|

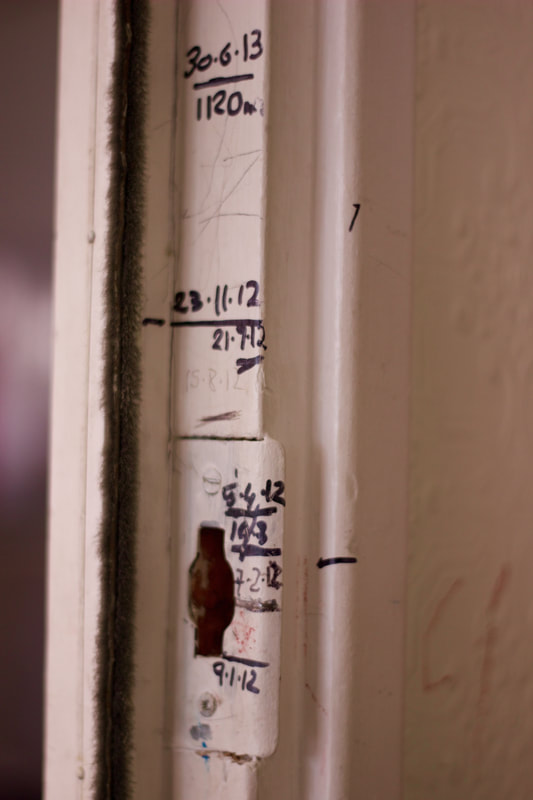

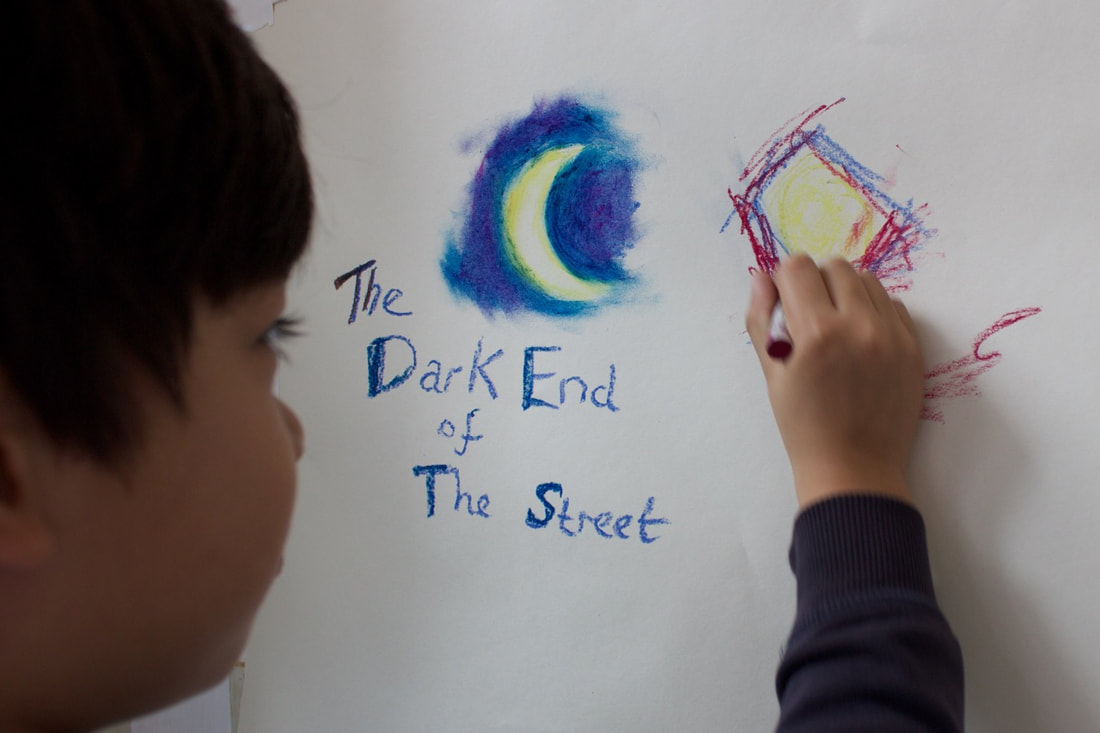

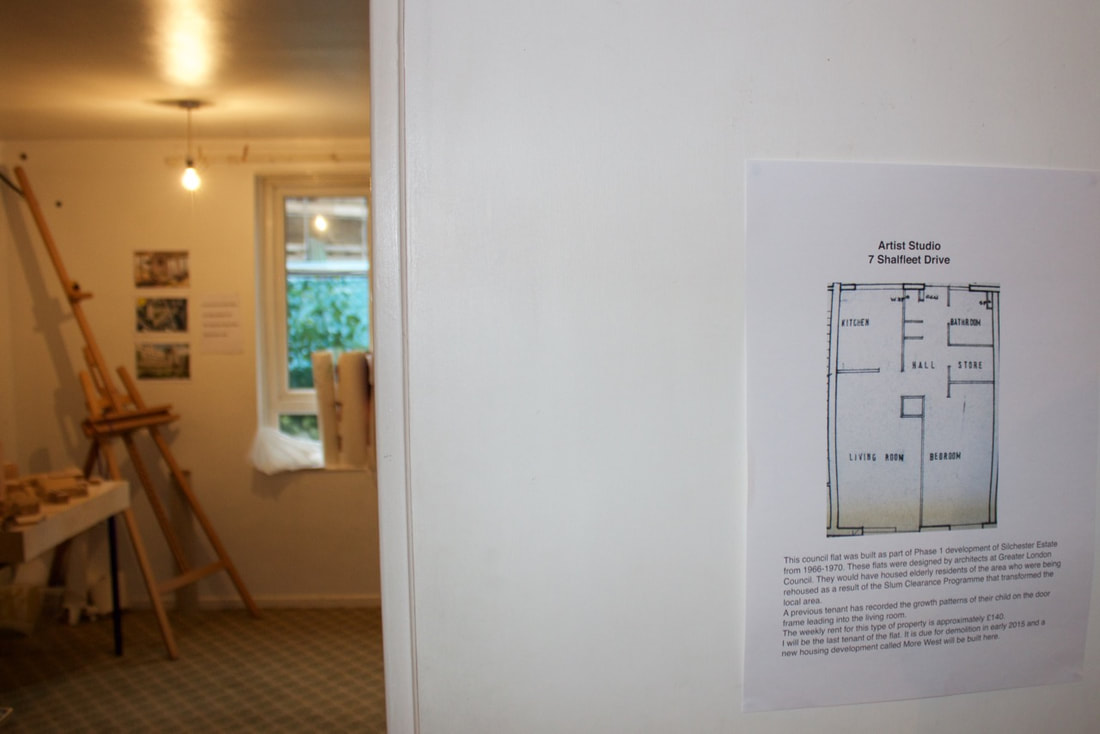

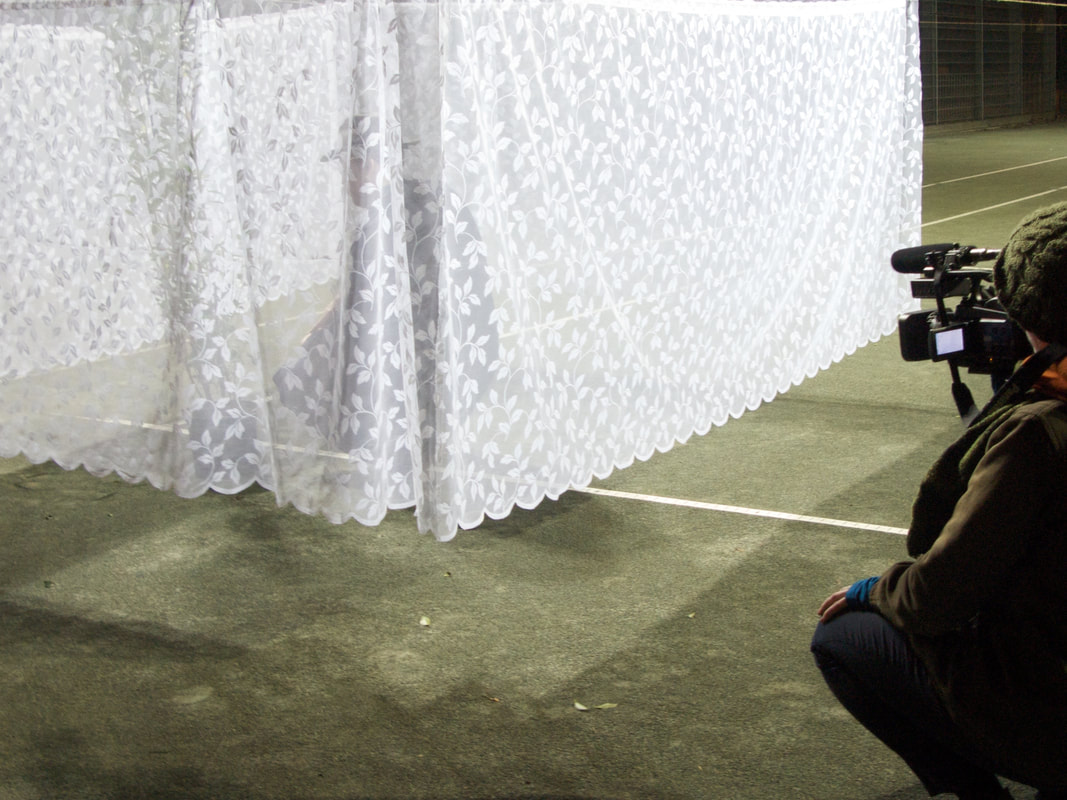

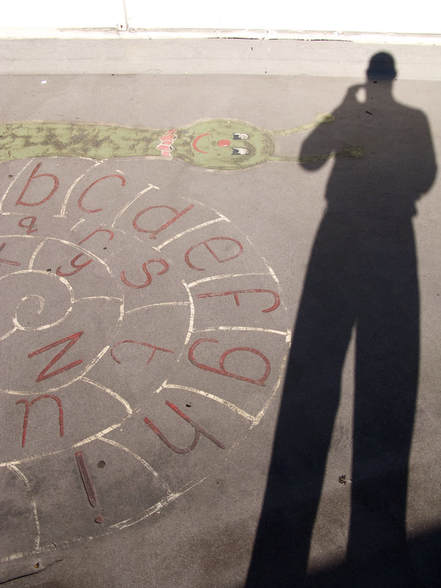

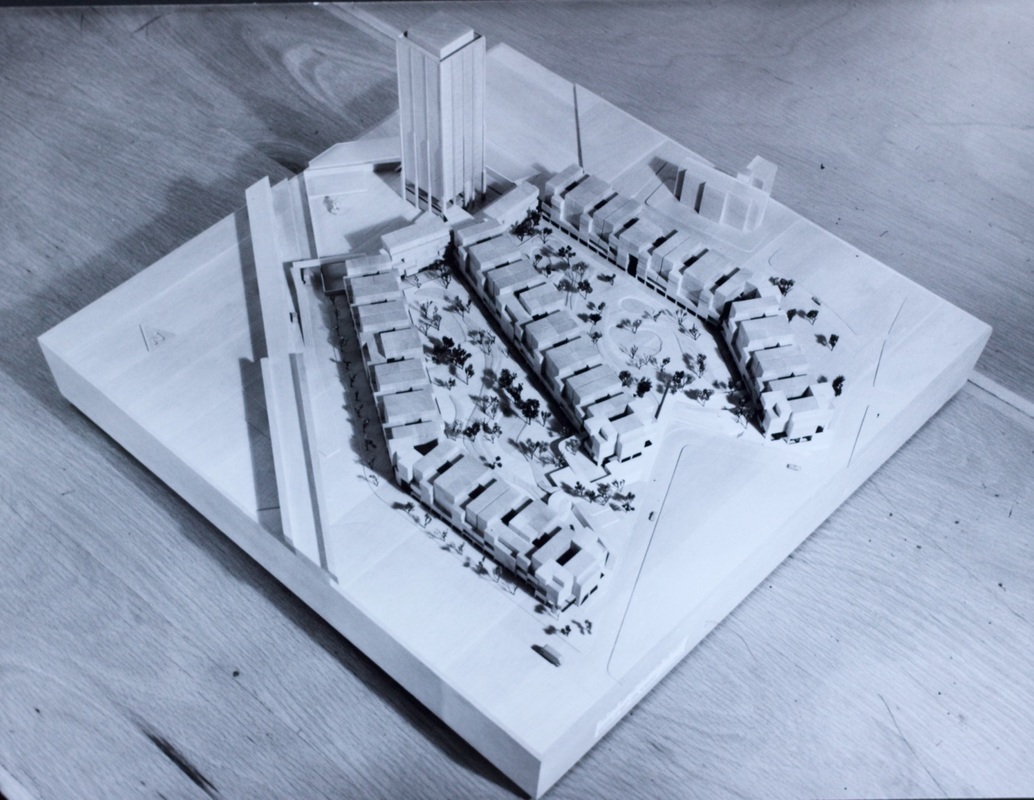

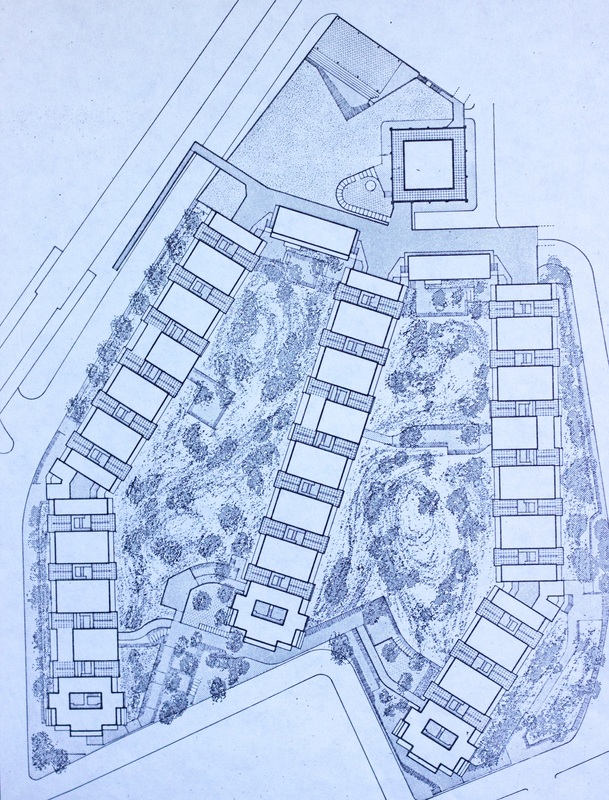

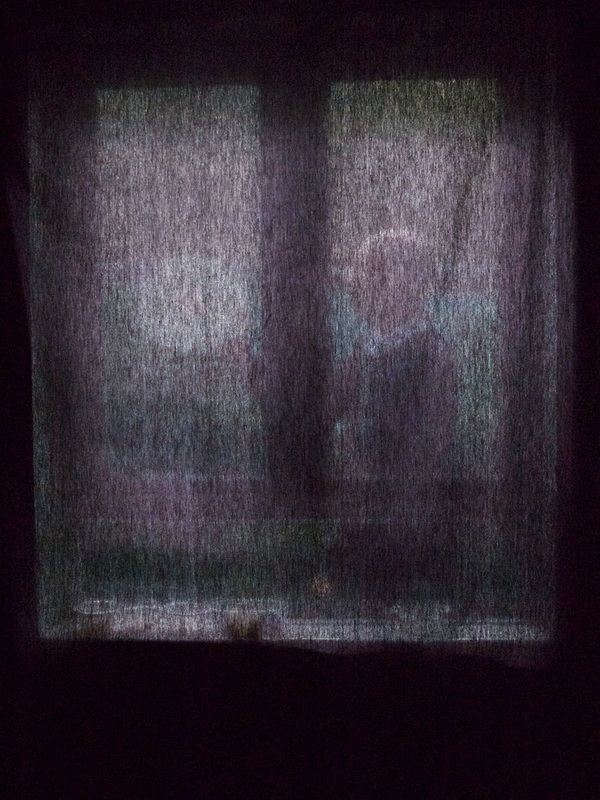

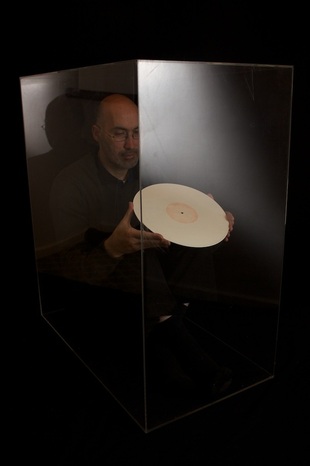

Reflection from artist studio as More West is being built The chronicle of a child's growth recorded on a door frame Photos taken at 7 Shalfleet Drive, 2014 Can a building have a soul? If so, how might one measure this on a scale of soul from 1-10? One? Nah! This is just a plain pile of functional brickwork or unloved concrete. To give it a Presidential seal of approval, "a shit hole!" Five? Maybe given its provenance and state of use, there is a connection being forged between property and person(s). Perhaps a bog standard church and appreciative congregation might fit this bill. Ten? Now this might be hard to put into words. Some otherworldly sensory experience of an English castle made in heaven. A building that has survived carbuncular judgment and phases of regeneration. A cave you have carved with your own hands or flat packed assembled. Excuse these digressions, as this is completely uncharted territory for this author and a subject matter reserved for the confines of a philosophical department in a city of dreaming spires. Let us return to North Kensington terra firma. This blog is about 7 buildings, most within several hundred yards of each other: one was built as a film set and several have long since been demolished. They are St. Francis of Assisi church (c1860), 1-2 Whitchurch Road (1863), 2 Silchester Terrace (?-1960s), 7 Shalfleet Drive (late 1960s-2015), Latymer Nursery (late 1960s-2013), Grenfell Tower (1974) and More West (2016). The question I ask is do these buildings, historic or contemporary, have a recognisable soul beyond their outer facade? I have worked as an artist in three of them, one as a rented studio flat. While looking at spiritual qualities, I want to relate this to how I have used them in my art, the intersection of aesthetics and politics. To complicate matters, I have to declare from the outset that I'm not mystically inclined or believe in angels. However there is definitely more in heaven and hell than can be dreamt of in my atheistic philosophy. 1-2 Whitchurch Road House built for stain glass artist Nathaniel Westlake in 1863 Currently a St Mungo's house for homeless people St Francis of Assisi church Side chapel roof designed by John Francis Bentley, C1860's House for Nathaniel Westlake displayed at the V&A Museum, 2015 Acetate sheets, 3x3 metres Let us return back to that proposition. It is a line from a film, completely unscripted and conjured forth from the consciousness of the gardener at Lancaster West estate, Stewart Wallace. When I asked him how he knew this building had a soul, there was an even better quip: "I wouldn't be an angel otherwise.” The soulful building in question was 1-2 Whitchurch Road. Stewart had been living next to it for decades and said if he won the lottery, he would buy it and lord the manor. The building was the home of Nathaniel Westlake and designed by his close friend, the architect, John Francis Bentley of Westminster Cathedral fame. So we have soul pedigree here. During the 1860s they were both converts to Catholicism and working on St Francis of Assissi church which was a stones throw away from this house. This was a part of London noted for its piggeries (pig farmers) and potteries (brick works) and undergoing urbanisation with the coming of the railway and the growth of an Irish community. Westlake did not stay long in his dream house and we can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. Amazingly this grand looking house, that is now listed, was once a squat and is still used to house homeless people. The building was a key location in my film, Vision of Paradise (2015). This was a meditation on housing and community using Dante's concept of heaven, hell and purgatory. In 1863 Westlake was working on his stain glass design, The Vision of Beatrice, to illustrate a scene from this story while living in the house on Whitchurch Road. This panel was collected by the V&A Museum. As an additional homage, I made an installation called House of Nathaniel Westlake, comprised of 30xA2 acetate sheets incorporating images of North Kensington buildings. Soul value: 8/10 for its origins and continued charitable use when this type of property would be snapped up by oligarchs and venture capitalists; although shame on them as they would not want to live cheek by jowl next to an estate! As mentioned, Bentley and Westlake put their heart and soul into St Francis of Assisi church. This is a small church with connected buildings on a tight plot of land, but the overall design and interiors sing of the unique talent of its guiding architect and artist. This is self-evidently a soulful building with a wonderful acoustic quality. For the remastered film soundtrack to This-That, I recorded two singers here performing a duet called Duo Seraphim. 