|

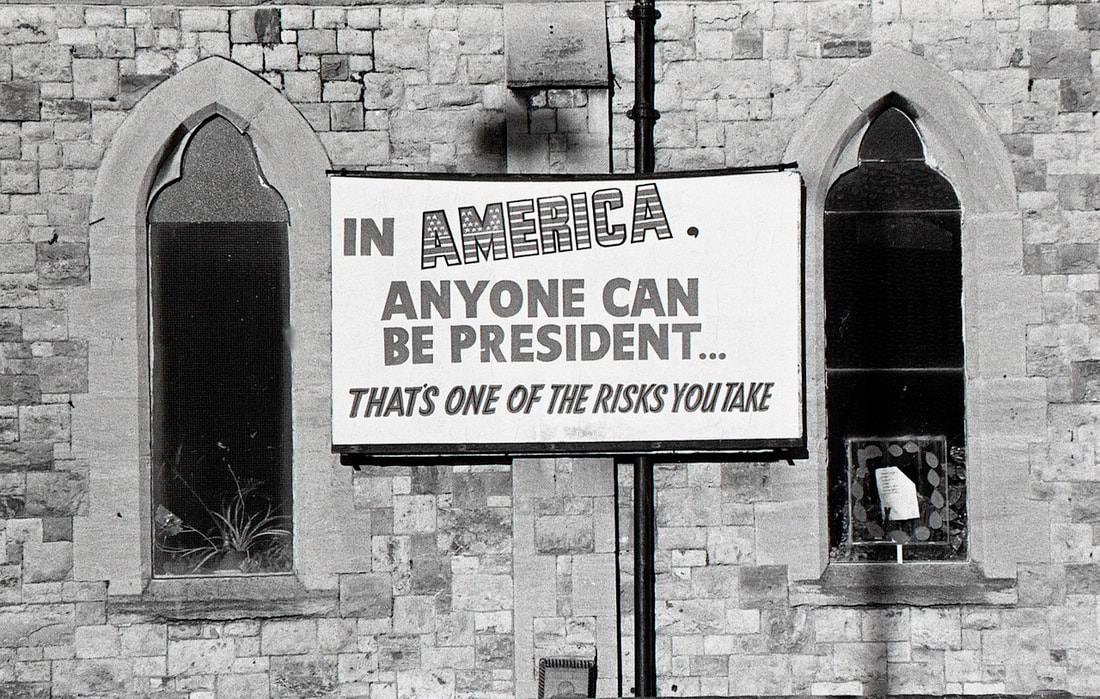

A year begins with John Whelan (pictured above) and myself sketching out a project plan and ends with an accumulation of Chaplin books: most of the pages well thumbed and words digested; some semblance of meaning extracted for artful purposes. But for a long period of time, I subscribed to the view that Buster Keaton out-classed Charlie. There is still a snobbish tendency to belittle the "Little Fellow," regarding his playful anarchy as a mere slap and dash; although, fair to say, this primal quality holds true to the early Keystone films. Funding permitting, a major arts project in 2019 will redress this balance and more. John and I want to commission ten artists, all working in different media, to explore the contemporary relevance of Chaplin's life, politics and films; rooting this in the community context of Lambeth and Southwark where he was born and bred. Imagine a month long festival of Chaplin-inspired art! We want to build on the Arts Council funded, The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle (2017), where we imagined Chaplin meeting Michael Caine outside the Coronet Theatre in the Elephant and Castle. Reading The Tramp's Odyssey, I was particularly moved by an interview Chaplin gave to a journalist from the New York Times in 1920. Chaplin was by this stage a global film star. His iconic image had evolved from the Satyric drunk into a rounded character who could command the high notes of comedy and the lows of pathos. The Kid in all its majesty was around the corner, arguably his first masterpiece. Chaplin had also become mega-wealthy and powerful, calling all the creative shots in his own studio. But only a few years before he was a struggling performer on the stage, having endured the hardships of childhood in slum-torn Walworth and Kennington. Chaplin's parents were both music hall performers: his alcoholic father had abandoned the domestic life; his mother would suffer from psychosis. With no parents to look after Charlie and his brother Sydney, they both spent time in the workhouse. In the interview, Chaplin recounts Christmas as a seven year old at the Central London District School for Paupers. Presents were being lined up on a table for the young inmates: tin watches, bags of candy, picture books. Chaplin had his eye on one particular object, a "big fat red apple". He had never seen such a beautiful fruit before and perhaps was motivated by a hunger that the institutionalised food could not meat/meet. When he was approaching the front of the queue, an elder pushed him out of the line and took him back to his room. Chaplin was haunted by these brutal words: "No Christmas present for you this year, Charlie - you keep the other boys awake by telling pirate stories." As it's the season of goodwill, let us rewrite history and surround Chaplin with apples and exotic fruits galore. The photo above shows the seven-year-old Chaplin (middle centre, leaning slightly) at the Central London District School for paupers, 1897. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons. What were those pirate stories Chaplin told his peers and which got up the snooty noses of the authorities? We can visualise him acting out cut-throat characters, obsessed by trinkets of gold. Perhaps this play had an element of the outsider, the Tramp that was to be. I am also paying my own black and white homage to Chaplin with the following series of photos. Fade in to the Church on the High Street, Willesden, the year of the Second Millennium. A cleric is fighting a losing battle to the world outside but maintains his sense of humour. The Tramp wanders into shot with a new bowler hat, baggy trousers and overripe boots that was bequeathed to him down at the Clothes Bank. He is seated on the wall oblivious to the sign above his head. He tries to make eye and smile contact with each passer by. They avoid him like the plague. The Tramp suddenly screams in silence. There is an attack in his jacket breast pocket. A circus of fleas from the previous owner of the suit? No! He pulls out a....... The title card reveals it is merely the ringtone of a new fangled mobile phone. Welcome to the year of Chaplin, 2019.

2 Comments

In December of last year, I made a pilgrimage to the garden at Lancaster West Estate and ended up with a vision for a dance at Silchester. While we didn't quite manage a waltz during Art For Silchester there was a performance and musical element to our drawing and ceramic making with over 200 local residents taking part. A special atmosphere was conjured. We shared life experiences and humour over the soundtrack of our own studio musicians. All the amazing art work went on display at Estate Open Weekend and also toured down to the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith as part of a fundraising evening for Grenfell. Many thanks to Nahid Ashby and London Funders for supporting my residency which acted as an informal therapy for affected residents to mitigate recovery from trauma. And also to RBKC Arts for the funding of book making workshops in early 2019 that will produce 60 copies for residents. I have long been championing creativity down at Silchester and look forward to SPID Theatre Company joining us for more artistic happenings. What of the garden? The garden in the shadow of Grenfell that I have been visiting for the past five years. This patch of humble green in the middle of Testerton and Barandon walkways has featured in two of my previous films, Vision of Paradise (2015) and The Forgotten Estate (2016). I continued my vigil here over the course of 2018 shooting a film which is in the final cut. The film is about Stewart Wallace and my spiritual connection to his garden in the aftermath of the fire that claimed the lives of 72 people. The garden was partially damaged and the soil contaminated. But life continues. The Strawberries Are For The Future will be released in 2019. This week I went on a walk to All Saint's Notting Hill attempting to reconstruct a photo that was taken circa 1850's. Is this the architect and assistant posing in front of the church in a landscape of mud? They look at us and the uncertain future of urbanisation. The building works had ground to a halt. The church had run out of funds and the spire was never built. What we see in the contemporary photo is the restored building after extensive WW2 bomb damage. Buildings invariably tell a more dramatic story than a garden. I recall how in 2015 the original architects of Grenfell tower met residents and listened to their experiences of living in the high rise: positive in terms of flat size and the views; although they registered the impact of the renovation taking place. I took photos of three of the architects around the estate and one posed by the new sculpture at the base of the building that was being wrapped in flammable Reynobond polyethylene (PE) cladding panels. I still have no consoling memory of these social decisions I made as an artist, in the humane intention to forge links between the past and the present that was on the brink of destruction. But still I walk albeit with a limp of late (ankle injury healing). Maybe it is not the end destination that matters. En route to All Saint's, I walk past the Portobello Wall Public Art having completely forgotten about this commission. This is a 100 metre length drawing into paint by Anastasia Russa. It is a kaleidoscopic image of local folklore that also takes in the recent tragedy of Grenfell. It will be an impressive specatcle when completed; assuming more work will be done to colour in the graphic outlines. As you approach the wall from Goldborne Road, the first portrait you encounter is Piers Thompson. Most appropriately, Tim Burke can be found at the other end of the road, near the Westway. Piers is a resident of Silchester who campaigned to save the estate when it was (still is!) threatened with redevelopment. I smile at how Piers wittily adapted one of the lines from the architects: "What do we want? Gradual change. When do we want it? In due course." Mr P is also a hipster DJ and hosts the Portobello radio show. A man who seemingly knows everyone and is forever making meaningful connections. Tim Burke, I regret to say, was prematurely taken from us this year. I have fond memories of his support for my first film, Floodlight (2010); it was screened at the pop up cinema that he set up under the Westway. We swapped Ballardian notes on the Westway and he paid for me to make a short film that involved a taxi ride across the elevated road. In between Piers and Tim, there is an array of characters and situations, real and imagined, with perhaps too heavy a dose on historicism. But being a hat fetishist, I approved of all the flat caps and trilbys and straw hats. But is this relevant to our contemporary world? As if by creative calling, a man passed that moment and asked me if I knew who I was photographing. He introduced himself as Paul and invited me to look at the painting of Leslie Palmer which was sited at the another end of the wall. We trotted up. I only knew Leslie by name and deed; he is a founding figure of the Carnival. It was a pleasure to make the connection and have him talked about so affectionately by a friend. Also included in the narrative is Khadija Saye. I never met her in the year I worked at Grenfell tower as artist in residence. She died at a point when her photography was on the brink of wider acclaim. Let us hope that one day a proper retrospective can be held to celebrate her talent in the local area rather than down at the Tate's of the world. So pausing, perusing at the wall, I ask: what is this representation of past, present and future? Whose history? As an artist who often mines the deep resources of personal and collective history, this can be a thorny process. How do you represent and edit? It's well documented that North Ken has a complex and troubled history: deep social divisions amplified by a discredited local authority and a governing class that has recently imposed austerity cuts affecting those most in need or vulnerable. Even at the grass roots level, an organisation which was set up to manage 23 acres of land for the benefit of the community, has had a checkered history. Most recently, with its own corporate-lead redevelopment plans that were halted by fierce local criticism. Toby Laurent Belson and Niles Hailstones, artist and activists, have been leading the fight against the Westway Trust to be more inclusive and accountable. The Tutu Foundation is running an independent review into Institutional Racism covering it's practices and policies. This is part of the unfolding history and artists play a role in not only providing cohesion and well being (what our funders want), but the need, when required, to thrown down the gauntlet and challenge the status quo. We wait to see how the Portobello Wall art panel unfolds. It could do with some explanatory sections; perhaps our local historian, Tom Vague, will be busy over the summer with guided walks. Will the community get involved, colour in and add their own experiences? Can it fully capture the rich radicalism of the area? Hopefully Anastasia is up to the challenge. And we want to see her tell the story (she has already started) of 13 members of a local monkey jazz band (yes, I said, monkey jazz band!) who escaped from their owner, with several holed up at Latimer Road station, pelting passers by with bananas. Nuts! I have an uplifting update on that blog from last year. I talked about how I and my film/art was in a state of suspended tension. During the course of last year, it's been a privilege to be a small part of Grenfell United and specifically to support residents from the tower in any meaningful way in rebuilding their lives. This has involved supplying several with art work, photos and film footage of loved ones and the community that lived at Grenfell. And the art work made during the Grenfell Fun Day? It is now hanging in the community rooms used by Grenfell United and a copy had been presented to The Speaker, The Right Honourable John Bercow and is part of the parliamentary art collection. A special mention to Nendie Pinto-Duschinsky for organising the art presentation and for marshalling the volunteers who supported a day of campaigning by the survivors and bereaved family members.

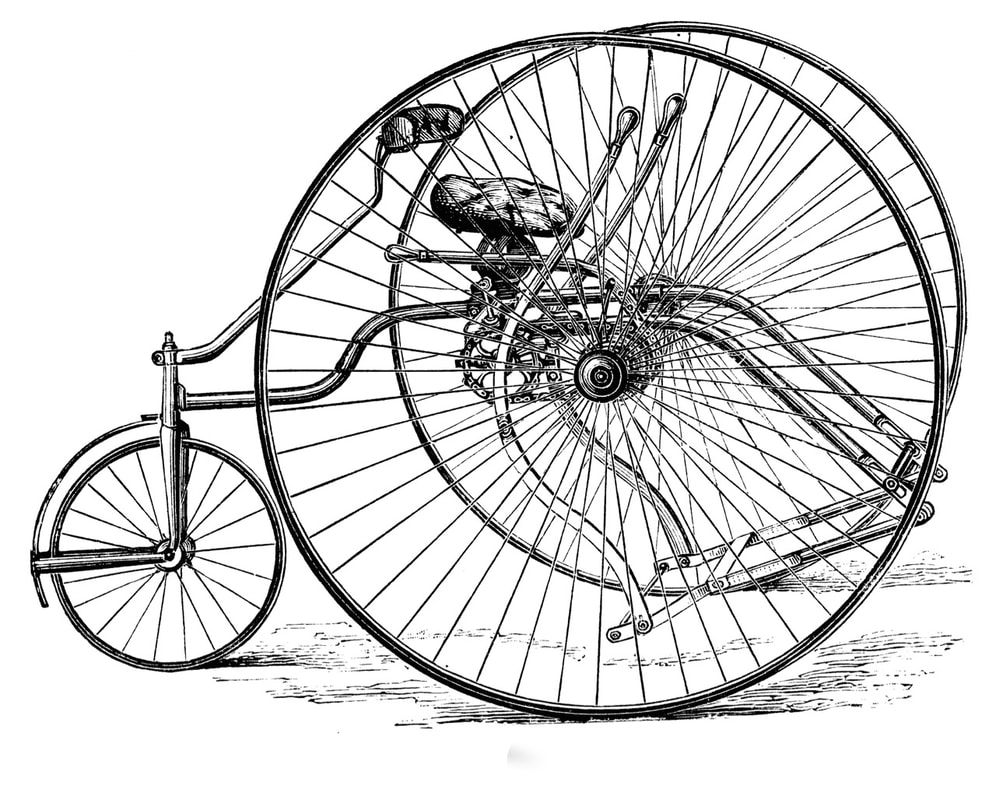

1881 model of Singer's Velociman, designed by Rev. Charsley Reproduced from Badminton Library Cycling of 1896 Pedal Power exhibition, Museum of Oxford (2009) Oxfordshire, cycling and their visual image in the camera. Cycle and photographic technologies were fruits of the Victorian period, and both were capable of causing excitement and derision in equal measure; one a poor man’s horse, the other a poor relation to the art of painting. Though initially restricted to certain social classes, they were destined to have profound social implications that are still with us; notions of self image and freedom. They both developed into major industries and helped spawn other technological and scientific advances, particularly in road transport and astronomy. This exhibition will focus on the 1880’s- 1890’s, when photography and cycling were in their relative infancy. Both technologies were developing rapidly, having yet to reach the era of mass production, and both were the result of many individual inventions and myriad small scale manufactures. This period culminates in the Rover “safety” bicycle and the box brownie camera, and is contrasted with the situation today, when again innovation is rife, but this time in response to environment and health concerns on one the one hand, and developments of digital technology on the other. Five individuals associated with Oxford will be used to illustrate the early impact of these intertwined technologies. Henry William Taunt 1842-1922 Taunt was the most prolific professional photographer based in Oxfordshire. He amassed over 60,000 glass plate negatives (although some were taken by assistants) and these comprise a unique social record of the Victorian and Edwardian period. Taunt produced one of the first photographically illustrated guide books on the River Thames. He was a familiar sight in Oxford traveling about on a tricycle; he had a two seater version with a photographic assistant in front doing all the pedalling. Flora Thompson 1876 - 1947 A novelist who wrote a highly acclaimed trilogy, Lark Rise, Over to Candleford and Candleford Green. In this she looked back at her childhood in the Oxfordshire countryside of Juniper Hill and the transition to an urban way of life. Thompson recounts the first sighting of a bicycle in her village in the early 1880's and again when they were mass produced and sold at a cheaper price which meant more people could afford them: “At first only comparatively well-to-do women rode bicycles; but soon almost every one under forty was awheel, for those who could not afford to buy a bicycle could hire one for six-pence an hour. The men's shocked criticism petered out before the fait accompli, and they contented themselves with such mild thrusts as: Mother's out upon her bike, enjoying of the fun, Sister and her beau have gone to take a little run. The housemaid and the cook are both a-riding on their wheels; And Daddy's in the kitchen a-cooking of the meals.” Text quotation from Lark Rise To Candleford, Author: Flora Thompson, PP. 493-494 Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press During the 1890s conservative elements of society regarded cycling as improper for women; some believed it might affect child bearing abilities or lead to moral ruin. Practically, there was the issue of how women could cycle in their cumbersome long skirts. This was not fully resolved until the manufacture of the drop frame ladies bicycle in 1887. By the start of the twentieth century, the bicycle had become a symbol in the struggle for women’s emancipation. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson 1832 - 1898 Better known by his pen name, Lewis Carroll, Dodgson was an exceptional portrait photographer of children. Like Taunt, he mastered the wet-plate collodion photographic technique which required plates to be coated with chemicals shortly before exposure. This was labour intensive and required great skill. Photographic exposures for this period could last from a few seconds to several minutes and presented a challenge to capturing movement, such as bicycles in motion. By the 1890’s, ready-coated plate negatives gave photographers more freedom. In 1882 Dodgson took a four mile ride on Rev, Charsley’s Velociman. Though much impressed, Dodgson felt that the steering, in which the rider leaned away from the direction in which he wished to turn, engendered a fear of being thrown off. He proposed several possible mechanisms to counter this design feature and one was developed to a prototype stage by Singer of Coventry. As it was not adopted, it can only be assumed that its efficacy did not warrant the extra complexity entailed. Rev. Robert Harvey Charsley 1826 - 1907 Charsley was a Chaplain of the Radcliff Infirmary in Oxford and in 1869 designed the Velociman tricycle. The inspiration for this came from his desire to develop a machine suitable for those in his care that had lost the ability to use their legs; industrial accidents were very common during this era. To this end, the machine was driven by hand operated levers that rotated the two front wheels. The full employment of the hands in providing power to the front wheels lead to an unusual method of steering the single rear wheel; a tiller bar was used, its position was controlled by the movement of the driver’s back. Although the velociman cost £28 which was more than the average annual salary, it was often purchased by a charity subscription list. Despite this, the Velociman was a successful design that had a wide appeal. As Charsley noted in a letter to the Oxford Journal of 1882, describing a 500 mile, 14 day bicycle tour he had undertaken: “During my tour I met several ladies and others on the velociman – one lady, 73 years of age, who was much pleased by the comfort of her machine.” It was manufactured for most of its life by Singer & Co. cycling company of Coventry, one of the world's leading manufacturers of bicycles. A derivative of the velociman was called the Manupede, and as the name implies this utilised not only the hands but also the feet, by dint of a treadle, in the generation of motive power. Charsley used a different name for this machine so as to dissociate it from any connection with disability; he himself having grown frustrated at being assumed disabled by the fact that he regularly rode a velociman. William Richard Morris, Viscount Nuffield 1877 - 1963 William Morris started his engineering and entrepreneurial career in Oxford, in 1893, as a young lad of 15 apprenticed to a local bicycle shop at 5 shillings a week. When Morris started his own cycle business, well into the era of the modern safety bicycle, he would have followed a typical model of the day: buying kits of parts from larger suppliers, assembling and finishing them, and perhaps adding extra features to distinguish his products from others. Morris himself often cycled the 120 mile round trip to Birmingham to collect the parts. He was a notable amateur cyclist winning over 100 championships. Morris was also representative of a large number of men who around the turn of the century were involved with bicycles and later became active in other industrial areas. Components that were new to the bicycle industry, such as gears, bearings and pneumatic tyres, were later to prove decisive in the manufacture of automobiles and aircraft. By 1910 Morris had wound down his cycle business and opened a factory in Cowley that would mass produce a range of Morris cars that would make him an extremely rich and influential figure. In summary This exhibition also looks into the future. The ubiquity of camera based technologies powered by computing, speed, surveillance, mobile phone cameras and internet sites such as Flickr and YouTube suggest that the photographic image has limitless uses and fascination. Conversely within the UK, cycling and cyclists have become marginalised, roads now being dominated by the car. Oxford presents a rare exception to this, but with the resurgence of innovation and current environmental concerns, cycling should have a bright future. However, it must be remembered that a cyclist “has only one heart” and that this physiological limitation presents many challenges to the organisation of society if bicycling is to match the ubiquity of camera use. Exhibition curated by Constantine Gras. Funded by Oxford City Council and University of Oxford. Notes by Andrew Hawkins and Constantine Gras, with assistance from David Hibberd. Footnote I began this project in May 2008 when I became interested in how Oxford organises its transport system, making contact with individuals who constitute this culture and thinking about how cycling fits into societal concerns about reducing our carbon footprint and the state of the nation’s health. As I began the process of research in early 2009, using the Oxfordshire Studies and the British Museum digitalisation of nineteenth century newspapers, I made many thrilling discoveries: the Taunt collection and Charsley’s Velociman were highlights. While the historical dimension engaged my attention, I also wanted to represent the contemporary vibrancy in my own photography; although many locals tell me there isn’t anything remarkable and that Oxford has a long way to go before it matches levels of cycling to be found in European cities like Amsterdam. I am truly grateful to all those individuals who have shared and shaped the vision of this exhibition. Constantine Gras, 2009 P.S. During the exhibition we were able to trace only one surviving model of the Velociman (a pioneer of modern handcycles), albeit one much modified over the years. A follow-up example was planned at the Nuffield Orthopeadic Centre to display and showcase the Velociman in more detail. Hopefully this exhibition might materialise one day. As of writing, 2 Dec 2018, I have been nursing a torn ligament in my ankle and cycling ironically offers the most pain free mode of transport. I fondly laugh about how a risk assessment was conducted in 2009 to facilitate the forward dismount from a penny farthing at Oxford town hall: YouTube. Constantine Gras, 2018 Henry Taunt photo from 1900 of the college tower at Magdalen College, Oxford. Reproduced from Oxfordshire County Council archives: www.pictureoxon.org.uk Rosa May Billinghurst, suffragette protest, 1910 Reproduced from LSE library Henry Woods with a Velociman, C1990s, Spalding Pedal Power exhibition, Museum of Oxford 2009

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed