|

Jordan Stone, film maker in conversation about his parents, Barbara and David Stone,

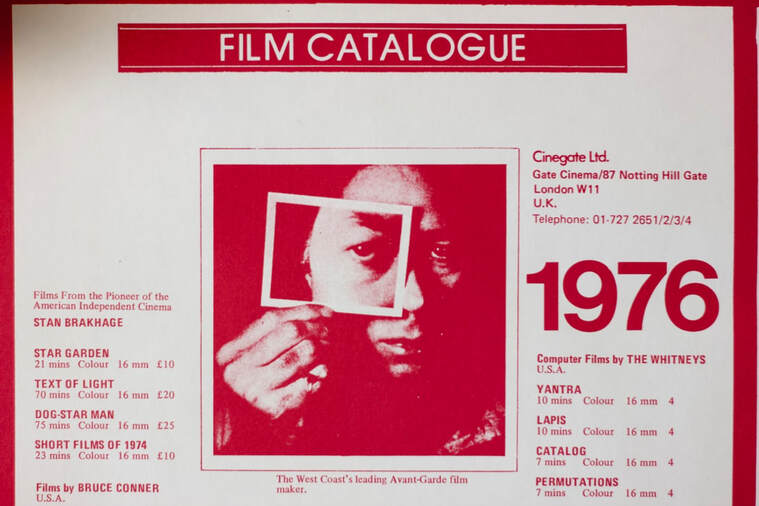

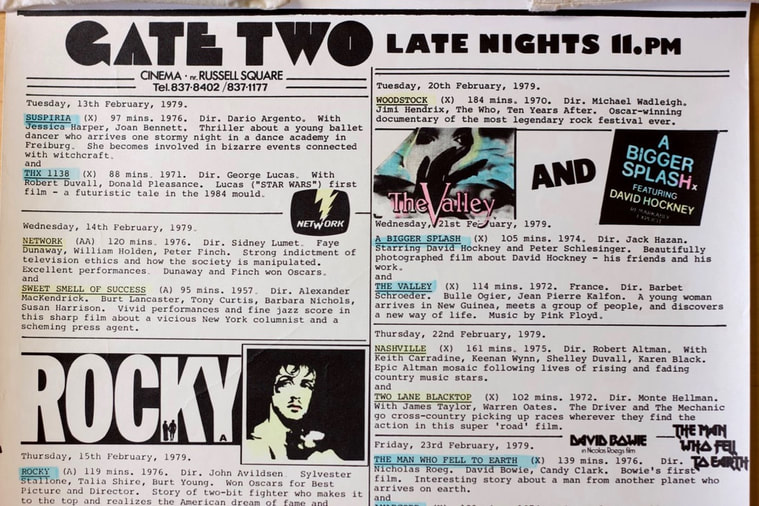

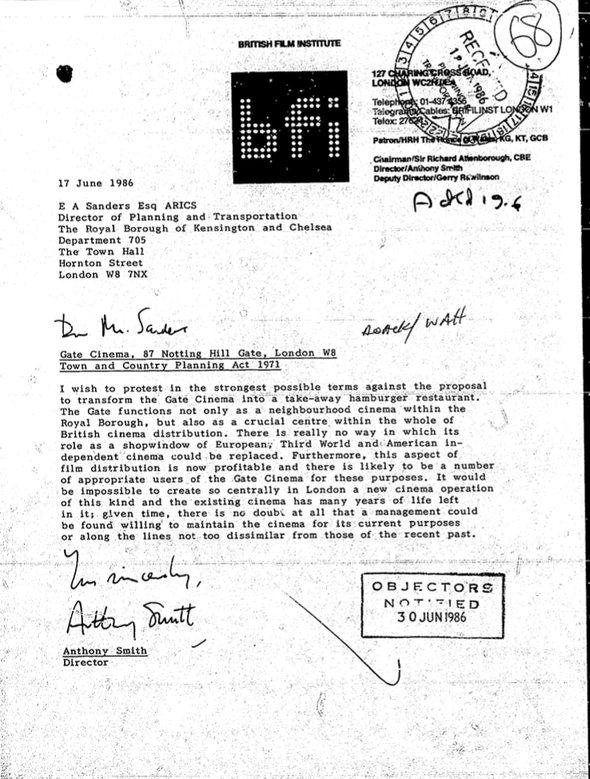

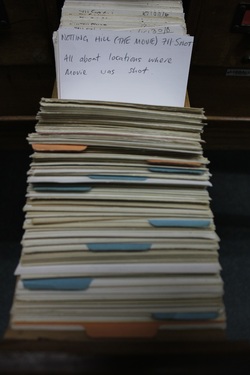

who opened a pioneering art house cinema in 1974 at the Gate, Notting Hill. The family moved to England in 1971. I think what my father originally wanted to do was to open a New York styled delicatessen in London where you could get bagels, cream cheese, smoke salmon, pastrami on rye bread. That was his original plan. But my parents had a passion for underground, avant-garde and independent cinema. They had been attending film festivals from the very early 1960s, whether it was Cannes or Venice. They were the creators of the Spoleto Film Festival in 1959. And so they were very familiar with European directors, the press, film critics, historians and writers. They had also been involved in the various film art movements in New York. They had made films themselves and also produced films with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. So at some point, they realised that there was this huge area that was missing in film exhibition and distribution. And that was their talent: to create a distribution and an outlet, a cinema, at the Gate in Notting Hill for showing these independent films. At that time films were still being dubbed for UK release. And there were films that would not have found a way out of their country of origin. My parents combined their passion with the business. But taste has to obviously come first. You have to create that and show it to the public. In America there is also a certain passive-aggressive approach to business whereas in England, it's a lot more passive. Maybe aggressive is not the right word, but they were more proactive, a term used today, but not used then. And so, it's like everything aligned at the right time. A cinema became available for them in Notting Hill. It was called the Classic. I think the previous owners couldn't afford to keep it going and that was the moment to strike as it were. What you have to realise is that the distribution company Cinegate and the Gate Cinema went together. What we distributed was what we showed. In the Cinegate catalogue, we had a huge collection of experimental cinema from Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Stan Brakage and the Mekas Brothers. And what also was remarkable were the late night double bills, mainly from other distributors, mostly American classic and cult films from the 1930s up to the 1970s. My parents created this culture of late night screenings that started at 11pm and went on till 2 or 3 in the morning. No one else was doing that. I still bump into people who tell me that they saw this film 25 times because they went to the late night program every other night. And unlike other cinemas, the Gate was open 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year including Christmas Day, New Year's Day. We were open every single day. Other cinemas started to copy us with late night programming. The Scala started doing the all-nighters at weekends. The Electric that was just down the road from us, on Portobello Road, was a repertory cinema. Peter Houghton who ran that cinema had perfect taste. It was an absolute fleapit at the time, but they created their own cult even before the Gate. But it was very different from our cinema. They would show a week of Hungarian movies and then ten days of German New Wave and then a week of Charlie Chaplin. And they showed a lot of films that we distributed that fitted perfectly into their programming. But they weren't opening movies. We were and they were independent, art house films. There is a nice little story. The Electric went through many periods of running out of money and my father insisted on lending them some. It was a real beautiful little moment unheard of that one cinema would help out another in the same area. I don't think my parents started up their operation thinking in a competitive way whatsoever as opposed to enhancing the whole concept of British Independent cinema. A few years later, once everything was going well, my parents had a good relationship with EMI and Barry Spikings, its head at the time. He had produced The Deer hunter and EMI had a cinema in Bloomsbury. But they had no idea what to do with it. They didn't know how to program it and so they gave it to my parents and the rent was completely reasonable. After a while, Gate Bloomsbury (now the Curzon Bloomsbury) was divided and had two screens. Then some short time after this, the same thing happened with Rank who had a cinema on Camden Road. My parents took that over and it became Gate 3. And finally, in the basement of a Mayfair hotel, there was this wonderful, tiny, super-exclusive cinema with just 40 or 50 seats. That became Gate Mayfair. When we first opened in Mayfair, this must have been about 1980, Mephisto, which was a huge success and went on to win Best Foreign Picture Academy Award, that was shown at Mayfair on a second run. I think it was playing for 9 months. My sister says it was shorter. But it felt longer. The majority of art house movies were definitely not American. The only American art house movies would be ones made by first time directors who sometimes had a distribution deal with a major company. And so the only way you would find out about these films was going to film festivals where the producers would be at Cannes, Venice or wherever they were trying to sell their films. My parents would be looking out for these types of films. Jonathan Demme was a Roger Corman protégé and his first couple of films we opened, I think we even distributed them. There was CB Radio and Melvin and Howard.

There were moments that brought great controversy that fed into the success and mythology of the Gate. Derek Jarman's first film, Sebastian, for example. The dialogue was in Latin and there were scenes of men making love to each other. It was definitely not pornographic, definitely an art film. But they were under a lot of pressure from the Board of Censors which was run by a guy called James Ferman, who was also an American. There wasn't much love between him and my parents. There were lines around the corner of the Gate Notting Hill because the only film prior to that which could be conceived of as a homosexual film was A Bigger Splash. That was a film about David Hockney and we ended up showing that at the late nights. But Jarman's film was a full-on feature film and made by someone we had never heard of. We had a lot of celebrities and famous people coming to see that film in 1976. And then a couple of years later with the Oshima film, In The Realm of the Senses, where you had two lovers making love throughout the film and in the end the girl cuts the man's penis off. That film was refused a rating by the Board of Censors. My parents came up with a way around this; which was to turn the cinema into a club. So people had to be 18 and pay a minimum 25p or 50 pence membership and then they could buy a ticket to see the film. But as kids growing up, we were told to stay away from the cinema because my parents were expecting to be raided by the Home Office every day. I also know that for that film to be seen, they put together a list of very well known people who had signed a petition demanding that this film be allowed to be shown to the general public. This was not just film people or from the entertainment industry, but also politicians.

The regeneration of Notting Hill had not happened at this time. That was much later. Everyone who was everyone was coming to the Gate. You had to imagine Harold Pinter living down the road and he would want to see everything. We had people who loved film and wanted to see films that the film critics were writing about and that would not otherwise have a chance in a lifetime of being released in its original form. We had punk musicians, artists and photographers, a lot of theatre people and of course, the general public.

My father was always charging a little bit more at our cinema. There was a reason for this because we were showing films exclusively. I think our first ticket price in 1974, for Fassbinder's Fear Eats The Soul that opened the cinema, was 60 pence; but after a year or two, this went up to 90 pence. And of course, we were an art-house. You were going to pay to see art. He wasn't trying to rip anyone off. It was a very exclusive approach however. And my father was actually quite short and the rows in the cinema were based on his leg- room. What he wanted to do was get as many seats in as possible. So we did have a reputation of having very thin rows, but that was based on the fact that he was quite short. I think we had 282 seats. If you look at the Gate today, my father would be surprised what it turned into with the sofas, the tables, the feeding and drinking during the film. I remember we were one of the first households that had a video projection system at home because film-makers from around the world were sending us films to watch. We grew up watching films that never made it into distribution. We had friends coming over to the house who never knew what a video was, VHS or Betamax. And we had equipment that was flown in from the states. This was set up in one of the rooms in the house, a screening room. Actually whether we lived in New York or London, my father always had a 8mm and 16mm projector set up in the house. Saturday night we would be watching films. They were very social events with film critics, Chris Petit, Nigel Andrews, David Robinson and filmmakers. We were also very friendly with someone who worked at the National Film Archives and every weekend he would come with a 16mm print under his arms, something that was 40 or 50 years old. My mother would do a big dinner and then we would all sit and watch the movie. That was a large part of the Stones' reputation. From the age of 11 or 12, I was working in the cinema and the Cinegate distribution dispatch office. Cleaning the films, packing them up and taking 16mm and 35mm prints to whoever was renting them. My brother and sister were also working with me in the cinema, making popcorn, tearing tickets and in the projection booths. I was also an actor and then at the age of 16, I had already started a video production company. Then a producer friend of ours asked if I wanted to be a runner on one of his films. That's how I started making my way up as an assistant director and have never stopped. I still am a first assistant director on feature films, commercials, and music videos. I was based in L.A. for a long time, too. And now I'm operating out of Italy. I look after a lot of the filmmakers who come to shoot here and I've turned that role into a type of service producer as well. I've produced projects with Sofia Coppola, Mike Figgis, Spike Lee. I’m a filmmaker myself. My films are not commercial and that is a result of most of my life working on other people's movies whom I've learnt so much from. The lesson that my parents ingrained in all of us is that you have to do what you feel is right - for you! And we grew up in an anti-commercial atmosphere. Anything that was American studio was the devil. We knew from the beginning that people who went to America to make films, compromised their creativity, because a producer or the studio said we want more tits and ass and more violence. However In the last 5-10 years in America, I've found that there has been a rush of films that are very independent. But most films can't be made unless they have a distribution deal. The film studios and media companies will put money into a film for its distribution rights. The filmmakers are not dictated to as badly if it’s a non-studio film because they have got the money just for distribution. So what's happened is that it's allowed much more of an independent approach to American filmmaking. There are many different structures to put a film together. You can raise money privately; you can raise money through pre-sales, through distribution sales, money from the studios, from several companies or countries. Tax incentives. It's a whole quagmire of things before you can get interest for the project. But if American studios are involved, the more control they have over the finished product. It's a different process for a European or a Chinese filmmaker. I saw a space to do commercially what my parents had done in London during the 1970s. I ended up for a while programming two cinemas in Milan in the same style as the Gate. I also created CinemaStone and this is not just a production service company, but it also dealt with film and event programming. I grew up doing what I was destined to do.

Barbara Stone Unpublished - trailer for film written and directed by Jordan and Veronica Stone

Jordan Stone's website Poster art work from the Barbara Stone Archive recently deposited at King's College, London And which will be available to view over the coming years Drawing by Constantine Gras: When a kiss fans out Watercolour, pencil, ink 9.5 x 12 inches, 1994 Link to film event called Emotion and Economics - A history of the Gate Cinema

2 Comments

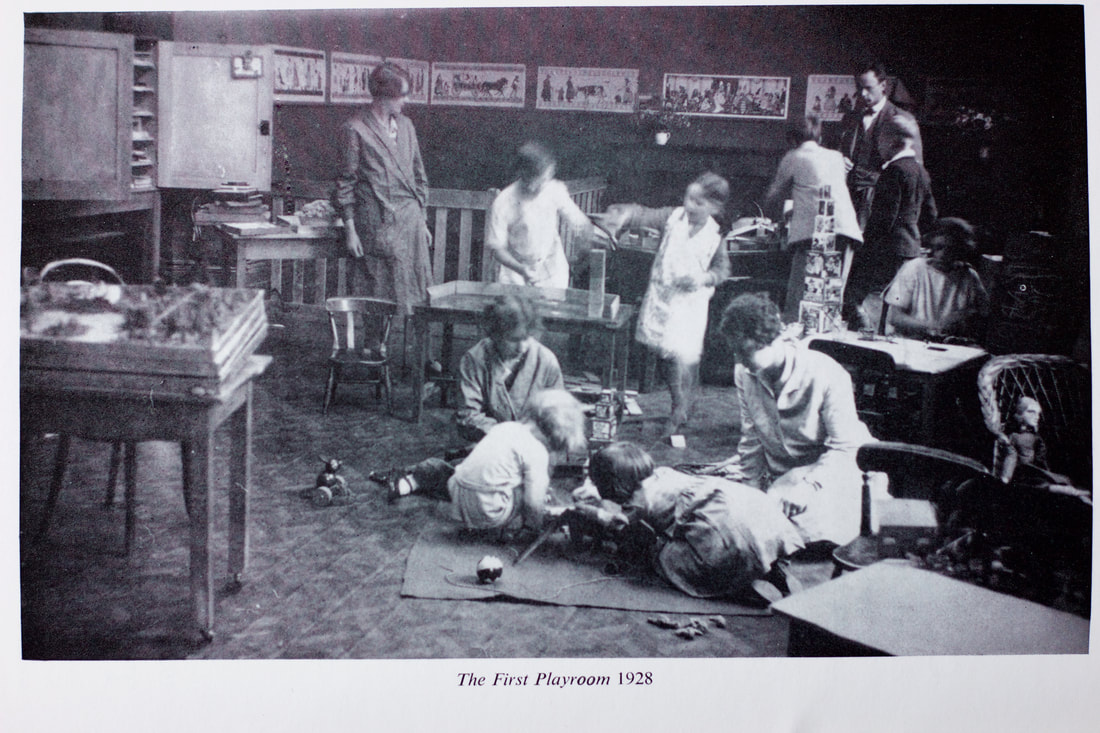

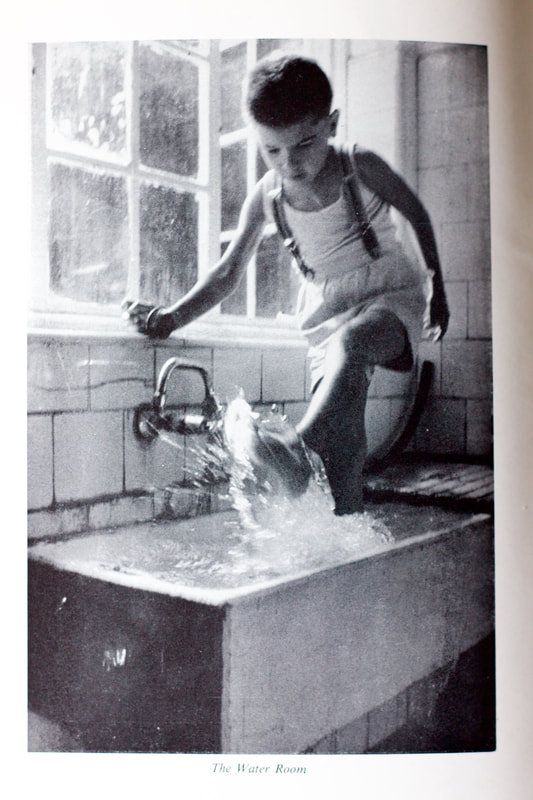

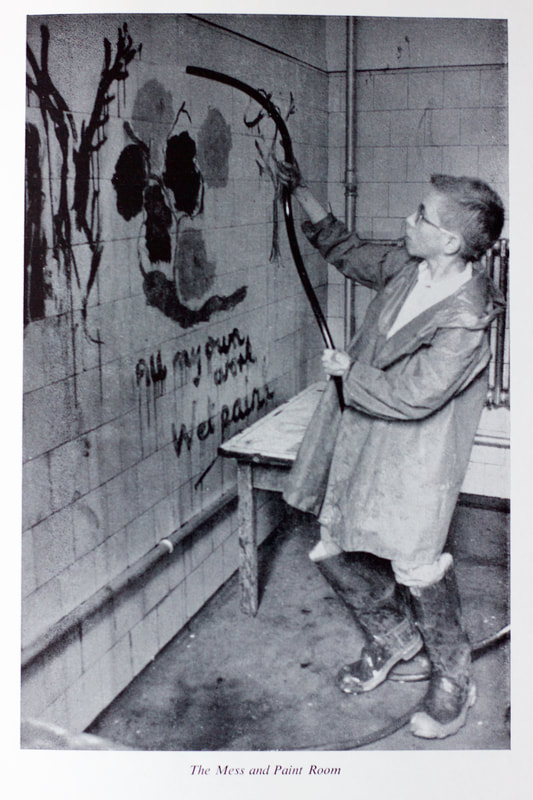

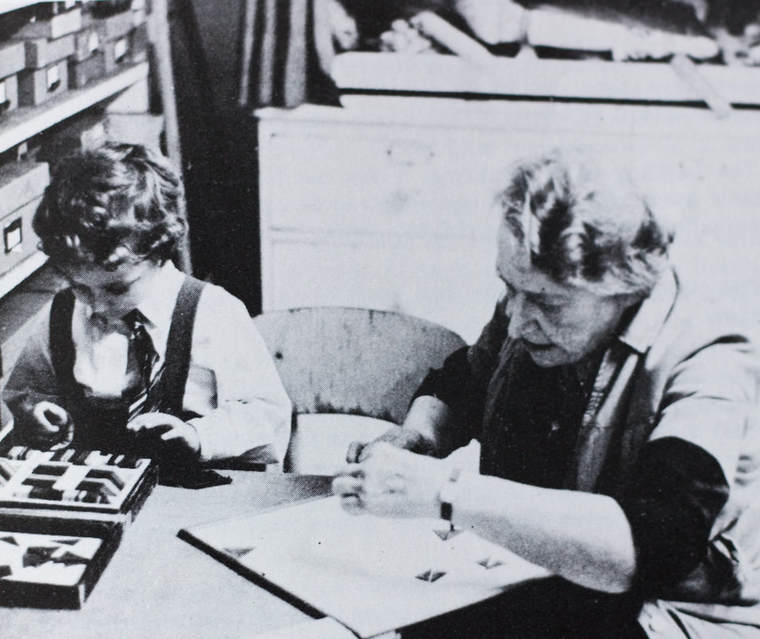

Margaret Lowenfeld (1890-1973) was a pioneer of child psychology and play therapy. She was able to make creative connections of the highest originality. The child-centred philosophy she developed and its process of therapeutic play-making was the culmination of many factors: central to these being her experience of children traumatised by World War One; and also her observation of the colourful patterns in Polish folk costumes. Her work and legacy has influenced my thinking and art practice, both before and after the Grenfell Tower fire that occurred on 14th June 2017. I have always used a model of art making that was rooted in play and non-verbal processes of communication. I was able to use this during Art for Silchester, a seven month residency that has just ended at Silchester Estate. I worked with residents and children who live across the road from the tower and each of whom are coping with the tragedy in different ways. During these sessions, we made large scale drawings and ceramics which were indirectly connected with the therapy of Margaret Lowenfeld, who first started her work in this area of North Kensington in the late 1920s. I also recently met up with Margaret Lowenfeld's great nephew, Oliver Wright, who is one of the therapists working with the NHS in providing support to local residents traumatised by the fire. But this blog is an interview with Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock that was recorded from July-Sept 2018. She is retired from practice, but was trained at The Institute of Child Psychology in the early 1970s and was the leading proponent of Lowenfeld Mosaics as applied to child psychotherapy. In talking about her life and work as a Lowenfeld therapist, I was also able to open up and have a reflective space to think about my own feelings, my inability to voice them over the past year and how I am now moving forward as a person and artist. A war child in Hong Kong and China I was born in Hong Kong, a British colony in 1935. My parents were both teachers. When they graduated from university they started their own school based on my mother’s ideas. She was an intuitive teacher and had this notion that when you teach a child it isn’t just the teaching that counts. It is also about the child. In Hong Kong during the 1920s and 30s that was a rather unusual idea. When the Japanese took over Hong Kong they changed all aspects of our lives including our consciousness. When my brother was born, my parents decided they didn’t want to live under the Japanese and they went to Canton, China. We had nothing and squatted in an empty house. My parents had to have two jobs in order to have enough money to feed us. I was left on my own and wandered around quite a bit. I once stumbled across this march. Being small and very inquisitive I wiggled to the front. There were two Chinese men being executed by the Japanese. The whole crowd watching was Chinese. As soon as one of the prisoners stepped forward the crowd cheered. Then a band of soldiers tried to shoot him but he kept on spinning and it took a long time for him to fall. The crowd just kept on cheering. I was an innocent child and didn’t know anything about politics, but I thought: fate was going to show the people this was a good man. Children see things that they don’t understand and they have to make some sense of it. I didn’t see him fall and I thought he was a good man. That thought came to me as a child and I only found a word for it, patriot, when I came to England. So the words come much later in my understanding. After some time my father returned to Hong Kong to see when it would be safe for the family to return; leaving my mother, my baby brother and myself in Canton. It was during that period that I met a Japanese boy. The meeting was very curious because the Japanese boy was trained to think that Chinese natives were bad. I was walking with my brother in my arms and he threw a stone at me. It hit my elbow and I got really angry. I rushed home, dumped my brother on the bed and went back. I said you hit me and I’m going to hit you back. It was very foolish of me because I was eight and very tiny. He was about ten or eleven. He was so shocked because I could speak Japanese. He then said: if you can speak Japanese, you must be educated and civilised. So he wouldn’t fight me. We became friends and I learnt even more Japanese from him because I didn’t have anyone else to play with. My mother knew nothing about this Japanese boy because she was so busy earning our rice. Just meeting him prevented me from thinking that all Japanese were bad. This later fed into my understanding that all group prejudices were a generalisation of personal experiences. Life is not simple. It’s not reasonable. It is not governed by things like - if this happened here, then that happens there. There is a war, but for the individual child all kinds of experiences are possible. These were war-time relationships and had no consequence afterwards. But even now, I sometimes wonder what happened to that Japanese boy. A scrambled education and life in post-war England We came back to Hong Kong in about 1946 with a wheeled cart and the little luggage we had. My father had found a flat. I continued to look after my brother but not for long. My mother wanted me to go to school, but I had missed three years and so my Chinese wasn’t up to standard. So she decided to put me into a school where the teaching was in English. I didn't know any English. I was 11 and had to spend the first few months writing nothing but lines: I MUST HAND IN MY HOMEWORK. I was always semi-bottom of the class. In my school leaving year, I failed in everything because I couldn’t be bothered to study. It just seemed too difficult. My mother asked me if I would be happy to be a street sweeper or a secretary. It was then that I realised the value of an education that enabled the individual to have a wider choice in adult life. So that year I started to study. When the exam results came out they would be published in newspapers and the top 50 students would get scholarships. I got one. That was such a shock. I later discovered that my mother had been saving money for my education. But my father would always say - don’t overeducate your daughter because she won’t get a husband. You can see there were two very different philosophies in the household. But in the end he was very proud of me. At university I knew I had to study hard. I studied political philosophy. I did psychology, I did logic. All the kinds of things you don’t get at school. Wonderful. I was just enjoying my life. I wanted to become a librarian because I love books. The only post-graduate course on librarianship in the whole of the UK was at University College, London. They had lots of foreign students but they only accepted people with First or Upper Second Class honours degrees. I was very lucky to get in. They said do you have a classical language? I was very cheeky and said I have Chinese. I didn’t tell them that I only studied basic Chinese. They said, they didn’t have a Chinese student and we’ll take you even if you haven’t got any Latin or Greek, nor German or French. This must have been in 1958 and it was a one year intensive course. During the second term I had pneumonia. I was staying in a university hostel and the registrar who was looking after me thankfully had a nursing background. When I went to take the exam, there was no way I could pass it. I passed one paper. I failed the other. They said we really want you to pass, so come back. But I had no money and the course was teaching you how to catalogue Latin manuscripts for working in a university library. It was not for public libraries. I thought this is all too alien and that I couldn’t continue. Domestic life and the discovery of a vocation I then thought I might enjoy teaching but got married and had children. I had to learn how to be a housewife and mother in England. All without any help. What I discovered was that I could talk to another PHD person but I didn’t have any ordinary language. My husband was working in the Midlands as a salesman and he travelled all over the place. We were living in a new estate which had just been built and I didn’t know anybody there. The biggest town was Bromsgrove and that was at least three miles away. We had no telephone. My husband just thought: this is your domestic scene and he decided to have a mistress. I said, this isn’t right, is it? We can’t carry on together when there’s no connection. So I was in a terrible bind and came back down to London. Then he followed with the children. I had to get a job. As I was the one who left, I had to help with the family finances and earn enough so that my husband could have some of my earnings as well. Then I met Jasper. We discovered that maybe we should get together. Jasper and I were married for 46 years and the children lived with us. The children have always thought of him as their dad. During this period I also had personal therapy. The therapist said to me: I can see that you don’t want to be a librarian anymore or a teacher. Do you have any ideas? I said: yes, I want to sit in that chair (pointing at her). I’m going to be a therapist who sees children. First Mosaic made by Therese upon arrival at the ICP, 1969 The Institute of Child Psychology (ICP) I went to Hampstead to visit the Tavistock Clinic. They said you can’t see anybody because they are seeing children and they are in private practice. I said: how do I find out about your training? Well, you’ve got to come to attend our courses. How long will this take? The lady said: it depends on the individual but it could be 4 or 5 years and the student would need to have personal psychoanalysis as part of the training. I just didn’t have the time or money for this. So then I went to visit the Institute of Child Psychology in Notting Hill and they said: Dr Lowenfeld will see you, but she’s with someone else at the moment. They gave me a Mosaic to play with while I was waiting. It was a very clever idea. I knew nothing about what I was doing. It was fun. I made this tree and plane in my Mosaic. In hindsight, I realised this encapsulated my journey and life here in England. The tree was me growing up and the potential to develop in this country through the course. What I didn’t know was that they kept records of all Mosaics and when the Institute closed, I looked through the records and rescued my Mosaic. Margaret Lowenfeld was one of the first child psychiatrists who was interested in finding ways for children to express themselves without only using words. She thought about what happens to a child between age zero and seven. How do children of that age think? She realised that what children perceive is multi-dimensional and cannot be put into words that are in linear time. The child has many ways of seeing the world and they formulate ideas through their sensorial experience. Lowenfeld had this notion that they do it through pictures. So she had this idea of picture thinking in the late 1920s and 30’s and pioneered the use of Mosaics and the World Technique; the latter known more generally as the sand tray used with miniature toys in dry or wet sand. These are play and language tools for the children to express themselves without relying solely on words. Lowenfeld opened the Children's Clinic for the Treatment and Study of Nervous and Difficult Children in North Kensington in 1928. This offered a unique form of therapy for children that did not exist anywhere else in the country. Before the Second World War, the clinic was very well known and mainly supported by private funds. Lowenfeld wasn't charging the local people very much because this was a poor area and she wanted these children to have the use of these facilities. Photographs of Margaret Lowenfeld and children using the World and Mosaic. There was a change of name and The Institute of Child Psychology relocated to 6 Pembridge Villas in Notting Hill Gate. The Institute had facilities that were exclusively given over to the self-generated play activities of children. There was a big basement to the house where the playrooms were located. The children could play ball and use climbing frames. There was a trunk on wheels which the children could hide in. Another trunk had clothes and hats and objects. This was used for dressing up and often lead to dramatic play in innovative ways. There was also a painting room where the children could paint on the walls. You could hose off the paint with water to obliterate the child’s painting should the child not wish for the painting to be kept. There was also a water room where you could have water and toys on the floor and we all had to wear waterproof clothing and wellingtons. The older teenagers might think that playing was too childish and so they could talk in what we called the Quiet Room. Occasionally we would take a Mosaic in for them to use. The Institute always had a file for each child’s therapy work that included a recorded copy of all their Worlds, Mosaics, drawings and paintings. At any given time you might have 6 therapists with their children in the playrooms. We worked together as a team, often helping out by observing other children when the therapist might have missed out on some aspect of their child’s action. It was also a very demanding training. I could write about 12 pages of notes that documented what my child did in any given session. We would never impose a point of view or interpretation of their play. The aim of all this was to allow the child to express their point of view and feelings through play. I started my post graduate course in 1969 and this lasted three years. We only had two new students per year. We had daily supervision, but on Tuesdays and Fridays we had two hours of group supervision to discuss what we called Corporate Cases; these were the children who were not solely the patient of a particular therapist. In the student’s last year, they would be supervised by Lowenfeld. I liked doing the Mosaic and the World with the children. It could take two sessions to do this because sometimes children take forty minutes to do a Mosaic. I prefer to use the Mosaic because they have a progression or a regression and they tend to be linear. I don’t interpret the mosaics. I talk to the children through it and then sometimes they will tell me what it means. The Lowenfeld therapist always had to be lower than the child. I would sit in a chair that is the same size as the child. I’m lucky because I am fairly small anyway. Lowenfeld was not psychoanalytical. She said her ideas were only just one philosophy and so we were taught about Freud, Klein and Jung. She said you will need to understand what other professionals might tell you about the child under consideration. The Institute had a child psychiatrist, an educational psychologist, a social worker and a West Indian social worker, as the area the ICP was in had a lot of West Indians. I think I had an excellent training and it never troubled me that the psychoanalysts thought I was not trained. Lowenfeld had set up a proper postgraduate institution and awarded postgraduate diplomas. They had an academic board who oversaw standards. That’s why I got a student grant because it was properly recognised by the national Education Department. Case studies and sexual abuse I remember this nine or ten year old girl who came to the Institute and just stood rigidly. She believed that her back was made up of one bone and that she couldn’t bend her body. She only spoke in whispers, not wanting to expend her energy reserves. She was worried that she would die and had stopped eating. I said to her: do you know what our back is made up of? She said there’s a bone there. I said your quite right but there’s not just one bone but many bones. I’ll show you. We had these models. I got her the skeleton and I went slowly down the spine guiding her hand so she could feel the knobs. The first treatment objective was to get her to learn about moving freely. We often did body work because, for instance, many girls didn’t understand about menstruation. There was also a fifteen year old Indian girl who was very unhappy and wasn’t eating. She told me she was going to have an arranged marriage but wanted to go to university. The parents felt that any further education would be unnecessary since their aim was for their daughter to get married immediately after leaving school. To enable her to get into university, I said: you have to go to the library rather than home to do your school work. Sometimes therapy is being pragmatic for people to get out of these difficult situations. You’ve got to offer them a solution that will relieve them from that. Only then can it be analysed and if the child wants it to be. What happens if the daughter is expected to sleep with the parents? I said okay. Which side of the bed are you sleeping? I’m sleeping on the right hand side. Who else is in the bed? Mummy is on the other side. So I asked who is in the middle. That’s daddy. I asked her how she liked the arrangement. This is a thirteen year old girl and was a case of sexual abuse. There are girls who I can discover their issues through their World Play or like that girl who did a Mosaic. She kept on shoving Mosaic pieces in between other pieces. I said sometimes that happens to older people as well. She nodded. I said: it also happens to girls. What you need to do, to stop this, is to tell an adult. There’s a law that allows me to talk to you about this. I was getting somewhere with one child who was telling me the parents were abusing her. The parents then stopped her coming to see me, saying Mrs Woodcock’s English is so poor that my child can’t understand her. You can’t argue with that. What I said to the girl was: I’m sorry this is your last session because your parents are not happy about you coming. I said: you know what the problem is. You are fifteen and by the time you are sixteen, you can leave home. That was all I could say. Perhaps there are limits to the therapeutic process. Lowenfeld never talked about sexual abuse at all. You would think she never knew about it. But you see nobody was talking about it at the time. The biggest change I saw over these years was actually having abuse recognised and also the legal aspect of myself and social workers having to report it. I thought that helped me to talk to the children. By law, I had to report this and some other professionals were then able to help the child. In Summary I am extremely grateful to have attended the course at the Institute of Child Psychology. It enabled me to help children by using the World Technique and the Lowenfeld Mosaics. When I graduated in 1972, I worked for the NHS and child guidance clinics in Newham, Haringey and Barnet. Both Haringey and Newham were multicultural and deprived areas. I didn’t actually want to work anywhere else. That was a personal choice. I wanted to work with a variety of children including the poorest. I saw my last case in January 1995 having worked as a Lowenfeld therapist for over 20 years. A selection of my work will be housed at the Wellcome Library as part of the Margaret Lowenfeld archive. Expressing the shape and colour of personality: Using Lowenfeld Mosaics in Psychotherapy and Cross-Cultural Research By Therese Mei-Yau Woodcock, Sussex Academic Press, 2006. Photographs and text kindly reproduced: © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library. Postscript Let us end with Margaret Lowenfeld's account of the first day the Clinic opened on Telford Street in 1928. This was in rooms hired from the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre (aka birth control clinic) where Margaret's sister, Helena Wright, worked as the Chief Medical Officer: The two rooms that allowed for the Clinic's work consisted of one opening direct on to the street, which we used as treatment room for the children, and a second room opening out of it. Here records could be made and kept, parents interviewed, biomedical investigations carried out and discussions conveniently held between myself and my colleague. Money was short so the playroom furniture began as one table and three chairs, one of them a fireside chair placed between the diminutive gas fire grate. The play material was kept in the second room and carefully selected for each child who came - it was too precious to be indiscriminately displayed. Later a second table was added for the children to paint on, the first round table remaining in the centre of the room. A scene in which this table figured later won us our crucial friend. The first child who came was the "bad boy" of the neighbourhood, abominated by the shopkeepers. He came by himself and I do not remember seeing his mother. He was defiant and silent but remembering the Polish children, I left a French painting book - these were lovely (good ones being practically unobtainable in England) on the table with water and painting brushes. He seated himself with his back to the centre of the room and studied them. Half an hour later I stood silently in the communicating door watching him. His concentration was intense, he breathed excitedly and - schools being different in those days - I found later this was the first time he had the magic of colour in his hands. Every day the Clinic was open he came, and slowly began to talk. By that time I knew his attendance at school was erratic and all efforts to improve this had been defeated by his silence under questioning. We made a pact together: more regular attendance at school on the days and times the Clinic was not open, and fresh paints and painting books when he came. It was from the school we heard later that a different boy had slowly emerged - complaints against him ceased. One day he brought a young friend with him and we knew we were winning our way in the neighbourhood. Constantine Gras making a mosaic, with from left to right: red beacon, tower from black to green to no colour; myself draped in those colours; and a key, a set of arrows pointing to me, the tower and Thérèsa as witness to the mosaic. "I felt I needed something in addition to the tower and me. I don't know what it is. Maybe it's a signpost trying to direct me or others, but everything is shifting apart again over time. Then I step back and look beyond the tower and me. I want to get a sense of the overall space and how these objects function within that space. Can I possibly create something that is aesthetically or emotionally satisfying? I am trying to make a work of art. I'm not sure if that is right." "Yes. You are an artist. You cannot escape that." "I was hoping that I might, but I don't think so." "You won't be able to escape yourself, will you!" "No. No." At Play In The Ruins: A Lost Generation

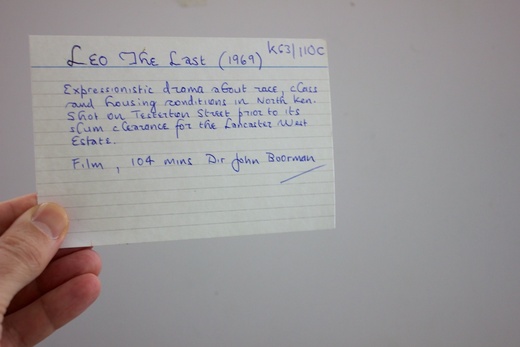

oil pastels, 33x24" 19 Dec 2016 Artist's comments on the reverse of the drawing: Starting off with abstraction, but thoughts turned to Lowenfeld sand play (Sand Face in the picture) and childhood. The news on the following day. The battle and now the desperate evacuation of Aleppo in Syria. One of the defining media images of the year, Osman Daqneesh pulled from the bombed building. His haunting stillness in the midst of horror. Oh no! Everywhere I turn in the archive, I'm haunted by the spectre of Notting Hill - the 1999 movie with Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts. A smash hit rom-com from the last century that still casts a gentrified shadow over North Kensington. I felt compelled to shout from the town hall rooftops that this is wrong or at least needs a corrective. I may be seeking solace in mythic, possibly antediluvian texts, but why is there no archive record of Leo The Last . Well, there is now courtesy of a creative slight of hand.

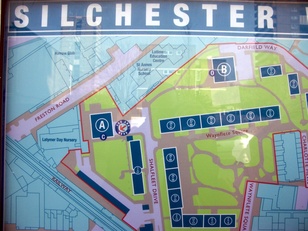

The entrance to the Architecture Gallery at the V&A has a classic marble staircase. It echoes to the sound of history. On the 19th and 20th November 2014, I held a film screening and paper folding workshop here. Visitors approaching the space would have heard the following sounds and voices. Fragment 1 The sound of WW2 bombing, glass shattering and the percussive dub of the Notting Hill Carnival. This reverberation in a usually quiet location caused a few raised eyebrows and the volume had to be scaled down. Fragment 2 North Kensington residents reminiscing about good and bad days, post-war poverty, multicultural experiences, poor housing and the British sense of humour. An American who lives in London and who viewed this section of the film programme commented about the shocking poverty and how in the good U.S. we never had it so bad. Fragment 3 A filmed conversation with Joanna Sutherland, project architect at More West housing development. This is where I am based as V&A Community artist. She talked about: "What we are seeing ... is the threat to communities due to the expense of living, not just in central London, but all areas of London. I think there has been a growing interest in the last ten years, if not longer, of how communities evolve and what's important within a community, whether it's through schools, a community facility, a church. And I hope that this project, Silchester and the wider area, still remains a home for those who have lived there, had children, and maybe they can continue to live in the same place." It was heartening to hear positive comments about this film from residents of the estate currently undergoing transformation. A new community is forming at More West built on the foundations of the previous slum clearance redevelopment in the 1960s. That phase of development was very disruptive coupled as it was with the building of the adjacent Westway A40. It did however create social housing. Today, there is no longer a desire to match that social vision, and what is affordable in terms of rent and quality of life, is beyond the means of many. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and Peabody are providing part social and market housing at More West that consists of 45 rented homes, 39 shared-ownership and 28 for outright sale. The new housing is part of a rapidly changing area. However as our local councillor states: "There are too many poor people." Councillor Judith Blakeman has to deal with many of their social problems. Fragment 4 Glockenspiel and assorted drum kits provide a positive vision of the future. Children from Frinstead House are drawing. A girl illustrates herself waving goodbye to her father from the 20th floor of the high rise; he is waiting for his train at Latimer Road tube station. Another child mischievously draws a giant t-rex attacking the tube station. This is regeneration, disaster monster movie style. Yet another child provides a rainbow arcing across the skyline. This was one of my most direct and rewarding engagements as community artist. I did not advertise this. I merely set up a large sheet of paper in the foyer of Frinstead House and invited local residents to accompany me in filling the blank. Adults and children confirmed their cultural identity and what it means to live in their high rise homes. Fragment 5 - Was not heard at the museum. It has not been caught on camera or in any of my expressionistic documentary work. I hope to render this shortly. Symbolised by a DJ playing at a recent marketing event for More West. He has bought a flat and will move to the area in 2015. He is excited. Young and professional. For him there is no lingering doubts. He is forging the future in progressive sound waves. Zeitgeist. In summary, this curated programme had the aim of dialectical montage, the juxtaposition of contrasting images and sounds. This is our experience in all its complicated social modes. It is both beautiful and ugly. We build for the future and paper over the cracks. Speaking of paper (workshop), I have also provided a visual record of how young and old came together at the V&A Museum. Complete strangers who with a little encouragement and artistic structure are able to express light and shade, twisting new shapes into being and creating another fragment (like no 4 above) that brings a smile to my face. No Object My studio is a 1966 council flat that has no domestic furnishings. I invited visitors to bring an object from home and to tell me a story. Many thanks to visitors and participants in No Object. You brought my studio to life for a day with your stories about a milk and marmalade pot, harmonica, Big Ted, Aboriginal art and 8mm projector. Together we made the film, No Object. Event comments Nahid, Silchester estate resident: "Amazing insight to the area I've been living in for over 30 years." Neil Hobbs: "What a wonderful project. I hope this is happening all over London. If not, why not? This social history is so very important and should be recorded." Lucilla Nitto, photographer and W10 resident: "Very interesting mix of space and art. Well done!" No Object was held as part of the Portobello Film Festival and consisted of:

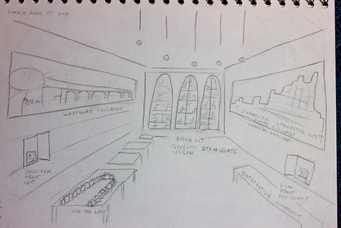

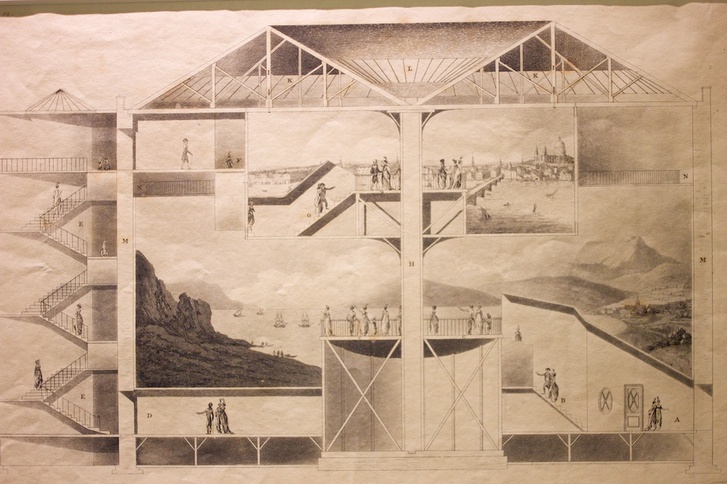

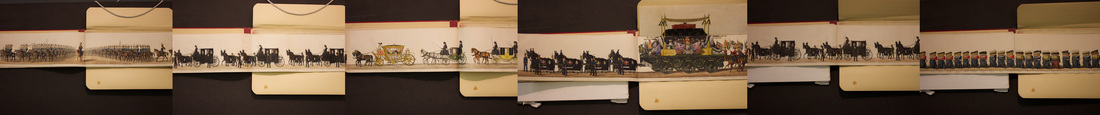

Exhibition notes The gritty streets and houses of North Kensington have attracted film makers since the 1950s. In The Blue Lamp (1950) a classic cops and robbers car chase along Ladbroke Grove ends with a car crash near Latimer Road. In the following year, Ealing Studios, provided a neat comic variation to the chase. In The Lavender Hill Mob, two police cars crash at the juncture of Bramley Road and Latimer Road outside the Bramley Arms. Their car radio antenna become entwined. The resulting incongruous broadcast of “Old Macdonald had a farm and on this farm he had a pig” resonates deeply with the history of the area, noted for its pig farming in the 19th century. This part of the Hill is known locally as Notting Barns or Dale. It consolidated its seedy reputation as a “slum” with four days of race riots in 1958. Ethnic tension would feature in Sapphire (1959) with a scene directly culled from press accounts of the riots. A black suspect is chased by the law from a club in Shepherds Bush and is assaulted by Teddy Boys in Notting Dale. He is saved by the actions of a local grocer woman. Fact made fiction. The race riots provided a poetic framework for the book Absolute Beginners (1959) written by Colin MacInnes. In this seminal novel about the youth culture of the day, the writer had this to say about the area: “A long, lean road called Latimer road which I particularly want you to remember, because out of this road, like horrible tits dangling from a lean old sow, there hang a whole festoon of what I think must really be the sinisterest highways in our city, well, just listen to their names: Blechynden, Silchester, Walmer, Testerton and Bramley..........and there’s only one thing to do with them, absolutely one, which is to pull them down till not a one’s left standing up.” This was a prophetic statement as the houses and streets were all torn down for the building of the Westway (A40) and council estates in the 1960s. A musical adaption of Absolute Beginners was made in 1986 featuring David Bowie. Kitchen sink dramas of the 1960s would also tap into the poverty and housing inequalities of the area. When Bette Davis visits run down Walmer Road in the 1965 film Nanny, she discovers her estranged daughter is dead. A result of a back street abortion gone horribly wrong. This pushes her character over the gothic edge. Far more sinister happenings would take place at nearby 10 Rillington Place. John Christie, the serial killer, would offer deadly medical assistance to vulnerable women. The late Richard Attenborough powerfully conveyed Christie in the 1971 film version of the case. With the building of the Westway and the estates, new possibilities for filming road sequences would appear. When Hammer made The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1972), it seemed fitting that they should use the redeveloped Bard Road, just off Freston Road (formerly Latimer Road). This was and is a dead end road behind the Harrow Club. In the film, two biking Hells Angels trail a secret service woman and kidnap her at this point of no return. Radio On (1979) came out of left field. A black and white film about alienation and featuring the modern existential drive. Not at street level, but above on the turbo charged Westway. Adulthood made in 2008 by a new class of film maker, Noel Clarke, captures all the angst of life on an imaginary estate. The culture of young people who are trapped in the vicious cycle of gang crime. The police from The Blue Lamp are nowhere to be trusted or respected. The bad guys are the good guys you root for. The film uses locations in North Kensington that could be located in Silchester or Lancaster West Estate; these stand on either side of Bramley Road and Latimer Tube Station. This council flat at 7 Shalfleet Drive is part of the 40 year old Silchester estate. It will be demolished in January 2015 to make way for mixed-tenure housing. As resident artist based here, I will be making a film project about the new housing development and the new community that is forming here. Looking to the future, I wonder what films will be made in this area over the next 50 years. Will they replay good cops, bad cops? Will poverty and housing issues still feature? Will more diverse multi-cultural voices be heard? Will there be estates dominated by a new middle-class criminal? Will the narrative film form, the staple of generations, become obsolete in the new social media age? Leo The Last art project Leo The Last is the definitive local film that resonates with the themes of my residency: housing, architecture, film. Leo The Last was directed by John Boorman in 1969, between his Hollywood films, Point Blank and Deliverance. The story concerns a European aristocratic landlord who moves into a slum area of Notting Hill and becomes radicalised by his oppressed West Indian residents. The film is an experimental adaption of a stage play and Boorman chose the location because of family links with the area. Uniquely, the design team were able to use a local road, Testerton Street, prior to its regeneration into the Lancaster West Estate. Nearly all of the residents had been moved out and Boorman was able to paint all the houses and road black. This created the unique monochrome colour palette in the film. A false house was built across Testerton Street. This was the stuccoed white house for the central character. In the archive, I came across the touching story of one couple, still living on the road at No 27 and waiting to be rehoused. Arthur and Grace Clark refused the offer of £50 to have their terrace house sprayed black. “We could do with the money really,” said Mrs Clark, who had lived all her life in the house. “But if we agreed to let them paint our house, the vandals would get busy, as they would think it’s empty.” I am working with the V&A Museum to screen the film for residents at Silchester and Lancaster West Estate. They will then help me to make a ceramic installation based on images from the film. It might not be the final frontier. But this blog entry begins and ends with space. The big bang of the widescreen, large format and panoramic. A location for an artist to perform and connect with people. The contested politics of space, building homes and forging communities. First stop. Let me beam you to my non residential artist's studio. All artists cry and bleed for a space. This is nothing new. East London currently rules the roost, but in the past artists would look to this stretch, west of London, for verdant grass and fresh air. William Mulready was one of the first artists to settle in Kensington in the first decade of the 19th century. He shared digs with fellow artist John Linnell at Kensington Gravel Pits and then had a studio house built for him in 1827 at Linden Grove (now gardens, the house is no longer extant). This was during the first wave of development for the Ladbroke Estate and Mulready lived here for the remainder of his life. Nearly forty years later, Nathaniel Westlake, having just converted to catholicism, has his architect friend, John Francis Bentley, design a house for him in Notting Barns. Westlake did not stay here for long. We can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. His house is still standing and looks out of place next to the Lancaster West Estate. Mulready and Westlake are both closely associated with the birth of the V&A Museum and have work on display. In terms of art, studio space and the V&A, I am following in their footsteps; more of this anon. During my V&A Community Artist residency, I have that precious commodity for an artist, studio space. I am not based at the museum like the other resident artists. I am a tenant of a flat whose rooms can be sculpted, wallpapered, improvised. It's an in-between space, a former council property, that will become part of a mixed tenure housing. No one will care if I artistically trash it as demolition is due next year. I'm conscious of being the last in line. Leo The Last. The last house demolished. I've explored these in previous art projects. Now. I'm living out my very own kitchen sink drama. What about the medium or mixed media of space? Artists are always grappling with this technical consideration, whether it's processing on a computer or via more traditional craft techniques. I usually compose an image through a viewfinder of a camera or a sketchbook often leading to 16x20 inch drawings; this is a legacy of working with photo paper formats in a darkroom. There are also multiple dimensions to my residency: how art relates to community and housing and architecture. As I want to share and encourage others to participant in these processes, I need to think big as in large scale. This is new to me and will present its own set of challenges. I also need to engage with my immediate neighbours on the street, residents in the estate, people in the ward, across the borough. An audience that might not understand "art" or perhaps even know who the V&A are. As I begin, so I end. Everything is hurtling towards a date in January or February 2015 with an end of residency event at the V&A. This is in the lunch room for visitors to the learning centre. However being the V&A it is no ordinary lunch room. It has a cinematic sweep, certainly from the top down. Even wall lined cupboards gets one thinking of spaces within space. I'm looking at constructing panoramic displays here, perhaps of the Silchester and Lancaster West Estate and its residents. This will include film of the new housing development taking place and the new community that is forming. Also perhaps a representation of the Westway (A40), a built structure that dominates this area of North Kensington. Can I also chuck in some "stain-glass" imagery for the aesthetic thrill? On August 18th I hosted an open day bringing some of these issues into focus. I did wonder how many people I could safely fit into the studio flat and its 4 spaces (20 comfortably at peak capacity). It was a good idea to convert a large store room into a history room with archive maps and images. In total, I had 60 plus visitors. Delighted to see my neighbours on Shalfleet Drive popping in to see what all the fuss was about. This is important as I plan on working with them on a film project. There was a group visit from Open Age who took to my live drawing like ducks to water. Great to see old colleagues, including Adam Ritchie who was pivotal in establishing the community ethos for the Westway and the building of play spaces for children in the 1960s. The Mayor of RBKC Maighread Condon-Simmonds also paid a visit. She is a charming lady, really down to earth and digs the complex layered history of this area. In her thank you letter, she chimed in with my thoughts about the challenges of space: "You have made a truly interesting display in such a small space.....The north of the borough has so much more space than the south and it is good to see the new developments with good quality homes." For the exhibition, I also created a drawing installation called House with 40 Rooms. In each room there was an object. These objects were all from the V&A. I invited participants to use words or images in response to the objects in the rooms. Local resident, Maggie Tyler, wrote the following about her drawing: "I used to look out at a Stag's Horn tree and a round window in the wall of the house at the end of the garden. At night, I would see the silhouette of the foxes walking along the top of the wall past the round window. Then! The Neighbour moved out and the new neighbour built an extension. A modern extension that covered and destroyed the round window. The tree fell down and the view has changed. I now look at a modern box!" A few days later, I opened my studio during the rain-sodden Notting hill carnival. Sheltering outside my flat, I took pity on a group of performers and invited them in. Amos has been taking part in the carnival for over 15 years and we chatted about its history which is reflected in art work on display. New residents moving into More West from 2015 (once the flat is demolished and new housing built) will find they are on the western edge of the processional route. There is intense debate about the future of the carnival. Is it too big for the streets of Notting Hill? Cllr. Eve Allison, who has ancestral roots in the Carribean, believes there are compelling reasons for relocating the carnival to a larger green space. This would be a tremendous loss to the area and signal a departure that the carnival has lost its community connection. Down at the V&A, I've been reflecting on this and artistic precedents for panoramic art. Nathaniel Weslake has large upright stain glass and oil paintings (with associated mosaic) on display. I've previously commented on his smashing stain glass. This time I'm checking out his contribution to the Valhalla portraits. It seems apt that Westlake should choose as his artistic role model, Fra Beato Giacomo da Ulma (d.1517), a Dominican Friar who painted on glass at Bologna and is an obscure figure in the series. As Westlake did for da Ulma, I will likewise do for Westlake. Celebrate the art and allow this to percolate into my practice. This means moving into unfamiliar territory, but I'm up for the challenge. I can start digitally with photoshop and a literal following in the footsteps (see image below!) This is a simple tool to collage ideas and feelings about the construction of a pictorial landscape. Just the first step in a process of ongoing experimentation that will probably morph into craft and film. In the prints and study room, I perused an 1801 plan for a panorama in Leicester Square. This was presented as various walking and viewing points in a space shaped by architect and painter. Ingenious. I also marvelled at the skill employed in a fold-out book made to commemorate the Funeral Procession of the Duke of Wellington in 1852. It was made by Samuel Henry Alken and George Augustus Sala. The pomp and circumstance of this stately occasion made an interesting contrast to the recent carnival floats that passed by my studio. It connects with previous thoughts about creating work that fuses the historic with the contemporary. My art musing is only of interest when it translates into practical application. How to use art to look at the urban environment, the community spaces around my studio and the homes that residents have made here? How high rise residents perceive the new developments taking place below them? How residents in the shadow of taller structures respond to changes in light and air quality as the sun climbs and then dips into the West? How do I create a space for public participation in the process of making art? How will others want to comment on the world around them? I need to bear in mind that this might not necessarily tally with how I view the world. How will art be elegantly displayed for a follow-up activity of engagement? Can I bring this all together at the V&A lunch room as food for thought? I don't particularly want to end on a question, so offer this as a postscript.

I'm being managed by Laura Southall in the Learning Department and it was great to meet more of the team. I set them a 10 minute challenge to make some sculptural forms and showed them a few examples. If they ended up making a posh version of a paper aeroplane, that would be fine. Dah! They do all work for the V&A, pre-eminent design and art museum. Fold, tear and sellotape. Horizons west. Feels good. This is my first visit to St Peter's Notting Hill and the church is sheer stone delight. It was designed by architect, Thomas Allom and built in 1855-57 at the same time as he engineered the layout of the surrounding Ladbroke Estate. This is the classic image of Notting Hill; terraces of stuccoed brick houses that back onto private garden squares. It is not a million miles away from the "grungy" edges of North Kensington that I usually inhabit. This is a research trip in preparation for my forthcoming community artist residency and trying to locate new regeneration schemes in relation to the history of architecture and urban development.

The past can come back to haunt us. As we speak, Thomas Allom must be kicking in his grave at Kensal Green cemetery. An architect and building contractor recently pleaded guilty in court to causing irreversible damage to a Grade II listed house designed by Allom. This is just around the corner from the church at 18 Kensington Park Gardens. The interior of the property was gutted with the loss of period plasterwork, floorboards and fireplaces. The house is currently being restored by another firm. On more hallowed ground, there is a lovely exhibition currently at St Peter's called Polarities. It features the work of Edward Allington, Asaki Khan (featured in photo), Katherine Lubar and Terry Jones (also photographed). I had fun attempting to "row" Terry's sculptural boat. Taking shoes and socks off, I meditated and walked across the installation of salt and sand created by Asaki. How do these artists conceive of polarities in relation to their art? "The idea of contrast has always been an influence on the practice of the artists in this show. There are many opposing elements that can be read into the work: hot and cold, light and shadow, negative and positive, and of course, the metaphysical: light and dark - good and bad - which bears special relevance to this particular space." Only now showing on the 16th and 17th May from 1-5pm. Well worth catching before it closes. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed