|

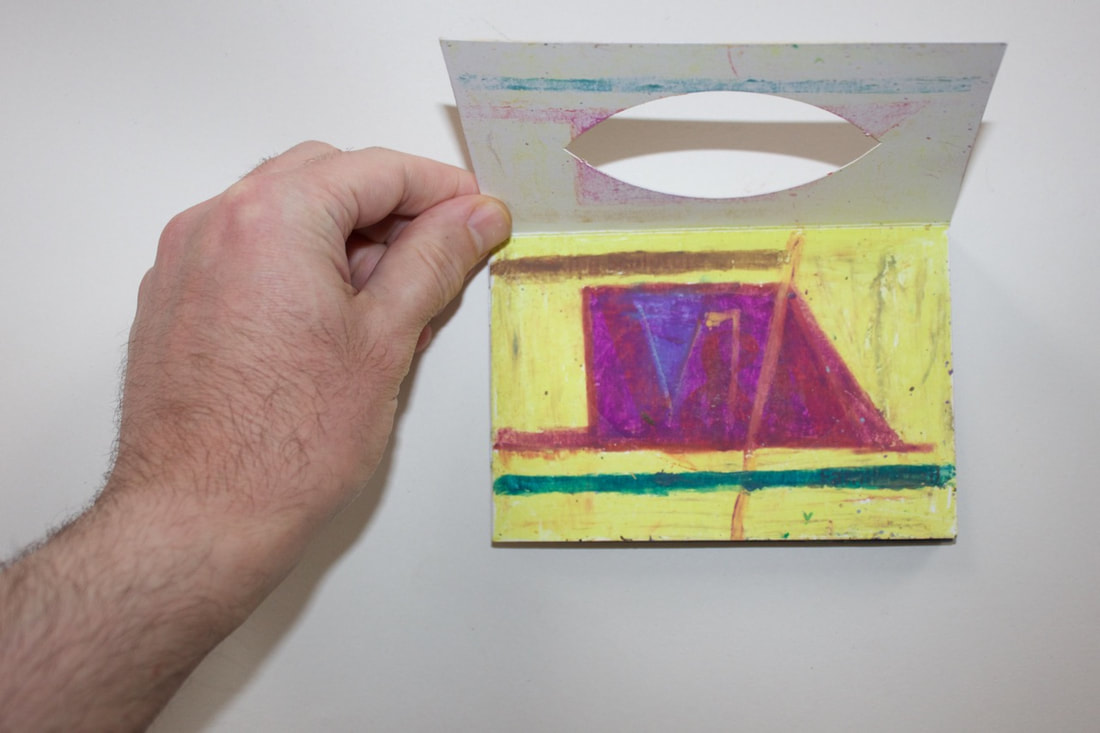

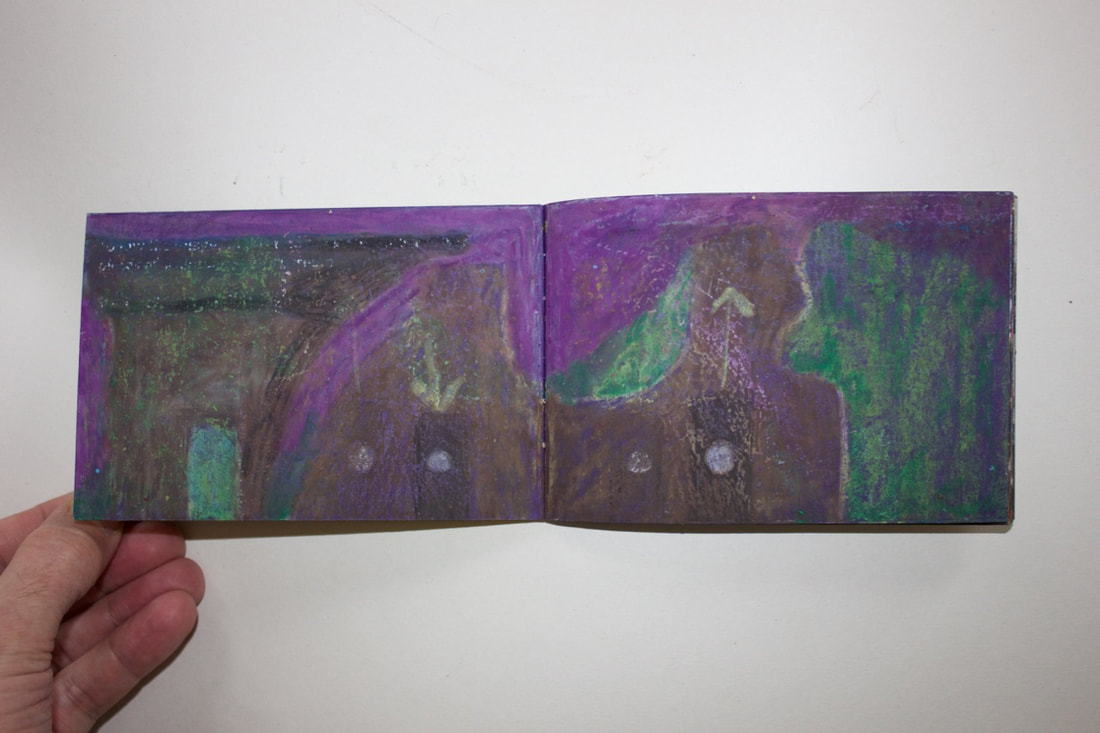

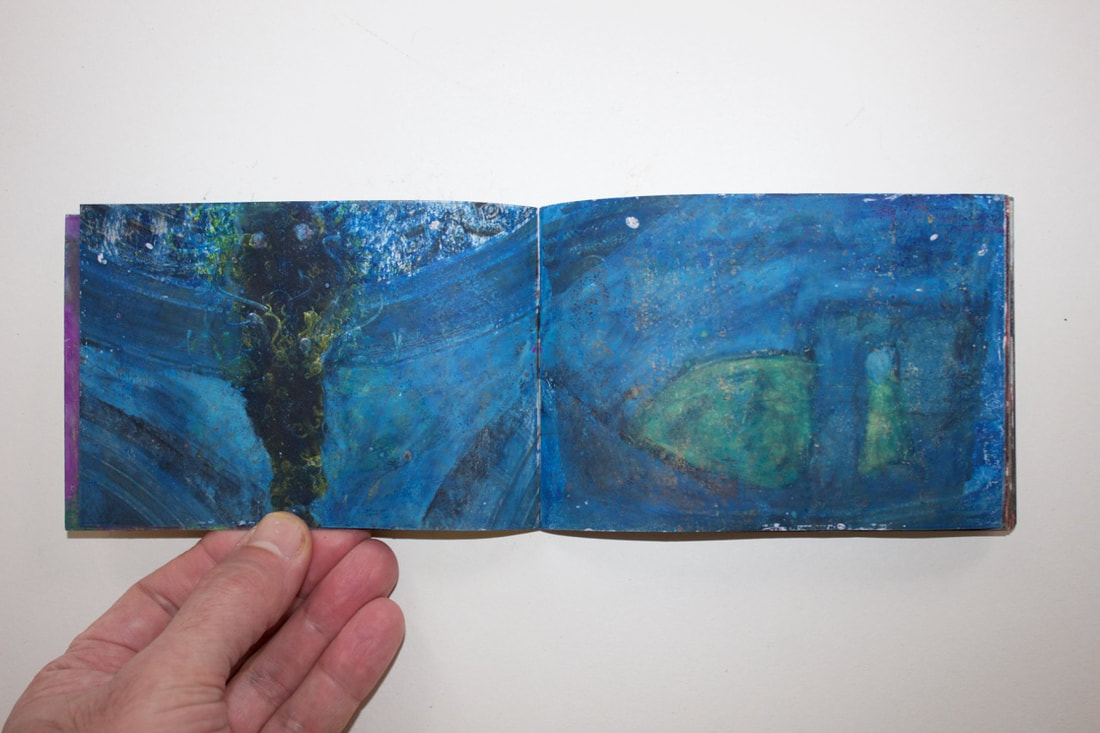

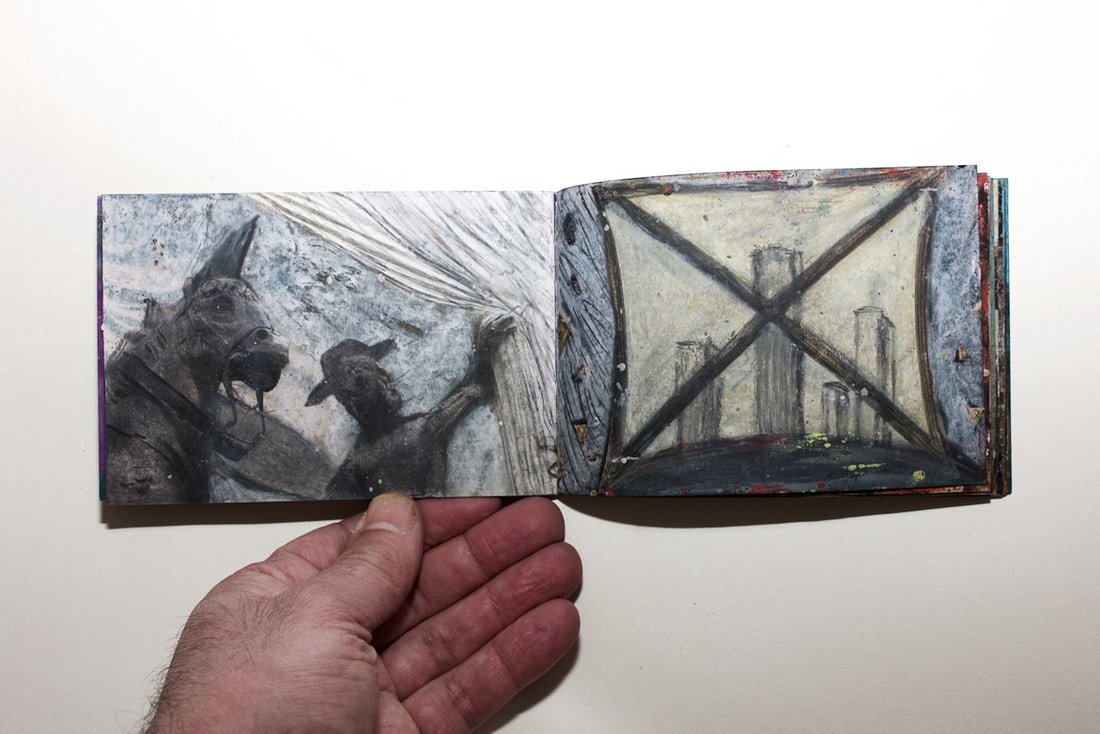

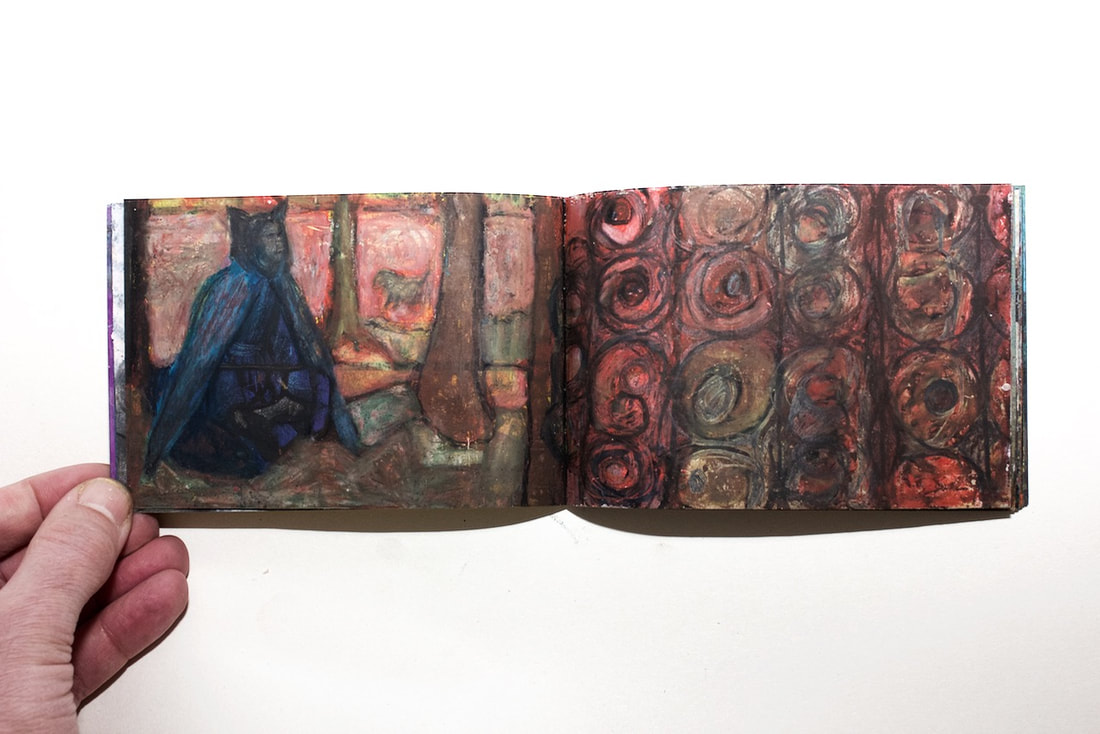

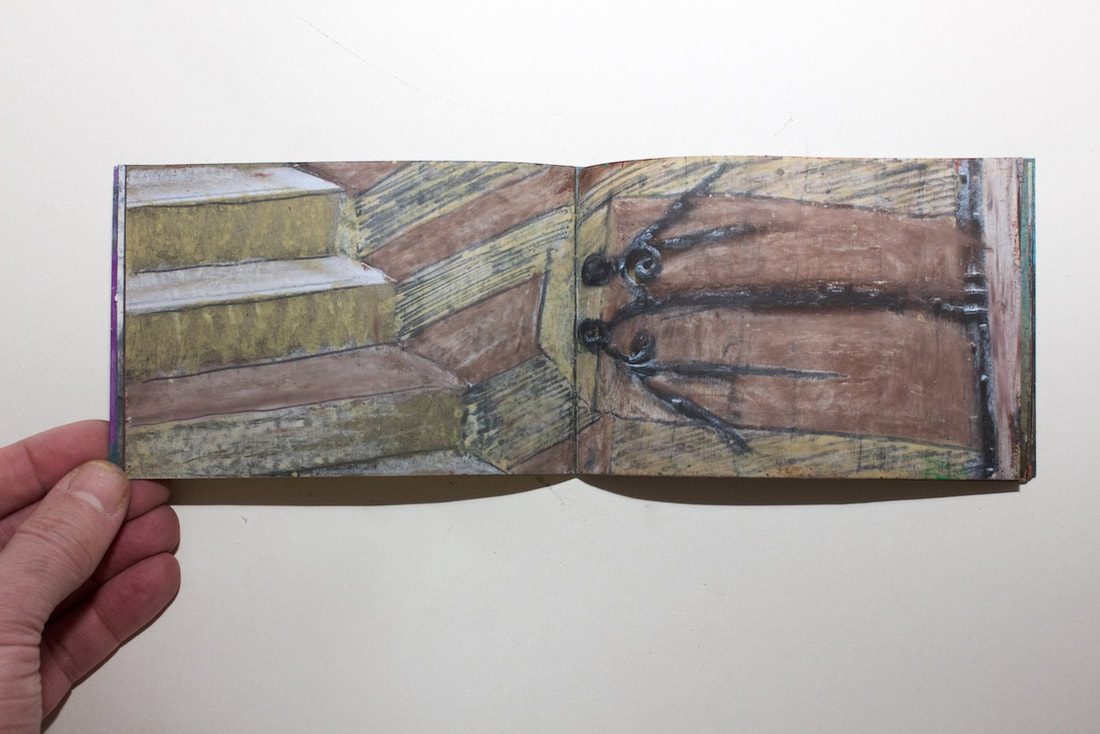

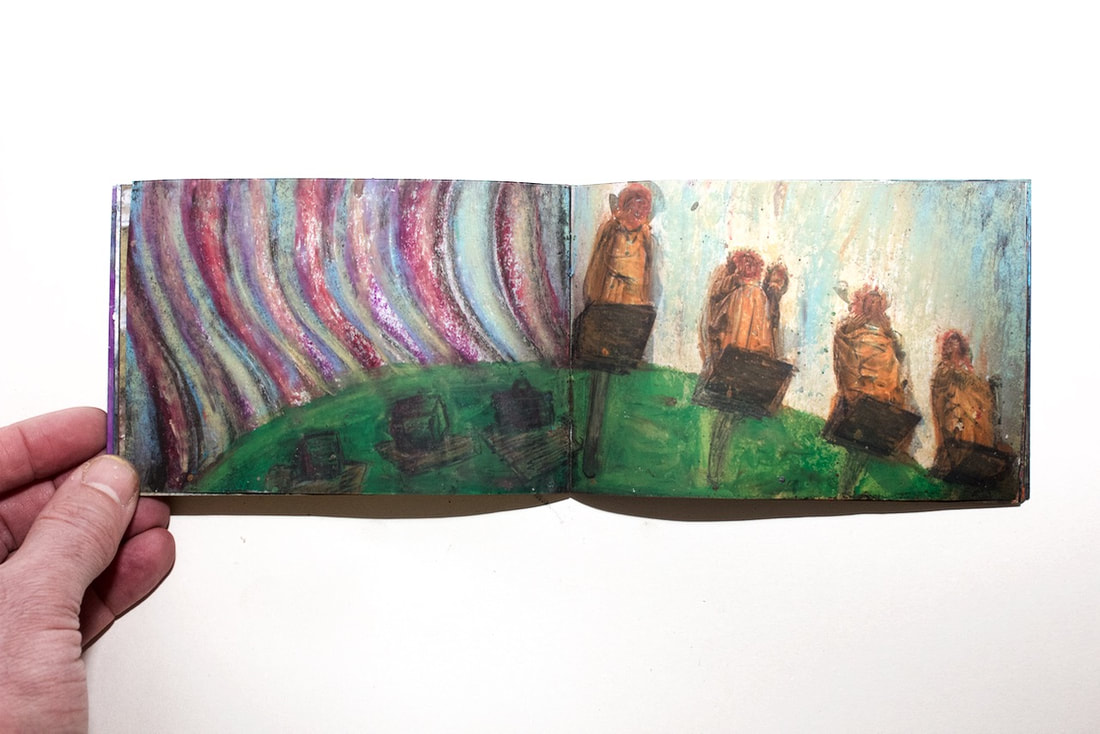

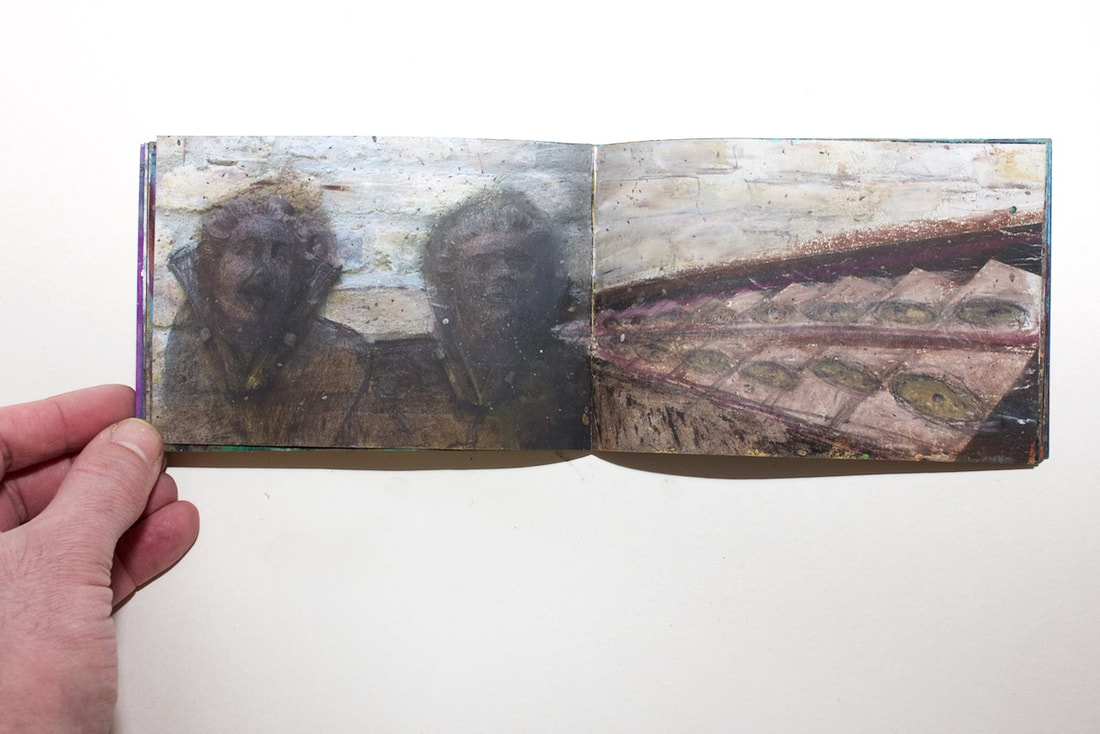

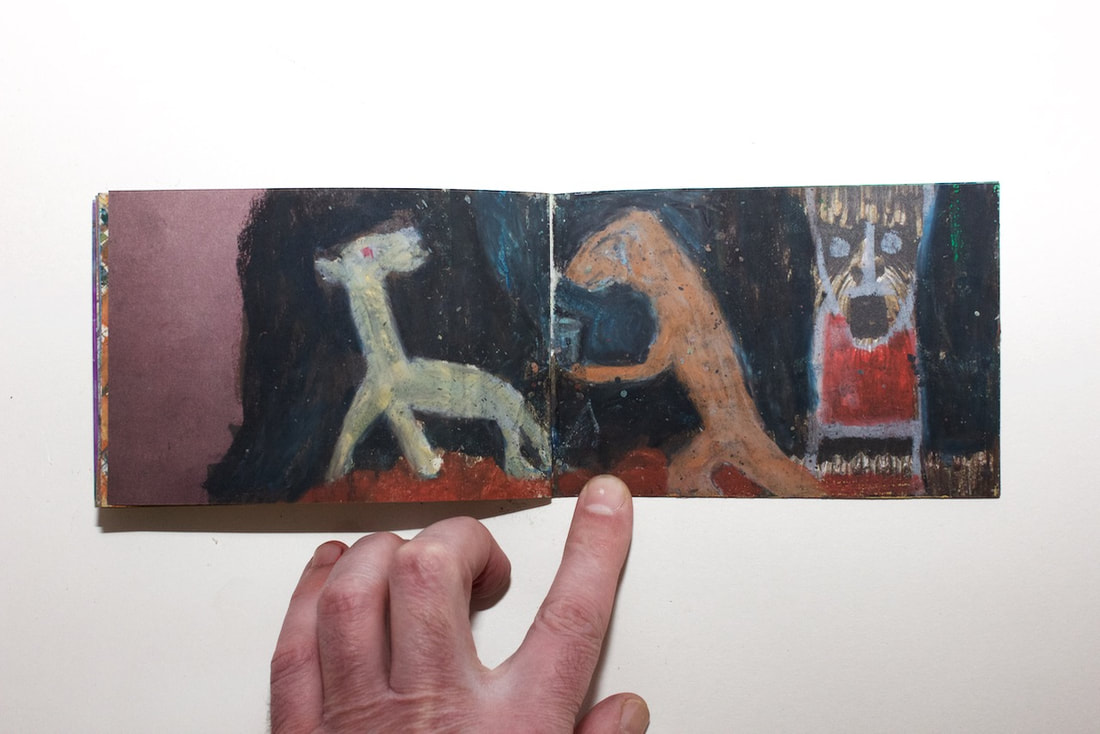

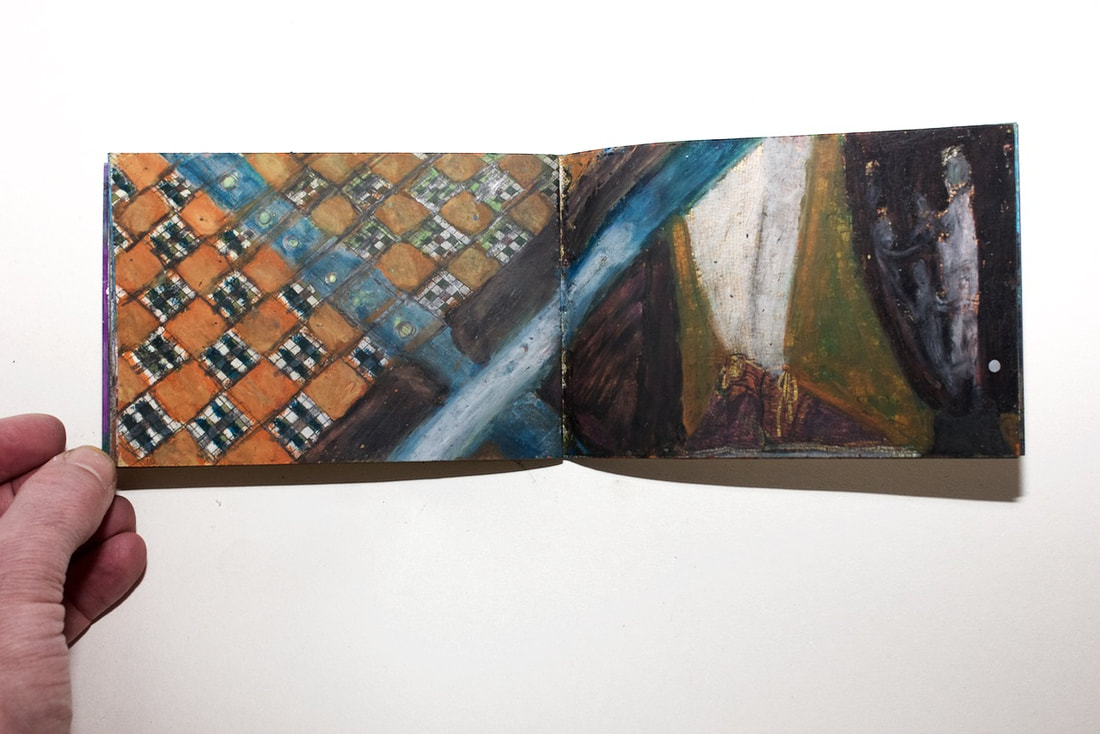

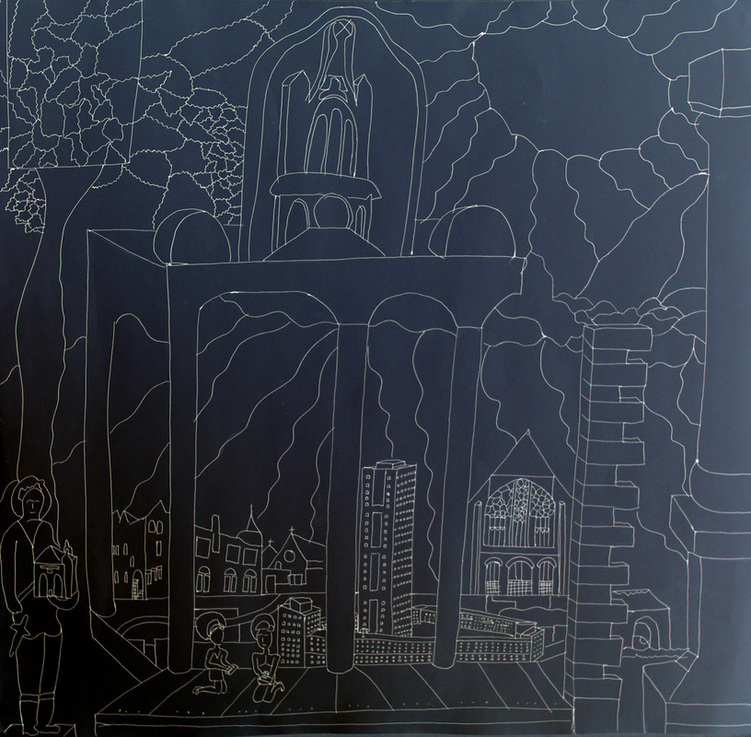

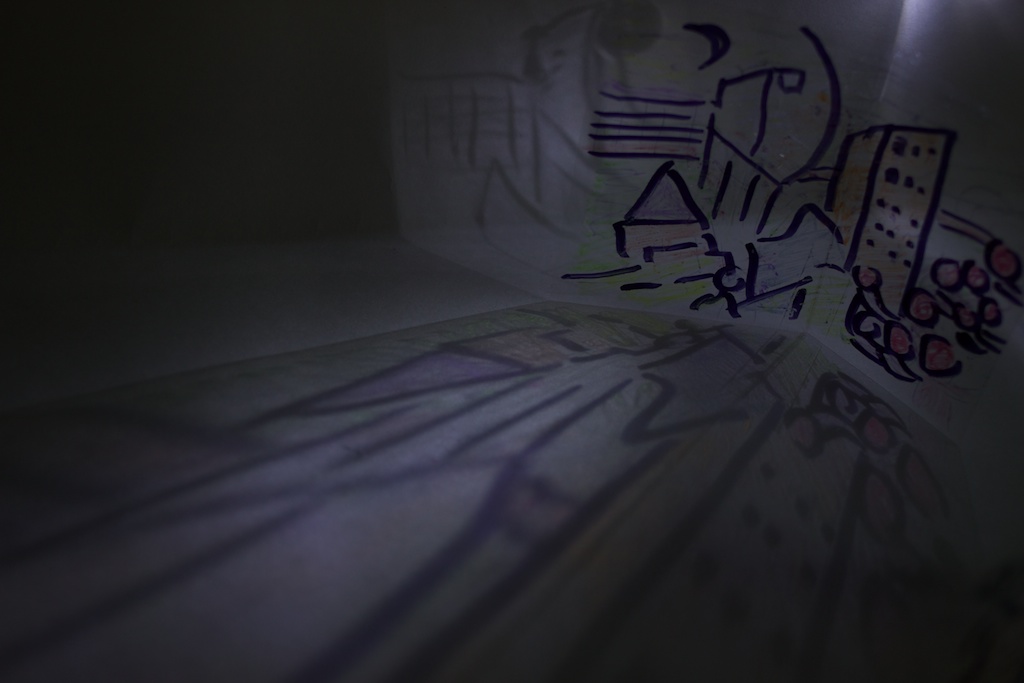

I have struggled to talk about Grenfell because I am an artistic "witness." I made a deep connection with the estate and its gardens several years before I started working here on an art residency. When I was officially contracted to produce a film and mural in 2015, several residents kindly opened their front door and hearts to a stranger. I navigated a delicate path between authorities and residents at a time when the latter were in dispute over the tower’s regeneration. After the tragic event in June 2017, I handed over all my photos and films to the police as part of their criminal investigation. I gave a witness statement. As we try to understand what happened at Grenfell, artists and film makers will all have a challenging but important role to play alongside the media. I’m trying to objectively recall how I approached making art on the estate when I was commissioned by the TMO (Tenant Management Organisation) to create a tiled art work and short film. The TMO were impressed with my V&A Museum and RIBA funded residency on Silchester Estate. I convinced them that an open-ended, durational process would work far better in delivering the outcomes rather than the original two weeks envisaged. As it transpired I was on the estate for approximately 1 year 2 months. When the time is right I will talk about the film, The Forgotten Estate, in more detail. The original plan was to design a large tile art work to cover an area approximately 3.6m wide by 2.2 m high in the newly formed ground floor entrance at Grenfell. This was to be created with the residents and children of the tower block. I was given a completely free brief as regards design. I decided to use large scale drawings as the blueprint. But as the drawings were so impressive in their own right, I decided to just stick with that as the completed art work. In total, 4 large scale drawings were made in the temporary lobby, on the elevated concrete deck just outside the tower and during the Grenfell fun day. The design for the art work was inspired by the classic blue and white willow pattern used in pottery. I was constantly sketching in the ceramic gallery at the V&A where this pattern had caught my eye. I always envisaged using an image of Grenfell tower in the completed design and perhaps to have this framed by an equally large tree. I saw a flock of birds in flight as representing the residents energised by their newly renovated building. The sessions with the kids would allow space for their own images and experiences to be added. That was the plan. As it transpired, the most successful drawing was realised at the Fun Day. The Grenfell Fun Day on 30 May 2015 was held mainly as a form of respite from the conflict taking place during the renovation. I was invited to attend and hold a workshop. A teenager looked at a blank sheet of paper. "What do we draw?" "Absolutely anything you like." Most children had the desire to draw or write what came naturally to them. The tower block they lived in. A girl picked up a leaf and sketched this. Animals started to appear. One wrote the memorable words: live, laugh, love. The cultural identity of the children also became a point of self-reflection with a Moroccan and British flag. The outline drawing in oil pastels was made by approximately 20 children and I then coloured it in. The art work then fell into a state of limbo. I had shown it to the TMO who were happy and also took it to a residents meeting. This would prove to be my last engagement and memory of the estate in May 2016. In the middle of that meeting, shortly after I had talked about the art work, one of the residents had challenged me over my film and this annoyed another resident, whose tense relationship with each other I had observed before. They then had a fight, then and there, in the meeting at which children were present. It lasted for about 5 minutes. Blood had to be cleaned off the walls. I believe they shook hands shortly after. I could understand how the residents were wanting to get on with lives after the huge impact of the building works. But the TMO? Why didn't they contact me again to hang the art work in Grenfell? I can only assume they were not pleased with the way my residency had developed, especially in terms of the film project. I held onto that art work for a year. After the fire it assumed importance as a visual and textual testimony to a destroyed community: Live, laugh, love. I'm pleased that this has been handed over to Grenfell United and is in the new community space for survivors and the bereaved. I have now started work back on Silchester estate across the road from Grenfell. After the anniversary of the fire, we will hold an Open Estate Garden weekend on the 30 June and 1 July. This will display the art created by residents. I have plans for a dance or performance piece facilitated by Dance West, although this might have to be staged later on in the summer. Over the years I have self-published photo books as well as making hand crafted books. I have increasingly turned to the latter as a means of reflecting on my engagement at Lancaster West and on the people I met and befriended. I am constructing my own self-questioning narrative. Did I make the right decisions in terms of my engagement? How will my imagery and art work be reproduced and the film footage help with any inquiry or criminal proceedings? Above all, how can I help the victims and community? I know that this was a "voiceless" community that nobody really listened to. I have also thought about my interaction with the press as they strive for the dramatic and poignant human story as well as the political message behind Grenfell. During the previous 9 months, I have developed an inner artistic voice that has kept the media, by and large, at arms length. These books, as I turn the pages, are part of my opening up. Imageless and Voiceless Booklets, 32 pages each, 2018 Oil pastel drawings, 5.5 x 4 inches Just heard about Grenfell Tower. Ghastly. What on earth went wrong? I was wondering if we could get this picture to do a story on. I would be very grateful if you could give me a ring as soon as possible to discuss an article I am working on for this weekend. I am the Dangerous Structures surveyor on the tower following the incident. If you were involved in the original construction it would be good to talk or meet you to discuss how certain elements work together. Constantine, various journalists have tried to contact me but I am not responding, so I would appreciate your confidence and not pass on any of my contact details. I don’t want him to think I’m stalking him! I don’t actually need him to discuss the fire. It is the building we are interested in and the original vision. One thing I'd say is that if we want to tell this hugely important story then now is the time, before the world moves on to the next headline. We have three million readers worldwide, a lot of them policy makers. Do please let me know if you change your mind. I am contacting you in relation to a live broadcast we are holding tomorrow evening. The event will consist of an audience of local Councillors, residents, firefighters, volunteers etc. If this is something you may consider being a voice for, please let me know. I do totally understand your reticence to give opinions on the matter, but could I trouble you with a quick question – do you know of any nearby towers that have a similar interior, i.e. common parts and layout? We are not tabloid journalists in for a quick story. We do very considered films on very difficult and distressing subjects. Thanks for the clear details in each of your blog posts. In an attempt to lend a little assistance from afar, a group of us have been building up three Wikipedia articles [[Lancaster West Estate]] [[Grenfell Tower]] and [[Grenfell Tower fire]]. Please go to these pages and tell us of any inaccuracies. I would rather use an image that speaks to the life in the community rather than awful images of destruction and tragedy to publicise the auction. The last thing I would want to do is appear to sensationalise the suffering of so many people. If you do have a change of heart, let me know. We would happily make a £200 donation to a Grenfell charity for use of your images. Dear Mr Gras, the V&A have been contacted by the Detective Constable from the Art and Antiques section of the Metropolitan Police in connection with the Grenfell Tower enquiry. She is working on the construction side of the investigation and has been tasked with identifying and contacting every company who may have information about the construction or refurbishment of Grenfell. I'd like to ask some questions on a positive note. I'm not press or politics. I knew that building was fundamentally safe. I'd really appreciate some answers regarding.... Sorry I can't say here.

0 Comments

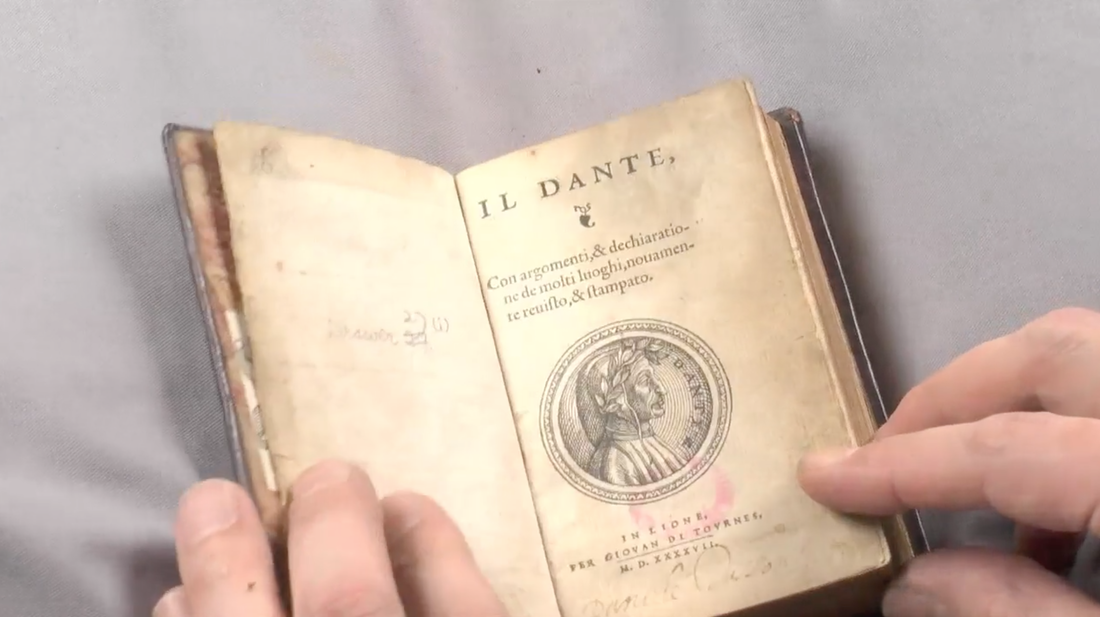

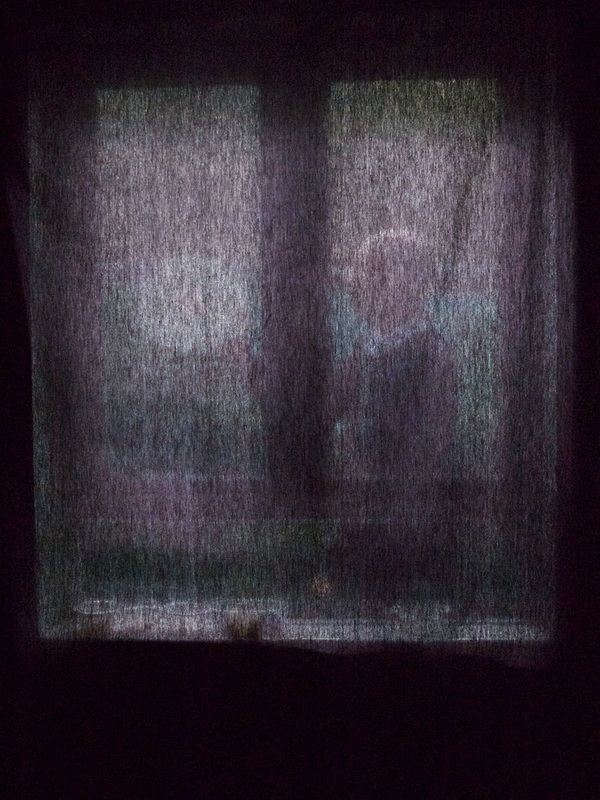

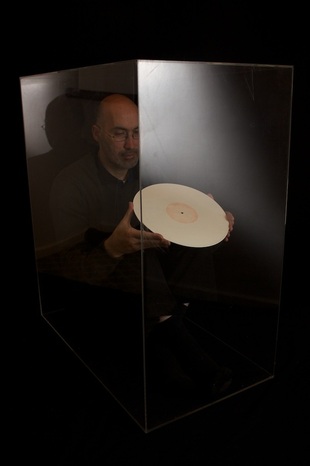

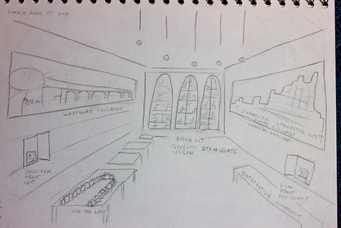

There is a corridor sized gallery at the V&A that I am forever drawn to. Literally, in the sense that I love sketching here. It's the Sacred Silver & Stained Glass collection in room 83. During my tenure as the museum's community artist in residence, I used stained glass to meditate on contemporary housing issues. Nathaniel Westlake's magisterial panel at the V&A, Vision of Beatrice, inspired an installation and artist film. The Westlake stained glass panel was made for a V&A exhibition in 1864 and was possibly conceived in the house that Westlake had built for him in the heart of North Kensington. The house is still standing at 1-2 Whitchurch Road opposite the Lancaster West estate and embodies the complex history of social change from the extremes of Victorian affluence and poverty to modern day regeneration and gentrification. This listed building would be a multi-millionaires paradise but has been converted into six bedrooms by St Mungo's and is a hostel for those needing support into housing and work. The house was situated just across the road from my artist studio which itself was a former council flat about to be redeveloped into More West. During my residency, I recorded an interview with Terry Bloxham who is a ceramic and glass specialist at the V&A with responsibility for the stained glass collection. I wanted to understand more about the context in which Westlake had made his stained glass panel and Terry quite rightly took me back in time. I was surprised by how the past would resonate so strongly with the way we live today: the forging of nation states; how religion can violently divide and spiritually unite; and the evolving technological and economic context to the making of art. Here is an edited transcript of our coversation: Terry Bloxham: Why Westlake? Why that panel? Constantine Gras: Why that panel? I didn’t know anything about it until I started my V&A Community Artist residency. I’m based in a studio in North Kensington that is part of an estate, the Silchester Estate. It’s part of a new housing development taking place on the estate. In the run up to my residency, I cycled around the borough, looked at listed buildings and I came across a house, just across the road from where my studio is. It’s the house that was built for Nathaniel Westlake. TB: Oh. Who be he? CG: It’s a bit of a juxtaposition from the estates. You suddenly see this listed building that was built in 1863. It was built by his friend and architect, John Francis Bentley, who later went on to design Westminster Cathedral. And they were both converts to Catholicism and collaborated on St Francis of Assisi church on Pottery Lane in North Kensington. But I was interested in this grand looking house near an estate and that's now run as a sort of hostel. It’s had a bit of a checkered history as this area of North Kensington has. Poverty and slums. Now property that is valued in the millions. TB: Where is North Kensington? CG: This part is opposite Latimer Road tube station. TB: I think I know. Basically Notting Hill west. CG: That’s right. TB: I know that neighbourhood. There’s a great reggae shop. Hopefully it’s still there. CG: So that’s how I came across Westlake. As an artist with a studio in the same area, albeit in a different century, I’m very interested in predecessors and making connections with them. And to discover that the V&A museum has a work of art that has a connection to the very streets in which I'm working. I’m also interested in a film that was also made in the local area and this is called Leo The Last. It was made in 1969 by John Boorman on the site of Lancaster West estate just prior to it being built. It’s about an aristocratic person who moves into the area and he gets radicalised by his interaction with the West Indian community. Some memorable imagery in the film involves looking through a telescope and also patterned glass in a pub that distorts the point of view. I suppose at one level, I wanted to explore or create a connection between film making and stained glass. In the sense of camera lenses and glass transmitting light and how they might be used for perception and analysing or documenting the world around you. Using fragments or a diverse range of media that can be pieced together to make a whole new work of art. And one not necessarily made just by the artist, but involving collaboration. Also I feel a little like that aristocratic character in the film. The artist as an outsider who comes into an area and interacts with the community and how this might radicalise either them or the community or not as the case may be. That is the type of thing I’m wanting to do in my community focused project work. I’m hoping to create a Westlake House at the V&A Museum, in addition to making an artist's film. TB: Brilliant. CG: Perhaps you can help me shed some light on Westlake and how and why he came to make this wonderful panel. TB: Westlake in the nineteenth century, is, near enough, the culmination of a movement that we now call the Gothic revival. And the Gothic Revival was a reaction against eighteenth century stuff and we are going to be talking about that as we progress through time. This involved a revision in the theological understanding of Christianity and also the furnishings of Christian churches. And all throughout the gothic revival period, whether you are talking about stained glass or metalworking or textiles, all of the things that were used for church furnishings, they kept harping on, we must do it in the medieval manner. And that’s why you’ve got to understand the medieval manner in order to understand Westlake. That’s why we are starting here in the medieval period. We are looking at thirteenth century glass. CG: Was this being commissioned by the church? TB: Yes. it was church law that you had to have some sort of decorative, figurative work in the church, that illustrated the Saint to whom that church was dedicated. All images in churches were meant to be instructive. People always say it’s bibles for the poor. But that’s sort of an insult, because it’s calling them illiterate. And I prefer to look at it, not as an age of illiteracy, but as an age when you didn’t need to read and write. Only a few people did. In the middle ages, TB: So here we are looking at a panel from the mid thirteenth century showing a scene of King Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus or Jermaine. It is telling you a story, an episode from the life of a real king. His name was Childebert. He’s in the middle of the sixth century and was one of the first kings in France. After the collapse of the Roman empire in the West you have all these so called barbarians moving in. You can tell my preferences lie with the so called barbarians. Various tribal groups as they were known: the Goths, the Gauls, the Francs, the Germanys, the Celts. The celts became the Brits. These groups are going to form our nation states. Clovis was one of these Frankish groups and from Frank we get France. This is where Childebert is descended from. In the panel, we have Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus, the first bishop of Paris. He is chastising the King because he had just been on a campaign to conquer the Spanish city of Saragossa. The bishop was upset about this because Saragossa was a christian city. Bishop Jermanus forced Childebert to build the first church in Paris as atonement for his sins and this church was dedicated to St Lawrence. This church was being rebuilt in the thirteenth century in the newish Gothic style and it was rededicated to Jermanus who by then had become a saint. CG: Can you tell me about the designs used in stained glass and the process of making? TB: Medieval decorated windows are composed of small, irregularly shaped pieces of coloured and clear glass. The idea was not to have big square panels of glass which they could make, about A4 sheet size. It was to make a sheet of glass, cut it into irregular shapes and move those shapes around to form a picture. And then those shapes are held together by lead. So it became known as a mosaic-type construction. When you think of a Roman mosaic floor, little pieces of tesserae arranged to make a picture shape. And then they are embedded into cement to form a solid picture. It’s the same thing with mosaic glass. The only painting that you have on it are the details that you can see in the hands and the face, the folds in the clothing. That’s just simple blacky-brown iron-based pigment which is fired onto the surface of the glass. Glass when made is clear. But in its molten state you can add colouring agents to it. Cobalt will make blue. Copper will make green and also red. Manganese will make a purply brown. Depending upon the intensity you can get this nice purply-brown robe or flesh colour. That is know as pot metal because you hold the liquid glass into a pot and add the metallic oxide. So you have clear glass and pot metal glass, cut into small irregularly shaped pieces, put together to make a nice, pretty little picture, all held together in this lead framework. And whatever paint you have was just an iron based pigment onto the surface of the glass to give you your details. That is mosaic glass made in the medieval manner. That is what Westlake is trying to achieve. I have to introduce another element in the manufacturing of medieval glass. Something that was a big technological revolution. I mentioned earlier that properly speaking, it’s not stained glass, it’s decorated glass. And the reason why I say that is because stained means penetration of glass or staining glass. That doesn’t happen until the magic year of about 1300, probably in Normandy. Some bright spark discovered that putting silver into oxide of some form and then firing, what it did was to penetrate the upper levels of the glass and create this lovely lemony yellow to a burnt orange colour. And the reason why that was so revolutionary was it enabled you to have more than one colour on the sheet of glass. We looked at yellow glass and red glass and blue glass and green glass that is known as pot metal glass. That is clear glass that has been coloured. Coloured glass is more expensive than clear glass. Any time you have extra processes it’s going to increase the price. We do have those few surviving documents that give us prices for the middle ages. So we know that glass coloured all the way through was more expensive. Staining it is incredibly cheap to make relative to the older way and once it comes in, it doesn’t disappear. When we get to the Reformation in the sixteenth century, Europe is torn apart by different believers or practitioners of the Christian faith. In the middle ages, remember there is only the church. There is no protestant, no catholic. It is just the church. So you have to put yourself in a time when your world, your faith is being torn apart, is being questioned by people who are very learned and very persuasive. And in some cases also inciters of violent activities and feelings. We tend to blame the whole reformation on him, Martin Luther. He was pretty moderate. You also had people like Calvin and Zinger who were the militant side of the reformation. And there was a lot of destruction and a lot of change. But in Europe today, you will still find this part of Germany is Catholic, but that part is Protestant. But fortunately not fighting each other. England’s story is different and was more violent. Not so much people killing each other, but people destroying anything suggestive of religious imagery. CG: You get a snapshot of those times at the recent iconoclasm exhibition at the Tate. TB: Yes that was a good snapshot. And we also have documents from stain glass makers, petitioning the local leaders of the city, the principalities. Saying you are putting us out of business. We used to make a living making religious windows for churches and it was just no longer allowed. On the continent they started to turn their hands to other iconographic subject matter in stain glass making. TB: What we are looking at now are products of Netherlandish workshops who mastered from the fifteenth century onwards, the art of very fine, but mass and cheap production of glass windows. These are simple pieces of cylinder glass, cut into a circular shape and solely painted. So its clear glass, in silver stain and black pigment. They are cheap. They are incredibly finely painted because this is the age of the printing press. So engravings were made and then they would be printed and they would be used as models for these stained glass workshops. So infect they’re copying exiting art works, unlike in the medieval period where they don’t have the benefit of mass produced engravings and stuff to copy. This panel is the story of Sorgheloos which is a secular version of the old testament story of the prodigal son. This guy, Sorgheloos, goes out, he inherits a whole bunch of money, spends it on wine, women and song. And in the end, all he has left is an old woman, two starving animals and a bunch of straw to eat. So unlike the prodigal son he’s not welcome back with the fatted calf. What also happens in the middle of the sixteenth century, these chemists as we would call them today, alchemists as they were known, developed more pigments that could be fired successfully into glass. In the medieval period it was just that blacky-brown iron based pigment. Now we have enamel colours. So we have the greens and all the shades. Red and all the shades. Blue and all the shades. And the yellows. CG: It must have been a wonder to behold, a sort of technicolour movie. TB: Yes it was. That’s why they were popular. Also coloured glass was expensive and enamel paints are cheaper than coloured glass. So we are now in the age of just simply painting on glass. Think of it as a transparent canvas. Because that is where we are going, painting on glass. Let us jump forward to the middle of the eighteenth century. We have aristocrats interested in the gothic. Walpole made Strawberry Hill which was his idea of Gothic. And then In the early part of the nineteenth century we start getting academics in Oxford known as the Oxford movement. They were also called the Tractarians because they produced a lot of tracts. They are looking at medieval theology and seeing it or pre-reformation theology as a more pure form of the Christian faith. They are not advocating a return to catholicism but they are advocating breaking away from the corruption that crept into the English church in the eighteenth century. Shortly after, a complimentary, although at times, rival group, grows up in Cambridge known as the Cambridge Camden society, but also known as the Ecclesiastics when they are sitting in London. They were interested in pre-reformation theology, but more importantly in pre-reformation architecture and church furnishings. So you have in Oxford, the academics looking at theology. In Cambridge, they are looking at the physical structures of the furnishings. So we are at the beginning of the nineteenth century at that time when people are looking back to the medieval world and things done in the medieval manner. So this is where the Gothic Revival begins. Also in 1824 the Government passes what became known as the 600 churches act. Christianity had fallen into corruption in the eighteenth century. The church fabric itself, the buildings were neglected. There were a lot of people assigned as clerics in churches who just stayed in their country estates and took the money and they didn’t even maintain the churches. So the government steps in and makes a proclamation, effectively going, thou must build churches. Into this comes the great architects like Butterfield, Street, Pugin. So the very first half of the nineteenth century is what we know as the Gothic Revival. Church building, church furnishing going on and stained glass starts apace. Also in the 1850s and 60s craftsmen were thinking why can't we do it like the medieval stained glass makers. They couldn't simply because medieval glass is mouth blown. So there is no evenness in its thickness. Each bit of glass that the medieval craftsman made, this bit is thin at one end, but it might be thicker at the other. So that when you put it into a window and light comes through that little bit of glass, the light will come through differently. It will be less bright in the thicker bit and more bright in the thinner bit. The medieval craftsmen knew that. That's what the Victorian stained glass makers were really trying to discover. TB: Nathaniel Westlake was a freelance designer. You could make a living by doing that. He went around to companies like Powell’s who were probably the biggest manufacturer of windows at this time. He would show his portfolio of how good an artist he was. Also a portfolio of stained glass design that he could offer to them. And that is how he was making his living. But in about 1858-59, clearly by 1860, he had become involved with the stained glass firm of Lavers and Barraud. In 1864 the V&A had an exhibition of stained glass and mosaics and one of the firms that submits things that were selected to be displayed was a panel made by Lavers and Barraud to the design by Nathaniel Westlake. So this is just made for an exhibition piece as far as anyone has ever been able to find out. It wasn’t actually a potential commission which a lot of exhibition pieces were. This just seems to be solely their own making and as it’s a design by Westlake, one makes that big assumption that it’s Westlake’s idea. The iconography of this panel was all in his head. We know that Westlake was friends with the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood like many groups in Europe were interested in things medieval. They’re looking at more literary subjects. Morris and co were doing lots of things like George and the Dragon windows. Dante Alligheri, the writer of the famous Divine Comedy, from the early part of fourteenth century was big. There was a lot of interest in him. The iconography of the Westlake panel is quite complicated. It is derived from Dante’s Divine Comedy. In this poem Dante was granted a trip through hell into purgatory and finally into paradise. It’s a wonderful story. Dante is lead by the Roman poet Virgil who to him represents reason and as Dante is going through hell and purgatory he is reflecting on his own life. He is working out his own sin. At the very end of purgatory, this person called Beatrice starts to be mentioned. Beatrice was a real person, Beatrice Portinali. It seems that Dante knew her when they were children in Florence. He was a member of one family and she was another. For whatever reason and remember Italy wasn’t a unified country, it was a bunch of city states and these city states had noble families fighting each other. So marriages were not love matches, they were political matches and Dante had fallen in love with this young Beatrice. Madly, head over heels, quite perversely. Like, get over it Dante. But he never did. But he couldn’t marry her. She married someone else. We don’t even know if she realized his devotion. But anyway she had to marry someone else and she died quite young. So he was stuck on her all this time. Now when you read the Divine Comedy it becomes apparent that Beatrice is divine love. And divine love is the only way you can go through heaven. Reason cannot take you into heaven. So at the very end of purgatory, before he makes that last crossing of the river and going up into heaven, Dante is given a vision by a woman called Mathilda and her companions, often known as the three graces, but really faith, hope and love. They give Dante a vision of what is to come. And this is the first time that he realised that this woman, who he has always loved and is now dead, has become divine love. This vision of Beatrice is going to lead him into paradise. This is what is depicted in the panel designed by Westlake. Beatrice up there in that top left corner. Faith, hope and love are those three figures who are often referred to as the three graces. First personified in that form by Sandro Botticelli in the middle of the fifteenth century in the Primaevera painting. This is Dante kneeling at the front, eyes closed, given that vision of Beatrice. That moment when he realises that his love has become divine love and so will take him into heaven. It’s done in the medieval manner. So we’ve got little pieces of glass just like in the medieval way, irregular shaped pieces carefully chosen. It’s not just take that one, put it there to make the picture, but trying to get the right balance of light coming through. By this time in the nineteenth century they are using the equivalent of light cables. So they can start to see the effect and so they can choose the glass, arrange the shape in order to maximise the light coming through. So Westlake is the culmination of this late eighteenth century, first half of the nineteenth century, Gothic revival way of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval craftsman. He is a medieval artist. Let’s put it that way. Lavers and Barraud are a workshop that operated in the same way as a medieval workshop would have done. You have a centre in which you had your designer, your painter, your glass maker, your lead worker, all in one institution producing the window and each one being prized for their skills. As the nineteenth century moves on the designer becomes more of an artist. You start to get into, what is known in the ceramic world, as art pottery. You might as well call it art stained glass. Four film stills from Vision of Paradise, 2015. 30 minute, high definition video.

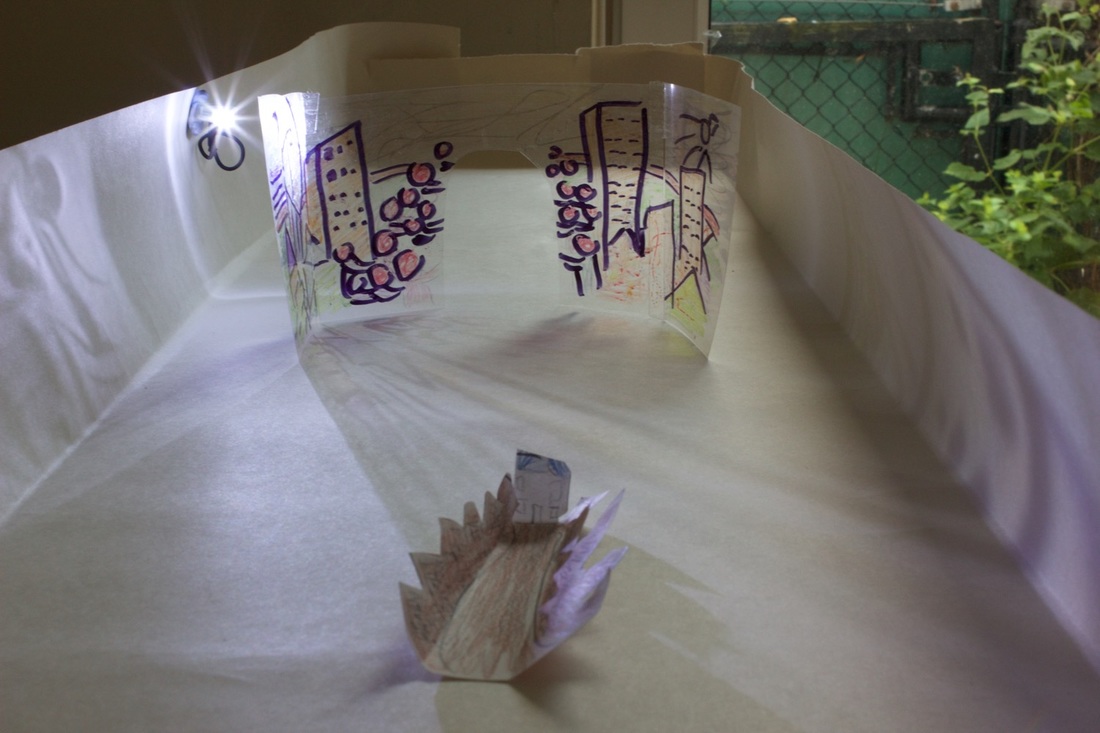

The entrance to the Architecture Gallery at the V&A has a classic marble staircase. It echoes to the sound of history. On the 19th and 20th November 2014, I held a film screening and paper folding workshop here. Visitors approaching the space would have heard the following sounds and voices. Fragment 1 The sound of WW2 bombing, glass shattering and the percussive dub of the Notting Hill Carnival. This reverberation in a usually quiet location caused a few raised eyebrows and the volume had to be scaled down. Fragment 2 North Kensington residents reminiscing about good and bad days, post-war poverty, multicultural experiences, poor housing and the British sense of humour. An American who lives in London and who viewed this section of the film programme commented about the shocking poverty and how in the good U.S. we never had it so bad. Fragment 3 A filmed conversation with Joanna Sutherland, project architect at More West housing development. This is where I am based as V&A Community artist. She talked about: "What we are seeing ... is the threat to communities due to the expense of living, not just in central London, but all areas of London. I think there has been a growing interest in the last ten years, if not longer, of how communities evolve and what's important within a community, whether it's through schools, a community facility, a church. And I hope that this project, Silchester and the wider area, still remains a home for those who have lived there, had children, and maybe they can continue to live in the same place." It was heartening to hear positive comments about this film from residents of the estate currently undergoing transformation. A new community is forming at More West built on the foundations of the previous slum clearance redevelopment in the 1960s. That phase of development was very disruptive coupled as it was with the building of the adjacent Westway A40. It did however create social housing. Today, there is no longer a desire to match that social vision, and what is affordable in terms of rent and quality of life, is beyond the means of many. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and Peabody are providing part social and market housing at More West that consists of 45 rented homes, 39 shared-ownership and 28 for outright sale. The new housing is part of a rapidly changing area. However as our local councillor states: "There are too many poor people." Councillor Judith Blakeman has to deal with many of their social problems. Fragment 4 Glockenspiel and assorted drum kits provide a positive vision of the future. Children from Frinstead House are drawing. A girl illustrates herself waving goodbye to her father from the 20th floor of the high rise; he is waiting for his train at Latimer Road tube station. Another child mischievously draws a giant t-rex attacking the tube station. This is regeneration, disaster monster movie style. Yet another child provides a rainbow arcing across the skyline. This was one of my most direct and rewarding engagements as community artist. I did not advertise this. I merely set up a large sheet of paper in the foyer of Frinstead House and invited local residents to accompany me in filling the blank. Adults and children confirmed their cultural identity and what it means to live in their high rise homes. Fragment 5 - Was not heard at the museum. It has not been caught on camera or in any of my expressionistic documentary work. I hope to render this shortly. Symbolised by a DJ playing at a recent marketing event for More West. He has bought a flat and will move to the area in 2015. He is excited. Young and professional. For him there is no lingering doubts. He is forging the future in progressive sound waves. Zeitgeist. In summary, this curated programme had the aim of dialectical montage, the juxtaposition of contrasting images and sounds. This is our experience in all its complicated social modes. It is both beautiful and ugly. We build for the future and paper over the cracks. Speaking of paper (workshop), I have also provided a visual record of how young and old came together at the V&A Museum. Complete strangers who with a little encouragement and artistic structure are able to express light and shade, twisting new shapes into being and creating another fragment (like no 4 above) that brings a smile to my face. Outside the builders are laying bricks and installing windows. In my studio all is calm. I've been in listening mode and am currently transcribing two audio interviews.

The first was with Joanna Sutherland, Associate Director at Haworth Tompkins and project manager for More West housing development. It's fascinating to hear her talk about the visual appearance of the building taking shape opposite Latimer Road station. She explained the significance of a special Dutch brick called Bronze Grun. "The appearance of the brick, the tonal variation across the brick and the right mortar colour are absolutely crucial to the success of the project." It was not however easy to replicate trial samples and meet the original planning requirements. "We were in no way going to allow anything to go through that wasn't perfect. And if you look at mortars, different mortars of brick, it completely changes the appearance of the brick. So even now when you still see the area that has got the salmon pink, you can see it's a nice brick, but it doesn't look very good. And where the mortar's right, it looks fantastic." My second interview was with Terry Bloxham, Assistant Curator for Ceramics and Glass and the V&A. She gave me a superb tour of stain glass from the medieval period to the present day. This provided context on a Nathaniel Westlake panel, The Vision of Beatrice, that I'm using as inspiration for my project designs. "Westlake is the culmination of the Gothic revival. Of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval artist." "In the panel we've got little pieces of glass, careful chosen. It's not just take that one and put it there to make the picture. But to get the right balance of light coming through, maybe the ones on the bottom are thicker, thinner at the top. Before you put it all together in the lead framework, other techniques are used, like painting, and staining and etching." The Vision of Beatrice illustrates a scene from Dante's Divine Comedy. This is the climatic moment when Dante's love has become divine and he can be transported from purgatory into heaven. Recently, I met buyers of one and two bedroom flats at the development. Young professional workers who were excited about moving into the area. They wanted to know about local facilities and views from their flat. I could comment on the former. Hopefully they were pleasantly surprised to hear about the the complex social history of the area and having the Notting Hill Carnival right on their doorstep. I wonder if they will experience divine love (or otherwise) in their homes. Let us hope so. Future artists and historians will interpret and tell a story. In time. No Object My studio is a 1966 council flat that has no domestic furnishings. I invited visitors to bring an object from home and to tell me a story. Many thanks to visitors and participants in No Object. You brought my studio to life for a day with your stories about a milk and marmalade pot, harmonica, Big Ted, Aboriginal art and 8mm projector. Together we made the film, No Object. Event comments Nahid, Silchester estate resident: "Amazing insight to the area I've been living in for over 30 years." Neil Hobbs: "What a wonderful project. I hope this is happening all over London. If not, why not? This social history is so very important and should be recorded." Lucilla Nitto, photographer and W10 resident: "Very interesting mix of space and art. Well done!" No Object was held as part of the Portobello Film Festival and consisted of:

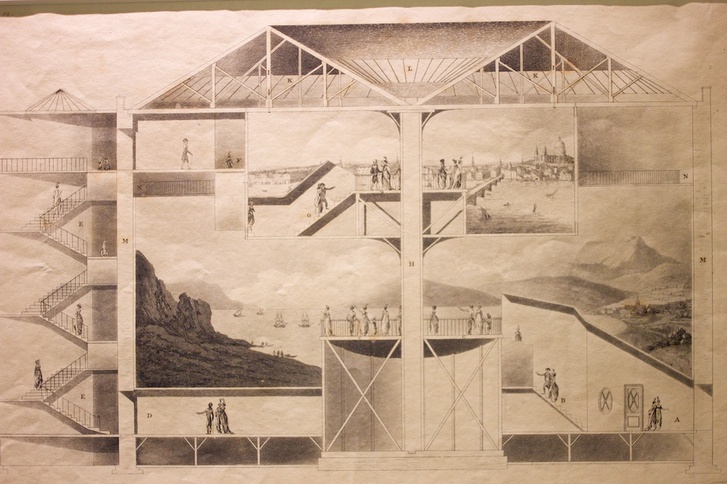

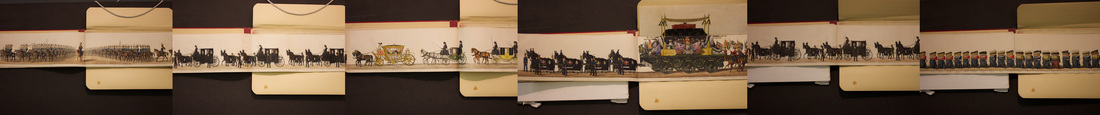

Exhibition notes The gritty streets and houses of North Kensington have attracted film makers since the 1950s. In The Blue Lamp (1950) a classic cops and robbers car chase along Ladbroke Grove ends with a car crash near Latimer Road. In the following year, Ealing Studios, provided a neat comic variation to the chase. In The Lavender Hill Mob, two police cars crash at the juncture of Bramley Road and Latimer Road outside the Bramley Arms. Their car radio antenna become entwined. The resulting incongruous broadcast of “Old Macdonald had a farm and on this farm he had a pig” resonates deeply with the history of the area, noted for its pig farming in the 19th century. This part of the Hill is known locally as Notting Barns or Dale. It consolidated its seedy reputation as a “slum” with four days of race riots in 1958. Ethnic tension would feature in Sapphire (1959) with a scene directly culled from press accounts of the riots. A black suspect is chased by the law from a club in Shepherds Bush and is assaulted by Teddy Boys in Notting Dale. He is saved by the actions of a local grocer woman. Fact made fiction. The race riots provided a poetic framework for the book Absolute Beginners (1959) written by Colin MacInnes. In this seminal novel about the youth culture of the day, the writer had this to say about the area: “A long, lean road called Latimer road which I particularly want you to remember, because out of this road, like horrible tits dangling from a lean old sow, there hang a whole festoon of what I think must really be the sinisterest highways in our city, well, just listen to their names: Blechynden, Silchester, Walmer, Testerton and Bramley..........and there’s only one thing to do with them, absolutely one, which is to pull them down till not a one’s left standing up.” This was a prophetic statement as the houses and streets were all torn down for the building of the Westway (A40) and council estates in the 1960s. A musical adaption of Absolute Beginners was made in 1986 featuring David Bowie. Kitchen sink dramas of the 1960s would also tap into the poverty and housing inequalities of the area. When Bette Davis visits run down Walmer Road in the 1965 film Nanny, she discovers her estranged daughter is dead. A result of a back street abortion gone horribly wrong. This pushes her character over the gothic edge. Far more sinister happenings would take place at nearby 10 Rillington Place. John Christie, the serial killer, would offer deadly medical assistance to vulnerable women. The late Richard Attenborough powerfully conveyed Christie in the 1971 film version of the case. With the building of the Westway and the estates, new possibilities for filming road sequences would appear. When Hammer made The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1972), it seemed fitting that they should use the redeveloped Bard Road, just off Freston Road (formerly Latimer Road). This was and is a dead end road behind the Harrow Club. In the film, two biking Hells Angels trail a secret service woman and kidnap her at this point of no return. Radio On (1979) came out of left field. A black and white film about alienation and featuring the modern existential drive. Not at street level, but above on the turbo charged Westway. Adulthood made in 2008 by a new class of film maker, Noel Clarke, captures all the angst of life on an imaginary estate. The culture of young people who are trapped in the vicious cycle of gang crime. The police from The Blue Lamp are nowhere to be trusted or respected. The bad guys are the good guys you root for. The film uses locations in North Kensington that could be located in Silchester or Lancaster West Estate; these stand on either side of Bramley Road and Latimer Tube Station. This council flat at 7 Shalfleet Drive is part of the 40 year old Silchester estate. It will be demolished in January 2015 to make way for mixed-tenure housing. As resident artist based here, I will be making a film project about the new housing development and the new community that is forming here. Looking to the future, I wonder what films will be made in this area over the next 50 years. Will they replay good cops, bad cops? Will poverty and housing issues still feature? Will more diverse multi-cultural voices be heard? Will there be estates dominated by a new middle-class criminal? Will the narrative film form, the staple of generations, become obsolete in the new social media age? Leo The Last art project Leo The Last is the definitive local film that resonates with the themes of my residency: housing, architecture, film. Leo The Last was directed by John Boorman in 1969, between his Hollywood films, Point Blank and Deliverance. The story concerns a European aristocratic landlord who moves into a slum area of Notting Hill and becomes radicalised by his oppressed West Indian residents. The film is an experimental adaption of a stage play and Boorman chose the location because of family links with the area. Uniquely, the design team were able to use a local road, Testerton Street, prior to its regeneration into the Lancaster West Estate. Nearly all of the residents had been moved out and Boorman was able to paint all the houses and road black. This created the unique monochrome colour palette in the film. A false house was built across Testerton Street. This was the stuccoed white house for the central character. In the archive, I came across the touching story of one couple, still living on the road at No 27 and waiting to be rehoused. Arthur and Grace Clark refused the offer of £50 to have their terrace house sprayed black. “We could do with the money really,” said Mrs Clark, who had lived all her life in the house. “But if we agreed to let them paint our house, the vandals would get busy, as they would think it’s empty.” I am working with the V&A Museum to screen the film for residents at Silchester and Lancaster West Estate. They will then help me to make a ceramic installation based on images from the film. It might not be the final frontier. But this blog entry begins and ends with space. The big bang of the widescreen, large format and panoramic. A location for an artist to perform and connect with people. The contested politics of space, building homes and forging communities. First stop. Let me beam you to my non residential artist's studio. All artists cry and bleed for a space. This is nothing new. East London currently rules the roost, but in the past artists would look to this stretch, west of London, for verdant grass and fresh air. William Mulready was one of the first artists to settle in Kensington in the first decade of the 19th century. He shared digs with fellow artist John Linnell at Kensington Gravel Pits and then had a studio house built for him in 1827 at Linden Grove (now gardens, the house is no longer extant). This was during the first wave of development for the Ladbroke Estate and Mulready lived here for the remainder of his life. Nearly forty years later, Nathaniel Westlake, having just converted to catholicism, has his architect friend, John Francis Bentley, design a house for him in Notting Barns. Westlake did not stay here for long. We can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. His house is still standing and looks out of place next to the Lancaster West Estate. Mulready and Westlake are both closely associated with the birth of the V&A Museum and have work on display. In terms of art, studio space and the V&A, I am following in their footsteps; more of this anon. During my V&A Community Artist residency, I have that precious commodity for an artist, studio space. I am not based at the museum like the other resident artists. I am a tenant of a flat whose rooms can be sculpted, wallpapered, improvised. It's an in-between space, a former council property, that will become part of a mixed tenure housing. No one will care if I artistically trash it as demolition is due next year. I'm conscious of being the last in line. Leo The Last. The last house demolished. I've explored these in previous art projects. Now. I'm living out my very own kitchen sink drama. What about the medium or mixed media of space? Artists are always grappling with this technical consideration, whether it's processing on a computer or via more traditional craft techniques. I usually compose an image through a viewfinder of a camera or a sketchbook often leading to 16x20 inch drawings; this is a legacy of working with photo paper formats in a darkroom. There are also multiple dimensions to my residency: how art relates to community and housing and architecture. As I want to share and encourage others to participant in these processes, I need to think big as in large scale. This is new to me and will present its own set of challenges. I also need to engage with my immediate neighbours on the street, residents in the estate, people in the ward, across the borough. An audience that might not understand "art" or perhaps even know who the V&A are. As I begin, so I end. Everything is hurtling towards a date in January or February 2015 with an end of residency event at the V&A. This is in the lunch room for visitors to the learning centre. However being the V&A it is no ordinary lunch room. It has a cinematic sweep, certainly from the top down. Even wall lined cupboards gets one thinking of spaces within space. I'm looking at constructing panoramic displays here, perhaps of the Silchester and Lancaster West Estate and its residents. This will include film of the new housing development taking place and the new community that is forming. Also perhaps a representation of the Westway (A40), a built structure that dominates this area of North Kensington. Can I also chuck in some "stain-glass" imagery for the aesthetic thrill? On August 18th I hosted an open day bringing some of these issues into focus. I did wonder how many people I could safely fit into the studio flat and its 4 spaces (20 comfortably at peak capacity). It was a good idea to convert a large store room into a history room with archive maps and images. In total, I had 60 plus visitors. Delighted to see my neighbours on Shalfleet Drive popping in to see what all the fuss was about. This is important as I plan on working with them on a film project. There was a group visit from Open Age who took to my live drawing like ducks to water. Great to see old colleagues, including Adam Ritchie who was pivotal in establishing the community ethos for the Westway and the building of play spaces for children in the 1960s. The Mayor of RBKC Maighread Condon-Simmonds also paid a visit. She is a charming lady, really down to earth and digs the complex layered history of this area. In her thank you letter, she chimed in with my thoughts about the challenges of space: "You have made a truly interesting display in such a small space.....The north of the borough has so much more space than the south and it is good to see the new developments with good quality homes." For the exhibition, I also created a drawing installation called House with 40 Rooms. In each room there was an object. These objects were all from the V&A. I invited participants to use words or images in response to the objects in the rooms. Local resident, Maggie Tyler, wrote the following about her drawing: "I used to look out at a Stag's Horn tree and a round window in the wall of the house at the end of the garden. At night, I would see the silhouette of the foxes walking along the top of the wall past the round window. Then! The Neighbour moved out and the new neighbour built an extension. A modern extension that covered and destroyed the round window. The tree fell down and the view has changed. I now look at a modern box!" A few days later, I opened my studio during the rain-sodden Notting hill carnival. Sheltering outside my flat, I took pity on a group of performers and invited them in. Amos has been taking part in the carnival for over 15 years and we chatted about its history which is reflected in art work on display. New residents moving into More West from 2015 (once the flat is demolished and new housing built) will find they are on the western edge of the processional route. There is intense debate about the future of the carnival. Is it too big for the streets of Notting Hill? Cllr. Eve Allison, who has ancestral roots in the Carribean, believes there are compelling reasons for relocating the carnival to a larger green space. This would be a tremendous loss to the area and signal a departure that the carnival has lost its community connection. Down at the V&A, I've been reflecting on this and artistic precedents for panoramic art. Nathaniel Weslake has large upright stain glass and oil paintings (with associated mosaic) on display. I've previously commented on his smashing stain glass. This time I'm checking out his contribution to the Valhalla portraits. It seems apt that Westlake should choose as his artistic role model, Fra Beato Giacomo da Ulma (d.1517), a Dominican Friar who painted on glass at Bologna and is an obscure figure in the series. As Westlake did for da Ulma, I will likewise do for Westlake. Celebrate the art and allow this to percolate into my practice. This means moving into unfamiliar territory, but I'm up for the challenge. I can start digitally with photoshop and a literal following in the footsteps (see image below!) This is a simple tool to collage ideas and feelings about the construction of a pictorial landscape. Just the first step in a process of ongoing experimentation that will probably morph into craft and film. In the prints and study room, I perused an 1801 plan for a panorama in Leicester Square. This was presented as various walking and viewing points in a space shaped by architect and painter. Ingenious. I also marvelled at the skill employed in a fold-out book made to commemorate the Funeral Procession of the Duke of Wellington in 1852. It was made by Samuel Henry Alken and George Augustus Sala. The pomp and circumstance of this stately occasion made an interesting contrast to the recent carnival floats that passed by my studio. It connects with previous thoughts about creating work that fuses the historic with the contemporary. My art musing is only of interest when it translates into practical application. How to use art to look at the urban environment, the community spaces around my studio and the homes that residents have made here? How high rise residents perceive the new developments taking place below them? How residents in the shadow of taller structures respond to changes in light and air quality as the sun climbs and then dips into the West? How do I create a space for public participation in the process of making art? How will others want to comment on the world around them? I need to bear in mind that this might not necessarily tally with how I view the world. How will art be elegantly displayed for a follow-up activity of engagement? Can I bring this all together at the V&A lunch room as food for thought? I don't particularly want to end on a question, so offer this as a postscript.

I'm being managed by Laura Southall in the Learning Department and it was great to meet more of the team. I set them a 10 minute challenge to make some sculptural forms and showed them a few examples. If they ended up making a posh version of a paper aeroplane, that would be fine. Dah! They do all work for the V&A, pre-eminent design and art museum. Fold, tear and sellotape. Horizons west. Feels good. Definitely settled in as Community Artist: collaborating with local art projects, connecting with the V&A collections and mapping out my own artistic concerns.

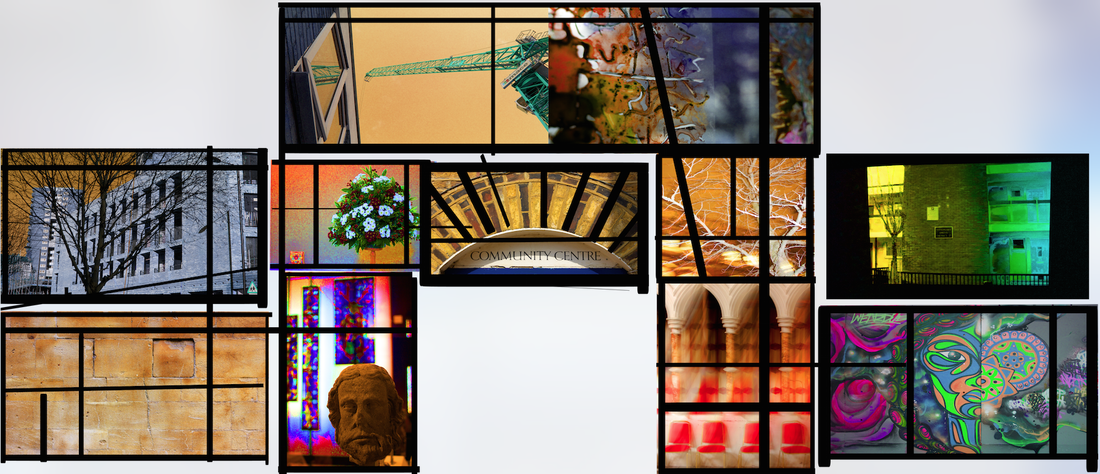

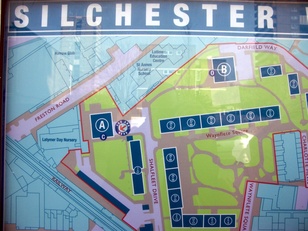

First off, spray painting at the Henry Dickens Court Community Centre. Local children working with TMO, Steph Perkins and lead artist, Claire Rye, have produced a great picture that will be attached to the hoarding of the building site at More West. It was good to see the design on paper turned into the completed image. Local artist, James Mercer had the amusing idea of incorporating Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; the building site has a female crane driver who works with an all male crew. There is never a dull or quiet moment at the studio. Although I've recently been diagnosed with otosclerosis, which is beginning to affect my powers of hearing, I'm constantly alerted to activity at the front of house and back garden. There are daily deliveries to the building site with large trucks stopping outside the flat. Last week, I was chatting to my Tunisian neighbour, Kacim, when a concrete staircase was being delivered. This looked very photogenic and I had to dash off for my camera; hope he didn't think me rude! Speaking of photography, I'm grateful to Liz Grant at RIBA for supplying books for my studio. Anyone interested in architectural photography, should check out RIBApix. Looking forward to viewing hard copies in their library. Natalie Marr from group-work also dropped off a recent publication - Staying Put: An Anti- Gentrification Handbook for Council Estates in London. The studio I'm based at on 7 Shalfleet Drive is a former council house connected to Silchester Estate. This side of the road will be demolished in January 2015 after the residents have moved into new property at More West. RBKC council and Peabody are providing 45 larger properties for social rent, 39 shared ownership and 28 for sale on the open market. There will also be a new retail unit, a community facility, public garden area and private communal garden with children’s play space. Two recent discussions I've had at my studio, have brought into focus the complex issues around estate regeneration and the affordability of housing. As an artist I'm located at the core of these changes to the built environment, reflecting on the impacts they might have on local residents and the potential they offer for the future development of the area and its communities. Never a dull moment. I opened my front door one morning and saw two women in the street. They asked about the new development as they were thinking of buying a flat. Mother and daughter, Sacha and Cecily, were duly invited in and later got to meet, Joanna Sutherland, who is the architect behind More West. They have a historic family connection with nearby Hammersmith. Cecily, the daughter, has rented in North Kensington over the past few years and is looking for a home near the Electric Cinema where she works. They expressed concern about "affordability" as the cheapest housing units to buy are £400,000. How will this also impact on the local area (primarily council estates) and the community being formed around the new housing? Another discussion: much more heated, not dull. I had a visit from Edward who lives at nearby Grenfell Tower. He has been involved in a campaign regarding the future of the Tower and the redevelopment of land around the Lancaster West Estate. The latter is providing a new academy and sports centre. His first words to me, roughly paraphrased were: "If you are not for us, then you have no right being here!" Pity the conversation was primarily one way. However I was troubled by the pain and isolation of Edward's feelings. This is a challenge for a community artist whose funding remit is positive community engagement. The fab film, Leo The Last, was shot on Testerton Road, before this was demolished for the building of the Lancaster West Estate in the early 1970s. I'm trying to get the BFI to make a copy available for screening as part of my residency. A screening at the estate, followed by a project around housing issues, might be one possible form of engagement. Maybe I was due a quiet moment. At the V&A Museum we also find building works for a new gallery space. Kids are splashing about at the courtyard pool. Did I really hear one of my favourite Lee Scratch Perry / Max Romeo songs, Chase The Devil, emanating from the John Madeski Garden? Anyway, I met up with Martin Bastone who took me on a guided tour of the building. Fascinating to learn about its association with WW2 spies. I definitely want to visit the dome and see those panoramic views. Martin had previously assisted me in ensuring my studio was a safe place to work and hold workshops. I've been sketching in the Sacred Silver and Stained Glass Gallery. This is connecting me to Nathaniel Westlake (see previous blog), one of the leading stain glass artists of the 19th century. He had a house built for him a short stroll from where I am based in North Kensington. Also just around the corner is the historic Harrow Club. This was a former church, built in 1887 by Richard Norman Shaw, who is the subject of an exhibition at the Royal Academy. I'm planning on running a summer workshop at the Club evoking the history of the building and its current use as a vibrant community centre. This will involve local residents and children making "stain glass" images on OHP transparency film and for these to be placed on the windows of the building. The design might collate together stain glass and urban graphic art. There seems to be an interesting visual co-relation between these otherwise sacred and "profane" genres. I have also been working on some paper models for an architectural themed workshop. I've not worked in this format before, so it's doubly exciting to be able to share new skills and discoveries. There is a RIBA and V&A educational resource that I can dip into. I now need to think about building a panoramic installation for the display of these models. The garden space at the studio will suffice for the moment. On Saturday 2nd August, I have an Open Studio day. This is from 10-5pm at 7 Shalfleet Drive, W10 6UF. The studio is directly opposite Latimer Road tube station. I will have art on display and info about workshops to be held at the studio and V&A Museum. It would be great to meet more local residents and find out about their experiences. If you would like to visit, please R.S.V.P : [email protected]. I've finally signed my tenancy contract with RBKC and have kicked the studio flat into shape. It's been a busy week. This has involved disposing of the former resident's (mother and child) personal effects including abandoned toys. The poignant wall markings made to measure a child's growth still remain. Several licks of paint and Constantine's your uncle, the V&A Museum Community Artist. I am uniquely based at a former council flat that is part of a housing redevelopment. All the flats on this side of Shalfleet Drive will be demolished in about six months time. The tenants (apart from me) will all be rehoused in the new building. Needless to say, after a year of building works, they are really looking forward to this. I had a nice coffee chat with Linda and Ted Smith at No 13. Hoping to feature them in a film project.

The studio is a perfect space for me to work. I'm responding to the theme of housing and regeneration. The patio overlooks the building site although it feels as if the building site and the towering cranes are overlooking me. I've been out in the dusty and noisy garden making sketches of the trees surrounded by forklift trucks, pallets and busy workers. These trees will form the heart of the enclosed garden. They are the only surviving element of this section of the estate that included a nursery and garages. In the breeze, these trees might whisper to future tenants. Tell them the story of this area and its complex social history (pigs, pots, slum, race riots, squats). I recently had my first session at St Anne's Nursery, kindly assisted by Laura Southall who is looking after me at the V&A Museum. For 75 kids we made a time travelling drawing that introduced them to the Egyptian Pyamids, Greek Temples, Turkish Mosques, Big Ben, the V&A (also currently a building site) and houses in outer space. I'm looking forward to revisiting the school after summer to engage in large scale panoramic drawings. Steph Perkins is the estate liaison office who works with the building contractors. She is currently organising a poster hoarding competition for the perimeter of the building site. Tasneem Howard is a super talented, nine-year old who has designed one of the posters. At the Harrow club we have been assisting her. Her picture is about the club and the community facilities she enjoys there. Tasneem likes art, but wants to become a veterinary surgeon. Maybe she'll be an artistic vet. Speaking of grown-ups, my first session in the studio was with several friends who helped me produce a drawing about our personal experiences connected with housing. Steve Gross: "I'm thinking back to the house I grew up in with my mum and dad and sisters. The stairs were a very important thing. They'll all be watching the television and I'll be sent to bed at 9 o'clock. But I wouldn't go to bed. I'll sit at the top of the stairs and hear them laughing and laughing and laughing at Monty Python's Flying Circus. I couldn't see what was going on. I felt really excluded. It was very unfair. This incident is an amalgamation of several where I smashed the window and then they are coming to look for me and I'm hiding under the stairs (laughs) waiting for them to tell me off. I was about eight. There was always something up and down the stairs, or under the stairs. Caroline Stingmore: "There's a conflict. Because this picture is from my childhood. Really happy childhood memories growing up in Ireland. My dad had a rockery and he always put orange marigolds on it and we all hated them. But now we loved them, but at the time we hated them, they were so orange. My mum always provided wonderful heartwarming meals. That's a big memory. And the cherry blossom tree in the garden. I used to dance around it like a little fairy. It's all idyllic. And in this picture is where I felt very guilty when my boys were born. We were living in a council estate and I couldn't give them what I had. We were trapped in a flat in a high rise block. They were okay actually, but I felt immense guilt and sadness." Down at the V&A Museum I've been researching an architect and artist who helped shape the historic built environment of North (and South) Kensington. Future blogs and art will focus on John Francis Bentley and Nathaniel Hubert John Westlake. Bentley built an artists house for Westlake, just a stones throw from my studio. They collaborated on several churches, most noticeably St Francis of Assisi on Pottery Lane. It was great to meet some of the staff at the V&A. Martin Storey, curator in the Word and Image Department, has shown me architectural models and a fascinating sketch book by William Burges. Marisa who works on the Community Programme has suggested potential audiences for my work. Next week, I'm visiting Elizabeth Grant, Education Curator at RIBA and look forward to connecting with their resources. Over the coming weeks, I will be working up my detailed plans for community engagement. These include negotiating with the BFI about screening a seminal film (Leo The Last), running summer workshops for local residents, devising a combined cycling and drawing tour of the Royal Borough's most important and quirky buildings, and collaborating with local residents in the making of a film about the housing redevelopment. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed