|

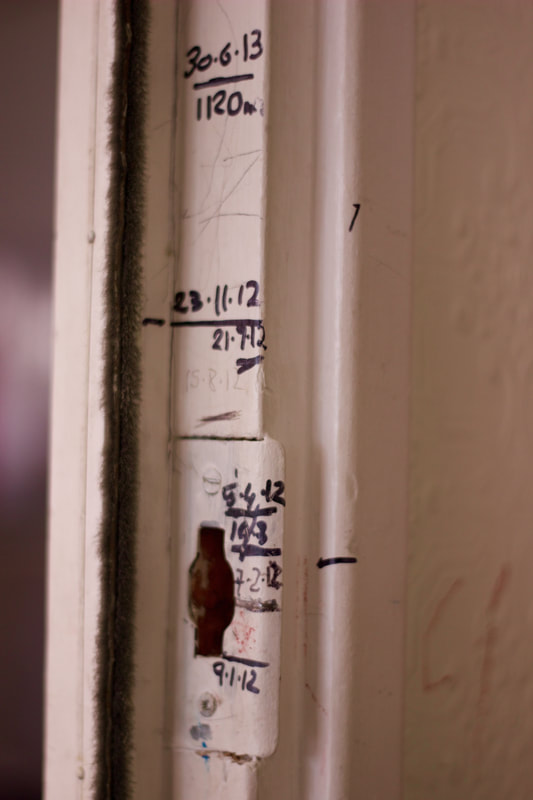

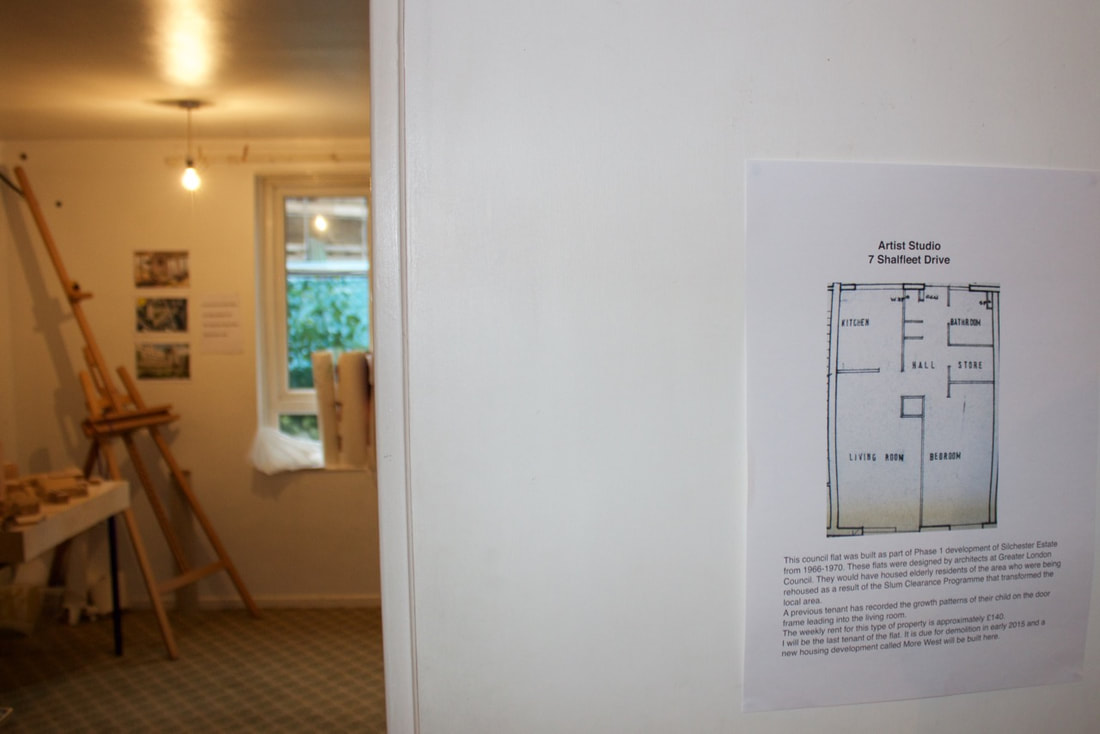

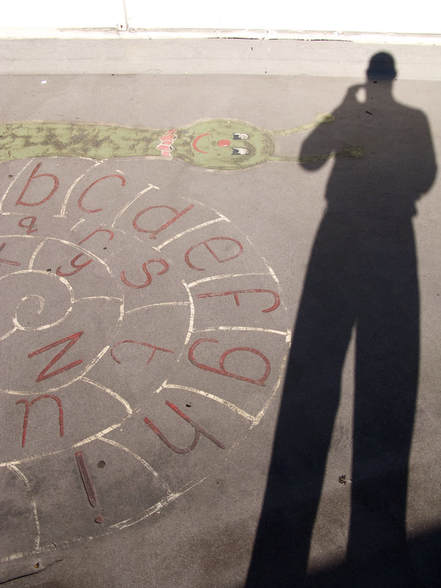

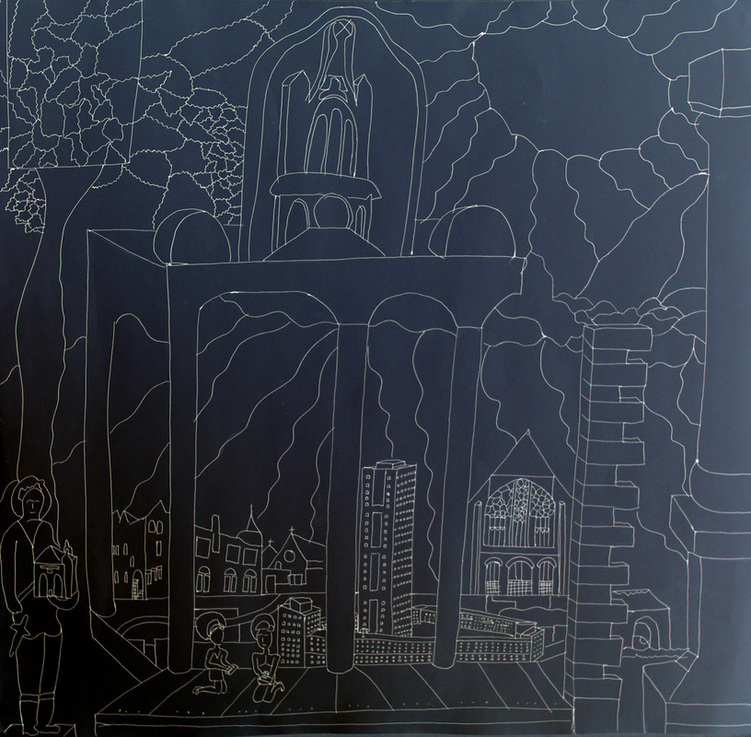

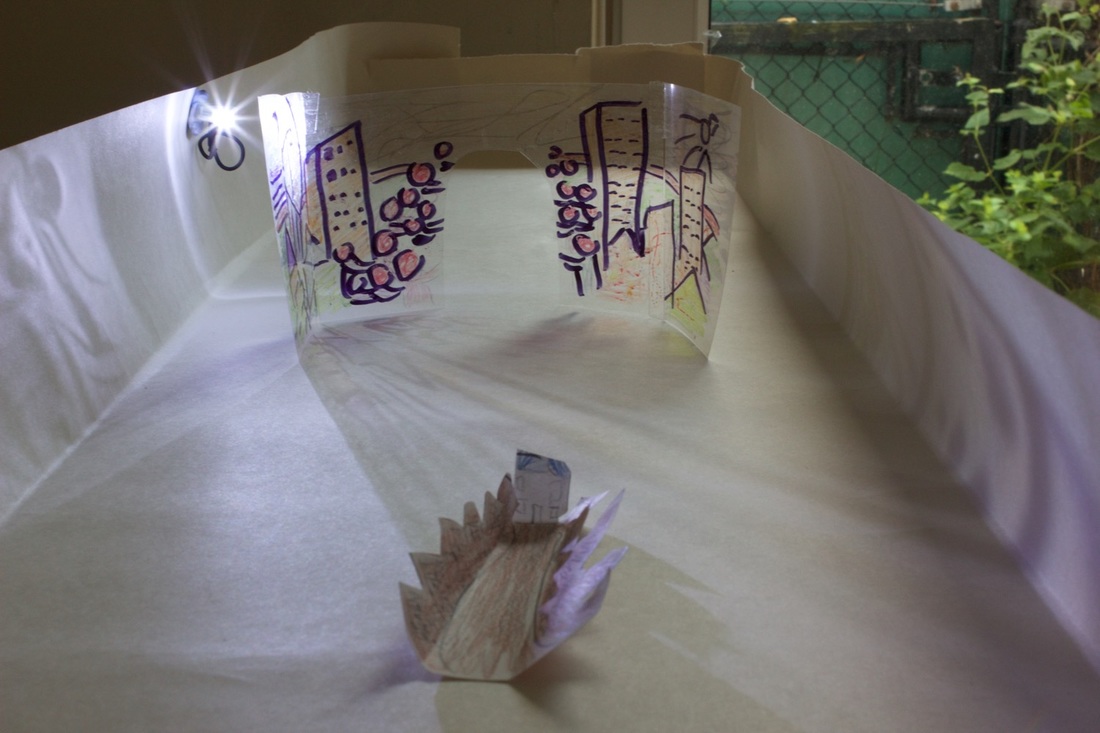

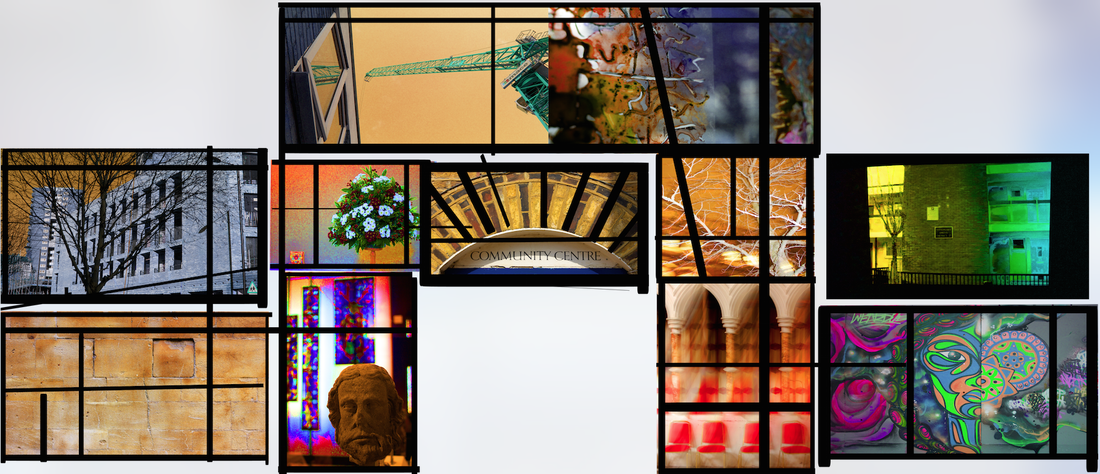

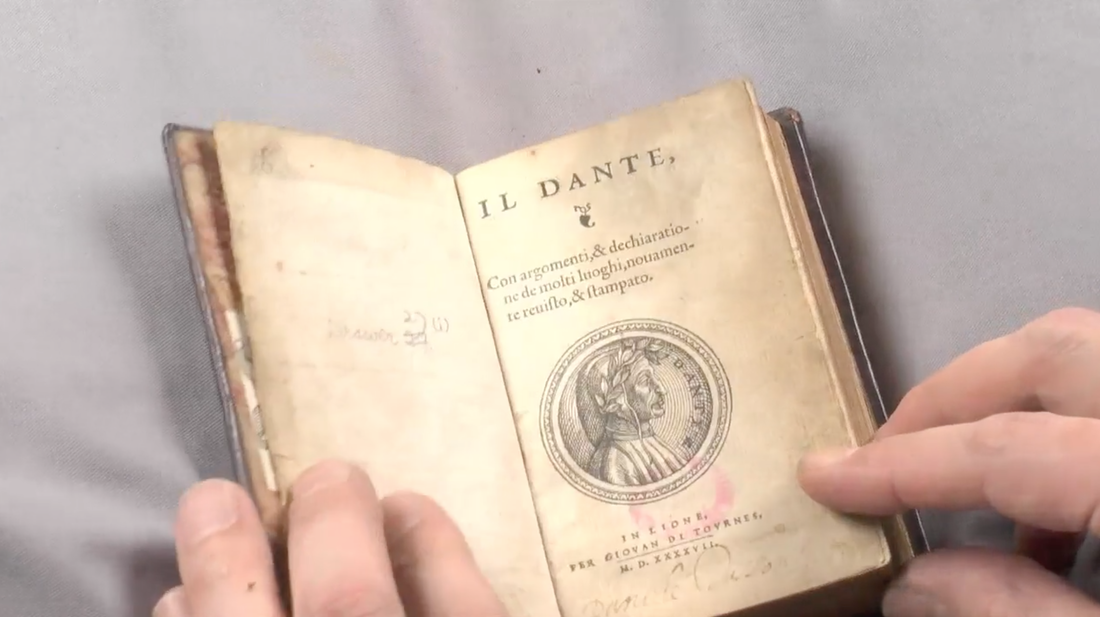

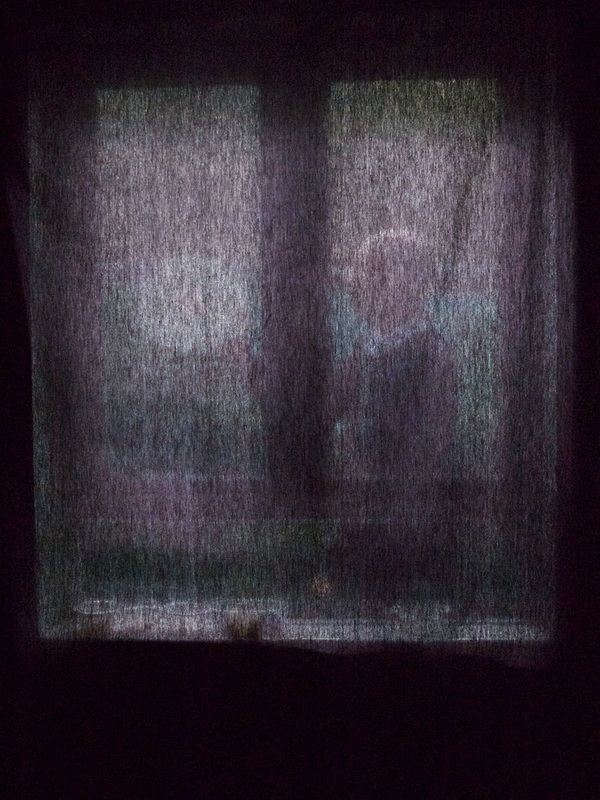

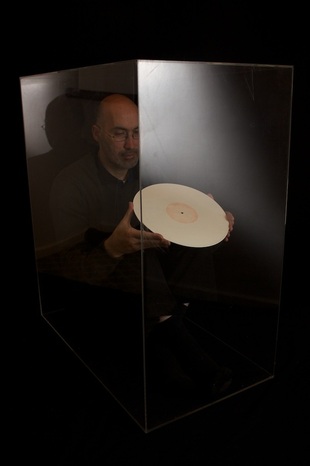

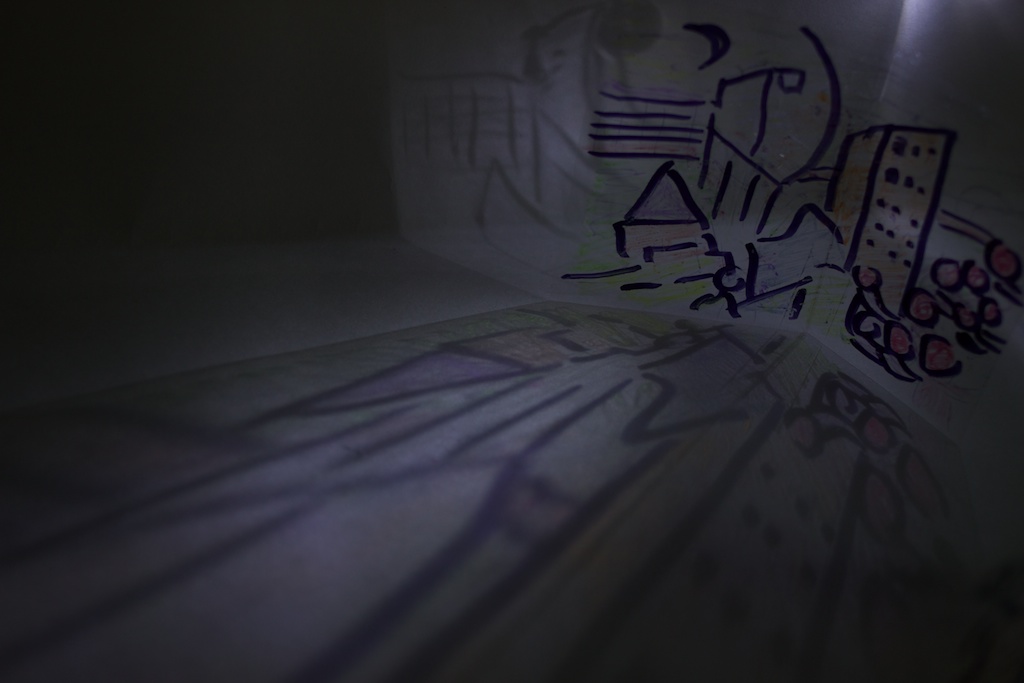

Reflection from artist studio as More West is being built The chronicle of a child's growth recorded on a door frame Photos taken at 7 Shalfleet Drive, 2014 Can a building have a soul? If so, how might one measure this on a scale of soul from 1-10? One? Nah! This is just a plain pile of functional brickwork or unloved concrete. To give it a Presidential seal of approval, "a shit hole!" Five? Maybe given its provenance and state of use, there is a connection being forged between property and person(s). Perhaps a bog standard church and appreciative congregation might fit this bill. Ten? Now this might be hard to put into words. Some otherworldly sensory experience of an English castle made in heaven. A building that has survived carbuncular judgment and phases of regeneration. A cave you have carved with your own hands or flat packed assembled. Excuse these digressions, as this is completely uncharted territory for this author and a subject matter reserved for the confines of a philosophical department in a city of dreaming spires. Let us return to North Kensington terra firma. This blog is about 7 buildings, most within several hundred yards of each other: one was built as a film set and several have long since been demolished. They are St. Francis of Assisi church (c1860), 1-2 Whitchurch Road (1863), 2 Silchester Terrace (?-1960s), 7 Shalfleet Drive (late 1960s-2015), Latymer Nursery (late 1960s-2013), Grenfell Tower (1974) and More West (2016). The question I ask is do these buildings, historic or contemporary, have a recognisable soul beyond their outer facade? I have worked as an artist in three of them, one as a rented studio flat. While looking at spiritual qualities, I want to relate this to how I have used them in my art, the intersection of aesthetics and politics. To complicate matters, I have to declare from the outset that I'm not mystically inclined or believe in angels. However there is definitely more in heaven and hell than can be dreamt of in my atheistic philosophy. 1-2 Whitchurch Road House built for stain glass artist Nathaniel Westlake in 1863 Currently a St Mungo's house for homeless people St Francis of Assisi church Side chapel roof designed by John Francis Bentley, C1860's House for Nathaniel Westlake displayed at the V&A Museum, 2015 Acetate sheets, 3x3 metres Let us return back to that proposition. It is a line from a film, completely unscripted and conjured forth from the consciousness of the gardener at Lancaster West estate, Stewart Wallace. When I asked him how he knew this building had a soul, there was an even better quip: "I wouldn't be an angel otherwise.” The soulful building in question was 1-2 Whitchurch Road. Stewart had been living next to it for decades and said if he won the lottery, he would buy it and lord the manor. The building was the home of Nathaniel Westlake and designed by his close friend, the architect, John Francis Bentley of Westminster Cathedral fame. So we have soul pedigree here. During the 1860s they were both converts to Catholicism and working on St Francis of Assissi church which was a stones throw away from this house. This was a part of London noted for its piggeries (pig farmers) and potteries (brick works) and undergoing urbanisation with the coming of the railway and the growth of an Irish community. Westlake did not stay long in his dream house and we can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. Amazingly this grand looking house, that is now listed, was once a squat and is still used to house homeless people. The building was a key location in my film, Vision of Paradise (2015). This was a meditation on housing and community using Dante's concept of heaven, hell and purgatory. In 1863 Westlake was working on his stain glass design, The Vision of Beatrice, to illustrate a scene from this story while living in the house on Whitchurch Road. This panel was collected by the V&A Museum. As an additional homage, I made an installation called House of Nathaniel Westlake, comprised of 30xA2 acetate sheets incorporating images of North Kensington buildings. Soul value: 8/10 for its origins and continued charitable use when this type of property would be snapped up by oligarchs and venture capitalists; although shame on them as they would not want to live cheek by jowl next to an estate! As mentioned, Bentley and Westlake put their heart and soul into St Francis of Assisi church. This is a small church with connected buildings on a tight plot of land, but the overall design and interiors sing of the unique talent of its guiding architect and artist. This is self-evidently a soulful building with a wonderful acoustic quality. For the remastered film soundtrack to This-That, I recorded two singers here performing a duet called Duo Seraphim. 9/10. Staff from the V&A Museum help me prepare for a community artist event 21/08/14 7 Shalfleet Drive, W10 6UF Mayor of RBKC meets local residents and architect of More West, Joanna Sutherland Demolition of Shalfleet Drive, 12/02/15 During 2015, I was the V&A Museum community artist in residence based at Silchester Estate. The first phase of regeneration was occurring in the area with the building of More West. I was embedded here with a studio flat at 7 Shalfleet Drive. This was part of a lower and upper deck housing block with 3 room flats that must have been designed for a pensioner or a couple, certainly not a family. So did this flat at the end of its social life have a soul? I would rate it 7 for its cosy uniformity of space, perfect for an artist who tried his best to give it back to the community with a series of bespoke art events that included film screenings and drawing/music happenings. Centre stage in the living room of that flat was a simple map which had photos of all the listed buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The addition of Silchester Estate on this map was the radical touch that only the locals noted. This map was a popular attraction to the visitors, including the then Mayor who came to an event called I Want To Live, Draw Me A House. Before she arrived, the police dropped by to inspect my premises. It seemed they had valued the spirit of the location in terms of a negative. It was an unknown precedent for Mayors to visit council flats on estates in North Kensington, even ones about to be regenerated. I was told this was a first. Film projection of Home about the last house demolished for the building of the Westway and Silchester Estate. It was screened at Latymer Project Space, formerly a nursery on Silchester Estate and soon to become More West. Photo by Emily Ballard, 2012. We move onto a house that now only survives as an archive photo. It was taken by the actress Mary Miller in December 1967. She wrote an accompanying letter that read: “I remember taking this picture of a house and a tree amongst the rubble and desolation of the early stages of the motorway from Bramley Road, looking west. It looked so forlorn and I admired the tenacity of the householder. i seem to recall it was an elderly man. There was something about him in the local paper of the time (I can’t recall which paper exactly). But a few weeks later he had succumbed to the pressure and the house was destroyed - also the tree. I think it all happened round about the time they blew up Maxilla Gardens for filming with Marcello Mastroianni.” This had all the ingredients to inspire the cinematic imagination. A small house that was left standing while those adjoining had been demolished. That solitary man with raincoat and hat standing outside. The corrugated sheeting. Even Mary’s reference to Leo The Last that was being filmed near by. I simply had to tell the story of this photograph. I presented this as a short film pitch to Latymer Projects. They accepted and I made Home for their inaugural exhibition. I acted the role of that homeowner from the photo. You don’t see me/him clearly as we move nervously around a house and twitch at net curtains waiting for the developers to serve us an eviction notice. At the end of the film, there is a panoramic shot of a net curtain house constructed on the Westway tennis courts, on a spot that marked the real life location of this lost house. Given all these resonances, I would have to evaluate this lost house in the photograph, as an 8 for its elegiac soul. Set design from film, Home (2012) Cinematography by Natalie Marr Film still from Leo The Last (1970) with Glenna Forster-Jones (left) Filmed in North Kensington and on Testerton Road before its redevelopment into Lancaster West Image kindly reproduced by Park Circus Limited Leo The Last is a quirky, enigmatic and powerful film that dramatically deals with race and social conflict. It was made by John Boorman in the late 1960s. It is a film of its time with hippie experimentation. Yet also profoundly prescient in that it tapped into the zeitgeist of the area. It remains a touchstone for thinking through art and redevelopment; it inspired me, as I feel certain it will continue to do so for other artists. The film makers were given unique access to the streets of North Kensington just prior to its slum clearance and they created a false house on Testerton Road. This had a white classic stucco facade and contrasted with the rest of the derelict houses which were painted black. This is a colour film with an impressive monochrome palette. Leo is the last in the aristocratic line and for the opening sections of the film peers out of his house with a telescope onto the world of his opressed black neighbours. He becomes radicalised by observing their plight, especially when he discovers he is their exploitative landlord. In true 60s fashion he decides to stage a revolution with destructive consequences. I felt a great affinity with Leo. As an artist, I was using my camera and drawings to reflect on changes to my social environment and in the process was being radicalised. I was getting a deep understanding on the cultural richness of life on these estates. Yes. There are social challenges, but these were not the sink estates as portrayed by politicians and councillors intent on running them down and forcing through regeneration schemes. As part of my community engagement, I got hold of a rare 35mm print as the film was not available in this country on DVD . I screened this for residents at the Gate Cinema (which is in the Notting Hill and not the Dale part of the borough). After watching the film residents from the estate joined me down at the V&A to create clay houses in response to the film. I was able to use this as part of an installation display at the museum. I have to give this film-set-building a 10 on the soulful scale. It has mythic and poetic qualities. It was built in order to be destroyed. Many local residents and the architects of Lancaster West Estate came to watch the impressive finale as the house explodes in flames. What did they think and feel watching film makers turn their former homes into a film set prior to its demolition for the building of Lancaster West and Grenfell tower? The soul of their buildings disappearing at a rate of 24 frames a second and then projected at cinemas in the following year to a largely unappreciative audience and box office. Latymer Nursery converted into Latymer Projects 154 Freston Road, 2012 (Bottom photo by Sandra Crisp) I also developed a strong connection with a former nursery on Freston Road that was built as part of Silchester Estate. This was handed over to Acava Studios and Latymer Projects as a temporary space for local artists prior to its redevelopment into More West. I made a film about the space and the 5 artists based here in its last days. I arranged for a local milk man to deliver one final crate. At 6am, in eerie darkness, I filmed him delivering his jinggling bottles. Then later on I improvised a sequence with other artists in which we walked around the nursery using these bottles as musical instruments and creating a trail of fragmentary glass. The nursery for children and artists had a special atmosphere. We were at home in its play spaces and rooms flooded by natural light. 8/10. More West was built on the site of my artists studio and the Nursery. It was an indicator of how the council wanted to replace social housing in the area by building around the high rise blocks. This must have also been part of the thinking behind the £10 million investment in Grenfell tower that was to follow. More West was Peabody housing for the 21st century: 112 flats with mixed social and market rent; £500,000 for a three bed flat and million pound penthouse pad on top, perhaps with a telescope trained down on its poor relations. Leo The Last meets J. G. Ballard’s High Rise. I tried to avoid my flat being used as a showroom by the developers and council. The architects model of the new housing block was on display next to a poster of the film Leo The Last. I would film spiders constructing their silky webs as builders climbed up and operated cranes. I got to know my immediate neighbours on the road who were waiting to move into More West. Some took this in a positive fashion, others clung to the memories of their former lives. The building was designed by Haworth Tomkins, complete with roof top sculpture that evokes Frestonia and has won many architectural awards. I have a soft spot for this building, but acknowledge it has yet to plant roots and be integrated with the high rise. 7/10. It is a building in need of love. Shalfleet Drive residents hand over keys to the developers, 18/01/15 More West (with crane in the centre) being built around Frinstead House on Silchester Estate View from the 17th floor of Grenfell Tower, 12/09/15 Building work collage: Frinstead, Markland, Dixon, Whitstable and Grenfell tower, 28/06/15 I wanted to conclude this blog by writing in detail about Grenfell Tower where I worked for one year four months. I was commissioned to made a film about the regenerated tower block and produce art for its new community room. I developed close friendships with residents. I don’t know how to evaluate the spirit of this building. It still pains me to talk about it in the past tense. As a postscript, let me branch out and offer a few comparative thoughts about the 1958 Notting Hill race riots and those tragic events at Grenfell Tower in 2017. Both shone a media spotlight on this area around Latimer Road station and exposed the deficiencies of society and council services. The chronic state of housing must have been a factor causing friction between white residents and the recently settled Afro-Caribbean community. Sociological studies took place into the root causes and how society could improve itself. In the immediate aftermath of both events, all manner of groups and social activists consolidated networks in the area to counter the lack of strategic guidance from the authorities. The Notting Hill carnival was one of the unexpected outcomes of the riot. What will follow the Grenfell Fire? I fear no positive outcomes in the short term. As of writing, the civil and criminal prosecutions are yet to unfold. There is great concern that the former will not address deeper underlying social issues and the latter will not result in anything other than corporate fines. It is a testing time to find spiritual qualities in housing and art. Burnt cladding in the garden of Lancaster West estate, 06/01/18

0 Comments

There is a corridor sized gallery at the V&A that I am forever drawn to. Literally, in the sense that I love sketching here. It's the Sacred Silver & Stained Glass collection in room 83. During my tenure as the museum's community artist in residence, I used stained glass to meditate on contemporary housing issues. Nathaniel Westlake's magisterial panel at the V&A, Vision of Beatrice, inspired an installation and artist film. The Westlake stained glass panel was made for a V&A exhibition in 1864 and was possibly conceived in the house that Westlake had built for him in the heart of North Kensington. The house is still standing at 1-2 Whitchurch Road opposite the Lancaster West estate and embodies the complex history of social change from the extremes of Victorian affluence and poverty to modern day regeneration and gentrification. This listed building would be a multi-millionaires paradise but has been converted into six bedrooms by St Mungo's and is a hostel for those needing support into housing and work. The house was situated just across the road from my artist studio which itself was a former council flat about to be redeveloped into More West. During my residency, I recorded an interview with Terry Bloxham who is a ceramic and glass specialist at the V&A with responsibility for the stained glass collection. I wanted to understand more about the context in which Westlake had made his stained glass panel and Terry quite rightly took me back in time. I was surprised by how the past would resonate so strongly with the way we live today: the forging of nation states; how religion can violently divide and spiritually unite; and the evolving technological and economic context to the making of art. Here is an edited transcript of our coversation: Terry Bloxham: Why Westlake? Why that panel? Constantine Gras: Why that panel? I didn’t know anything about it until I started my V&A Community Artist residency. I’m based in a studio in North Kensington that is part of an estate, the Silchester Estate. It’s part of a new housing development taking place on the estate. In the run up to my residency, I cycled around the borough, looked at listed buildings and I came across a house, just across the road from where my studio is. It’s the house that was built for Nathaniel Westlake. TB: Oh. Who be he? CG: It’s a bit of a juxtaposition from the estates. You suddenly see this listed building that was built in 1863. It was built by his friend and architect, John Francis Bentley, who later went on to design Westminster Cathedral. And they were both converts to Catholicism and collaborated on St Francis of Assisi church on Pottery Lane in North Kensington. But I was interested in this grand looking house near an estate and that's now run as a sort of hostel. It’s had a bit of a checkered history as this area of North Kensington has. Poverty and slums. Now property that is valued in the millions. TB: Where is North Kensington? CG: This part is opposite Latimer Road tube station. TB: I think I know. Basically Notting Hill west. CG: That’s right. TB: I know that neighbourhood. There’s a great reggae shop. Hopefully it’s still there. CG: So that’s how I came across Westlake. As an artist with a studio in the same area, albeit in a different century, I’m very interested in predecessors and making connections with them. And to discover that the V&A museum has a work of art that has a connection to the very streets in which I'm working. I’m also interested in a film that was also made in the local area and this is called Leo The Last. It was made in 1969 by John Boorman on the site of Lancaster West estate just prior to it being built. It’s about an aristocratic person who moves into the area and he gets radicalised by his interaction with the West Indian community. Some memorable imagery in the film involves looking through a telescope and also patterned glass in a pub that distorts the point of view. I suppose at one level, I wanted to explore or create a connection between film making and stained glass. In the sense of camera lenses and glass transmitting light and how they might be used for perception and analysing or documenting the world around you. Using fragments or a diverse range of media that can be pieced together to make a whole new work of art. And one not necessarily made just by the artist, but involving collaboration. Also I feel a little like that aristocratic character in the film. The artist as an outsider who comes into an area and interacts with the community and how this might radicalise either them or the community or not as the case may be. That is the type of thing I’m wanting to do in my community focused project work. I’m hoping to create a Westlake House at the V&A Museum, in addition to making an artist's film. TB: Brilliant. CG: Perhaps you can help me shed some light on Westlake and how and why he came to make this wonderful panel. TB: Westlake in the nineteenth century, is, near enough, the culmination of a movement that we now call the Gothic revival. And the Gothic Revival was a reaction against eighteenth century stuff and we are going to be talking about that as we progress through time. This involved a revision in the theological understanding of Christianity and also the furnishings of Christian churches. And all throughout the gothic revival period, whether you are talking about stained glass or metalworking or textiles, all of the things that were used for church furnishings, they kept harping on, we must do it in the medieval manner. And that’s why you’ve got to understand the medieval manner in order to understand Westlake. That’s why we are starting here in the medieval period. We are looking at thirteenth century glass. CG: Was this being commissioned by the church? TB: Yes. it was church law that you had to have some sort of decorative, figurative work in the church, that illustrated the Saint to whom that church was dedicated. All images in churches were meant to be instructive. People always say it’s bibles for the poor. But that’s sort of an insult, because it’s calling them illiterate. And I prefer to look at it, not as an age of illiteracy, but as an age when you didn’t need to read and write. Only a few people did. In the middle ages, TB: So here we are looking at a panel from the mid thirteenth century showing a scene of King Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus or Jermaine. It is telling you a story, an episode from the life of a real king. His name was Childebert. He’s in the middle of the sixth century and was one of the first kings in France. After the collapse of the Roman empire in the West you have all these so called barbarians moving in. You can tell my preferences lie with the so called barbarians. Various tribal groups as they were known: the Goths, the Gauls, the Francs, the Germanys, the Celts. The celts became the Brits. These groups are going to form our nation states. Clovis was one of these Frankish groups and from Frank we get France. This is where Childebert is descended from. In the panel, we have Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus, the first bishop of Paris. He is chastising the King because he had just been on a campaign to conquer the Spanish city of Saragossa. The bishop was upset about this because Saragossa was a christian city. Bishop Jermanus forced Childebert to build the first church in Paris as atonement for his sins and this church was dedicated to St Lawrence. This church was being rebuilt in the thirteenth century in the newish Gothic style and it was rededicated to Jermanus who by then had become a saint. CG: Can you tell me about the designs used in stained glass and the process of making? TB: Medieval decorated windows are composed of small, irregularly shaped pieces of coloured and clear glass. The idea was not to have big square panels of glass which they could make, about A4 sheet size. It was to make a sheet of glass, cut it into irregular shapes and move those shapes around to form a picture. And then those shapes are held together by lead. So it became known as a mosaic-type construction. When you think of a Roman mosaic floor, little pieces of tesserae arranged to make a picture shape. And then they are embedded into cement to form a solid picture. It’s the same thing with mosaic glass. The only painting that you have on it are the details that you can see in the hands and the face, the folds in the clothing. That’s just simple blacky-brown iron-based pigment which is fired onto the surface of the glass. Glass when made is clear. But in its molten state you can add colouring agents to it. Cobalt will make blue. Copper will make green and also red. Manganese will make a purply brown. Depending upon the intensity you can get this nice purply-brown robe or flesh colour. That is know as pot metal because you hold the liquid glass into a pot and add the metallic oxide. So you have clear glass and pot metal glass, cut into small irregularly shaped pieces, put together to make a nice, pretty little picture, all held together in this lead framework. And whatever paint you have was just an iron based pigment onto the surface of the glass to give you your details. That is mosaic glass made in the medieval manner. That is what Westlake is trying to achieve. I have to introduce another element in the manufacturing of medieval glass. Something that was a big technological revolution. I mentioned earlier that properly speaking, it’s not stained glass, it’s decorated glass. And the reason why I say that is because stained means penetration of glass or staining glass. That doesn’t happen until the magic year of about 1300, probably in Normandy. Some bright spark discovered that putting silver into oxide of some form and then firing, what it did was to penetrate the upper levels of the glass and create this lovely lemony yellow to a burnt orange colour. And the reason why that was so revolutionary was it enabled you to have more than one colour on the sheet of glass. We looked at yellow glass and red glass and blue glass and green glass that is known as pot metal glass. That is clear glass that has been coloured. Coloured glass is more expensive than clear glass. Any time you have extra processes it’s going to increase the price. We do have those few surviving documents that give us prices for the middle ages. So we know that glass coloured all the way through was more expensive. Staining it is incredibly cheap to make relative to the older way and once it comes in, it doesn’t disappear. When we get to the Reformation in the sixteenth century, Europe is torn apart by different believers or practitioners of the Christian faith. In the middle ages, remember there is only the church. There is no protestant, no catholic. It is just the church. So you have to put yourself in a time when your world, your faith is being torn apart, is being questioned by people who are very learned and very persuasive. And in some cases also inciters of violent activities and feelings. We tend to blame the whole reformation on him, Martin Luther. He was pretty moderate. You also had people like Calvin and Zinger who were the militant side of the reformation. And there was a lot of destruction and a lot of change. But in Europe today, you will still find this part of Germany is Catholic, but that part is Protestant. But fortunately not fighting each other. England’s story is different and was more violent. Not so much people killing each other, but people destroying anything suggestive of religious imagery. CG: You get a snapshot of those times at the recent iconoclasm exhibition at the Tate. TB: Yes that was a good snapshot. And we also have documents from stain glass makers, petitioning the local leaders of the city, the principalities. Saying you are putting us out of business. We used to make a living making religious windows for churches and it was just no longer allowed. On the continent they started to turn their hands to other iconographic subject matter in stain glass making. TB: What we are looking at now are products of Netherlandish workshops who mastered from the fifteenth century onwards, the art of very fine, but mass and cheap production of glass windows. These are simple pieces of cylinder glass, cut into a circular shape and solely painted. So its clear glass, in silver stain and black pigment. They are cheap. They are incredibly finely painted because this is the age of the printing press. So engravings were made and then they would be printed and they would be used as models for these stained glass workshops. So infect they’re copying exiting art works, unlike in the medieval period where they don’t have the benefit of mass produced engravings and stuff to copy. This panel is the story of Sorgheloos which is a secular version of the old testament story of the prodigal son. This guy, Sorgheloos, goes out, he inherits a whole bunch of money, spends it on wine, women and song. And in the end, all he has left is an old woman, two starving animals and a bunch of straw to eat. So unlike the prodigal son he’s not welcome back with the fatted calf. What also happens in the middle of the sixteenth century, these chemists as we would call them today, alchemists as they were known, developed more pigments that could be fired successfully into glass. In the medieval period it was just that blacky-brown iron based pigment. Now we have enamel colours. So we have the greens and all the shades. Red and all the shades. Blue and all the shades. And the yellows. CG: It must have been a wonder to behold, a sort of technicolour movie. TB: Yes it was. That’s why they were popular. Also coloured glass was expensive and enamel paints are cheaper than coloured glass. So we are now in the age of just simply painting on glass. Think of it as a transparent canvas. Because that is where we are going, painting on glass. Let us jump forward to the middle of the eighteenth century. We have aristocrats interested in the gothic. Walpole made Strawberry Hill which was his idea of Gothic. And then In the early part of the nineteenth century we start getting academics in Oxford known as the Oxford movement. They were also called the Tractarians because they produced a lot of tracts. They are looking at medieval theology and seeing it or pre-reformation theology as a more pure form of the Christian faith. They are not advocating a return to catholicism but they are advocating breaking away from the corruption that crept into the English church in the eighteenth century. Shortly after, a complimentary, although at times, rival group, grows up in Cambridge known as the Cambridge Camden society, but also known as the Ecclesiastics when they are sitting in London. They were interested in pre-reformation theology, but more importantly in pre-reformation architecture and church furnishings. So you have in Oxford, the academics looking at theology. In Cambridge, they are looking at the physical structures of the furnishings. So we are at the beginning of the nineteenth century at that time when people are looking back to the medieval world and things done in the medieval manner. So this is where the Gothic Revival begins. Also in 1824 the Government passes what became known as the 600 churches act. Christianity had fallen into corruption in the eighteenth century. The church fabric itself, the buildings were neglected. There were a lot of people assigned as clerics in churches who just stayed in their country estates and took the money and they didn’t even maintain the churches. So the government steps in and makes a proclamation, effectively going, thou must build churches. Into this comes the great architects like Butterfield, Street, Pugin. So the very first half of the nineteenth century is what we know as the Gothic Revival. Church building, church furnishing going on and stained glass starts apace. Also in the 1850s and 60s craftsmen were thinking why can't we do it like the medieval stained glass makers. They couldn't simply because medieval glass is mouth blown. So there is no evenness in its thickness. Each bit of glass that the medieval craftsman made, this bit is thin at one end, but it might be thicker at the other. So that when you put it into a window and light comes through that little bit of glass, the light will come through differently. It will be less bright in the thicker bit and more bright in the thinner bit. The medieval craftsmen knew that. That's what the Victorian stained glass makers were really trying to discover. TB: Nathaniel Westlake was a freelance designer. You could make a living by doing that. He went around to companies like Powell’s who were probably the biggest manufacturer of windows at this time. He would show his portfolio of how good an artist he was. Also a portfolio of stained glass design that he could offer to them. And that is how he was making his living. But in about 1858-59, clearly by 1860, he had become involved with the stained glass firm of Lavers and Barraud. In 1864 the V&A had an exhibition of stained glass and mosaics and one of the firms that submits things that were selected to be displayed was a panel made by Lavers and Barraud to the design by Nathaniel Westlake. So this is just made for an exhibition piece as far as anyone has ever been able to find out. It wasn’t actually a potential commission which a lot of exhibition pieces were. This just seems to be solely their own making and as it’s a design by Westlake, one makes that big assumption that it’s Westlake’s idea. The iconography of this panel was all in his head. We know that Westlake was friends with the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood like many groups in Europe were interested in things medieval. They’re looking at more literary subjects. Morris and co were doing lots of things like George and the Dragon windows. Dante Alligheri, the writer of the famous Divine Comedy, from the early part of fourteenth century was big. There was a lot of interest in him. The iconography of the Westlake panel is quite complicated. It is derived from Dante’s Divine Comedy. In this poem Dante was granted a trip through hell into purgatory and finally into paradise. It’s a wonderful story. Dante is lead by the Roman poet Virgil who to him represents reason and as Dante is going through hell and purgatory he is reflecting on his own life. He is working out his own sin. At the very end of purgatory, this person called Beatrice starts to be mentioned. Beatrice was a real person, Beatrice Portinali. It seems that Dante knew her when they were children in Florence. He was a member of one family and she was another. For whatever reason and remember Italy wasn’t a unified country, it was a bunch of city states and these city states had noble families fighting each other. So marriages were not love matches, they were political matches and Dante had fallen in love with this young Beatrice. Madly, head over heels, quite perversely. Like, get over it Dante. But he never did. But he couldn’t marry her. She married someone else. We don’t even know if she realized his devotion. But anyway she had to marry someone else and she died quite young. So he was stuck on her all this time. Now when you read the Divine Comedy it becomes apparent that Beatrice is divine love. And divine love is the only way you can go through heaven. Reason cannot take you into heaven. So at the very end of purgatory, before he makes that last crossing of the river and going up into heaven, Dante is given a vision by a woman called Mathilda and her companions, often known as the three graces, but really faith, hope and love. They give Dante a vision of what is to come. And this is the first time that he realised that this woman, who he has always loved and is now dead, has become divine love. This vision of Beatrice is going to lead him into paradise. This is what is depicted in the panel designed by Westlake. Beatrice up there in that top left corner. Faith, hope and love are those three figures who are often referred to as the three graces. First personified in that form by Sandro Botticelli in the middle of the fifteenth century in the Primaevera painting. This is Dante kneeling at the front, eyes closed, given that vision of Beatrice. That moment when he realises that his love has become divine love and so will take him into heaven. It’s done in the medieval manner. So we’ve got little pieces of glass just like in the medieval way, irregular shaped pieces carefully chosen. It’s not just take that one, put it there to make the picture, but trying to get the right balance of light coming through. By this time in the nineteenth century they are using the equivalent of light cables. So they can start to see the effect and so they can choose the glass, arrange the shape in order to maximise the light coming through. So Westlake is the culmination of this late eighteenth century, first half of the nineteenth century, Gothic revival way of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval craftsman. He is a medieval artist. Let’s put it that way. Lavers and Barraud are a workshop that operated in the same way as a medieval workshop would have done. You have a centre in which you had your designer, your painter, your glass maker, your lead worker, all in one institution producing the window and each one being prized for their skills. As the nineteenth century moves on the designer becomes more of an artist. You start to get into, what is known in the ceramic world, as art pottery. You might as well call it art stained glass. Four film stills from Vision of Paradise, 2015. 30 minute, high definition video.

Outside the builders are laying bricks and installing windows. In my studio all is calm. I've been in listening mode and am currently transcribing two audio interviews.

The first was with Joanna Sutherland, Associate Director at Haworth Tompkins and project manager for More West housing development. It's fascinating to hear her talk about the visual appearance of the building taking shape opposite Latimer Road station. She explained the significance of a special Dutch brick called Bronze Grun. "The appearance of the brick, the tonal variation across the brick and the right mortar colour are absolutely crucial to the success of the project." It was not however easy to replicate trial samples and meet the original planning requirements. "We were in no way going to allow anything to go through that wasn't perfect. And if you look at mortars, different mortars of brick, it completely changes the appearance of the brick. So even now when you still see the area that has got the salmon pink, you can see it's a nice brick, but it doesn't look very good. And where the mortar's right, it looks fantastic." My second interview was with Terry Bloxham, Assistant Curator for Ceramics and Glass and the V&A. She gave me a superb tour of stain glass from the medieval period to the present day. This provided context on a Nathaniel Westlake panel, The Vision of Beatrice, that I'm using as inspiration for my project designs. "Westlake is the culmination of the Gothic revival. Of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval artist." "In the panel we've got little pieces of glass, careful chosen. It's not just take that one and put it there to make the picture. But to get the right balance of light coming through, maybe the ones on the bottom are thicker, thinner at the top. Before you put it all together in the lead framework, other techniques are used, like painting, and staining and etching." The Vision of Beatrice illustrates a scene from Dante's Divine Comedy. This is the climatic moment when Dante's love has become divine and he can be transported from purgatory into heaven. Recently, I met buyers of one and two bedroom flats at the development. Young professional workers who were excited about moving into the area. They wanted to know about local facilities and views from their flat. I could comment on the former. Hopefully they were pleasantly surprised to hear about the the complex social history of the area and having the Notting Hill Carnival right on their doorstep. I wonder if they will experience divine love (or otherwise) in their homes. Let us hope so. Future artists and historians will interpret and tell a story. In time. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed