|

Jordan Stone, film maker in conversation about his parents, Barbara and David Stone,

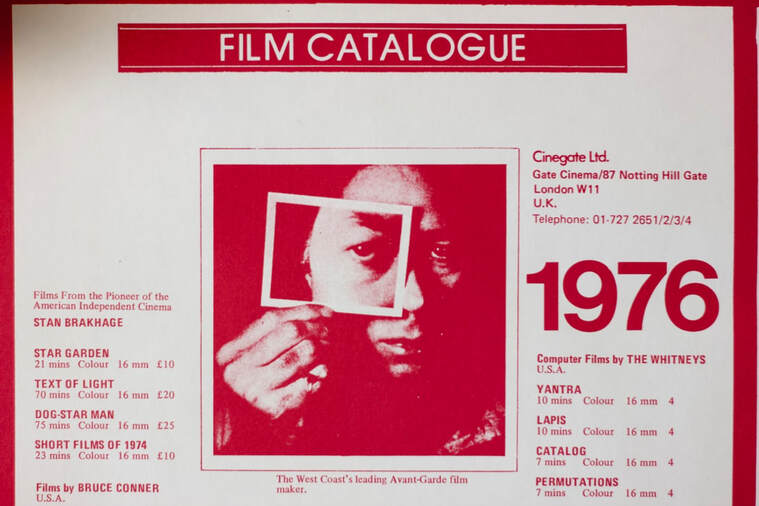

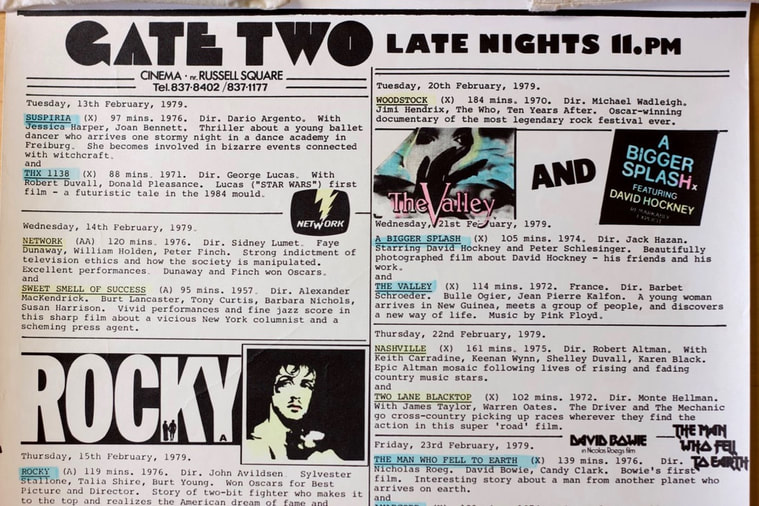

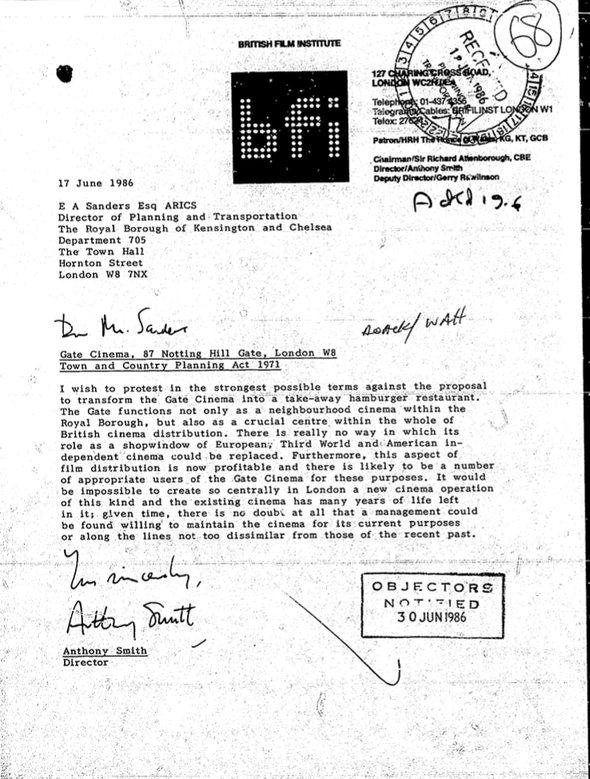

who opened a pioneering art house cinema in 1974 at the Gate, Notting Hill. The family moved to England in 1971. I think what my father originally wanted to do was to open a New York styled delicatessen in London where you could get bagels, cream cheese, smoke salmon, pastrami on rye bread. That was his original plan. But my parents had a passion for underground, avant-garde and independent cinema. They had been attending film festivals from the very early 1960s, whether it was Cannes or Venice. They were the creators of the Spoleto Film Festival in 1959. And so they were very familiar with European directors, the press, film critics, historians and writers. They had also been involved in the various film art movements in New York. They had made films themselves and also produced films with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. So at some point, they realised that there was this huge area that was missing in film exhibition and distribution. And that was their talent: to create a distribution and an outlet, a cinema, at the Gate in Notting Hill for showing these independent films. At that time films were still being dubbed for UK release. And there were films that would not have found a way out of their country of origin. My parents combined their passion with the business. But taste has to obviously come first. You have to create that and show it to the public. In America there is also a certain passive-aggressive approach to business whereas in England, it's a lot more passive. Maybe aggressive is not the right word, but they were more proactive, a term used today, but not used then. And so, it's like everything aligned at the right time. A cinema became available for them in Notting Hill. It was called the Classic. I think the previous owners couldn't afford to keep it going and that was the moment to strike as it were. What you have to realise is that the distribution company Cinegate and the Gate Cinema went together. What we distributed was what we showed. In the Cinegate catalogue, we had a huge collection of experimental cinema from Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Stan Brakage and the Mekas Brothers. And what also was remarkable were the late night double bills, mainly from other distributors, mostly American classic and cult films from the 1930s up to the 1970s. My parents created this culture of late night screenings that started at 11pm and went on till 2 or 3 in the morning. No one else was doing that. I still bump into people who tell me that they saw this film 25 times because they went to the late night program every other night. And unlike other cinemas, the Gate was open 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year including Christmas Day, New Year's Day. We were open every single day. Other cinemas started to copy us with late night programming. The Scala started doing the all-nighters at weekends. The Electric that was just down the road from us, on Portobello Road, was a repertory cinema. Peter Houghton who ran that cinema had perfect taste. It was an absolute fleapit at the time, but they created their own cult even before the Gate. But it was very different from our cinema. They would show a week of Hungarian movies and then ten days of German New Wave and then a week of Charlie Chaplin. And they showed a lot of films that we distributed that fitted perfectly into their programming. But they weren't opening movies. We were and they were independent, art house films. There is a nice little story. The Electric went through many periods of running out of money and my father insisted on lending them some. It was a real beautiful little moment unheard of that one cinema would help out another in the same area. I don't think my parents started up their operation thinking in a competitive way whatsoever as opposed to enhancing the whole concept of British Independent cinema. A few years later, once everything was going well, my parents had a good relationship with EMI and Barry Spikings, its head at the time. He had produced The Deer hunter and EMI had a cinema in Bloomsbury. But they had no idea what to do with it. They didn't know how to program it and so they gave it to my parents and the rent was completely reasonable. After a while, Gate Bloomsbury (now the Curzon Bloomsbury) was divided and had two screens. Then some short time after this, the same thing happened with Rank who had a cinema on Camden Road. My parents took that over and it became Gate 3. And finally, in the basement of a Mayfair hotel, there was this wonderful, tiny, super-exclusive cinema with just 40 or 50 seats. That became Gate Mayfair. When we first opened in Mayfair, this must have been about 1980, Mephisto, which was a huge success and went on to win Best Foreign Picture Academy Award, that was shown at Mayfair on a second run. I think it was playing for 9 months. My sister says it was shorter. But it felt longer. The majority of art house movies were definitely not American. The only American art house movies would be ones made by first time directors who sometimes had a distribution deal with a major company. And so the only way you would find out about these films was going to film festivals where the producers would be at Cannes, Venice or wherever they were trying to sell their films. My parents would be looking out for these types of films. Jonathan Demme was a Roger Corman protégé and his first couple of films we opened, I think we even distributed them. There was CB Radio and Melvin and Howard.

There were moments that brought great controversy that fed into the success and mythology of the Gate. Derek Jarman's first film, Sebastian, for example. The dialogue was in Latin and there were scenes of men making love to each other. It was definitely not pornographic, definitely an art film. But they were under a lot of pressure from the Board of Censors which was run by a guy called James Ferman, who was also an American. There wasn't much love between him and my parents. There were lines around the corner of the Gate Notting Hill because the only film prior to that which could be conceived of as a homosexual film was A Bigger Splash. That was a film about David Hockney and we ended up showing that at the late nights. But Jarman's film was a full-on feature film and made by someone we had never heard of. We had a lot of celebrities and famous people coming to see that film in 1976. And then a couple of years later with the Oshima film, In The Realm of the Senses, where you had two lovers making love throughout the film and in the end the girl cuts the man's penis off. That film was refused a rating by the Board of Censors. My parents came up with a way around this; which was to turn the cinema into a club. So people had to be 18 and pay a minimum 25p or 50 pence membership and then they could buy a ticket to see the film. But as kids growing up, we were told to stay away from the cinema because my parents were expecting to be raided by the Home Office every day. I also know that for that film to be seen, they put together a list of very well known people who had signed a petition demanding that this film be allowed to be shown to the general public. This was not just film people or from the entertainment industry, but also politicians.

The regeneration of Notting Hill had not happened at this time. That was much later. Everyone who was everyone was coming to the Gate. You had to imagine Harold Pinter living down the road and he would want to see everything. We had people who loved film and wanted to see films that the film critics were writing about and that would not otherwise have a chance in a lifetime of being released in its original form. We had punk musicians, artists and photographers, a lot of theatre people and of course, the general public.

My father was always charging a little bit more at our cinema. There was a reason for this because we were showing films exclusively. I think our first ticket price in 1974, for Fassbinder's Fear Eats The Soul that opened the cinema, was 60 pence; but after a year or two, this went up to 90 pence. And of course, we were an art-house. You were going to pay to see art. He wasn't trying to rip anyone off. It was a very exclusive approach however. And my father was actually quite short and the rows in the cinema were based on his leg- room. What he wanted to do was get as many seats in as possible. So we did have a reputation of having very thin rows, but that was based on the fact that he was quite short. I think we had 282 seats. If you look at the Gate today, my father would be surprised what it turned into with the sofas, the tables, the feeding and drinking during the film. I remember we were one of the first households that had a video projection system at home because film-makers from around the world were sending us films to watch. We grew up watching films that never made it into distribution. We had friends coming over to the house who never knew what a video was, VHS or Betamax. And we had equipment that was flown in from the states. This was set up in one of the rooms in the house, a screening room. Actually whether we lived in New York or London, my father always had a 8mm and 16mm projector set up in the house. Saturday night we would be watching films. They were very social events with film critics, Chris Petit, Nigel Andrews, David Robinson and filmmakers. We were also very friendly with someone who worked at the National Film Archives and every weekend he would come with a 16mm print under his arms, something that was 40 or 50 years old. My mother would do a big dinner and then we would all sit and watch the movie. That was a large part of the Stones' reputation. From the age of 11 or 12, I was working in the cinema and the Cinegate distribution dispatch office. Cleaning the films, packing them up and taking 16mm and 35mm prints to whoever was renting them. My brother and sister were also working with me in the cinema, making popcorn, tearing tickets and in the projection booths. I was also an actor and then at the age of 16, I had already started a video production company. Then a producer friend of ours asked if I wanted to be a runner on one of his films. That's how I started making my way up as an assistant director and have never stopped. I still am a first assistant director on feature films, commercials, and music videos. I was based in L.A. for a long time, too. And now I'm operating out of Italy. I look after a lot of the filmmakers who come to shoot here and I've turned that role into a type of service producer as well. I've produced projects with Sofia Coppola, Mike Figgis, Spike Lee. I’m a filmmaker myself. My films are not commercial and that is a result of most of my life working on other people's movies whom I've learnt so much from. The lesson that my parents ingrained in all of us is that you have to do what you feel is right - for you! And we grew up in an anti-commercial atmosphere. Anything that was American studio was the devil. We knew from the beginning that people who went to America to make films, compromised their creativity, because a producer or the studio said we want more tits and ass and more violence. However In the last 5-10 years in America, I've found that there has been a rush of films that are very independent. But most films can't be made unless they have a distribution deal. The film studios and media companies will put money into a film for its distribution rights. The filmmakers are not dictated to as badly if it’s a non-studio film because they have got the money just for distribution. So what's happened is that it's allowed much more of an independent approach to American filmmaking. There are many different structures to put a film together. You can raise money privately; you can raise money through pre-sales, through distribution sales, money from the studios, from several companies or countries. Tax incentives. It's a whole quagmire of things before you can get interest for the project. But if American studios are involved, the more control they have over the finished product. It's a different process for a European or a Chinese filmmaker. I saw a space to do commercially what my parents had done in London during the 1970s. I ended up for a while programming two cinemas in Milan in the same style as the Gate. I also created CinemaStone and this is not just a production service company, but it also dealt with film and event programming. I grew up doing what I was destined to do.

Barbara Stone Unpublished - trailer for film written and directed by Jordan and Veronica Stone

Jordan Stone's website Poster art work from the Barbara Stone Archive recently deposited at King's College, London And which will be available to view over the coming years Drawing by Constantine Gras: When a kiss fans out Watercolour, pencil, ink 9.5 x 12 inches, 1994 Link to film event called Emotion and Economics - A history of the Gate Cinema

2 Comments

Obituary for Nigel Whitbread (1938-2019) Modest, talented architect with a passion for walking, travel and sports cars Nigel Whitbread was born in Kenton near Harrow. His parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington and the family moved in 1949 to be nearer the shop. That was Nigel’s home from the age of ten to his death. After attending Sloane Grammar School, Nigel joined the firm of Clifford Tee and Gale where he served his apprenticeship demonstrating a great talent for drawing for which he became renowned and which he taught later on. He went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this he became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. But it was Nigel’s time at Douglas Stephen and Partners that was the most influential time in his career. It was a small practice, but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that Nigel worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. Nigel remarked that it was like going to a club with the bonus of doing terrific work. In the early 1970s Nigel went to work with Clifford Wearden and Associates on Lancaster West Estate. It was a huge job for a small group and unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. The whole scheme had been well prepared by the time Nigel joined to lead the team in designing Grenfell Tower. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, he thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. So insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, were lifted up and put into place with cranes. The concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams, all holding the building together, were also designed in response to Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968. Nigel remarked that he could see the tower standing in 100 years time. In 2016, Nigel visited Grenfell Tower at my invitation, when I was community artist in residence. He visited residents in their flats for the first time and enjoyed hearing how they viewed the spacious flats (built to Parker Morris Standards) and the stunning views. It is impossible to know the sadness and anger he must have felt as he witnessed the tragic fire that occurred on 14 June, 2017. Nigel retired after working at Aukett Associates for 30 years. His projects included the Landis and Gyr factory North Acton and Marks and Spencer's Management Centre Chester: two award winning buildings he co-designed. As a director of the practice, he had a lot of responsibility, but spent time mentoring younger architects. Nigel was happy in his retirement and in his travels over many years, including recent trips to India, the Himalayas and Colombia. He continued to use his skills in helping his local resident’s association draw up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan which was accepted by the local authority under the Localism Act. He will be remembered by his friends and family as a dignified, humorous, generous and inspirational man. Silchester and Lancaster West Estate Open Garden Estate Weekend, June 2016

Here's a link to an interview with Nigel and the other architects of Lancaster West Estate. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed