|

Last summer I had to put Glourie House up for sale.

The damp and decay could not be maintained. Empty rooms were haunted by ghosts, the ghosts of my ancestors. They don't seem to know how to act and are afraid to confront me. I can't stand hearing the squeak of their fearful, retreating footsteps. Never once have I heard their voice. An American tycoon had opened a golf course on the coast road. Sunk in a dram of whisky, I reluctantly sold him my ghosts. It's my last day to water the plants and have high tea. Brick by brick, the house and its contents will be stripped and shipped to the States. My ghosts are going to become part of an oldie worldie theme park, yahoo. Maybe next summer they will speak to others through me.

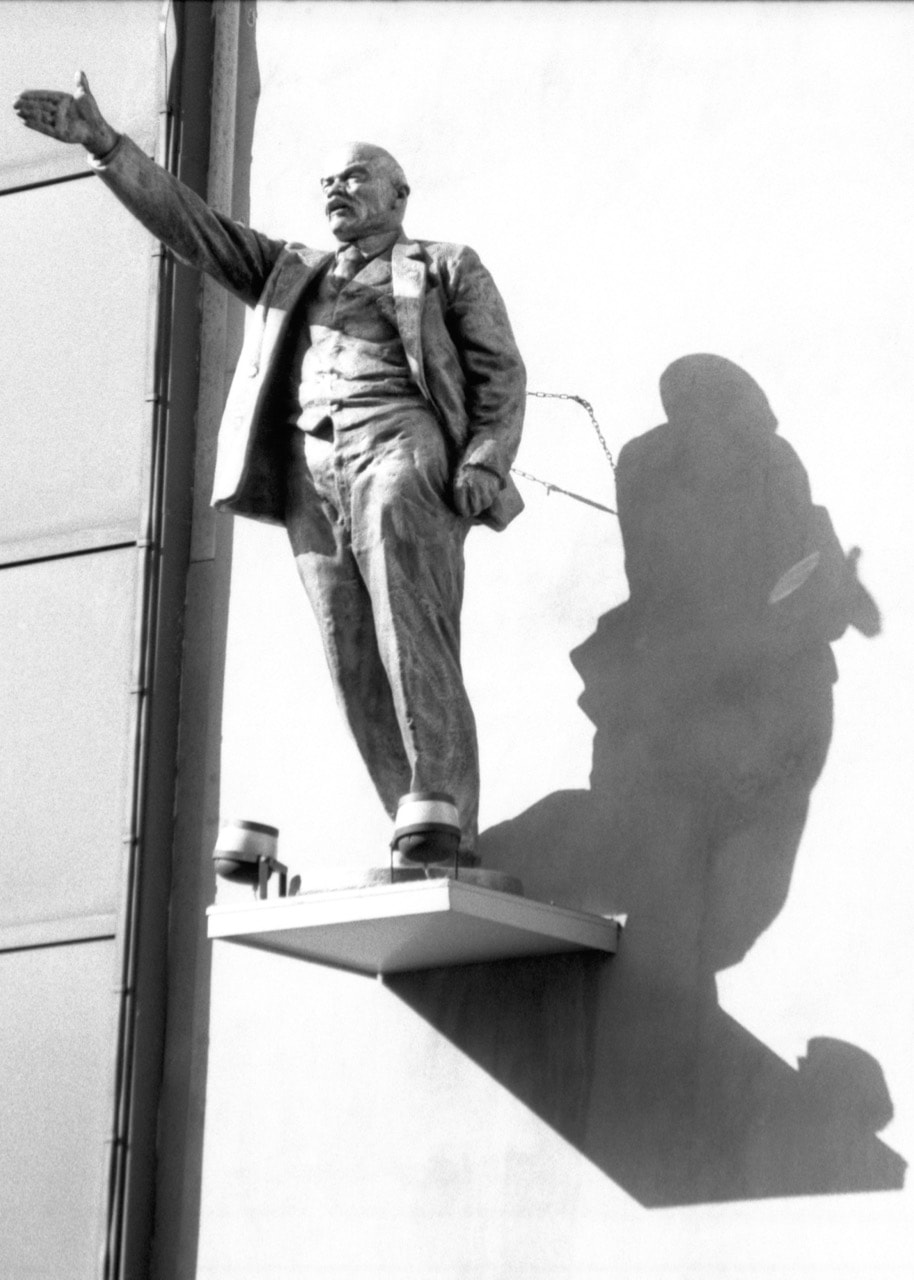

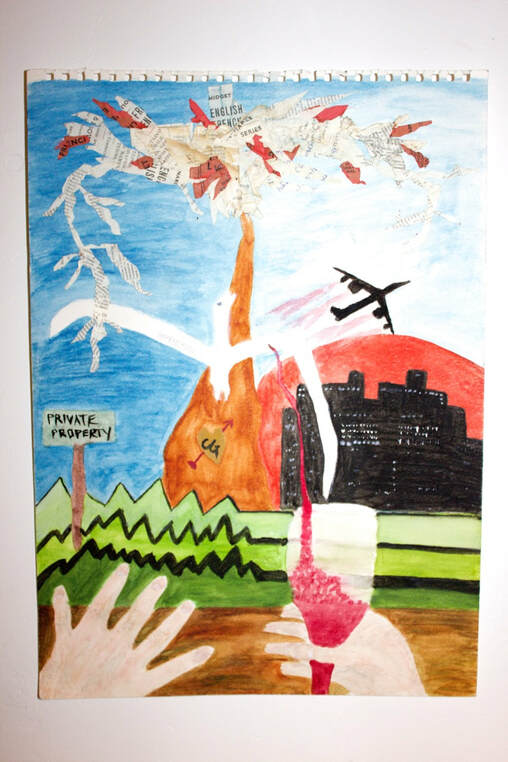

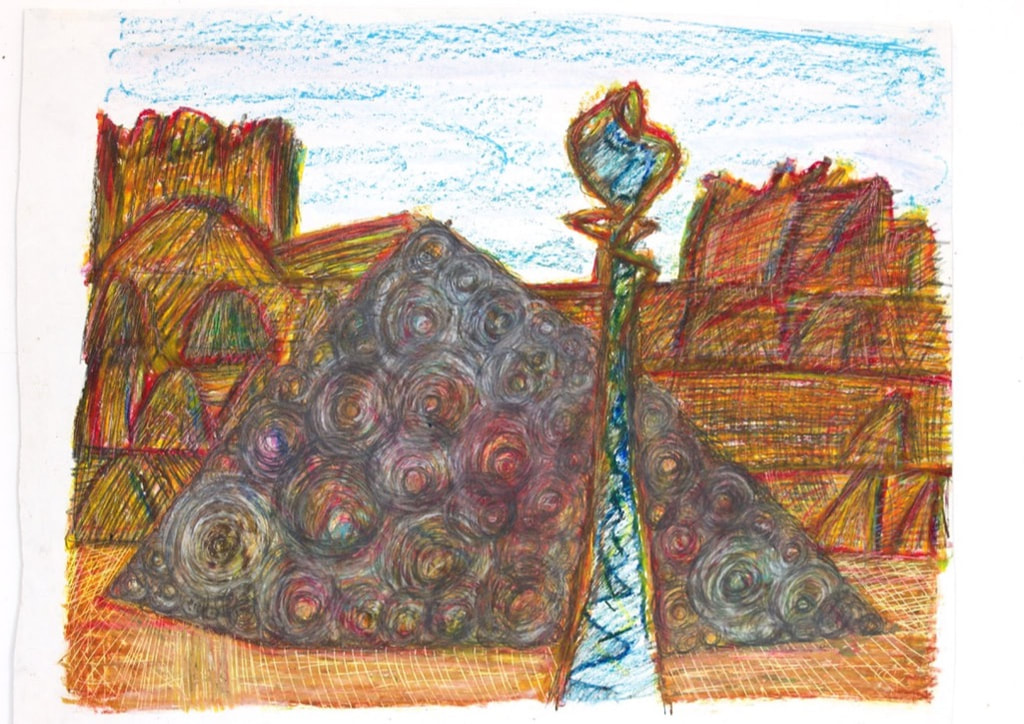

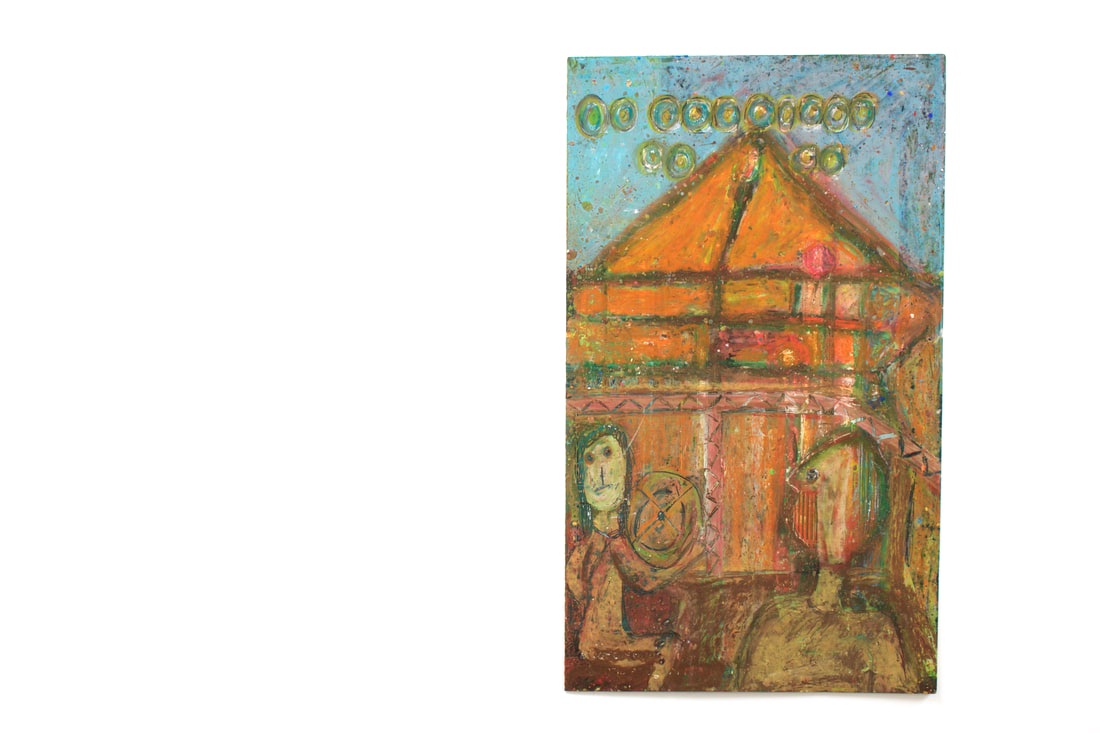

Drawing and words in creative response to The Ghost Goes West (1935), starring Robert Donat.

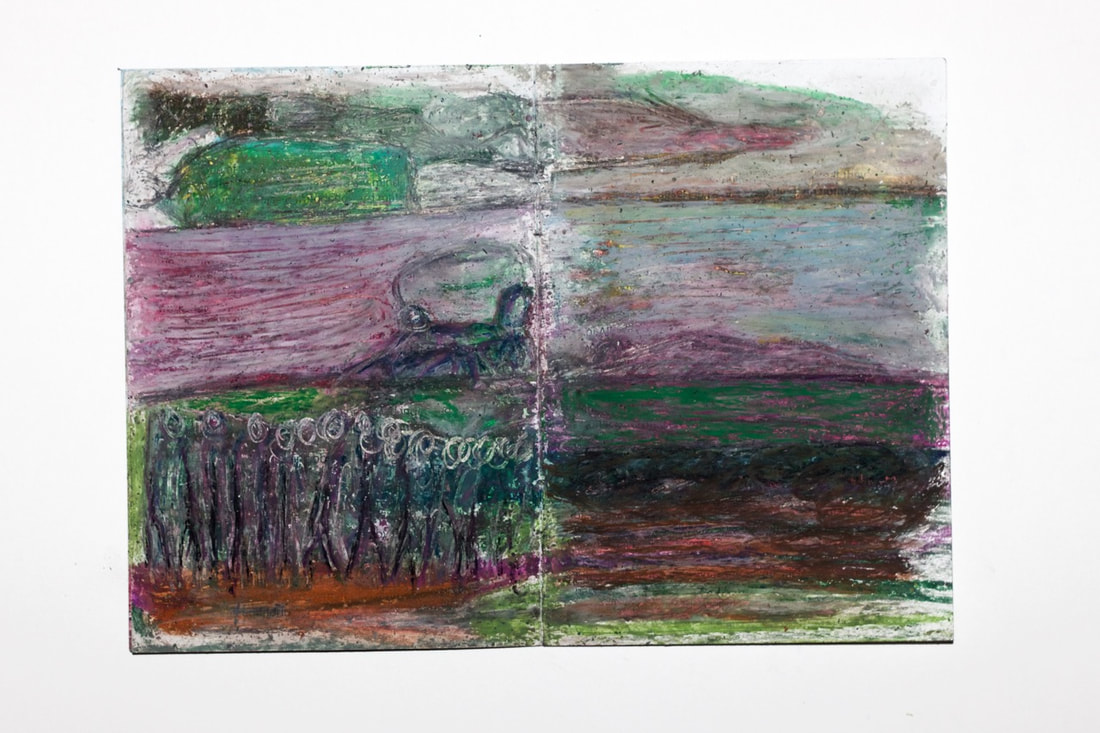

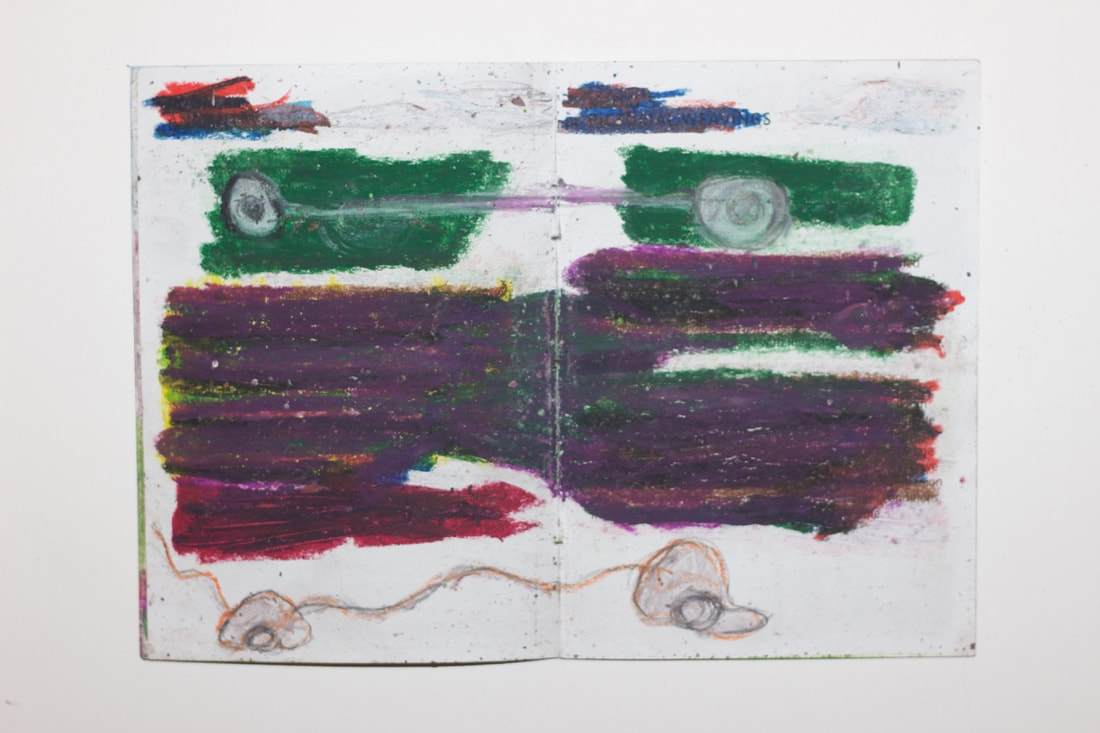

Glourie House For Sale (2019) 93x58" oil pastels

There is a voice behind the ghost and the silence of pictures: British film star, Robert Donat, 1905-1958.

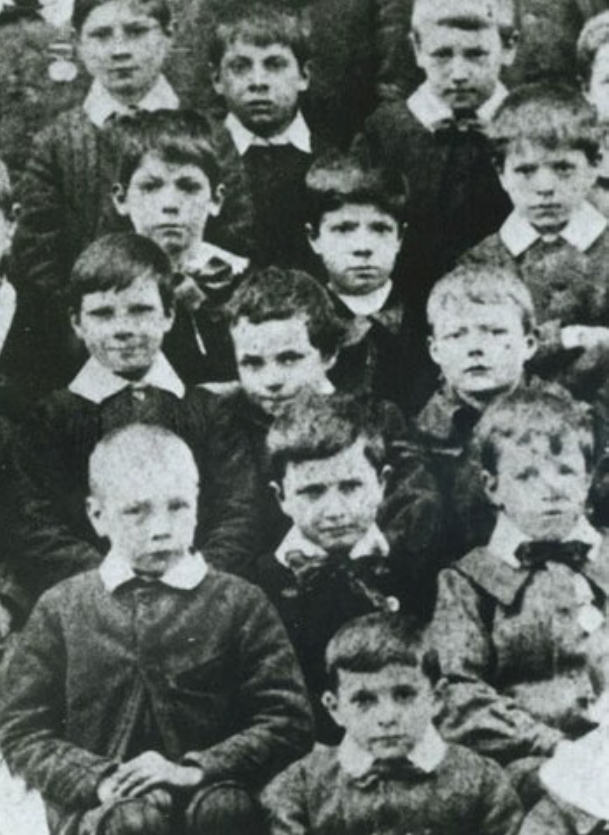

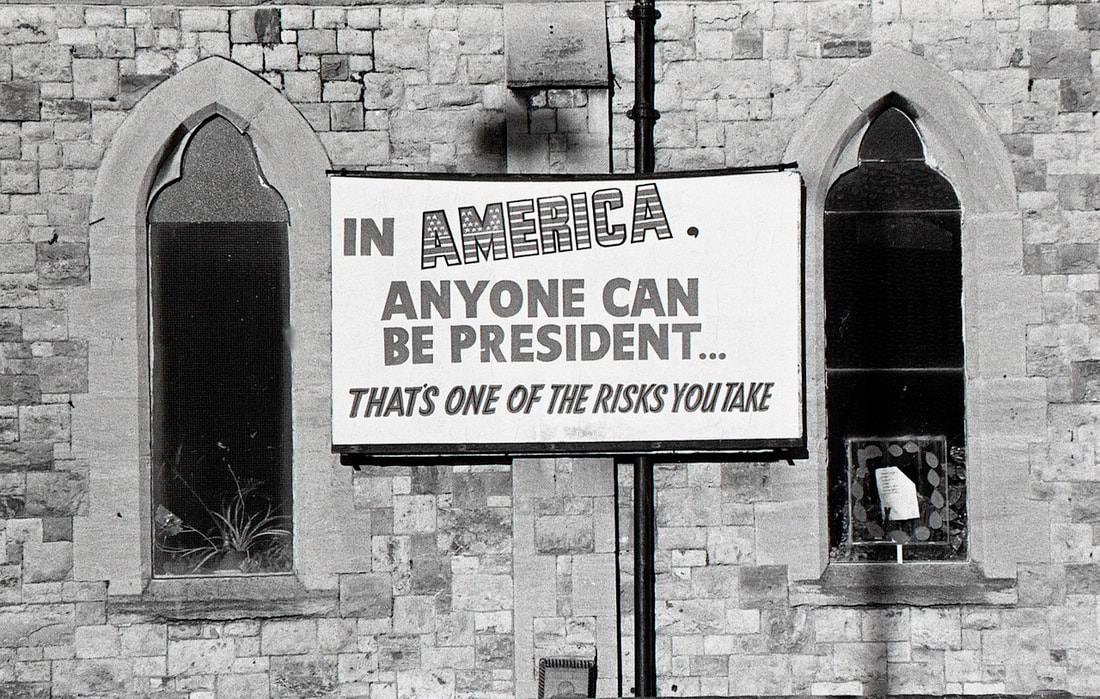

Before we get to the voice, here are a few memorable facts about this now largely forgotten actor who was so highly acclaimed in his lifetime. A poetically inclined child, Robert would recite Shakespeare in the streets and on the trams of Manchester. "Oh there goes that funny boy again, saying those queer words." A rising star of the stage, he broke into movies with a rebellious laugh. Donate had a screen test for Men of Tomorrow (1932) but the director, Leontine Sagan, thought he was a terrible ham and caused the struggling actor to break down into peels of laughter at the futility of the test. Two days later the test was seen by the head of studio, Alexander Korda. He was so impressed with the jollity that he hired Donat on a three year contract. Breaking into movies isn't usually a laughing matter. Donat made one film in America, The Count of Monte Christo, but disliked the cultural experience, and never went back. Hollywood Studio executives chased him through the courts, but Donat struck a lucrative and unique deal to have high-budget films made in England, culminating in Goodbye Mr Chips (1939) for which he won his Oscar. Several generations of American actors recognised the subtle and charismatic charm of Donat's performances. Spencer Tracy sent him a postcard applauding his decision not to work in the States; otherwise us bums would all be out of business. And then Jack Lemon commented: "The best screen actor to me, without any frigging question, was not even Spencer Tracy, but Robert Donat. And what made him so good was that he always seemed to be acting in the first take of a scene. You have the feeling he has never said those particular words before. You should have the feeling that the film was shot in sequence, even if it wasn't. You should believe that the scenes were acted in chronological order, with no embarrassing little jarring discrepancies of emotion. Robert Donat had that, too – the wonderment that made us think those things were really happening to him." Vicky Lowe describes the appeal of Donat cutting across class boundaries: "Therefore, despite being categorised through his stage work as a classical actor, alongside the likes of Gielgud and Olivier, on film, there is a palpable difference in Donat’s aural presence. Whilst nearly all of the famous stage/screen actors of the 1930s came from a comfortable (usually Southern) background, Donat is a notable exception. Michael Sanderson has researched the parentage and place of education of famous actors of the time including Charles Laughton, Leslie Banks, and Laurence Olivier. All except Donat went to either private school, university or both. Whilst his image fits in with the rest of his peer group, his voice can be interpreted in terms of its difference to his peers. His voice in this country, therefore, was recognised as being beautiful without being necessarily classified as ‘posh’: classy rather than class – bound. Kinematograph Weekly explains Donat’s vocal appeal in this way: ‘In a country of so many dialects and empire markets, spoken English should be unplaceable. […] You cannot ‘place’ Robert Donat’. ‘The best speaking voices in the world’. Robert Donat, stardom and the voice in British cinema" Vicky Lowe, 2004 I want to bring this homage bang up to date. We in Little Old England have endured several years of political chaos in a desire to shift away from the European Union in the direction of new alliances struck with America and other trading blocks. To resolve our current stalemate, we are going to have a winter General Election and another intense period of party political sound biting and speechifying. It's interesting to note, that many of Donat's characters in the movies of the 30s and 40s, in the context of that turbulent political period, have memorable set-piece speeches to deliver: whether as a politician in the Houses of Parliament (The Young Mr Pitt); or as a legal big wig (The Winslow Boy); or in The 39 Steps as Richard Hannay, on the run for his life, seeking sanctuary in a lecture hall and having to deliver an impromptu speech about Scottish politics, grouse shooting and the fisheries. So as I listen to Conservative, Labour, Liberal, Brexit, SNP and other voices, I will filter them through to one exquisite moment in the film, Knight Without Armour. As we Brits bicker and fight to play a role on the world stage, perhaps we can rewind and take a leaf out of Dietrich and Donat in this Russian Revolutionary (shades of Zhivago) saga. Dietrich is an aristocratic prisoner of war. Donate is escorting her to a trial and an unknown fate. In this memorable scene they romantically bond over the poetry of Robert Browning contemplating how to live, laugh and love, moments before a Cossack attempts to slit their throat as the scene concludes. As a cautionary footnote, Knight without Armour, ends on a rather tame note. That doesn't really matter. We often don't succeed in threading together the complex narrative of art and politics. Last summer, you could fall in love with a film star and the fragility of performance and voice.

1 Comment

Jordan Stone, film maker in conversation about his parents, Barbara and David Stone,

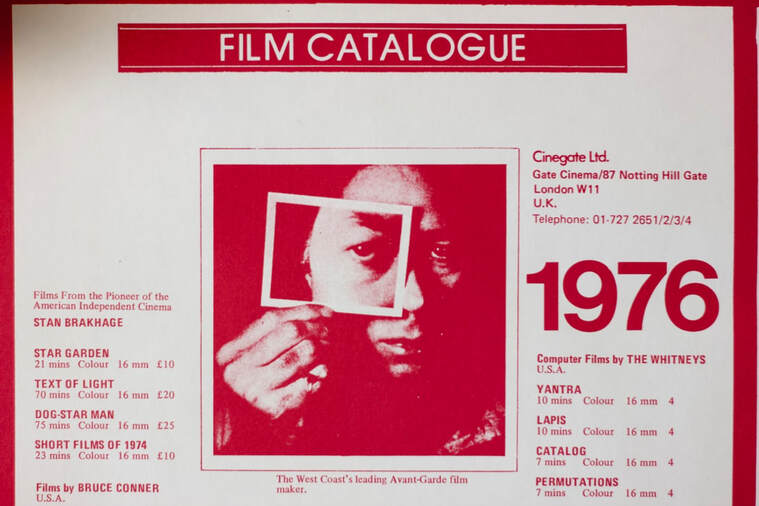

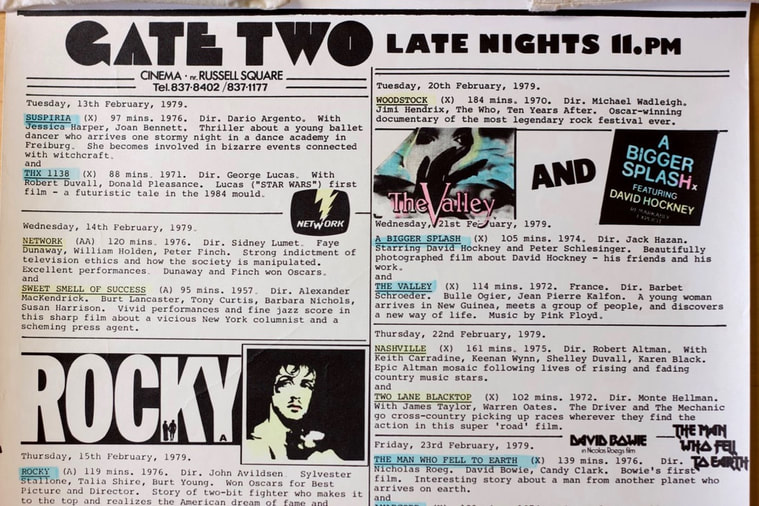

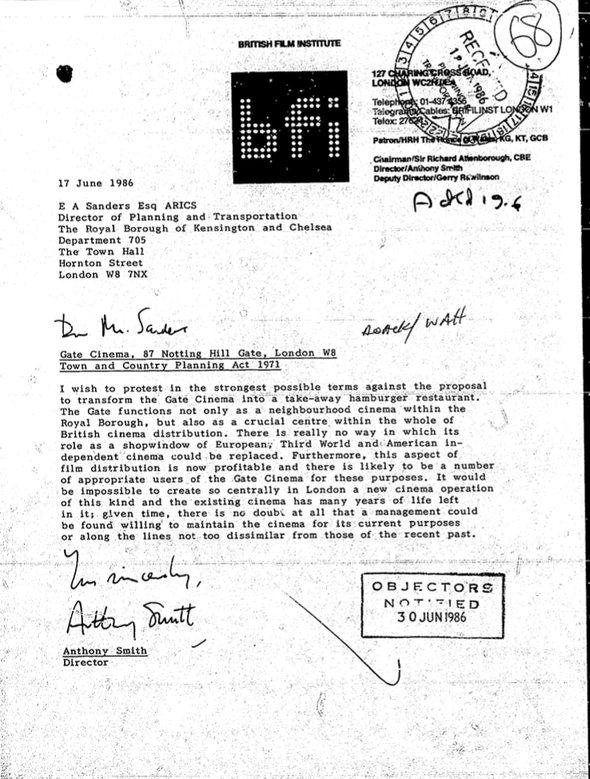

who opened a pioneering art house cinema in 1974 at the Gate, Notting Hill. The family moved to England in 1971. I think what my father originally wanted to do was to open a New York styled delicatessen in London where you could get bagels, cream cheese, smoke salmon, pastrami on rye bread. That was his original plan. But my parents had a passion for underground, avant-garde and independent cinema. They had been attending film festivals from the very early 1960s, whether it was Cannes or Venice. They were the creators of the Spoleto Film Festival in 1959. And so they were very familiar with European directors, the press, film critics, historians and writers. They had also been involved in the various film art movements in New York. They had made films themselves and also produced films with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. So at some point, they realised that there was this huge area that was missing in film exhibition and distribution. And that was their talent: to create a distribution and an outlet, a cinema, at the Gate in Notting Hill for showing these independent films. At that time films were still being dubbed for UK release. And there were films that would not have found a way out of their country of origin. My parents combined their passion with the business. But taste has to obviously come first. You have to create that and show it to the public. In America there is also a certain passive-aggressive approach to business whereas in England, it's a lot more passive. Maybe aggressive is not the right word, but they were more proactive, a term used today, but not used then. And so, it's like everything aligned at the right time. A cinema became available for them in Notting Hill. It was called the Classic. I think the previous owners couldn't afford to keep it going and that was the moment to strike as it were. What you have to realise is that the distribution company Cinegate and the Gate Cinema went together. What we distributed was what we showed. In the Cinegate catalogue, we had a huge collection of experimental cinema from Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Stan Brakage and the Mekas Brothers. And what also was remarkable were the late night double bills, mainly from other distributors, mostly American classic and cult films from the 1930s up to the 1970s. My parents created this culture of late night screenings that started at 11pm and went on till 2 or 3 in the morning. No one else was doing that. I still bump into people who tell me that they saw this film 25 times because they went to the late night program every other night. And unlike other cinemas, the Gate was open 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year including Christmas Day, New Year's Day. We were open every single day. Other cinemas started to copy us with late night programming. The Scala started doing the all-nighters at weekends. The Electric that was just down the road from us, on Portobello Road, was a repertory cinema. Peter Houghton who ran that cinema had perfect taste. It was an absolute fleapit at the time, but they created their own cult even before the Gate. But it was very different from our cinema. They would show a week of Hungarian movies and then ten days of German New Wave and then a week of Charlie Chaplin. And they showed a lot of films that we distributed that fitted perfectly into their programming. But they weren't opening movies. We were and they were independent, art house films. There is a nice little story. The Electric went through many periods of running out of money and my father insisted on lending them some. It was a real beautiful little moment unheard of that one cinema would help out another in the same area. I don't think my parents started up their operation thinking in a competitive way whatsoever as opposed to enhancing the whole concept of British Independent cinema. A few years later, once everything was going well, my parents had a good relationship with EMI and Barry Spikings, its head at the time. He had produced The Deer hunter and EMI had a cinema in Bloomsbury. But they had no idea what to do with it. They didn't know how to program it and so they gave it to my parents and the rent was completely reasonable. After a while, Gate Bloomsbury (now the Curzon Bloomsbury) was divided and had two screens. Then some short time after this, the same thing happened with Rank who had a cinema on Camden Road. My parents took that over and it became Gate 3. And finally, in the basement of a Mayfair hotel, there was this wonderful, tiny, super-exclusive cinema with just 40 or 50 seats. That became Gate Mayfair. When we first opened in Mayfair, this must have been about 1980, Mephisto, which was a huge success and went on to win Best Foreign Picture Academy Award, that was shown at Mayfair on a second run. I think it was playing for 9 months. My sister says it was shorter. But it felt longer. The majority of art house movies were definitely not American. The only American art house movies would be ones made by first time directors who sometimes had a distribution deal with a major company. And so the only way you would find out about these films was going to film festivals where the producers would be at Cannes, Venice or wherever they were trying to sell their films. My parents would be looking out for these types of films. Jonathan Demme was a Roger Corman protégé and his first couple of films we opened, I think we even distributed them. There was CB Radio and Melvin and Howard.

There were moments that brought great controversy that fed into the success and mythology of the Gate. Derek Jarman's first film, Sebastian, for example. The dialogue was in Latin and there were scenes of men making love to each other. It was definitely not pornographic, definitely an art film. But they were under a lot of pressure from the Board of Censors which was run by a guy called James Ferman, who was also an American. There wasn't much love between him and my parents. There were lines around the corner of the Gate Notting Hill because the only film prior to that which could be conceived of as a homosexual film was A Bigger Splash. That was a film about David Hockney and we ended up showing that at the late nights. But Jarman's film was a full-on feature film and made by someone we had never heard of. We had a lot of celebrities and famous people coming to see that film in 1976. And then a couple of years later with the Oshima film, In The Realm of the Senses, where you had two lovers making love throughout the film and in the end the girl cuts the man's penis off. That film was refused a rating by the Board of Censors. My parents came up with a way around this; which was to turn the cinema into a club. So people had to be 18 and pay a minimum 25p or 50 pence membership and then they could buy a ticket to see the film. But as kids growing up, we were told to stay away from the cinema because my parents were expecting to be raided by the Home Office every day. I also know that for that film to be seen, they put together a list of very well known people who had signed a petition demanding that this film be allowed to be shown to the general public. This was not just film people or from the entertainment industry, but also politicians.

The regeneration of Notting Hill had not happened at this time. That was much later. Everyone who was everyone was coming to the Gate. You had to imagine Harold Pinter living down the road and he would want to see everything. We had people who loved film and wanted to see films that the film critics were writing about and that would not otherwise have a chance in a lifetime of being released in its original form. We had punk musicians, artists and photographers, a lot of theatre people and of course, the general public.

My father was always charging a little bit more at our cinema. There was a reason for this because we were showing films exclusively. I think our first ticket price in 1974, for Fassbinder's Fear Eats The Soul that opened the cinema, was 60 pence; but after a year or two, this went up to 90 pence. And of course, we were an art-house. You were going to pay to see art. He wasn't trying to rip anyone off. It was a very exclusive approach however. And my father was actually quite short and the rows in the cinema were based on his leg- room. What he wanted to do was get as many seats in as possible. So we did have a reputation of having very thin rows, but that was based on the fact that he was quite short. I think we had 282 seats. If you look at the Gate today, my father would be surprised what it turned into with the sofas, the tables, the feeding and drinking during the film. I remember we were one of the first households that had a video projection system at home because film-makers from around the world were sending us films to watch. We grew up watching films that never made it into distribution. We had friends coming over to the house who never knew what a video was, VHS or Betamax. And we had equipment that was flown in from the states. This was set up in one of the rooms in the house, a screening room. Actually whether we lived in New York or London, my father always had a 8mm and 16mm projector set up in the house. Saturday night we would be watching films. They were very social events with film critics, Chris Petit, Nigel Andrews, David Robinson and filmmakers. We were also very friendly with someone who worked at the National Film Archives and every weekend he would come with a 16mm print under his arms, something that was 40 or 50 years old. My mother would do a big dinner and then we would all sit and watch the movie. That was a large part of the Stones' reputation. From the age of 11 or 12, I was working in the cinema and the Cinegate distribution dispatch office. Cleaning the films, packing them up and taking 16mm and 35mm prints to whoever was renting them. My brother and sister were also working with me in the cinema, making popcorn, tearing tickets and in the projection booths. I was also an actor and then at the age of 16, I had already started a video production company. Then a producer friend of ours asked if I wanted to be a runner on one of his films. That's how I started making my way up as an assistant director and have never stopped. I still am a first assistant director on feature films, commercials, and music videos. I was based in L.A. for a long time, too. And now I'm operating out of Italy. I look after a lot of the filmmakers who come to shoot here and I've turned that role into a type of service producer as well. I've produced projects with Sofia Coppola, Mike Figgis, Spike Lee. I’m a filmmaker myself. My films are not commercial and that is a result of most of my life working on other people's movies whom I've learnt so much from. The lesson that my parents ingrained in all of us is that you have to do what you feel is right - for you! And we grew up in an anti-commercial atmosphere. Anything that was American studio was the devil. We knew from the beginning that people who went to America to make films, compromised their creativity, because a producer or the studio said we want more tits and ass and more violence. However In the last 5-10 years in America, I've found that there has been a rush of films that are very independent. But most films can't be made unless they have a distribution deal. The film studios and media companies will put money into a film for its distribution rights. The filmmakers are not dictated to as badly if it’s a non-studio film because they have got the money just for distribution. So what's happened is that it's allowed much more of an independent approach to American filmmaking. There are many different structures to put a film together. You can raise money privately; you can raise money through pre-sales, through distribution sales, money from the studios, from several companies or countries. Tax incentives. It's a whole quagmire of things before you can get interest for the project. But if American studios are involved, the more control they have over the finished product. It's a different process for a European or a Chinese filmmaker. I saw a space to do commercially what my parents had done in London during the 1970s. I ended up for a while programming two cinemas in Milan in the same style as the Gate. I also created CinemaStone and this is not just a production service company, but it also dealt with film and event programming. I grew up doing what I was destined to do.

Barbara Stone Unpublished - trailer for film written and directed by Jordan and Veronica Stone

Jordan Stone's website Poster art work from the Barbara Stone Archive recently deposited at King's College, London And which will be available to view over the coming years Drawing by Constantine Gras: When a kiss fans out Watercolour, pencil, ink 9.5 x 12 inches, 1994 Link to film event called Emotion and Economics - A history of the Gate Cinema Anna Bowman: "I really enjoyed Emotion and Economics. It was great to see Adam Ritchie's film set in NY and the extract from the fascinating film about RD Laing. They were a wonderful reminder of the past and the damaged video/film just added to the atmosphere. Constantine Gras' curation was superb and the live actors, speakers and extracts of films worked really well. His film about the garden near Grenfell tower was very moving - a poetic and considered response to what happened there." This is a documentary film of an event curated by Constantine Gras that won a special distinction prize at the Portobello Film Festival, 2019. It celebrated the history of the Gate Cinema, Notting Hill, London from 1911 to the present day. A narrator told the story of emotional creativity in the world of boom and bust capitalism. A monster mash-up of films included silent shorts, extracts from the films of British film star, Robert Donat, and art house cinema of the 1970s. The Electric Palace - Silent Years (1911 - 1931) 0:00:00 Introduction by the narrator: "The cinema experience as we know it started with the opening of picture houses between 1907 and the first World War. This period saw an unprecedented investment when businessmen shed their cautious approach to risk in search of massive financial rewards." 0:01:33 Introduction by Horace Sedger, American business man who opened the Electric Palace picture house in 1911: "There are many nay-sayers, who put us down! Who think films corrupt young and impressionable minds. They say there is no future in this newfangled technology. Humbug we say! The cinema is a mere infant." 0:04:34 Extracts from silent films available to view on BFI player The Production of a Map (1917), Delhi Durbar (1911), Demonstration of Suffragettes (1910) Tilly and the Fire Engines (1911) 0:06:35 A poem written by a projectionist from the silent cinema. "I'm here in a fireproof box that is hot as a stokehole floor, And my head goes round to a clicking sound and a rickety motor's roar And my nose smells films and my tongue tastes films And my eyes they can see film too Till I'm sick unto death at the thought of films." The Embassy - The Coming of Sound (1931 - 1963) 0:08:50 Mary and Jorge visit the cinema to see a Robert Donat film. 0:10:30 Dr Victoria Lowe, University of Manchester, on Robert Donat’s "Art of acting in the age of mechanical reproduction." 0:14:14 Film extracts from Goodbye Mr Chips (1939), The 39 Steps (1935) and Knight Without Armour (1937) 0:16:07 A letter to Robert Donat from a fan: “Will meet you at midnight on Sunday outside Boots.” The Classic - A full blown repertory (1963-1974) 0:17:29 Adam Ritchie introduces the film he made in New York in 1966 with Yvette Nachimas called Room 1301: “The dangerous film stock was then destroyed, so there is no way back.” Followed by screening of film (15 minutes long). A film about a worker lost in the maze of a high rise office block. The Gate as Art House (1974 - 1985) 0:37:08 Nigel Andrews, Financial Times film critic, shares his memories of the pioneering Gate cinema in the 1970s and the American couple, Barbara and David Stone, who screened and distributed independent movies from around the world. 0:43:44 Trailer for Barbara Stone - Unpublished (Film in production) Explores the life of a mother, filmmaker, teacher, distributor and exhibitor Written and directed by Veronica and Jordan Stone 0:49:32 Extracts from Fear Eats The Soul (1974) and Sebastiane (1976) Directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Derek Jarman To The Gate Picturehouse And Beyond Anthony Smith, Director of the BFI, 1986 “I wish to protest in the strongest possible terms against the proposal to transform the Gate Cinema into a take-away hamburger restaurant.” 0:51:38 Jonathan Barnett, Director of the Portobello Film Festival, introduces his film R.D. Laing On Iona: “They were all tripping on magic mushrooms and had a go at R. D. Laing because he cancelled a seminar. And then he gave them a talk about anger and had them eating out of his hand.” Followed by screening of film (10 mins) 1:02:50 The narrator: "We have glimpsed how the history of this cinema has been shaped by pioneering figures with one eye on entertainment or art and the other on box-office takings. Managing a sustainable business in a constantly changing world. We have experienced the power of film stars and their impact on the audience. We have celebrated the history of film made on fragile celluloid stock." 1:06:05 Constantine Gras on how he curated this programme and on the concluding film, Strawberries Are For The Future, which is about the garden (and gardener, Stewart Wallace), in the shadow of Grenfell Tower - a year after the tragic fire claimed the lives of 72 people. Short extract from the film. 1:11:16 Q&A Lee Ellwood, current manager of the Gate Picturehouse Dylan Stone, artist Adam Ritchie, photographer and film maker Jonathan Barnett, Director of the Portobello Film Festival They talk about how the Gate Picturehouse chain and potential for screening independent shorts, the Barbara Stone Archive that has just been deposited at Kings College London and the vibrancy of community activism and counter-culture in North Kensington. Many thanks to Jonathan Barnett and Lee Ellwood for facilitating this event. Jordan Stone for providing background research. Narrated by Jackie Kearns with performances by Richard Seedhouse, Claire Finn and Harvey Steven. Costumes by Adriana Solari. Filming and sound recording by Harry Green.

Photo above, from left to right:

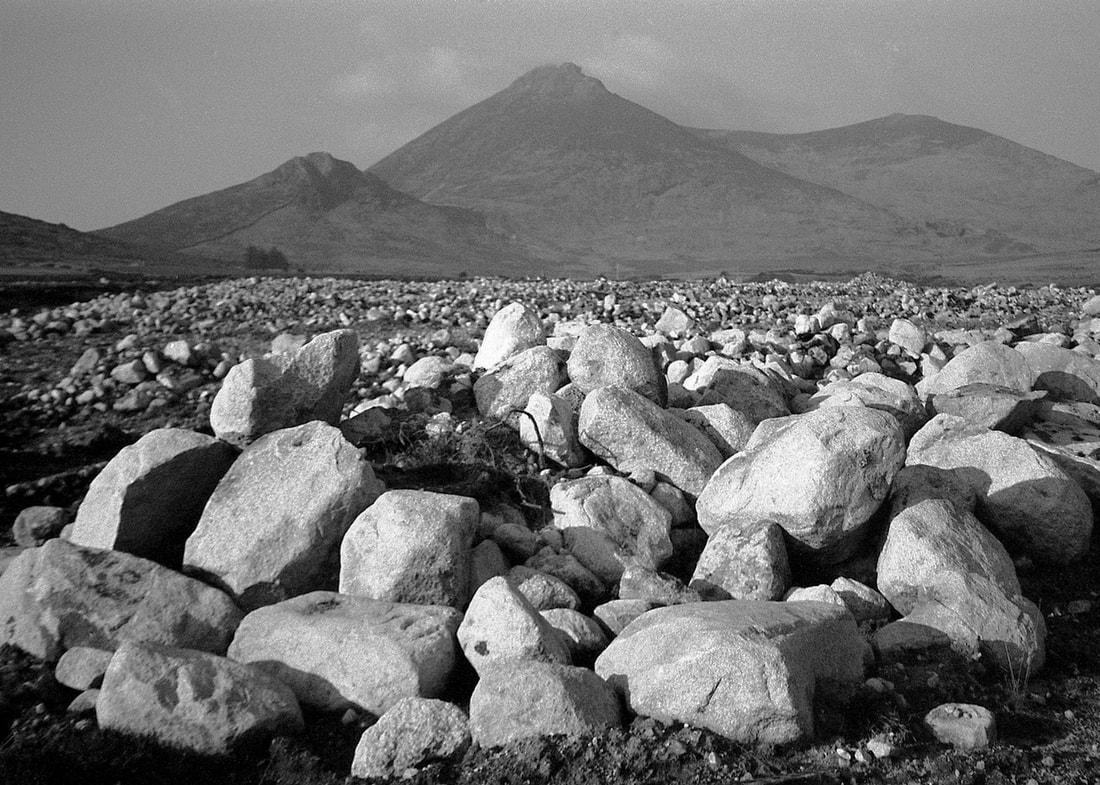

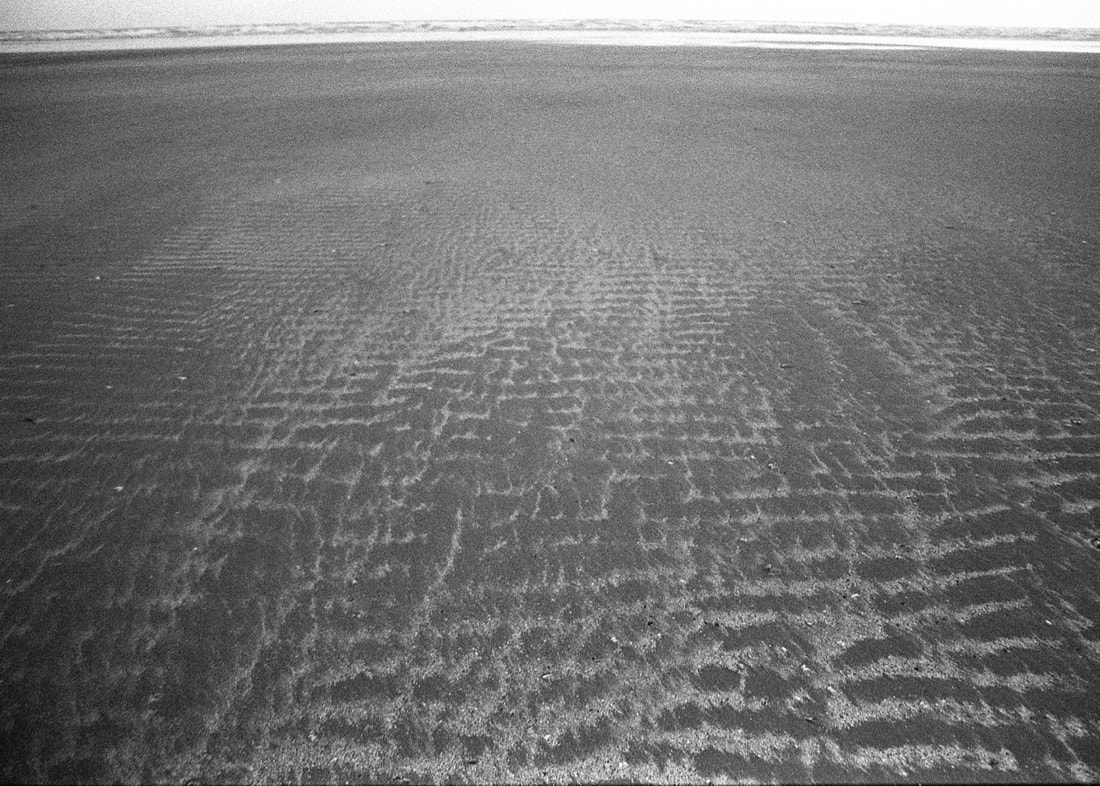

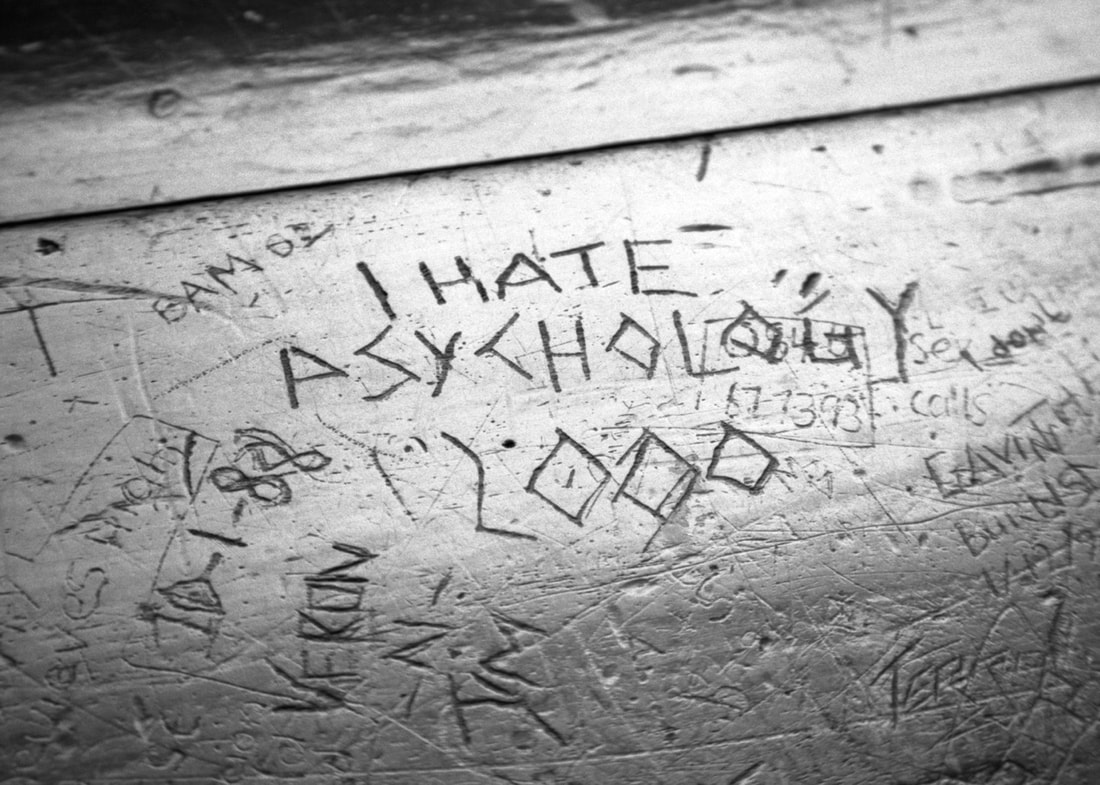

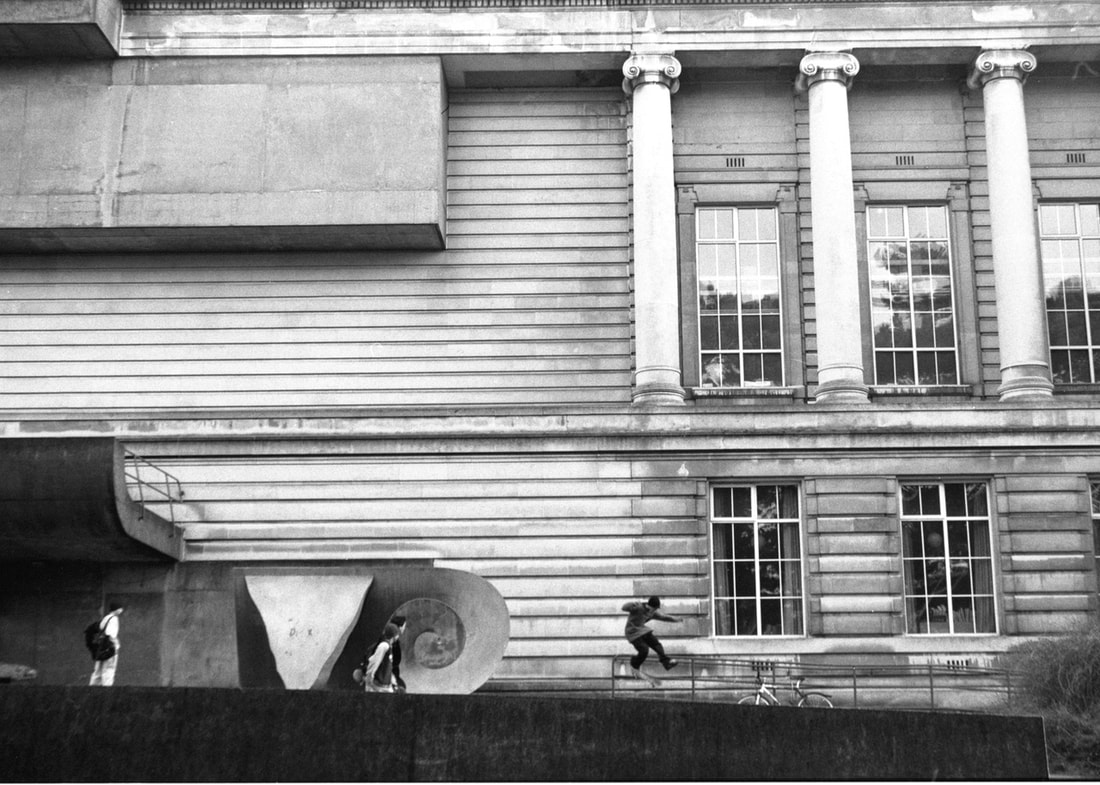

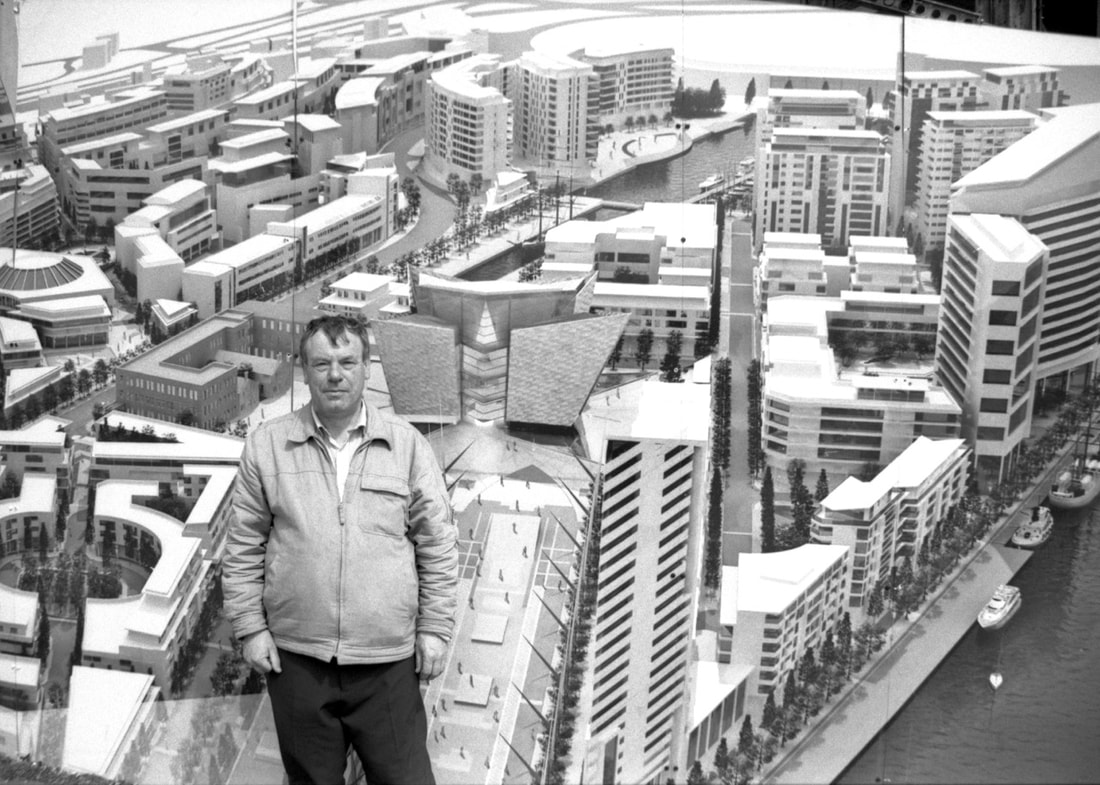

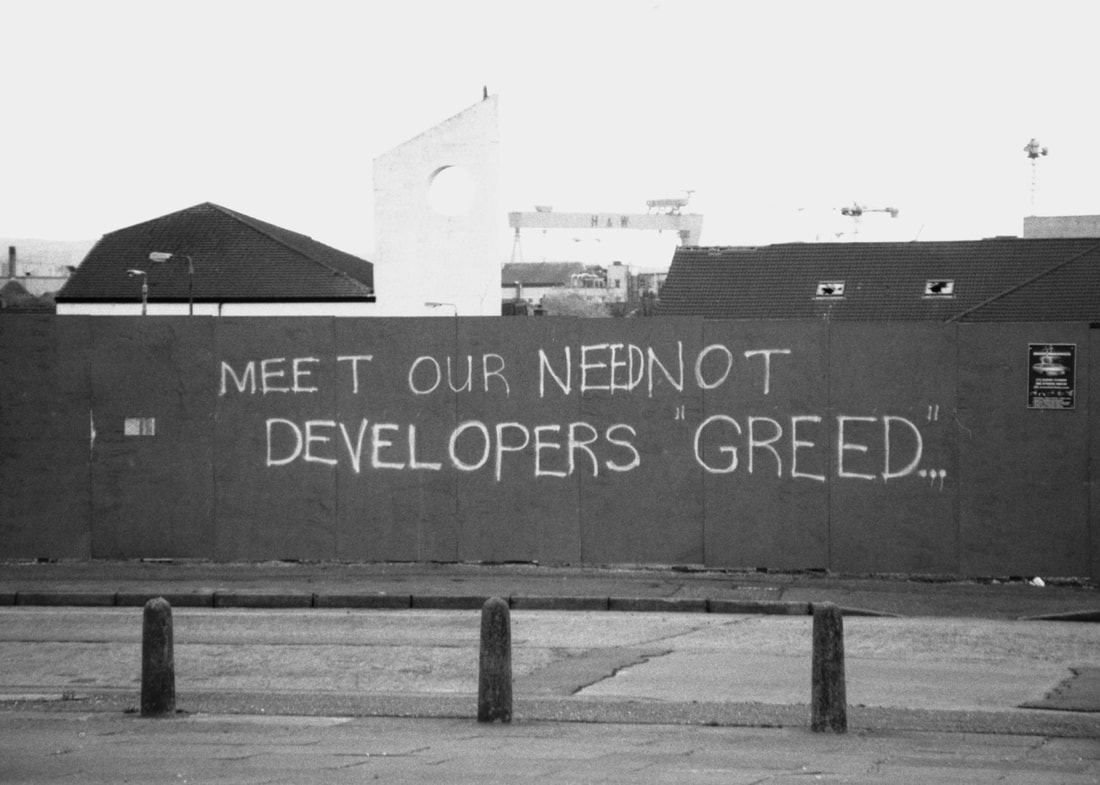

Horace Sedger, director of Electric Palaces Ltd that opened the cinema at 87 Notting Hill Gate, in 1911. Barbara Stone, manager of Cinegate and Gate Cinema that opened in 1974. Stewart Wallace, gardener at Lancaster West estate who stars in The Strawberries Are For The Future (2019). Come, my dear referendum Go deadly cat > apps < bleed the VHS signal The night I buried my passport (in 1973) A suitcase for the deal Euro sting in the Scorpion's Tail The torture of Article 50 What have you done to Therese's voice? Whiplash for the body politic The killer rubber dub (out of sync) Brexit - My Giallo 10.5 x 15cm, oil pastels and pencil 2019 (going on 1973) This is an abandoned film that was being shot from the Mourne Mountains to the city streets of Belfast from 2003-2008. There was a narrative thread: A student who came from a farming background becomes a political activist and drug dealer. Under a shroud of mystery, they are reported missing. One year on, we pick up the narrative, as a family member, ex-bobby, recreates their last known movements. Murder, suicide or a staged death to start a new life? Audio from a lecture room: "It has been argued that there is no fundamental difference between fiction and history. What we know about Julius Caesar - Et tu, Brute? or "καὶ σὺ, τέκνον" Is derived from a long catalogue of narrative forms; Storytelling about him that has been rewritten by each generation. We know as much about Caesar as we know about Molly Bloom. Something is real but not necessarily what the historians are telling us. Your man, Derrida, said: "il n'y a pas de hors-texte." There is nothing outside the text and we should add mobile texting. All our lives are made up of texts that also function as personal anecdotes. This is not necessarily true, as obviously, somethings are true; That ghoulish head skating past the window right now, The underclass who face poverty and premature death Or the student loan and its implications for your survival; All these represent aspects of the real world.” Images are now presented as open-ended, encouraging the viewer to replay and reconfigure, making up their own story, characters or mood in a variation of a black and white silent film.

You are on a mission, but beware - there is no past and there is no future.

Baudelaire did not fly or Rimbaud die and Lemy Caution is missing in action.

Rendezvous: "Brown tie?"

Password: "And braces!" I am waiting here for the French agent with feathered hat.

The phone does not ring.

Still waiting. I am distracted by the kamikaze dive of a demented fly. In one hand, a book of poetry by Anna de Noailles. The other to mouth, sipping champagne out of a cracked glass. I spy a refracted card being delivered under the door. This facet a clue? That one a trap?

At the Institute I am ushered into a meeting room.

The silhouetted outline of a man is framed by a monstrous clock. It has no second or minute hands. The machine activates and my brain quivers.

I come round on the floor in a darkened cell with a folder in my hand.

I crave to read the contents, but.... I... wake.

I... wake on a bench outside the Louvre which is turning inside out.

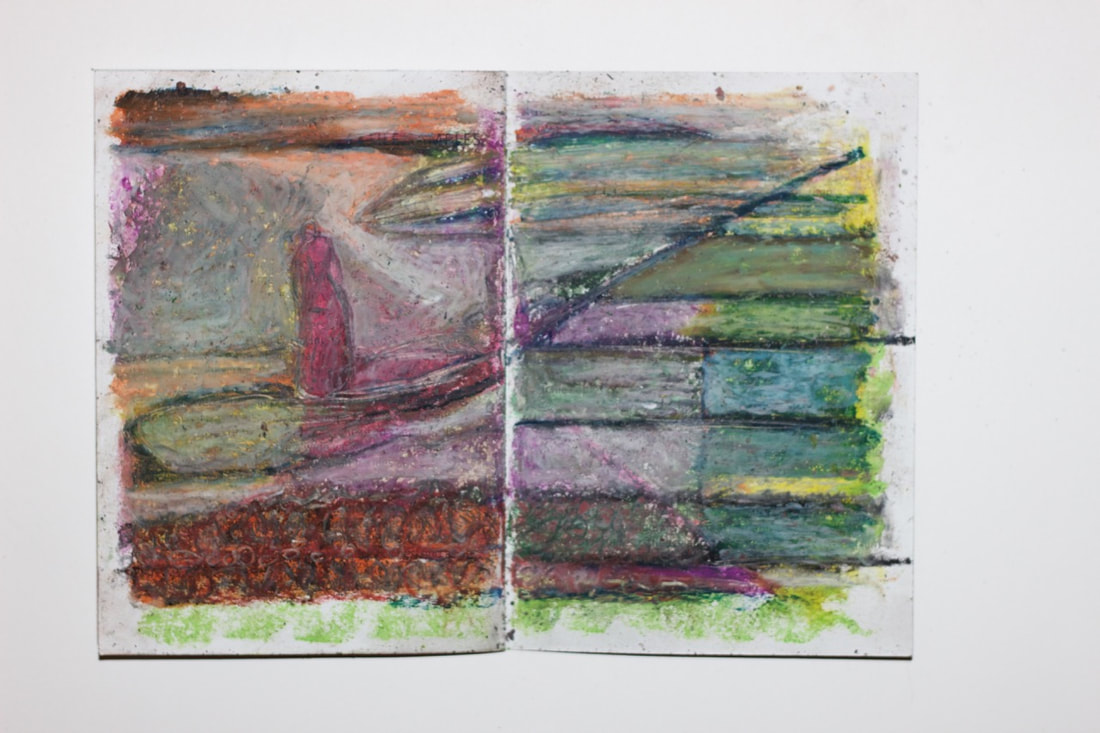

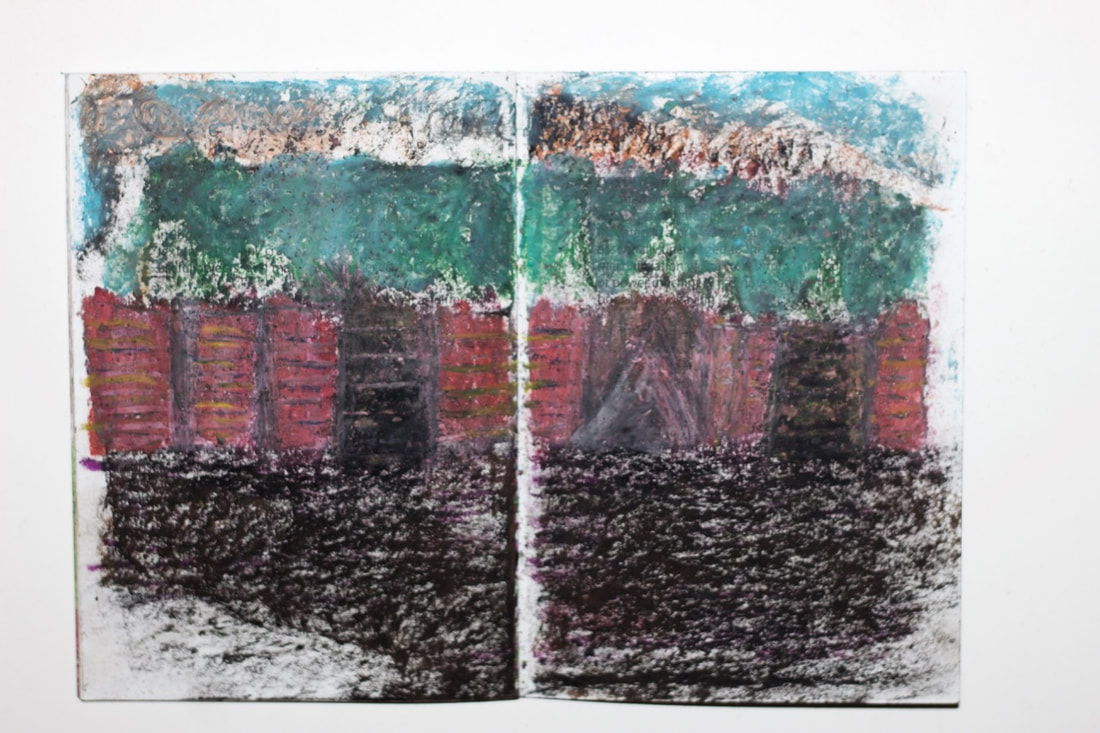

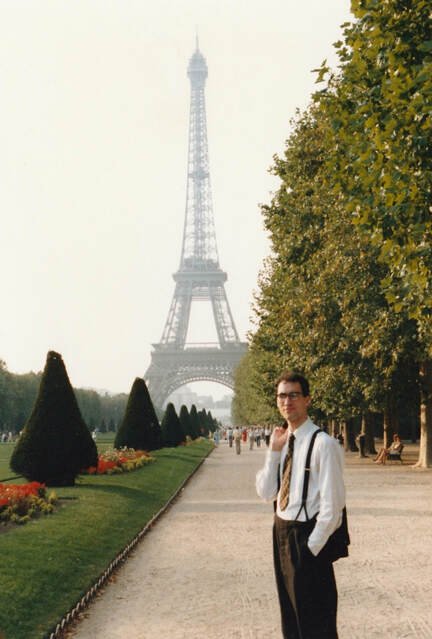

My memory has been semi-erased. Was I.... a.... European son? Madeleine? Painting 1: The Poet's Elixir After Baudelaire Or in other delirious words: "Pretty witty twoon. Swoony noon loon." Acrylics and collage. 10 x 14" 1991 Photo: Down and out in Paris Summer, 1987 Business card Hotel de Champagne et de Mulhouse, 1987 Leaflet Advance Computer Institute, Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre, 1987 Folder 1986: Visnews International news agency that broadcast the first daily satellite news service. Drawing 1: Louvre, Outside In Oil pastel and pencil, 22 x 17" 1996 Drawing 2: Louvre, Inside Out Oil pastel and pencil, 21.5 x 19" 1996 Filmic sub-text: Cléo de 5 à 7 Directed by Agnes Varda, 1962 and starring Corinne Marchand Alphaville: une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution Directed by Jean Luc-Godard, 1965 and starring Eddie Constantine A blog entry inspired by seeing these films after an absence of 30 years; akin to waking from a dream. I will overcome e-motion and travel sickness in search of past-tense, future-flex. A year begins with John Whelan (pictured above) and myself sketching out a project plan and ends with an accumulation of Chaplin books: most of the pages well thumbed and words digested; some semblance of meaning extracted for artful purposes. But for a long period of time, I subscribed to the view that Buster Keaton out-classed Charlie. There is still a snobbish tendency to belittle the "Little Fellow," regarding his playful anarchy as a mere slap and dash; although, fair to say, this primal quality holds true to the early Keystone films. Funding permitting, a major arts project in 2019 will redress this balance and more. John and I want to commission ten artists, all working in different media, to explore the contemporary relevance of Chaplin's life, politics and films; rooting this in the community context of Lambeth and Southwark where he was born and bred. Imagine a month long festival of Chaplin-inspired art! We want to build on the Arts Council funded, The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle (2017), where we imagined Chaplin meeting Michael Caine outside the Coronet Theatre in the Elephant and Castle. Reading The Tramp's Odyssey, I was particularly moved by an interview Chaplin gave to a journalist from the New York Times in 1920. Chaplin was by this stage a global film star. His iconic image had evolved from the Satyric drunk into a rounded character who could command the high notes of comedy and the lows of pathos. The Kid in all its majesty was around the corner, arguably his first masterpiece. Chaplin had also become mega-wealthy and powerful, calling all the creative shots in his own studio. But only a few years before he was a struggling performer on the stage, having endured the hardships of childhood in slum-torn Walworth and Kennington. Chaplin's parents were both music hall performers: his alcoholic father had abandoned the domestic life; his mother would suffer from psychosis. With no parents to look after Charlie and his brother Sydney, they both spent time in the workhouse. In the interview, Chaplin recounts Christmas as a seven year old at the Central London District School for Paupers. Presents were being lined up on a table for the young inmates: tin watches, bags of candy, picture books. Chaplin had his eye on one particular object, a "big fat red apple". He had never seen such a beautiful fruit before and perhaps was motivated by a hunger that the institutionalised food could not meat/meet. When he was approaching the front of the queue, an elder pushed him out of the line and took him back to his room. Chaplin was haunted by these brutal words: "No Christmas present for you this year, Charlie - you keep the other boys awake by telling pirate stories." As it's the season of goodwill, let us rewrite history and surround Chaplin with apples and exotic fruits galore. The photo above shows the seven-year-old Chaplin (middle centre, leaning slightly) at the Central London District School for paupers, 1897. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons. What were those pirate stories Chaplin told his peers and which got up the snooty noses of the authorities? We can visualise him acting out cut-throat characters, obsessed by trinkets of gold. Perhaps this play had an element of the outsider, the Tramp that was to be. I am also paying my own black and white homage to Chaplin with the following series of photos. Fade in to the Church on the High Street, Willesden, the year of the Second Millennium. A cleric is fighting a losing battle to the world outside but maintains his sense of humour. The Tramp wanders into shot with a new bowler hat, baggy trousers and overripe boots that was bequeathed to him down at the Clothes Bank. He is seated on the wall oblivious to the sign above his head. He tries to make eye and smile contact with each passer by. They avoid him like the plague. The Tramp suddenly screams in silence. There is an attack in his jacket breast pocket. A circus of fleas from the previous owner of the suit? No! He pulls out a....... The title card reveals it is merely the ringtone of a new fangled mobile phone. Welcome to the year of Chaplin, 2019. An original screenplay that has been made into a commercially successful film, will generate merchandise, possibly a book. Hard Earth has the distinction of being a collaborative script made by actors and visual artist. It is based on the premise of a poetic mum (Jill) who is undergoing an end of life experience. Her son (Toby) and his partner (Mandy), whose relationship is in turmoil, are on the receiving end of her enigmatic reflections. Aged tree. You cool your feet in the calming stream. No human eye sees how your roots Reach through the hard earth To tend and nurture your fellow trees. Aged tree. Cold, still stream. Hard, hard......hard earth. This is the artist's book that was made during the scripting process: Page 1: Mandy and Toby trapped in a car. Page 2-3: Where is Jill? Page 4-5: Jill looks at the trees and Toby his office. Page 6: Fragments of a poem drift down stream from the hill.

One family. Three divided people. "What am I to be?"

A short drama starring Tiberius Chis, Jackie Kearns and Michelle Strutt. Script by Jackie Kearns, Tiberius Chis, Michelle Strutt and Constantine Gras. Poetry by Jackie Kearns and sung by Sam Chaplin. A Gras Art production. Premiere screening at the Portobello Film Festival Nominated for Best Drama Film. As I prepare to film a short drama film called Hard Earth, I return back to a previous rare outing in this genre. I can now register the achievement of that 2011 film and see a future teeming with collaborative potential. It's nice to work outside the experimental art genre that informs the bulk of my film output; although my last film, which was also my first feature, a documentary about Lancaster West estate, has been withdraw from circulation after the tragic fire at Grenfell. It was 2010 and I met the actress Gwendolyn White on an arts project called Water Works. We became good friends and decided to make a film based on a story she told me about her mother. I also set myself a challenge to tell a story in 1 minute. Almost haiku in tone, we have no dialogue or exposition in this documentary drama. The hand powering of a Singer sowing machine unlocks a matriarchal memory of love and a sense of cultural identity born out of an old slave song that became a gospel classic. Screened at the In Short Festival, Lexi Cinema, Portobello Film Festival and Walthamstow Short Film Festival, 2011. Talk? Perhaps the actors, Michelle Strutt and Tiberius Chis, thought the same thing when invited to attend the second workshop for a film project that is being created from scratch. But I had the left of centre idea of getting them to interact with the cultural happenings that took place on 24 March 2018 during the West London Gallery Bus Tour and improvise characters, moods and potential plot developments. I also wanted to test the actors in a live situation and observe their on-screen chemistry; they both responded fabulously in the chaotic circumstances. I had worked with both actors before in The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle which was a play, film and exhibition project. Michelle had played one of the four narrators in the play and Tiberius had several roles including a memorable portrayal of Charles Chaplin. A similar exercise had already been undertaken at Canada Water with the other actress in the project, Jackie Kearns. Her creative writing had inspired one of the themes of the film: “Aged tree, you cool your feet in the calming stream. No human eye sees how your roots reach through the hard earth To tend and nurture your fellow trees. Aged tree, cool, calming stream. Hard earth.” These episodic and fragmentary elements of a dramatic triangular relationship should be viewed as marginalia for a forthcoming film. I Thought You Were Going To Talk is an unorthodox trailer for what might turn out to be a completely different but related film. Many thanks to Rob Birch, Piers Thompson, Fifi la Mer, Olly Wilby and Gosia Lapsa-Malawska for their support during the Gallery Bus Tour. The tour was organised by The Galleries Association established by Damian Rayne of the Muse Gallery. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed