|

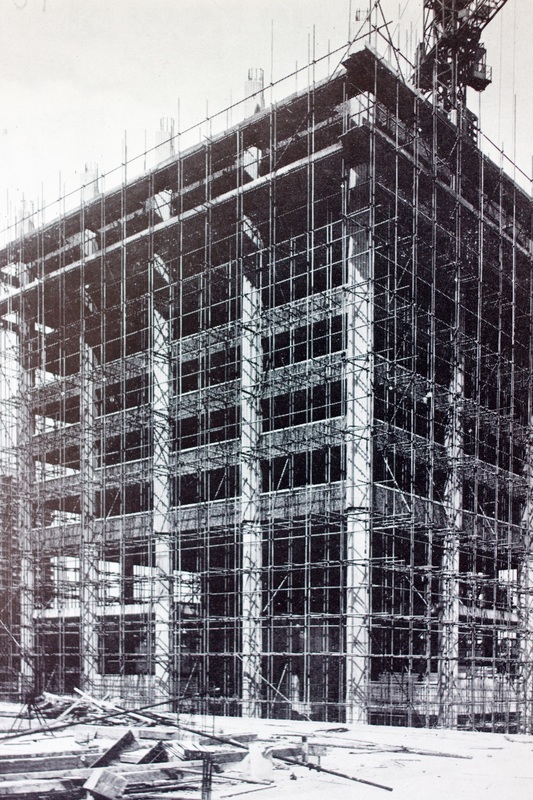

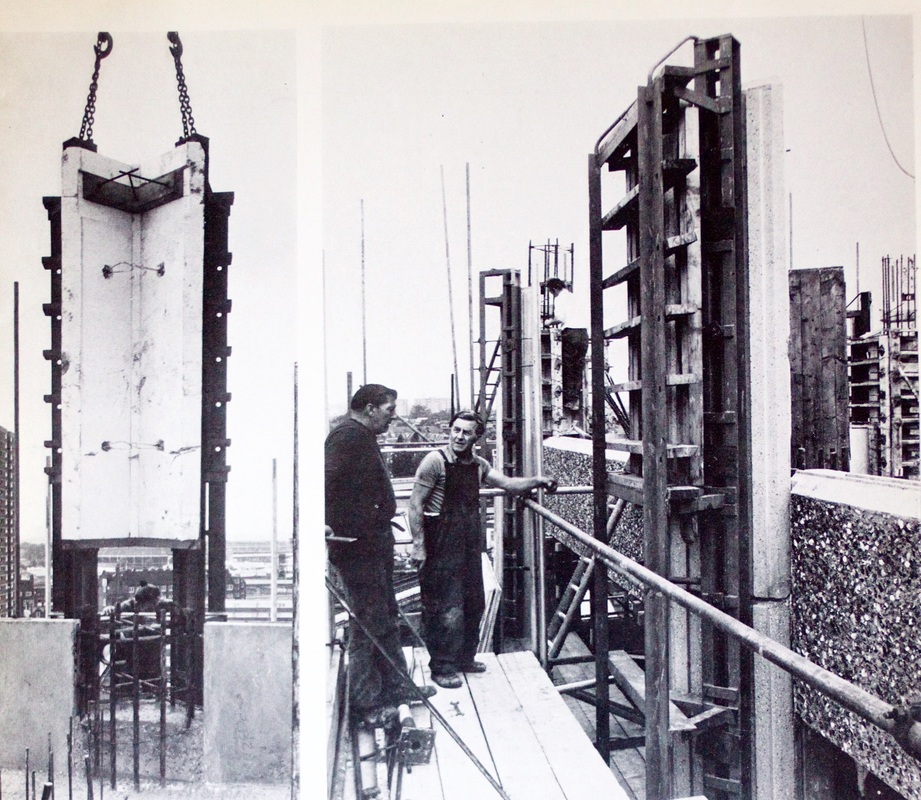

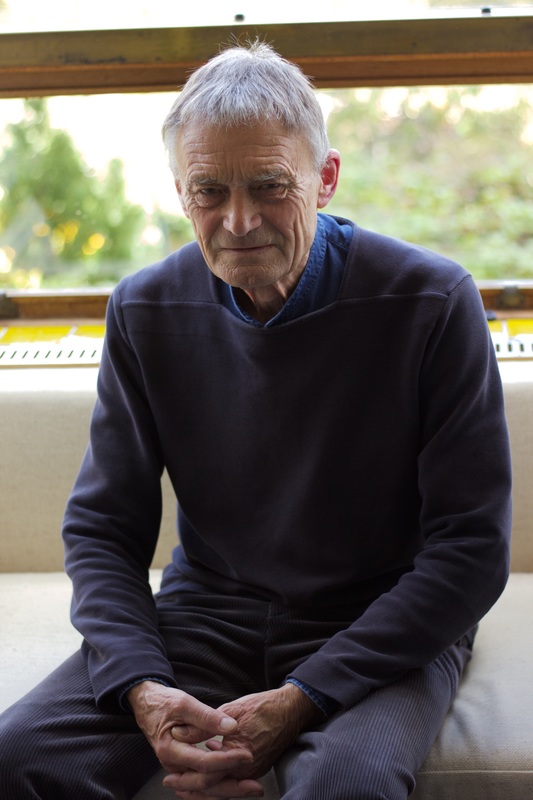

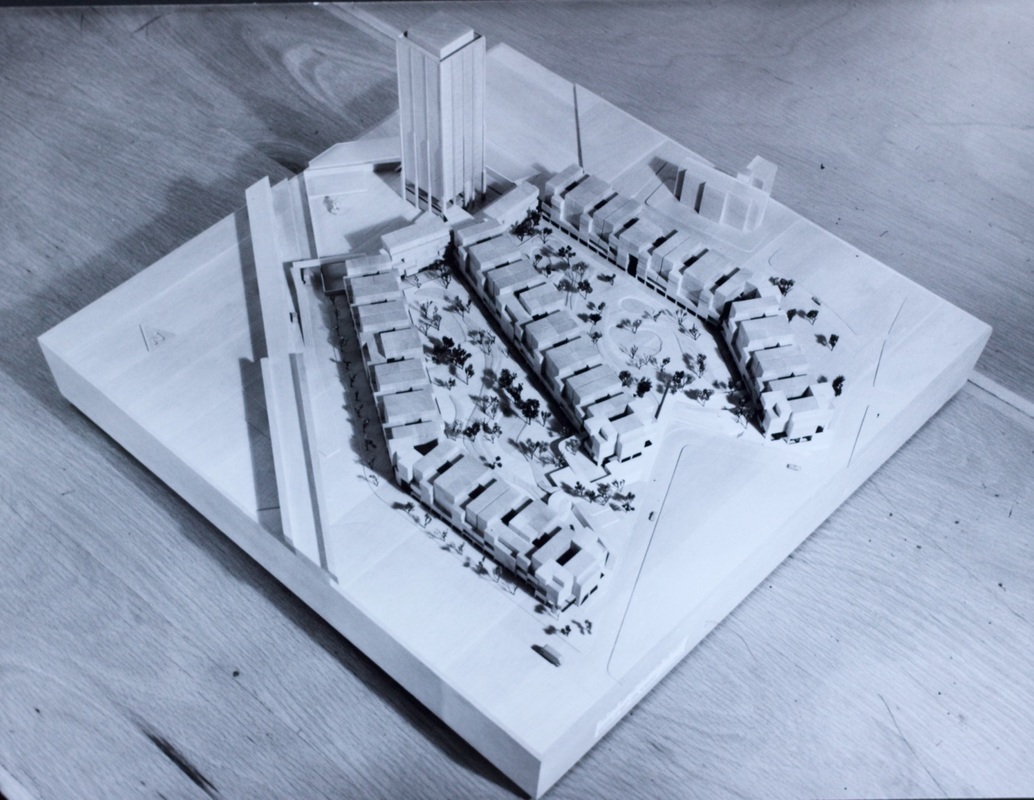

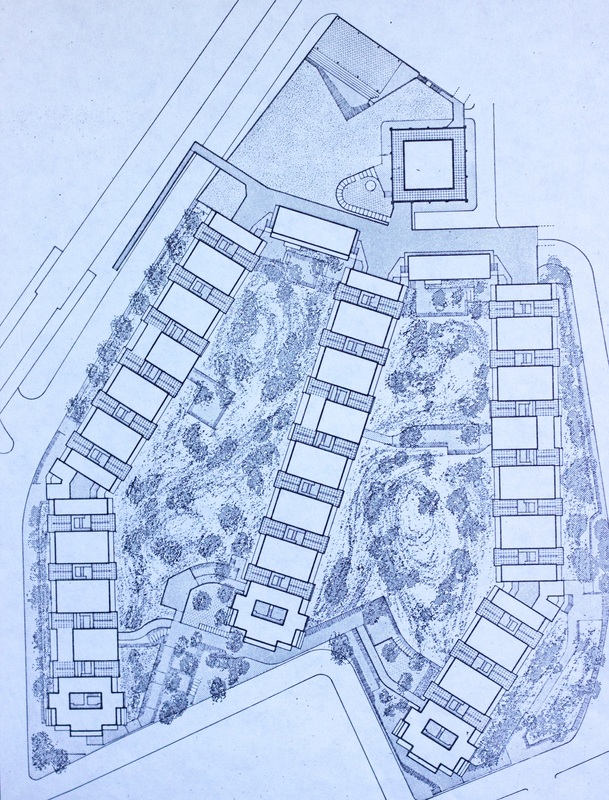

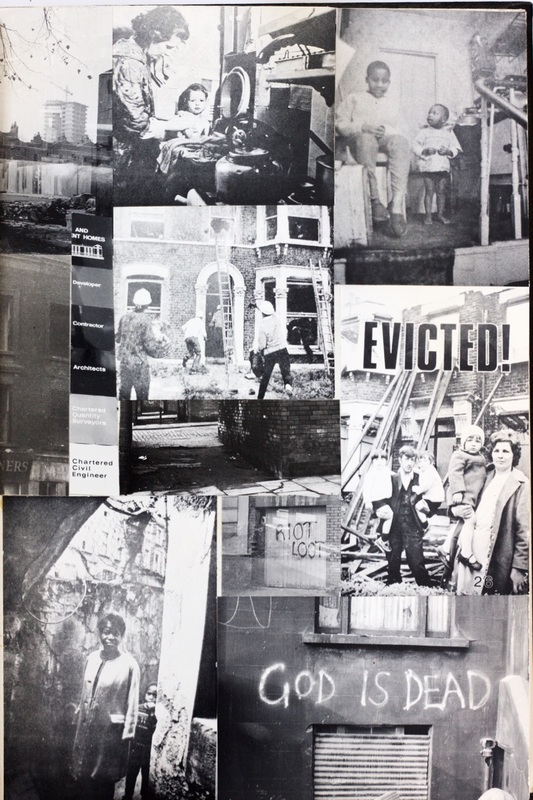

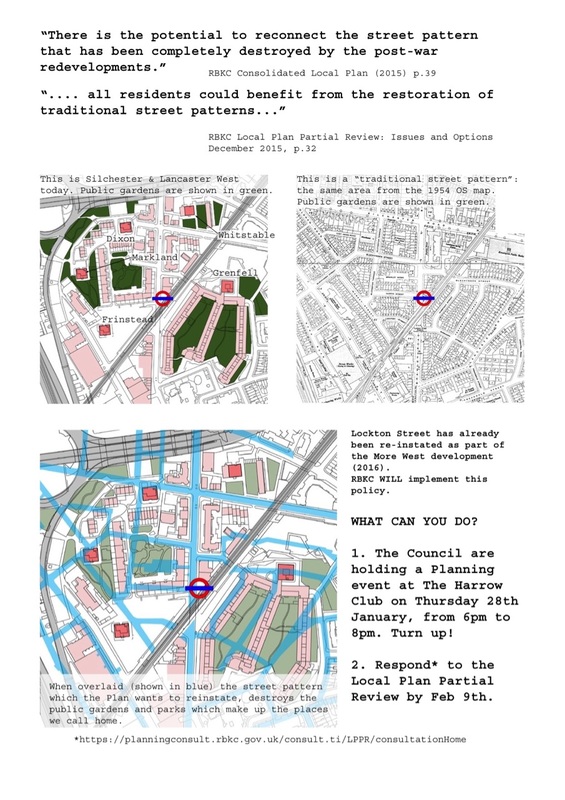

I've been working on Lancaster West estate for well over a year now. My commitment extended beyond the commission I had from the TMO (who manage the Royal Borough's housing stock) to make a mural for the new community room and a short film documenting the regeneration of Grenfell Tower. At the beginning, I was naturally regarded with a degree of skepticism. Why do we need an artist on the estate? But after attending numerous residents meetings and putting on art events in lift lobbies and during fun days, I earned my stripes in the community. During my tenure, I've had an opportunity to strike up many friendships across the estate. I offered them an accessible and sociable art. In return, several of them have entrusted me to render their remarkable life-affirming experiences and energising humour. More of these residents to follow. But first let's talk about regeneration and architecture and conclude by weaving both of these back into the beating heart and soul of Lancaster West. As of writing, Grenfell Tower improvement works is well nigh complete. After a £10 million regeneration, nine new flats have been created and offer affordable rents in an area where property prices average over £1 million and one bedroom flats on nearby More West are over £500,000. Each flat in Grenfell has had double glazing installed and a boiler for direct control of heating and hot water. The building has been thermally insulated with a new layer of cladding, although I miss the former design. The nursery and Dale boxing club also come back into vastly improved spaces and facilities. This upgrade to the fabric of a building is important in the context of how the council plan to regenerate this part of North Kensington. Silchester Estate, which is just across the road from Lancaster West, is currently being considered for regeneration. The initial options produced by the council were described as "nuclear" by estate residents. At a recent meeting in the town hall, several residents had the opportunity of making powerful statements to the council about the lack of consultation and the potential impacts of wholesale regeneration on the community and environment. The council listened and voted to explore the options in more detail. They also make a commitment to factor in the possibility of maintenance and infill. It is good to see how local residents are campaigning with a witty strap line (Gradual Change - In Due Course) that might have been culled from the insight of a former architect of Lancaster West, Derek Latham. He developed his ethos of urban renewal on a gradual basis after witnessing the impact of "slum clearance" in North Kensington during the 1960s and 70s. Previous blogs have featured interviews with Derek Latham and Peter Deakins, both of whom worked on the early stage design of Lancaster West estate. I can now present a complete documentary record of all the architects involved and their experiences, hopes and frustrations. One major issue was why the estate was never designed to its initial masterplan. This sense of fragmentation is perhaps the root cause for many of the challenges still being faced on the estate and which are being addressed by the newly formed Lancaster West Resident Association and the Grenfell Compact. I recently had the pleasure of meeting retired architect Nigel Whitbread and showed him around the estate. He lead the team who designed and built Grenfell Tower. It was the first time in over 40 years that he stepped foot inside the tower and enjoyed visiting a residents flat and those stunning views. What's interesting about Nigel's story is that he is a local boy through and through and not many local people seem to be aware of his role in the development of the area. We are also going to hear from Ken Price about the design of the finger blocks, the three low rise housing units that radiate out from Grenfell tower. Clifford Wearden is the design godfather of Lancaster West estate. I suspect his career path was adversely affected by the way the development panned out and not being the consultant responsible for all the later, much revised, stages. Chatting to his widow, Pauline Wearden, I was surprised to learn that, Clifford, like most other architects involved in the project disliked tower blocks. Grenfell tower was only included to maximise housing density levels; Nigel is an exception to this prickly high rise rule of thumb. This perhaps explains why Clifford in later life would drive over the elevated Westway and look across at the five tower blocks and declaim to his family that Grenfell tower exists no more and has been demolished for a new development. This is a poignant case of not wanting to see the concrete from the stone! Nigel Whitbread: I was born in Kenton near Harrow. My parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington. We moved as a family to this area in 1949 to be nearer the shop. I read quite recently Alan Johnson’s biography, This Boy. He is a Labour MP and former Home Secretary and interestingly was born in 1949. However his life and the poverty he lived through was in a different world, although just a mile away as the crow flies. He didn’t enjoy the family life that I enjoyed nor did he appear to enjoy his time at Sloane grammar school which I had done earlier. When I was going to leave Sloane, I didn’t know what I was going to do. One day I had an interview at an architect’s office. My eyes were opened. I liked the idea of drawing boards and doing something that I never understood to exist. The first firm that I worked for was Clifford Tee and Gale and that’s where I did my apprenticeship. I went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this I became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. I knew through delivering groceries that there was an architect who lived near my father’s shop. I told my parents this and my mother said she would speak to the wife of the architect who was also a partner in the practice. I went for an interview and got the job. This was at Douglas Stephen and Partners and this was probably the most influential time in my career. It was only a small practice but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that I worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. It was actually like going to a club and we were doing terrific work. Later on, I went to work with Clifford Wearden on Lancaster West. At that time his office was a two storey building in his back garden. It was a huge job for a small group. It was unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. Clifford was a serious architect but had a flair about him. He’d been in the Fleet Air Arm and had a lovely Alvis car which was a convertible as I recall. He did have a very bad habit whilst he was driving of turning his head and facing me whenever he was speaking which I always felt a bit disarming. I found this quirkiness an attractive aspect in somebody who was very precise in most things he did. The whole scheme had been well prepared and thought out by the time I joined to lead the team in designing the tower. The design is a very simple and straightforward concept. You have a central core containing the lift, staircase and the vertical risers for the services and then you have external perimeter columns. The services are connected to the central boiler and pump which powered the whole development and this is located in the basement of the tower block. This basement is about 4 meters deep and in addition has 2 meters of concrete at its base. This foundation holds up the tower block and in situ concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams all tie the building together. Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968, had been built like a pack of cards. Grenfell tower was a totally different form of construction and from what I can see could last another 100 years. Grenfell tower is a flexible building although designed for flats. You could take away all those internal partitions and open it up if that’s what you wanted to do in the future, This was unusual in terms of residential tower blocks. I also don’t know of any other council built tower block in London or anywhere else in England that also has the central core and six flats per floor rather than four flats which is typically done on the London County Council or Greater London Council plans. We were wanting to put our own identity on this. The GLC built Silchester estate and I had nothing against that but this was so different in many ways. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, we thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. We used insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, lifted up and put into place with cranes and they were so much more quicker. In an architects mind, they want towers to be an elegant form rather than stumpy. This was a challenge and was why I introduced as many vertical elements within the fenestration as I could. The only thing I could play with was the windows and the infill between the windows. I treated it like a curtain wall, to get the rhythm of a curtain wall. We lost some of this verticality in the recent re-cladding but it’s not the end of the world. And the building is now better insulated as we had different standards then. The floor plans were based on Parker Morris Standards which they used at that time and sadly have gone now. These were very good standards for storage and the way furniture had to be included in the plans. It was delightful to hear that residents thought flat arrangements worked well and I saw the views recently which I always thought were terrific. I wouldn’t have minded living in a tower block myself. Tower blocks were criticized for not being suited to people or a lot of families were being forced into it and they were feeling more and more remote from the street and meeting other people. But there is another side to this and it always seemed to me that if American’s can live in tower blocks, why can’t the English? This is the first and only tower block I designed. This was also the first social housing I ever worked on. No social housing has been built since this and I’m very much against knocking things down unnecessarily. I had heard that there had been problems a few years ago with the heating and it was no good and talk of the whole block having to come down. And I thought, if my heating goes wrong, I don’t want to pull my house down. It’s a great shame that the basic concept for the whole of Lancaster West to have a first floor deck for people, shops and offices and parking underneath wasn’t seen through for whatever reason. This means that there remains a basic flaw. Clifford Wearden and Associates only built Stage 1 and the remaining parts were built by other architects. I don’t think the designers are to blame because there was a requirement that it was designed to have cars for every flat. We’ve all seen things have changed dramatically since then and now cars can’t be accommodated everywhere. After Clifford Wearden, I worked for Aukett Associates and I was there for 30 years until retirement. Recently I’ve become involved with my local residents association and committees in drawing up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan. We included the Imperial West site over in Hammersmith and Fulham because that was already impacting on our conservation area. Hammersmith wouldn’t agree to this but we continued developing the plans liasing with RBKC and residents. The Neighbourhood Plan includes objectives around shopping, housing, offices and conservation. We have also identified 3 existing unbuilt spaces which are now designated as local green space and cannot be built on. Latimer Road is included in the plan and we think that could be redeveloped to improve the area and have more housing put on top of the business units. We have to have housing somewhere. That’s where you could do it. But don’t build on our green spaces. The Localism Act which the Conservative government introduced is a very powerful tool actually. Residents are able to influence the way their area is developed. Ken Price was lead architect responsible for the team who designed and built the finger block units (Testerton, Barandon and Hurstway) which formed stage 1 of the building project. Ken Price: My origins are in Derby in the Midlands. I went to the School of Architecture in Nottingham which at that that time was part of the college of art and is now part of the university. I worked for a short time in Derby and then I was offered a job to work in North Africa in Tunisia. I went there for 3-4 years. I came back and worked in Nottingham for a while with some ex-students who had set up practice there and and then changed jobs in and around London. After Lancaster West, I worked with Casson Conder partnership and was job architect on the Ismaili Centre in South Kensington. Subsequently I set up my on my own and did small scale projects, mostly interior work and retired a few years ago. Clifford Wearden won the Lancaster Road West development in Kensington. After a bit of a hiatus, the commission was confirmed for what was called stage one and he asked me to go and lead the team as project architect for the finger blocks. I worked for him and Kensington and Chelsea to develop the original masterplan which predecessors had worked on. Clifford was extremely good at handing over and saying - look this is the problem, you solve it and refer to me if there is still a problem. He was very generous although he had the overall view and concept. I know that he was very sad that the development became a little bit like the Barbican. It was a grander scheme and there could well have been more productive elements which just didn’t arise. I wasn't involved in those preliminary stages of development, so I can’t speak too much about how that evolved. But I was aware that the Silchester Baths on the site became listed and affected the masterplan. I briefly saw the housing in the area before or after it was all painted white because there was the famous or infamous film, Leo the Last. Was it black or white? Why did I think it was painted white. The director was John Boorman. I think I must have seen it just before they did that and probably immediately after. After it was cleared there was no real evidence of life or to how it was. I don’t even know what the state of the dwellings were like and whether they were totally without facilities. At that time there were a number of schemes underway to deal with the housing issue, alongside the problem of car ownership .One could describe it as the deck system when cars were kept down below and freeing up the ground level or the raised ground level for pedestrian use and housing. It was part of the brief to provide that amount of parking and it did subsidise some of the other elements. My predecessor had sketched in a basic outline of the finger blocks. I took that on and developed up the detail of the individual housing units and the spaces between. I suppose we were interested in the intricacies of locking together volumes of accommodation in order to maximise the space of each dwelling. Also providing, to a degree, some private outside balcony or roof terrace on the top areas so there was an opportunity for people to have their own little bit of outside space as well as the bigger outside. I still have a small model of the finger block that was made by a friend of mine, a model maker. It shows the different accommodation elements by colouring. It was really a demonstration to the council on the mix of the different elements. Community garden between Barandon and Testerton Walk. A constant source of artistic inspiration for Constantine Gras and featuring as the backdrop for several of his films: Vision of Paradise. The landscaping was dealt with by Michael Brown (landscape architect, 1923-1996). Clifford was very determined to ensure that the landscape was taken on and he persuaded RBKC to employ him. I think one of the essential elements in the concept was this endeavour to provide as much open green space as possible by concentrating the housing units. The density was probably what was expected or required by local authorities at that time. The estate was designed to try and retain that as much as possible and the tower blocks were an element in that because you’ve got a concentrated stacking of accommodation which again added to the freeing up of groundscape. Although there were a number of tower blocks around at Silchester I don’t think any of us would have chosen to have incorporated the tower block but it must have contributed to this density issue and freed up the amount of green space that was enabled. I think the estate was built to a good standard. We persuaded a brick manufacturer called Ockley to make bricks especially for the estate which weren’t available. It was just at the start of the introduction of metrication and it seemed to me, in particular, that it would be rather nice to make life easier in measurement terms to have bricks that fitted the metric. So they are specially made, 30 centimetre long bricks. We wanted to use brick as the main element in order to connect perhaps with the past more than you would have done with clip on panels. It does survive time rather better than a lot of materials. I still imagine they look pretty good. They were very nice brick manufacturers. I knew there was a hiccup in the construction process but I couldn’t quite remember what it was. (The contractor, A.E.Symns went into receivership in 1975 at the very end of the construction of phase one). I can’t think of a building site where that didn’t arise especially as the construction was over such a long period. There were industrial dispute problems (three day working week and building strike), but not hugely disruptive as far as I can remember. In those days it was very difficult to get contractors to keep the site clean. Now because of health and safety issues, I think building sites are much better managed. It’s a shame they never built the planned shopping centre or offices. There was an expectation of community facilities including commerce and everything else in order to make the place work. I don’t think there were any warnings flagged up that there might be vandalism. It certainly wasn’t in evidence as it was completed. I visited after it was fully occupied and there didn’t seem to be any evidence of vandalism then. We never got any feedback as a practice on you should’t have done this or that. Perhaps we could have foreseen some of the possible problems. At the time disability access wasn’t an issue. It should have been but it wasn’t. Now that wouldn’t be allowed. You have to provide much more facilities. Unless the facilities are provided people will abuse what’s there and definitely need alternatives. Maintenance has been the problem in almost every area of social housing that was built at that time and subsequently. it’s one thing to realise and provide housing for umpteen people, but then to not maintain the estates or keep them going. It was very short sighted. That’s why social authority housing has all but disappeared because nobody is prepared to take on the long term issues. It was a product of its time in the way it dealt with a big housing issue, sub-standard housing. And hoping to provide the mix of urban renewal, accommodation, green spaces for enjoyment, kids playing and all the rest. This was just one of a number of schemes which were resolved in different ways but the deck idea was a sort of constant thing throughout. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Estate, which is due for demolition now, was one of the background influences on the concept of Lancaster West. There was also a reference perhaps to the Lillington Gardens estate just off Vauxhall Bridge Road. That’s a famous development by Darbourne and Darke which I think still survives very well. Ideas of large scale redevelopment and housing tend to go through different phases of acceptability or relevance and it’s very difficult to look back and say that was the right decision to make. In some cases it was the only option either because of financing or government pressure or politics. But I would have thought that if the masterplan was completed it would have provided a better result than has eventually arisen. But it’s very difficult in hindsight ever to say. Pauline Wearden whose husband was the lead architect for Lancaster West estate masterplan and building stage 1. Pauline Wearden: Clifford was born in Preston, Lancashire in 1920 to working class parents. His father was a plumber and his mother was in retail with a profitable cafe. Clifford was his mother’s golden boy and she paid for him to go to university. There were no architects in the family. It just came thorough Clifford. Clifford studied architecture at the University of Liverpool from 1938-40 and 1946-48. He was very fortunate because that was a prestigious university in those days turning out many famous architects and Rhode Scholars. When war broke out, he immediately volunteered. He had a lovely war, mostly cocktail parties. No. No, He did have a lot of tragedy and he saw his best friend shot down. Clifford was a pilot in Air Command. He had travelled as a student on what they call the Tour and he’d been to all the classic places but during the war he also saw some exotic places. From 1949-54, Clifford was chief-partner for Sir Basil Spence. This was when they got the commission for rebuilding Coventry Cathedral and Clifford was given the job of preserving the ruins. He was very proud of that. I don’t know what brought him to London. But he had no home and went to International House Hostel. He lived in a hostel for years. He didn’t have anywhere stable until he bought his top-floor flat in Argyll Road, Kensington. Then he came across this derelict house on Homer Street, Marylebone. They were a row of 6 Georgian houses in that street and the property owner wanted him to do up the other houses as well. So he worked on those and then bought one of them. That was probably one of of his first jobs alone. By the time I came on the scene in 1965, Peter Deakin was there and Derek Latham was a student. Clifford built an office at the back of the house. A very nice studio designed by him which was contemporary which might have looked strange at the back of a Georgian house. This is where the master plan for Lancaster West was prepared. Eventually the practice had to relocate premises as there were twelve in number. It was like I married twelve men because they were always in our house. Clifford came home one day and he said they are blowing up one of the houses in North Kensington. And we said - what! And he took us all in the car at night. The director was just about to film the house being set on fire and demolished. They had all the safety people and security and police vans. We had to creep through the security set up. Nobody had invited us but we said we wanted to see it. They had built a false house to make a cul de sac and when you looked it was completely false, but it didn’t look it. So we were exactly there for the big bang. The children were thrilled. I can remember seeing big cameras, arc lights, just like you dream for an outdoor film set in the dark. It was typical of Clifford to have the children up. He didn’t want them to miss anything. However, I don’t think Clifford ever saw the finished film, Leo the Last. He wasn’t particularly interested in films. Lancaster West was his first very big job. But he got into the mould very easily. He more or less expected it working with Sir Basil Spence and being up there with all the old Liverpool people. He was very much an architect’s architect and he felt that his time was coming. Some architects don’t like meeting their public, but he was very good at that. I think he listened to them. One of his ethos things at university was social housing. So he felt very strongly about it. Of course, affordable housing it’s called now. I think he’d be absolutely disgraced by some of the policies such as right to buy. However, I don’t think he was a socialist. I don’t even know his politics but he was fairly traditional in many ways. We married in 1969 and you took over your husband’s life or it took over you. He was doing very well in 1969 but of course it’s a hand to mouth existence. Your only as good as your next job and the 70s were quite stressful and then in the 80’s the work fell away. We had to economise and got rid of a car. We were trying to think of other ways to save money. It’s very difficult when you’ve been having a certain lifestyle and it worried him terribly. He used to worry about what might happen and I always felt that was a terrific waste of time. He lost quite a lot of sleep over some jobs. Clifford believed that the tower block at Lancaster West was demolished. We drove past it on the Westway. He said it’s no more. And I remember saying to him, that we should have gone to see it come down. In the family we all thought it had gone but one day my son said it was still there. I think he would have been relieved, quite honestly, if it came down. He didn’t want it built. He didn’t want to be in this era of tower blocks. He felt very strongly about vertical living. It wasn’t right. So I don’t think he took any pride in it, except that it was not a bad building and it did work. I’ve never really appreciated that Lancaster West was landscaped or intended to be. In the model of the estate that my son has hanging from the wall in his house, there are little trees made by Ken Price. And they always put trees in as their panacea for making it look homely. But it did look good in the end and not as desolate as it might have been. I’m afraid to say that driving past on the Westway is the nearest I’ve ever got to seeing the estate. I’ll have to go. The best way is to walk around, I imagine. I'm going to end this essay with a few extracts from residents who live on Lancaster West estate. We are not now talking about perspectives and plans or so many housing units that can be redeveloped. We are talking about homes. People who have planted roots, raised their family and want to retire with peace and dignity. These flats and houses that were designed and built in the 1960s and 70s are now home to a diverse range of people who want to live in one of the richest boroughs in the universe. They deserve to have the final word. One hopes that in 10 or 20 or 40 years time, that they are still living in the area, as the new kids on the block are contemplating how to buy into the next cycle of housing redevelopment. Christine Richer, resident of Hurstway Walk: My mother was an African-Welsh woman and my father was black African American. They met after the war in the West End. Two weeks after my 18th birthday, I came to London and I landed in St Stephen’s Gardens in North Kensington. Massive, one room bedsit with the kitchen in the corner and the mice. The mice were hell. That was my first living in a big city. I came to the estate in the 70’s. Funny story. The first day I came here to meet the electrician and the gas people. No one turned up. I end up sleeping on the floor. And I had the most vivid dream of my life. I wake up in this dream watching my coffin being carried down the stairs. I saw these two shapes and they were my daughters. But it was very pleasant. I thought this is my place. My place on earth. I’ll live here till I die. As a child, I moved a lot. In Grenfell Tower there was a really nice club, like a residents social club and my partner at the time was on the Committee. That was my first introduction to the estate. It was full of different people who knew each other from the neighbourhood: Moroccans, Africans, blacks, whites, Portuguese, Spanish. I think with my involvement in the resident association and Estate Management Board, when the children were young, they have learnt a sense of community. They would always come and help me if I say I’m doing something with the R.A. Volunteer themselves, wash dishes. The garden down there was very important to me and the kids. They spent their formative years down there with or without me. We had family parties, barbecues. That living space outside there meant a lot to me. I do believe that we are going to get knocked down as all this gentrification is happening all around us. And we are not a Victorian block which is a beautiful thing. We are a 1970s fling them up, fling them down block. I don’t know where I’ll end up. That’s the biggest concern for me. That makes me stay awake at night. That makes me cry. If they could build another block, 4 or 5 streets away, where I knew I was going to be rehoused. It could be Manchester. All my close friends who live on the estate, only about 3 are here. Everyone’s gone. It’s a changed community. I haven’t always loved all the neighbours. But the neighbours that I have liked and I’ve made friends with, we’ve loved living here. The old families who brought up their kids and their kids have grown up and moved away. It’s been a home to a lot of people. Edward Daffarn, resident of Grenfell Tower: I’ve lived in Grenfell Tower for over 15 years now but I’ve lived in North Kensington, Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill Gate, my whole life. I found education was quite a therapy. I became a social worker for about 7 years. And then sadly my mum, got motor neuron. so I gave up work to look after her. I haven’t got back into social work. But what I have got involved with is housing issues on Lancaster West and in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The stuff that we’ve been doing on Lancaster West started as a result of the Academy being imposed which was 5-6 years ago. When we first started there was virtually no community groups around. Five years later there's a lot of community activism because of what’s been happening in housing. Westway 23, Focus E15 Mothers, The Guinness Trust down in Brixton, Our West Hendon, Sweets Way and all the radical housing network. There’s all these different struggles. On the 24th June, this year, 2015, the council passed a motion in the full council meeting saying that they were going to go ahead with the destruction of all low density social housing in North Kensington. Low density means this, They’ve been built nicely, giving people some space inside and with some green residential amenity outside. Trees and green space for their children to play in. Low density housing. It’s not anything else. It’s just nice estates. It will be interesting to see what will happen to Silchester. Because sooner or later, one community is going to say, and it only needs one or two inside that community to lead the rest - just to say - your going to knock our houses down - oh yeah! Oh yeah! Let’s see about that. North Kensington has a good history of not just taking these things lying down and when people finally wake up and realise what is going on, maybe the council will get a bit of a shock. They call Lancaster West the forgotten estate. And it hasn’t been called the forgotten estate for the last couple of years. It’s been called the forgotten estate ever since I’ve been on here. If it had been maintained properly, Grenfell Tower and the finger blocks are quite beautiful. Particularly if you live here. I don’t know the architect that designed them but they have architectural merit. I don’t know how you say you love your home. You love your home. If we remember what happened in 1974-75 by the signs, Get us Out Of this Hell, then maybe the Grenfell Action Group blog, the protest that we did going up to Holland Park Opera, the procession of Westway 23 along the Westway, will be things that in 25 or 30 years, people would look back and say, when they took away the stables, the Westway Stables, when they took away the children’s centre, didn’t people say anything. And they get on the computer. Look I found this Grenfell Action Group. Yeah they did something, And they did this demo. That will inspire the next generation of people who would care about their community. Clare Dewing, resident of Talbot Grove House: My parents were squatting in and around the area. Mum became pregnant with me and said right Paul, get us a flat now. My first steps were actually in the flat that I live in right now which I share with my mum. When my mum walked into an empty house, she put me down. I stood up and apparently I ran just clean straight across the room and those were my first ever steps. Growing up on the estate, we were told never to leave the estate because I’ve always viewed the estate as two halves. My half which is Talbot Grove house, Verity Close and the other half, the finger blocks and Grenfell. So when we were a bit naughty, we used to go on the other half and do knock down ginger and stuff like that. I did probably knock on Christine’s door. About 1993-4, I was quite naughty and I’d be going to clubs, sneaking out. Mum and Dad wouldn’t know and my friend would say she’s staying at my house and I’d say she was staying at her house. Teenagers you know. I do remember it being quite scary trying to sneak back into Ladbroke Grove and we got mugged a couple of times, got followed a couple of times. But in recent years, I do feel the safety has improved. There used to be crackheads on every corner, all along Portobello. But that kind of edginess gave it a vibrancy which unfortunately, I think, it’s almost gone. About 5 years ago unfortunately my dad became ill and I moved back to my parents house to look after my dad. We’d always known that my mum’s memory wasn’t too good. But it was only after my dad died that we managed to get her to have a full proper diagnosis that it was early on-set dementia. Mum’s going well. I think the progression of her dementia has slowed and I think that’s down to a combination of exercise, good food, good stimulation. I wanted to join the R.A. because it got me to kind of flex my muscles again in using organisational skills in a different way and and just giving back to the community that’s helped me out so much over these last few years. Kensington and Chelsea are an amazing borough to live in especially the way that they look after the older population. I also had a bout of depression as well and the services that were available to me are not available to some of the people that I’ve spoken to. So I feel that the support is there and that’s why I’m really surprised about the state of the housing here. It doesn’t marry with my experience of all these other services. I think Kensington and Chelsea need to be aware that if they just sell all the properties off and make it into a million plus houses, that what draws people here, what draws people to Notting Hill, what draws people to Portobello, would just be gone. It is that mix of culture that drew people here in the first place. That made it trendy. That made it hip and cool to hang out on an evening. It’s just going to turn into Kensington High Street and be replaced by Cafe Nero’s and shoe shops and places you can’t actually afford to shop in or buy food in. What we are trying to do as a RA here is to lay the foundations now. We're trying to get ourselves prepared and ready so that when the regeneration does come that we are ready and we've got some ideas together. Hopefully we can influence them which would be great.

9 Comments

It was a pleasure to meet up recently with Derek Latham at Lancaster West estate. He worked for the architectural firm of Clifford Wearden and Associates in the late 1960s making detailed drawings for Testerton, Hurstway and Barandon. These are the low rise housing units that radiate out from the central high rise tower and are known to locals as the "finger blocks". You might recall a previous blog featured Peter Deakins who was responsible for designing the early master plan. The planning and building process for Lancaster West was very protracted (1963-1981) and both architects left the practice before the first brick or concrete deck was layed They had different experiences and memories: Peter expressed frustration that the original plans were never built including a radical plan for building around Latimer station and connecting this with housing and a shopping centre; Derek campaigned about the housing crisis in North Kensington which the social housing development at Lancaster West was supposed to remedy. Ahead of out meeting, Derek kindly sent me his 1973 thesis: Community Survival in the Renewal Process - An integral part of the housing problem. This is very topical as RBKC council are currently consulting on a major regeneration at Silchester Estate and that will probably extend to Lancaster West in due course. The following are excepts from a statement provided by Derek and also an audio interview recorded at the estate. There are some fascinating comments about his involvement in the area and how it shaped the development of his philosophy of Gradual Renewal. "It’s wonderful to just come and experience the estate again. It was really interesting to see how the streets in the middle of the finger blocks have been altered and you feel they are ready for another transformation. So lovely to see that the green spaces between the blocks is just how we all envisaged it. The trees probably need thinning a little. Lovely in the winter, but in the summer I think there is probably just a bit too much shade. I have to say, the outside of the tower block with its new cladding looks really good and the academy is very impressive. At Lancaster West we tried to create scale and massing similar to that of a London Georgian square, but keeping the cars under the buildings so that the spaces between the building could be car free and provide a recreation and play space for those living around it. It was difficult to achieve the required density without building a series of tower blocks as was being undertaken on most other redevelopment schemes at the time. Our philosophy was effectively to lay tower blocks along the ground (in creating the "finger blocks") and instead of the vertical circulation going up the middle of the block by means of lifts, the circulation went along the centre of the block horizontally by means of walkways. During the development I became concerned when I discovered that a large proportion of the existing tenants who lived in the area were not to be rehoused. This was because they were effectively itinerant tenants living in the Rachman owned properties. Often two families to a floor sharing a kitchenette and sometimes six families sharing one bathroom and toilet. We think housing conditions today are poor, but I wish I had the photographs to show you the appalling conditions that these people were living in. They truly were slums. Not because of the way they were originally built as fine townhouses for single families with their servants but because of the way they were being exploited with little maintenance and severe overcrowding as the housing shortage at that time was so acute. You could look at a film like Cathy Come Home which was made back in the 1960s which fully explains the situation at that time. Because of my concern at the situation I joined Shelter. But I could do nothing to help the families that were in the Lancaster Road West area, most of whom had already been moved out to create a "ghost town". In fact the area was used as a film set just before it was demolished. All the buildings were painted black to create a macabre backcloth for some form of thriller or horror film. I am sorry, but I cannot remember the name of the film - I never did see it. (Derek is referring to the 1969 film, Leo The Last). But the council's intention was to continue with the demolitions northward into the Golborne area. It was in this area that we worked with shelter to encourage the residents to fight for their rights and fight for the properties to be improved under the new housing improvement acts rather than demolished. This was action that was taken directly to both the GLC and the borough. I remember one occasion when the borough said it was too complicated to change from demolition to improvement and the protesters wrapped up the Mayor's car in red tape. Shelter had also fought against the construction of Westway. There was a political party at that time called Homes Before Roads which actually managed to get some councillors elected onto the GLC. There was another occasion I recall when some activists in the upper stories of the houses in Golborne that were so close to the road demonstrated their proximity by firing with air rifles at the tyres of the cavalcade of cars that drove along Westway when it was opened causing several punctures. People were a lot more active with their politics in those days. By this time I was passionate about the need for a better solution to housing regeneration than the large clearances that were occurring throughout all the major cities in Britain. My thesis had examined the large council estates in Glasgow (Balornack Road Estate) , Liverpool and Manchester. But it also examined innovative improvement schemes rescuing tenement blocks in Glasgow, back-to-back houses in Leeds, and community housing in Liverpool 6 under something called the Shelter Neighbourhood Action Programme (SNAP), as well as some housing improvement being undertaken in Wandsworth by Ted Hollamby in the Brixton area. These demonstrated that communities survived better through the redevelopment process if they could remain where they were. Hence I developed the philosophy of Gradual Renewal - simply removing the very worst of the houses that were in poor condition and replacing them on the same street with new houses fitted in between those that remained. The philosophy was that in 15 or 20 years when some more of the original houses reached the end of their economic life then these too could be replaced. This would utilise the hammer and chisel and a small-scale builder rather than the bulldozer and the tower crane. It would avoid the decade of disruption that occurs with clearance and redevelopment. When I was first involved at Lancaster West, there was no question that you just pulled slums down. They had been doing it since the 1930s and it was very important because in those days the houses were really badly built. There aren’t slums now. There are estates which have been vandalised, but more often neglected. Maybe because they are more expensive to look after than other estates, so they don’t get that extra money. But in the long term maintaining places is cheaper than pulling them down and rebuilding them. And that’s without taking into account social costs. In my experience the disruption to the community is usually not less than 10 years from the start of a development to its end. This is a good part of any child’s life. What are the consequences of that? They are enormous and they don’t get costed. That’s why to keep communities together, you need to make the change frequent but small scale. And to have a long term vision for slow redevelopment in stages. But the idea of wholesale redevelopment, running everything to the end of its life, is going to cause problems for people. I don’t know about the condition of Silchester estate but Lancaster West is good solid brick work construction. It's not some panels that are held together with rusting joints. I know in some cases quite a lot of the GLC housing estates had that inherent problem and that was never going to get resolved. You just have to say we cannot repair it. It if hasn’t got those sort of problems, why not find a way of achieving your objectives without pulling everything down. The principal should be to save and find ways of improving. How can we build an extra floor if we want to increase the density? How can we improve the walkways or insulation? Sometimes you might need to demolish certain portions. I wouldn’t be alive now without some pretty good surgery from time to time. But the point about the good surgeons is that they only cut the bits that absolutely ned to be cut and the rest of the organ keeps going. And if you look at any community estate, it's like a living being and will need some surgery. But surgery isn’t death by bludgeoning and waiting for a re-birth. Nobody survives that well. The current housing crisis is bonkers. It’s clearly about not building enough houses because they haven’t worked out a way to fund it. And I don’t fully understand it. There is a lot of capital tied up in this country and basically its not quite needing a PFI because that is for too heavy. All you need, in my view, is to give a reasonable tax break and guaranteed longevity to major institutions to be able to invest in housing. It is a lot of investment and it needs a long pay back period. It’s not a quick fix. But if you get it right, it should be a good fix. Social housing should have a stability to it that even private housing doesn't. People like the Peabody Trust can demonstrate how it's done. I can’t understand why the government has not taken that model and gone with it. Although it's a Fabian model, it still fits very strongly within the conservative ethic of using private finance to help people to do things and to see it as a long term investment. You could progressively allow a proportion of houses to be purchased each time as long as that money is recycled into the new houses. But that's got to be sustainable and they have never seemed to be able to get the model to work. " Campaigning poster designed by Dale Teller and circulated by We love the Silchester Estate.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed