causes of the Grenfell fire are complex and multi-factorial. But this lack of engagement and duty of care to the residents was a significant failure. I hope that this film will have an emotional and soul searching impact on the wider public, politicians, local authority, architects and the building industry. Also on Wednesday 8th September a short film called A Spell For Wornington Green, was released by Channel 4 on the Random Acts platform. The film was shot over 2020-2021 during the Covid lockdown on Wornington Green Estate in North Kensington and follows the life cycle of two baby pigeons and the subsequent coming together of the community in direct action to prevent the felling of 37 trees as a consequence of urban regeneration by Catalyst Housing. Wornington Green Estate is half-way through a 20 year regeneration into Portobello Square. Nick Burton, who survived the Grenfell fire but sadly lost his wife, witnessed the felling of these trees on 1st March 2021 and commented: “My wife is dead because of Grenfell and they still won’t listen to the community.” Whereas at Grenfell, where I very much remained behind the camera or sketch book, I have since taken more direct action and set up the campaign group Wornington Trees. We are challenging the mass felling of mature trees in one of the most polluted parts of London. We have a second petition presented to the Council that was signed by nearly 2000 residents. It calls on RBKC to compensate us by planting an Urban Forest in North Kensington and to stop Catalyst Housing from cutting down any more trees until they have consulted. The regeneration of Wornington Green into Portobello Square involves knocking down and rebuilding 500 flats to rehouse its original community, plus the building of another 500 more at market rent or sale, where a one bedroom flat costs £700,000. The lack of real consultation and the resulting loss of green public space and the felling of 100's of trees during a climate emergency is the most deplorable part of what was once deemed a "flagship" regeneration by the Mayor of London.

Filming by Ilaria Di Fiore and music by Taozen.

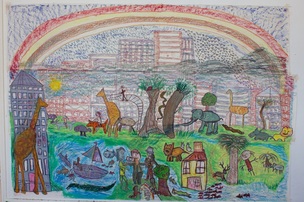

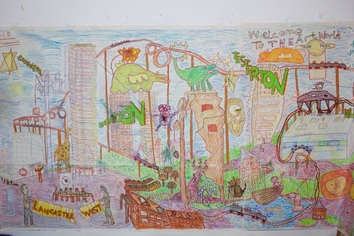

This summer at the pop-up Portobello Pavilion in Powis Square, I displayed several large scale drawings from a series called Wornington Green in Black and White. They tell the narrative story of Wornington Green Estate.

Drawing 1: The Squalor of Wheatstone on Screen

Charcoal 2019 This is based on a newspaper article from 1975 that described how a local resident, Mrs Leq-Roy, borrowed a video camera and made a 20 minute documentary about the infestation of mice, dilapidated ceilings, rotten 'death-trap' flooring and overspill urine running down the walls of the houses on Wheatstone Road. Residents were calling for their slum houses to be pulled down for redevelopment.

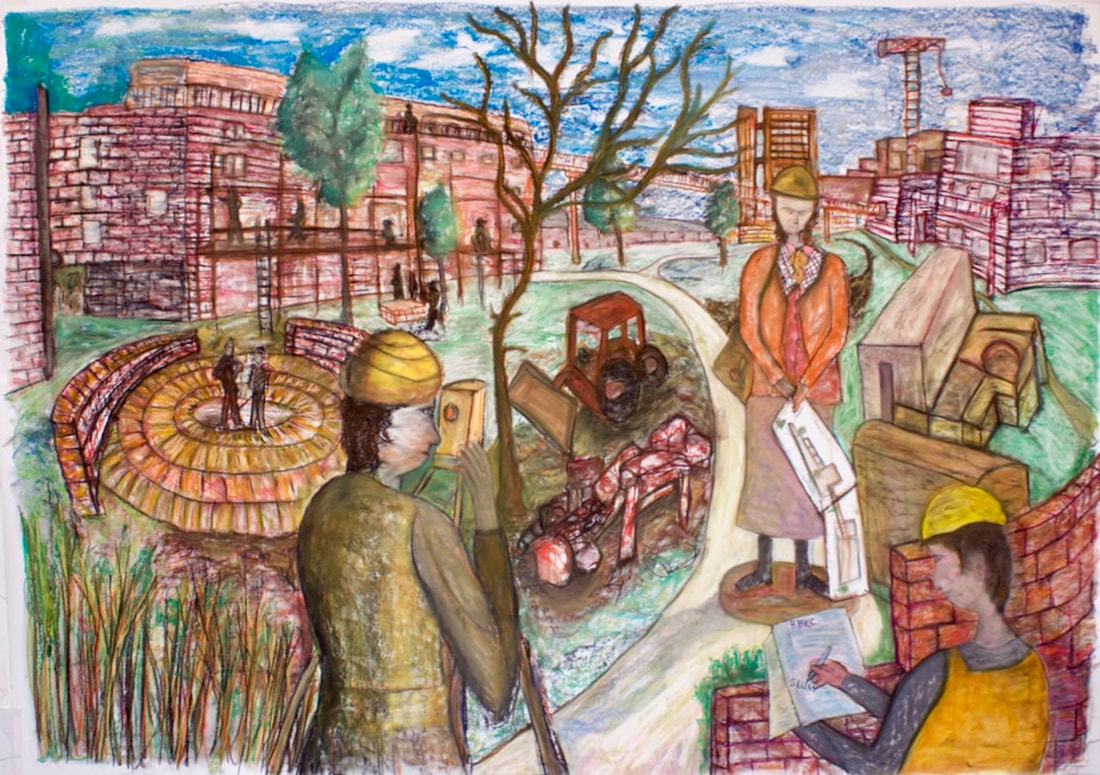

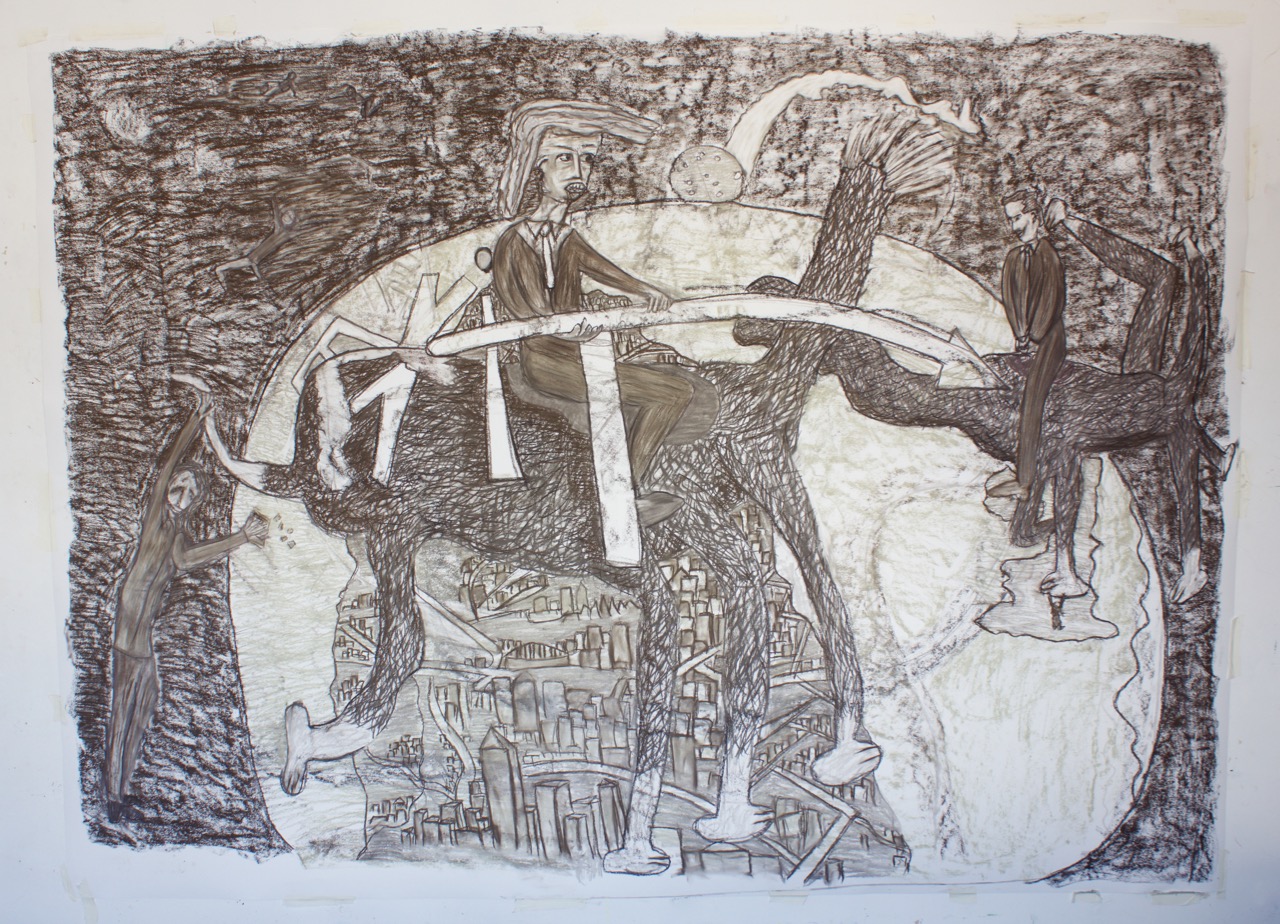

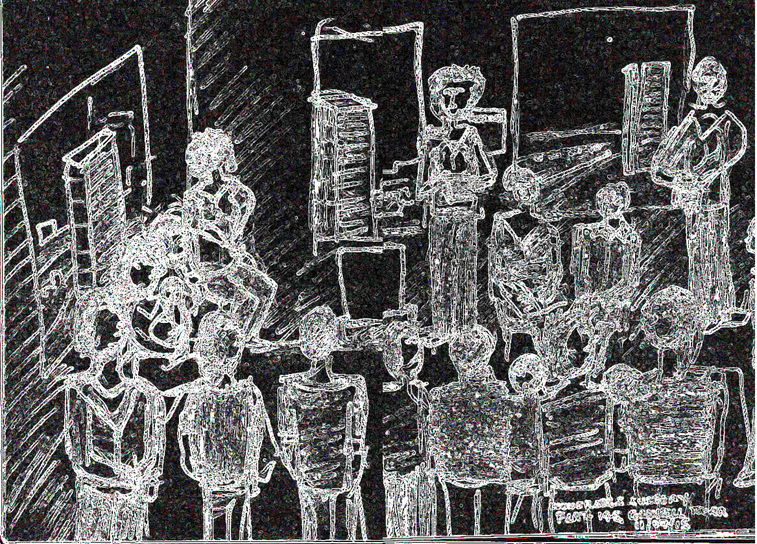

Drawing 2: The Whole Scheme represents a 21st Century Slum

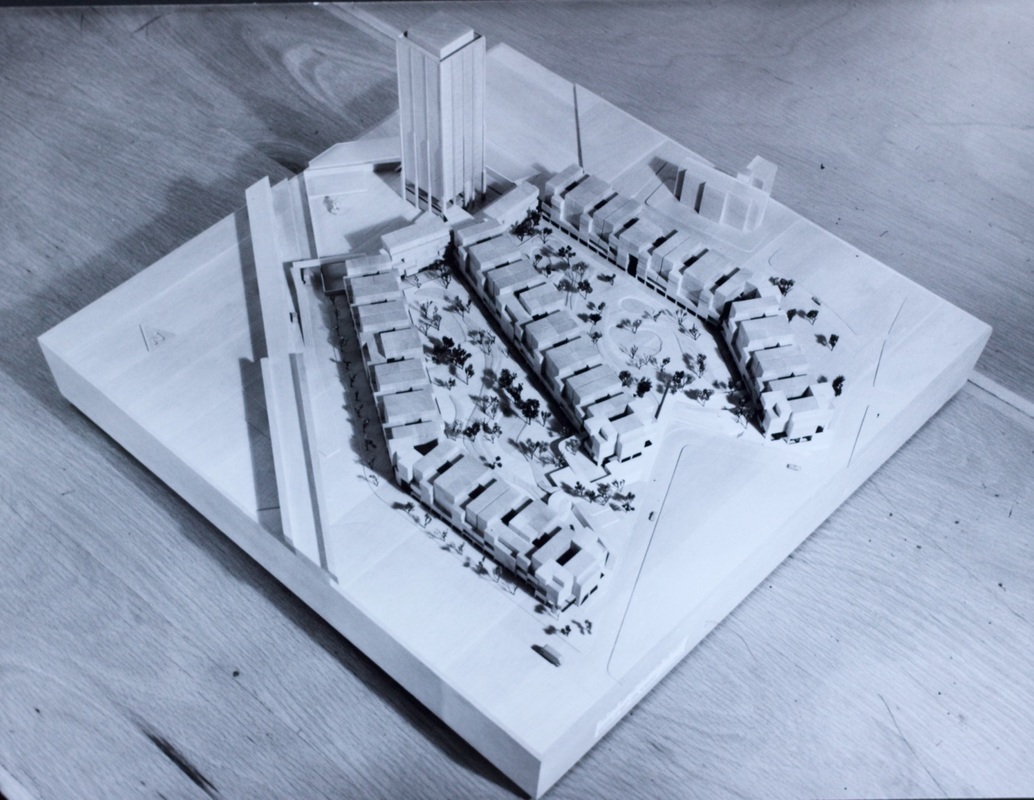

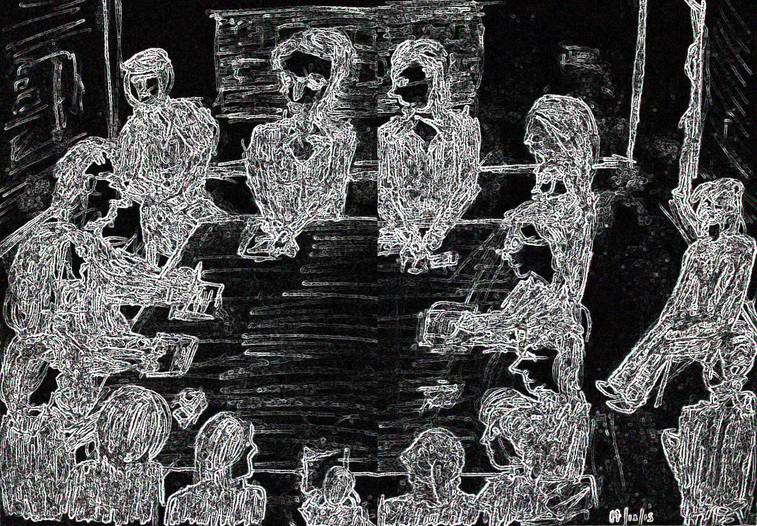

Pastels 2019 This illustrates the lead architect for Wornington Green Estate, Jane Durham, as she oversees the building of the Murchison Road Development that became Wornington Estate. Also present are representatives from the Council's Housing Department. One of whom, in archive records from 1975, stated: "Having had the unique opportunity of being able to view a finished block, it should be obvious that it is an architectural disaster and to repeat this form all over North Ken will be a Planning Disaster! The whole scheme represents a 21st century slum."

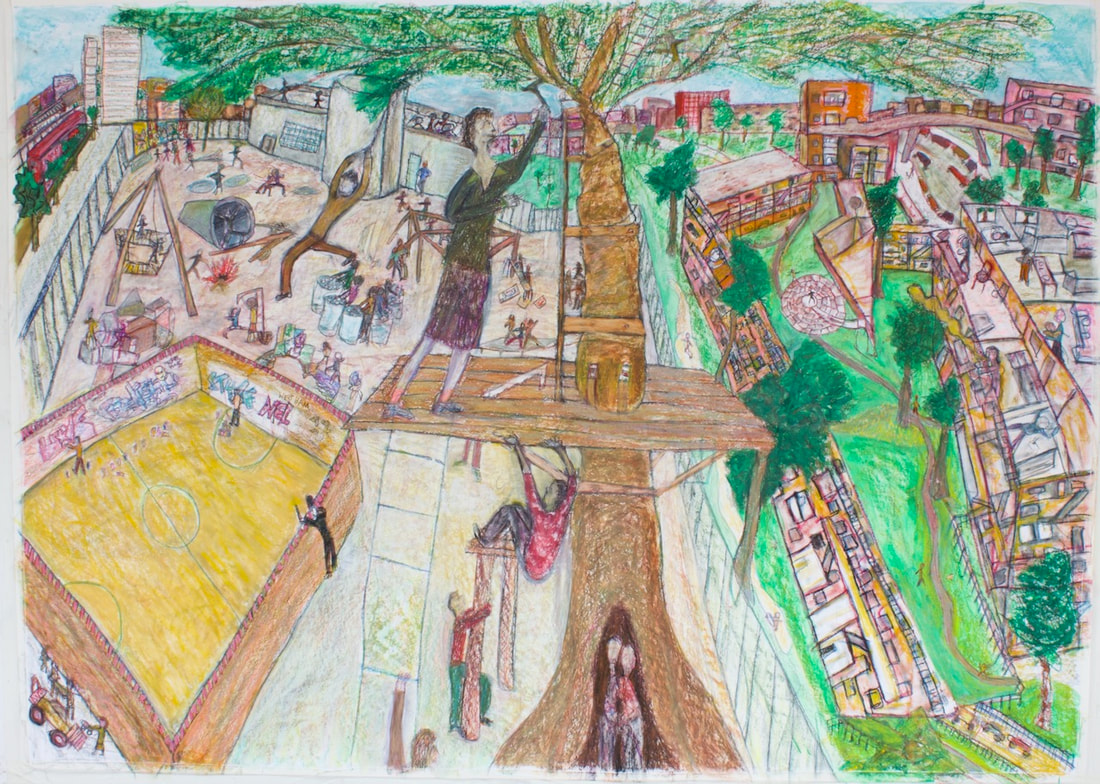

Drawing 3: Building a tree house at Venture Centre

Pastels, 2021 This drawing takes its inspiration from Wornington Word, a heritage project, that documented the voices of residents on the Wornington Green estate. In particular, an audio recording made by brother and sister, Latifa and Rachid Kammiri, who grew up on the estate and played at the nearby Venture Centre (the oldest standing adventure playground in the UK). "It was beautiful living here, it was absolutely the best thing ever, I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else because you were always safe. And we had the Venture playground right next to us which was totally different. Filthy yes because it was just all – it wasn’t even mud, was it, it was just like black dust everywhere. Our parents never used to like us to go there for that reason, you know, because you’d go there clean and come back like mechanics. But it was great. I think what I liked about it most when you went in there, it wasn’t health and safety, you just did what you wanted to do. You had to build your own activities, your own swings, your own slides, you know, from scratch. We literally built the Venture playground together." Footnote: the historic Venture Centre is scheduled for demolition during Phase 3 regeneration of Wornington Green and will be relocated in new premises in Portobello Square. Drawing 4: The great storm of 1987 Charcoal, 2021 This is based on another archive record and a recent telephone conversation I had with Margaret Cairns-Irven. She moved into Watts House on the estate in the early 1980s and described having central heating for the first time - "It was like it hugged us." At this time, the trees on the estate were in full bloom and while a keen gardener and nature lover, Margaret recollected that there were just too many in close proximity and the roots of one had grown into her garden making it difficult to plant anything. The drawing also includes a recollection she made about the Great Storm of 1987. During the night, corrugated sheeting had been ripped off the roof of the Venture Centre and flew over Watts House and she observed the frightening scene of a tree being blown down the middle of Wornington Road at 40mph. But humorously commented - how it was well driven and managed to avoid all parked cars!

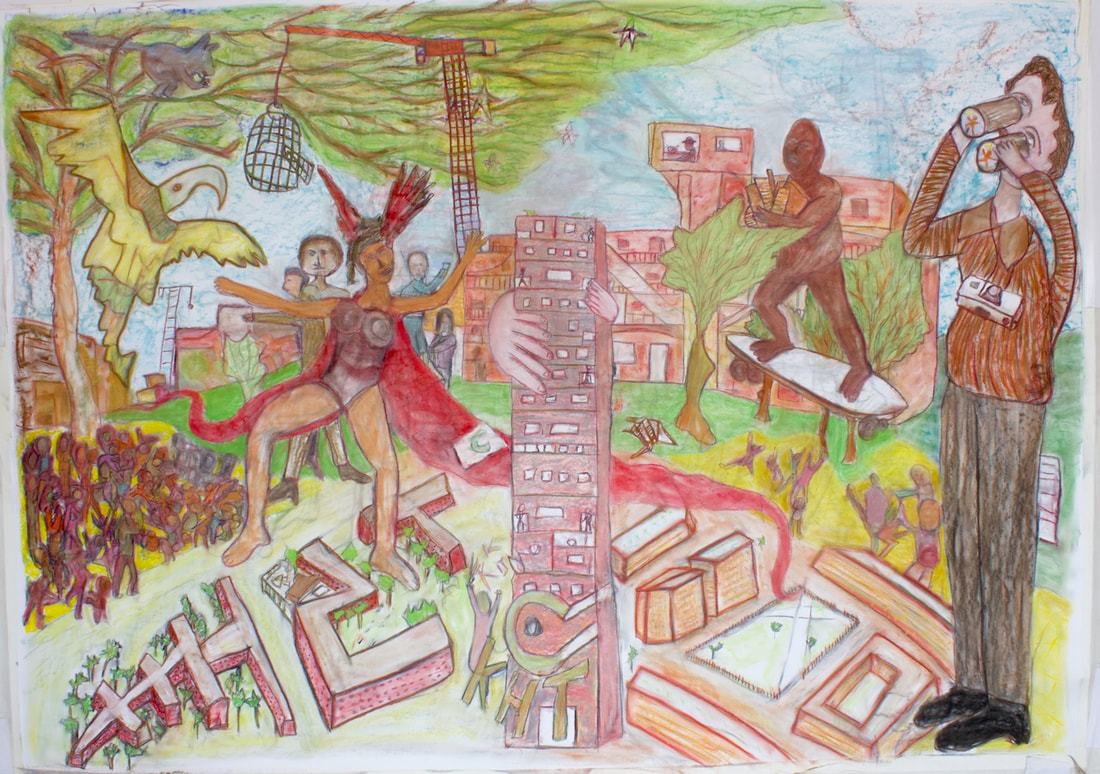

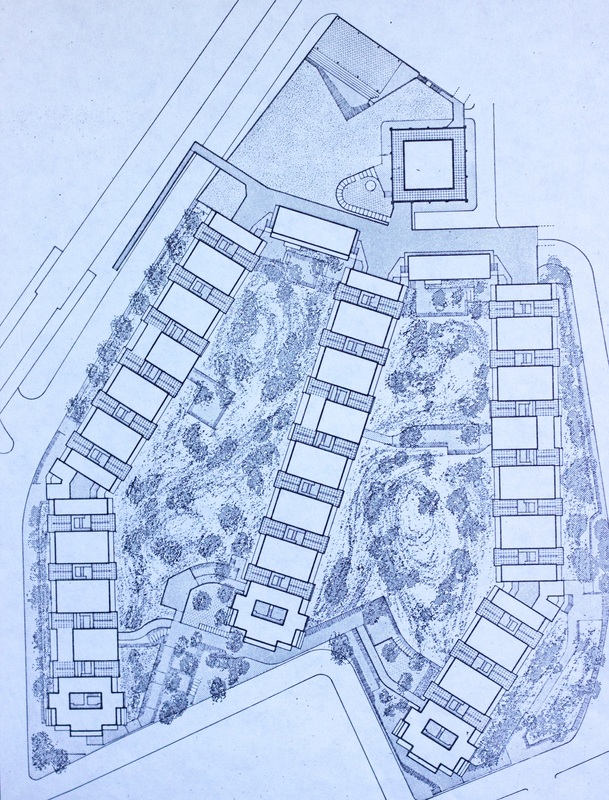

Drawing 5: Resident lead regeneration 1990 and Kensington Housing Trust / Catalyst led regeneration in 2010

Pastels, 2021 This drawing fuses together past and present regenerations on the Wornington Green estate. In 1990, the residents worked with Kensington Housing Trust to upgrade and install security entrances across the estate. In the archive, a resident newsletter had the optimistic and comedic image of King Kong proudly clutching the new security entrances. In my drawing Kong is bursting through the trees with joy. On the bottom of the picture plane, you can see the original estate with its interconnected blocks and walkways (left channel) alongside the 2010 Masterplan for Portobello Square (right channel). The contemporary architects plan to return the traditional street pattern made absolutely no attempt to build around and incorporate trees into the design. There are several other sweet notes and off-beat flavours in the image. These include the dancing and frolics of Notting Hill Carnival revellers. And the bird-watching of Keith Stirling. He is a life long member of the estate, who had campaigned for decades against the lack of maintenance and proactive management. Keith would resign from the Residents Steering Committee in 2020 in protest of Catalyst's plans to fell 42 mature trees and this inspired me to join him in taking our first petition to the Town Hall.

Drawing no 6 - March 1st, 2021.

Pastels, 2021 This drawing illustrates the coming together of the community to protest the felling of 33 trees on Wornington Green estate in March 2021. Two women from our community were arrested. Film of this features in A Spell For Wornington Green. I am planning a gallery exhibition of all 6 drawings.

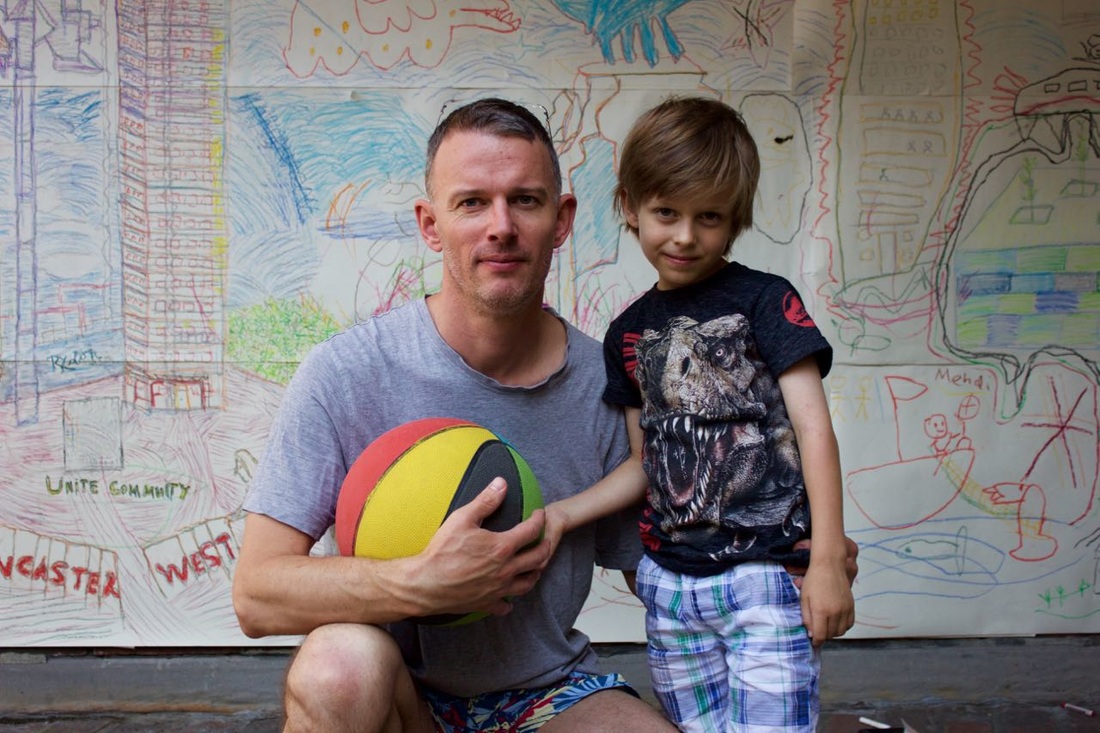

On Saturday 11th September, from 11.30-2pm in Waynflete Square on the Silchester Estate, the Residents Association are holding a public meeting with the Council to share ideas about the future of the estate and how to spend the Grenfell Housing Legacy fund. At the same time in Waynflete Square, we are holding a launch event for the Art For Silchester book that was postponed by the Covid pandemic. This was an arts project I ran from 2018-20 for residents of the estate. Please drop by and see our amazing book and art work. Silchester Estate was earmarked for complete regeneration with the loss of its lovely green spaces. It was only the Grenfell fire that stopped RBKC council from carrying this out. Please visit the lovely square with its beautiful trees.

0 Comments

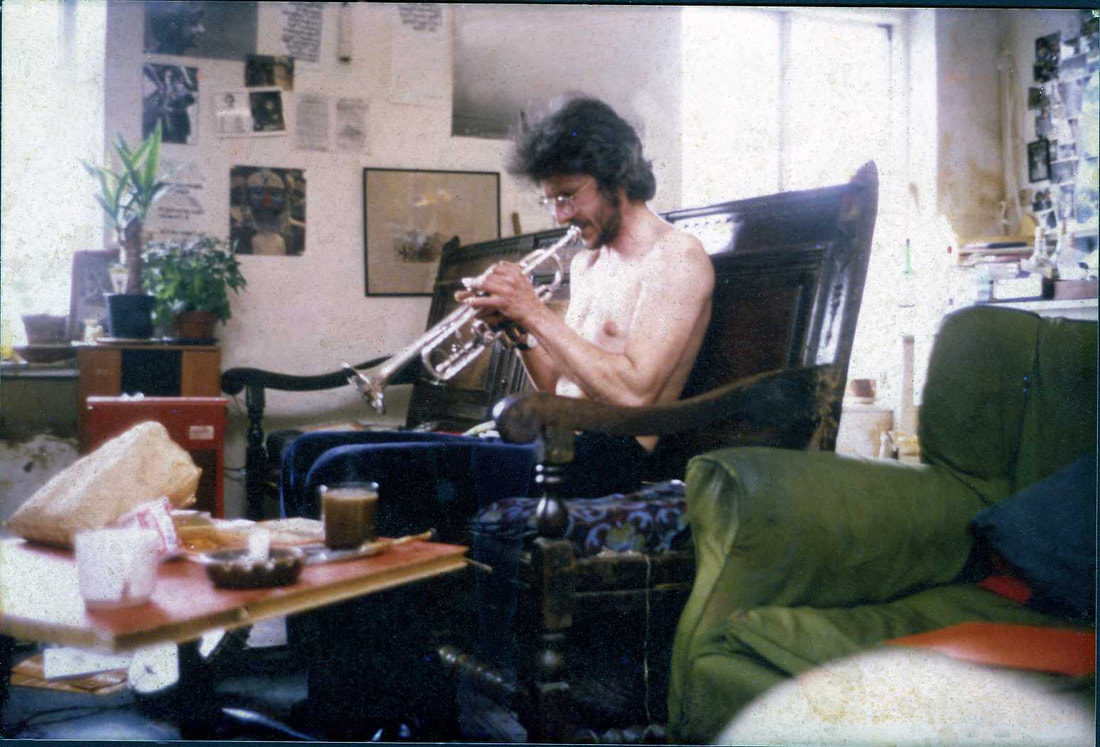

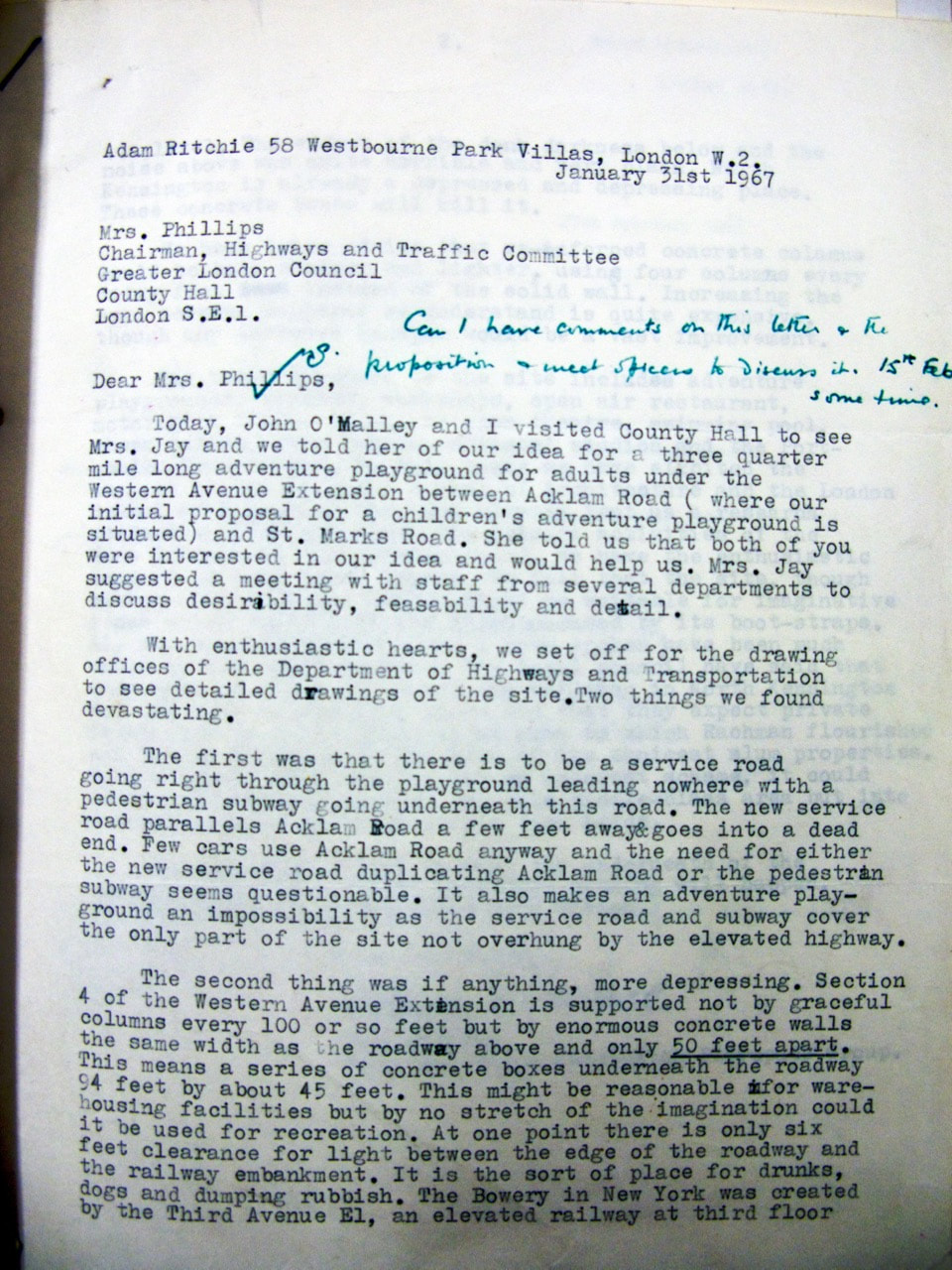

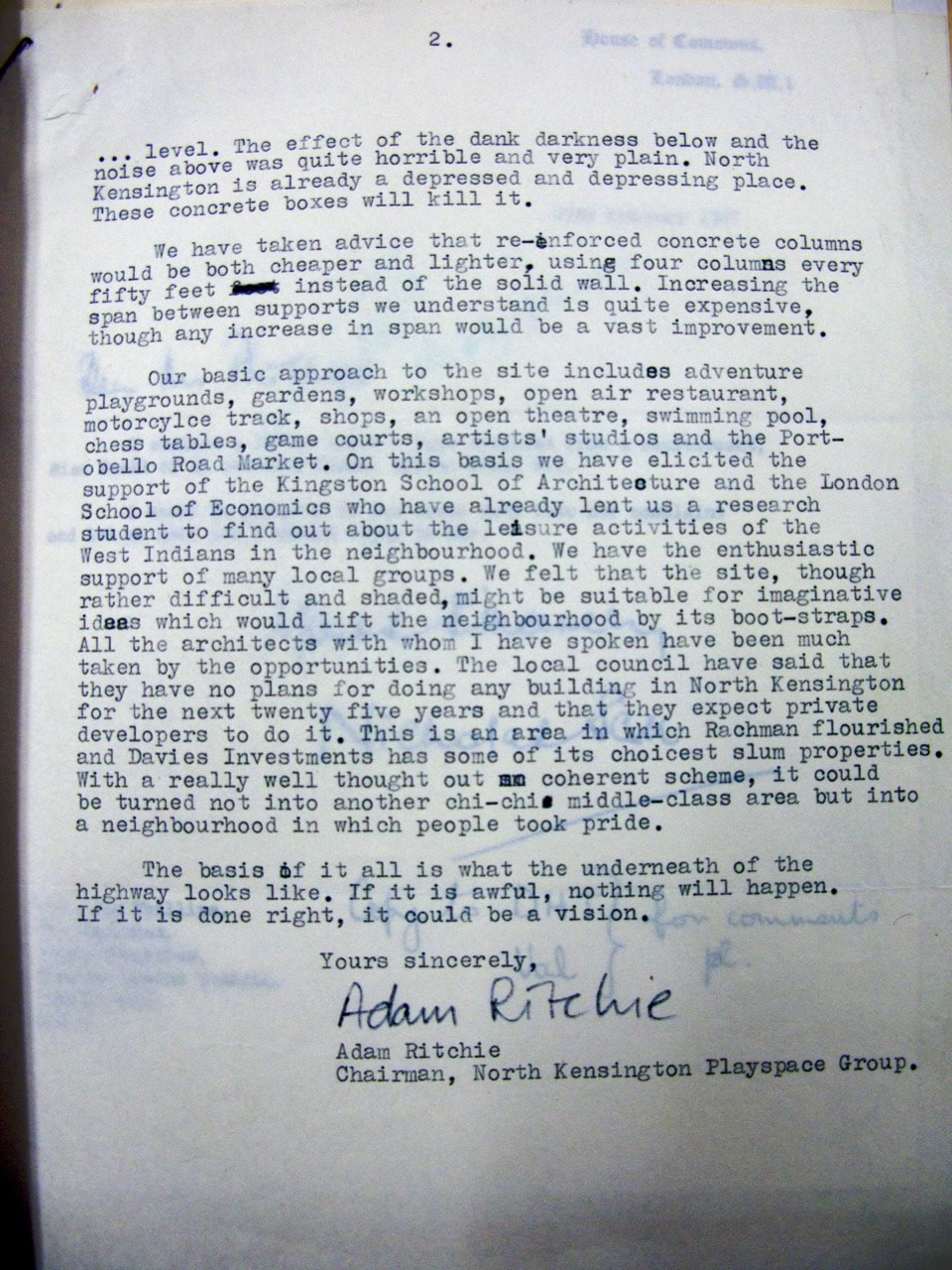

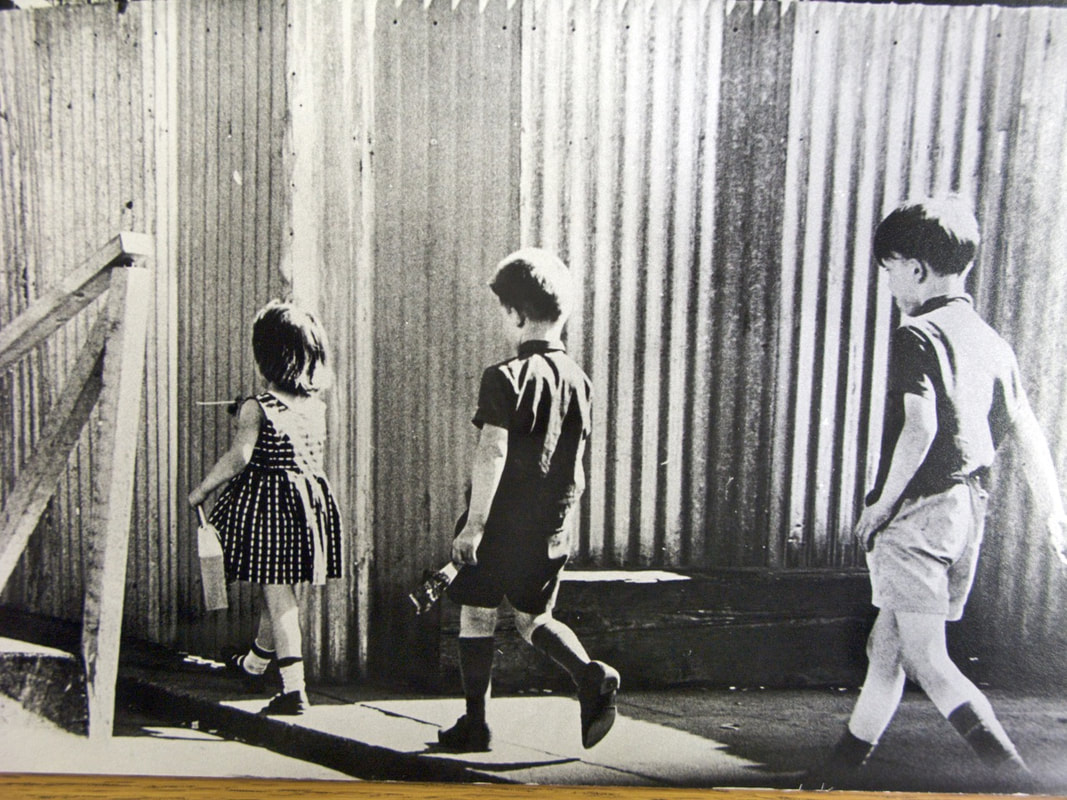

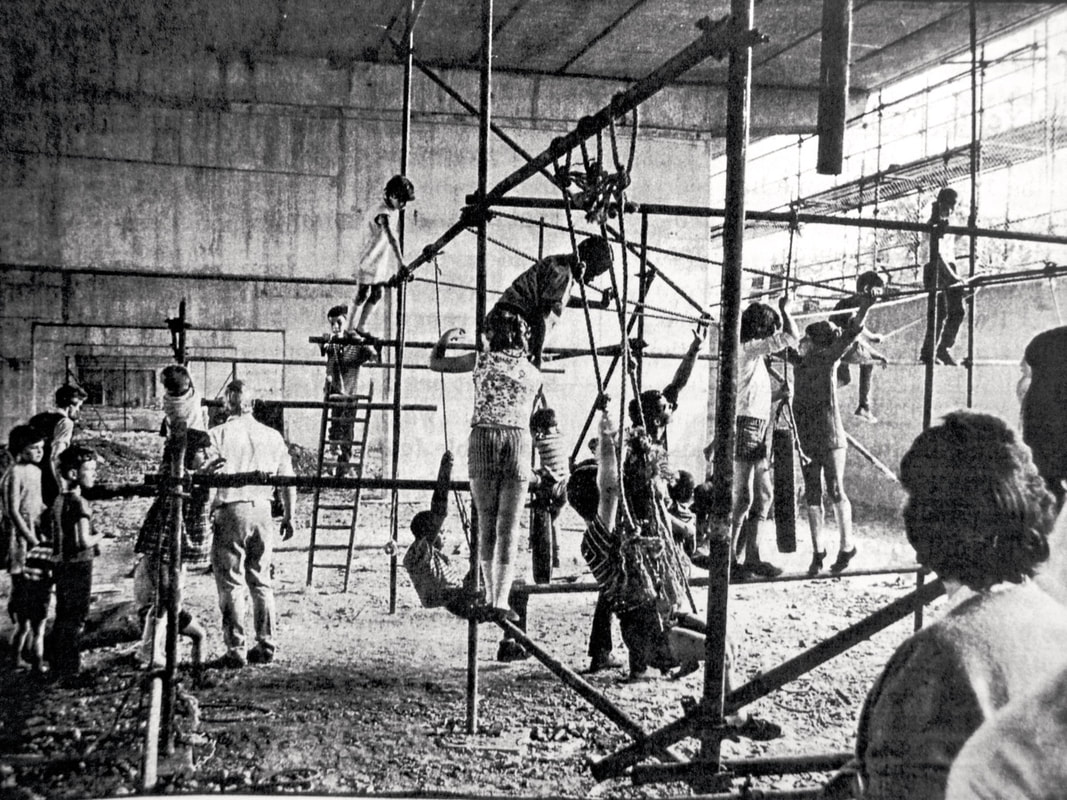

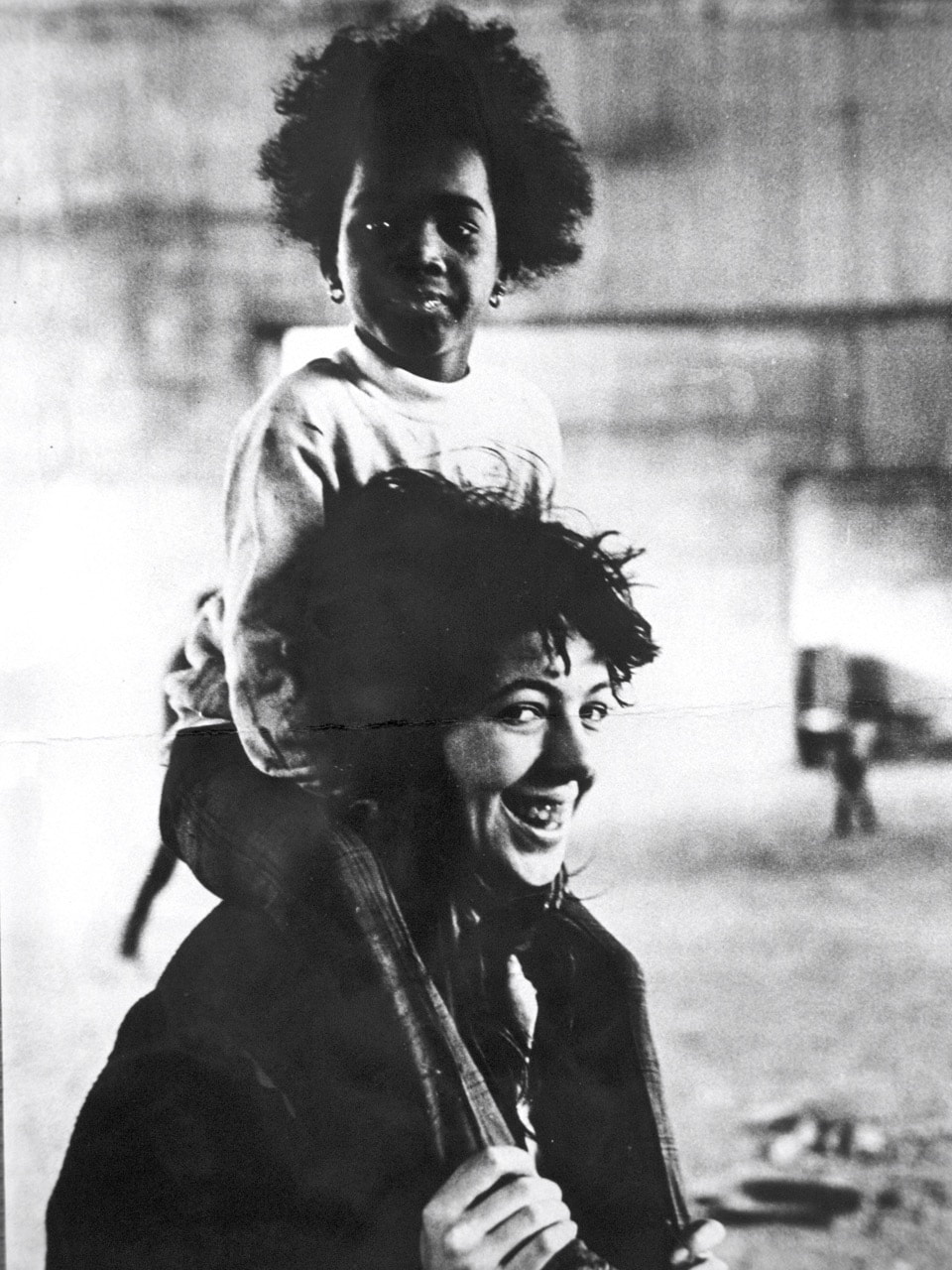

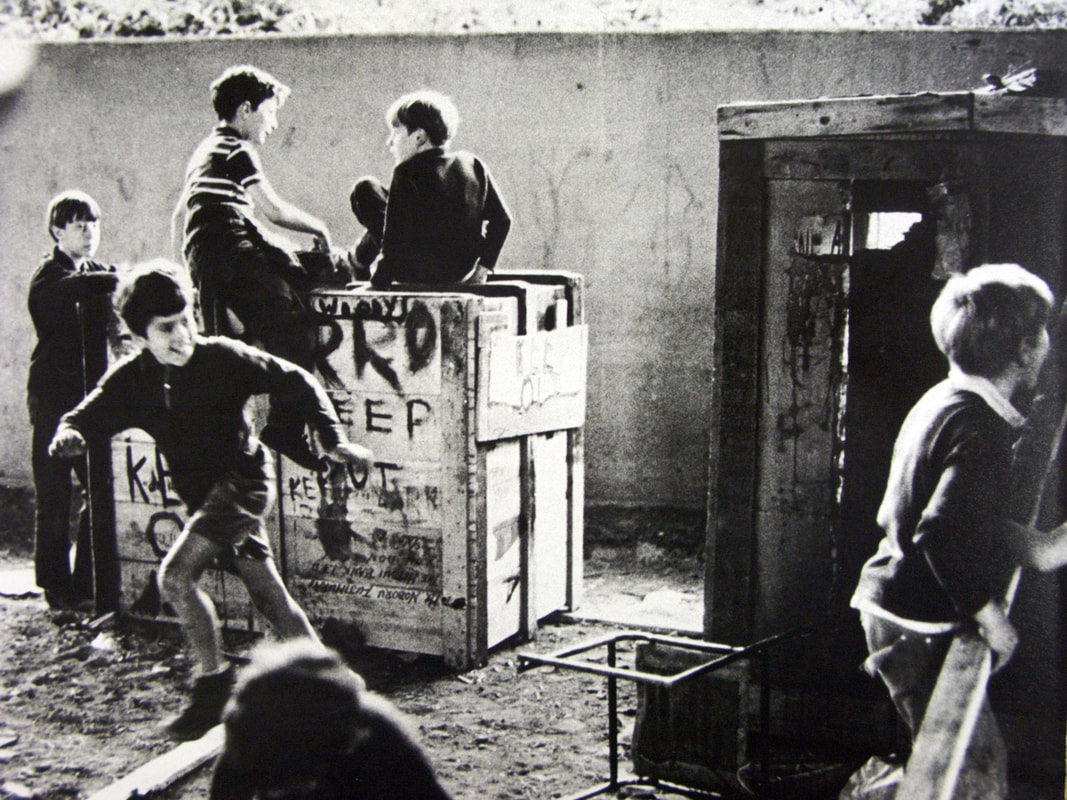

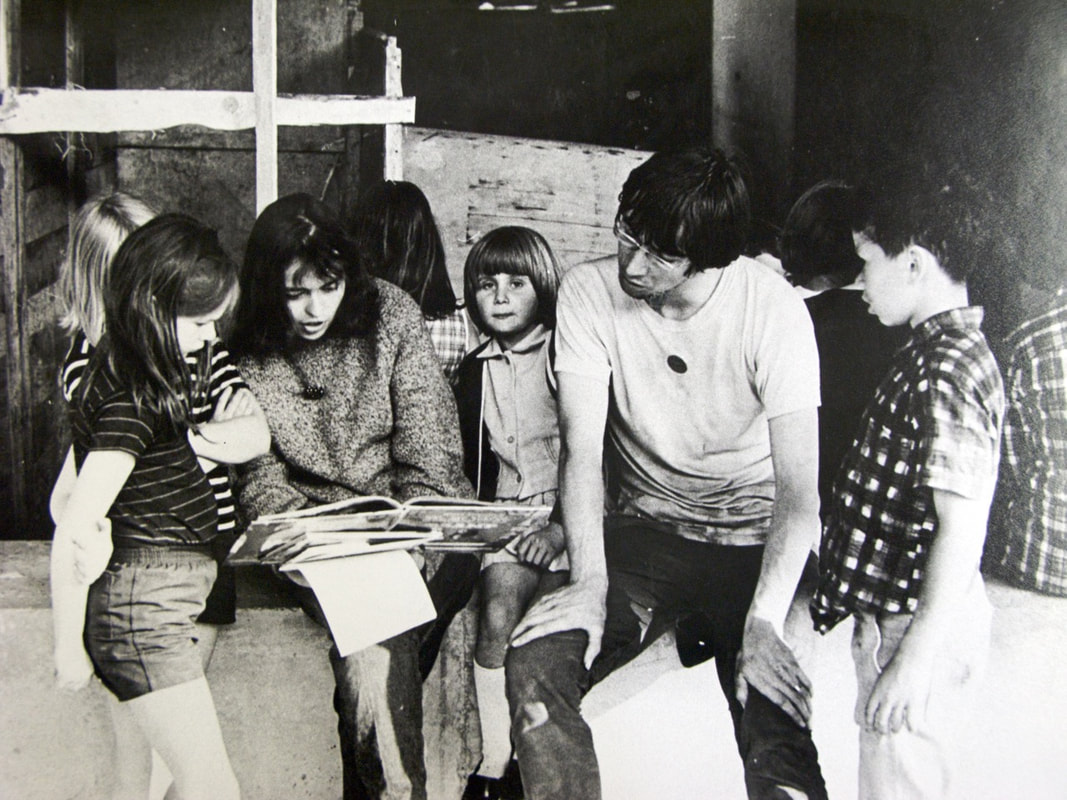

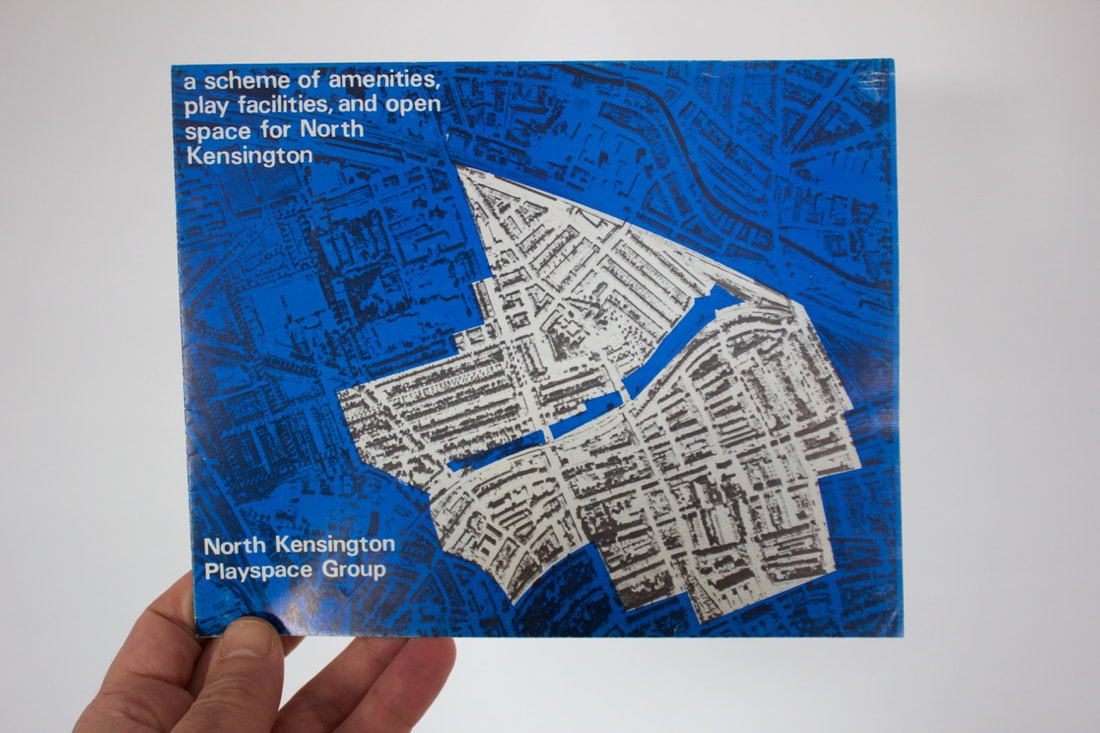

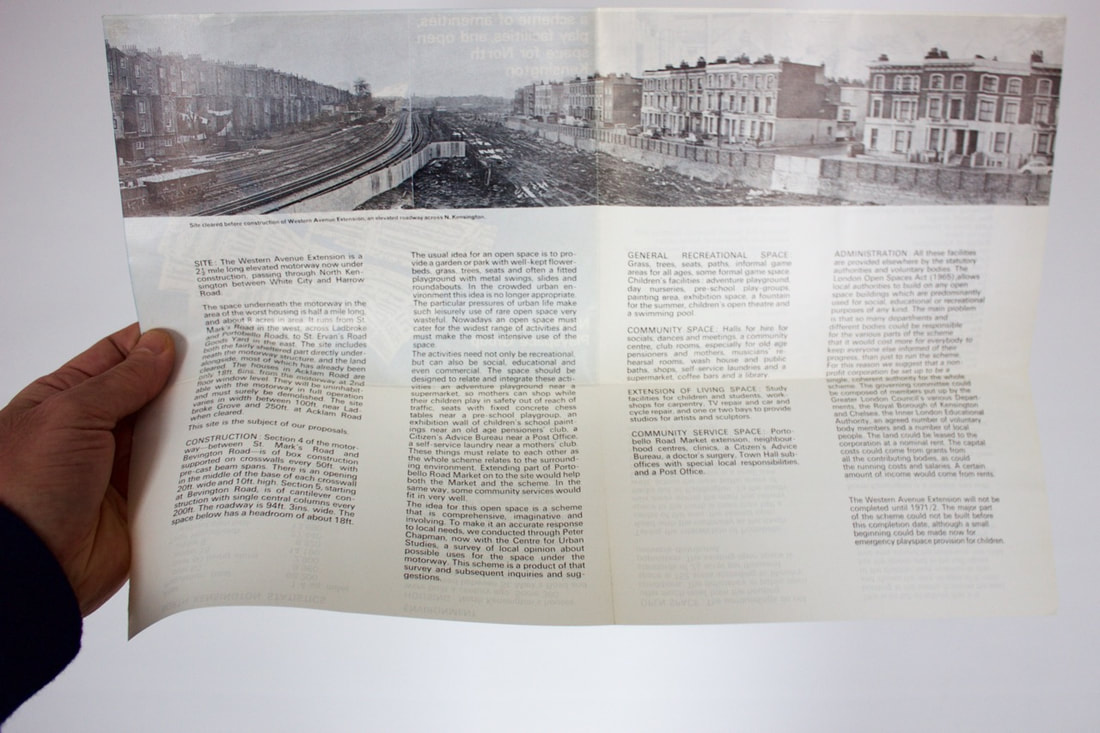

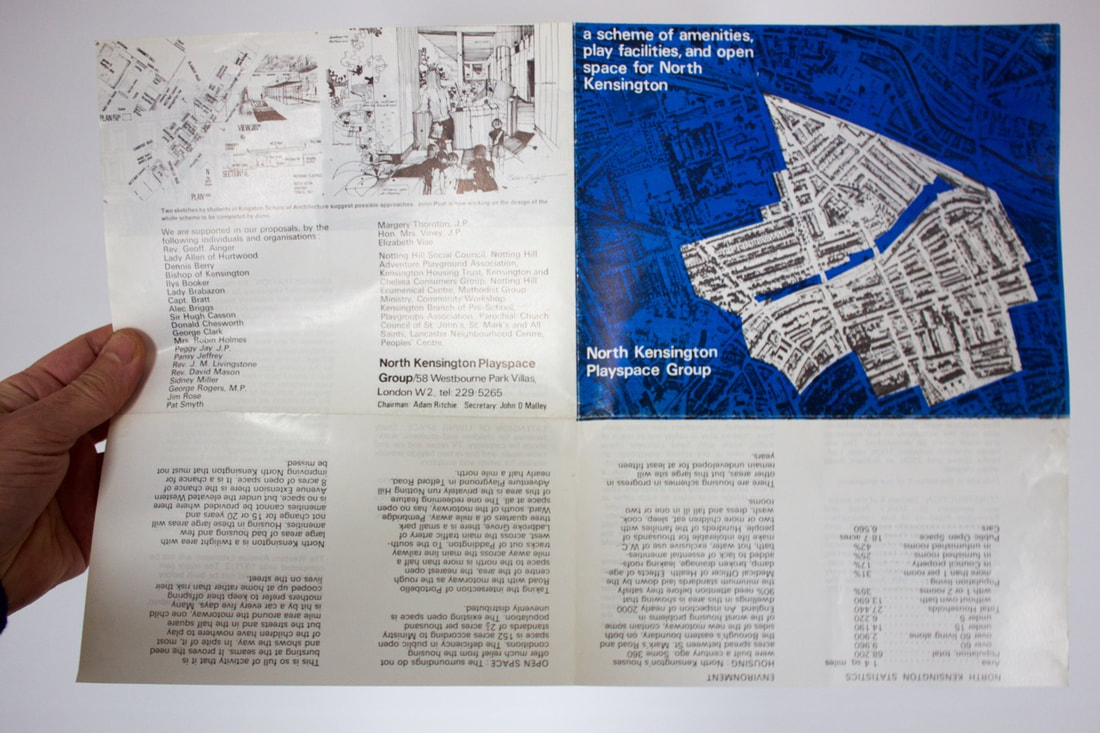

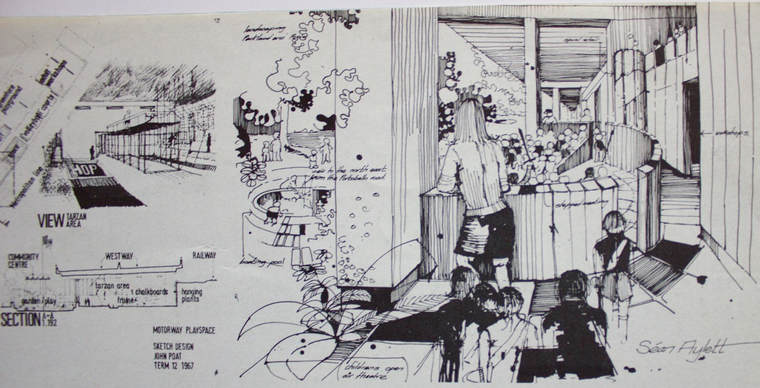

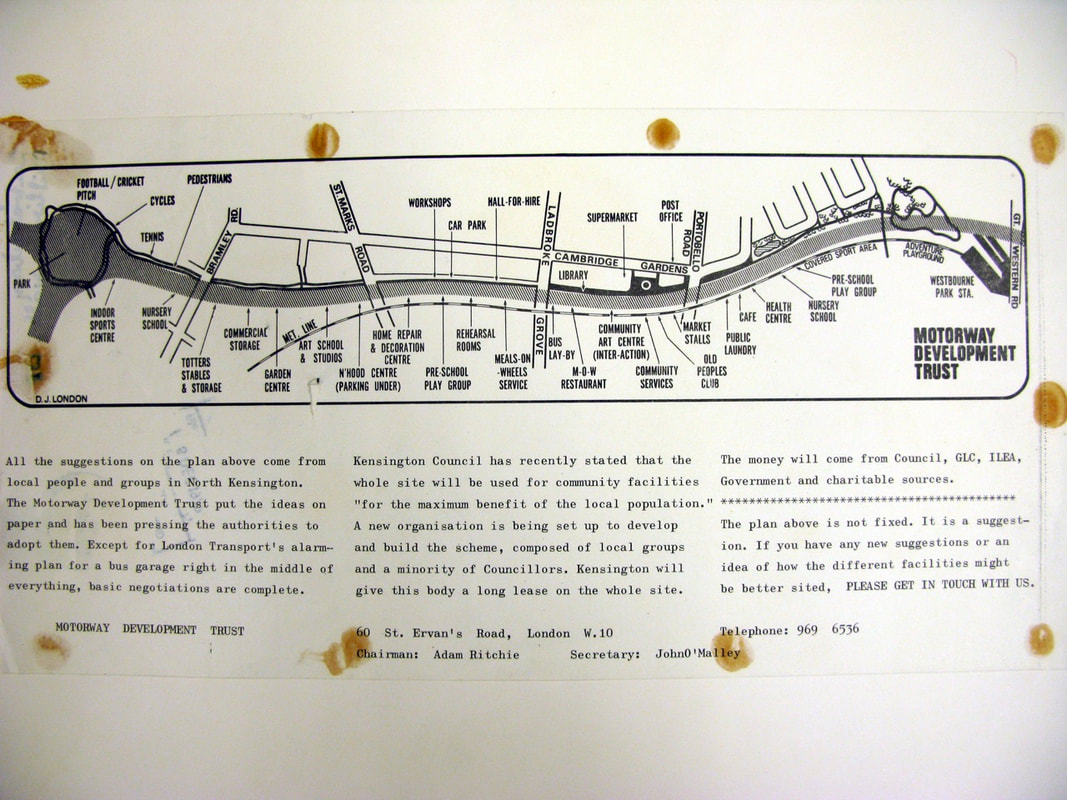

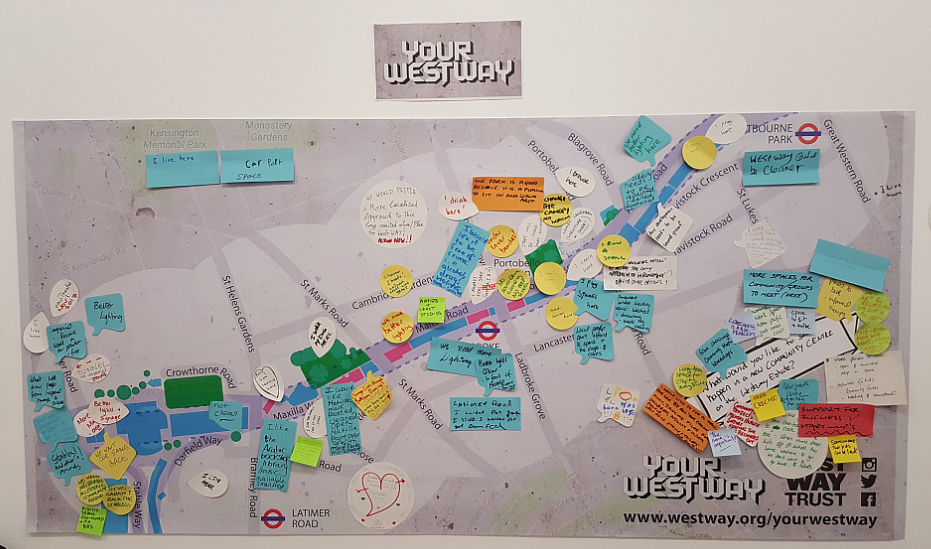

In 2010, when undertaking research for the film and art project, Flood Light, about the inter-related history of the Grand Union Canal and Westway (A40), I first came across the photography of Adam Ritchie. When I opened up that archive box and out popped these evocative black and white prints of children in a raw concrete space, I vividly recalled the 1970s and my own childhood. I was the first person in decades to contact Adam about these photographs and in the process discovered he was one of the founding figures of the Westway Development Trust; the unique 23 acres of land under the Westway flyover that was fought over and gifted for the benefit of local people. In 2015, I had the pleasure of interviewing Adam. He reflected on his father's legacy, the lows of education, the highs of the swinging 60's, community activism and on his fragile, but important photographic collection. It is timely to revisit the social conflict of the 1960s in North Kensington after the tragic Grenfell Tower fire. From a ruined landscape of houses demolished for the making of the Westway, residents were able to organise themselves and guide the woefully out-of-touch local authority into the making of community spaces and facilities. I’m sort of a middle class person, though my great-great-grandfather was born a bastard. My father was a journalist and broadcaster with the BBC. During the war, he invented the V for Victory Campaign. It was a big letter V that was chalked up all over the walls throughout occupied Europe by the people telling the Nazis that they would not win. This was a formidable psychological warfare campaign. He was very interested in the importance of the BBC being about truth. It couldn’t be like Nazi propaganda where they told lies and people were shot for listening to the BBC European broadcasts. I think I inherited the idea of the importance of truth and honesty from my father. I went to a public school which I hated as I was beaten every day for being the only socialist. The first day they asked you which way do your parents vote. I said they voted labour. I got hit. It was like that for the next few years. My father had a stroke and then we had no money at all for a long time. I got a scholarship to the French Lycée in South Kensington in the 1950s. Then I got another one to study at an American university in Massachusetts. I studied economics to start with because I wanted to work for the European Union. I thought that was the future for the UK. But the economics professor was so right wing, he took me aside one day and said, I don’t care what you do, I’m not going to let you pass anything in my department and I want you out of the college. This was because at his lectures, he said, if the workers could just observe the law of supply and demand and accept lower wages, then everything would be wonderful. But what about the workers, I asked? In the end, he got more upset because all the other students started to think ‘why should you just assume it’s okay for people to be poverty stricken’. I eventually changed to study English or American literature and I got on beautifully with that. The only non-fraternity place to live on campus was called Independence Hall. We each had separate rooms and there were a lot of women visitors. But one day the Dean said that for reasons of fire safety regulation we all had to leave our single bedsits so two people would share one bedroom and one study room. We all thought this was crazy, so I went to see the Fire Chief in the town. He said there was no regulation like that and didn’t know what I was talking about. But by the afternoon he had heard. He changed his tune because it was a one horse town; the college owned the town. About 2/3 of the students in Independence Hall upped and left the college. It was pretty shocking because a lot of them were in their last year. I left and went to Boston and tried to enroll in Harvard but that was impossible. In the end, I came back to England. I was very depressed. The whole experience was quite nasty. I worked at Better Books, in Charing Cross Road. I met up again with a friend called Nicole Lepsky who I last saw doing A and S Levels at the Lycée Francais in London. She asked me to come to a party near Oxford. I said, yeah. She was going out with a guy called John 'Hoppy' Hopkins. I met him and we got on very well. He was getting a flat at 105 Westbourne Terrace and it had lots of rooms. There were about 5 or 6 of us there including me. We smoked dope every night, listened to very modern jazz and someone used to read aloud, things like Samuel Beckett’s Murphy and At Swim-Two-Birds, by Flann O’Brien. We were always laughing our heads off. I always wanted to go back to America to see it properly. To get a Green Card in 1962 you had to have £400. I had £200 in the bank. I got a letter from my bank manager saying I had £200 in the bank. And then twenty minutes later I took all the money out. I went straight to the American Embassy, saying I’ve got £200 in cash here plus proof of another £200 from the bank letter. £200 plus £200 makes £400, doesn't it! And they gave me a Green Card. In America, I got a job as an economist at a place called Business International Corporation. I was hired to help give economic advice to the 100 top American companies wanting to operate in Europe. I got a loft and redid it completely. It had been a leather factory run by an alcoholic and his policeman brother. They made suitcase luggage straps, that’s all they did, nothing else. This loft was huge. I got on very well with the landlord who looked like a bowery bum. For some reason he got many of his clothes from his tenants; they threw them away and he would wear them. I don’t know why! His name was Seymour Finkelstein and he was a very pleasant man. He lent me all the tools and materials to do up this loft. I took off all the plaster from one wall, so it was a plain brick wall. I put in a bathroom and kitchen and built a huge platform to sleep on. I met Carola two weeks before I left for America. She was a typographic designer. I said, why don’t you come over with me! Two months later she left England and moved in with me into the loft. She got a job at Columbia University Press and did the typographic layout of their Encyclopaedia. In the end we were all evicted from the building. I think Seymour didn’t pay bribes to the fire department as it was illegal to have too many ‘artists in residence.’ You could have a license saying AIR2 meaning there were artists on 2 floors of the loft building. Seymour had 4 floors of artists and he wouldn’t pay the bribes, so they closed him down. Put padlocks on our front door and told us you’ve got to be out in 2 days. I found another place to live. One day while I was walking along a street, I saw a huge rat walking on the other side. It was walking quite nonchalantly, not paying much attention to anything. I thought, I’d really like a picture of this. I had a friend called Larry Fink who was a photographer. He had a darkroom just around the corner and I’d been talking to him about the images in New York I wanted to photograph. He said, why don’t you get a camera? I had recently just come back to England where Carola and I got married and I had about £150 from wedding money. I went out with Larry on a Friday evening to a big discount store and bought a good 35mm single lens reflex camera. On the Saturday I took lots of pictures and spent the whole of Sunday printing them in Larry’s darkroom. On Monday morning I was back in my office, with 15 good looking photos on my wall and the whole place, about 40 people working there, came by and said, 'Wow! These are really nice pictures.' The guy who ran the place asked me to photograph a Business International conference in Washington DC. I went down and took the photos and they got more orders for copies of the photographs than they’ve ever had using professional photographers. The head of the company at Business International, Bill Person, said, you ought to be doing photography and not economics. I said, photography is fine for a bit of pleasure on the side, but what’s serious is economics. He thought about it for a bit. He then sent me on a four day course to a company who test people to see what they were good at. It turned out I could be good as a lawyer, a journalist, a teacher. Nothing to do with photography. Bill said, “You should be a photographer. I’m going to fire you. You’ve got 3 months on full pay and you’re not allowed to come into the office except to show us photographs.” So I got sacked in this beautiful way. Only in America! He said something like it had happened to him and the change had been an important moment in his life. I went to the magazines and they all said, we don’t give commissions to people who have been a photographer for 2 months. I’d already saved up for a holiday trip to England with Carola and so I thought about what would interest Americans about England. This was 1963-64 and I noticed there were all these people in London who had important jobs and were around 22 years old. They were graphic designers, musicians, journalists. The fashion editor of the Observer was Georgina Howell, who was 23 years old. The fashion editor of The Herald Tribune in New York was 67. She was writing about young people and it felt weird. There were lots of people past pension age in New York running things. It was a cultural thing. In London it was all youth, youth, youth. I went to Glamour, a Conde Nast magazine, and said, I’m going to London in 2-3 weeks and I want to photograph these people, They are all under 25 and they’ve done really amazing things. Again, they said we don’t give commissions, but we will look at the photos when you come back. We might be able to publish a page. I came back and they published 6 pages and they gave me work every month after that. That was an amazing start. At the time, I made a film with a friend, Yvette Nachmias, called "Room 1301.” It was about the office environment in New York when she was trying to go down one floor from the 27th to the 26th floor. The door locked behind her and she couldn’t get out on any floor at all. She walked down 27 flights to the basement and out onto the street. There were alarm bells going and 6 fire engines around the front thinking there was a fire. She went back to her desk and didn’t say a word. It was quite a nice little film shot on 16mm. Before I came back to England in 1966 for the birth of our son, several interesting and important things happened to me in New York. I lived just around the corner from Tompkins Square on Lower East Side. This was a completely flat square with lots of pathways with concrete fencing on each side and some tiny patches of grass also surrounded by concrete fencing so you couldn’t get onto the grass. Mayor Wagner had a brother who was a concrete manufacturer. The city covered everything in concrete. People used to come to Tompkins square and had to lift their dogs over this 5 foot high concrete fence around every patch of grass. One day, the mayor started to build a concrete stage with a roof on it. There were diggers and this huge mound of earth next to where they were going to build this thing. They laid the foundations. The kids took over this hill of earth and they ran up and down it until it was smooth and wonderfully evenly shaped and not muddy anymore. It was the first thing that was alive in this whole square. There also was a change of government with Mayor Lindsay. His new parks commissioner, was Thomas Hoving, the son of people that started Tiffany's. The contractors said that they were going to come and remove the earth. The mothers realised that the earth was very important for the kids. Someone phoned up Thomas Hoving and said you’ve got to come here because there is going to be trouble with the contractors ruining the last bit of our square. The mothers formed a circle and hundreds of kids were all on the mound and the contractors were ready with their machines. Thomas Hoving arrived in a big limousine with police motorcycle escorts. He talked to the contractors and he came and talked to the mums. Then he walked up the hill and down again. Talked to everybody once more and then said: I think it should stay. They called it Hoving’s Hill after this. I thought this was very exciting. It was political, very direct and everything was right in front of you. Also the fact of the mothers taking ownership of the space was very interesting. There was one other thing in New York that was also an inspiration to me. Hoving fenced off a small bit of Central Park and set up poles every 3 feet and hung canvas from one end of the poles to the other. There was a 3 foot by 2 foot high rectangle of canvas attached to them. Brushes and paints were supplied. And it was called Painting Day. People came and painted all day on both sides of the canvas. I think they burnt the whole thing when it was over. Then the picket fence was taken down. I thought that was fantastic and it was all done in one day. I came back to London with these two things buzzing in my brain. I went to see Hoppy and he’d set up the London Free School in North Kensington. They met and discussed things, had classes in whatever you wanted to know about. There were philosophers and writers and artists. They probably used the All Saints Church Hall for quite a lot of stuff. I think one of the things they organised was the first Carnival in London. It was not anything remotely like what we have now in Notting Hill. Rhaune Laslett and Hoppy started it. They just thought, let’s have a festival, This was about 1966. It wasn’t really organised and I think it was gently raining. I saw about 20 or 30 people walking past where I lived. They were singing and dancing and having a nice time. But they also got permission for an adventure playground where the houses had been demolished for the building of the Westway motorway. They put up a rather beautiful painted sign saying London Free School Adventure Playground - Come and Play. I went there and saw it. It was all demolition rubble about 5 or 6 feet below the pavement and there was a brick wall all the way around to stop people falling into the rubble. And there was a plank against the wall. If you were athletic enough you could maybe slither down this plank. The kids did it without any problem. I never saw an adult there except a bit later. The kids built things out of the rubble from some of the 600 or so demolished houses. This was Acklam Road between St Ervans and Wornington Road. So quite a large site. And there were all these wonderful things being built there by the kids out of the rubble. I thought they need a bit of material help. I bought two hammers, a saw and huge bag of nails and hid them under the rubble. I came back a few days later to see there was a new building. It was really bigger than what was there before because of the nails and tools. I was very excited about that and told friends. We all went to see this building a few days later. But the thing I had described in such detail wasn’t there. Instead there were 3 other buildings even bigger and better. I just thought that was fantastic how kids and people could just do things. All you needed to do was just twist it a little bit. God knows, we need a little help at times! There is also the innate impulse to do things and to have the opportunity. There was all this rubble, What do you do with it? You build buildings, that’s what you do with it! I went to a meeting of the London Free School at the All Saints Church Hall in Powis Square when they said that this is the last meeting. I said I’m really interested in doing something with the adventure playgrounds idea because they are going to build the motorway and this has got to be thought about. What are we going to do underneath the motorway? There were 5 or 6 people who joined me including John O’Malley. We formed the North Kensington Play Space Committee and met at my place for 3 or 4 years after that planning, talking to people and writing letters; I must have written 1000 letters. I was working nearly full time on it for 2-3 years as well as teaching photography at Central School of Art. Adam Ritchie's photographic prints of organised play schemes under the Westway, 1968-69 Kindly reproduced by Adam Ritchie and RBKC Local Studies and Archives As the motorway was being built, we asked for a meeting with the Greater London Council. They agreed to this and phoned to ask were we bringing anyone else. You could hear their jaw dropping as we said, yes, we’re bringing Sir Hugh Casson who was an architect and planning consultant to the Queen and Ottawa and 17 other cities. He was a big deal. And we're bringing the secretary of one of the largest charities in London. We are bringing Peggy Jay who was the parks committee head of the previous local government. She knew everything about how things were done. And we had Ilys Booker, a sociologist, with an international reputation, who was working in Notting Dale and she supported us. It was an extraordinary list of people. When we came to the meeting there were maybe 60 people in the room. They had all their officers and secretaries and committee people. We came with our lot who all gave fabulous speeches. We also had a half page article in the Times and a leader in the Guardian all in favour of our plan. They agreed to further meetings. Later they said we couldn’t have community facilities under the Westway, because they had planning permission to build a car park under the whole of the motorway. They were going to build a 22 foot high concrete wall shutting off the underneath of the motorway for the car park. It would just become this awful space. One of the imagined reasons for the motorway was to reduce local traffic and if you got a huge 8 acre car park underneath the bloody thing, where are the cars going to come from? They are going to come off the motorway and park there. Everything was so badly thought out. We hired a barrister to contest this. He wrote a letter to the Transport Minster asking whether they had planning permission. Just by chance we knew Donald Chesworth, who had been on the Planning Committee 15 years before at the London County Council. He said, I don’t remember agreeing to a car park. I phoned up the Town Clerk of the GLC and said could we possibly have a copy of the minutes of that meeting at which the planning permission was granted. There was a gulp at his end. The next day the 22ft concrete screen slabs that they bought or had commissioned, thousands of them, made to wall off the whole of the underneath of the motorway, was stopped. I don’t know at what cost. They had to abandon the whole thing. But we were a bit nervous about chasing them legally because we were trying to get their support for our scheme. It was swept under the carpet. But they had told the Transport Minister that they had planning permission and this was a lie. If anyone thinks that officials are telling the truth, they may not be and you need to double and triple check. I forgot to mention that we had someone from Kingston University Architectural Department who designed a pamphlet for us. This had an air map of North Kensington with the motorway on it and our plans for the spaces underneath. We also got sponsored by the British Road Federation because we were the only people suggesting a possible social use of a motorway; but I was really against roads impinging on everything without any obvious advantages. BRF gave us a stand at the motor show which would have cost us thousands of pounds and they paid for all our materials. We produced this 15 or 18 foot long map of the motorway cutting across North Kensington showing its beginning and end. At public meetings we stuck this map on a huge series of boards and talked about the whole thing and said - imagine you’re a bird looking down on this, this is what it looks like. So people who didn’t read maps could get this scene of what they were proposing to do. And we gave out bits of paper and loads of magic markers and they could write down what facilities they wanted and where it should go under the motorway. It was real site-specific thinking. We were clear that we couldn’t put our own ideas forward. So all of the ideas were from peoples’ suggestions at public meetings and by talking to people. Almost everything suggested was practical and sensible. I was knocked out by this. We also went to see a big London charity and discussed it several times with them, A wonderful man ran it called Tony Woods. He was excited about what we were talking about. We said could you put aside money for when it is needed. And he said, I can’t exactly remember the amount, but something like, I can put aside £20,000. It was serious money, He said he’ll put it forward for the next 3 years so that it will be available when needed. We worked with an insane confidence of thinking of things like that. If you are a little tiny group flaffing around on the outside of this circle, there was no reason why you’d think of things like that. But we did. I think our political thinking was pretty good. There was no possibility that I could have done any of this without John O’Malley. He was absolutely a rock. He and his wife lived and worked at the Community Workshop in St Ervans Road. They were community organisers. Jan worked on an area that I thought was more serious, housing. She did a huge amount of research and had a real strong framework of understanding what the problems were and how to solve them by helping people. Many commentators said that North Kensington had the worse housing in Britain. It really was overcrowded, with decrepit, often disgusting, bad housing There were 15-16 people living in a house with one toilet that was overflowing and with no heating. Rachman-type landlords who didn't give a shit about these people. Horrible! John and I organised play projects that were temporary schemes and hopefully would become permanent. So for example, we ran the Summer Play Project in 1967 that had 200 students from all over the country coming to help us. We got a disused school to house them. We got a grant to pay for a secretary and changed our name to the Motorway Development Trust because we spent all our time on the motorway scheme. We didn’t have false ideas of anything. This was quite important. We always knew that we couldn’t get what we wanted, which was for the community to have control over their own area. But we could do a hell of a lot better than just having a car park under the motorway. One of the principles behind the whole campaign was that we had to have fun while we were doing this. You can’t do any good if you are not enjoying yourself! The council agreed to setting up the North Kensington Amenity Trust that would run the spaces under the Westway. The council wanted to set it up with the Town Clerk as Secretary. This would have been a really poor organisation. We were quite good friends with the Charity Commission and suggested this wasn’t the proper way to set up a charity. It was a way of subsidising rates and so the council was put right on that and had to change the complexion of the organisation. We also had to have an independent chairman. The council chose an ex-ambassador and we then had middle of the road people. In my view, people who basically didn't want to rock the boat with the council. Establishment people. John and I weren’t allowed to be on the committee until we got the Charity Commission to insist on more openness and then got elected onto it. It was stultified for many years because of the lack of imagination of the council in dealing with it. They probably let us on in the end because they didn’t have any ideas and we had quite a lot. At all our meetings with Kensington Council we did the soft cop, hard cop thing. John would go in with his Arran sweater and he looked unshaven and radical. I would go in like a posh kid from Chelsea. They couldn’t believe the radical things I was saying and were then surprised that John didn’t bite their throats and had these practical things to say. But the Trust didn’t like it. In the end, I got a job building houses in Wales in 1973. I stayed on as an elected member on the Amenity Trust for a year or so and came to London for the meetings. We had started with the idea for an adventure playground at one end of Acklam Road. Then it became a mile-long strip up to White City. A lot has happened that seems a lot better than a giant car park and some has developed based on community amenities rather than just commercial. We always included in our plans some commercial space because it provides jobs and some income. We have seen gentrification increased beyond belief but there is not much you can do about that with so little community controlling their own space. Original vision for community spaces under the Westway, 1968 Westway Development Trust consultation on how to regenerate the spaces, 2017 Adam Ritchie with the Latymer Mapping Project, 2013 Postscript: Photography I used a photo lab over the years because I was never terribly interested in printing. They also had all my negatives, 10-12 years worth going back to my time in America. It was stored at a place called Sky Labs which was in Maddox Street to start with and then moved to various places. I hadn't spoken to them or been in touch for about 3 or 4 years because I was building houses in Wales. I popped in and asked for a picture from my negs. They said we don’t have your pictures. I walked out and thought that proves that I’m not a photographer anymore. It wasn’t a tragedy. I didn’t go back in and scream or shout. I wish the hell I had now! They closed up their old shop and as I had moved a few times, there was no way to get in touch with me. They probably put it all in the skip. It’s very sad because I had some nice pictures. I think the ones of the kids playing were the best ones I ever took. I’ve probably got 10 prints left altogether from thousands of pictures. My colour slides and contact sheets of Pink Floyd and Velvet Underground happened to be in a bag in a parking bay under Trellick Tower which I hired for storage. The bay was broken into and wrecked with paint poured over everything. But they didn’t take or destroy this one bag which had all my Pink Floyd and Velvet Underground photos. They have since been published in thousands of books, magazines and newspapers and exhibited at the Tate, Liverpool, the V&A and the Whitney Museum in New York. I only take a few snaps now. There was something so free about taking photos then, less self-consciousness. www.adam-ritchie-photography.co.uk An exceptional ceramic object was made recently at one of the workshops I'm running at Silchester Estate. Cerys Rose made a tower block to begin with and then added this onto a base structure. But it was what she did next that was truly remarkable and inspiring; she took a conceptual leap of faith that is advanced in one so young. Cerys playfully added on what appeared to be flying buttress supports. I then asked her to reflect on what she did: "My art piece is based on protecting. It is a peel, for example a banana peel. When it is peeled, it is not protected. When it is not peeled, it is protected." So much for flying buttresses! Cerys was on a more imaginative wavelength. At the time, I didn't want to ask her whether the banana protection of her building was in reference to Grenfell tower which looms large over all of us in the area. Cerys's friend, Sina Michael, another very talented artist, had made a more direct reference to this in her scale model ceramic work of the five high rise tower blocks that dominate the local skyline. As residents at Silchester Estate shape clay into objects real and imagined, sublime and surreal, my mind wanders back to two previous ceramics projects. One that I have blogged on and another that I have repressed from living memory, until now. Leo The Last is a 1969 film that I used as a meditative tool and to create art with residents of the estate in 2015. This wild and experimental film, tapping into the counter-culture of its era, has mythic qualities for our patch of North Kensington in London. It is a true Notting Barns film made on the plot of ground and in the soon to be demolished “slum” houses on Testerton Road before they were developed into Lancaster West estate and Grenfell tower. Leo is an aristocrat who has moved into his million pound white house that is cheek by jowl with the black painted properties of his down at heel Afro-Caribbean neighbours. Leo becomes radicalised, albeit in an idealistic fashion, after he discovers he is the slum landlord for the area. The film ends with a community riot that burns down his house. Leo is philosophical about not being able to change the world, but we can change our street. After screening the film on a 35mm print for the general public, a group of residents went to the V&A and created houses and other structures under the supervision of ceramic artist, Matthew Raw. I was then able to use these to re-create the road that you see in the film. This was displayed at the museum as part of my end of residency display of art. In a prophetic parallel, Cllr Rock Feilding-Mellen, had the opportunity to become Leo. Rock is not a film character, but a Tory Councillor of aristocratic origins, who moved into a posh property that was located across the road from Lancaster West estate. But there was no sense of him becoming radicalised by his neighbours or attempting a more modest community engagement here. His job as deputy leader of the council and head of regeneration was to mastermind the plans for the systematic regeneration (i.e. demolition and disruption) of Silchester Estate. This was at the same time he was directly responsible for the modernisation of Grenfell tower. You cannot watch Leo The Last now, without making these poignant connections. When I was inviting residents to make ceramic houses and reflect on social history and its relevance to the contemporary world, I had little idea what was about to happen in North Kensington; or even how that might radically change me. I feel my art engagement here was sympathetic to the local residents and their sense of place. However, if we go back a few years to 2012, another ceramic art project was artistically and socially less successful.