|

Jordan Stone, film maker in conversation about his parents, Barbara and David Stone,

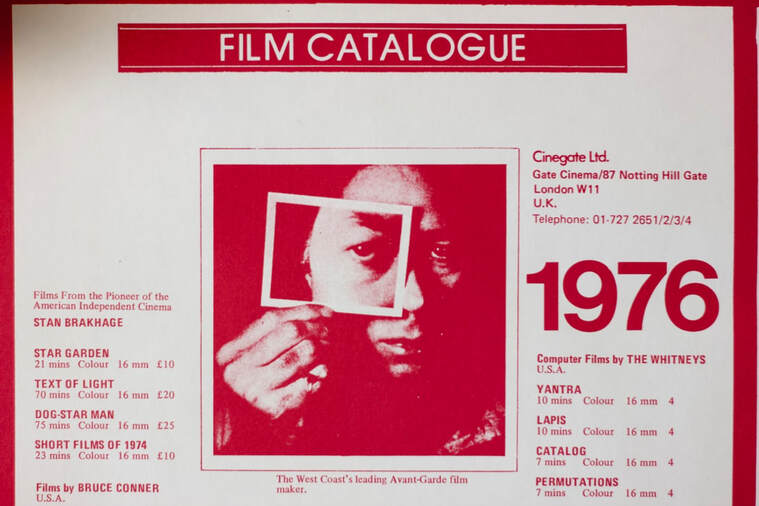

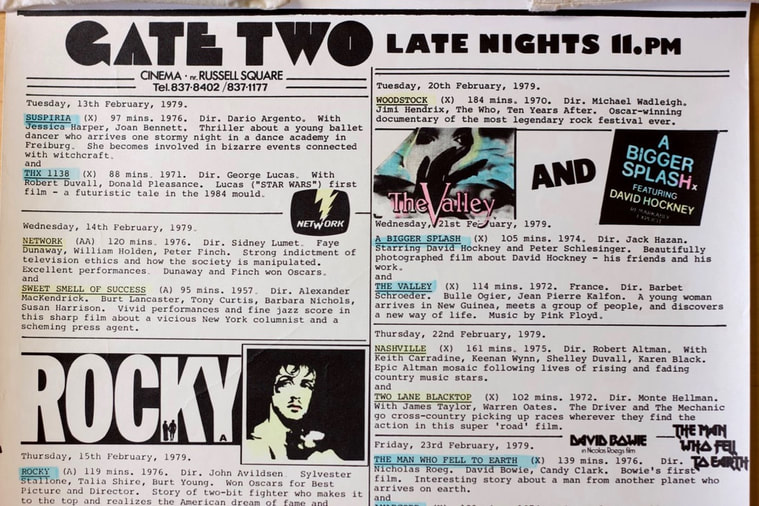

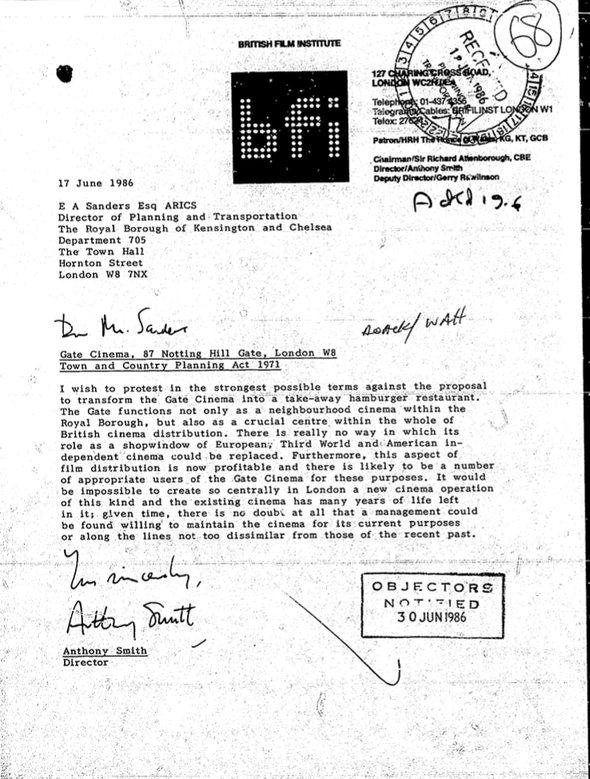

who opened a pioneering art house cinema in 1974 at the Gate, Notting Hill. The family moved to England in 1971. I think what my father originally wanted to do was to open a New York styled delicatessen in London where you could get bagels, cream cheese, smoke salmon, pastrami on rye bread. That was his original plan. But my parents had a passion for underground, avant-garde and independent cinema. They had been attending film festivals from the very early 1960s, whether it was Cannes or Venice. They were the creators of the Spoleto Film Festival in 1959. And so they were very familiar with European directors, the press, film critics, historians and writers. They had also been involved in the various film art movements in New York. They had made films themselves and also produced films with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. So at some point, they realised that there was this huge area that was missing in film exhibition and distribution. And that was their talent: to create a distribution and an outlet, a cinema, at the Gate in Notting Hill for showing these independent films. At that time films were still being dubbed for UK release. And there were films that would not have found a way out of their country of origin. My parents combined their passion with the business. But taste has to obviously come first. You have to create that and show it to the public. In America there is also a certain passive-aggressive approach to business whereas in England, it's a lot more passive. Maybe aggressive is not the right word, but they were more proactive, a term used today, but not used then. And so, it's like everything aligned at the right time. A cinema became available for them in Notting Hill. It was called the Classic. I think the previous owners couldn't afford to keep it going and that was the moment to strike as it were. What you have to realise is that the distribution company Cinegate and the Gate Cinema went together. What we distributed was what we showed. In the Cinegate catalogue, we had a huge collection of experimental cinema from Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Stan Brakage and the Mekas Brothers. And what also was remarkable were the late night double bills, mainly from other distributors, mostly American classic and cult films from the 1930s up to the 1970s. My parents created this culture of late night screenings that started at 11pm and went on till 2 or 3 in the morning. No one else was doing that. I still bump into people who tell me that they saw this film 25 times because they went to the late night program every other night. And unlike other cinemas, the Gate was open 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year including Christmas Day, New Year's Day. We were open every single day. Other cinemas started to copy us with late night programming. The Scala started doing the all-nighters at weekends. The Electric that was just down the road from us, on Portobello Road, was a repertory cinema. Peter Houghton who ran that cinema had perfect taste. It was an absolute fleapit at the time, but they created their own cult even before the Gate. But it was very different from our cinema. They would show a week of Hungarian movies and then ten days of German New Wave and then a week of Charlie Chaplin. And they showed a lot of films that we distributed that fitted perfectly into their programming. But they weren't opening movies. We were and they were independent, art house films. There is a nice little story. The Electric went through many periods of running out of money and my father insisted on lending them some. It was a real beautiful little moment unheard of that one cinema would help out another in the same area. I don't think my parents started up their operation thinking in a competitive way whatsoever as opposed to enhancing the whole concept of British Independent cinema. A few years later, once everything was going well, my parents had a good relationship with EMI and Barry Spikings, its head at the time. He had produced The Deer hunter and EMI had a cinema in Bloomsbury. But they had no idea what to do with it. They didn't know how to program it and so they gave it to my parents and the rent was completely reasonable. After a while, Gate Bloomsbury (now the Curzon Bloomsbury) was divided and had two screens. Then some short time after this, the same thing happened with Rank who had a cinema on Camden Road. My parents took that over and it became Gate 3. And finally, in the basement of a Mayfair hotel, there was this wonderful, tiny, super-exclusive cinema with just 40 or 50 seats. That became Gate Mayfair. When we first opened in Mayfair, this must have been about 1980, Mephisto, which was a huge success and went on to win Best Foreign Picture Academy Award, that was shown at Mayfair on a second run. I think it was playing for 9 months. My sister says it was shorter. But it felt longer. The majority of art house movies were definitely not American. The only American art house movies would be ones made by first time directors who sometimes had a distribution deal with a major company. And so the only way you would find out about these films was going to film festivals where the producers would be at Cannes, Venice or wherever they were trying to sell their films. My parents would be looking out for these types of films. Jonathan Demme was a Roger Corman protégé and his first couple of films we opened, I think we even distributed them. There was CB Radio and Melvin and Howard.

There were moments that brought great controversy that fed into the success and mythology of the Gate. Derek Jarman's first film, Sebastian, for example. The dialogue was in Latin and there were scenes of men making love to each other. It was definitely not pornographic, definitely an art film. But they were under a lot of pressure from the Board of Censors which was run by a guy called James Ferman, who was also an American. There wasn't much love between him and my parents. There were lines around the corner of the Gate Notting Hill because the only film prior to that which could be conceived of as a homosexual film was A Bigger Splash. That was a film about David Hockney and we ended up showing that at the late nights. But Jarman's film was a full-on feature film and made by someone we had never heard of. We had a lot of celebrities and famous people coming to see that film in 1976. And then a couple of years later with the Oshima film, In The Realm of the Senses, where you had two lovers making love throughout the film and in the end the girl cuts the man's penis off. That film was refused a rating by the Board of Censors. My parents came up with a way around this; which was to turn the cinema into a club. So people had to be 18 and pay a minimum 25p or 50 pence membership and then they could buy a ticket to see the film. But as kids growing up, we were told to stay away from the cinema because my parents were expecting to be raided by the Home Office every day. I also know that for that film to be seen, they put together a list of very well known people who had signed a petition demanding that this film be allowed to be shown to the general public. This was not just film people or from the entertainment industry, but also politicians.

The regeneration of Notting Hill had not happened at this time. That was much later. Everyone who was everyone was coming to the Gate. You had to imagine Harold Pinter living down the road and he would want to see everything. We had people who loved film and wanted to see films that the film critics were writing about and that would not otherwise have a chance in a lifetime of being released in its original form. We had punk musicians, artists and photographers, a lot of theatre people and of course, the general public.

My father was always charging a little bit more at our cinema. There was a reason for this because we were showing films exclusively. I think our first ticket price in 1974, for Fassbinder's Fear Eats The Soul that opened the cinema, was 60 pence; but after a year or two, this went up to 90 pence. And of course, we were an art-house. You were going to pay to see art. He wasn't trying to rip anyone off. It was a very exclusive approach however. And my father was actually quite short and the rows in the cinema were based on his leg- room. What he wanted to do was get as many seats in as possible. So we did have a reputation of having very thin rows, but that was based on the fact that he was quite short. I think we had 282 seats. If you look at the Gate today, my father would be surprised what it turned into with the sofas, the tables, the feeding and drinking during the film. I remember we were one of the first households that had a video projection system at home because film-makers from around the world were sending us films to watch. We grew up watching films that never made it into distribution. We had friends coming over to the house who never knew what a video was, VHS or Betamax. And we had equipment that was flown in from the states. This was set up in one of the rooms in the house, a screening room. Actually whether we lived in New York or London, my father always had a 8mm and 16mm projector set up in the house. Saturday night we would be watching films. They were very social events with film critics, Chris Petit, Nigel Andrews, David Robinson and filmmakers. We were also very friendly with someone who worked at the National Film Archives and every weekend he would come with a 16mm print under his arms, something that was 40 or 50 years old. My mother would do a big dinner and then we would all sit and watch the movie. That was a large part of the Stones' reputation. From the age of 11 or 12, I was working in the cinema and the Cinegate distribution dispatch office. Cleaning the films, packing them up and taking 16mm and 35mm prints to whoever was renting them. My brother and sister were also working with me in the cinema, making popcorn, tearing tickets and in the projection booths. I was also an actor and then at the age of 16, I had already started a video production company. Then a producer friend of ours asked if I wanted to be a runner on one of his films. That's how I started making my way up as an assistant director and have never stopped. I still am a first assistant director on feature films, commercials, and music videos. I was based in L.A. for a long time, too. And now I'm operating out of Italy. I look after a lot of the filmmakers who come to shoot here and I've turned that role into a type of service producer as well. I've produced projects with Sofia Coppola, Mike Figgis, Spike Lee. I’m a filmmaker myself. My films are not commercial and that is a result of most of my life working on other people's movies whom I've learnt so much from. The lesson that my parents ingrained in all of us is that you have to do what you feel is right - for you! And we grew up in an anti-commercial atmosphere. Anything that was American studio was the devil. We knew from the beginning that people who went to America to make films, compromised their creativity, because a producer or the studio said we want more tits and ass and more violence. However In the last 5-10 years in America, I've found that there has been a rush of films that are very independent. But most films can't be made unless they have a distribution deal. The film studios and media companies will put money into a film for its distribution rights. The filmmakers are not dictated to as badly if it’s a non-studio film because they have got the money just for distribution. So what's happened is that it's allowed much more of an independent approach to American filmmaking. There are many different structures to put a film together. You can raise money privately; you can raise money through pre-sales, through distribution sales, money from the studios, from several companies or countries. Tax incentives. It's a whole quagmire of things before you can get interest for the project. But if American studios are involved, the more control they have over the finished product. It's a different process for a European or a Chinese filmmaker. I saw a space to do commercially what my parents had done in London during the 1970s. I ended up for a while programming two cinemas in Milan in the same style as the Gate. I also created CinemaStone and this is not just a production service company, but it also dealt with film and event programming. I grew up doing what I was destined to do.

Barbara Stone Unpublished - trailer for film written and directed by Jordan and Veronica Stone

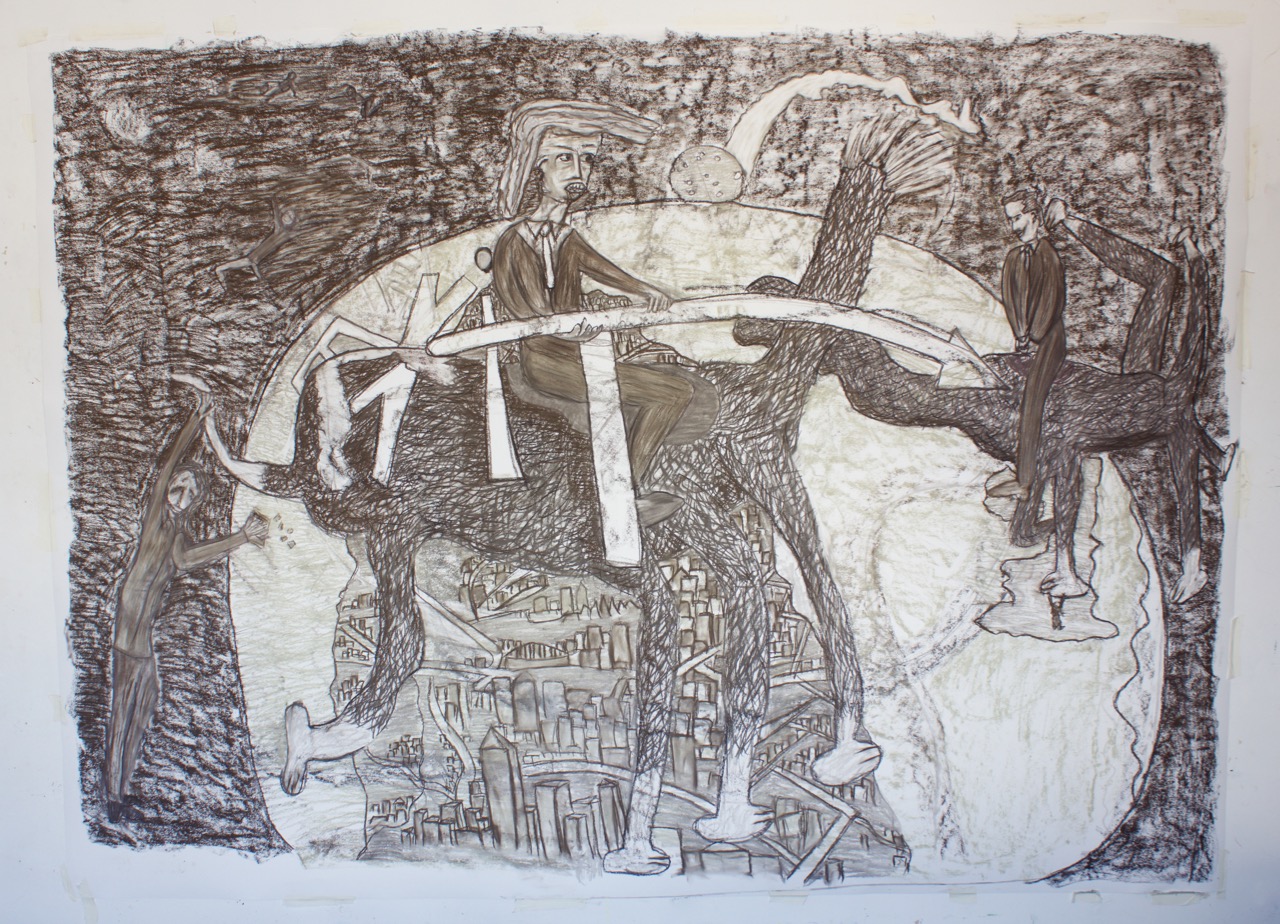

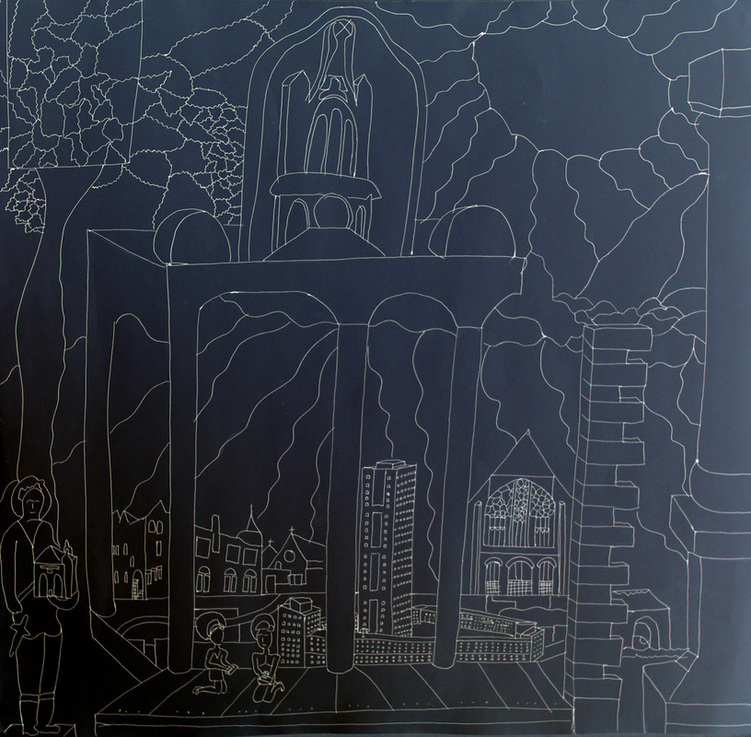

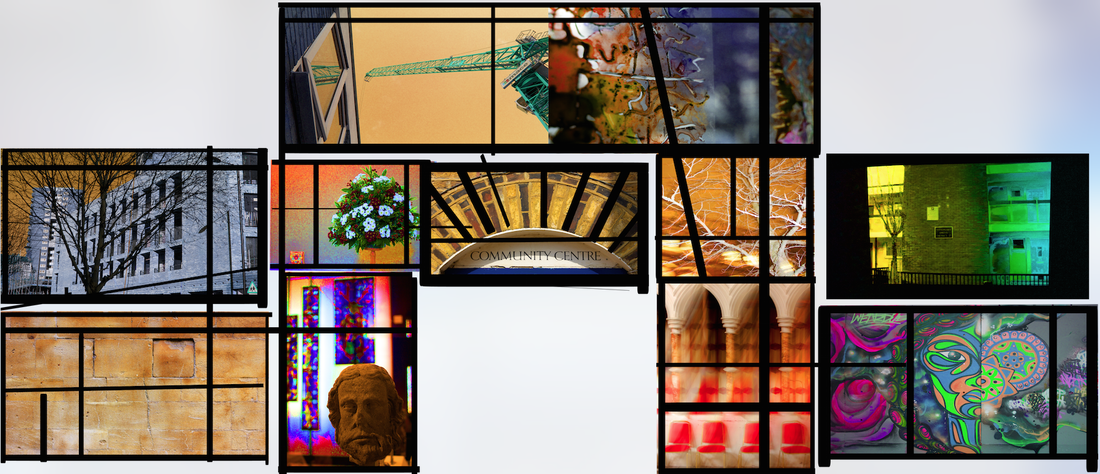

Jordan Stone's website Poster art work from the Barbara Stone Archive recently deposited at King's College, London And which will be available to view over the coming years Drawing by Constantine Gras: When a kiss fans out Watercolour, pencil, ink 9.5 x 12 inches, 1994 Link to film event called Emotion and Economics - A history of the Gate Cinema

2 Comments

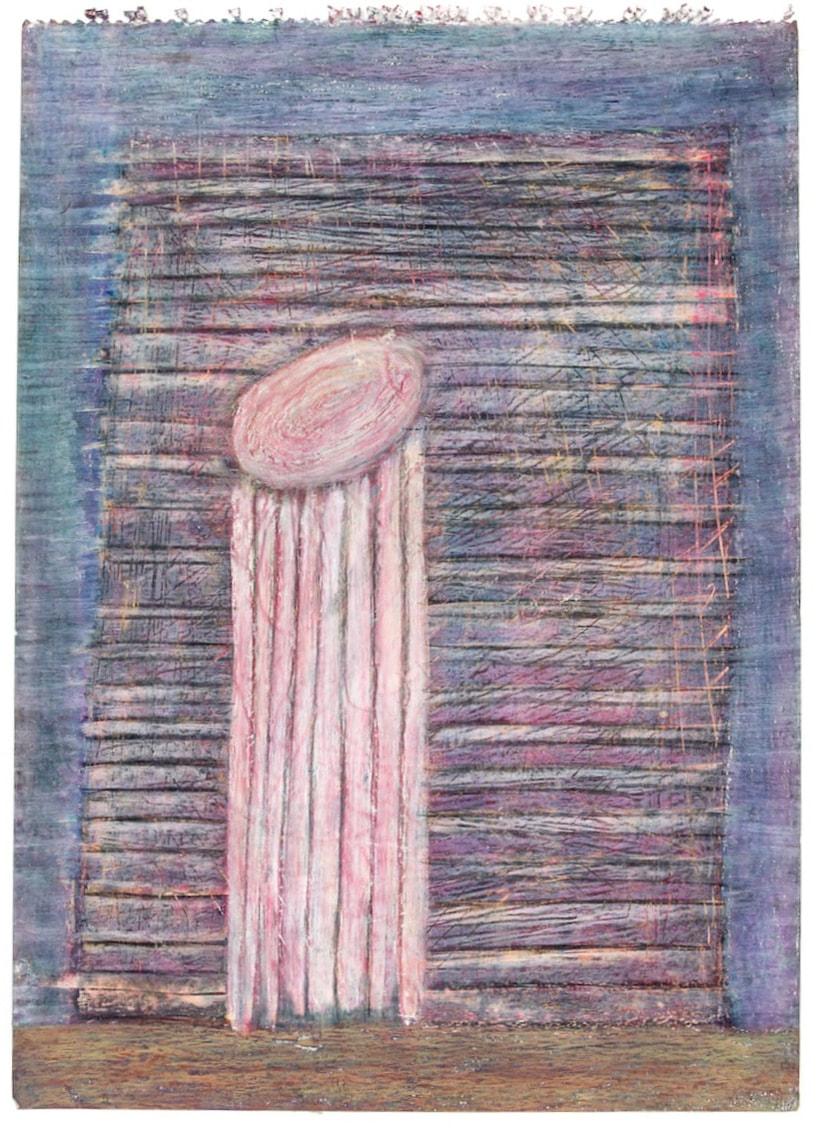

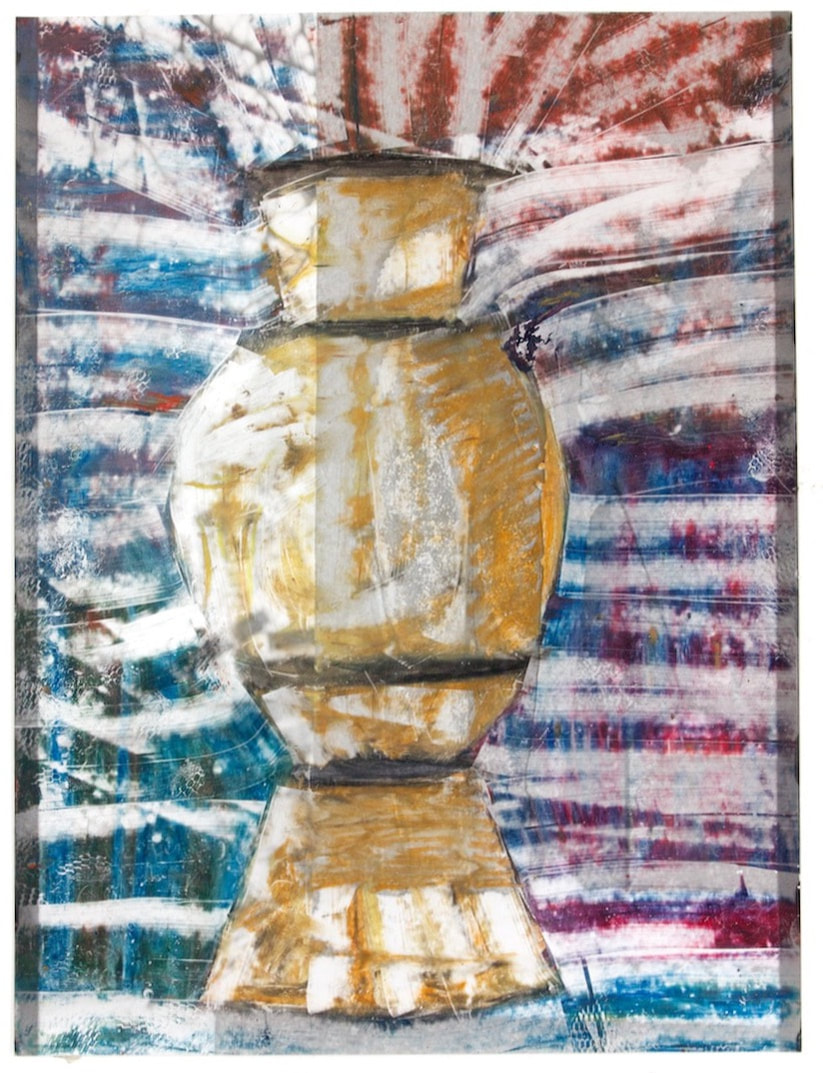

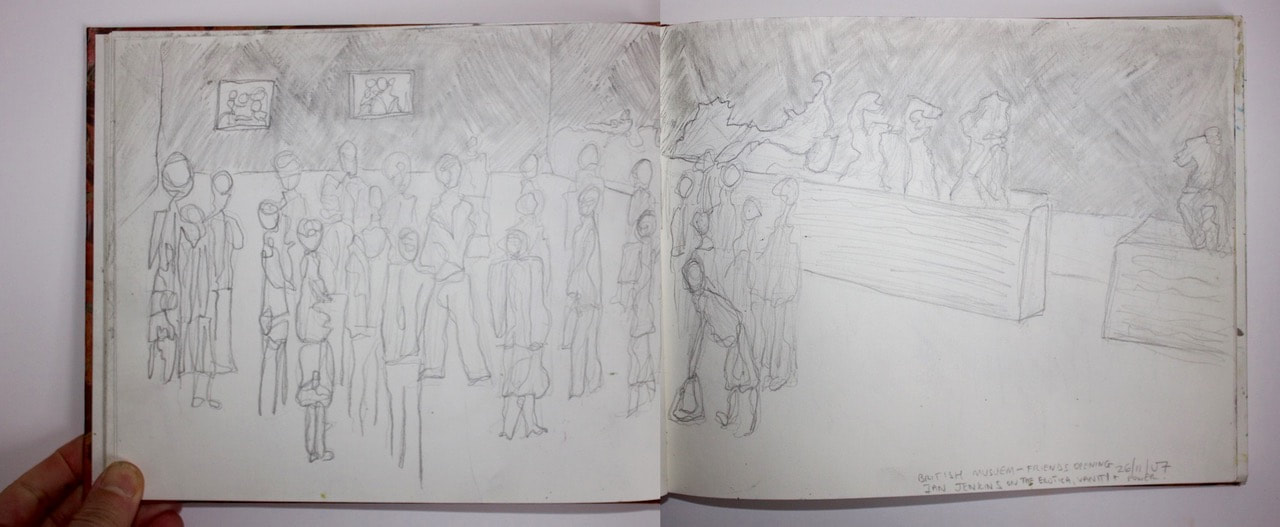

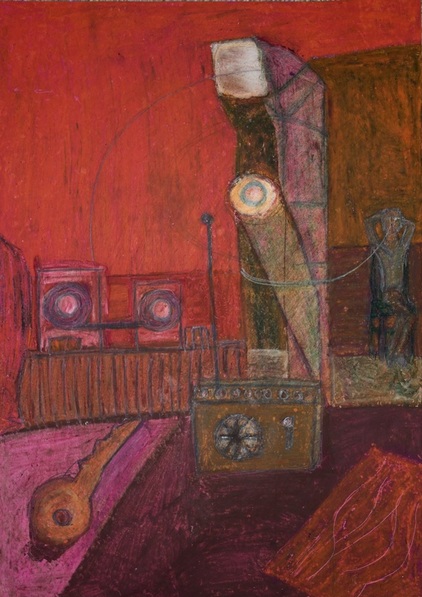

Unfurl a roll of paper to walk across the marsh grass fields of Kenilworth. This is a landscape that once had an artificial lake to defend the castle And where the longest siege in English history took place in 1266. The medieval scream of arrows is not conducted into my middle ear. But an image develops in the liquid memory. Bright young things, mustering arms, on the footbridge. A battle of poohsticks in the brook. Laughter resonates even at times of civil war. The paper curls back. Greek column at Willesden High School 2003, oil pastels, A3 Love vase for Jacqueline Augustine - Rice and peas and ackee! 2005, Acrylics, A3 War vase for Achillea Achillea - I'll kill ya, Achillea! 2005, Acrylics, A3 Visionary vase for Mr Cobb - Artist, Musician, History Teacher 2005, Acrylics and Oil Pastel, A3 British Museum, Friends Opening 26/11/07

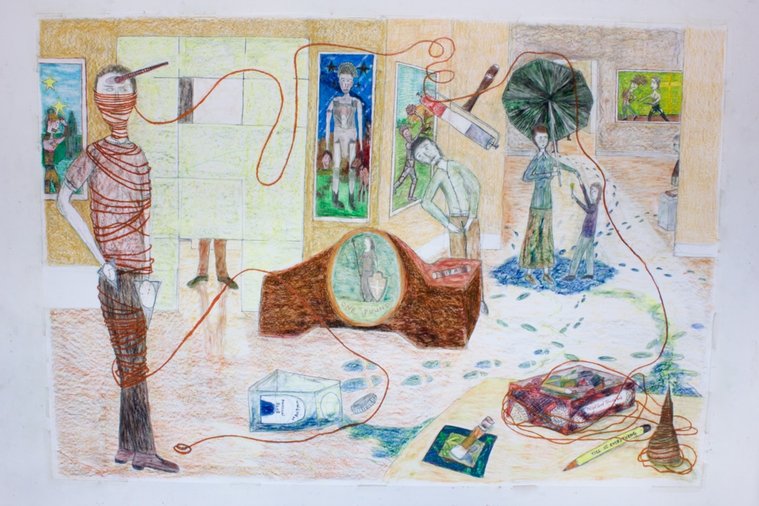

Ian Jenkins discusses the vanity, erotica and power of the Elgin Marbles 82 x 56 inches. Oil pastel, pencil. 2017. Poem to a drawing Are we walking down a corridor in the National Portrait gallery? Walls lined with the great and good who have killed and conquered. This is all rather tiring and I am looking for somewhere to sit. Commotion in a room ahead, left or right? A gust of wind blows us into the Euro wing. We see a mother and child with candle and umbrella. A man checks his flies are zipped. Above his head, a tricolour ink roller in suspended animation. On the ground, footprints of Prussian blue. Centre stage, chaise lounge. What is going on? Can we sit here? Maybe in the next room, next to a woman and her copy of J. G. Ballard's The Atrocity Exhibition. In front of a painting of the British Prime Minister getting fruity with the American President. Hold on! Is that Robert Rauschenberg trapped in twine from a plumb bob? He appears to be pointing backwards and forward, one hand to 1974, the other, 2019. Can we trust an artist to TELL US EVERYTHING about this space within space That has spilled out from a box labelled Highland Shortbread? Where can I sit? My legs are killing me. Notes to myself This was sketched immediately after visiting the excellent Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at Tate Modern and during the United Kingdom government's formal notification of withdrawal from the European Union. This was also the week when The Daily Mail newspaper on March 28th featured a photo of Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon with the trivialising head line: “Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!”. On the same day, a new 12-sided £1 coin became legal tender across the UK. Pondering all these matters, I started to sketch a scene using Robert Rauschenberg as an enigmatic muse. His free and easy approach to materials, for example, building an umbrella or fan into a painted surface, had me thinking about how to use everyday objects as part of my art practice. I turned to a biscuit tin in my studio. I don't know why I started to collect objects in a biscuit tin or how long they have accumulated (more than a decade now), but this box with random objects ranging from coins, fuses, tea coaster, plumb bob, pencil emblazoned with "Tell me everything," was raided for inspiration and incorporated into the drawing. This was my equivalent to Rauschenberg's "combine" although I have made no concession to three dimensionality. There is added irony in that the box has a culinary connection with Scotland; a nation destined to have a falling out with the English over the issue of falling out of Europe. All these objects and related ideas came tumbling out of the box and into the composition. Some other allusions for the cultural critic to register:

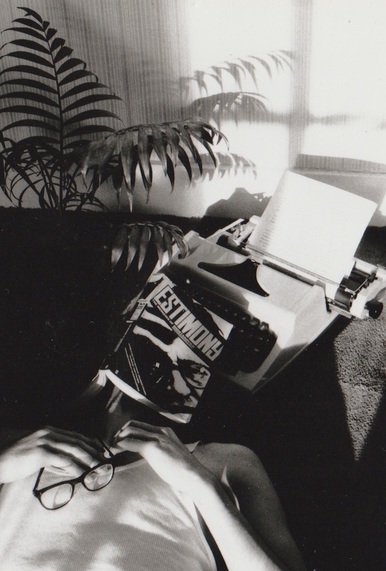

A New World Order Pastel drawing, 60x81", 2016 The Grand Christmas Comic Pantomine At the mythic Elephant and Castle Theatre Boxing Day, December 26th, 1876 Entitled Trump and Farage; Or Harlequin Progress And the Knight that fought and gained the day Characters Donnie Trump ------- performed by Miss Marie Henderson A powerful and scheming knight in love with Nigella and himself Nigella Farage ------- performed by Mr Walter Grisdale Mistress from Ing - Land who whip lashes her Euro body politic Hilaricious Clinton ------- performed by Miss Clara Griffith Deposed Queen trapped in the world wide web Theresa Maypole ------ performed by Mr Watty Bruton The titular head of state who is forever Brexiting, stage right. A production on a grand scale with thrilling scenes: Donnie and Nigella riding the headless horse of the apocalypse; Hilaricious hanging onto the tale of the headless horse; And Theresa, trying to exit stage right, but being trampled under horse hoof. All told, a magical transformation. This new world order has to be seen to be believed! Trump and Farage has been expressly sketched for this theatre by Constance Graf. Stage notes: 1. Pantomine is a type of musical comedy performed in the United Kingdom, generally during the Christmas festive period. It has gender-bending roles and a story loosely based on a fairy or folk tale. 2. Henderson, Griffith, Grisdale and Bruton formed the cast of the Elephant and Castle Theatre company in London between 1875-1880. Marie Henderson was also the directress of the company. 3. If you want to sample a pantomime, here is a link to Valentine and Orson. This text was written in 1877 by Charles Merion and is his third adaption of the medieval romance tale about twin brothers abandoned at birth, one raised in the royal court and the other in the woods. Another version was the first play performed at the Elephant and Castle Theatre when that was opened for business in 1872. The theatre building is now the Coronet Club and this is due for demolition in early 2018 as part of the regeneration of the Elephant and Castle area. What would you do? Imagine your neighbour Heinrich Boll had left you a spare key and instruction to water the house plants while he boarded an aeroplane to collect a Nobel prize. Would you steal inspiration from the draft in his typewriter? Or Max Opuls had entrusted you, his dear friend, to retrieve a roll of film from his house; the one the censors didn't see in La Ronde. Would you leer at the said negative being held up to a bright light source? Kathe Kollwitz had to nip out to buy some milk and bread. Mischievous thought of adding a smiley face of ink to the desolate image in the printing press? The aforesaid fantasies were inspired after listening to an interview Holgar Czukay gave in the early 1990s on the Radio 3 programme, Mixing It. He recounted how as a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1968, he sweet talked the secretary and gained access to Herr Aladdin's electronic cave. Holgar was able to record his debut album, Canaxis 5, with the studios impressive tape recorders looping together his interest in Musique Concrete and ethnographic folk recordings. Not all studios live up to their profession. In point of fact, given the relative poverty of artists, they invariably have to beg a shed, borrow a broom cupboard or steal a loft. I have only had one bonafide studio. This was once a 1960s council flat (bedroom, living room and a kitchen) and came with the responsibility to practice community art. An author might build a studio around the typewriter on an heir loomed desk or a poet might dream on a hammock in the garden. Maybe virtual studios will one day be the norm for web based artists. The creation of an avatar, perhaps even adopting the identity of the Germanic artists I have already listed. Expanding on this chain of thought -what about that elusive key to the artist's mind?

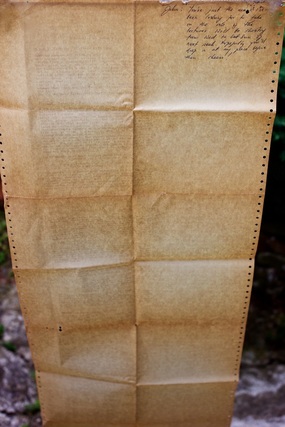

Script for This-That by Jacob Barua. Printed on continuous feed paper, Warwick University science block.

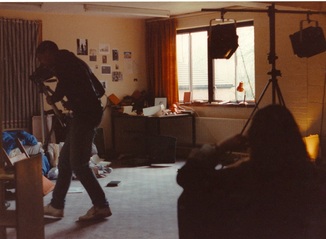

I am navigating back to 1989 and the University of Warwick. My fellow Film and Literature student, Jacob Barua, has handed me a film script and declared emphatically: you are the only person in the universe who can play this! I hesitated. Had never acted before. And then there was the troubled central character in the drama who seemed all too recognisable; forever on the edge of everything, nothing, relationships, art, politics. This begged the following question: Jacob are you taking the piss out of me or yourself? For a short period of time we seemed to swap identities. Jacob’s intense cinematic vision became one with my suited and booted persona. Jacob was going to use this short film to catapult him into the prestigious Lodz film school. But it was no plain sailing. No film production on this dramatic scale had been undertaken at the university where theory ruled the day. It meant sniffing out equipment and resources. After two weeks of filming, a mere two days were spend in the edit suite, using equipment for the very first time. I recall a few expletives. We had set the date of screening, one day after the final day of editing. A key animation sequence shot on 8 mm film only arrived on the day of the screening and had to be added post-haste, post end-credits. Thankfully this has now been re-edited into its proper place in the dreaming body of the film. We finally have the keys to the digital edit suite. It's only now after 26 years and working together again on restoring the fading VHS tapes, that we’ve got a new grasp on the importance of this film for us. Let me leave the final words to Jacob Baura who was recently interviewed about his Warwick experience. What on heaven or hell was he thinking about when he made This-That?

Jacob Barua:

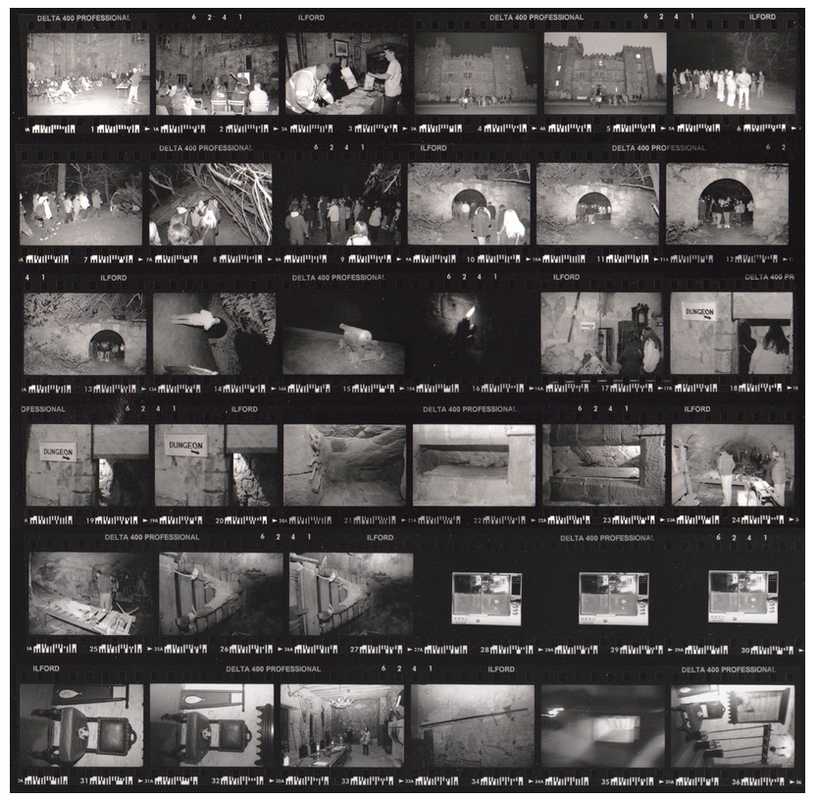

"The reason I wanted to become a filmmaker, did not have that much to do with film per se. I had always been enthralled by Art itself in all it's aspects. I had been a poet, a musician, a painter, photographer, amateur actor, but probably loved literature most of all. Somewhat like a brat with his hand in a jar full of goodies, I did not want to let go of any of the Arts and decided that there was was only one vessel that encompassed all of them. The only way, in which I did not have to discard any, but instead fuse them, was through the glowing medium of film. I arrived in Warwick...by mistake. One of my obsessions when it comes to the written word is History. Right until today I often wonder whether I am a self made historian expressing myself and researching through film. Warwick conjured in my mind the mystery and glory of medieval times. I was convinced that the University of Warwick was located somewhere within the town of Warwick. In those pre-internet days, a major source of information were brochures. And the university's were filled with images of Warwick Castle and the old cobble stone streets. That was enough for me to decide, given that it was simultaneously the only university offering such a broad course encompassing foremost literature and then film. I got off the train in the quaint railway station only to be horrifyingly informed that the university was far away in some fields between Coventry, Leamington Spa and Kenilworth! I found the course at the university to be exhilirating in it's scope - exactly tailored to my needs. Great lecturers and given the small size of our department, an opportunity to bond with colleagues. The university also happened to probably have the largest independent Art Centre outside London, at the time. There was everything ranging from a philharmonic orchestra to to a cinema with plush seats and a sterling screen, to one of the best equipped professional theaters anywhere in England. Here I was active as a member of the Warwick Drama Society, taking on delicious roles for the duration of my studies. Besides, the university was a beehive of political activity, of all manner of shades. Of course I was aghast that the most prominent ones were for naive fellow travellers of all manner of totalitarian off shots. However the jewel of this mini-city was a massive library, with a salivating wealth of books that was beyond belief. This-That was the result of a deep inner need to encompass my entire experience as a student who had lived in different countries, cultural and political systems. At the same time I set to creating a time capsule to be sent into the future. All Myths were after all created by somebody, even if that was thousands of years back - so why not make one too, there and then, to be flung into an unfathomable distance? My inspiration for the main character was essential to creating a core, and this was based, at least in terms of the visuals on a readily available 'blueprint'. For I used Warwick's most enigmatic and unique real life student - Constantine Gras. He did not fit into any preconception - as he neither had the persona of a typical student, nor even one from any 'civilian' from our contemporary milieu. Here was Someone who seemed to have been historically misplaced, from a 'wrong' age. Like a potter I used him as my clay, to impose onto him a narrative, which I knew would jar when combined with his persona. So here was a man creating himself i.e. Constantine, whom in turn I was creating further. Layers of creation. One of the overarching themes is the struggle that each human has to undertake to find a space of comfort, to be able to be oneself, while struggling against the dominant societal forces. By comfort I do not at all refer to a personal one, but that of the Other. For the most crucial single question ever spoken for me, which forever thunders across all ages is; "Am I my brother's keeper?" We live in a world circumscribed by political correctness. The moment you challenge the narrative of the day, you are deemed fit for condemnation and rejection. In the case of the film, the character not only isn't ascribing to Modernity and the race to keep up with fashions both external and internal, but occupies a realm that defies the obligatory 'standards'. He is still both a reflection of the Ancient, Romantic and Future ages. Whether we like it or not from the beginnings of History, politics impinge on almost everything in life. That is why the culmination of the film is congealed within the incongruous figure of a young pyjama clad student who dares to take on the Rulers of the World. The selfish manipulators - the Daeduluses vs the selfless dreamers - the Icuruses. If I were to try to draw a circle; Sleep - Pyjama - Dream - the Impossible - Courage - Death - Eternity - Sleep.

The reception of the film, I will admit, was heart breaking. An outright regurgitating by the audience. Particularly so - when not even our lecturers or collegues could grasp or extract any meaning out of it. But this should have been expected, as it was intentionally put together in such a way as to defy conventional modes of film-making. And again, it was indeed a film made for Another age. But which one? Time will still tell.

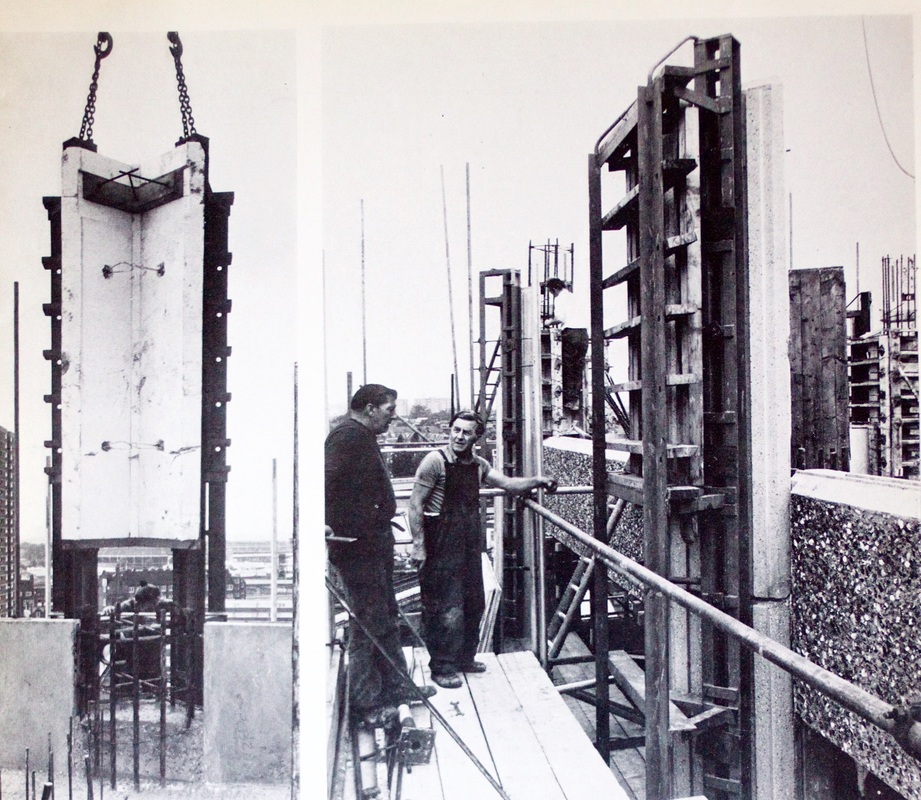

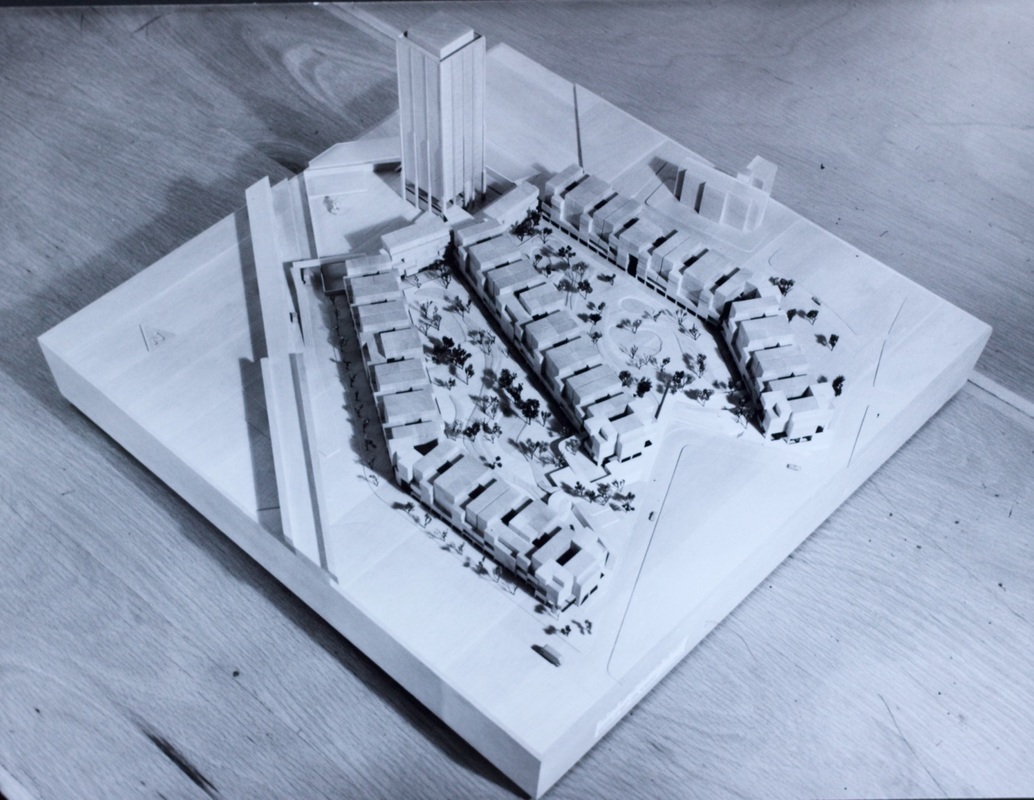

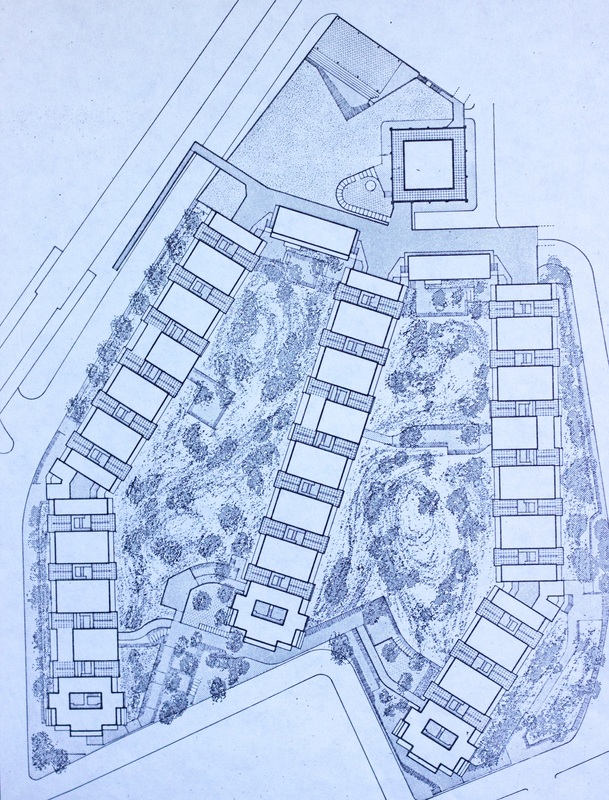

I have no regrets about the film as it was then, and in it's curent slightly re-edited form. It turned out prescient. You are Alone among people. To be fulfilled you have to metaphorically fly, even if demise is the price to be paid. There is no escaping Newton's and other more serious Laws. But just like there was no relevant message in the film for the audience at the time, there similarly isn't any for those today. There are plenty of other better sources, dear audience member, if you are in need of a message. This is not a cerebral feast but mainly a sensory experience. Once I got there, one of the most satisfying experiences at the Lodz Film School was when all students were herded into a cinema, and made to watch the film by Piotr Wojciechowski; he was a Filmmaker, Scriptwriter, Catholic Philosopher but most of all a living legend as a novel writer ("Skull within a skull", "Is it worth to have a Soul" and others). He immediately took to the film. In his laudatory lecture after the film, he said he felt it had the feel of T.S. Elliot's " The Waste Land". He was the first ever viewer to fully comprehend the ambitions of this film. At the Lodz Film School I carried on with the 'tradition' of making This-Thatian films. With no pretence at all. Poland's greatest ever fimmaker, and it's Chancellor Wojciech Has, would always chide other lecturers for being baffled by my films - telling them that they were wrong to search for conventional meanings in my short films. For him they were "Intricate riddles" I don't really have any wise tips for aspiring filmmakers. Rather warnings, in that it is going to be a lonely, cruel, and ungrateful journey, except for the very, very lucky few. Well, take heart - at least there's going to be one worthwhile viewer of your creation - Yourself. Having been trained on 35mm makes a filmmaker by far more disciplined and honed to the workings of a film. The Digital Age has its own advantages. But the downsides are greater. More self indulgence and turning an important medium of Art into a toy. I have been a gardener for a long time now. There's at least one massive film within me waiting to happen. Then I intend to go back to my gardening. It's this and that, after all." If you want to experience This-That, the film is screening on: 10th September 2016 around 7.30pm Muse Gallery, 269 Portobello Road, W11, London Portobello Film Festival Full venue and programme details. This-That Trailer from Constantine Gras on Vimeo. It is with great sadness that I have just received news of the recent passing away of Victor F Perkins. He co-founded the film department at Warwick in 1978 and made a decisive contribution to the acceptance of film as an art form worthy of deep study. I have fond memories of him hunched over the Steenbeck undertaking a close textual analysis of In A Lonely Place with 2-3 students; a more kinetic Victor was found over at the Student Union playing his favourite pinball machine; delivering those impassioned lectures where he poured his intelligence into the vessel of a film; seeing so much nuance in terms of decor and edit, so much so, that I seem to recall, at the end of one lecture, Jacob asked: is it really possible that the film maker meant all this? Victor bough a copy of This-That in 1989 for the university archive. It was always a pleasure to meet up with him over the decades since I graduated. Alas he missed the screening of the remastered film at the university in March 2016, but I was touched when he specially came in to see me and we had a good chin wag about life: how he was adjusting after a recent stroke, his desire to learn the German language, his concern about the corporate development of education and his cluttered honorary office in the department which he really should tidy up. I told him that we had dedicated the film to our old lecturers who had inspired the young to fly. Victor had a rueful smile. I've been working on Lancaster West estate for well over a year now. My commitment extended beyond the commission I had from the TMO (who manage the Royal Borough's housing stock) to make a mural for the new community room and a short film documenting the regeneration of Grenfell Tower. At the beginning, I was naturally regarded with a degree of skepticism. Why do we need an artist on the estate? But after attending numerous residents meetings and putting on art events in lift lobbies and during fun days, I earned my stripes in the community. During my tenure, I've had an opportunity to strike up many friendships across the estate. I offered them an accessible and sociable art. In return, several of them have entrusted me to render their remarkable life-affirming experiences and energising humour. More of these residents to follow. But first let's talk about regeneration and architecture and conclude by weaving both of these back into the beating heart and soul of Lancaster West. As of writing, Grenfell Tower improvement works is well nigh complete. After a £10 million regeneration, nine new flats have been created and offer affordable rents in an area where property prices average over £1 million and one bedroom flats on nearby More West are over £500,000. Each flat in Grenfell has had double glazing installed and a boiler for direct control of heating and hot water. The building has been thermally insulated with a new layer of cladding, although I miss the former design. The nursery and Dale boxing club also come back into vastly improved spaces and facilities. This upgrade to the fabric of a building is important in the context of how the council plan to regenerate this part of North Kensington. Silchester Estate, which is just across the road from Lancaster West, is currently being considered for regeneration. The initial options produced by the council were described as "nuclear" by estate residents. At a recent meeting in the town hall, several residents had the opportunity of making powerful statements to the council about the lack of consultation and the potential impacts of wholesale regeneration on the community and environment. The council listened and voted to explore the options in more detail. They also make a commitment to factor in the possibility of maintenance and infill. It is good to see how local residents are campaigning with a witty strap line (Gradual Change - In Due Course) that might have been culled from the insight of a former architect of Lancaster West, Derek Latham. He developed his ethos of urban renewal on a gradual basis after witnessing the impact of "slum clearance" in North Kensington during the 1960s and 70s. Previous blogs have featured interviews with Derek Latham and Peter Deakins, both of whom worked on the early stage design of Lancaster West estate. I can now present a complete documentary record of all the architects involved and their experiences, hopes and frustrations. One major issue was why the estate was never designed to its initial masterplan. This sense of fragmentation is perhaps the root cause for many of the challenges still being faced on the estate and which are being addressed by the newly formed Lancaster West Resident Association and the Grenfell Compact. I recently had the pleasure of meeting retired architect Nigel Whitbread and showed him around the estate. He lead the team who designed and built Grenfell Tower. It was the first time in over 40 years that he stepped foot inside the tower and enjoyed visiting a residents flat and those stunning views. What's interesting about Nigel's story is that he is a local boy through and through and not many local people seem to be aware of his role in the development of the area. We are also going to hear from Ken Price about the design of the finger blocks, the three low rise housing units that radiate out from Grenfell tower. Clifford Wearden is the design godfather of Lancaster West estate. I suspect his career path was adversely affected by the way the development panned out and not being the consultant responsible for all the later, much revised, stages. Chatting to his widow, Pauline Wearden, I was surprised to learn that, Clifford, like most other architects involved in the project disliked tower blocks. Grenfell tower was only included to maximise housing density levels; Nigel is an exception to this prickly high rise rule of thumb. This perhaps explains why Clifford in later life would drive over the elevated Westway and look across at the five tower blocks and declaim to his family that Grenfell tower exists no more and has been demolished for a new development. This is a poignant case of not wanting to see the concrete from the stone! Nigel Whitbread: I was born in Kenton near Harrow. My parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington. We moved as a family to this area in 1949 to be nearer the shop. I read quite recently Alan Johnson’s biography, This Boy. He is a Labour MP and former Home Secretary and interestingly was born in 1949. However his life and the poverty he lived through was in a different world, although just a mile away as the crow flies. He didn’t enjoy the family life that I enjoyed nor did he appear to enjoy his time at Sloane grammar school which I had done earlier. When I was going to leave Sloane, I didn’t know what I was going to do. One day I had an interview at an architect’s office. My eyes were opened. I liked the idea of drawing boards and doing something that I never understood to exist. The first firm that I worked for was Clifford Tee and Gale and that’s where I did my apprenticeship. I went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this I became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. I knew through delivering groceries that there was an architect who lived near my father’s shop. I told my parents this and my mother said she would speak to the wife of the architect who was also a partner in the practice. I went for an interview and got the job. This was at Douglas Stephen and Partners and this was probably the most influential time in my career. It was only a small practice but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that I worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. It was actually like going to a club and we were doing terrific work. Later on, I went to work with Clifford Wearden on Lancaster West. At that time his office was a two storey building in his back garden. It was a huge job for a small group. It was unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. Clifford was a serious architect but had a flair about him. He’d been in the Fleet Air Arm and had a lovely Alvis car which was a convertible as I recall. He did have a very bad habit whilst he was driving of turning his head and facing me whenever he was speaking which I always felt a bit disarming. I found this quirkiness an attractive aspect in somebody who was very precise in most things he did. The whole scheme had been well prepared and thought out by the time I joined to lead the team in designing the tower. The design is a very simple and straightforward concept. You have a central core containing the lift, staircase and the vertical risers for the services and then you have external perimeter columns. The services are connected to the central boiler and pump which powered the whole development and this is located in the basement of the tower block. This basement is about 4 meters deep and in addition has 2 meters of concrete at its base. This foundation holds up the tower block and in situ concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams all tie the building together. Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968, had been built like a pack of cards. Grenfell tower was a totally different form of construction and from what I can see could last another 100 years. Grenfell tower is a flexible building although designed for flats. You could take away all those internal partitions and open it up if that’s what you wanted to do in the future, This was unusual in terms of residential tower blocks. I also don’t know of any other council built tower block in London or anywhere else in England that also has the central core and six flats per floor rather than four flats which is typically done on the London County Council or Greater London Council plans. We were wanting to put our own identity on this. The GLC built Silchester estate and I had nothing against that but this was so different in many ways. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, we thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. We used insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, lifted up and put into place with cranes and they were so much more quicker. In an architects mind, they want towers to be an elegant form rather than stumpy. This was a challenge and was why I introduced as many vertical elements within the fenestration as I could. The only thing I could play with was the windows and the infill between the windows. I treated it like a curtain wall, to get the rhythm of a curtain wall. We lost some of this verticality in the recent re-cladding but it’s not the end of the world. And the building is now better insulated as we had different standards then. The floor plans were based on Parker Morris Standards which they used at that time and sadly have gone now. These were very good standards for storage and the way furniture had to be included in the plans. It was delightful to hear that residents thought flat arrangements worked well and I saw the views recently which I always thought were terrific. I wouldn’t have minded living in a tower block myself. Tower blocks were criticized for not being suited to people or a lot of families were being forced into it and they were feeling more and more remote from the street and meeting other people. But there is another side to this and it always seemed to me that if American’s can live in tower blocks, why can’t the English? This is the first and only tower block I designed. This was also the first social housing I ever worked on. No social housing has been built since this and I’m very much against knocking things down unnecessarily. I had heard that there had been problems a few years ago with the heating and it was no good and talk of the whole block having to come down. And I thought, if my heating goes wrong, I don’t want to pull my house down. It’s a great shame that the basic concept for the whole of Lancaster West to have a first floor deck for people, shops and offices and parking underneath wasn’t seen through for whatever reason. This means that there remains a basic flaw. Clifford Wearden and Associates only built Stage 1 and the remaining parts were built by other architects. I don’t think the designers are to blame because there was a requirement that it was designed to have cars for every flat. We’ve all seen things have changed dramatically since then and now cars can’t be accommodated everywhere. After Clifford Wearden, I worked for Aukett Associates and I was there for 30 years until retirement. Recently I’ve become involved with my local residents association and committees in drawing up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan. We included the Imperial West site over in Hammersmith and Fulham because that was already impacting on our conservation area. Hammersmith wouldn’t agree to this but we continued developing the plans liasing with RBKC and residents. The Neighbourhood Plan includes objectives around shopping, housing, offices and conservation. We have also identified 3 existing unbuilt spaces which are now designated as local green space and cannot be built on. Latimer Road is included in the plan and we think that could be redeveloped to improve the area and have more housing put on top of the business units. We have to have housing somewhere. That’s where you could do it. But don’t build on our green spaces. The Localism Act which the Conservative government introduced is a very powerful tool actually. Residents are able to influence the way their area is developed. Ken Price was lead architect responsible for the team who designed and built the finger block units (Testerton, Barandon and Hurstway) which formed stage 1 of the building project. Ken Price: My origins are in Derby in the Midlands. I went to the School of Architecture in Nottingham which at that that time was part of the college of art and is now part of the university. I worked for a short time in Derby and then I was offered a job to work in North Africa in Tunisia. I went there for 3-4 years. I came back and worked in Nottingham for a while with some ex-students who had set up practice there and and then changed jobs in and around London. After Lancaster West, I worked with Casson Conder partnership and was job architect on the Ismaili Centre in South Kensington. Subsequently I set up my on my own and did small scale projects, mostly interior work and retired a few years ago. Clifford Wearden won the Lancaster Road West development in Kensington. After a bit of a hiatus, the commission was confirmed for what was called stage one and he asked me to go and lead the team as project architect for the finger blocks. I worked for him and Kensington and Chelsea to develop the original masterplan which predecessors had worked on. Clifford was extremely good at handing over and saying - look this is the problem, you solve it and refer to me if there is still a problem. He was very generous although he had the overall view and concept. I know that he was very sad that the development became a little bit like the Barbican. It was a grander scheme and there could well have been more productive elements which just didn’t arise. I wasn't involved in those preliminary stages of development, so I can’t speak too much about how that evolved. But I was aware that the Silchester Baths on the site became listed and affected the masterplan. I briefly saw the housing in the area before or after it was all painted white because there was the famous or infamous film, Leo the Last. Was it black or white? Why did I think it was painted white. The director was John Boorman. I think I must have seen it just before they did that and probably immediately after. After it was cleared there was no real evidence of life or to how it was. I don’t even know what the state of the dwellings were like and whether they were totally without facilities. At that time there were a number of schemes underway to deal with the housing issue, alongside the problem of car ownership .One could describe it as the deck system when cars were kept down below and freeing up the ground level or the raised ground level for pedestrian use and housing. It was part of the brief to provide that amount of parking and it did subsidise some of the other elements. My predecessor had sketched in a basic outline of the finger blocks. I took that on and developed up the detail of the individual housing units and the spaces between. I suppose we were interested in the intricacies of locking together volumes of accommodation in order to maximise the space of each dwelling. Also providing, to a degree, some private outside balcony or roof terrace on the top areas so there was an opportunity for people to have their own little bit of outside space as well as the bigger outside. I still have a small model of the finger block that was made by a friend of mine, a model maker. It shows the different accommodation elements by colouring. It was really a demonstration to the council on the mix of the different elements. Community garden between Barandon and Testerton Walk. A constant source of artistic inspiration for Constantine Gras and featuring as the backdrop for several of his films: Vision of Paradise. The landscaping was dealt with by Michael Brown (landscape architect, 1923-1996). Clifford was very determined to ensure that the landscape was taken on and he persuaded RBKC to employ him. I think one of the essential elements in the concept was this endeavour to provide as much open green space as possible by concentrating the housing units. The density was probably what was expected or required by local authorities at that time. The estate was designed to try and retain that as much as possible and the tower blocks were an element in that because you’ve got a concentrated stacking of accommodation which again added to the freeing up of groundscape. Although there were a number of tower blocks around at Silchester I don’t think any of us would have chosen to have incorporated the tower block but it must have contributed to this density issue and freed up the amount of green space that was enabled. I think the estate was built to a good standard. We persuaded a brick manufacturer called Ockley to make bricks especially for the estate which weren’t available. It was just at the start of the introduction of metrication and it seemed to me, in particular, that it would be rather nice to make life easier in measurement terms to have bricks that fitted the metric. So they are specially made, 30 centimetre long bricks. We wanted to use brick as the main element in order to connect perhaps with the past more than you would have done with clip on panels. It does survive time rather better than a lot of materials. I still imagine they look pretty good. They were very nice brick manufacturers. I knew there was a hiccup in the construction process but I couldn’t quite remember what it was. (The contractor, A.E.Symns went into receivership in 1975 at the very end of the construction of phase one). I can’t think of a building site where that didn’t arise especially as the construction was over such a long period. There were industrial dispute problems (three day working week and building strike), but not hugely disruptive as far as I can remember. In those days it was very difficult to get contractors to keep the site clean. Now because of health and safety issues, I think building sites are much better managed. It’s a shame they never built the planned shopping centre or offices. There was an expectation of community facilities including commerce and everything else in order to make the place work. I don’t think there were any warnings flagged up that there might be vandalism. It certainly wasn’t in evidence as it was completed. I visited after it was fully occupied and there didn’t seem to be any evidence of vandalism then. We never got any feedback as a practice on you should’t have done this or that. Perhaps we could have foreseen some of the possible problems. At the time disability access wasn’t an issue. It should have been but it wasn’t. Now that wouldn’t be allowed. You have to provide much more facilities. Unless the facilities are provided people will abuse what’s there and definitely need alternatives. Maintenance has been the problem in almost every area of social housing that was built at that time and subsequently. it’s one thing to realise and provide housing for umpteen people, but then to not maintain the estates or keep them going. It was very short sighted. That’s why social authority housing has all but disappeared because nobody is prepared to take on the long term issues. It was a product of its time in the way it dealt with a big housing issue, sub-standard housing. And hoping to provide the mix of urban renewal, accommodation, green spaces for enjoyment, kids playing and all the rest. This was just one of a number of schemes which were resolved in different ways but the deck idea was a sort of constant thing throughout. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Estate, which is due for demolition now, was one of the background influences on the concept of Lancaster West. There was also a reference perhaps to the Lillington Gardens estate just off Vauxhall Bridge Road. That’s a famous development by Darbourne and Darke which I think still survives very well. Ideas of large scale redevelopment and housing tend to go through different phases of acceptability or relevance and it’s very difficult to look back and say that was the right decision to make. In some cases it was the only option either because of financing or government pressure or politics. But I would have thought that if the masterplan was completed it would have provided a better result than has eventually arisen. But it’s very difficult in hindsight ever to say. Pauline Wearden whose husband was the lead architect for Lancaster West estate masterplan and building stage 1. Pauline Wearden: Clifford was born in Preston, Lancashire in 1920 to working class parents. His father was a plumber and his mother was in retail with a profitable cafe. Clifford was his mother’s golden boy and she paid for him to go to university. There were no architects in the family. It just came thorough Clifford. Clifford studied architecture at the University of Liverpool from 1938-40 and 1946-48. He was very fortunate because that was a prestigious university in those days turning out many famous architects and Rhode Scholars. When war broke out, he immediately volunteered. He had a lovely war, mostly cocktail parties. No. No, He did have a lot of tragedy and he saw his best friend shot down. Clifford was a pilot in Air Command. He had travelled as a student on what they call the Tour and he’d been to all the classic places but during the war he also saw some exotic places. From 1949-54, Clifford was chief-partner for Sir Basil Spence. This was when they got the commission for rebuilding Coventry Cathedral and Clifford was given the job of preserving the ruins. He was very proud of that. I don’t know what brought him to London. But he had no home and went to International House Hostel. He lived in a hostel for years. He didn’t have anywhere stable until he bought his top-floor flat in Argyll Road, Kensington. Then he came across this derelict house on Homer Street, Marylebone. They were a row of 6 Georgian houses in that street and the property owner wanted him to do up the other houses as well. So he worked on those and then bought one of them. That was probably one of of his first jobs alone. By the time I came on the scene in 1965, Peter Deakin was there and Derek Latham was a student. Clifford built an office at the back of the house. A very nice studio designed by him which was contemporary which might have looked strange at the back of a Georgian house. This is where the master plan for Lancaster West was prepared. Eventually the practice had to relocate premises as there were twelve in number. It was like I married twelve men because they were always in our house. Clifford came home one day and he said they are blowing up one of the houses in North Kensington. And we said - what! And he took us all in the car at night. The director was just about to film the house being set on fire and demolished. They had all the safety people and security and police vans. We had to creep through the security set up. Nobody had invited us but we said we wanted to see it. They had built a false house to make a cul de sac and when you looked it was completely false, but it didn’t look it. So we were exactly there for the big bang. The children were thrilled. I can remember seeing big cameras, arc lights, just like you dream for an outdoor film set in the dark. It was typical of Clifford to have the children up. He didn’t want them to miss anything. However, I don’t think Clifford ever saw the finished film, Leo the Last. He wasn’t particularly interested in films. Lancaster West was his first very big job. But he got into the mould very easily. He more or less expected it working with Sir Basil Spence and being up there with all the old Liverpool people. He was very much an architect’s architect and he felt that his time was coming. Some architects don’t like meeting their public, but he was very good at that. I think he listened to them. One of his ethos things at university was social housing. So he felt very strongly about it. Of course, affordable housing it’s called now. I think he’d be absolutely disgraced by some of the policies such as right to buy. However, I don’t think he was a socialist. I don’t even know his politics but he was fairly traditional in many ways. We married in 1969 and you took over your husband’s life or it took over you. He was doing very well in 1969 but of course it’s a hand to mouth existence. Your only as good as your next job and the 70s were quite stressful and then in the 80’s the work fell away. We had to economise and got rid of a car. We were trying to think of other ways to save money. It’s very difficult when you’ve been having a certain lifestyle and it worried him terribly. He used to worry about what might happen and I always felt that was a terrific waste of time. He lost quite a lot of sleep over some jobs. Clifford believed that the tower block at Lancaster West was demolished. We drove past it on the Westway. He said it’s no more. And I remember saying to him, that we should have gone to see it come down. In the family we all thought it had gone but one day my son said it was still there. I think he would have been relieved, quite honestly, if it came down. He didn’t want it built. He didn’t want to be in this era of tower blocks. He felt very strongly about vertical living. It wasn’t right. So I don’t think he took any pride in it, except that it was not a bad building and it did work. I’ve never really appreciated that Lancaster West was landscaped or intended to be. In the model of the estate that my son has hanging from the wall in his house, there are little trees made by Ken Price. And they always put trees in as their panacea for making it look homely. But it did look good in the end and not as desolate as it might have been. I’m afraid to say that driving past on the Westway is the nearest I’ve ever got to seeing the estate. I’ll have to go. The best way is to walk around, I imagine. I'm going to end this essay with a few extracts from residents who live on Lancaster West estate. We are not now talking about perspectives and plans or so many housing units that can be redeveloped. We are talking about homes. People who have planted roots, raised their family and want to retire with peace and dignity. These flats and houses that were designed and built in the 1960s and 70s are now home to a diverse range of people who want to live in one of the richest boroughs in the universe. They deserve to have the final word. One hopes that in 10 or 20 or 40 years time, that they are still living in the area, as the new kids on the block are contemplating how to buy into the next cycle of housing redevelopment. Christine Richer, resident of Hurstway Walk: My mother was an African-Welsh woman and my father was black African American. They met after the war in the West End. Two weeks after my 18th birthday, I came to London and I landed in St Stephen’s Gardens in North Kensington. Massive, one room bedsit with the kitchen in the corner and the mice. The mice were hell. That was my first living in a big city. I came to the estate in the 70’s. Funny story. The first day I came here to meet the electrician and the gas people. No one turned up. I end up sleeping on the floor. And I had the most vivid dream of my life. I wake up in this dream watching my coffin being carried down the stairs. I saw these two shapes and they were my daughters. But it was very pleasant. I thought this is my place. My place on earth. I’ll live here till I die. As a child, I moved a lot. In Grenfell Tower there was a really nice club, like a residents social club and my partner at the time was on the Committee. That was my first introduction to the estate. It was full of different people who knew each other from the neighbourhood: Moroccans, Africans, blacks, whites, Portuguese, Spanish. I think with my involvement in the resident association and Estate Management Board, when the children were young, they have learnt a sense of community. They would always come and help me if I say I’m doing something with the R.A. Volunteer themselves, wash dishes. The garden down there was very important to me and the kids. They spent their formative years down there with or without me. We had family parties, barbecues. That living space outside there meant a lot to me. I do believe that we are going to get knocked down as all this gentrification is happening all around us. And we are not a Victorian block which is a beautiful thing. We are a 1970s fling them up, fling them down block. I don’t know where I’ll end up. That’s the biggest concern for me. That makes me stay awake at night. That makes me cry. If they could build another block, 4 or 5 streets away, where I knew I was going to be rehoused. It could be Manchester. All my close friends who live on the estate, only about 3 are here. Everyone’s gone. It’s a changed community. I haven’t always loved all the neighbours. But the neighbours that I have liked and I’ve made friends with, we’ve loved living here. The old families who brought up their kids and their kids have grown up and moved away. It’s been a home to a lot of people. Edward Daffarn, resident of Grenfell Tower: I’ve lived in Grenfell Tower for over 15 years now but I’ve lived in North Kensington, Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill Gate, my whole life. I found education was quite a therapy. I became a social worker for about 7 years. And then sadly my mum, got motor neuron. so I gave up work to look after her. I haven’t got back into social work. But what I have got involved with is housing issues on Lancaster West and in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The stuff that we’ve been doing on Lancaster West started as a result of the Academy being imposed which was 5-6 years ago. When we first started there was virtually no community groups around. Five years later there's a lot of community activism because of what’s been happening in housing. Westway 23, Focus E15 Mothers, The Guinness Trust down in Brixton, Our West Hendon, Sweets Way and all the radical housing network. There’s all these different struggles. On the 24th June, this year, 2015, the council passed a motion in the full council meeting saying that they were going to go ahead with the destruction of all low density social housing in North Kensington. Low density means this, They’ve been built nicely, giving people some space inside and with some green residential amenity outside. Trees and green space for their children to play in. Low density housing. It’s not anything else. It’s just nice estates. It will be interesting to see what will happen to Silchester. Because sooner or later, one community is going to say, and it only needs one or two inside that community to lead the rest - just to say - your going to knock our houses down - oh yeah! Oh yeah! Let’s see about that. North Kensington has a good history of not just taking these things lying down and when people finally wake up and realise what is going on, maybe the council will get a bit of a shock. They call Lancaster West the forgotten estate. And it hasn’t been called the forgotten estate for the last couple of years. It’s been called the forgotten estate ever since I’ve been on here. If it had been maintained properly, Grenfell Tower and the finger blocks are quite beautiful. Particularly if you live here. I don’t know the architect that designed them but they have architectural merit. I don’t know how you say you love your home. You love your home. If we remember what happened in 1974-75 by the signs, Get us Out Of this Hell, then maybe the Grenfell Action Group blog, the protest that we did going up to Holland Park Opera, the procession of Westway 23 along the Westway, will be things that in 25 or 30 years, people would look back and say, when they took away the stables, the Westway Stables, when they took away the children’s centre, didn’t people say anything. And they get on the computer. Look I found this Grenfell Action Group. Yeah they did something, And they did this demo. That will inspire the next generation of people who would care about their community. Clare Dewing, resident of Talbot Grove House: My parents were squatting in and around the area. Mum became pregnant with me and said right Paul, get us a flat now. My first steps were actually in the flat that I live in right now which I share with my mum. When my mum walked into an empty house, she put me down. I stood up and apparently I ran just clean straight across the room and those were my first ever steps. Growing up on the estate, we were told never to leave the estate because I’ve always viewed the estate as two halves. My half which is Talbot Grove house, Verity Close and the other half, the finger blocks and Grenfell. So when we were a bit naughty, we used to go on the other half and do knock down ginger and stuff like that. I did probably knock on Christine’s door. About 1993-4, I was quite naughty and I’d be going to clubs, sneaking out. Mum and Dad wouldn’t know and my friend would say she’s staying at my house and I’d say she was staying at her house. Teenagers you know. I do remember it being quite scary trying to sneak back into Ladbroke Grove and we got mugged a couple of times, got followed a couple of times. But in recent years, I do feel the safety has improved. There used to be crackheads on every corner, all along Portobello. But that kind of edginess gave it a vibrancy which unfortunately, I think, it’s almost gone. About 5 years ago unfortunately my dad became ill and I moved back to my parents house to look after my dad. We’d always known that my mum’s memory wasn’t too good. But it was only after my dad died that we managed to get her to have a full proper diagnosis that it was early on-set dementia. Mum’s going well. I think the progression of her dementia has slowed and I think that’s down to a combination of exercise, good food, good stimulation. I wanted to join the R.A. because it got me to kind of flex my muscles again in using organisational skills in a different way and and just giving back to the community that’s helped me out so much over these last few years. Kensington and Chelsea are an amazing borough to live in especially the way that they look after the older population. I also had a bout of depression as well and the services that were available to me are not available to some of the people that I’ve spoken to. So I feel that the support is there and that’s why I’m really surprised about the state of the housing here. It doesn’t marry with my experience of all these other services. I think Kensington and Chelsea need to be aware that if they just sell all the properties off and make it into a million plus houses, that what draws people here, what draws people to Notting Hill, what draws people to Portobello, would just be gone. It is that mix of culture that drew people here in the first place. That made it trendy. That made it hip and cool to hang out on an evening. It’s just going to turn into Kensington High Street and be replaced by Cafe Nero’s and shoe shops and places you can’t actually afford to shop in or buy food in. What we are trying to do as a RA here is to lay the foundations now. We're trying to get ourselves prepared and ready so that when the regeneration does come that we are ready and we've got some ideas together. Hopefully we can influence them which would be great. On Saturday 14 April, 2007, the sun set over the resplendent fields of a Northumbrian landscape. The master and mistress of the land were not at home. Sir Humphrey was away for the weekend and Lady Humphrey will not stay on her own in the twelfth century castle. Chillingham is reputed to be haunted.