9/10. Staff from the V&A Museum help me prepare for a community artist event 21/08/14 7 Shalfleet Drive, W10 6UF Mayor of RBKC meets local residents and architect of More West, Joanna Sutherland Demolition of Shalfleet Drive, 12/02/15 During 2015, I was the V&A Museum community artist in residence based at Silchester Estate. The first phase of regeneration was occurring in the area with the building of More West. I was embedded here with a studio flat at 7 Shalfleet Drive. This was part of a lower and upper deck housing block with 3 room flats that must have been designed for a pensioner or a couple, certainly not a family. So did this flat at the end of its social life have a soul? I would rate it 7 for its cosy uniformity of space, perfect for an artist who tried his best to give it back to the community with a series of bespoke art events that included film screenings and drawing/music happenings. Centre stage in the living room of that flat was a simple map which had photos of all the listed buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The addition of Silchester Estate on this map was the radical touch that only the locals noted. This map was a popular attraction to the visitors, including the then Mayor who came to an event called I Want To Live, Draw Me A House. Before she arrived, the police dropped by to inspect my premises. It seemed they had valued the spirit of the location in terms of a negative. It was an unknown precedent for Mayors to visit council flats on estates in North Kensington, even ones about to be regenerated. I was told this was a first. Film projection of Home about the last house demolished for the building of the Westway and Silchester Estate. It was screened at Latymer Project Space, formerly a nursery on Silchester Estate and soon to become More West. Photo by Emily Ballard, 2012. We move onto a house that now only survives as an archive photo. It was taken by the actress Mary Miller in December 1967. She wrote an accompanying letter that read: “I remember taking this picture of a house and a tree amongst the rubble and desolation of the early stages of the motorway from Bramley Road, looking west. It looked so forlorn and I admired the tenacity of the householder. i seem to recall it was an elderly man. There was something about him in the local paper of the time (I can’t recall which paper exactly). But a few weeks later he had succumbed to the pressure and the house was destroyed - also the tree. I think it all happened round about the time they blew up Maxilla Gardens for filming with Marcello Mastroianni.” This had all the ingredients to inspire the cinematic imagination. A small house that was left standing while those adjoining had been demolished. That solitary man with raincoat and hat standing outside. The corrugated sheeting. Even Mary’s reference to Leo The Last that was being filmed near by. I simply had to tell the story of this photograph. I presented this as a short film pitch to Latymer Projects. They accepted and I made Home for their inaugural exhibition. I acted the role of that homeowner from the photo. You don’t see me/him clearly as we move nervously around a house and twitch at net curtains waiting for the developers to serve us an eviction notice. At the end of the film, there is a panoramic shot of a net curtain house constructed on the Westway tennis courts, on a spot that marked the real life location of this lost house. Given all these resonances, I would have to evaluate this lost house in the photograph, as an 8 for its elegiac soul. Set design from film, Home (2012) Cinematography by Natalie Marr Film still from Leo The Last (1970) with Glenna Forster-Jones (left) Filmed in North Kensington and on Testerton Road before its redevelopment into Lancaster West Image kindly reproduced by Park Circus Limited Leo The Last is a quirky, enigmatic and powerful film that dramatically deals with race and social conflict. It was made by John Boorman in the late 1960s. It is a film of its time with hippie experimentation. Yet also profoundly prescient in that it tapped into the zeitgeist of the area. It remains a touchstone for thinking through art and redevelopment; it inspired me, as I feel certain it will continue to do so for other artists. The film makers were given unique access to the streets of North Kensington just prior to its slum clearance and they created a false house on Testerton Road. This had a white classic stucco facade and contrasted with the rest of the derelict houses which were painted black. This is a colour film with an impressive monochrome palette. Leo is the last in the aristocratic line and for the opening sections of the film peers out of his house with a telescope onto the world of his opressed black neighbours. He becomes radicalised by observing their plight, especially when he discovers he is their exploitative landlord. In true 60s fashion he decides to stage a revolution with destructive consequences. I felt a great affinity with Leo. As an artist, I was using my camera and drawings to reflect on changes to my social environment and in the process was being radicalised. I was getting a deep understanding on the cultural richness of life on these estates. Yes. There are social challenges, but these were not the sink estates as portrayed by politicians and councillors intent on running them down and forcing through regeneration schemes. As part of my community engagement, I got hold of a rare 35mm print as the film was not available in this country on DVD . I screened this for residents at the Gate Cinema (which is in the Notting Hill and not the Dale part of the borough). After watching the film residents from the estate joined me down at the V&A to create clay houses in response to the film. I was able to use this as part of an installation display at the museum. I have to give this film-set-building a 10 on the soulful scale. It has mythic and poetic qualities. It was built in order to be destroyed. Many local residents and the architects of Lancaster West Estate came to watch the impressive finale as the house explodes in flames. What did they think and feel watching film makers turn their former homes into a film set prior to its demolition for the building of Lancaster West and Grenfell tower? The soul of their buildings disappearing at a rate of 24 frames a second and then projected at cinemas in the following year to a largely unappreciative audience and box office. Latymer Nursery converted into Latymer Projects 154 Freston Road, 2012 (Bottom photo by Sandra Crisp) I also developed a strong connection with a former nursery on Freston Road that was built as part of Silchester Estate. This was handed over to Acava Studios and Latymer Projects as a temporary space for local artists prior to its redevelopment into More West. I made a film about the space and the 5 artists based here in its last days. I arranged for a local milk man to deliver one final crate. At 6am, in eerie darkness, I filmed him delivering his jinggling bottles. Then later on I improvised a sequence with other artists in which we walked around the nursery using these bottles as musical instruments and creating a trail of fragmentary glass. The nursery for children and artists had a special atmosphere. We were at home in its play spaces and rooms flooded by natural light. 8/10. More West was built on the site of my artists studio and the Nursery. It was an indicator of how the council wanted to replace social housing in the area by building around the high rise blocks. This must have also been part of the thinking behind the £10 million investment in Grenfell tower that was to follow. More West was Peabody housing for the 21st century: 112 flats with mixed social and market rent; £500,000 for a three bed flat and million pound penthouse pad on top, perhaps with a telescope trained down on its poor relations. Leo The Last meets J. G. Ballard’s High Rise. I tried to avoid my flat being used as a showroom by the developers and council. The architects model of the new housing block was on display next to a poster of the film Leo The Last. I would film spiders constructing their silky webs as builders climbed up and operated cranes. I got to know my immediate neighbours on the road who were waiting to move into More West. Some took this in a positive fashion, others clung to the memories of their former lives. The building was designed by Haworth Tomkins, complete with roof top sculpture that evokes Frestonia and has won many architectural awards. I have a soft spot for this building, but acknowledge it has yet to plant roots and be integrated with the high rise. 7/10. It is a building in need of love. Shalfleet Drive residents hand over keys to the developers, 18/01/15 More West (with crane in the centre) being built around Frinstead House on Silchester Estate View from the 17th floor of Grenfell Tower, 12/09/15 Building work collage: Frinstead, Markland, Dixon, Whitstable and Grenfell tower, 28/06/15 I wanted to conclude this blog by writing in detail about Grenfell Tower where I worked for one year four months. I was commissioned to made a film about the regenerated tower block and produce art for its new community room. I developed close friendships with residents. I don’t know how to evaluate the spirit of this building. It still pains me to talk about it in the past tense. As a postscript, let me branch out and offer a few comparative thoughts about the 1958 Notting Hill race riots and those tragic events at Grenfell Tower in 2017. Both shone a media spotlight on this area around Latimer Road station and exposed the deficiencies of society and council services. The chronic state of housing must have been a factor causing friction between white residents and the recently settled Afro-Caribbean community. Sociological studies took place into the root causes and how society could improve itself. In the immediate aftermath of both events, all manner of groups and social activists consolidated networks in the area to counter the lack of strategic guidance from the authorities. The Notting Hill carnival was one of the unexpected outcomes of the riot. What will follow the Grenfell Fire? I fear no positive outcomes in the short term. As of writing, the civil and criminal prosecutions are yet to unfold. There is great concern that the former will not address deeper underlying social issues and the latter will not result in anything other than corporate fines. It is a testing time to find spiritual qualities in housing and art. Burnt cladding in the garden of Lancaster West estate, 06/01/18

0 Comments

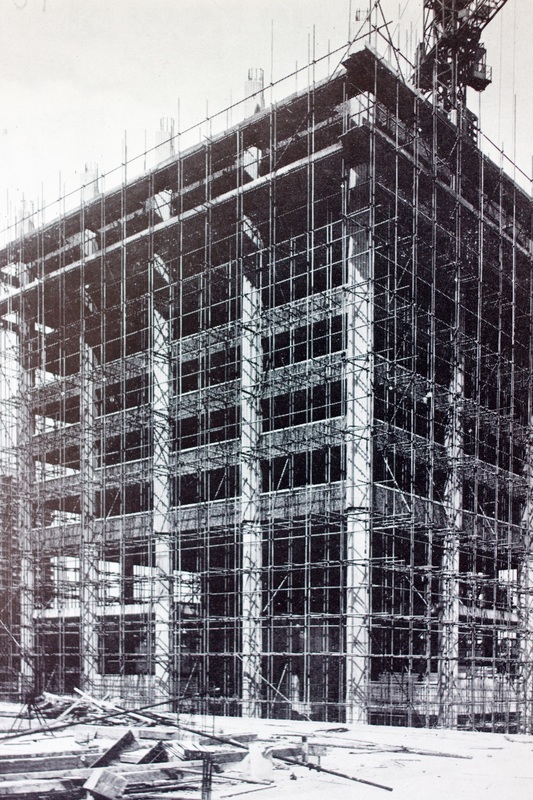

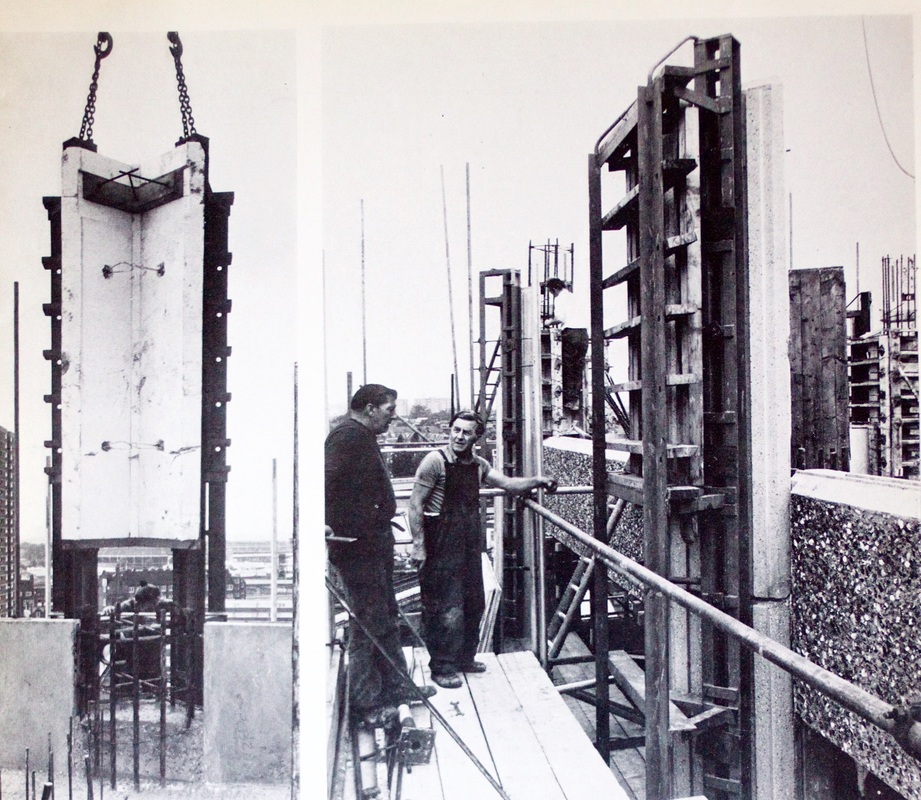

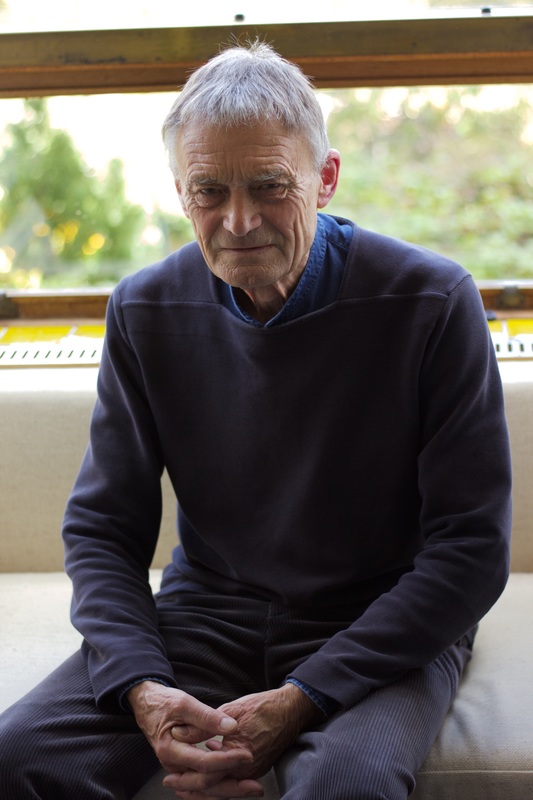

I've been working on Lancaster West estate for well over a year now. My commitment extended beyond the commission I had from the TMO (who manage the Royal Borough's housing stock) to make a mural for the new community room and a short film documenting the regeneration of Grenfell Tower. At the beginning, I was naturally regarded with a degree of skepticism. Why do we need an artist on the estate? But after attending numerous residents meetings and putting on art events in lift lobbies and during fun days, I earned my stripes in the community. During my tenure, I've had an opportunity to strike up many friendships across the estate. I offered them an accessible and sociable art. In return, several of them have entrusted me to render their remarkable life-affirming experiences and energising humour. More of these residents to follow. But first let's talk about regeneration and architecture and conclude by weaving both of these back into the beating heart and soul of Lancaster West. As of writing, Grenfell Tower improvement works is well nigh complete. After a £10 million regeneration, nine new flats have been created and offer affordable rents in an area where property prices average over £1 million and one bedroom flats on nearby More West are over £500,000. Each flat in Grenfell has had double glazing installed and a boiler for direct control of heating and hot water. The building has been thermally insulated with a new layer of cladding, although I miss the former design. The nursery and Dale boxing club also come back into vastly improved spaces and facilities. This upgrade to the fabric of a building is important in the context of how the council plan to regenerate this part of North Kensington. Silchester Estate, which is just across the road from Lancaster West, is currently being considered for regeneration. The initial options produced by the council were described as "nuclear" by estate residents. At a recent meeting in the town hall, several residents had the opportunity of making powerful statements to the council about the lack of consultation and the potential impacts of wholesale regeneration on the community and environment. The council listened and voted to explore the options in more detail. They also make a commitment to factor in the possibility of maintenance and infill. It is good to see how local residents are campaigning with a witty strap line (Gradual Change - In Due Course) that might have been culled from the insight of a former architect of Lancaster West, Derek Latham. He developed his ethos of urban renewal on a gradual basis after witnessing the impact of "slum clearance" in North Kensington during the 1960s and 70s. Previous blogs have featured interviews with Derek Latham and Peter Deakins, both of whom worked on the early stage design of Lancaster West estate. I can now present a complete documentary record of all the architects involved and their experiences, hopes and frustrations. One major issue was why the estate was never designed to its initial masterplan. This sense of fragmentation is perhaps the root cause for many of the challenges still being faced on the estate and which are being addressed by the newly formed Lancaster West Resident Association and the Grenfell Compact. I recently had the pleasure of meeting retired architect Nigel Whitbread and showed him around the estate. He lead the team who designed and built Grenfell Tower. It was the first time in over 40 years that he stepped foot inside the tower and enjoyed visiting a residents flat and those stunning views. What's interesting about Nigel's story is that he is a local boy through and through and not many local people seem to be aware of his role in the development of the area. We are also going to hear from Ken Price about the design of the finger blocks, the three low rise housing units that radiate out from Grenfell tower. Clifford Wearden is the design godfather of Lancaster West estate. I suspect his career path was adversely affected by the way the development panned out and not being the consultant responsible for all the later, much revised, stages. Chatting to his widow, Pauline Wearden, I was surprised to learn that, Clifford, like most other architects involved in the project disliked tower blocks. Grenfell tower was only included to maximise housing density levels; Nigel is an exception to this prickly high rise rule of thumb. This perhaps explains why Clifford in later life would drive over the elevated Westway and look across at the five tower blocks and declaim to his family that Grenfell tower exists no more and has been demolished for a new development. This is a poignant case of not wanting to see the concrete from the stone! Nigel Whitbread: I was born in Kenton near Harrow. My parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington. We moved as a family to this area in 1949 to be nearer the shop. I read quite recently Alan Johnson’s biography, This Boy. He is a Labour MP and former Home Secretary and interestingly was born in 1949. However his life and the poverty he lived through was in a different world, although just a mile away as the crow flies. He didn’t enjoy the family life that I enjoyed nor did he appear to enjoy his time at Sloane grammar school which I had done earlier. When I was going to leave Sloane, I didn’t know what I was going to do. One day I had an interview at an architect’s office. My eyes were opened. I liked the idea of drawing boards and doing something that I never understood to exist. The first firm that I worked for was Clifford Tee and Gale and that’s where I did my apprenticeship. I went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this I became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. I knew through delivering groceries that there was an architect who lived near my father’s shop. I told my parents this and my mother said she would speak to the wife of the architect who was also a partner in the practice. I went for an interview and got the job. This was at Douglas Stephen and Partners and this was probably the most influential time in my career. It was only a small practice but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that I worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. It was actually like going to a club and we were doing terrific work. Later on, I went to work with Clifford Wearden on Lancaster West. At that time his office was a two storey building in his back garden. It was a huge job for a small group. It was unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. Clifford was a serious architect but had a flair about him. He’d been in the Fleet Air Arm and had a lovely Alvis car which was a convertible as I recall. He did have a very bad habit whilst he was driving of turning his head and facing me whenever he was speaking which I always felt a bit disarming. I found this quirkiness an attractive aspect in somebody who was very precise in most things he did. The whole scheme had been well prepared and thought out by the time I joined to lead the team in designing the tower. The design is a very simple and straightforward concept. You have a central core containing the lift, staircase and the vertical risers for the services and then you have external perimeter columns. The services are connected to the central boiler and pump which powered the whole development and this is located in the basement of the tower block. This basement is about 4 meters deep and in addition has 2 meters of concrete at its base. This foundation holds up the tower block and in situ concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams all tie the building together. Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968, had been built like a pack of cards. Grenfell tower was a totally different form of construction and from what I can see could last another 100 years. Grenfell tower is a flexible building although designed for flats. You could take away all those internal partitions and open it up if that’s what you wanted to do in the future, This was unusual in terms of residential tower blocks. I also don’t know of any other council built tower block in London or anywhere else in England that also has the central core and six flats per floor rather than four flats which is typically done on the London County Council or Greater London Council plans. We were wanting to put our own identity on this. The GLC built Silchester estate and I had nothing against that but this was so different in many ways. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, we thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. We used insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, lifted up and put into place with cranes and they were so much more quicker. In an architects mind, they want towers to be an elegant form rather than stumpy. This was a challenge and was why I introduced as many vertical elements within the fenestration as I could. The only thing I could play with was the windows and the infill between the windows. I treated it like a curtain wall, to get the rhythm of a curtain wall. We lost some of this verticality in the recent re-cladding but it’s not the end of the world. And the building is now better insulated as we had different standards then. The floor plans were based on Parker Morris Standards which they used at that time and sadly have gone now. These were very good standards for storage and the way furniture had to be included in the plans. It was delightful to hear that residents thought flat arrangements worked well and I saw the views recently which I always thought were terrific. I wouldn’t have minded living in a tower block myself. Tower blocks were criticized for not being suited to people or a lot of families were being forced into it and they were feeling more and more remote from the street and meeting other people. But there is another side to this and it always seemed to me that if American’s can live in tower blocks, why can’t the English? This is the first and only tower block I designed. This was also the first social housing I ever worked on. No social housing has been built since this and I’m very much against knocking things down unnecessarily. I had heard that there had been problems a few years ago with the heating and it was no good and talk of the whole block having to come down. And I thought, if my heating goes wrong, I don’t want to pull my house down. It’s a great shame that the basic concept for the whole of Lancaster West to have a first floor deck for people, shops and offices and parking underneath wasn’t seen through for whatever reason. This means that there remains a basic flaw. Clifford Wearden and Associates only built Stage 1 and the remaining parts were built by other architects. I don’t think the designers are to blame because there was a requirement that it was designed to have cars for every flat. We’ve all seen things have changed dramatically since then and now cars can’t be accommodated everywhere. After Clifford Wearden, I worked for Aukett Associates and I was there for 30 years until retirement. Recently I’ve become involved with my local residents association and committees in drawing up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan. We included the Imperial West site over in Hammersmith and Fulham because that was already impacting on our conservation area. Hammersmith wouldn’t agree to this but we continued developing the plans liasing with RBKC and residents. The Neighbourhood Plan includes objectives around shopping, housing, offices and conservation. We have also identified 3 existing unbuilt spaces which are now designated as local green space and cannot be built on. Latimer Road is included in the plan and we think that could be redeveloped to improve the area and have more housing put on top of the business units. We have to have housing somewhere. That’s where you could do it. But don’t build on our green spaces. The Localism Act which the Conservative government introduced is a very powerful tool actually. Residents are able to influence the way their area is developed. Ken Price was lead architect responsible for the team who designed and built the finger block units (Testerton, Barandon and Hurstway) which formed stage 1 of the building project. Ken Price: My origins are in Derby in the Midlands. I went to the School of Architecture in Nottingham which at that that time was part of the college of art and is now part of the university. I worked for a short time in Derby and then I was offered a job to work in North Africa in Tunisia. I went there for 3-4 years. I came back and worked in Nottingham for a while with some ex-students who had set up practice there and and then changed jobs in and around London. After Lancaster West, I worked with Casson Conder partnership and was job architect on the Ismaili Centre in South Kensington. Subsequently I set up my on my own and did small scale projects, mostly interior work and retired a few years ago. Clifford Wearden won the Lancaster Road West development in Kensington. After a bit of a hiatus, the commission was confirmed for what was called stage one and he asked me to go and lead the team as project architect for the finger blocks. I worked for him and Kensington and Chelsea to develop the original masterplan which predecessors had worked on. Clifford was extremely good at handing over and saying - look this is the problem, you solve it and refer to me if there is still a problem. He was very generous although he had the overall view and concept. I know that he was very sad that the development became a little bit like the Barbican. It was a grander scheme and there could well have been more productive elements which just didn’t arise. I wasn't involved in those preliminary stages of development, so I can’t speak too much about how that evolved. But I was aware that the Silchester Baths on the site became listed and affected the masterplan. I briefly saw the housing in the area before or after it was all painted white because there was the famous or infamous film, Leo the Last. Was it black or white? Why did I think it was painted white. The director was John Boorman. I think I must have seen it just before they did that and probably immediately after. After it was cleared there was no real evidence of life or to how it was. I don’t even know what the state of the dwellings were like and whether they were totally without facilities. At that time there were a number of schemes underway to deal with the housing issue, alongside the problem of car ownership .One could describe it as the deck system when cars were kept down below and freeing up the ground level or the raised ground level for pedestrian use and housing. It was part of the brief to provide that amount of parking and it did subsidise some of the other elements. My predecessor had sketched in a basic outline of the finger blocks. I took that on and developed up the detail of the individual housing units and the spaces between. I suppose we were interested in the intricacies of locking together volumes of accommodation in order to maximise the space of each dwelling. Also providing, to a degree, some private outside balcony or roof terrace on the top areas so there was an opportunity for people to have their own little bit of outside space as well as the bigger outside. I still have a small model of the finger block that was made by a friend of mine, a model maker. It shows the different accommodation elements by colouring. It was really a demonstration to the council on the mix of the different elements. Community garden between Barandon and Testerton Walk. A constant source of artistic inspiration for Constantine Gras and featuring as the backdrop for several of his films: Vision of Paradise. The landscaping was dealt with by Michael Brown (landscape architect, 1923-1996). Clifford was very determined to ensure that the landscape was taken on and he persuaded RBKC to employ him. I think one of the essential elements in the concept was this endeavour to provide as much open green space as possible by concentrating the housing units. The density was probably what was expected or required by local authorities at that time. The estate was designed to try and retain that as much as possible and the tower blocks were an element in that because you’ve got a concentrated stacking of accommodation which again added to the freeing up of groundscape. Although there were a number of tower blocks around at Silchester I don’t think any of us would have chosen to have incorporated the tower block but it must have contributed to this density issue and freed up the amount of green space that was enabled. I think the estate was built to a good standard. We persuaded a brick manufacturer called Ockley to make bricks especially for the estate which weren’t available. It was just at the start of the introduction of metrication and it seemed to me, in particular, that it would be rather nice to make life easier in measurement terms to have bricks that fitted the metric. So they are specially made, 30 centimetre long bricks. We wanted to use brick as the main element in order to connect perhaps with the past more than you would have done with clip on panels. It does survive time rather better than a lot of materials. I still imagine they look pretty good. They were very nice brick manufacturers. I knew there was a hiccup in the construction process but I couldn’t quite remember what it was. (The contractor, A.E.Symns went into receivership in 1975 at the very end of the construction of phase one). I can’t think of a building site where that didn’t arise especially as the construction was over such a long period. There were industrial dispute problems (three day working week and building strike), but not hugely disruptive as far as I can remember. In those days it was very difficult to get contractors to keep the site clean. Now because of health and safety issues, I think building sites are much better managed. It’s a shame they never built the planned shopping centre or offices. There was an expectation of community facilities including commerce and everything else in order to make the place work. I don’t think there were any warnings flagged up that there might be vandalism. It certainly wasn’t in evidence as it was completed. I visited after it was fully occupied and there didn’t seem to be any evidence of vandalism then. We never got any feedback as a practice on you should’t have done this or that. Perhaps we could have foreseen some of the possible problems. At the time disability access wasn’t an issue. It should have been but it wasn’t. Now that wouldn’t be allowed. You have to provide much more facilities. Unless the facilities are provided people will abuse what’s there and definitely need alternatives. Maintenance has been the problem in almost every area of social housing that was built at that time and subsequently. it’s one thing to realise and provide housing for umpteen people, but then to not maintain the estates or keep them going. It was very short sighted. That’s why social authority housing has all but disappeared because nobody is prepared to take on the long term issues. It was a product of its time in the way it dealt with a big housing issue, sub-standard housing. And hoping to provide the mix of urban renewal, accommodation, green spaces for enjoyment, kids playing and all the rest. This was just one of a number of schemes which were resolved in different ways but the deck idea was a sort of constant thing throughout. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Estate, which is due for demolition now, was one of the background influences on the concept of Lancaster West. There was also a reference perhaps to the Lillington Gardens estate just off Vauxhall Bridge Road. That’s a famous development by Darbourne and Darke which I think still survives very well. Ideas of large scale redevelopment and housing tend to go through different phases of acceptability or relevance and it’s very difficult to look back and say that was the right decision to make. In some cases it was the only option either because of financing or government pressure or politics. But I would have thought that if the masterplan was completed it would have provided a better result than has eventually arisen. But it’s very difficult in hindsight ever to say. Pauline Wearden whose husband was the lead architect for Lancaster West estate masterplan and building stage 1. Pauline Wearden: Clifford was born in Preston, Lancashire in 1920 to working class parents. His father was a plumber and his mother was in retail with a profitable cafe. Clifford was his mother’s golden boy and she paid for him to go to university. There were no architects in the family. It just came thorough Clifford. Clifford studied architecture at the University of Liverpool from 1938-40 and 1946-48. He was very fortunate because that was a prestigious university in those days turning out many famous architects and Rhode Scholars. When war broke out, he immediately volunteered. He had a lovely war, mostly cocktail parties. No. No, He did have a lot of tragedy and he saw his best friend shot down. Clifford was a pilot in Air Command. He had travelled as a student on what they call the Tour and he’d been to all the classic places but during the war he also saw some exotic places. From 1949-54, Clifford was chief-partner for Sir Basil Spence. This was when they got the commission for rebuilding Coventry Cathedral and Clifford was given the job of preserving the ruins. He was very proud of that. I don’t know what brought him to London. But he had no home and went to International House Hostel. He lived in a hostel for years. He didn’t have anywhere stable until he bought his top-floor flat in Argyll Road, Kensington. Then he came across this derelict house on Homer Street, Marylebone. They were a row of 6 Georgian houses in that street and the property owner wanted him to do up the other houses as well. So he worked on those and then bought one of them. That was probably one of of his first jobs alone. By the time I came on the scene in 1965, Peter Deakin was there and Derek Latham was a student. Clifford built an office at the back of the house. A very nice studio designed by him which was contemporary which might have looked strange at the back of a Georgian house. This is where the master plan for Lancaster West was prepared. Eventually the practice had to relocate premises as there were twelve in number. It was like I married twelve men because they were always in our house. Clifford came home one day and he said they are blowing up one of the houses in North Kensington. And we said - what! And he took us all in the car at night. The director was just about to film the house being set on fire and demolished. They had all the safety people and security and police vans. We had to creep through the security set up. Nobody had invited us but we said we wanted to see it. They had built a false house to make a cul de sac and when you looked it was completely false, but it didn’t look it. So we were exactly there for the big bang. The children were thrilled. I can remember seeing big cameras, arc lights, just like you dream for an outdoor film set in the dark. It was typical of Clifford to have the children up. He didn’t want them to miss anything. However, I don’t think Clifford ever saw the finished film, Leo the Last. He wasn’t particularly interested in films. Lancaster West was his first very big job. But he got into the mould very easily. He more or less expected it working with Sir Basil Spence and being up there with all the old Liverpool people. He was very much an architect’s architect and he felt that his time was coming. Some architects don’t like meeting their public, but he was very good at that. I think he listened to them. One of his ethos things at university was social housing. So he felt very strongly about it. Of course, affordable housing it’s called now. I think he’d be absolutely disgraced by some of the policies such as right to buy. However, I don’t think he was a socialist. I don’t even know his politics but he was fairly traditional in many ways. We married in 1969 and you took over your husband’s life or it took over you. He was doing very well in 1969 but of course it’s a hand to mouth existence. Your only as good as your next job and the 70s were quite stressful and then in the 80’s the work fell away. We had to economise and got rid of a car. We were trying to think of other ways to save money. It’s very difficult when you’ve been having a certain lifestyle and it worried him terribly. He used to worry about what might happen and I always felt that was a terrific waste of time. He lost quite a lot of sleep over some jobs. Clifford believed that the tower block at Lancaster West was demolished. We drove past it on the Westway. He said it’s no more. And I remember saying to him, that we should have gone to see it come down. In the family we all thought it had gone but one day my son said it was still there. I think he would have been relieved, quite honestly, if it came down. He didn’t want it built. He didn’t want to be in this era of tower blocks. He felt very strongly about vertical living. It wasn’t right. So I don’t think he took any pride in it, except that it was not a bad building and it did work. I’ve never really appreciated that Lancaster West was landscaped or intended to be. In the model of the estate that my son has hanging from the wall in his house, there are little trees made by Ken Price. And they always put trees in as their panacea for making it look homely. But it did look good in the end and not as desolate as it might have been. I’m afraid to say that driving past on the Westway is the nearest I’ve ever got to seeing the estate. I’ll have to go. The best way is to walk around, I imagine. I'm going to end this essay with a few extracts from residents who live on Lancaster West estate. We are not now talking about perspectives and plans or so many housing units that can be redeveloped. We are talking about homes. People who have planted roots, raised their family and want to retire with peace and dignity. These flats and houses that were designed and built in the 1960s and 70s are now home to a diverse range of people who want to live in one of the richest boroughs in the universe. They deserve to have the final word. One hopes that in 10 or 20 or 40 years time, that they are still living in the area, as the new kids on the block are contemplating how to buy into the next cycle of housing redevelopment. Christine Richer, resident of Hurstway Walk: My mother was an African-Welsh woman and my father was black African American. They met after the war in the West End. Two weeks after my 18th birthday, I came to London and I landed in St Stephen’s Gardens in North Kensington. Massive, one room bedsit with the kitchen in the corner and the mice. The mice were hell. That was my first living in a big city. I came to the estate in the 70’s. Funny story. The first day I came here to meet the electrician and the gas people. No one turned up. I end up sleeping on the floor. And I had the most vivid dream of my life. I wake up in this dream watching my coffin being carried down the stairs. I saw these two shapes and they were my daughters. But it was very pleasant. I thought this is my place. My place on earth. I’ll live here till I die. As a child, I moved a lot. In Grenfell Tower there was a really nice club, like a residents social club and my partner at the time was on the Committee. That was my first introduction to the estate. It was full of different people who knew each other from the neighbourhood: Moroccans, Africans, blacks, whites, Portuguese, Spanish. I think with my involvement in the resident association and Estate Management Board, when the children were young, they have learnt a sense of community. They would always come and help me if I say I’m doing something with the R.A. Volunteer themselves, wash dishes. The garden down there was very important to me and the kids. They spent their formative years down there with or without me. We had family parties, barbecues. That living space outside there meant a lot to me. I do believe that we are going to get knocked down as all this gentrification is happening all around us. And we are not a Victorian block which is a beautiful thing. We are a 1970s fling them up, fling them down block. I don’t know where I’ll end up. That’s the biggest concern for me. That makes me stay awake at night. That makes me cry. If they could build another block, 4 or 5 streets away, where I knew I was going to be rehoused. It could be Manchester. All my close friends who live on the estate, only about 3 are here. Everyone’s gone. It’s a changed community. I haven’t always loved all the neighbours. But the neighbours that I have liked and I’ve made friends with, we’ve loved living here. The old families who brought up their kids and their kids have grown up and moved away. It’s been a home to a lot of people. Edward Daffarn, resident of Grenfell Tower: I’ve lived in Grenfell Tower for over 15 years now but I’ve lived in North Kensington, Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill Gate, my whole life. I found education was quite a therapy. I became a social worker for about 7 years. And then sadly my mum, got motor neuron. so I gave up work to look after her. I haven’t got back into social work. But what I have got involved with is housing issues on Lancaster West and in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The stuff that we’ve been doing on Lancaster West started as a result of the Academy being imposed which was 5-6 years ago. When we first started there was virtually no community groups around. Five years later there's a lot of community activism because of what’s been happening in housing. Westway 23, Focus E15 Mothers, The Guinness Trust down in Brixton, Our West Hendon, Sweets Way and all the radical housing network. There’s all these different struggles. On the 24th June, this year, 2015, the council passed a motion in the full council meeting saying that they were going to go ahead with the destruction of all low density social housing in North Kensington. Low density means this, They’ve been built nicely, giving people some space inside and with some green residential amenity outside. Trees and green space for their children to play in. Low density housing. It’s not anything else. It’s just nice estates. It will be interesting to see what will happen to Silchester. Because sooner or later, one community is going to say, and it only needs one or two inside that community to lead the rest - just to say - your going to knock our houses down - oh yeah! Oh yeah! Let’s see about that. North Kensington has a good history of not just taking these things lying down and when people finally wake up and realise what is going on, maybe the council will get a bit of a shock. They call Lancaster West the forgotten estate. And it hasn’t been called the forgotten estate for the last couple of years. It’s been called the forgotten estate ever since I’ve been on here. If it had been maintained properly, Grenfell Tower and the finger blocks are quite beautiful. Particularly if you live here. I don’t know the architect that designed them but they have architectural merit. I don’t know how you say you love your home. You love your home. If we remember what happened in 1974-75 by the signs, Get us Out Of this Hell, then maybe the Grenfell Action Group blog, the protest that we did going up to Holland Park Opera, the procession of Westway 23 along the Westway, will be things that in 25 or 30 years, people would look back and say, when they took away the stables, the Westway Stables, when they took away the children’s centre, didn’t people say anything. And they get on the computer. Look I found this Grenfell Action Group. Yeah they did something, And they did this demo. That will inspire the next generation of people who would care about their community. Clare Dewing, resident of Talbot Grove House: My parents were squatting in and around the area. Mum became pregnant with me and said right Paul, get us a flat now. My first steps were actually in the flat that I live in right now which I share with my mum. When my mum walked into an empty house, she put me down. I stood up and apparently I ran just clean straight across the room and those were my first ever steps. Growing up on the estate, we were told never to leave the estate because I’ve always viewed the estate as two halves. My half which is Talbot Grove house, Verity Close and the other half, the finger blocks and Grenfell. So when we were a bit naughty, we used to go on the other half and do knock down ginger and stuff like that. I did probably knock on Christine’s door. About 1993-4, I was quite naughty and I’d be going to clubs, sneaking out. Mum and Dad wouldn’t know and my friend would say she’s staying at my house and I’d say she was staying at her house. Teenagers you know. I do remember it being quite scary trying to sneak back into Ladbroke Grove and we got mugged a couple of times, got followed a couple of times. But in recent years, I do feel the safety has improved. There used to be crackheads on every corner, all along Portobello. But that kind of edginess gave it a vibrancy which unfortunately, I think, it’s almost gone. About 5 years ago unfortunately my dad became ill and I moved back to my parents house to look after my dad. We’d always known that my mum’s memory wasn’t too good. But it was only after my dad died that we managed to get her to have a full proper diagnosis that it was early on-set dementia. Mum’s going well. I think the progression of her dementia has slowed and I think that’s down to a combination of exercise, good food, good stimulation. I wanted to join the R.A. because it got me to kind of flex my muscles again in using organisational skills in a different way and and just giving back to the community that’s helped me out so much over these last few years. Kensington and Chelsea are an amazing borough to live in especially the way that they look after the older population. I also had a bout of depression as well and the services that were available to me are not available to some of the people that I’ve spoken to. So I feel that the support is there and that’s why I’m really surprised about the state of the housing here. It doesn’t marry with my experience of all these other services. I think Kensington and Chelsea need to be aware that if they just sell all the properties off and make it into a million plus houses, that what draws people here, what draws people to Notting Hill, what draws people to Portobello, would just be gone. It is that mix of culture that drew people here in the first place. That made it trendy. That made it hip and cool to hang out on an evening. It’s just going to turn into Kensington High Street and be replaced by Cafe Nero’s and shoe shops and places you can’t actually afford to shop in or buy food in. What we are trying to do as a RA here is to lay the foundations now. We're trying to get ourselves prepared and ready so that when the regeneration does come that we are ready and we've got some ideas together. Hopefully we can influence them which would be great. The entrance to the Architecture Gallery at the V&A has a classic marble staircase. It echoes to the sound of history. On the 19th and 20th November 2014, I held a film screening and paper folding workshop here. Visitors approaching the space would have heard the following sounds and voices. Fragment 1 The sound of WW2 bombing, glass shattering and the percussive dub of the Notting Hill Carnival. This reverberation in a usually quiet location caused a few raised eyebrows and the volume had to be scaled down. Fragment 2 North Kensington residents reminiscing about good and bad days, post-war poverty, multicultural experiences, poor housing and the British sense of humour. An American who lives in London and who viewed this section of the film programme commented about the shocking poverty and how in the good U.S. we never had it so bad. Fragment 3 A filmed conversation with Joanna Sutherland, project architect at More West housing development. This is where I am based as V&A Community artist. She talked about: "What we are seeing ... is the threat to communities due to the expense of living, not just in central London, but all areas of London. I think there has been a growing interest in the last ten years, if not longer, of how communities evolve and what's important within a community, whether it's through schools, a community facility, a church. And I hope that this project, Silchester and the wider area, still remains a home for those who have lived there, had children, and maybe they can continue to live in the same place." It was heartening to hear positive comments about this film from residents of the estate currently undergoing transformation. A new community is forming at More West built on the foundations of the previous slum clearance redevelopment in the 1960s. That phase of development was very disruptive coupled as it was with the building of the adjacent Westway A40. It did however create social housing. Today, there is no longer a desire to match that social vision, and what is affordable in terms of rent and quality of life, is beyond the means of many. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and Peabody are providing part social and market housing at More West that consists of 45 rented homes, 39 shared-ownership and 28 for outright sale. The new housing is part of a rapidly changing area. However as our local councillor states: "There are too many poor people." Councillor Judith Blakeman has to deal with many of their social problems. Fragment 4 Glockenspiel and assorted drum kits provide a positive vision of the future. Children from Frinstead House are drawing. A girl illustrates herself waving goodbye to her father from the 20th floor of the high rise; he is waiting for his train at Latimer Road tube station. Another child mischievously draws a giant t-rex attacking the tube station. This is regeneration, disaster monster movie style. Yet another child provides a rainbow arcing across the skyline. This was one of my most direct and rewarding engagements as community artist. I did not advertise this. I merely set up a large sheet of paper in the foyer of Frinstead House and invited local residents to accompany me in filling the blank. Adults and children confirmed their cultural identity and what it means to live in their high rise homes. Fragment 5 - Was not heard at the museum. It has not been caught on camera or in any of my expressionistic documentary work. I hope to render this shortly. Symbolised by a DJ playing at a recent marketing event for More West. He has bought a flat and will move to the area in 2015. He is excited. Young and professional. For him there is no lingering doubts. He is forging the future in progressive sound waves. Zeitgeist. In summary, this curated programme had the aim of dialectical montage, the juxtaposition of contrasting images and sounds. This is our experience in all its complicated social modes. It is both beautiful and ugly. We build for the future and paper over the cracks. Speaking of paper (workshop), I have also provided a visual record of how young and old came together at the V&A Museum. Complete strangers who with a little encouragement and artistic structure are able to express light and shade, twisting new shapes into being and creating another fragment (like no 4 above) that brings a smile to my face. Outside the builders are laying bricks and installing windows. In my studio all is calm. I've been in listening mode and am currently transcribing two audio interviews.

The first was with Joanna Sutherland, Associate Director at Haworth Tompkins and project manager for More West housing development. It's fascinating to hear her talk about the visual appearance of the building taking shape opposite Latimer Road station. She explained the significance of a special Dutch brick called Bronze Grun. "The appearance of the brick, the tonal variation across the brick and the right mortar colour are absolutely crucial to the success of the project." It was not however easy to replicate trial samples and meet the original planning requirements. "We were in no way going to allow anything to go through that wasn't perfect. And if you look at mortars, different mortars of brick, it completely changes the appearance of the brick. So even now when you still see the area that has got the salmon pink, you can see it's a nice brick, but it doesn't look very good. And where the mortar's right, it looks fantastic." My second interview was with Terry Bloxham, Assistant Curator for Ceramics and Glass and the V&A. She gave me a superb tour of stain glass from the medieval period to the present day. This provided context on a Nathaniel Westlake panel, The Vision of Beatrice, that I'm using as inspiration for my project designs. "Westlake is the culmination of the Gothic revival. Of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval artist." "In the panel we've got little pieces of glass, careful chosen. It's not just take that one and put it there to make the picture. But to get the right balance of light coming through, maybe the ones on the bottom are thicker, thinner at the top. Before you put it all together in the lead framework, other techniques are used, like painting, and staining and etching." The Vision of Beatrice illustrates a scene from Dante's Divine Comedy. This is the climatic moment when Dante's love has become divine and he can be transported from purgatory into heaven. Recently, I met buyers of one and two bedroom flats at the development. Young professional workers who were excited about moving into the area. They wanted to know about local facilities and views from their flat. I could comment on the former. Hopefully they were pleasantly surprised to hear about the the complex social history of the area and having the Notting Hill Carnival right on their doorstep. I wonder if they will experience divine love (or otherwise) in their homes. Let us hope so. Future artists and historians will interpret and tell a story. In time. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed