|

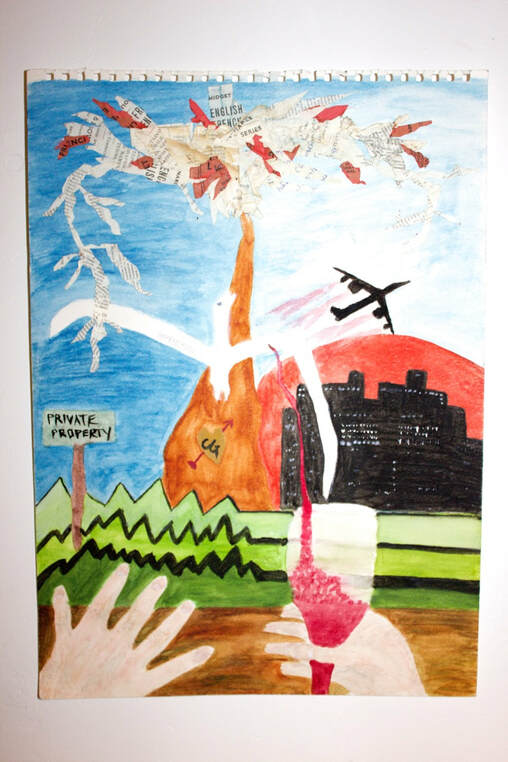

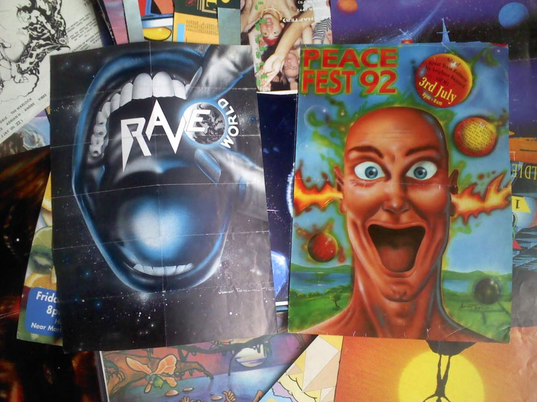

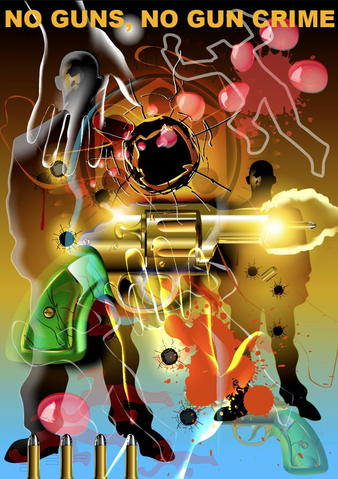

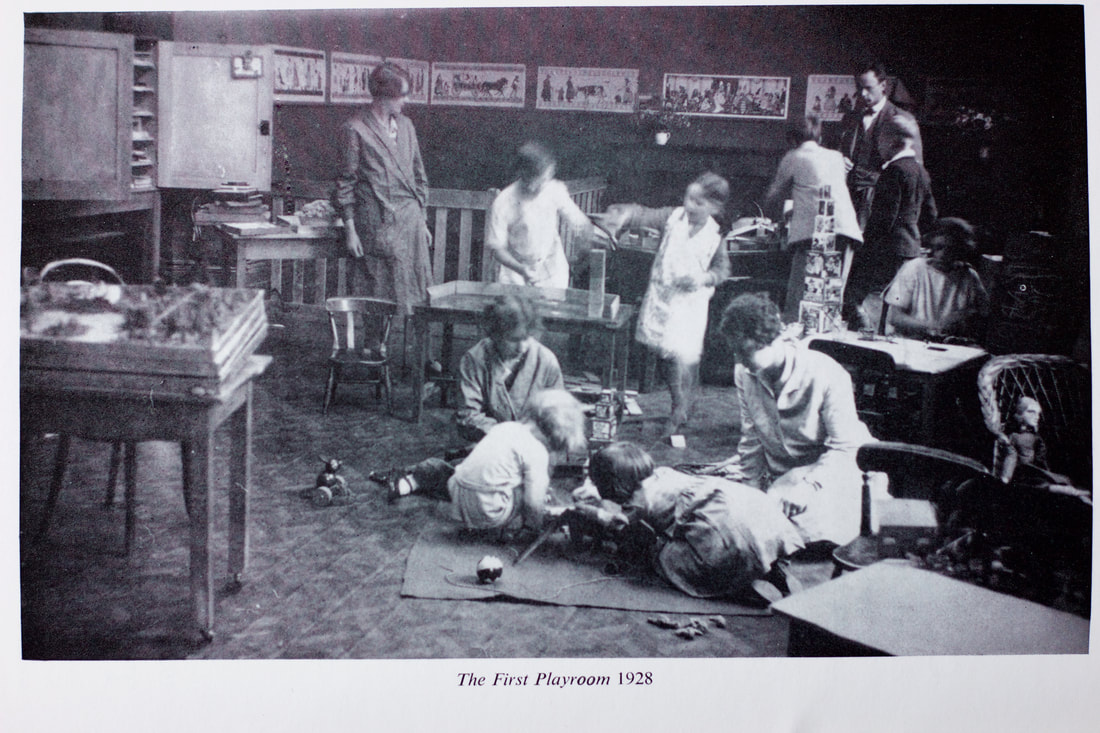

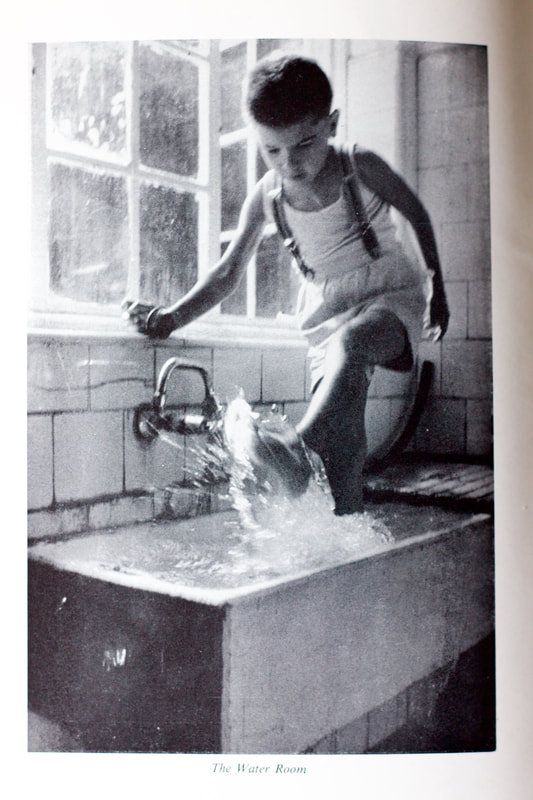

View of Bramley House (foreground), Silchester Estate high rises and Westway from the 17th floor of Grenfell Tower, 2015 If you put your ear to the ground, what can you hear? Perhaps Counters Creek - the subterranean stream that flows down from Kensal Green And threads past Silchester and Lancaster West Estates in North Kensington, London. If you start to excavate Lancaster West Estate, what fragments do you unearth? Possibly cups and saucers made by the Victorians and still serving post-war descendants. These are buried in the slum clearance of the 1960s and 70s. Now open up your inner being and listen to not just the stream and shattered shards, But the cries of people who were displaced by the town planners: During the first phase of redevelopment in this area Decades before the building of More West and the cladding of Grenfell Tower. The last words uttered, in-between sips of tea and beer. Here is one of those distant voices that rings loud and true: "To whom it may concern Having received your notice of your intention of developing this area And your formality to ask me to object, I SHALL, most sincerely, object on the below grounds: 1. Before I bought this property on Talbot Grove, I came to your Town Hall in person enquiring into any future development. A map was taken out, overlooked and I was informed that you had no immediate plan. I purchased the property. 2. After purchasing the property, I spent what is a large sum of money, to me (over £500) to insert a damp proof course, where after I was able to have a closing order removed. 3. I bought the property for private and undisturbed accommodation for my children. If their home had to be taken away, it would re-open a sore of housing accommodation and restrict their movements. 4. I have NO CONFIDENCE in the Kensington Town Hall. I have a genuine grievance which I believe is equally reciprocated by the Town Clerk and his colleagues. i have been in my opinion cheated and my feelings were expressed in various correspondence to him, Colonial Office and other officials, all to no effect. 5. As a negro, I have no status, I have NO ONE to whom I can go for sincere advice. NO ONE to whom I can seek redress. 6. If my property has to be taken by the Town Hall, I am sincerely afraid that it will be priced to suit the Town Clerk's wishes. I DO SINCERELY OBJECT Yours faithfully ........" North Kensington, late 1960s; consultation meeting regarding redevelopment Reproduced from Community Survival in the Renewal Process, PHD by Derek J. Latham, 1970 That was 1966. Here is another, less anguished, but equally desperate voice from 1971: "Dear Sir, Re: Town and Country Planning Act - 1962 Proposed Development at Lancaster Road, W11 Our main objection is that we fear not enough compensation will be paid, to enable us to purchase a similar property where we can live and carry on our business. A change of business will undoubtedly cause difficulties to our business. We feel that in running the Oriental Casting Agency, we are rendering an important service to the Entertainment industry by supplying them with mainly Afro-Asian artists. We are the oldest established Agency of this type in London, and we provide a livelihood for many Afro-Asian actors, actresses and models etc. A change in address would have considerable effect on the growth of the business, which has, in the past few years, been very marked. We have carried out numerous improvements to the property that was purchased in 1964. We would like to make it clear at this early stage in the proceedings that before we could agree to the development taking place, we would insist on the following points: a) Either we are provided with an alternative house of a similar type and condition, suited to our requirements. Or we are provided with adequate compensation. b) When and if we come to an agreement with the G.L.C. over this matter, we will be allowed at least ten months to enable us to make arrangements for the transfer of our business to the new address. Yours faithfully, .........." The Oriental Casting Agency. I suspect they might have supplied the plethora of Afro-Caribbean actors used in Leo The Last; the powerful film about an aristocratic slum landlord who is radicalised by his poverty-stricken community and whose townhouse is destroyed in the process. It had just been filmed on Testerton Street prior to that being demolished for the Lancaster West estate. Testerton Street, west side, 1969; where all houses are painted black by the set designers of Leo The Last RBKC Local Studies and Archives Walkway at Lancaster West estate built over Testerton Street Left: Salambo Mardi (acted by Christine Richer) Right: Leo The Last (acted by Edward Daffarn and Constantine Gras) Oil pastels, 16.5 x 23" 2015 We can trace a line of community protest through official and non-official channels. The ones that are officially recorded, pre-internet, are the petitions taken to the town hall. They tell a story of how residents organised themselves and attempted to shape the urban development of what was to become Lancaster West estate. Petition 1, June 1968 A petition was presented by Cllr. Douglas-Mann, urging the council to consider the plight of residents living within the boundaries of the development scheme who were unfurnished tenants. The recent housing survey undertaken by the Notting Hill Summer Project had shown that there were 167 furnished tenancies and all the families living in these cramped rooms, often without heating or water, were in need of being rehoused. Social workers and community organisers were raising this as a major concern. This petition was signed by 1,194 residents with 538 within the development area. The council at the time was under no obligation to rehouse furnished tenants but would consider cases of genuine hardship. The priority was given to those on the waiting list. Petition 2, June 1969 The following statement and petition was handed in to the Deputy Town Clerk by Mr J. Denham of the Lancaster Neighbourhood Centre. He and 30 children and 2 mothers had marched from North Kensington to the town hall. "To the Council, Sirs, We are told that the infant mortality rate of our borough is 40% higher than the average for the other London boroughs. We feel that child care in this borough is as good as in any other. Our conclusion is that the bad and often insanitary housing prevalent in North Kensington, overcrowded conditions, and lack of playspace and amenities constitute a direct threat to the health and happiness of all children in North Kensington. In view of this we urge: 1) That there should be more provision made for the rehousing of large families under the Lancaster West Redevelopment Scheme 2) That no family shall be evicted under any clearance scheme, whether they are furnished or unfurnished tenants 3) That North Kensington should be considered a housing emergency area and that all available local and national resources should be mobilised to see that every family in North Kensington has a decent house. Lancaster Neighbourhood Centre." The council generally regarded furnished tenants as mobile and of temporary duration, but would consider for rehousing those were who were long-term residents and who had genuine hardship. Petition 3, Nov 1974 Cllr John F. S. Keys presents a petition protesting at the conditions of the roads and footpaths around the Lancaster West Redevelopment Area. This was signed by 250 local residents. "We call upon the council to take immediate action to eliminate the danger to pedestrians, cyclists and motorists." The Council noted the concern and although this was beyond the normal resources of its cleaning service, would consider the possibility of introducing an Environmental Code of duties for contractors. Petition 4, July 1978 A petition signed by 135 residents and children of Lancaster West Estate calling for more open play spaces in the area. The council believed the residents were not aware of their plans to include more play spaces in the development. Petition 5, May 1979 Cllr. Ben Bousquet presented a petition from tenants of the Lancaster West estate urging the council to reconsider their policies of switching off the central heating at estates at the end of april and extending services until the end of may. Petition 6, November 1981 A petition was presented signed by 238 residents which contained the following "prayer": "We the undersigned residents of the Lancaster West estate demand that the council gives priority to resolving the problems caused by the plague of cockroaches, bugs and other insects in our homes. Further, we understand that these insects constitute a health hazard and we are taking legal advice to our rights against our landlord, the council. Meanwhile, should nothing be done we may consider withholding our rent and rates until those insects are eradicated from our estate." The council noted that cockroaches had gained a foothold in ducts and pipes at Grenfell Tower and Camelford Walk and were responding to this. Although a pest, they have little medical importance beyond the psychological effect of their unpleasant appearance. It was difficult for the council to access flats as a blanket treatment would be carried out to prevent further spread; legal forced entry might be required. The other insects mentioned are thought to be ants which appear from time to time on the estate. Tenants would be left to deal with this themselves. Edward Daffarn reading from a petition handed to the RBKC Scrutiny Committee, 2015 Petition 7, January 2016 Grenfell Tower Residents address RBKC Scrutiny Committee The residents had invited me to attend and document this meeting. This is a summary of the speech given by Edward Daffarn: "Thank you for allowing the residents of Grenfell Tower the opportunity to inform the Scrutiny Committee of the ill treatment, incompetence and plain abuse that we have experienced at the hands of the TMO during the Grenfell Tower Improvement Works. I am speaking to you in my capacity as a Lead Representative of the Grenfell Tower Resident Association, that was formed through adversity, in the summer of 2015 with the support and encouragement of our local MP, Lady Victoria Borwick. To back up the testimony of Grenfell Tower residents to the Scrutiny Committee members of our R.A recently conducted a quantitative survey of leaseholders and tenants to measure levels of resident satisfaction / dissatisfaction as a result of the TMO's handling of the Improvement Works. The findings of this survey are truly shocking. The survey revealed the following facts: 90% of Grenfell Tower residents have reported that they are dissatisfied with the way in which the TMO has conducted the Improvement Works. The survey found that 68% of residents said that they had been lied to, threatened, pressurised or harassed by the TMO. The survey also revealed that 58% of residents who have had the Heating Interface Unit (HIU) fitted in their hallways would like them to be moved to a more practical and safe location. As a result of the findings of our survey and with the support of Lady Borwick, the Grenfell Tower Resident Association is calling for the Scrutiny Committee to commission an independent investigation into the Grenfell Tower Improvement Works, not least, so as to prevent the traumatic experiences of local residents being replicated when the RBKC undertakes the Improvement Works to other tower blocks in North Kensington." Link to full speech on the Grenfell Action Group blog. At the Scrutiny meeting, the council agreed for an investigation to be undertaken on behalf of the residents. However, this was to be managed by the TMO. I was artist in residence at Lancaster West estate from April 2015 - June 2016 where I interviewed all of the original architects about their vision for the estate. I was not allowed direct access to Rydon and the other contractors tasked with the renovation of Grenfell Tower. Although commissioned by the TMO to make a short positive film about the works and to produce an art work for the new community space, I found myself deviating somewhat from the brief, especially once I started to listen to and record the life stories of residents. For a previous project, I made art with residents from Silchester Estate that drew on the social and mythic parallels with Leo The Last. This time around, I felt more like Leo, the individual who is observing and then directly implicated in the ensuing struggle that was taking place between residents and TMO/contractors/council. The film I made was a one hour portrait of residents. This was visually admired by the TMO, but was rejected as not fit for PR purpose. The art work made by children during the Grenfell fun day also languished and was never displayed in the tower after the works were completed. Silchester Baths photograph, protected during building works in the lift lobby at Grenfell Tower, 2015 It should be noted that throughout its forty-year plus history, Grenfell Tower only had one art work on display. This was an evocative archive photo of Silchester Baths, the Victorian building that was sited near the tower and which critically altered the original masterplan as it became temporarily listed before being demolished; it subsequently became car parking, green space and is now the site of the Aldridge Academy. There was never a description included with the photo to explain to newer residents why the Baths were of importance to the local area. I raised this with the TMO, but it was not important in the scheme of things. With my ear and inner being, I hear and then evoke..... Generations of residents living in houses at Testeron Road as they bathe their bodies and wash their clothes at Silchester Baths. The Baths and houses were caught in the red line of Slum Clearance programmes. A film maker took hold of Testeron Road prior to it being wiped off the map by the council. A false posh house was build by the film crew and then cinematically destroyed. Leo The Last tells us that we can't change the world, but we can change our street. Out of a ruined landscape, Testerton Walkway was built, one of the three blocks of housing that radiates out from the tower. Grenfell Tower was renovated from 2015-2016 with an artist employed on site. 72 people died in the fire on the 14 June 2017. When I think of Silchester Baths, Testerton Street, Testerton Walkway and Grenfell Tower, they should all be an interconnected and positive inspiration for how we manage space and housing; how this relates to play, heating, the control of pests and the consumption of social cups of tea. We symbiotically draw our health and wellbeing from the underground currents. Alas, those currents contain an equal measure of bitter tears and spilt blood. Tuesday, 25 July 2017 Grenfell Tower Inquiry Consultation on terms of reference A voice from the floor: "Looking at Grenfell Tower is like peeling back layers of the onion. At the surface a range of issues about building safety and failure of services to respond adequately to an emergency and tragedy. Behind that is the history of contempt and neglect that enabled those building regulations failures. But behind that is the reality of discrimination. The process that decides who it is gets burnt to death and who sleeps happily in their comfortable homes. Many survivors have put their fingers on that underlying reality. They were given unsafe housing and the terms to make it safe refused or ignored because of who they are. They are by and large on modest incomes, black and from ethnic minorities or migrants. This is not just about housing allocation in Kensington and Chelsea. Some of those killed were private leaseholders or private tenants. It's about how some people end up in worse housing, and then it's about how those people are treated as residents, as citizens, that they are effectively excluded from the important decision and that compounds their disadvantage. That's not just a problem in Kensington and Chelsea, but sadly there's nothing worse than Kensington and Chelsea." Artist studio at Shalfleet Drive, 2015

A map of the listed buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea I added Silchester and Lancaster West Estate to the list as they were threatened with regeneration

0 Comments

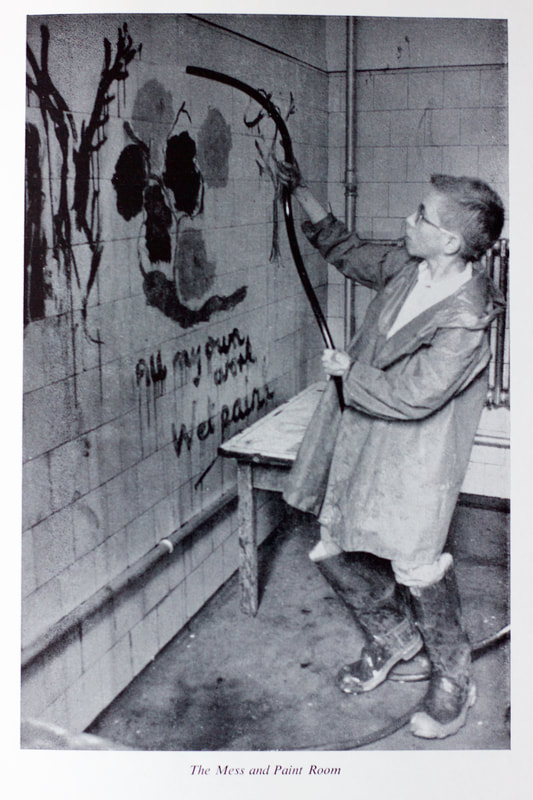

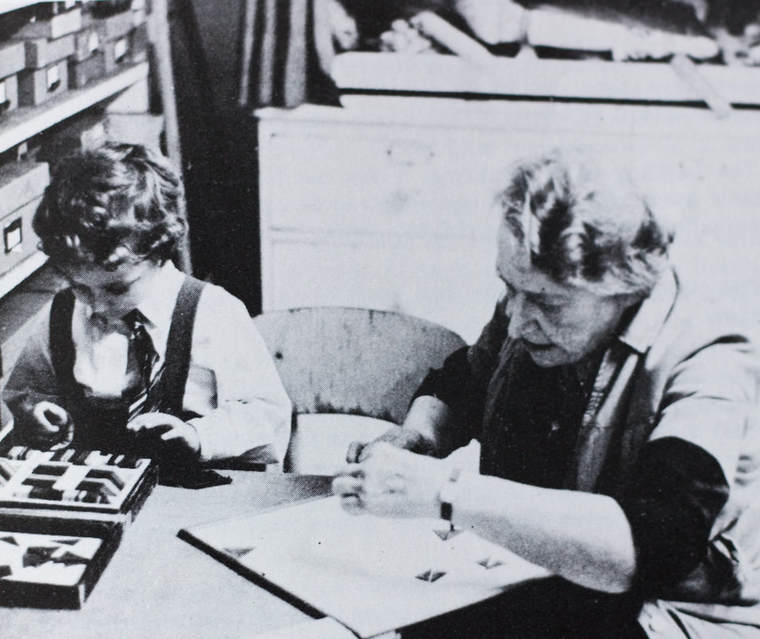

You are on a mission, but beware - there is no past and there is no future.

Baudelaire did not fly or Rimbaud die and Lemy Caution is missing in action.

Rendezvous: "Brown tie?"

Password: "And braces!" I am waiting here for the French agent with feathered hat.

The phone does not ring.

Still waiting. I am distracted by the kamikaze dive of a demented fly. In one hand, a book of poetry by Anna de Noailles. The other to mouth, sipping champagne out of a cracked glass. I spy a refracted card being delivered under the door. This facet a clue? That one a trap?

At the Institute I am ushered into a meeting room.

The silhouetted outline of a man is framed by a monstrous clock. It has no second or minute hands. The machine activates and my brain quivers.

I come round on the floor in a darkened cell with a folder in my hand.

I crave to read the contents, but.... I... wake.

I... wake on a bench outside the Louvre which is turning inside out.

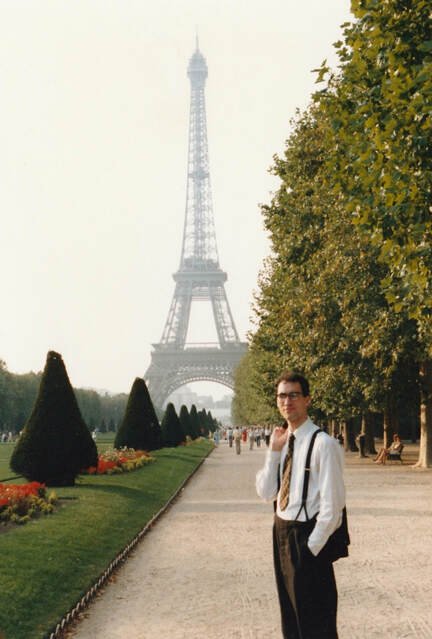

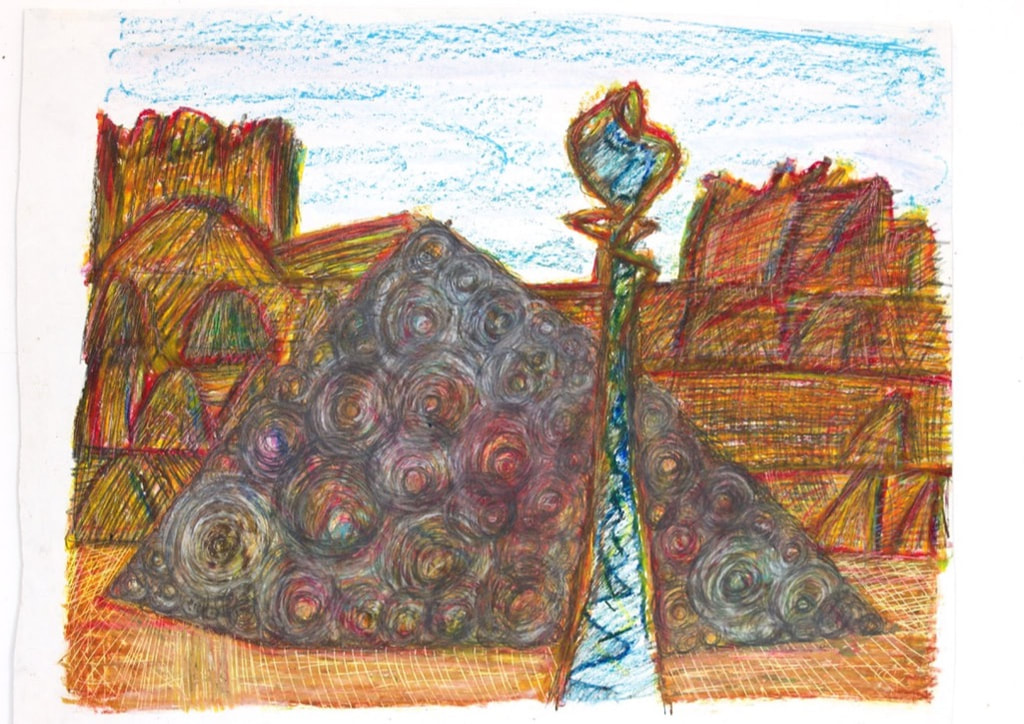

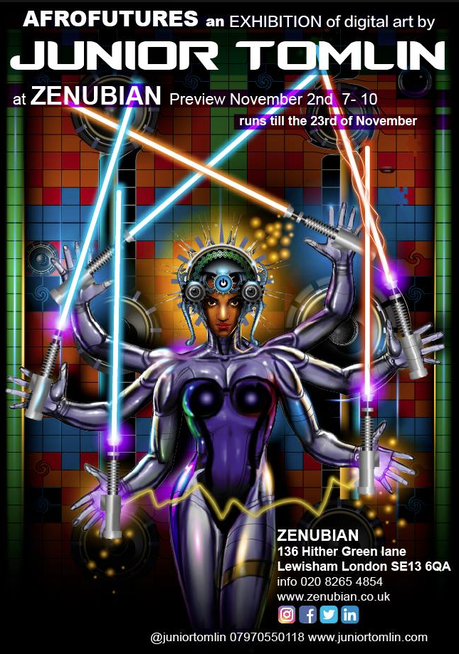

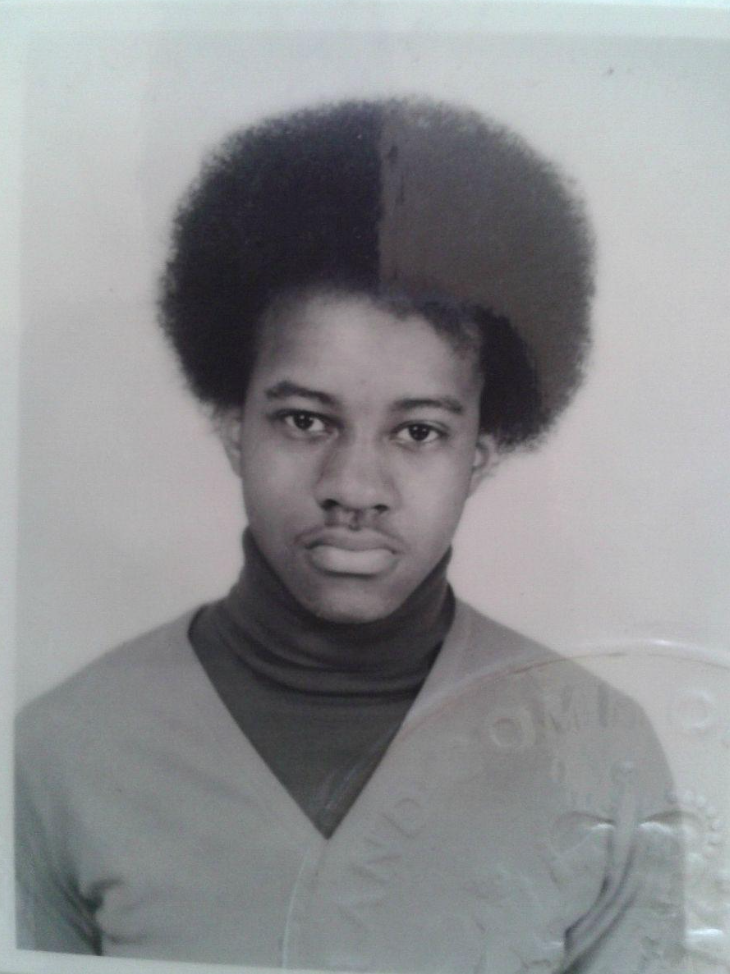

My memory has been semi-erased. Was I.... a.... European son? Madeleine? Painting 1: The Poet's Elixir After Baudelaire Or in other delirious words: "Pretty witty twoon. Swoony noon loon." Acrylics and collage. 10 x 14" 1991 Photo: Down and out in Paris Summer, 1987 Business card Hotel de Champagne et de Mulhouse, 1987 Leaflet Advance Computer Institute, Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre, 1987 Folder 1986: Visnews International news agency that broadcast the first daily satellite news service. Drawing 1: Louvre, Outside In Oil pastel and pencil, 22 x 17" 1996 Drawing 2: Louvre, Inside Out Oil pastel and pencil, 21.5 x 19" 1996 Filmic sub-text: Cléo de 5 à 7 Directed by Agnes Varda, 1962 and starring Corinne Marchand Alphaville: une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution Directed by Jean Luc-Godard, 1965 and starring Eddie Constantine A blog entry inspired by seeing these films after an absence of 30 years; akin to waking from a dream. I will overcome e-motion and travel sickness in search of past-tense, future-flex. It's a pleasure to feature digital artist and comic colourist, Junior Tomlin. I've been tracking Junior's fab work and interviewed him ahead of his latest exhibition, AFROFUTURES. This has its preview on 2nd November and runs till the 23rd of the month at Zenubian, 136 Hither Green Lane, Lewisham, SE13 6QA. I wonder if you could describe a bit about your childhood and early formative experiences? I was born in 1960 and grew up in Ladbroke Grove. I have two sisters and a brother. My parents were Jamaican. They came to England in 1958. My father worked for British Rail in Euston and he was a shunter. Mum was a cleaner but was also creative in her own way. I remember going to work with her in the 70’s to help her clean the offices in Baker Street. I went to my local junior school on Oxford Gardens and then to Christopher Wren in White City. After secondary, I went on to do a foundation course at Byam Shaw School of Art in Notting hill. After a year, I did three years at Goldsmiths studying graphic design. I was a keen collector of comics as a child in the 1970s (sadly having lost that collection). I had no dreams then about being an artist. I wonder when the bug got you? The drawing bug started when I was young, 8 or nine. I was one of the children that didn’t have a lot of paper or pencils; but I did had a favourite pencil that was purple. I watched Lost in Space and that sparked my interest in robots. I love comics. The first one I bought was the mighty Thor and I still have this. I think looking back, that I am a lover of mythology. At school we used to draw the Marvel characters and being the best artist in the class, the other kids asked me to draw for them. Years later, one of my old school friends thanked me for helping him in his artwork. I still have all my comics. I have heard the universal story of mum throwing out their sons budding comic collection when they were out on a school trip. Where did you work and who, what and where was the London Cartoon Workshop, that I've heard about? The London Cartoon Workshop started in the offices of One Step which was in a building in Old Oak near the station. It was set up to teach sequential art i.e. comics. We had tutors from the comic book industry. I worked as an airbrush tutor and we made a comic entitled Silicon Fish. Maximum mention to David Lloyd and Amalia who were the core heart of the workshop. It moved years later to Kensal Road. I later went on to work for various companies such as John Brown Jr. Publishing, Titan and Panini - famous for producing football stickers and licensed to produce Marvel comics in the UK. I worked as a digital colourist for them with credits including Action Man, Transformers Armada, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Judge Dredd and numerous pocket book covers. The rave scene and the film industry were an important part of your development. Please tell us more about this period in your life and art. The rave period in my art development started when I was at the offices of Kickin Records. At the time, I was designing record covers for dance music. There I met a rave promoter looking to put on his first rave called Raveworld. From this, I did some of the best remembered and iconic images associated with dance and rave music. I created images that have inspired many to create art and to explore their artistic talents and become DJ's. I was given the tag "the Salvador Dali of Rave". My first endeavour in film was when I got a job on Nightbreed, a Clive Barker horror Film. I was a creature technician and my task was designing and creating masks to be used in the film. Years later, I worked for AMG effects where I was employed as a texture map artist. The job was designing and putting textures onto 3D objects. How has your style changed from analogue to digital techniques and what can we expect to see in your latest exhibition? Moving from analog to digital wasn’t hard for me. The three things I had was a computer, the right programmes and a digital tablet to draw on. My style hasn’t changed much. The ideas start with pencil and paper and when the design is good enough, I would scan it and start the magic. I use a mix of Sci-Fi fantasy and some images have a social political narrative. The current theme of my exhibition is Afrofuturism. Images to make you think and a feast for your soul. My work is as colourful as African fabric. As a footnote, do you mind if I ask you what it means to live in North Kensington and the impact of the fire at Grenfell Tower. The loss of 72 lives, has really affected us. I saw that you posted a powerful cruciform image in response to this. North Kensington means home to me. It’s where I’m strongest artistically and spiritually and where my ideas for art come from talking to friends. The neighbour hood is forever changing. I thought that the community was on the wane, but as a result of Grenfell it has been made stronger. With Grenfell I ask myself: why? There is no one answer. It’s multi layered. Grenfell was a draining episode and I felt I had to help. I volunteered. I wanted to make a difference. I just put this graphic image together. This was a hard time for me and my family. A month before Grenfell my mum passed and being a volunteer helped me take my mind from clearing mums flat. And just to end on a more upbeat note. I like to dress rather formally and I take my hat off to Junior, who is a smart dude and what was that WW2 aviation hat, I once saw you wearing? Hahahahaha! The hat. I love hats and so did my dad. The WW2 one? I went into the antique retro shop on Portobello: saw it, loved it and bought it. Hats should make us laugh! Anything else that tickles your funny bone? And any advice to budding artists? What makes me laugh is slap stick, good stand up comedy and the genius of Monty Python and Dave Allen. Remember to believe in your art. Don’t let it get you down. Create, produce and get your art out there. You are awesome and the next piece of art you do will be better than the last one. Photos and art work kindly reproduced by Junior Tomlin. Margaret Lowenfeld (1890-1973) was a pioneer of child psychology and play therapy. She was able to make creative connections of the highest originality. The child-centred philosophy she developed and its process of therapeutic play-making was the culmination of many factors: central to these being her experience of children traumatised by World War One; and also her observation of the colourful patterns in Polish folk costumes. Her work and legacy has influenced my thinking and art practice, both before and after the Grenfell Tower fire that occurred on 14th June 2017. I have always used a model of art making that was rooted in play and non-verbal processes of communication. I was able to use this during Art for Silchester, a seven month residency that has just ended at Silchester Estate. I worked with residents and children who live across the road from the tower and each of whom are coping with the tragedy in different ways. During these sessions, we made large scale drawings and ceramics which were indirectly connected with the therapy of Margaret Lowenfeld, who first started her work in this area of North Kensington in the late 1920s. I also recently met up with Margaret Lowenfeld's great nephew, Oliver Wright, who is one of the therapists working with the NHS in providing support to local residents traumatised by the fire. But this blog is an interview with Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock that was recorded from July-Sept 2018. She is retired from practice, but was trained at The Institute of Child Psychology in the early 1970s and was the leading proponent of Lowenfeld Mosaics as applied to child psychotherapy. In talking about her life and work as a Lowenfeld therapist, I was also able to open up and have a reflective space to think about my own feelings, my inability to voice them over the past year and how I am now moving forward as a person and artist. A war child in Hong Kong and China I was born in Hong Kong, a British colony in 1935. My parents were both teachers. When they graduated from university they started their own school based on my mother’s ideas. She was an intuitive teacher and had this notion that when you teach a child it isn’t just the teaching that counts. It is also about the child. In Hong Kong during the 1920s and 30s that was a rather unusual idea. When the Japanese took over Hong Kong they changed all aspects of our lives including our consciousness. When my brother was born, my parents decided they didn’t want to live under the Japanese and they went to Canton, China. We had nothing and squatted in an empty house. My parents had to have two jobs in order to have enough money to feed us. I was left on my own and wandered around quite a bit. I once stumbled across this march. Being small and very inquisitive I wiggled to the front. There were two Chinese men being executed by the Japanese. The whole crowd watching was Chinese. As soon as one of the prisoners stepped forward the crowd cheered. Then a band of soldiers tried to shoot him but he kept on spinning and it took a long time for him to fall. The crowd just kept on cheering. I was an innocent child and didn’t know anything about politics, but I thought: fate was going to show the people this was a good man. Children see things that they don’t understand and they have to make some sense of it. I didn’t see him fall and I thought he was a good man. That thought came to me as a child and I only found a word for it, patriot, when I came to England. So the words come much later in my understanding. After some time my father returned to Hong Kong to see when it would be safe for the family to return; leaving my mother, my baby brother and myself in Canton. It was during that period that I met a Japanese boy. The meeting was very curious because the Japanese boy was trained to think that Chinese natives were bad. I was walking with my brother in my arms and he threw a stone at me. It hit my elbow and I got really angry. I rushed home, dumped my brother on the bed and went back. I said you hit me and I’m going to hit you back. It was very foolish of me because I was eight and very tiny. He was about ten or eleven. He was so shocked because I could speak Japanese. He then said: if you can speak Japanese, you must be educated and civilised. So he wouldn’t fight me. We became friends and I learnt even more Japanese from him because I didn’t have anyone else to play with. My mother knew nothing about this Japanese boy because she was so busy earning our rice. Just meeting him prevented me from thinking that all Japanese were bad. This later fed into my understanding that all group prejudices were a generalisation of personal experiences. Life is not simple. It’s not reasonable. It is not governed by things like - if this happened here, then that happens there. There is a war, but for the individual child all kinds of experiences are possible. These were war-time relationships and had no consequence afterwards. But even now, I sometimes wonder what happened to that Japanese boy. A scrambled education and life in post-war England We came back to Hong Kong in about 1946 with a wheeled cart and the little luggage we had. My father had found a flat. I continued to look after my brother but not for long. My mother wanted me to go to school, but I had missed three years and so my Chinese wasn’t up to standard. So she decided to put me into a school where the teaching was in English. I didn't know any English. I was 11 and had to spend the first few months writing nothing but lines: I MUST HAND IN MY HOMEWORK. I was always semi-bottom of the class. In my school leaving year, I failed in everything because I couldn’t be bothered to study. It just seemed too difficult. My mother asked me if I would be happy to be a street sweeper or a secretary. It was then that I realised the value of an education that enabled the individual to have a wider choice in adult life. So that year I started to study. When the exam results came out they would be published in newspapers and the top 50 students would get scholarships. I got one. That was such a shock. I later discovered that my mother had been saving money for my education. But my father would always say - don’t overeducate your daughter because she won’t get a husband. You can see there were two very different philosophies in the household. But in the end he was very proud of me. At university I knew I had to study hard. I studied political philosophy. I did psychology, I did logic. All the kinds of things you don’t get at school. Wonderful. I was just enjoying my life. I wanted to become a librarian because I love books. The only post-graduate course on librarianship in the whole of the UK was at University College, London. They had lots of foreign students but they only accepted people with First or Upper Second Class honours degrees. I was very lucky to get in. They said do you have a classical language? I was very cheeky and said I have Chinese. I didn’t tell them that I only studied basic Chinese. They said, they didn’t have a Chinese student and we’ll take you even if you haven’t got any Latin or Greek, nor German or French. This must have been in 1958 and it was a one year intensive course. During the second term I had pneumonia. I was staying in a university hostel and the registrar who was looking after me thankfully had a nursing background. When I went to take the exam, there was no way I could pass it. I passed one paper. I failed the other. They said we really want you to pass, so come back. But I had no money and the course was teaching you how to catalogue Latin manuscripts for working in a university library. It was not for public libraries. I thought this is all too alien and that I couldn’t continue. Domestic life and the discovery of a vocation I then thought I might enjoy teaching but got married and had children. I had to learn how to be a housewife and mother in England. All without any help. What I discovered was that I could talk to another PHD person but I didn’t have any ordinary language. My husband was working in the Midlands as a salesman and he travelled all over the place. We were living in a new estate which had just been built and I didn’t know anybody there. The biggest town was Bromsgrove and that was at least three miles away. We had no telephone. My husband just thought: this is your domestic scene and he decided to have a mistress. I said, this isn’t right, is it? We can’t carry on together when there’s no connection. So I was in a terrible bind and came back down to London. Then he followed with the children. I had to get a job. As I was the one who left, I had to help with the family finances and earn enough so that my husband could have some of my earnings as well. Then I met Jasper. We discovered that maybe we should get together. Jasper and I were married for 46 years and the children lived with us. The children have always thought of him as their dad. During this period I also had personal therapy. The therapist said to me: I can see that you don’t want to be a librarian anymore or a teacher. Do you have any ideas? I said: yes, I want to sit in that chair (pointing at her). I’m going to be a therapist who sees children. First Mosaic made by Therese upon arrival at the ICP, 1969 The Institute of Child Psychology (ICP) I went to Hampstead to visit the Tavistock Clinic. They said you can’t see anybody because they are seeing children and they are in private practice. I said: how do I find out about your training? Well, you’ve got to come to attend our courses. How long will this take? The lady said: it depends on the individual but it could be 4 or 5 years and the student would need to have personal psychoanalysis as part of the training. I just didn’t have the time or money for this. So then I went to visit the Institute of Child Psychology in Notting Hill and they said: Dr Lowenfeld will see you, but she’s with someone else at the moment. They gave me a Mosaic to play with while I was waiting. It was a very clever idea. I knew nothing about what I was doing. It was fun. I made this tree and plane in my Mosaic. In hindsight, I realised this encapsulated my journey and life here in England. The tree was me growing up and the potential to develop in this country through the course. What I didn’t know was that they kept records of all Mosaics and when the Institute closed, I looked through the records and rescued my Mosaic. Margaret Lowenfeld was one of the first child psychiatrists who was interested in finding ways for children to express themselves without only using words. She thought about what happens to a child between age zero and seven. How do children of that age think? She realised that what children perceive is multi-dimensional and cannot be put into words that are in linear time. The child has many ways of seeing the world and they formulate ideas through their sensorial experience. Lowenfeld had this notion that they do it through pictures. So she had this idea of picture thinking in the late 1920s and 30’s and pioneered the use of Mosaics and the World Technique; the latter known more generally as the sand tray used with miniature toys in dry or wet sand. These are play and language tools for the children to express themselves without relying solely on words. Lowenfeld opened the Children's Clinic for the Treatment and Study of Nervous and Difficult Children in North Kensington in 1928. This offered a unique form of therapy for children that did not exist anywhere else in the country. Before the Second World War, the clinic was very well known and mainly supported by private funds. Lowenfeld wasn't charging the local people very much because this was a poor area and she wanted these children to have the use of these facilities. Photographs of Margaret Lowenfeld and children using the World and Mosaic. There was a change of name and The Institute of Child Psychology relocated to 6 Pembridge Villas in Notting Hill Gate. The Institute had facilities that were exclusively given over to the self-generated play activities of children. There was a big basement to the house where the playrooms were located. The children could play ball and use climbing frames. There was a trunk on wheels which the children could hide in. Another trunk had clothes and hats and objects. This was used for dressing up and often lead to dramatic play in innovative ways. There was also a painting room where the children could paint on the walls. You could hose off the paint with water to obliterate the child’s painting should the child not wish for the painting to be kept. There was also a water room where you could have water and toys on the floor and we all had to wear waterproof clothing and wellingtons. The older teenagers might think that playing was too childish and so they could talk in what we called the Quiet Room. Occasionally we would take a Mosaic in for them to use. The Institute always had a file for each child’s therapy work that included a recorded copy of all their Worlds, Mosaics, drawings and paintings. At any given time you might have 6 therapists with their children in the playrooms. We worked together as a team, often helping out by observing other children when the therapist might have missed out on some aspect of their child’s action. It was also a very demanding training. I could write about 12 pages of notes that documented what my child did in any given session. We would never impose a point of view or interpretation of their play. The aim of all this was to allow the child to express their point of view and feelings through play. I started my post graduate course in 1969 and this lasted three years. We only had two new students per year. We had daily supervision, but on Tuesdays and Fridays we had two hours of group supervision to discuss what we called Corporate Cases; these were the children who were not solely the patient of a particular therapist. In the student’s last year, they would be supervised by Lowenfeld. I liked doing the Mosaic and the World with the children. It could take two sessions to do this because sometimes children take forty minutes to do a Mosaic. I prefer to use the Mosaic because they have a progression or a regression and they tend to be linear. I don’t interpret the mosaics. I talk to the children through it and then sometimes they will tell me what it means. The Lowenfeld therapist always had to be lower than the child. I would sit in a chair that is the same size as the child. I’m lucky because I am fairly small anyway. Lowenfeld was not psychoanalytical. She said her ideas were only just one philosophy and so we were taught about Freud, Klein and Jung. She said you will need to understand what other professionals might tell you about the child under consideration. The Institute had a child psychiatrist, an educational psychologist, a social worker and a West Indian social worker, as the area the ICP was in had a lot of West Indians. I think I had an excellent training and it never troubled me that the psychoanalysts thought I was not trained. Lowenfeld had set up a proper postgraduate institution and awarded postgraduate diplomas. They had an academic board who oversaw standards. That’s why I got a student grant because it was properly recognised by the national Education Department. Case studies and sexual abuse I remember this nine or ten year old girl who came to the Institute and just stood rigidly. She believed that her back was made up of one bone and that she couldn’t bend her body. She only spoke in whispers, not wanting to expend her energy reserves. She was worried that she would die and had stopped eating. I said to her: do you know what our back is made up of? She said there’s a bone there. I said your quite right but there’s not just one bone but many bones. I’ll show you. We had these models. I got her the skeleton and I went slowly down the spine guiding her hand so she could feel the knobs. The first treatment objective was to get her to learn about moving freely. We often did body work because, for instance, many girls didn’t understand about menstruation. There was also a fifteen year old Indian girl who was very unhappy and wasn’t eating. She told me she was going to have an arranged marriage but wanted to go to university. The parents felt that any further education would be unnecessary since their aim was for their daughter to get married immediately after leaving school. To enable her to get into university, I said: you have to go to the library rather than home to do your school work. Sometimes therapy is being pragmatic for people to get out of these difficult situations. You’ve got to offer them a solution that will relieve them from that. Only then can it be analysed and if the child wants it to be. What happens if the daughter is expected to sleep with the parents? I said okay. Which side of the bed are you sleeping? I’m sleeping on the right hand side. Who else is in the bed? Mummy is on the other side. So I asked who is in the middle. That’s daddy. I asked her how she liked the arrangement. This is a thirteen year old girl and was a case of sexual abuse. There are girls who I can discover their issues through their World Play or like that girl who did a Mosaic. She kept on shoving Mosaic pieces in between other pieces. I said sometimes that happens to older people as well. She nodded. I said: it also happens to girls. What you need to do, to stop this, is to tell an adult. There’s a law that allows me to talk to you about this. I was getting somewhere with one child who was telling me the parents were abusing her. The parents then stopped her coming to see me, saying Mrs Woodcock’s English is so poor that my child can’t understand her. You can’t argue with that. What I said to the girl was: I’m sorry this is your last session because your parents are not happy about you coming. I said: you know what the problem is. You are fifteen and by the time you are sixteen, you can leave home. That was all I could say. Perhaps there are limits to the therapeutic process. Lowenfeld never talked about sexual abuse at all. You would think she never knew about it. But you see nobody was talking about it at the time. The biggest change I saw over these years was actually having abuse recognised and also the legal aspect of myself and social workers having to report it. I thought that helped me to talk to the children. By law, I had to report this and some other professionals were then able to help the child. In Summary I am extremely grateful to have attended the course at the Institute of Child Psychology. It enabled me to help children by using the World Technique and the Lowenfeld Mosaics. When I graduated in 1972, I worked for the NHS and child guidance clinics in Newham, Haringey and Barnet. Both Haringey and Newham were multicultural and deprived areas. I didn’t actually want to work anywhere else. That was a personal choice. I wanted to work with a variety of children including the poorest. I saw my last case in January 1995 having worked as a Lowenfeld therapist for over 20 years. A selection of my work will be housed at the Wellcome Library as part of the Margaret Lowenfeld archive. Expressing the shape and colour of personality: Using Lowenfeld Mosaics in Psychotherapy and Cross-Cultural Research By Therese Mei-Yau Woodcock, Sussex Academic Press, 2006. Photographs and text kindly reproduced: © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library. Postscript Let us end with Margaret Lowenfeld's account of the first day the Clinic opened on Telford Street in 1928. This was in rooms hired from the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre (aka birth control clinic) where Margaret's sister, Helena Wright, worked as the Chief Medical Officer: The two rooms that allowed for the Clinic's work consisted of one opening direct on to the street, which we used as treatment room for the children, and a second room opening out of it. Here records could be made and kept, parents interviewed, biomedical investigations carried out and discussions conveniently held between myself and my colleague. Money was short so the playroom furniture began as one table and three chairs, one of them a fireside chair placed between the diminutive gas fire grate. The play material was kept in the second room and carefully selected for each child who came - it was too precious to be indiscriminately displayed. Later a second table was added for the children to paint on, the first round table remaining in the centre of the room. A scene in which this table figured later won us our crucial friend. The first child who came was the "bad boy" of the neighbourhood, abominated by the shopkeepers. He came by himself and I do not remember seeing his mother. He was defiant and silent but remembering the Polish children, I left a French painting book - these were lovely (good ones being practically unobtainable in England) on the table with water and painting brushes. He seated himself with his back to the centre of the room and studied them. Half an hour later I stood silently in the communicating door watching him. His concentration was intense, he breathed excitedly and - schools being different in those days - I found later this was the first time he had the magic of colour in his hands. Every day the Clinic was open he came, and slowly began to talk. By that time I knew his attendance at school was erratic and all efforts to improve this had been defeated by his silence under questioning. We made a pact together: more regular attendance at school on the days and times the Clinic was not open, and fresh paints and painting books when he came. It was from the school we heard later that a different boy had slowly emerged - complaints against him ceased. One day he brought a young friend with him and we knew we were winning our way in the neighbourhood. Constantine Gras making a mosaic, with from left to right: red beacon, tower from black to green to no colour; myself draped in those colours; and a key, a set of arrows pointing to me, the tower and Thérèsa as witness to the mosaic. "I felt I needed something in addition to the tower and me. I don't know what it is. Maybe it's a signpost trying to direct me or others, but everything is shifting apart again over time. Then I step back and look beyond the tower and me. I want to get a sense of the overall space and how these objects function within that space. Can I possibly create something that is aesthetically or emotionally satisfying? I am trying to make a work of art. I'm not sure if that is right." "Yes. You are an artist. You cannot escape that." "I was hoping that I might, but I don't think so." "You won't be able to escape yourself, will you!" "No. No." At Play In The Ruins: A Lost Generation

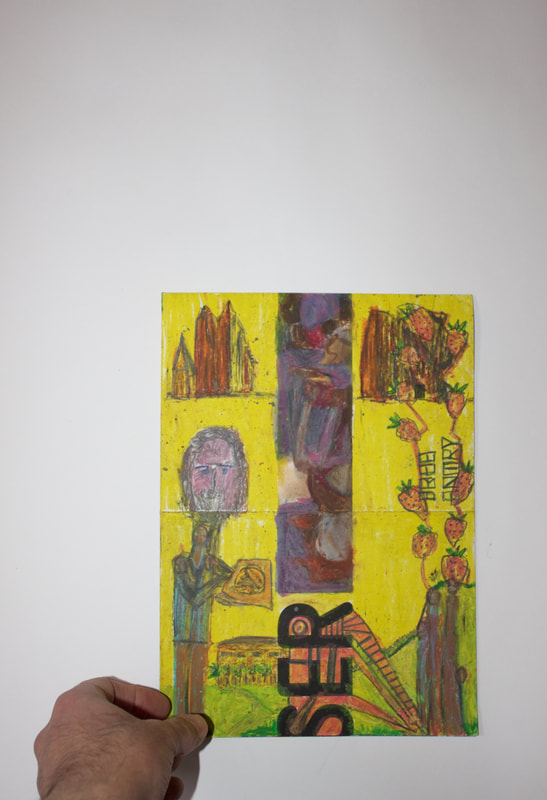

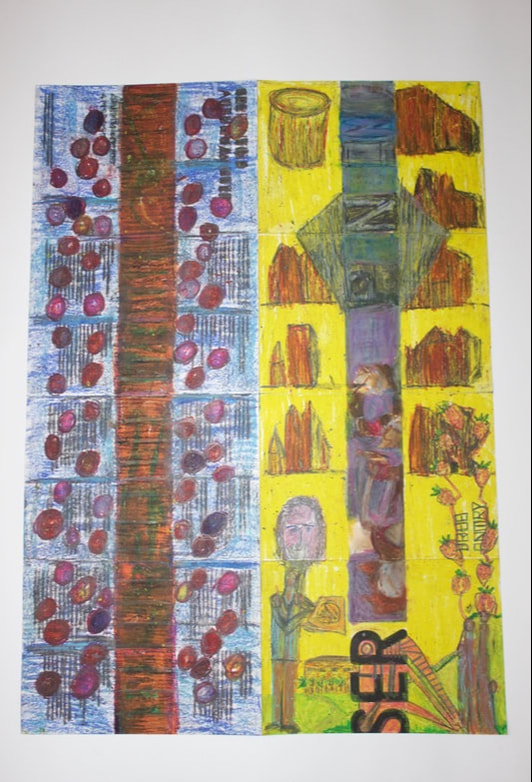

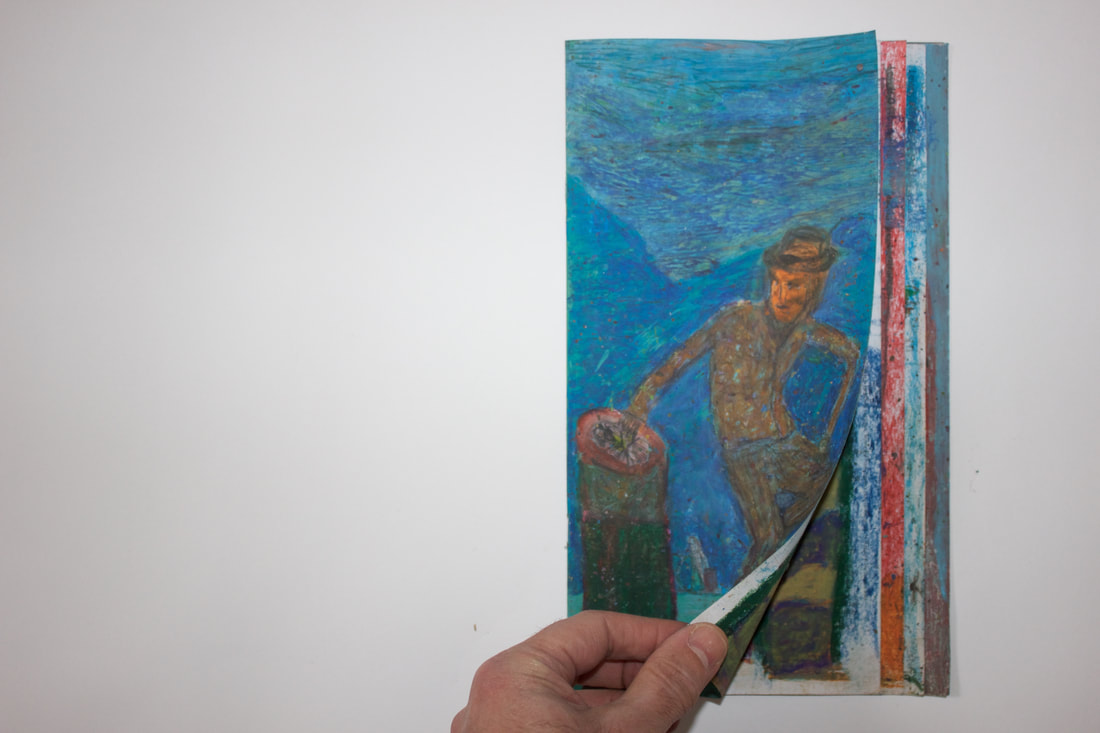

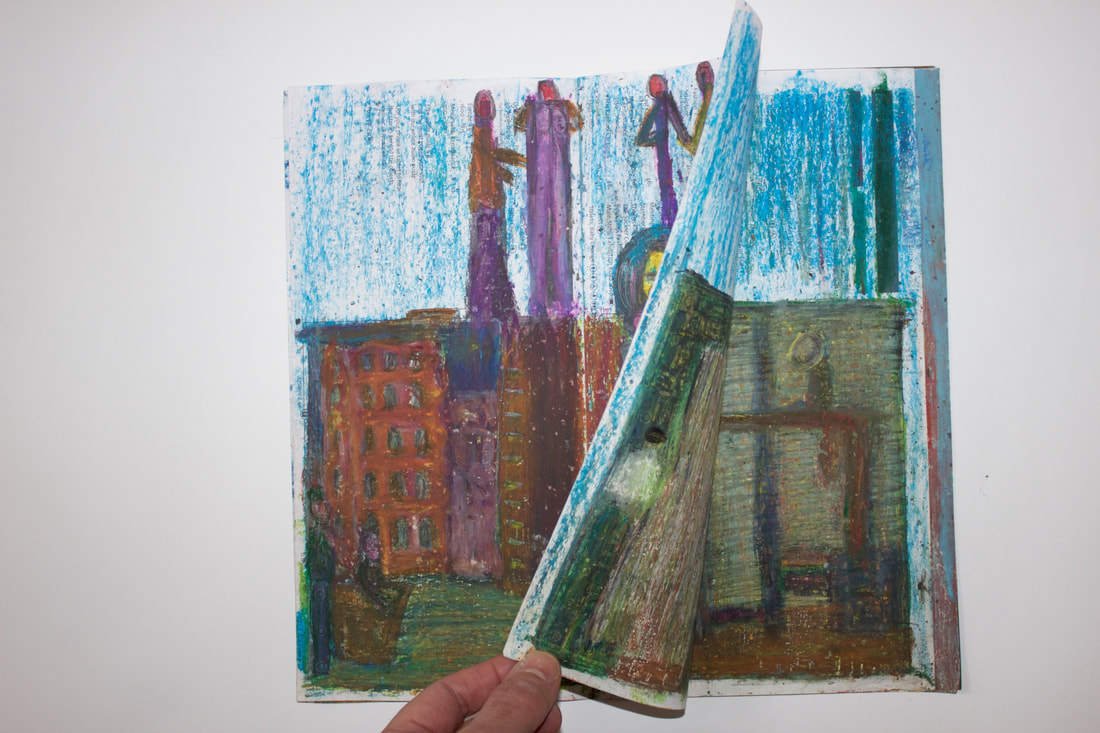

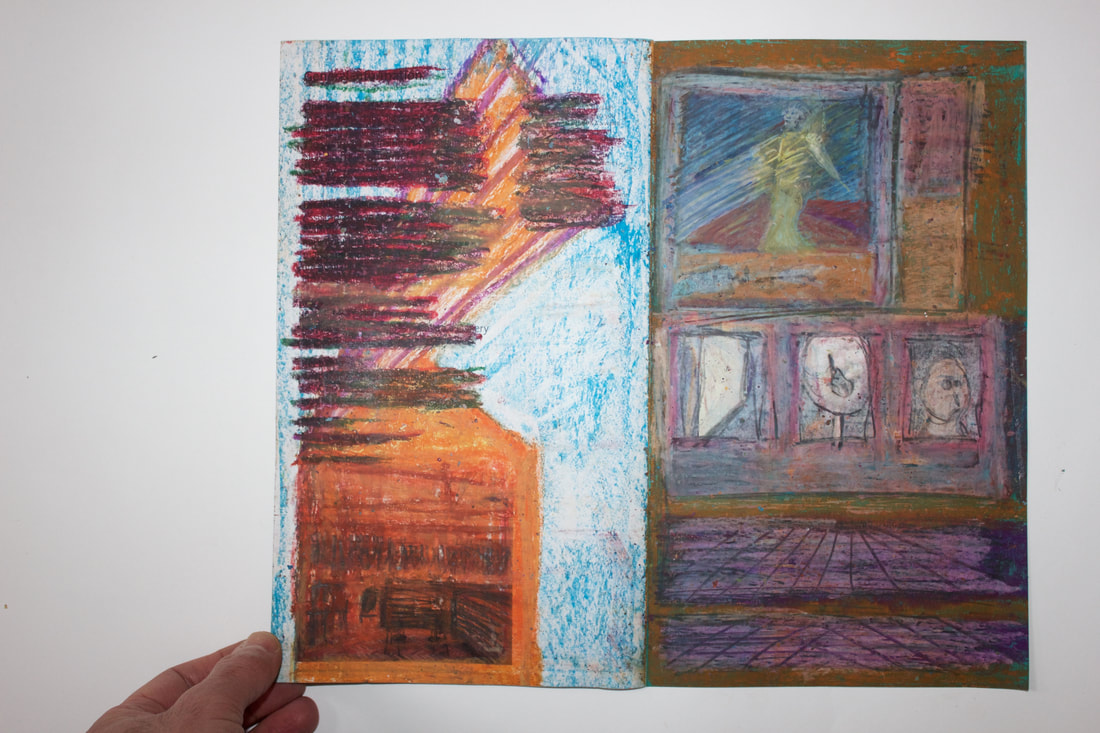

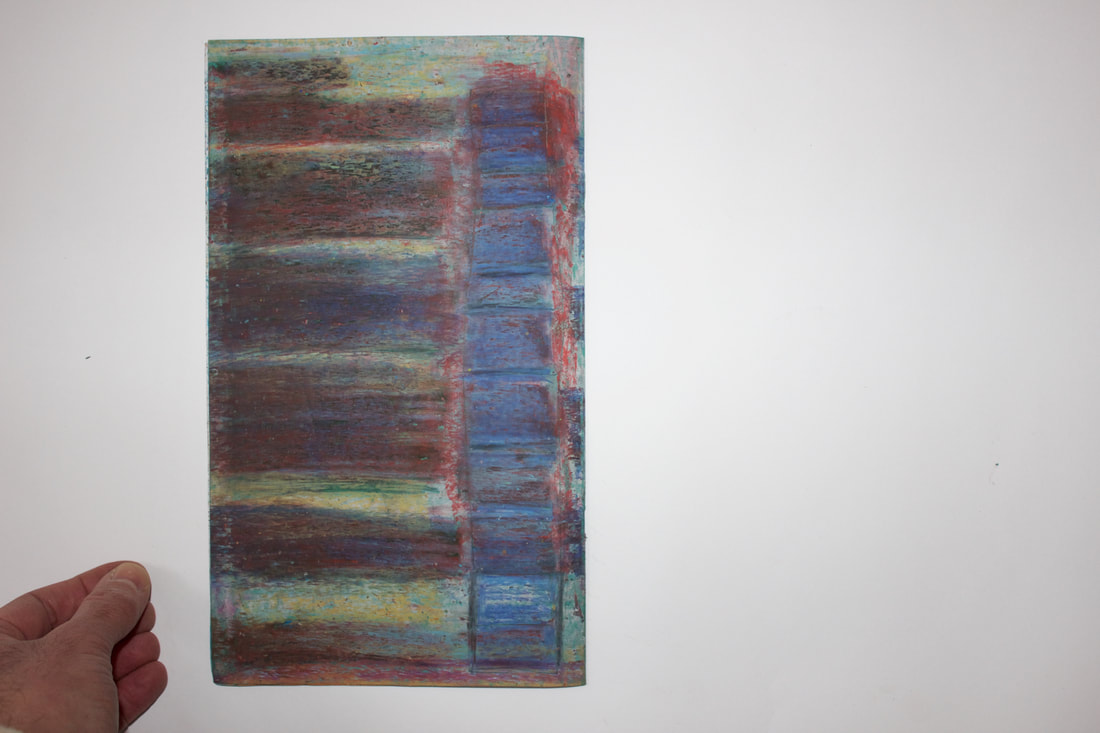

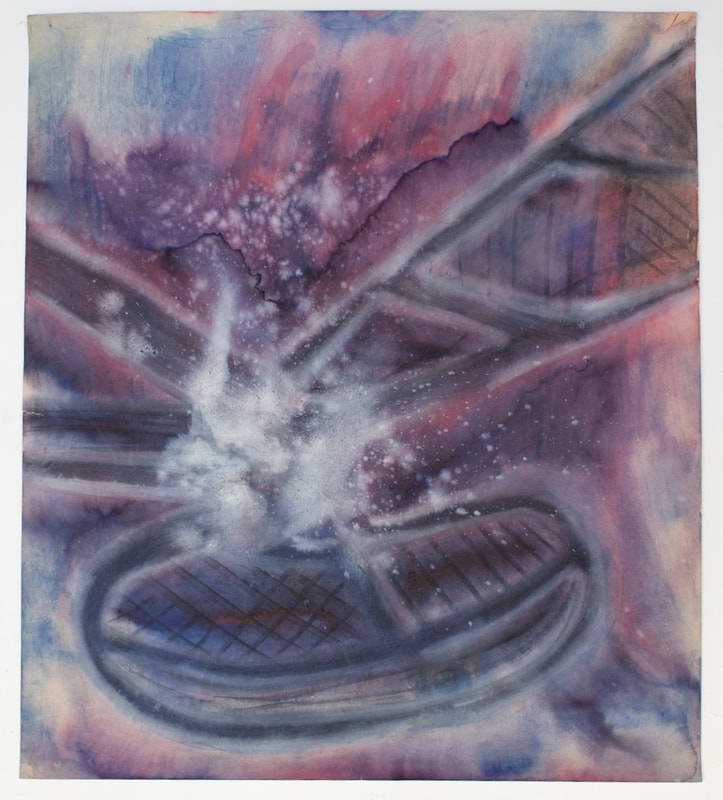

oil pastels, 33x24" 19 Dec 2016 Artist's comments on the reverse of the drawing: Starting off with abstraction, but thoughts turned to Lowenfeld sand play (Sand Face in the picture) and childhood. The news on the following day. The battle and now the desperate evacuation of Aleppo in Syria. One of the defining media images of the year, Osman Daqneesh pulled from the bombed building. His haunting stillness in the midst of horror. A pack of 8 art cards are shuffled and dealt out to the players. Maybe they are more like Tarot cards, predicting a narrative of past-present-future. What do you see? Please feel free to re-arrange the order and tell me a story or mood. My game was conceived while researching and viewing Charlie Chaplin movies. Also editing a short dramatic film about an aged tree and hard earth. I'm running both silent and sound moving pictures in my mind. I wonder if these drawings represent a parallel universe I travelled through last week. One where I filmed a dance under the Vaults on Leake Street. Searched for a tabby called Doorkins Magnificat at Southwark Cathedral. Laughed in Bay 56 under the Westway in a space re-claimed by the community. Cried during the Grenfell public inquiry held at Millennium Gloucester Hotel. Dance, search, laugh, cry. I may be the author of this game, but recall that chant - La mort de l'auteur. Shuffle the pack, deal the card, play the game. Booklet for Stewart Wallace, 2018 Oil pastel and pencil on paper Folded paper: 8 inches by 11.5 inches Unfolded paper 16 inches by 23 inches I suppose it was inevitable, as I return back to work with residents on the estates around Grenfell, that my own private art work would move in a corresponding pattern. Since the new year, I have made two artist's books. The first, featured above, is dedicated to Stewart Wallace, the community gardener at Lancaster West estate. This is a fold out book that consists of 3 separate images drawn with oil pastels and pencil. The title page has Stewart in his garden, his sanctuary. He invites me back at Easter to see the full fruits of his labours when the strawberries and raspberries will come into season. I have visualised this in the yellow pages of the book. Stewart has his back bent to the soil and tries to avoid looking up as he lives in the shadow of the burnt out Grenfell. Image two in the fold out section of this book, illustrates the tower with 71 spherical objects, each one representing an adult and child and unborn baby, that died as a result of the fire. On the reverse side of this double-image page is a darkened abstraction. It might be a space inside one of the flats of that tower block. It seems to still flicker and pulse as if there is an after glow from the fire that can never be extinguished. There is a legal and societal search to find meaning and identity in this now truly Brutalist architectural ruin. Are there any fragments left of tooth enamel? Can this domestic object be reunited with the survivors and bereaved? I fold back the pages of the book and put it into storage. I wonder what Stewart will make of this booklet when I show him. The second book, while having more of a traditional structure of pages (hence no fold out and fold back challenge), is actually far more complicated to read. It's a book I've made for myself. You might think the author would be in control of every aspect of the image making. Sorry! The world of my art does not operate in this fashion at this moment in time. I can only offer tentative dream-like suggestions and hope you, the viewer-reader, can make positive or negative connections that might offer some resolution to the narrative. Beyond the strawberry patch, perhaps you can help me decide what is the future? Or will there always be an artistic enigma to the tragedy of Grenfell? Untitled cover page: This is me dressed as an artist But what am I leaning on or pushing away from? Pages 2-3: we have cut to another time, but the blue prevails 4 media images of Grenfell projected in rapid succession - where are we? Pg 5: I knock on the front door of a flat on the 21st floor Who restored my hair, yellowed my face and gave me pink earrings? Page 4: No one can answer my knock, the family who live here are on holiday Why does page 4 not precede page 5 and what are these new buildings? Pg 6-7: I see my face briefly glimpsed in the metallic panel of a lift Are we going up or down or passing through new pipe work? Pg 8-9: I have drifted in an out of consciousness, but have arrived Who are these two strangers wanting to dance with me? Pg 10: The sun sets at the end of empire building (after Turner) Pg 11: I am dancing alone across a square Are you happy to dance or sad as the empire ends? Pg 12: The End Or is this a new beginning? Booklet for Constantine Gras, 2018 Oil pastel and pencil on paper 7x11.5 inches The Future Sound of London Acrylic paint, charcoal, inks 22 x 25 inches, 1995 There I was in 1995 projecting into the future with an acrylic painting, titled, The Future Sound of London (image above). And here I am in 2018 looking into the past with this drawing titled, The Past Sound of London (image below). Each image was started on New Year's Eve in those respective years with an ambient musical soundtrack playing in the background. Life Forms by, yes, you should have guessed it, The Future Sound of London (FSOL). That music sounds as fresh as the day it was recorded. It still has the power to unlock hypnotic grooves of improvisation. I am struggling to recollect the circumstances in which that first painting was composed. I had moved back to London following my post-grad burn out in Wales and was attempting to act out Tracey Emin's advice for an artist, get yourself a well paid part-time job, but one that you don't like too much. I was making art only for myself: my first solo exhibition was three years away, thinking about full time art and devising art projects at least a decade in the offing. Taking documentary style photographs and then retreating into the dark room was my bread and butter. Politically, Britain was ripe for a sea change after a long period of moribund Tory rule. We were on the brink of the Blair years which gave Young British Artists in London a fashionable sheen, the mirage of you never had it so good. I sense in the abstract brush work an optimistic desire to go with the flow. I had not really made a mark as a public artist. Now in 2017 that has moved into 2018, after the promise and failure of successive governments (can it be anything other?), I am working full time as an artist and devise my own multi-layered projects. I haven't used paint for years and drawing as an aid to thinking or constructing filmic and narrative potentialities, seems to be the order of the day. The drawings now are a body of work, rather than just isolated images. I'm not necessarily certain they are any better than those first steps, but have a different contextual meaning and community reading. In the latest drawing, there is more of an organic, biomorphic sense of being. The architecture of regeneration and gentrification, that has plagued me over the past few years, is no doubt encoded in the DNA of this image. Although it looks back onto the 1995 drawing, it also peers nervously into the future of an ever growing and unstable London landscape. The faces of people come in and out of focus in this vision of past present future. But their identities are confused as the British main land redraws its European boundaries. This drawing was started just before attending a gig at the Coronet, I was dancing my way into the sketch, all the opening marks made by a process of dance like movement, following the flow of the soundscape created by FSOL. Ironically, that playful orientation was being rendered in a locked down state. I was expressing a niche living in London. There is a corporate feel to these new interlocking shapes as compared with the original. The uber rich or well off are increasingly at the centre and suburbs. That green space is a gated commodity. I sense residents and us artists struggling to situate ourselves and finding a space for being, opportunities for expressing, ways of connecting to an audience or patrons. This is a hyperactive, wired up landscape. The impact of the world wide web and social media is one of the most decisive social change since 1997. So while that darkroom is still there, increasingly my art will be experienced on digital platforms like this or more likely a screenshot that is recycled elsewhere. The Past Sound of London in the Future

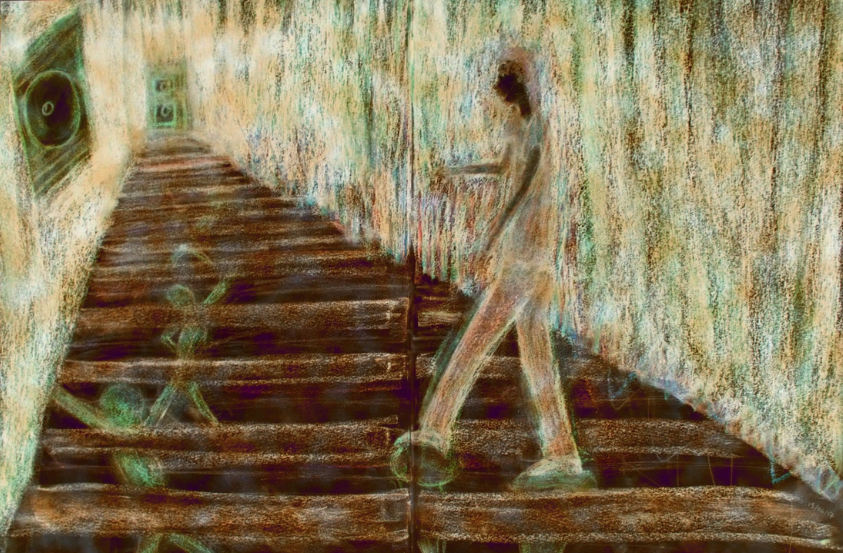

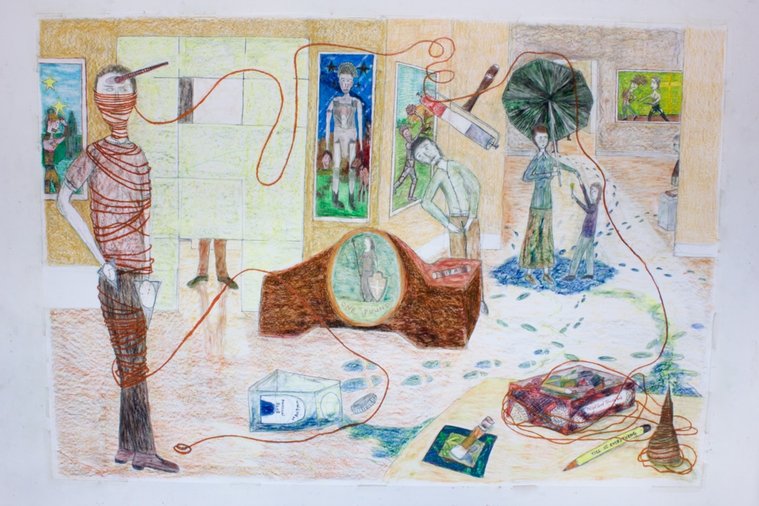

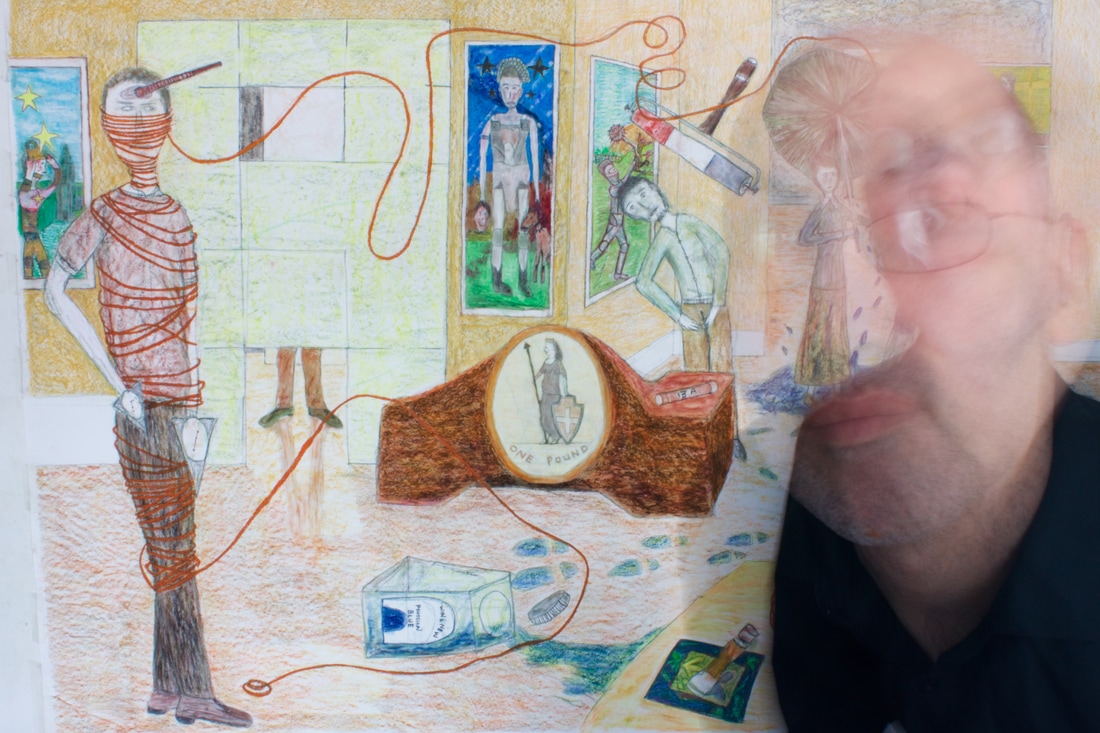

Oil pastels, pencil 51 x 73 inches, 2018 This is an arts project about the history of the Coronet Theatre from 1872-2017. The ghostly presence of a Victorian actress, Marie Henderson, will be our guiding muse. The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle will be both a performance piece and an exhibition. The play will be staged at the Coronet on the 7 November 2017. The exhibition will take place at Artworks Gallery from 11-23 November 2017 Our project is a collaboration between a visual artist, theatre director, actors and residents of Southwark. The work will be made available to future audiences by being deposited at Southwark Archives. The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle is the culmination of several years of research into the history of the Coronet. It has a deep-focus on the actress, Marie Henderson, who has hitherto been consigned to the margins of academia. Our challenge is to creatively bring her to life: the pleasures and pains, the life-pangs of a Victorian actress; one who transfixed her audiences with performances that put the oomph of drama into "melos." She will be ghost skating through our artistic timeline, materialising at pivotal moments in the history of the Coronet. This might include the WW2 Blitz and a coda section when Marie trips the light fantastic with raving clubbers. She will transport us from the age of corsets and crinoline to silicon implants, from Bedlam to Brexit and beyond. I will be using drawings as a medium to explore ideas and emotions, akin to a visual storyboard. The aim is to produce a narrative body of expressionistic imagery that responds to the architectural spaces of the Coronet and poignantly documents its final heart beat. Because our project is fundamentally sociable and public, there is the challenge of inspiring others to participate in the process of making and thinking. I look forward to sketching out the memories and experiences of people who once visited the Coronet as a cinema and those who still club today and sent into a trance with the musical beat. The icing on the cake would be discovering a senior resident, one who is over 100 years of age, who has a story to tell about the Coronet when it was a theatre. Collaborating with John Whelan and the People's Theatre Company is top of my creative agenda. John has worked on history-based community arts projects in Southwark, but probably none on this scale and ambition. The durational nature of this project will allow John and the actors to become more involved in the development of a poetic play about the history of the Coronet and even get to source their own period clothing in more nuanced detail. John and I will be exploring ideas and themes of mutual interest. For example, the origins of theatre and how this fused with music to create the melodramatic play and its link to cinematic forms of expression; my educational background was in film studies. We want to show how performance and melodrama are still relevant in contemporary society. Double bill film poster for The Crimes of Stephen Hawke and the House of Mortal Sin Melodrama meets horror, Tod Slaughter slices Pete Walker, 1930s resonates with 1970s Oil pastel, 40x64 inches, 2013 Sketching the spirits that inhabit a staircase at the Coronet, 2017 Blog entries: Shop till the zombie drops Cultural memories of the railway arches and the shopping centre at the Elephant and Castle seem ripe for melodrama and horror. Faith, Hope and Charity The life of Marie Henderson and the melodramatic play she starred in called Faith, Hope and Charity which introduced ghostly special effects on to the Victorian stage. The play is a domestic drama, with three murders, one suicide, two conflagrations, four robberies, one virtuous lawyer, 23 angels, and a ghost. Singing and sketching in the rain At the Walworth street festival on 22 July 2017, children sketch images for a scale model of the Coronet and adults talk about their memories of going to the venue when it was an ABC cinema. History and legacy of Melodrama Professor Jim Davis and Dr Janice Norwood provide a fascinating overview of melodrama's rich diversity and defining characteristics. We discover that melodrama was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the 19th century. Although it was often dismissed as a cultural product, there is a growing awareness of its importance and how it influenced both film and TV. Melodrama Workshop - Introduction We had great fun with it, as it allowed our imaginations to run riot. The only rule we followed was that each beat of the scene had to heighten dramatic tension - preferably through the means of some jaw-dropping revelation. Carolyn Cronin from the People's Company - Masks! I realised how masks conceal the wearer: you’d expect to see their eyes and mouths behind them, but you can’t – the mask itself is the focus. Interview with Sam Porter, manager at the Coronet I’ve walked around this building on my own, at night, in pitch black, with just the little fire lights on and not felt uncomfortable at all. Apart from one space. Culture and Capital at the Elephant and Castle What makes the E&C Theatre important was that melodrama was established and maintained here when other theatres either adapted to contemporary dramatic fashions or succumbed to the cinema; it even achieved a brilliant burst of fame in 1927. 82 x 56 inches. Oil pastel, pencil. 2017. Poem to a drawing Are we walking down a corridor in the National Portrait gallery? Walls lined with the great and good who have killed and conquered. This is all rather tiring and I am looking for somewhere to sit. Commotion in a room ahead, left or right? A gust of wind blows us into the Euro wing. We see a mother and child with candle and umbrella. A man checks his flies are zipped. Above his head, a tricolour ink roller in suspended animation. On the ground, footprints of Prussian blue. Centre stage, chaise lounge. What is going on? Can we sit here? Maybe in the next room, next to a woman and her copy of J. G. Ballard's The Atrocity Exhibition. In front of a painting of the British Prime Minister getting fruity with the American President. Hold on! Is that Robert Rauschenberg trapped in twine from a plumb bob? He appears to be pointing backwards and forward, one hand to 1974, the other, 2019. Can we trust an artist to TELL US EVERYTHING about this space within space That has spilled out from a box labelled Highland Shortbread? Where can I sit? My legs are killing me. Notes to myself This was sketched immediately after visiting the excellent Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at Tate Modern and during the United Kingdom government's formal notification of withdrawal from the European Union. This was also the week when The Daily Mail newspaper on March 28th featured a photo of Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon with the trivialising head line: “Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!”. On the same day, a new 12-sided £1 coin became legal tender across the UK. Pondering all these matters, I started to sketch a scene using Robert Rauschenberg as an enigmatic muse. His free and easy approach to materials, for example, building an umbrella or fan into a painted surface, had me thinking about how to use everyday objects as part of my art practice. I turned to a biscuit tin in my studio. I don't know why I started to collect objects in a biscuit tin or how long they have accumulated (more than a decade now), but this box with random objects ranging from coins, fuses, tea coaster, plumb bob, pencil emblazoned with "Tell me everything," was raided for inspiration and incorporated into the drawing. This was my equivalent to Rauschenberg's "combine" although I have made no concession to three dimensionality. There is added irony in that the box has a culinary connection with Scotland; a nation destined to have a falling out with the English over the issue of falling out of Europe. All these objects and related ideas came tumbling out of the box and into the composition. Some other allusions for the cultural critic to register:

As we march towards the spring Equinox Clouds blink and then cry outside my West London skyline. Faint rays of light bend through the veiled window of my studio. In a mere ten minutes, a dull tone of grey pastel takes a walk With confident, improvised strokes. As I step back and view, Lautreamont comes to mind: "As beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine And an umbrella on an operating table." I step forward and substitute that sewing machine for a tattoo machine. There is also no need for an umbrella as the clouds have dissolved in real time. On the picture plane, we have a domestic interior looking out across suburbia. A machine vibrates and draws blood. This is a cottage industry of body art. Bobbins your uncle! Notes:

Bobbin's your uncle!

56x82 inches. Oil pastel. 2017. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed