|

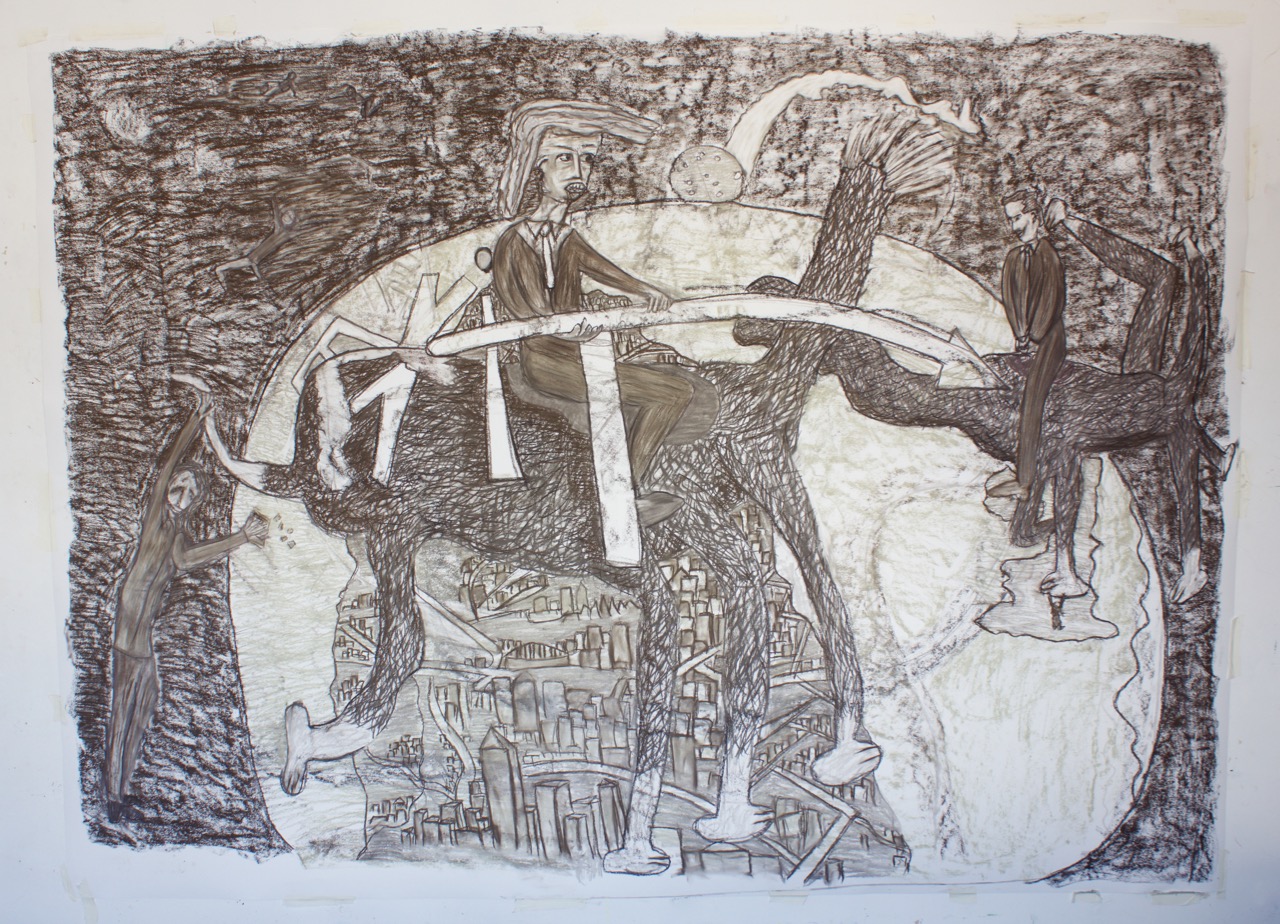

A New World Order Pastel drawing, 60x81", 2016 The Grand Christmas Comic Pantomine At the mythic Elephant and Castle Theatre Boxing Day, December 26th, 1876 Entitled Trump and Farage; Or Harlequin Progress And the Knight that fought and gained the day Characters Donnie Trump ------- performed by Miss Marie Henderson A powerful and scheming knight in love with Nigella and himself Nigella Farage ------- performed by Mr Walter Grisdale Mistress from Ing - Land who whip lashes her Euro body politic Hilaricious Clinton ------- performed by Miss Clara Griffith Deposed Queen trapped in the world wide web Theresa Maypole ------ performed by Mr Watty Bruton The titular head of state who is forever Brexiting, stage right. A production on a grand scale with thrilling scenes: Donnie and Nigella riding the headless horse of the apocalypse; Hilaricious hanging onto the tale of the headless horse; And Theresa, trying to exit stage right, but being trampled under horse hoof. All told, a magical transformation. This new world order has to be seen to be believed! Trump and Farage has been expressly sketched for this theatre by Constance Graf. Stage notes: 1. Pantomine is a type of musical comedy performed in the United Kingdom, generally during the Christmas festive period. It has gender-bending roles and a story loosely based on a fairy or folk tale. 2. Henderson, Griffith, Grisdale and Bruton formed the cast of the Elephant and Castle Theatre company in London between 1875-1880. Marie Henderson was also the directress of the company. 3. If you want to sample a pantomime, here is a link to Valentine and Orson. This text was written in 1877 by Charles Merion and is his third adaption of the medieval romance tale about twin brothers abandoned at birth, one raised in the royal court and the other in the woods. Another version was the first play performed at the Elephant and Castle Theatre when that was opened for business in 1872. The theatre building is now the Coronet Club and this is due for demolition in early 2018 as part of the regeneration of the Elephant and Castle area.

0 Comments

With my eyes closed, I sense her presence and hear a faint murmur, a sound that cascades into a tune.

This is an overdubbed improvisation in memory of Marie Henderson. A footnote in British theatre history, but in her time (1860-1880) and place (Royal Colosseum, Britannia and Elephant and Castle Theatres) she was a potent force in the world of melodrama. This orchestration celebrates the public and private life of Marie Henderson. The first section evokes the power of her performance in the smash hit of 1863: Faith, Hope and Charity. Marie plays Faith, a young clerical widow, cheated out of a property lease and who dies of a broken heart. She returns to haunt the treacherous aristocrat. He repeatedly stabs her image, but as with all good ghosts, she cannot be vanquished. This production employed the latest technological craze of the Victorian stage - Professor Pepper's optical illusion for stage ghosts. Glockenspiel and bells strike notes of tension or release, delicate or harsh surfaces that play off harp, French horn, strings and clarinet. For the finale, we find Marie Henderson in 1882 acting out her death. The actress had contracted syphillis (undiagnosed at the time) and ended her days in Bedlam Hospital with her husband by her side. An electric guitar sets the otherworldly tempo and is a poignant farewell to a theatrical force that had once captured the imagination of Liverpool and London theatre goers. I feel a tremendous affinity with the psychological soundscapes of Nordic music. Reference points for this composition are Sibelius 5th symphony and ECM Records Terje Rypal's Avskjed. Detailed blog entry on Marie Henderson.

The search for Marie Henderson

I'm on a quest to re-discover a Victorian actress. She was born in 1841 at Daventry and called Mary Henderson. Twenty years later she married in Liverpool and became Mary Geogheghan. Closing the chapter on her life, Marie Aubrey died in 1882 at Bethlem Hospital, London. The woman that I'm bringing to life is Marie Henderson, the name she adopted for the stage. She can be fleetingly observed in numerous archive records, most notably the Era newspaper. I must be careful not to idolise or idealise. Marie Henderson would have been familiar with adulation from stage struck girls in East End and Surrey: perhaps sensing in the actress, the potential for freedom of expression lacking in their lives. Also subject to the male Victorian gaze. One that often assumed an actress was grafted from the loin of the prostitute. So what does our Marie Henderson look like? This is my overriding research aim. I naively believe that unearthing her photo will allow me to gauge her existential being. That the chemicals on the surface of paper will atomise her soul. Allow her to speak (without words) and contradict all that has hitherto been published about her: not much, disjointed, man talk. Surely she must have posed for a carte de visit, during the 1860s or more likely 1870s, when based in London and at the peak of her powers? The photograph in the slideshow above was purchased from a collector and had me temporarily excited. Foolish boy! It soon transpired the photo was not my (excuse my possessivess) Marie Henderson. It is a contemporary actress with the exact stage name. The V&A Museum Collections identified the photo as Mrs George Rignold. Further research would reveal confusing correspondence in the Victorian press about the two ladies. Can the editor please tell me how Miss Marie Henderson can appear in two different theatre productions on the same night? Ode to social media. Marie Henderson would be forced to take out a notice in 1875: "Miss Henderson (the popular Surrey favourite, and late of Britannia, Princess’s, Adelphi, Astley’s, Surrey, &c.) begs to state that she appears only at the above theatre nightly." At the moment I am relatively free to imagine what Marie Henderson looks, thinks and sounds like. I can construct an image of an attractive lady perhaps powdered to hide a birth mark on her left cheek. Born into a working-class and itinerant background that revolved around the rapidly expanding world of Victorian theatre. Through talent, hard graft and networking skills, she would become one of the leading exponents of expressive acting that represented the best of melodrama; an equal of any actress to be found in fashionable West End. Her powerhouse performances would reduce audiences to tears. Even stiff-collared, middle class theatre critics were enraptured. Being of Irish or Scottish ethnic origin, our English rose has a thistle or shamrock at heart. Let me describe her life in five acts. Distinct biographical phases that compress thousands of theatrical roles, first observed in childhood, later performed on the stage. Her life tells us much about Victorian society: the world of theatre, the role of women, commerce, ethnicity and politics. The key text for study is Tracy C Davis: Actresses as Working Women: Their Social Identity in Victorian Culture, 2002. Act 1: The curtain rises to reveal a girl waiting in the wings. 1840's-1860s. Although her early years are shrouded in mystery, we can trace her backwards from the 1861 census. Mary Henderson was born of Irish or Scottish parentage in 1841 at Daventry, Northamptonshire. Her parents or grandparents would have migrated to England, one or two generations before the impact of the Irish potato famine in the 1840s. I suspect her father was Thomas W. Henderson; comedian, actor and possibly theatre costume supplier. We might be observing him in legal transcripts from 1846, accused of stealing £50 during an amateur production of Julius Caesar at the Bower Saloon in London. Found not guilty, he would be dashing off to Dover for his next job. Mary would have followed her parents as they roamed England from one theatre engagement to another. Mary would start acting on the stage from early years; no Victorian qualms about using children as labour in the marketplace and a pattern Mary would later repeat with her two daughters. The financial insecurity of working in the profession might have made for a difficult childhood, but exposed her to a myriad of experiences that could be stored in the memory bank. Theatre engendered a lifestyle that was a little rough round the Christian edges of society. Above all, It offered space for an imaginative girl to play act. Act 2: The apprentice years at the Royal Colosseum Theatre, Liverpool. 1861-1866. Liverpool was at the height of its imperial and trading power. It was a magnet in the North for Irish and Scottish migrants, looking for work and better opportunities in the industrial cities; a port of call before further emigration to Australia or America. One can see the Henderson's arriving here for work; there is no mention of Mary's mother in the archives and one assumes separation or death. The theatre listings for Liverpool provide an outline of Mary Henderson's early career on the stage; she would only adopt the name Marie when establishing herself in London. She has joined the Royal Colosseum repertory company in a building that was formerly a Unitarian chapel and ringed by a graveyard. Mary made an immediate impact in "sensation" dramas as the heroine who might be thrown by the villain from a rock into a pool of water; cue extras wriggling like waves under a blue tarpaulin sheet. She would be working at the theatre with her husband, Frederick Geogheghan. He was a violinist who composed and orchestrated music for several of her melodramas. Irish melodrama, often with a political subtext, were extremely popular at this time. Mary would play the lead roles in many of these plays: Kathleen Mavourneen; Ireland As It Was; Norah Creina; The Whiteboys, Na Bouchaleen Bawn or Ireland in 98. To get a flavour, here is a link to a recent production of Colleen Bawn. Mary Henderson's most celebrated role was as the ghost in the hit play from 1863 called The Widow and Orphans: Faith, Hope and Charity. This was the first of several spectral dramas that used mirrors to create haunting optical illusions. It was also named after its inventor, Professor Pepper's Ghost. Here is a memorable summary of The Widow and Orphans from The Mercury Newspaper, 21st July, 1863: "It is a domestic drama, with three murders, one suicide, two conflagrations, four robberies, one virtuous lawyer, 23 angels, and a ghost. There are three heroines in the piece, Faith, Hope and Charity - the first, an elderly lady, widow of a clergyman, and in straitened circumstances; and the other two, her daughters, pretty and poor, and of course models of perfection, as indicated by the label. The plot turns upon the possession of the lease of a house which Sir Gilbert Northlaw, a proud and scheming baronet, class representative of the bloated aristocracy, has acquired by fraud from the clerical widow." Act 3: Leading member of Britannia theatre and freelance star, 1867-1874. Mary Henderson moved down to London with her family in 1867 and joined the repertory company of the Britannia Theatre in Hotxon. The Sunday Times in Dec 1867 noticed the new kid on the block: “Possessed of a pleasing appearance, some command of passion and clear pronounciation, this lady is likely to become a very great favourite.†Sarah Lane, actress and proprietor of the Britannia was an important role model for the ambitious Mary (or should we now call her, Marie Henderson). There is a vivid portrait of the theatre in The Britannia Diaries: Selections from the Diaries of Frederick C. Wilton, 1863-75, Society for Theatre Research, 1992. Health and family commitments permitting, Marie would be appearing in a new production every week; only rarely did a play run for several weeks. She was cast as the young heroine experiencing moral and emotional dilemmas. Occasionally she would flex her muscles and play Shakespeare. There was also scope for cross-dressing into male roles. Here's a brief sample of character parts she performed at the Britannia during this period: 1. Ellen Morton in The Dark Side of the Metropolis; written by William Travers. The plot revolves around a country orphan who is lured to London for sex trafficking. "Miss Henderson’s acting, which is always good, was in this case all the more striking and gratifying, as she had to depict maidenly purity remaining unsullied in the midst of hateful vice." Era newspaper, 17th May 1868. 2. Florence Ashton in The Pace That Kills, (or Fast Life and Noble Life), written by C H Hazelwood. On her wedding day, a former lover turns up and wrecks havoc. "Great praise is due to Miss Henderson for the able manner in which she represents both the affectionate gentleness and surprising energy of the young, lovely and tired wife. It seemed astonishing that one so apparently delicate should act with the power and impressiveness which she exhibited when representing Florence as excited with a determination to foil and punish the man who had wronged her." Era, 13th March, 1870. In the archives we have a revealing account of the sacred and profane in Miss Marie Henderson. On the 12th July, 1869 she has travelled with 400 people and the preacher Alfred Gliddon (running a temporary chapel service at the Britannia theatre on Sundays), on a train from Moorgate-street station to an orchard in Hayes. A procession of hymns, sermons, music, tea, cake, hams, bread and butter would follow. Marie Henderson was the icing. She made a speech to the assembled folk about the virtues of appreciation, comprehension and imitation; singing the praise of Mr Gliddon and the Christian ethic. She concluded by making a prophetic statement (and more of that prophecy later): "We have a proverb which says that from a little mending cometh great ease. Many poor cast-down creatures may apply this to their morals as well as to their clothes. But I fear I am trespassing upon your time, and you will accuse me of making too great an elongation of my speech. My sex is reputed for fondness of talking, but you must forgive me. If ladies ever get into Parliament, whatever will the poor men do to keep pace with our tongues?" This is the only time in the archive that Marie Henderson speaks in her own words, admittedly performing a theatrically inclined spiritual service. Two weeks later we have accounts of rebellion, sexual shenanigans and inebriation. Frederick C Wilton notes in his diary for July 29th 1869, that Marie Henderson is refusing to play the role of Juliet (in Shakespeare) when a fellow actor (possibly a lover) is threatened with dismissal. On the following day, the diarist notes how Marie was performing on stage while under the influence and fell off a platform, blaming the carpenters for their shoddy work. Marie Henderson as diva? Why not! By 1871 she is able to pull in a packed house in an abridged version of Hamlet (playing the role of the Prince of Denmark). I suspect she was getting itchy feet and wanting to play bigger (not necessarily better) parts. A desire to transcend the Britannia rep and launch herself as a freelance actress. The re-opening of the Astley Amphitheatre (home to equestrian drama) in 1871 provided the opportunity for blockbuster roles, better pay and elevated status. In the space of a season she showcased her athleticism and physical charms. Marie was selected to play the Amazon Queen in The Last of the Race (or Warrior Women), fronting an army of 100 Amazon fighters dressed in feminised armour, or should that read amour. This was followed by the role of St. George in the big budget pantomime of Lady Godiva and no doubt testing the limits of censorship. Her concluding role at Astley's was in a revival of Mazeppa (or The Wild Horse of Tartary). An equestrian spectacle with real cataracts of water and a troupe of warring Arabs on a battle field. Centre stage we have Marie Henderson as Mazeppa. In Byron's original poem, Mazeppa is a male lover punished by being tied naked to a wild horse that gallops across the countryside. Sadly no photos of Marie, but check out the risqué Ada Isaacs Menken as Mazeppa in 1864. "Miss Henderson is an actress of considerable spirit, and possesses admirable elocutionary powers. Added to these qualifications we have the fact that she has a handsome figure, and we have said enough to assure our readers that in her they will find a very attractive, a very daring, and a very accomplished hero, who is likely to make the perilous journey and to brace the dangers of the plains of Tartary for many weeks to come in presence of thousands of ardent and applauding admirers." Era: 10th March 1872. Act 4: Boom, bust and ashes at the Elephant and Castle Theatre, 1875-1880. The freelance years had given Marie the confidence and experience to call her own shots. The lease to the Elephant and Castle Theatre was taken in 1875 and she established herself as lead actress and directress. John Aubrey, her second husband, would run the business. Marie used her extensive contacts and build a top-notch repertory company with a rolling programme of star actors. "The E&C Theatre appears to thrive under the direction of Miss Marie Henderson, who, in addition to talents, which are enthusiastically recognised on the Surrey side of the water, has evidently good ideas on the subject of management, and succeeds in attracting good audiences by giving them the dramatic fare suited to their taste." Era, 22/08/75. Marie would mount several Irish melodramas: The Shinghawn (1875), Moyna-a-Roon (1875), The Banshee, Spirit of the Borcen (1876), Gra-Gal-Machree (1876) and Home Rule (1880). Critics would note the "pathetic" power of her acting and the close bond established with a predominantly working-class audience: "Here comes Eveleen (in The Banshee), as one walking in her sleep and soliloquising, the audience becoming almost literally spellbound. The vociferous cheers which rewarded the artist were thoroughly well deserved." Era, 12/03/76. Marie Henderson would also make bold decisions about casting actors from ethnically diverse backgrounds. The Mexican and Afro-American tragedians, Don Edgardo and Samuel Morgan Smith, had successful runs at the Elephant and Castle playing in a range of classical and melodramatic roles. "Mr Morgan Smith was called before the curtain and greeted with unstinted applause. We put aside the questions of race and training. What is good is good, whether we find it in a Hindoo, a Chinese of a native of Fiji. Happily such narrow prejudices have passed away, and we were glad to perceive the audience listening with attention and giving the performer fair play. There were no more interruptions than there would have been if a white man had appeared as Othello. We must not admit to compliment Mr Morgan Smith upon the tenderness and warmth of feeling displayed in the scenes with Desdemona, a part which, as played by Miss Marie Henderson received its due importance throughout the play." Era, 24/10/75. British society and theatre in the 1870s would have a complex relationship with issues of race and ethnic identity. Racist stereotyping would be an accepted norm. This is illustrated by a wonderful write-up, cum send-up of The Wild Flower of the Prairie produced by Marie Henderson and Mr Frank Fuller in 1877: "If cheers, and tears, and laughter are to be taken as indications of success, it was in every respect successful. What better elements of success we should like to know could be supplied for melodrama than the doings of a pretty Indian girl; a couple of villains who are ever ready to “do†if not to die; a lonely spot where a catatact comes bubbling and foaming; a hero who is bound hand and foot, and, after a terrible combat is left to die; a heroine who comes in the nick of time to rescue him; pistol shots; oaths; appeals to heaven; thunder and lighting; limelight; a war dance; Ha Ha’’s in abunance; a legacy of vengence; hate; revenge; curdling Indian blood; Spanish vengence; threats of visits from the grave; beetling brows; daggers; gunpowder; coloured faces; big boots; hoarse vehemence; a comical Negress; an Irishman who is persuaded to turn “Nigger†in order to watch over the interests of his master; bludgeons; bleedings; blightings; blows and brooms; “Canons of Death’ (that is the name found for one of the scenes); blood stained pages; noble sacrifices; fights for life; moments of peril; and striking denouments. All these are to be found in The Wild Flower of the Prairie." "Miss Marie Henderson, looking bewitchingly picturesque, created a profound impression as Lupah, the wild flower of the prairie. Everything this lady attempts is marked by great intelligence, much grace, and more than ordinary histrionic ability." Era, 16/09/77. In March 1876, Mr and Mrs Aubrey, on a roll, took over the Royal Victoria Theatre (Old Vic). She was once again director and would rotate her appearances at both venues. The Royal Victoria initially started with Shakespeare, but would also add variety to the programme before homing in on the box-office pull of melodrama; but running both theatres was financially unsustainable. A fire that completely destroyed the Elephant and Castle Theatre on March 26th, 1878 would downgrade the aspirational fortunes of the Aubreys. No lives were lost, but the scenery, dresses and fixtures were uninsured. The Royal Victoria had to be given up, A charitable relief fund was set up to support the Elephant repertory company. Marie Aubrey would return to productions at her old stomping ground, the Britannia. It would take more than a year, with escalating costs, to rebuild the Elephant and Castle Theatre. It opened on 31st May 1879 with a melodrama called Raised From The Ashes. Several critics at the time saw the disastrous fire as the cause of Marie's mental health problems. During the following seasons, Marie Henderson would become an infrequent performer on the stage. Business was never the same. John Aubrey would appear in the London Bankruptcy Court in 1880 filing for a petition of liquidation. His liabilities were estimated at £2,600 and assets £300. The Aubrey reign at the Elephant and Castle Theatre came to an end. On 22nd August 1880, Mr Aubrey fired his last salvo in the press. "I have to inform you that I am still in possession of the premises, and that a motion for an injunction to restrain Mr Hosford, the landlord, from interfering with my proprietorship is now pending in the Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice." The court order was overturned on appeal and the theatre was opened by new management on 3rd October 1880. Act 5: Paralysis of the Insane and last performance at Bethlem Hospital, 1881-1882. The reputation and identity of Marie Henderson would now be fought out in the press and medical establishment. Rev. F. Statham of St. Peter's Church, Walworth published a letter inviting charitable funds to support the actress. "I take the liberty, through you of soliciting for the sufferer the sympathies of the Dramatic Profession generally. It is that of Miss Marie Henderson, the wife of Mr J. Aubrey, late lessee and manager of the E&C theatre. Through the loss of her wardrobe, etc, in the total destruction of that theatre by fire in the spring of 1878, and through more recent reverses, her mind received so severe a shock that she gradually lost her reason, and at the present time she is totally unable to resume her professional duties, and, in accordance with the doctor’s certificate, which, I append, there seems little chance of her ever being able to do so." Era, 26/03/81. This would spark off a vicious correspondence in the press. A former actor at the Elephant and Castle, Walter Grisdale, who had a falling out with the Aubrey's, published a counter-response. Marie Henderson was not deserving of charity. He claimed that during the recent fire, money raised by public subscription wasn't adequately distributed to the actors and technicians, but lined the pockets of the Aubreys. There was limited scientific understanding of the neurological complications of Marie's condition. The stigma of "madness" would frame discussion about mental health and brain disease. H. H. B. Wilkinson: "Her view of ordinary things was defective and uncertain, owing to impairment of the reasoning faculty. She was, even at the period of which I speak, nothing more than a cipher in society." Era, 23/04/81. Marie Henderson who once had complete mastery of hundreds of characters and voices in British melodrama, was now reduced to monosyllabic utterances: "yes" and "jolly" and "oh dear." We can poignantly recall that prophetic speech made to a crowd assembled in Hayes. The one concerning "morals" and "clothes" and a "fondness for talking." Her husband describes the delusions of his wife, thinking she was a great lady (possibly a character from one of her plays) and constantly dressing herself over and over. Instinctively, Marie held close to the theatrical costumes that once gave shape to her power of communication. Money was eventually raised and she was sent to Bethlem (Bedlam) Hospital. The medial records for Marie Henderson's stay at Bethlem tell the true story. She is finally diagnosed: Paralysis of the Insane. Full understanding and treatment of this disease, one caused by a sexually transmitted infection, syphilis, would only become available from 1910 and with advances in antibiotics. Marie Aubrey died on 10th of April 1882. She is buried in an unmarked grave at Brompton Cemetery, grid reference AE/245.3/39. Artistic considerations On the 4th March 1877, onstage at the Elephant and Castle Theatre, an oil portrait was presented to Marie Henderson. The portrait of herself was inscribed with the following: "Presented to Miss Marie Henderson by a few friends and admirers of histrionic art.†Does that portrait still exist as a family heirloom? Perhaps gathering dust in an attic. The Geoghegan's are rightfully proud of their family folk tree, but only reference their link with Henderson in passing. I wonder if Marie Henderson once sang the ditties penned by her father-in-law, Joseph Bryan Geoghegan: "Ye haven't an arm, ye haven't a leg, hurroo, hurroo Ye haven't an arm, ye haven't a leg, hurroo, hurroo Ye haven't an arm, ye haven't a leg Ye're an armless, boneless, chickenless egg Ye'll have to be put with a bowl out to beg Oh Johnny I hardly knew ye." Marie Henderson. I re-invoke you in word and oil pastel and film. Who would I cast to play you? You would have to be an unknown. Humour me, as I imagine presenting a script to the magisterial Max Ophuls, my all-time fave film maker. He would do justice to a biopic based on Marie's life. I see his endlessly tracking camera following a lady in the fog as she crosses the busy roundabout at the Elephant and Castle, dodging, perilously, trams and horses. Gathering her pace. Tracking past iron railings and lamp posts. The shouting of costermongers selling fruit or oysters. She drops a programme sheet. Does not care. Breathlessly reaching the front door of the theatre. It is locked. There is a CLOSED TILL FURTHER NOTICE sign. This could be 1927, 1935 or 1974. Previous blog entries have outlined how theatre becomes cinema and melodrama morphs into horror at the Elephant and Castle. The actor, Tod Slaughter, playing the stage and screen roles of Sweeney Todd has a blood line to Marie Henderson's heart of melodrama. Sheila Keith in British horror flicks has a related vein of passion. The concept of "horror" may seem connected with world wars and cinema of the twentieth century. However, ladies and gentlemen. Before horror, let us feast on melodrama: with sensational plots, exciting scenic devices, brazen displays of flesh and emotion - all embodied in the life and times of our heroine, Marie Henderson. A previous blog about 1970s British film culture and the horror genre was a point of entry for my art project. Today, I'm going to freeze frame on performance and iconography in horror. Then rewind 100 years and connect with melodrama. There is a site-specific location binding these themes: the Elephant and Castle Theatre, Cinema, Club. On one level, this is about the ghostly memory of a building that is currently the Coronet Club at 28 New Kent Road. Bringing it to life, I need to dip your toes in the archive and employ some creative sleight of hand. Built in 1872, the Elephant and Castle Theatre closely followed the opening of the E&C station on the London, Chatham and Dover railway line; the theatre bulging around and under the arches of the railway line. Urbanisation coupled with increased shopping and entertainment attractions would lead to the area being called the "Piccadilly of South London." The theatre was established by maverick businessman, Edward Tyrell Smith; he's another story waiting to be told. He saw money to be made from his love of theatre. However boom and bust would haunt every theatre even as this one regularly packed in the local working classes with a programme of weekly melodrama and seasonal pantomime. In the face of stringent health and safety requirements from the London County Council, the building was sold off and converted into a cinema in the early 1930s. Another cycle. Another fifty plus years of cinema in vogue and then decline. The cinema finally closing its doors in 1999. The Coronet club was christened in 2003. There is a new phase of contested regeneration taking place at the Elephant and Castle. The social housing and shopping centre is being replaced by new forms of private housing, shops and business. At the time of writing, I don't know if the writing is on the wall for the Coronet Club. Let us hope that it has at least another 100 years to entertain. So as I zip around in space and time, let me transport you (once again) to the ABC Elephant and Castle. The auditorium is in semi-darkness. The camera tracks across row after row of empty seats. A projector beams into life and reveals a couple sat at the back. She in hot pants, him in tightly crocheted flares. They are on a date. He hopes the horror and sex double bill will facilitate intimacy. She is anxiously waiting for the first move. They almost have the auditorium to themselves apart from an old geezer in the front row fumbling about in a bag and then cracking open some monkey nuts. They are all in for a shock. Frightmare (1974) is being screened. Shirley and Deepak are watching the film with growing consternation as several off-camera murders culminate in the bloody use of a power tool on a corpse; this D.I.Y predates Texas Chainsaw. Then forty seven minutes into the film, the first dramatised murder. Shirl and Dee are gripped. They might later reflect on how the writing (David McGillivray), acting (Sheila Keith), filming (Peter Jessop), music (Stanley Myers), all come together in a memorable construction of cinematic horror. This is what they see and feel. A vulnerable young lady, Delilah, has arrived for a tarot card reading at the country home of Dorothy. The latter has been shown to be a senior citizen with the craving for flesh; hence the corpses and bloody packages delivered by her daughter. Fear the worse! The soundtrack however starts with the reassuring chime of a carriage clock and a flickering fire place. The comforts of pastoral domesticity. Conversation about what the future holds is interrupted by the rustle of a curtain. Dorothy's animalistic qualities then come to the fore. She ominously refers to the little squirrels in the house. Deliah has money and tarot cards thrown in her face and tries to escape. The demonic laugh of Dorothy, licking her lips with perverted excitement is a classic echo of melodrama (more of this anon). The chime is now replaced by frenzied percussion and dissonant orchestral chords. S and D as spectators are implicated in the alternating close-up, face to face, point of view shots of Dorothy and Deliah: steam hissing from the red-hot poker, blood issuing from the mouth, the rictus of horror. Don't try copping-off with this! Aside from the aesthetics, we might want to briefly consider the ideological impact of a horror film like Frightmare. Robin Wood in his influential essay, An Introduction to the American Horror Film, argues that the best types of horror film tap into political, cultural, and sexual issues. Horror is not just about goose bumps, but can explore complex ideas about the nature of society and its inequalities. The monster as the "return of the repressed." This reading is very pertinent to the films of George A Romero; take Dawn of the Dead, with both zombies and plain old humans consumed by the mania of a shopping complex. For Frightmare, director, Pete Walker and his scriptwriter were keen on "making mischief" by embedding their film with a subtext that was probably drawn from the pages of the Daily Mail. The film loosely dramatises the question - should not the most serious offenders be locked up for good. Dorothy is able to carry on her cannibalism as a consequence of a legal and medical judgement about being fit for society. This is a topical debate; not the cannibalism, but recidivism. The film likewise makes the male lead a do-gooding medical professional. He sucks. Or rather has his brain sucked out. One senses a questioning of the efficacy of psychiatry. It's a pity that Walker doesn't spend more time teasing out what the lust for flesh actually means for Dorothy apart from satisfying some primal drive. Minor quibble. Was Pete Walker conservative by nature and compelled to direct subversive films? Apparently so. With these thoughts still in mind, let me guide you to the Elephant and Castle Theatre in 1927 and 1935. Norman Carter Slaughter (1885-1956) commonly known as Tod Slaughter was an actor/manager of stage, screen, radio and T.V. who championed melodrama when it was long out of fashion. Jeffrey Richards in his book, An Alternative History of the British Cinema, 1929-1939, sees Slaughter as a missing link between the theatrical world of melodrama and the cinematic horror; a pioneer for a "cinema of excess" predating Hammer horror by several decades. Slaughter and his repertory company were based at the Elephant and Castle theatre for 3 years. 1927 was a hight point when West End audiences flocked to see his production of Maria Marten, or Murder in the Red Barn. He must have been annoyed that he wasn't acting in this production. Expected to run for one week, it was seen by over 100,000 people and bowed out after 100 performances. It generated intense debate about "blood and thunder" melodrama in the context of contemporary theatre. Alas, there is no film record of this production. But you can see Tod (below) acting in the film version made in 1935. So what would a courting couple at the Elephant and Castle make of this stage production in 1927 or the screening in 1935. They would certainly have found it difficult to get intimate in a packed, hissing and cheering theatre. Once again there would have been the shock factor, this time witnessing an execution on the stage; less effective on screen, due to censorship. The actor playing the role of William Corder, who is executed for the murder of his lover, Maria Marten (all based on real events) has a noose applied and then falls through the trap door. The brutality of the staging had audiences gasping. What about the hammy meat of Tod's acting style? It's difficult to swallow in our post-modern world, but is ripe for re-evaluation as a stylisation where the heart is worn on the sleeve. We can easily identity the broad brush strokes of melodrama: the sneer, the gesticulation, the maniacal laugh. No great psychological insight is intended. Freud need not apply. But it is very sincere and convincing. The villainous roles that Tod Slaughter became synonymous with, Sweeney Todd and William Corder, despatch opponents in a style that should remind us of modern counterparts who have a savvy, deadly punch line. Sweeney Todd uttered the line: "I'll polish you off!" Corder had this quip: "I promised to make you a bride, a bride of death!" Perhaps its best to view the acting in relation to the world of melodrama and when you respect the laws of this artistic universe, it is as natural as natural can be. My previous blog flagged up some of the Euro influences on British horror. This also applies to melodrama which emanated from French and German musical dramas in the late eighteen century. By the mid nineteenth century this had been codified into a recognisable art form extremely popular with working class audiences. We know the heightened passions and the spectacular effects of melodrama, perhaps best remembered from early silent movies: the damsel in distress, tied to a railway line, the train approaching, the hysteria, the rescue. This is typical character and plot for a Victorian melodrama. However the plays also contained much depth and elaborate stories that often reflected the political and social changes of the late 18th and early 19th century. By and large, the "return of the repressed" could represent the working class (urban or rustic) against the forces of the land owning squire or the new industrial boss. Often Irish nationalism would play out against the English. There is a sense of fatalism as characters are born in a hierarchical society. They exert themselves in a power or psychological struggle to either inherit property or find fame or misfortune (Australian gold or penal colony?) or, if you were a heroine, fending off the oily love making of the villain. Tod Slaughter's films are updated versions of plays in this tradition. They are a window onto the past. One notable exception that looks forward to Hammer horror is The Face at the Window (1939). So having cross-bred Sheila Keith and Tod Slaughter as uber serial killer, mashed up the world of horror and melodrama and teased out ideological and historical concerns - what next? Let me re-think that first one again. Sheila Keith and Tod Slaughter meet on screen, we violently cut from one to another as they unleash anarchy and challenge the social order. A wound on the surface of British culture. Prick it and watch yourself bleed. I am intrigued by how melodrama and horror offer the potential for extreme psychological states. The representation of mental health and madness. Installation? A theatrical and cinematic space that is shape shifting between the 1920s and 1970s. Reminded of other artistic interventions - Marcus Coates, A Ritual for Elephant & Castle (2012). I write this screenplay outline: Tod Slaughter, theatre impresario in dire financial straits is putting on a stage play. The bailiffs have confiscated his costumes and props. His love life is problematic; ex-wife and child acting in the wings. Tod is about to mount a last ditched melodrama, perhaps updated with gothic touches and this becomes the hit sensation of theatre land in 1927. But it all descends into a blood fest. He is stalked by a serial killer bumping off all those connected with him. Let's add a character called Alfred Hitchcock fresh from the screening of The Lodger (1927). Hitch has some interesting ideas about casting Tod in his next film. But will Tod survive the final reel when the theatre is consumed with flames? Will an older, wiser, Shirley and Deepak, be engrossed watching this as a download on their iPad? What are their memories of the Elephant and Castle? They might be interested to know that things haven't exactly changed that much. The Coronet Club is staging a Valentines party on Friday 14th February, 2014. "Discover a NAKED FEAST! Or discover your wild side in the Chambers of Venus, whilst elsewhere in the Coronet you’ll find the Onion Cellar, a chance to Voodoo your ex, or jump in a hot tub whilst watching a movie." If anyone wants to engage with these themes or ideas, please do not hesitate to contact me. I'm an artist open to collaboration. Next blog will once again shift in time, but not space. I will introduce you to the leading lady at the Elephant and Castle, the Victorian actress, Marie Henderson (1841-1882). There are at least five things you should know about her! |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed