|

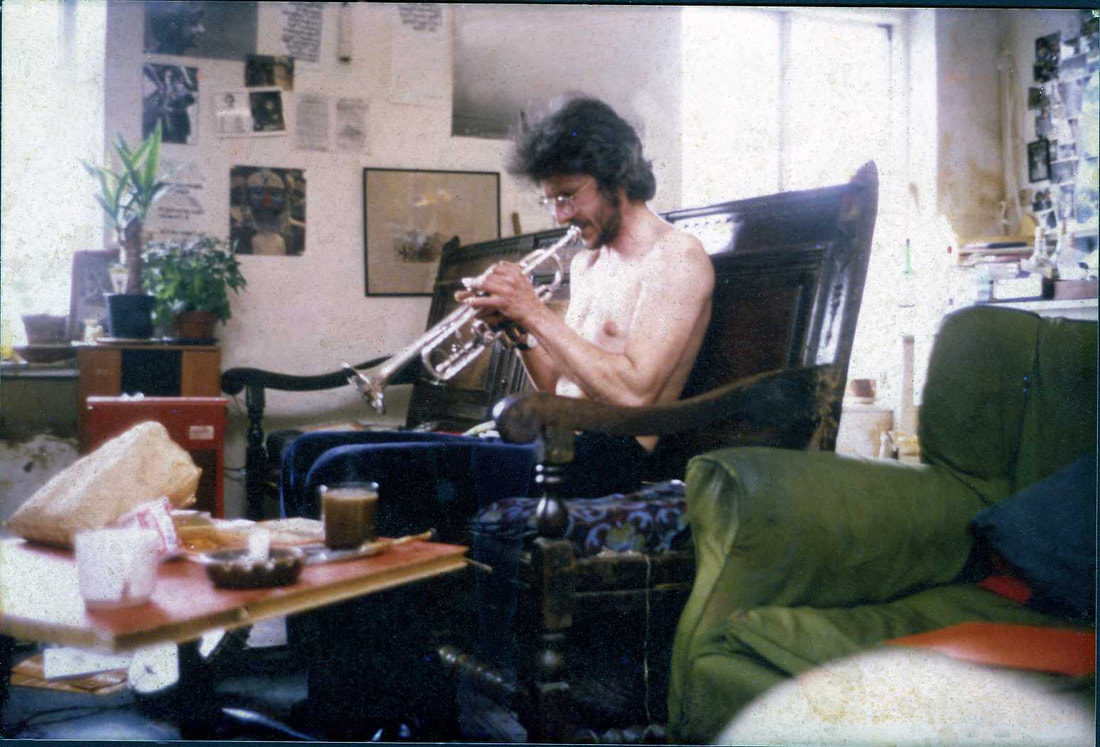

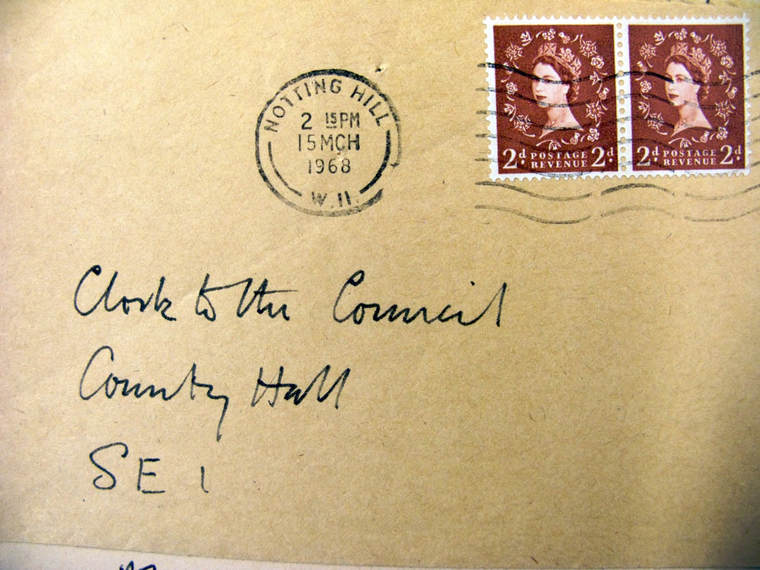

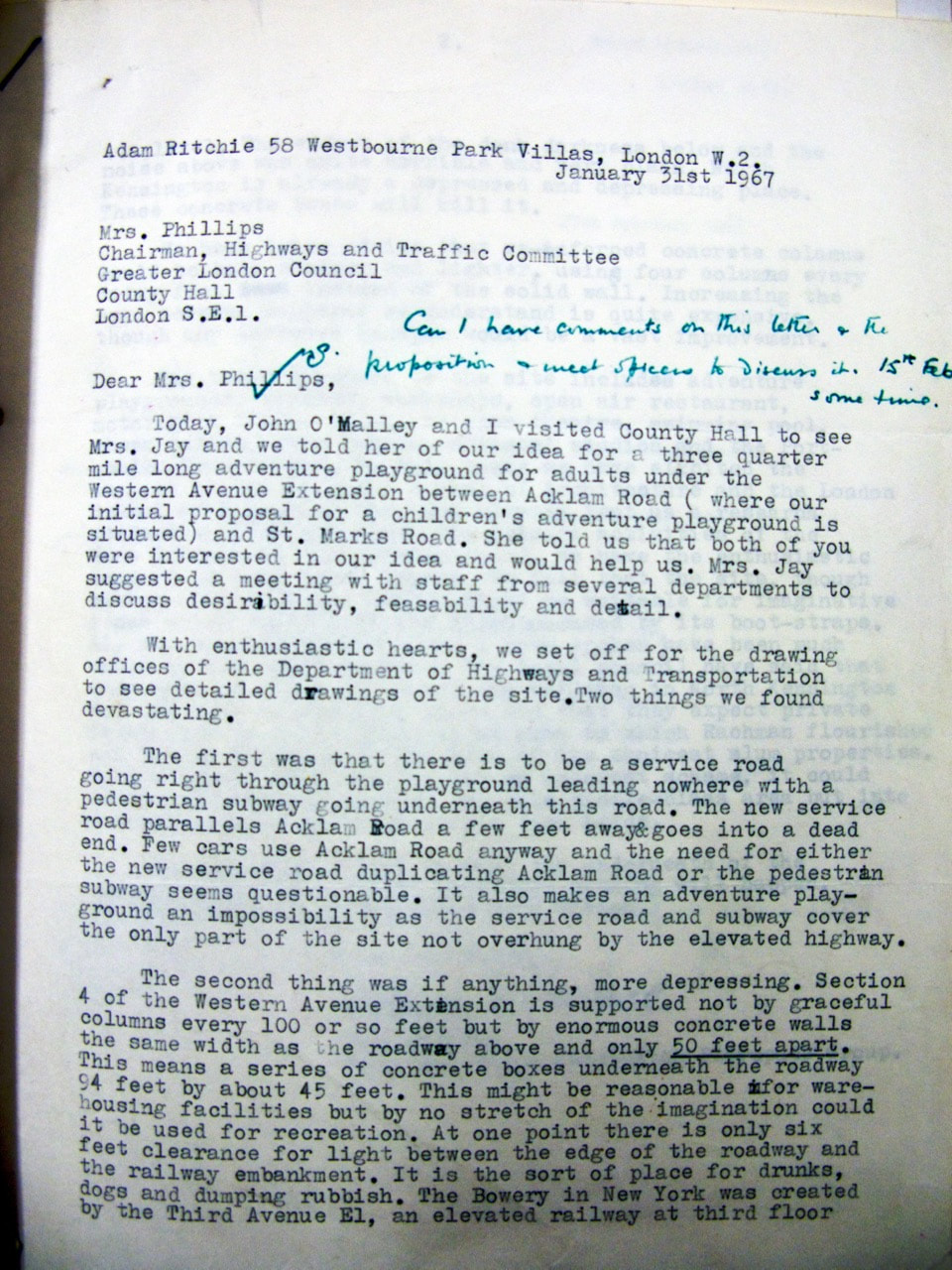

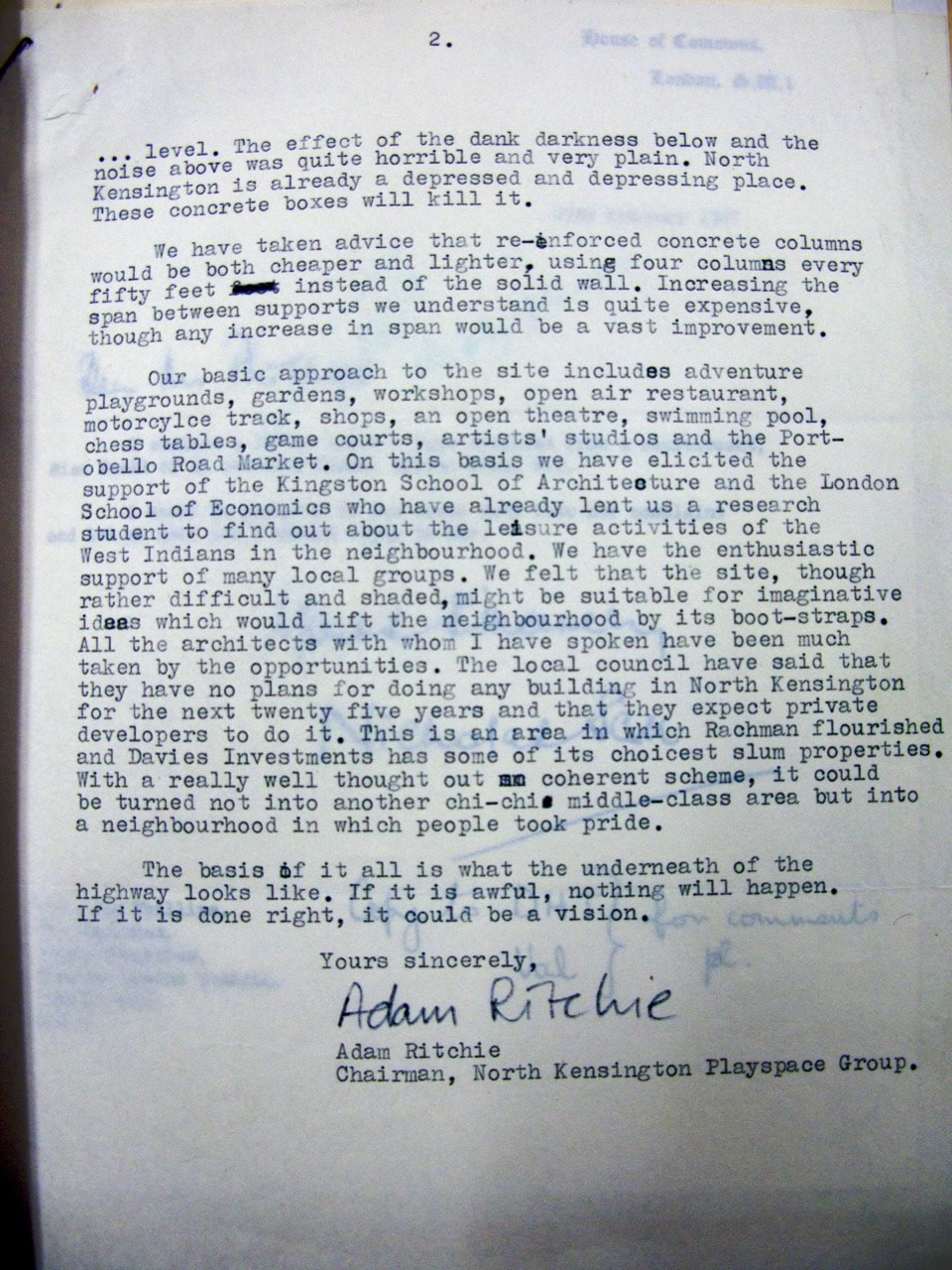

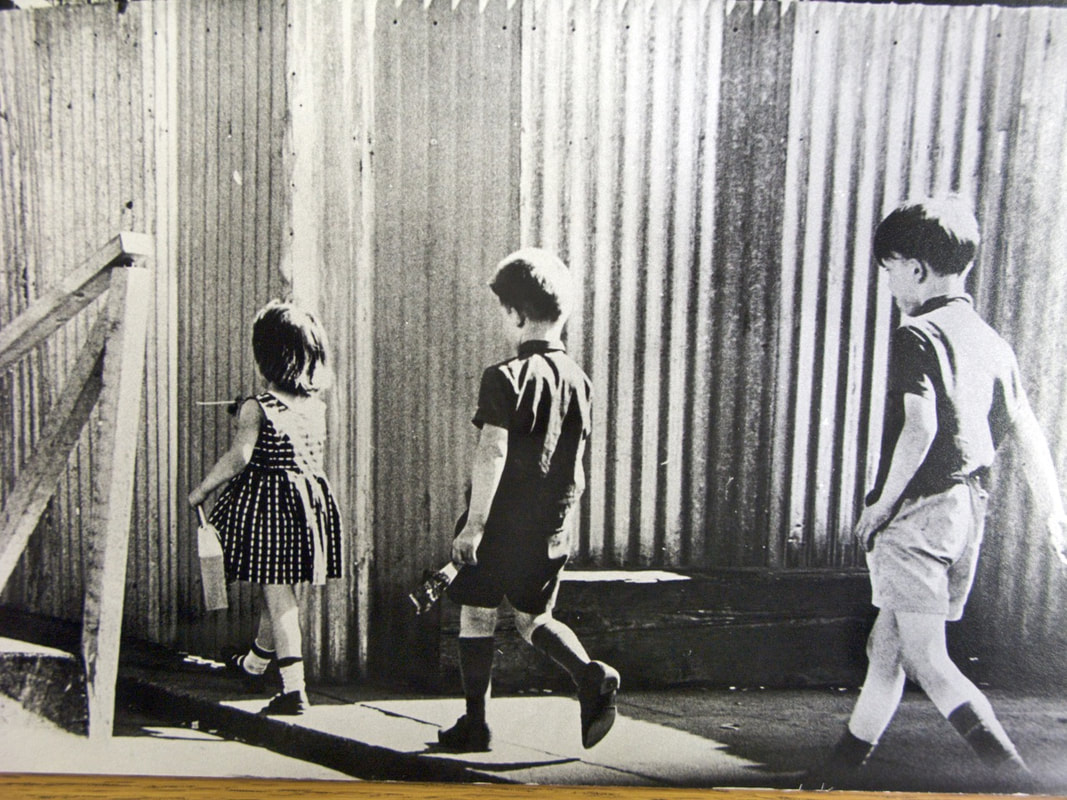

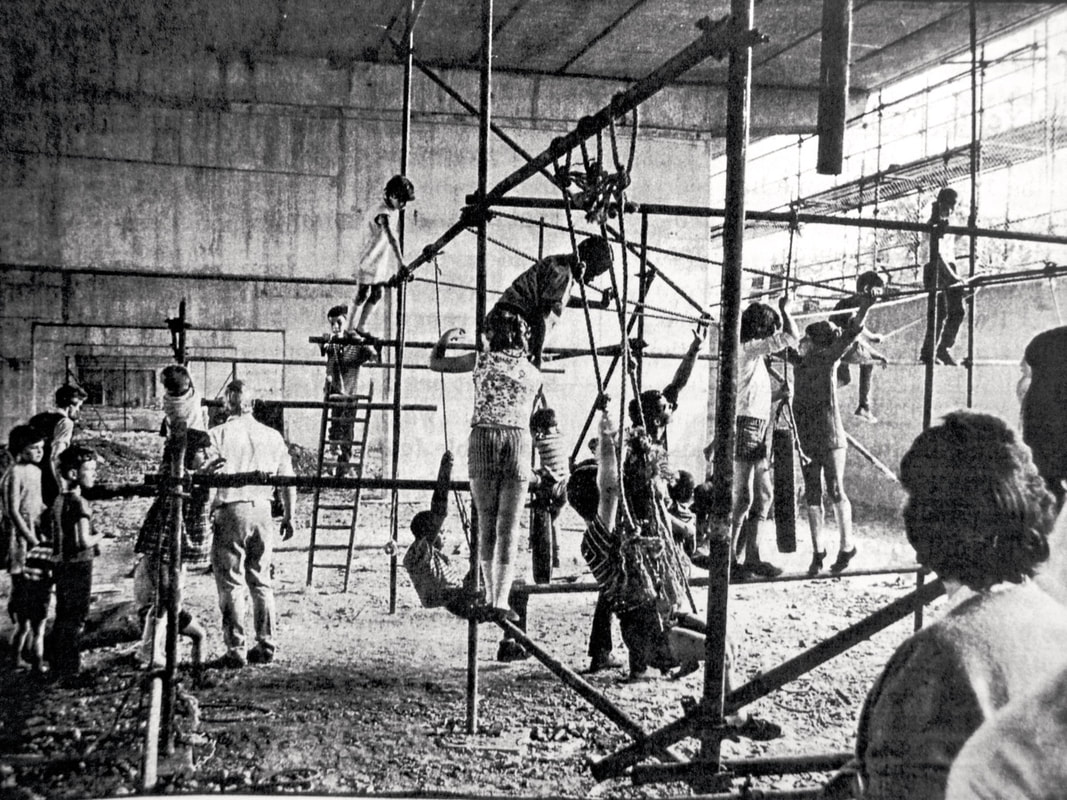

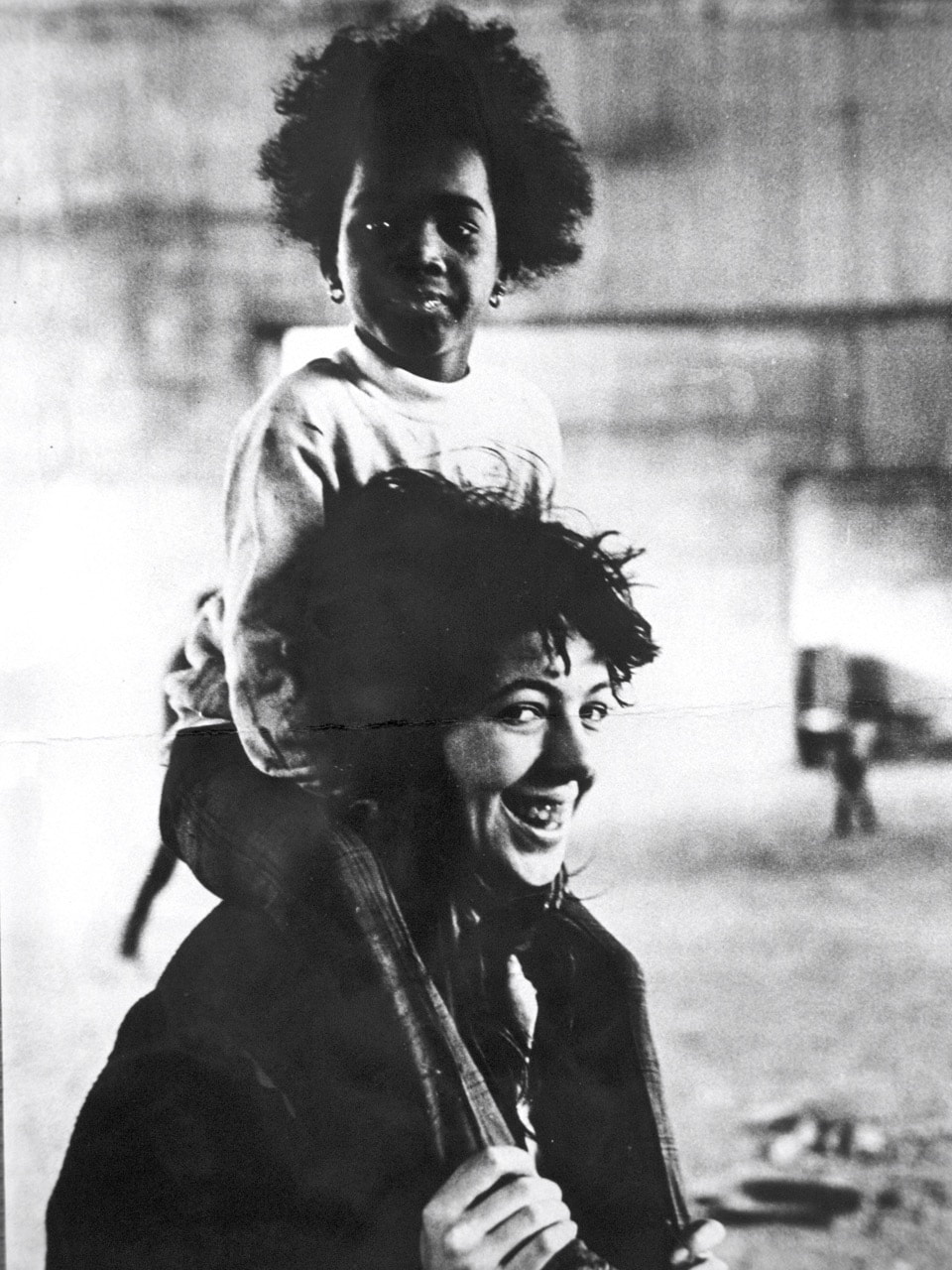

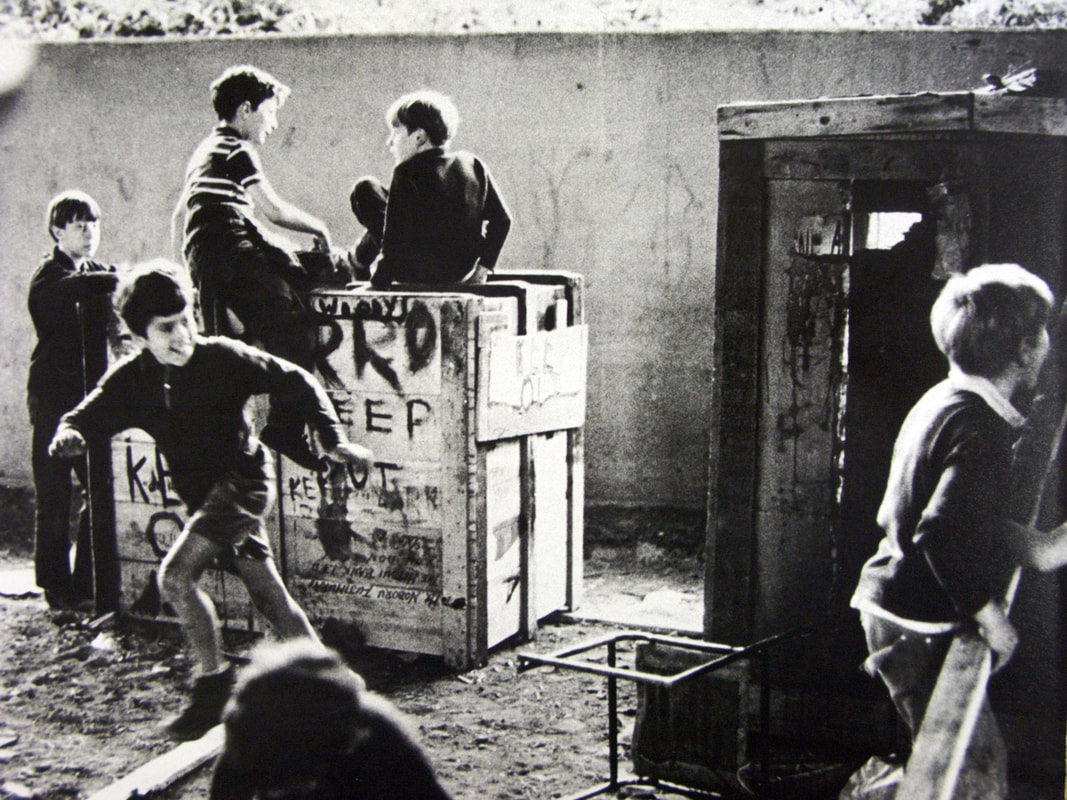

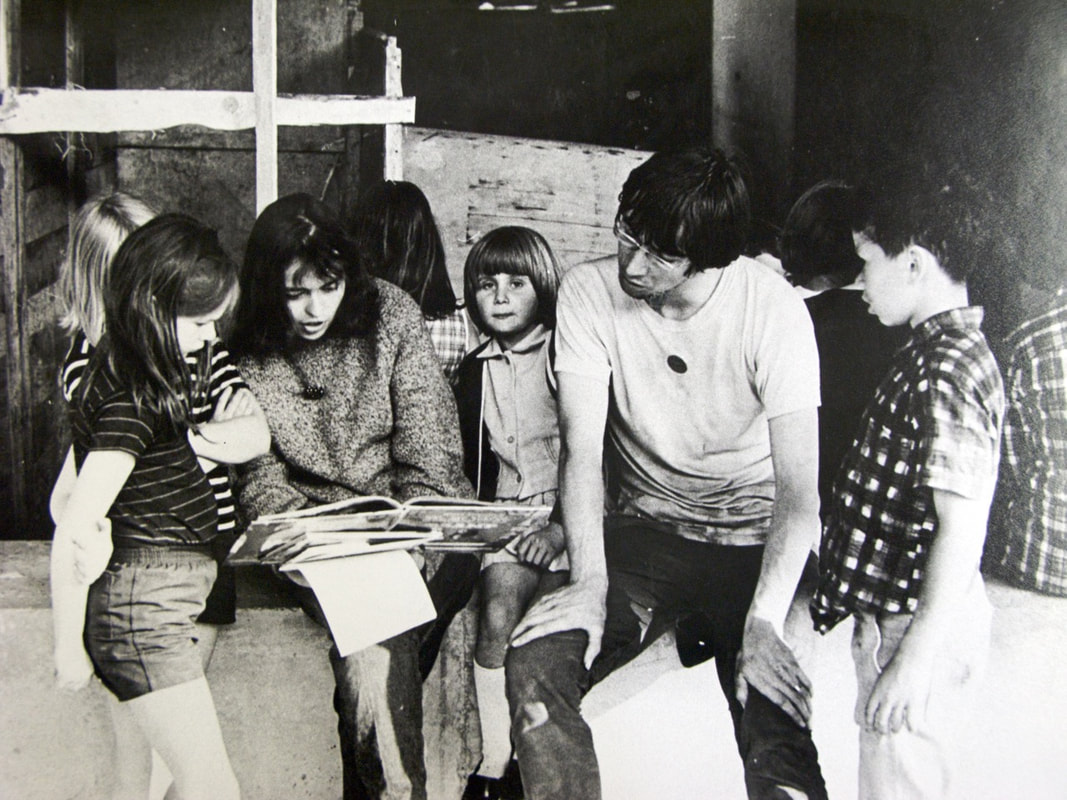

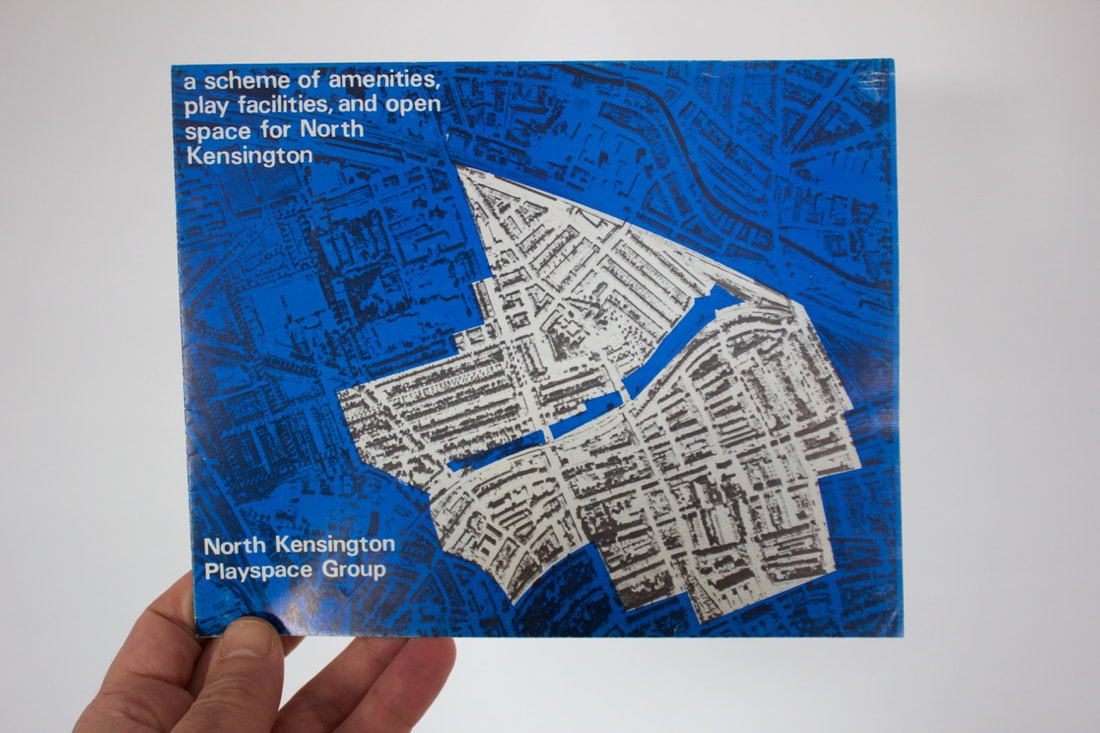

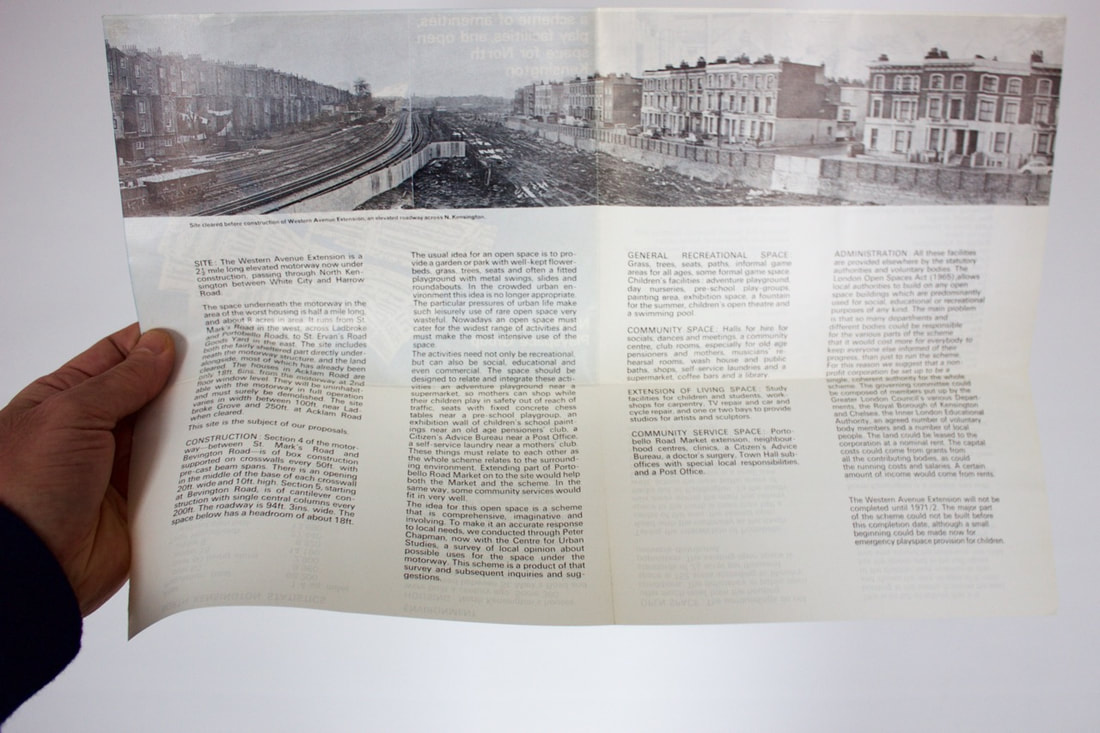

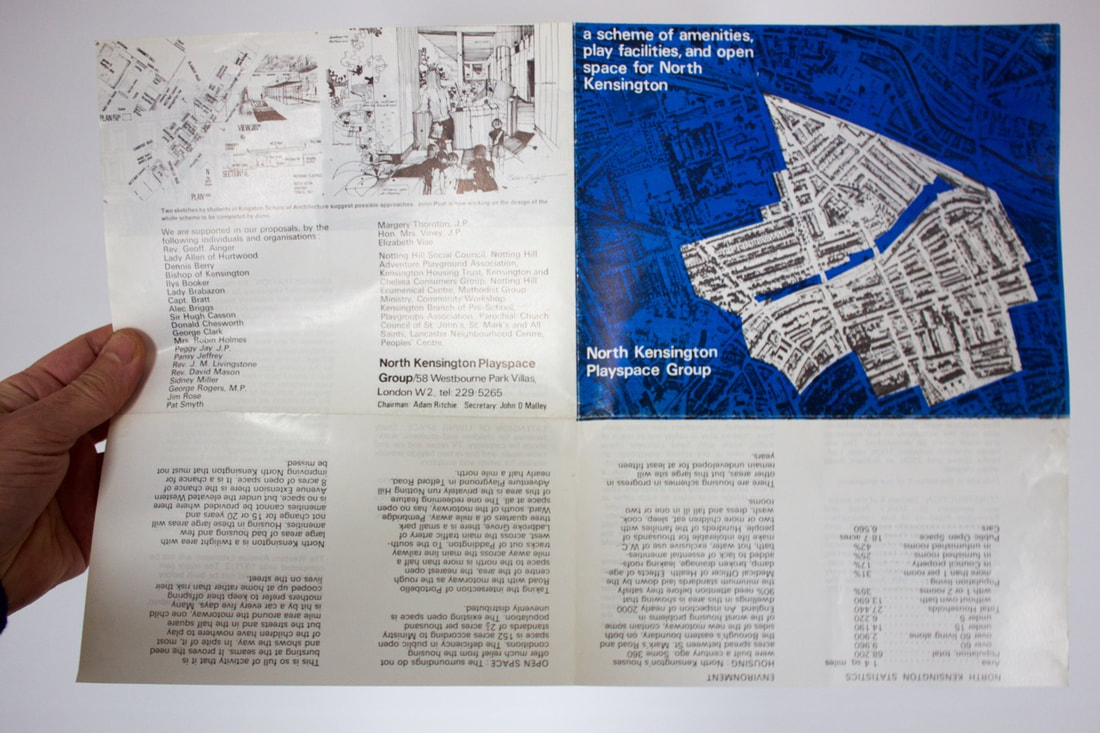

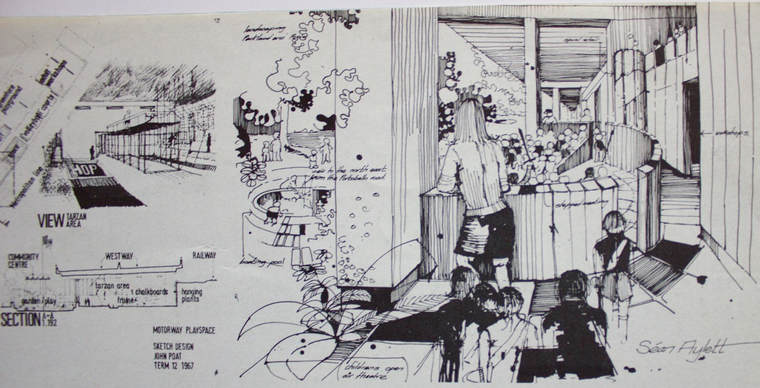

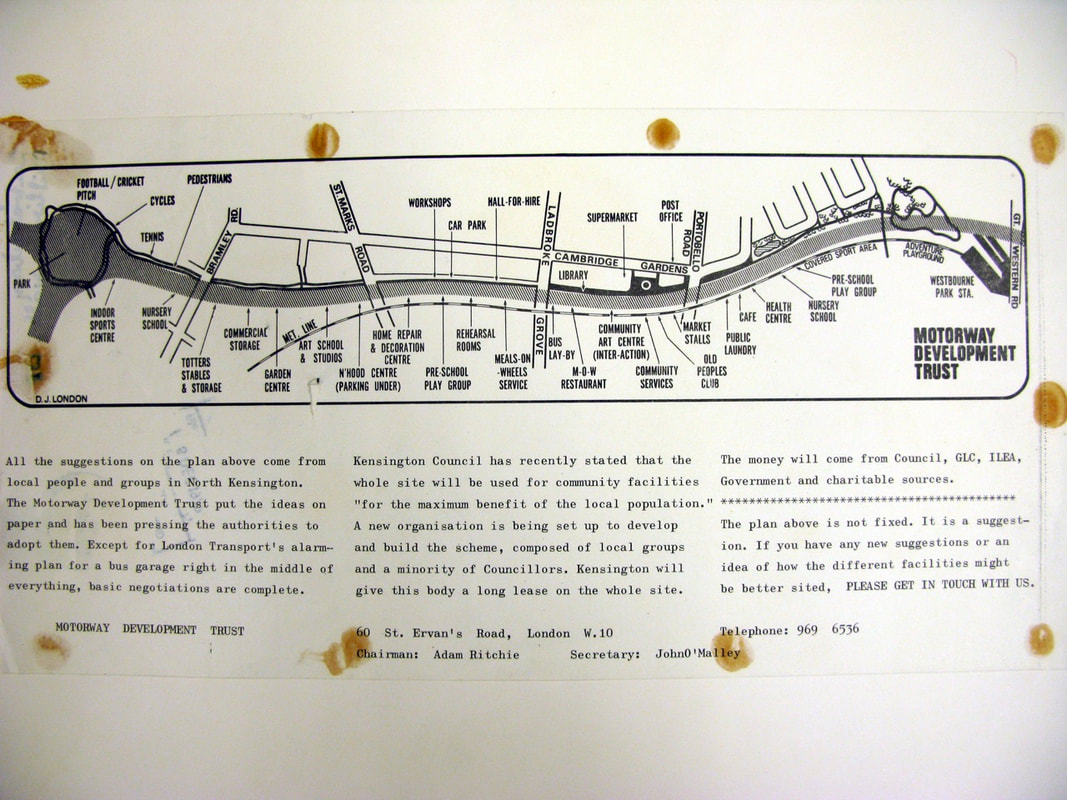

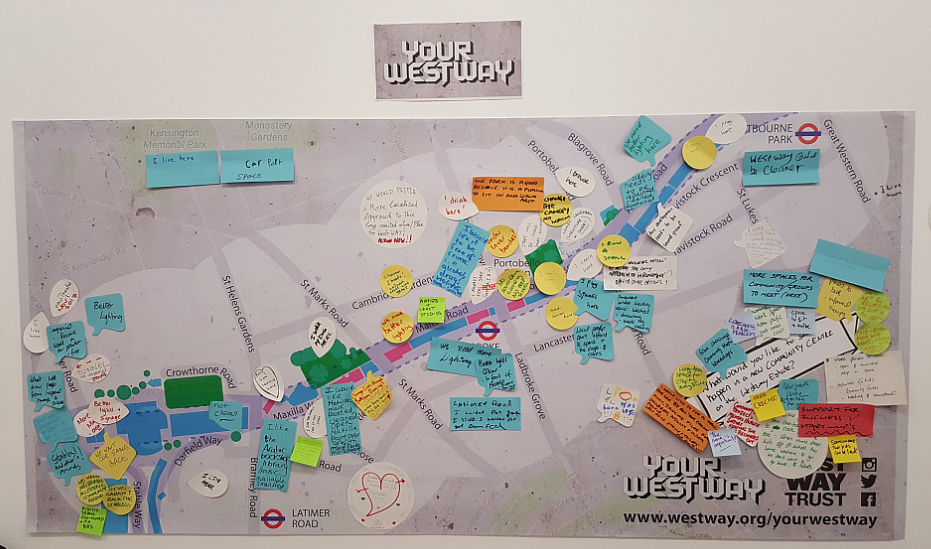

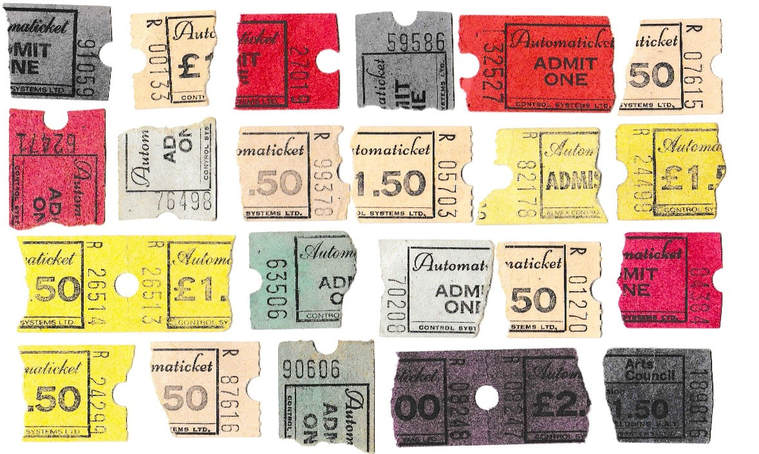

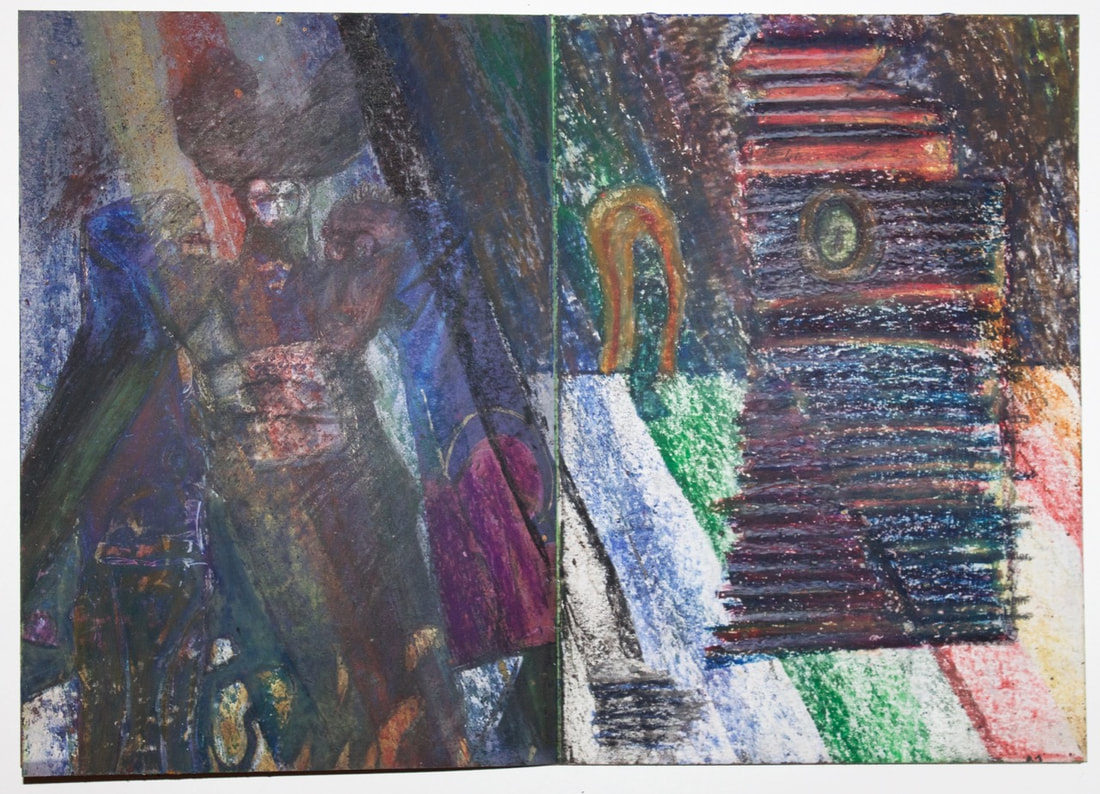

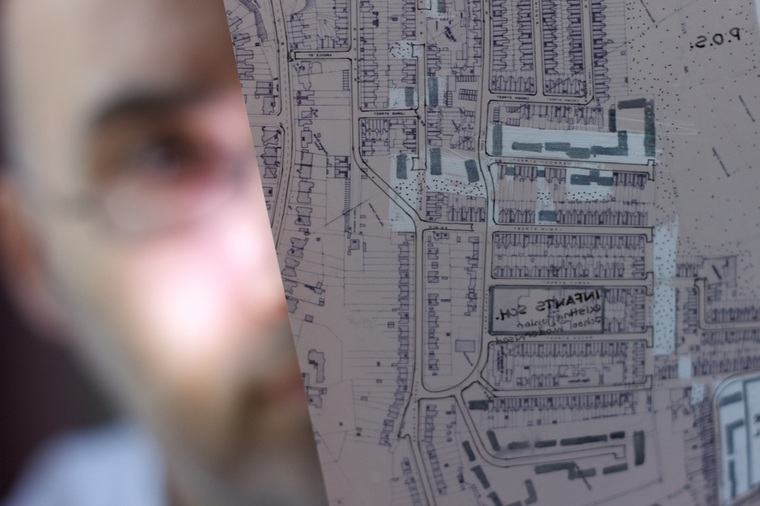

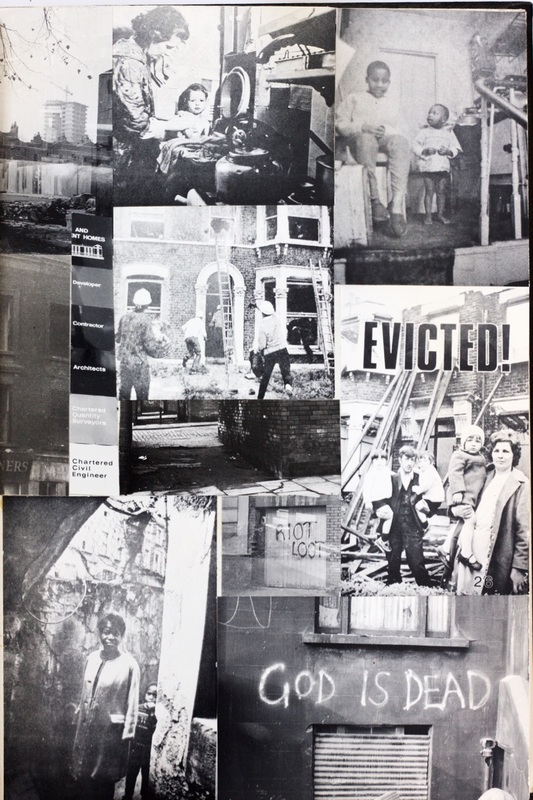

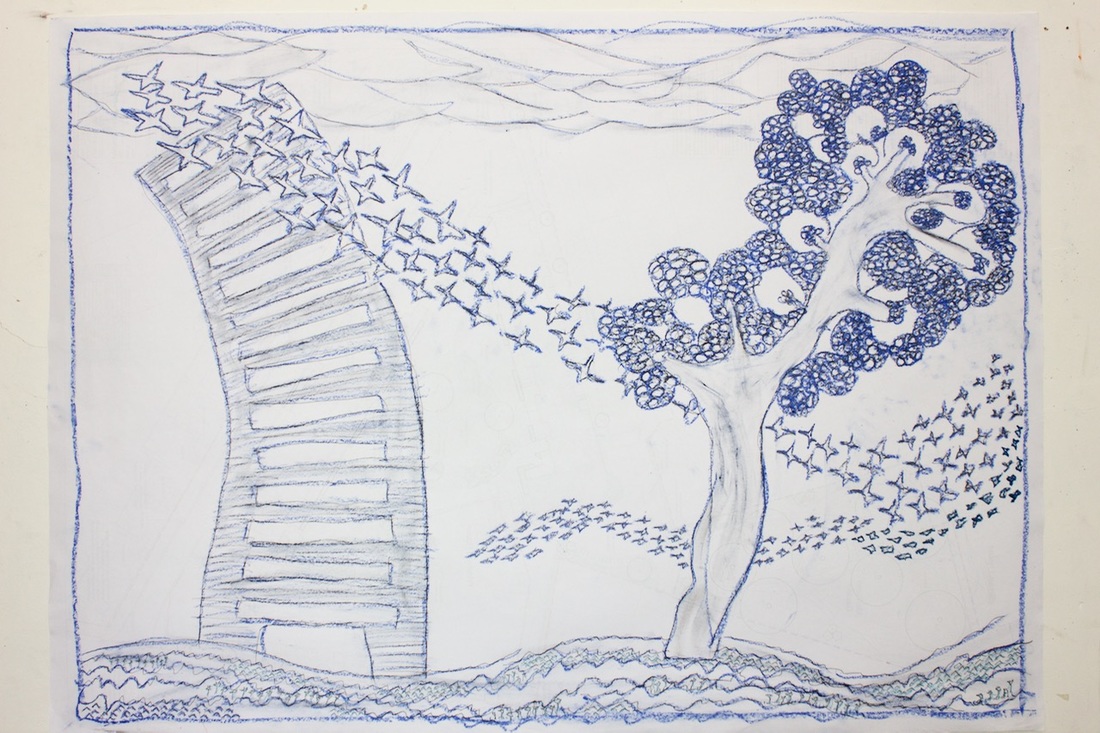

In 2010, when undertaking research for the film and art project, Flood Light, about the inter-related history of the Grand Union Canal and Westway (A40), I first came across the photography of Adam Ritchie. When I opened up that archive box and out popped these evocative black and white prints of children in a raw concrete space, I vividly recalled the 1970s and my own childhood. I was the first person in decades to contact Adam about these photographs and in the process discovered he was one of the founding figures of the Westway Development Trust; the unique 23 acres of land under the Westway flyover that was fought over and gifted for the benefit of local people. In 2015, I had the pleasure of interviewing Adam. He reflected on his father's legacy, the lows of education, the highs of the swinging 60's, community activism and on his fragile, but important photographic collection. It is timely to revisit the social conflict of the 1960s in North Kensington after the tragic Grenfell Tower fire. From a ruined landscape of houses demolished for the making of the Westway, residents were able to organise themselves and guide the woefully out-of-touch local authority into the making of community spaces and facilities. I’m sort of a middle class person, though my great-great-grandfather was born a bastard. My father was a journalist and broadcaster with the BBC. During the war, he invented the V for Victory Campaign. It was a big letter V that was chalked up all over the walls throughout occupied Europe by the people telling the Nazis that they would not win. This was a formidable psychological warfare campaign. He was very interested in the importance of the BBC being about truth. It couldn’t be like Nazi propaganda where they told lies and people were shot for listening to the BBC European broadcasts. I think I inherited the idea of the importance of truth and honesty from my father. I went to a public school which I hated as I was beaten every day for being the only socialist. The first day they asked you which way do your parents vote. I said they voted labour. I got hit. It was like that for the next few years. My father had a stroke and then we had no money at all for a long time. I got a scholarship to the French Lycée in South Kensington in the 1950s. Then I got another one to study at an American university in Massachusetts. I studied economics to start with because I wanted to work for the European Union. I thought that was the future for the UK. But the economics professor was so right wing, he took me aside one day and said, I don’t care what you do, I’m not going to let you pass anything in my department and I want you out of the college. This was because at his lectures, he said, if the workers could just observe the law of supply and demand and accept lower wages, then everything would be wonderful. But what about the workers, I asked? In the end, he got more upset because all the other students started to think ‘why should you just assume it’s okay for people to be poverty stricken’. I eventually changed to study English or American literature and I got on beautifully with that. The only non-fraternity place to live on campus was called Independence Hall. We each had separate rooms and there were a lot of women visitors. But one day the Dean said that for reasons of fire safety regulation we all had to leave our single bedsits so two people would share one bedroom and one study room. We all thought this was crazy, so I went to see the Fire Chief in the town. He said there was no regulation like that and didn’t know what I was talking about. But by the afternoon he had heard. He changed his tune because it was a one horse town; the college owned the town. About 2/3 of the students in Independence Hall upped and left the college. It was pretty shocking because a lot of them were in their last year. I left and went to Boston and tried to enroll in Harvard but that was impossible. In the end, I came back to England. I was very depressed. The whole experience was quite nasty. I worked at Better Books, in Charing Cross Road. I met up again with a friend called Nicole Lepsky who I last saw doing A and S Levels at the Lycée Francais in London. She asked me to come to a party near Oxford. I said, yeah. She was going out with a guy called John 'Hoppy' Hopkins. I met him and we got on very well. He was getting a flat at 105 Westbourne Terrace and it had lots of rooms. There were about 5 or 6 of us there including me. We smoked dope every night, listened to very modern jazz and someone used to read aloud, things like Samuel Beckett’s Murphy and At Swim-Two-Birds, by Flann O’Brien. We were always laughing our heads off. I always wanted to go back to America to see it properly. To get a Green Card in 1962 you had to have £400. I had £200 in the bank. I got a letter from my bank manager saying I had £200 in the bank. And then twenty minutes later I took all the money out. I went straight to the American Embassy, saying I’ve got £200 in cash here plus proof of another £200 from the bank letter. £200 plus £200 makes £400, doesn't it! And they gave me a Green Card. In America, I got a job as an economist at a place called Business International Corporation. I was hired to help give economic advice to the 100 top American companies wanting to operate in Europe. I got a loft and redid it completely. It had been a leather factory run by an alcoholic and his policeman brother. They made suitcase luggage straps, that’s all they did, nothing else. This loft was huge. I got on very well with the landlord who looked like a bowery bum. For some reason he got many of his clothes from his tenants; they threw them away and he would wear them. I don’t know why! His name was Seymour Finkelstein and he was a very pleasant man. He lent me all the tools and materials to do up this loft. I took off all the plaster from one wall, so it was a plain brick wall. I put in a bathroom and kitchen and built a huge platform to sleep on. I met Carola two weeks before I left for America. She was a typographic designer. I said, why don’t you come over with me! Two months later she left England and moved in with me into the loft. She got a job at Columbia University Press and did the typographic layout of their Encyclopaedia. In the end we were all evicted from the building. I think Seymour didn’t pay bribes to the fire department as it was illegal to have too many ‘artists in residence.’ You could have a license saying AIR2 meaning there were artists on 2 floors of the loft building. Seymour had 4 floors of artists and he wouldn’t pay the bribes, so they closed him down. Put padlocks on our front door and told us you’ve got to be out in 2 days. I found another place to live. One day while I was walking along a street, I saw a huge rat walking on the other side. It was walking quite nonchalantly, not paying much attention to anything. I thought, I’d really like a picture of this. I had a friend called Larry Fink who was a photographer. He had a darkroom just around the corner and I’d been talking to him about the images in New York I wanted to photograph. He said, why don’t you get a camera? I had recently just come back to England where Carola and I got married and I had about £150 from wedding money. I went out with Larry on a Friday evening to a big discount store and bought a good 35mm single lens reflex camera. On the Saturday I took lots of pictures and spent the whole of Sunday printing them in Larry’s darkroom. On Monday morning I was back in my office, with 15 good looking photos on my wall and the whole place, about 40 people working there, came by and said, 'Wow! These are really nice pictures.' The guy who ran the place asked me to photograph a Business International conference in Washington DC. I went down and took the photos and they got more orders for copies of the photographs than they’ve ever had using professional photographers. The head of the company at Business International, Bill Person, said, you ought to be doing photography and not economics. I said, photography is fine for a bit of pleasure on the side, but what’s serious is economics. He thought about it for a bit. He then sent me on a four day course to a company who test people to see what they were good at. It turned out I could be good as a lawyer, a journalist, a teacher. Nothing to do with photography. Bill said, “You should be a photographer. I’m going to fire you. You’ve got 3 months on full pay and you’re not allowed to come into the office except to show us photographs.” So I got sacked in this beautiful way. Only in America! He said something like it had happened to him and the change had been an important moment in his life. I went to the magazines and they all said, we don’t give commissions to people who have been a photographer for 2 months. I’d already saved up for a holiday trip to England with Carola and so I thought about what would interest Americans about England. This was 1963-64 and I noticed there were all these people in London who had important jobs and were around 22 years old. They were graphic designers, musicians, journalists. The fashion editor of the Observer was Georgina Howell, who was 23 years old. The fashion editor of The Herald Tribune in New York was 67. She was writing about young people and it felt weird. There were lots of people past pension age in New York running things. It was a cultural thing. In London it was all youth, youth, youth. I went to Glamour, a Conde Nast magazine, and said, I’m going to London in 2-3 weeks and I want to photograph these people, They are all under 25 and they’ve done really amazing things. Again, they said we don’t give commissions, but we will look at the photos when you come back. We might be able to publish a page. I came back and they published 6 pages and they gave me work every month after that. That was an amazing start. At the time, I made a film with a friend, Yvette Nachmias, called "Room 1301.” It was about the office environment in New York when she was trying to go down one floor from the 27th to the 26th floor. The door locked behind her and she couldn’t get out on any floor at all. She walked down 27 flights to the basement and out onto the street. There were alarm bells going and 6 fire engines around the front thinking there was a fire. She went back to her desk and didn’t say a word. It was quite a nice little film shot on 16mm. Before I came back to England in 1966 for the birth of our son, several interesting and important things happened to me in New York. I lived just around the corner from Tompkins Square on Lower East Side. This was a completely flat square with lots of pathways with concrete fencing on each side and some tiny patches of grass also surrounded by concrete fencing so you couldn’t get onto the grass. Mayor Wagner had a brother who was a concrete manufacturer. The city covered everything in concrete. People used to come to Tompkins square and had to lift their dogs over this 5 foot high concrete fence around every patch of grass. One day, the mayor started to build a concrete stage with a roof on it. There were diggers and this huge mound of earth next to where they were going to build this thing. They laid the foundations. The kids took over this hill of earth and they ran up and down it until it was smooth and wonderfully evenly shaped and not muddy anymore. It was the first thing that was alive in this whole square. There also was a change of government with Mayor Lindsay. His new parks commissioner, was Thomas Hoving, the son of people that started Tiffany's. The contractors said that they were going to come and remove the earth. The mothers realised that the earth was very important for the kids. Someone phoned up Thomas Hoving and said you’ve got to come here because there is going to be trouble with the contractors ruining the last bit of our square. The mothers formed a circle and hundreds of kids were all on the mound and the contractors were ready with their machines. Thomas Hoving arrived in a big limousine with police motorcycle escorts. He talked to the contractors and he came and talked to the mums. Then he walked up the hill and down again. Talked to everybody once more and then said: I think it should stay. They called it Hoving’s Hill after this. I thought this was very exciting. It was political, very direct and everything was right in front of you. Also the fact of the mothers taking ownership of the space was very interesting. There was one other thing in New York that was also an inspiration to me. Hoving fenced off a small bit of Central Park and set up poles every 3 feet and hung canvas from one end of the poles to the other. There was a 3 foot by 2 foot high rectangle of canvas attached to them. Brushes and paints were supplied. And it was called Painting Day. People came and painted all day on both sides of the canvas. I think they burnt the whole thing when it was over. Then the picket fence was taken down. I thought that was fantastic and it was all done in one day. I came back to London with these two things buzzing in my brain. I went to see Hoppy and he’d set up the London Free School in North Kensington. They met and discussed things, had classes in whatever you wanted to know about. There were philosophers and writers and artists. They probably used the All Saints Church Hall for quite a lot of stuff. I think one of the things they organised was the first Carnival in London. It was not anything remotely like what we have now in Notting Hill. Rhaune Laslett and Hoppy started it. They just thought, let’s have a festival, This was about 1966. It wasn’t really organised and I think it was gently raining. I saw about 20 or 30 people walking past where I lived. They were singing and dancing and having a nice time. But they also got permission for an adventure playground where the houses had been demolished for the building of the Westway motorway. They put up a rather beautiful painted sign saying London Free School Adventure Playground - Come and Play. I went there and saw it. It was all demolition rubble about 5 or 6 feet below the pavement and there was a brick wall all the way around to stop people falling into the rubble. And there was a plank against the wall. If you were athletic enough you could maybe slither down this plank. The kids did it without any problem. I never saw an adult there except a bit later. The kids built things out of the rubble from some of the 600 or so demolished houses. This was Acklam Road between St Ervans and Wornington Road. So quite a large site. And there were all these wonderful things being built there by the kids out of the rubble. I thought they need a bit of material help. I bought two hammers, a saw and huge bag of nails and hid them under the rubble. I came back a few days later to see there was a new building. It was really bigger than what was there before because of the nails and tools. I was very excited about that and told friends. We all went to see this building a few days later. But the thing I had described in such detail wasn’t there. Instead there were 3 other buildings even bigger and better. I just thought that was fantastic how kids and people could just do things. All you needed to do was just twist it a little bit. God knows, we need a little help at times! There is also the innate impulse to do things and to have the opportunity. There was all this rubble, What do you do with it? You build buildings, that’s what you do with it! I went to a meeting of the London Free School at the All Saints Church Hall in Powis Square when they said that this is the last meeting. I said I’m really interested in doing something with the adventure playgrounds idea because they are going to build the motorway and this has got to be thought about. What are we going to do underneath the motorway? There were 5 or 6 people who joined me including John O’Malley. We formed the North Kensington Play Space Committee and met at my place for 3 or 4 years after that planning, talking to people and writing letters; I must have written 1000 letters. I was working nearly full time on it for 2-3 years as well as teaching photography at Central School of Art. Adam Ritchie's photographic prints of organised play schemes under the Westway, 1968-69 Kindly reproduced by Adam Ritchie and RBKC Local Studies and Archives As the motorway was being built, we asked for a meeting with the Greater London Council. They agreed to this and phoned to ask were we bringing anyone else. You could hear their jaw dropping as we said, yes, we’re bringing Sir Hugh Casson who was an architect and planning consultant to the Queen and Ottawa and 17 other cities. He was a big deal. And we're bringing the secretary of one of the largest charities in London. We are bringing Peggy Jay who was the parks committee head of the previous local government. She knew everything about how things were done. And we had Ilys Booker, a sociologist, with an international reputation, who was working in Notting Dale and she supported us. It was an extraordinary list of people. When we came to the meeting there were maybe 60 people in the room. They had all their officers and secretaries and committee people. We came with our lot who all gave fabulous speeches. We also had a half page article in the Times and a leader in the Guardian all in favour of our plan. They agreed to further meetings. Later they said we couldn’t have community facilities under the Westway, because they had planning permission to build a car park under the whole of the motorway. They were going to build a 22 foot high concrete wall shutting off the underneath of the motorway for the car park. It would just become this awful space. One of the imagined reasons for the motorway was to reduce local traffic and if you got a huge 8 acre car park underneath the bloody thing, where are the cars going to come from? They are going to come off the motorway and park there. Everything was so badly thought out. We hired a barrister to contest this. He wrote a letter to the Transport Minster asking whether they had planning permission. Just by chance we knew Donald Chesworth, who had been on the Planning Committee 15 years before at the London County Council. He said, I don’t remember agreeing to a car park. I phoned up the Town Clerk of the GLC and said could we possibly have a copy of the minutes of that meeting at which the planning permission was granted. There was a gulp at his end. The next day the 22ft concrete screen slabs that they bought or had commissioned, thousands of them, made to wall off the whole of the underneath of the motorway, was stopped. I don’t know at what cost. They had to abandon the whole thing. But we were a bit nervous about chasing them legally because we were trying to get their support for our scheme. It was swept under the carpet. But they had told the Transport Minister that they had planning permission and this was a lie. If anyone thinks that officials are telling the truth, they may not be and you need to double and triple check. I forgot to mention that we had someone from Kingston University Architectural Department who designed a pamphlet for us. This had an air map of North Kensington with the motorway on it and our plans for the spaces underneath. We also got sponsored by the British Road Federation because we were the only people suggesting a possible social use of a motorway; but I was really against roads impinging on everything without any obvious advantages. BRF gave us a stand at the motor show which would have cost us thousands of pounds and they paid for all our materials. We produced this 15 or 18 foot long map of the motorway cutting across North Kensington showing its beginning and end. At public meetings we stuck this map on a huge series of boards and talked about the whole thing and said - imagine you’re a bird looking down on this, this is what it looks like. So people who didn’t read maps could get this scene of what they were proposing to do. And we gave out bits of paper and loads of magic markers and they could write down what facilities they wanted and where it should go under the motorway. It was real site-specific thinking. We were clear that we couldn’t put our own ideas forward. So all of the ideas were from peoples’ suggestions at public meetings and by talking to people. Almost everything suggested was practical and sensible. I was knocked out by this. We also went to see a big London charity and discussed it several times with them, A wonderful man ran it called Tony Woods. He was excited about what we were talking about. We said could you put aside money for when it is needed. And he said, I can’t exactly remember the amount, but something like, I can put aside £20,000. It was serious money, He said he’ll put it forward for the next 3 years so that it will be available when needed. We worked with an insane confidence of thinking of things like that. If you are a little tiny group flaffing around on the outside of this circle, there was no reason why you’d think of things like that. But we did. I think our political thinking was pretty good. There was no possibility that I could have done any of this without John O’Malley. He was absolutely a rock. He and his wife lived and worked at the Community Workshop in St Ervans Road. They were community organisers. Jan worked on an area that I thought was more serious, housing. She did a huge amount of research and had a real strong framework of understanding what the problems were and how to solve them by helping people. Many commentators said that North Kensington had the worse housing in Britain. It really was overcrowded, with decrepit, often disgusting, bad housing There were 15-16 people living in a house with one toilet that was overflowing and with no heating. Rachman-type landlords who didn't give a shit about these people. Horrible! John and I organised play projects that were temporary schemes and hopefully would become permanent. So for example, we ran the Summer Play Project in 1967 that had 200 students from all over the country coming to help us. We got a disused school to house them. We got a grant to pay for a secretary and changed our name to the Motorway Development Trust because we spent all our time on the motorway scheme. We didn’t have false ideas of anything. This was quite important. We always knew that we couldn’t get what we wanted, which was for the community to have control over their own area. But we could do a hell of a lot better than just having a car park under the motorway. One of the principles behind the whole campaign was that we had to have fun while we were doing this. You can’t do any good if you are not enjoying yourself! The council agreed to setting up the North Kensington Amenity Trust that would run the spaces under the Westway. The council wanted to set it up with the Town Clerk as Secretary. This would have been a really poor organisation. We were quite good friends with the Charity Commission and suggested this wasn’t the proper way to set up a charity. It was a way of subsidising rates and so the council was put right on that and had to change the complexion of the organisation. We also had to have an independent chairman. The council chose an ex-ambassador and we then had middle of the road people. In my view, people who basically didn't want to rock the boat with the council. Establishment people. John and I weren’t allowed to be on the committee until we got the Charity Commission to insist on more openness and then got elected onto it. It was stultified for many years because of the lack of imagination of the council in dealing with it. They probably let us on in the end because they didn’t have any ideas and we had quite a lot. At all our meetings with Kensington Council we did the soft cop, hard cop thing. John would go in with his Arran sweater and he looked unshaven and radical. I would go in like a posh kid from Chelsea. They couldn’t believe the radical things I was saying and were then surprised that John didn’t bite their throats and had these practical things to say. But the Trust didn’t like it. In the end, I got a job building houses in Wales in 1973. I stayed on as an elected member on the Amenity Trust for a year or so and came to London for the meetings. We had started with the idea for an adventure playground at one end of Acklam Road. Then it became a mile-long strip up to White City. A lot has happened that seems a lot better than a giant car park and some has developed based on community amenities rather than just commercial. We always included in our plans some commercial space because it provides jobs and some income. We have seen gentrification increased beyond belief but there is not much you can do about that with so little community controlling their own space. Original vision for community spaces under the Westway, 1968 Westway Development Trust consultation on how to regenerate the spaces, 2017 Adam Ritchie with the Latymer Mapping Project, 2013 Postscript: Photography I used a photo lab over the years because I was never terribly interested in printing. They also had all my negatives, 10-12 years worth going back to my time in America. It was stored at a place called Sky Labs which was in Maddox Street to start with and then moved to various places. I hadn't spoken to them or been in touch for about 3 or 4 years because I was building houses in Wales. I popped in and asked for a picture from my negs. They said we don’t have your pictures. I walked out and thought that proves that I’m not a photographer anymore. It wasn’t a tragedy. I didn’t go back in and scream or shout. I wish the hell I had now! They closed up their old shop and as I had moved a few times, there was no way to get in touch with me. They probably put it all in the skip. It’s very sad because I had some nice pictures. I think the ones of the kids playing were the best ones I ever took. I’ve probably got 10 prints left altogether from thousands of pictures. My colour slides and contact sheets of Pink Floyd and Velvet Underground happened to be in a bag in a parking bay under Trellick Tower which I hired for storage. The bay was broken into and wrecked with paint poured over everything. But they didn’t take or destroy this one bag which had all my Pink Floyd and Velvet Underground photos. They have since been published in thousands of books, magazines and newspapers and exhibited at the Tate, Liverpool, the V&A and the Whitney Museum in New York. I only take a few snaps now. There was something so free about taking photos then, less self-consciousness. www.adam-ritchie-photography.co.uk

1 Comment

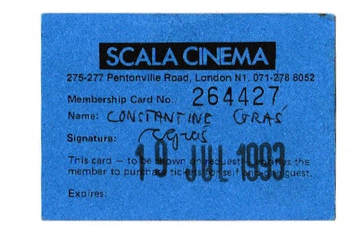

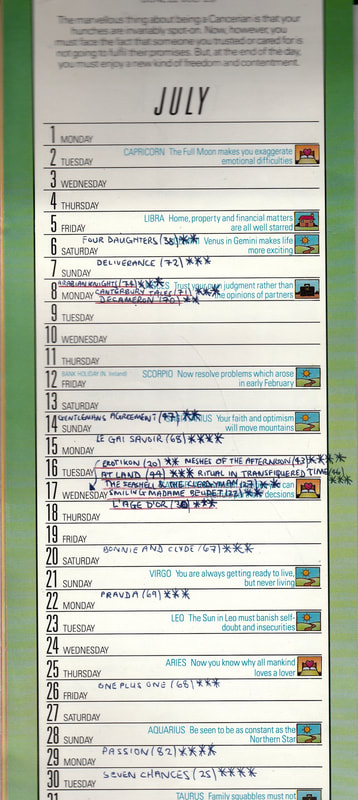

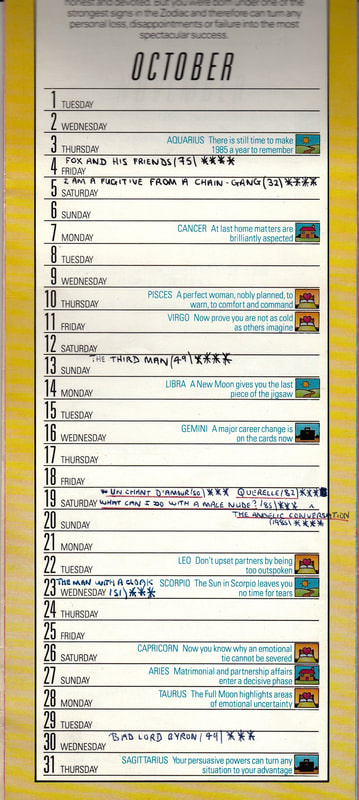

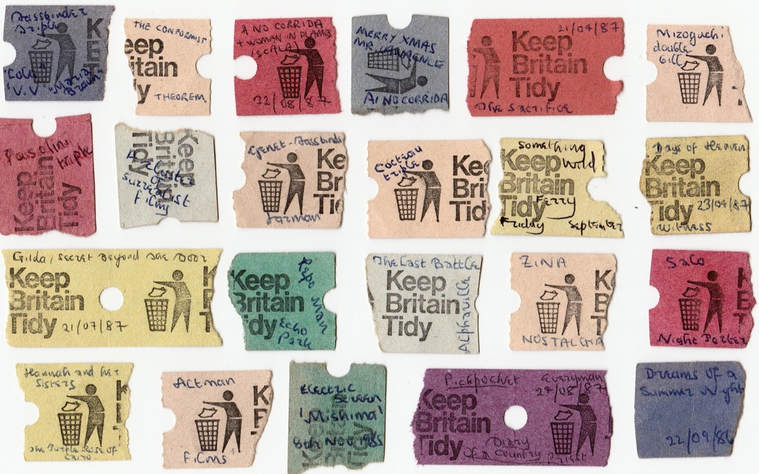

I recently treated myself to a double bill of The Angelic Conversation (1985) and Mirror (1975). I don't think any programmers have paired these two films before, but they resonate with each other, lyrically and visually, as well as offering divergent approaches to art based film making. Both were viewed on a computer screen, with the Jarman film rented online. However this screening of one film after the other was an act of homage to my golden age of cinema going as a teenager in the 1980s. After wee nippering at the ABC Edgware Road, I gravitated to the flea pit circuit that took in the posh Everyman at Hampstead and the grungy Scala at Kings Cross. During this period you could watch double or triple bill features in memorable combinations designed to shock and awe: The Exorcist riding on the back of Enter The Dragon; Terror followed by Savage Weekend (the rediscovered memory of Terror would inspire an arts project called The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle); Fassbinder double bills; and, not for the faint-hearted, a starter, main course and dessert of Pasolini films. Also, certain films that should not have been coupled, such as the groundbreaking In The Realm of the Senses (Ai no corrida). I’ve just looked over some calendars from the mid 1980s and was surprised to see how much film I was ingesting. There may have been a limited amount of TV channels in those pre-satellite days, but there was no shortage of films. Auntie Beeb and new kid on the block, Channel 4, had a public monopoly access to the film market. VHS was established and DVD was on the horizon. But to be able to see what your heart and soul desired, necessitated a trip to the picture house. It’s good to see there are plans afoot to design a Scala book, as the cinema produced lovely posters listing their monthly features. I usually hoard memorabilia, so I can’t account for the fact that I don’t have a single calendar month from my membership of the Scala. Perhaps it might surprise you to hear that I really can’t watch films anymore. I rarely go to the cinema. When you are in the business of producing art, there seems to be little time and perhaps inclination for seeking out art in your down time. Maybe it was also studying Film and Literature at the University of Warwick for 3 years and the celluloid feast we had as students, watching each film twice for close textual and semiotic analysis and which also included us projecting the 16mm prints sent up from the BFI. After ingestion, overdose?

While I had an eclectic taste, enjoying the classic narrative joys and happy endings of Hollywood cinema, it was the European art house movies that really tickled my fancy; although they did on occasion stretch your patience; the 317 minute cut of Bertolucci's 1900 seen at the Curzon Bloomsbury springs to mind. In the 1980’s, the work of two artists shaped my aesthetic outlook and personality: Derek Jarman’s gay-punk sensibility that pricked the constricting norms of Thatcherite society; and Andrei Tarkovsky’s metaphysical exploration of memory and haunting use of landscapes.

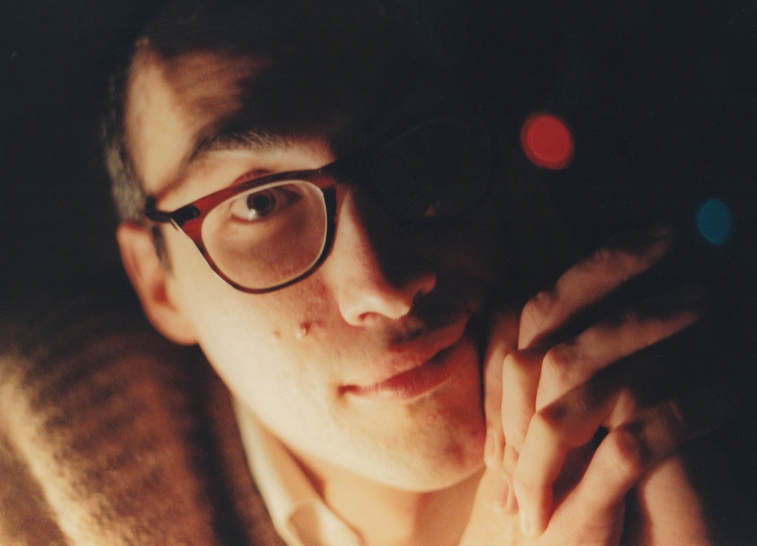

I had to write an essay to get into Warwick University (in addition to A level grades AAB and a medical examination!) That essay was on Derek Jarman’s The Angelic Conversation which I saw on both the cinema and TV in 1985. The film was a jittery and sensual evocation of Shakespeare’s Sonnets as read by Judi Dench. It was set in a timeless landscape of grainy, every changing palettes of muted colours that condemned men to drift and brood and lock horns in the slow-motion ritual of love and sex. The Sonnets themselves have an enigmatic quality that has divided scholars; the first 126 addressed to a man and the last 28 to the dark woman.

Abbey Fields, Kenilworth 1989

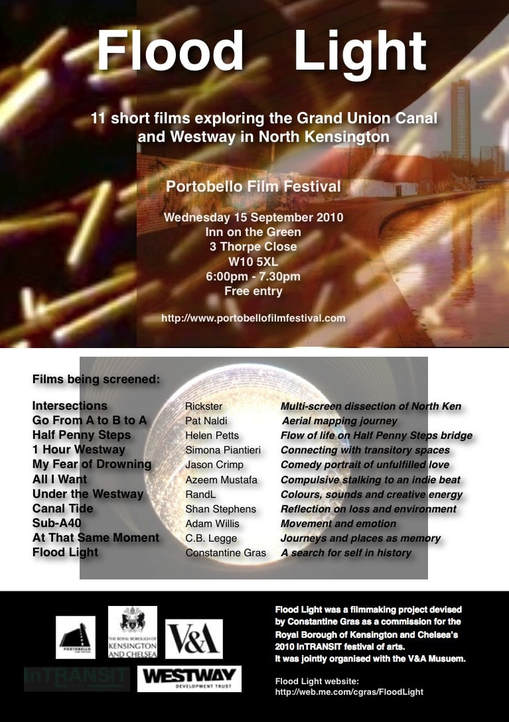

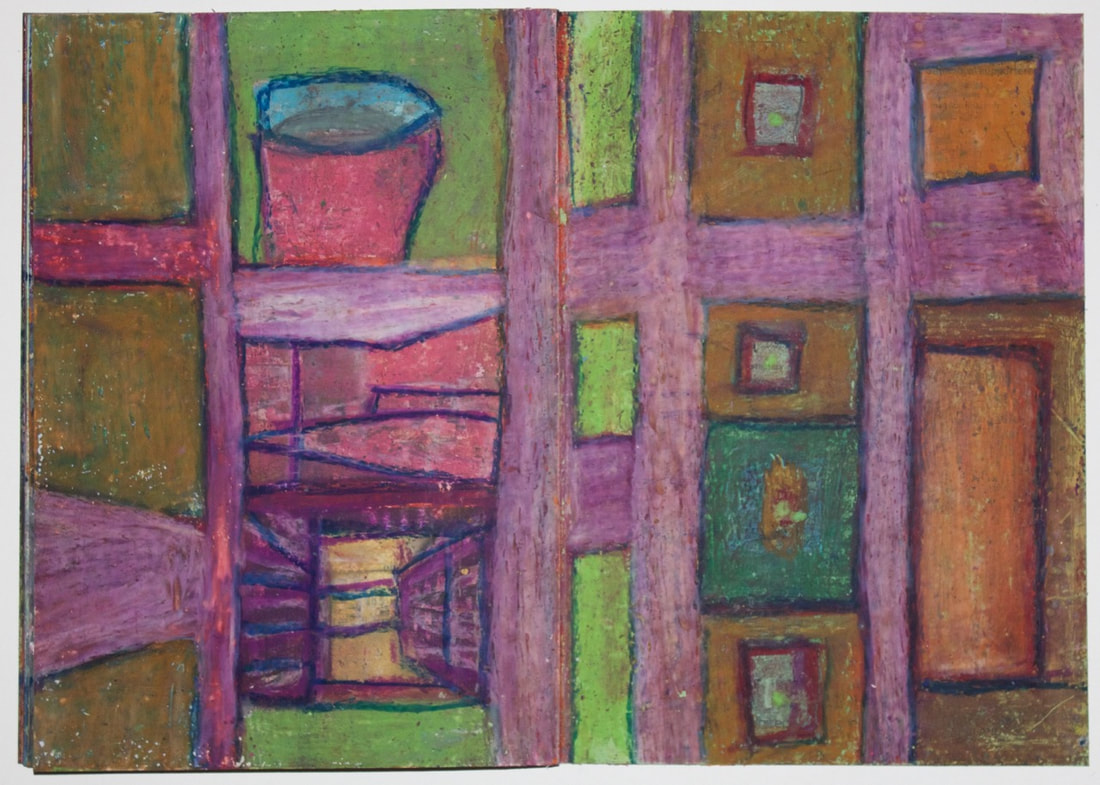

As a young man, dressed in my 1940’s suits, I seemed to wander in and out of both Jarman’s and Tarkovsky’s filmic landscape. I even had a dramatic film, This-That, inspired by my personae and made by fellow student and dear friend, Jacob Barua. That film was recently digitally remastered and there are plans for a sequel that updates the character into the 21st century. I better watch these spaces. After Warwick, I attempted to forge a part-time career as a stills photographer and eventually made it behind the film camera. Apart from several minor juvenilia works, my first real directorial effort was Flood light (2010). This was made for InTRANSIT festival of arts and I made a connection with the V&A Museum, later becoming one of their artists in residence. Although it wasn’t consciously conceived of as such, this film employed the strategies of what we might term the art film. The film used dialectical montage rhythms around the Grand Union Canal and the elevated road in the sky, Westway (A40). It fused together autobiographical elements (school books, carpentry tools), archive photos and film from the 60s and used period locations at the V&A to meditate backwards and forwards in time. There was no narrative drive or dialogue to guide the viewer in interpreting this stream of visual consciousness. A dripping soundtrack connected up images from beginning to end. It was a film about my urban identity in North Kensington. How I was able to intellectually and emotionally connect with water and concrete built environment. It is a film that has been aptly screened under elevated motorway roads in East and West London and in the Whitechapel Gallery. It has all the sins of a first film, but is probably my best work thus far.

Poster for Flood Light, 2010

In addition to making films, i have also curated film programmes and these have been useful platforms to support other emerging filmmakers. These are not exactly double or triple bills, but short films screened one after another and all inter-related on a specific theme. Flood Light was screened as part of a programme in which I invited other film makers to journey with me across the landscape of North Kensington. Local residents were also supplied with film cameras and edited their films at the V&A's Sackler Centre for Education. A panel from the V&A, Westway Development Trust, British Waterways and RBKC Arts selected the Best Film submitted for Flood Light and this was Intersections by Rickster. Henrietta Ross from British Waterways commented on this film: "I was very impressed by this. I thought the format worked really well conveying a great sense of movement. The sense of a journey was represented well, as was the great variety of activity going on around the location and the varied perspectives the location offers on West London life. I thought the different views were matched really effectively with a great eye for detail. The combination of colour, movement, stillness, nature and community activity was really engaging." It was also a pleasure to see an early film from film maker Azeem Mustafa who has since gone on to specialise in martial arts film. Simona Piantieri has also subsequently produced exceptional work. I particularly like the documentary film she made with Michele D'Acosta called A House Beautiful (2017). I followed up Flood Light with another curated programme called West Ten Fade Out (2013). This was able to showcase the film making talents of Dee Harding and Sandra Crisp. When I was the V&A Community Artist in residence based at Silchester Estate, I put together another selection of short films called Home Sweet Home (2014) around the issue of housing and domesticity. I particularly like sourcing archive films and using extracts that provide ironic or amusing contrast in the programme. I used two such extracts in Home Sweet Home and they are animated films from the Wellcome Collection. The Five (1970) is by Halas & Batchelor and opens with a young girl coming home from a party and going to bed; but her pooped toes take on a life of their own. The opening 7 minutes of Full Circle (1974) has exquisite art and animation by Charles Goetz that shows the development of city living and the possibility of over-population in the future leading to the collapse of civilised life. I have also tried to use film to connect residents with the history and social issues in the area in which they live. One example was a free screening I arranged of Leo The Last at the Gate Cinema in 2015. This was and is a profound film that connects with Lancaster West estate and Grenfell tower. I even wanted to screen this on Lancaster West estate for residents and the housing authority but circumstances conspired against that. The residents were locked in dispute with the Tenant Management Organisation over the Grenfell building works. I was commissioned by the TMO to make a short positive film of this regeneration taking into account the residents perspective. The film I delivered was a one hour long film completed in 2016 and called Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate. It was based on the life stories of seven residents. This was not a straight forward documentary with people speaking to camera. It is voice over set against the architecture of the estate. Although that film was deemed not fit for purpose by the TMO and fell into a state of limbo, I know that it really bonded me with residents in the community who have since become good friends. Hopefully it will have a proper screening in the near future. I have other footage that is strictly reserved for the police investigation. It isn't a good feeling to have art work that is delicately tied to the tragic events of Grenfell. There is no awe, just the shock.

2015 Poster for programme of short films, including rough cut of Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate

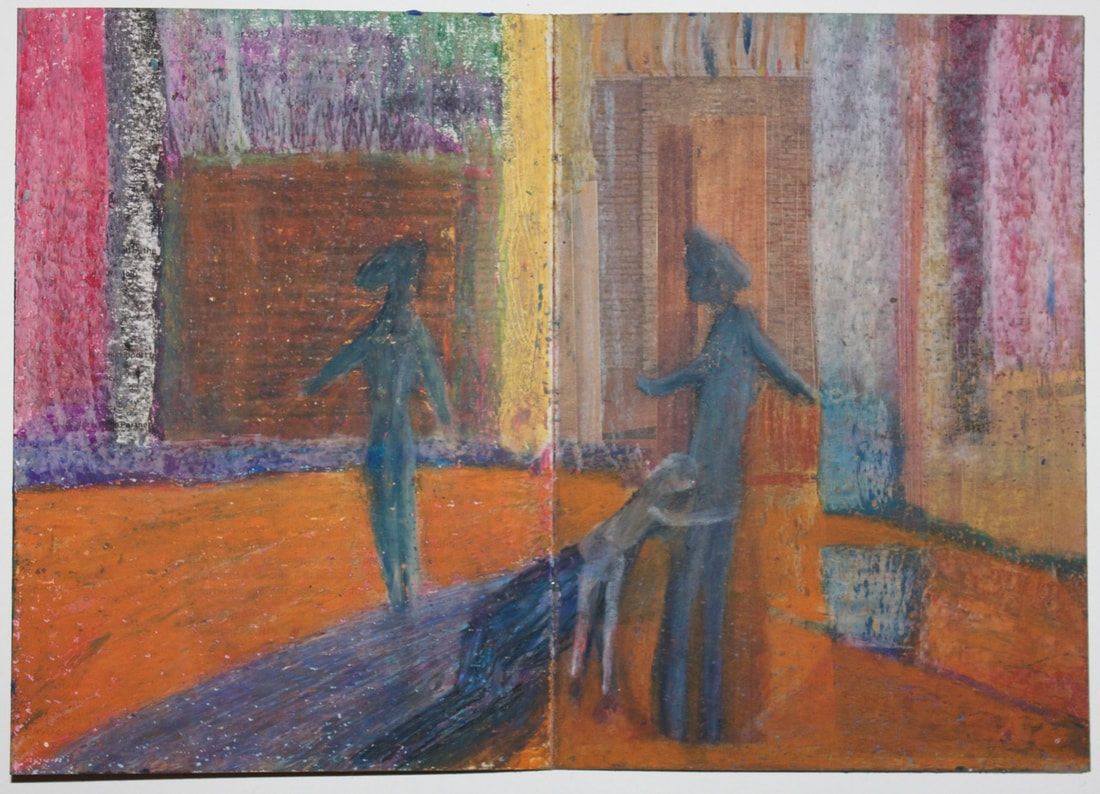

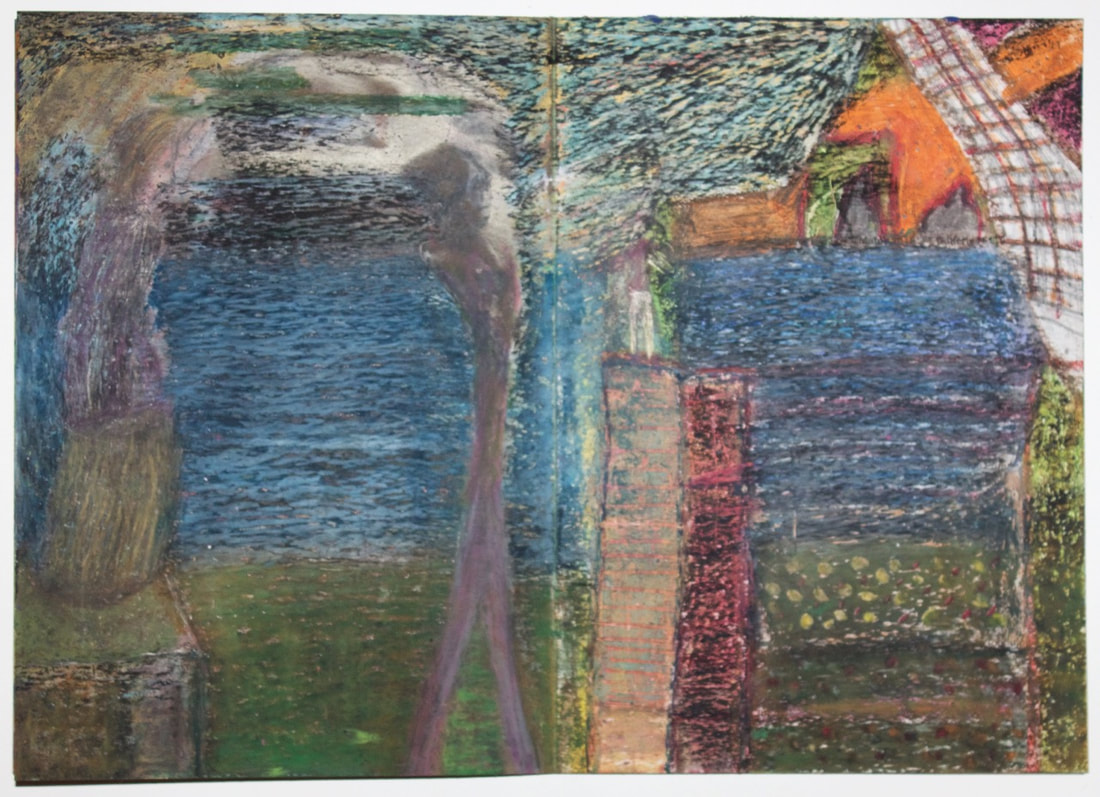

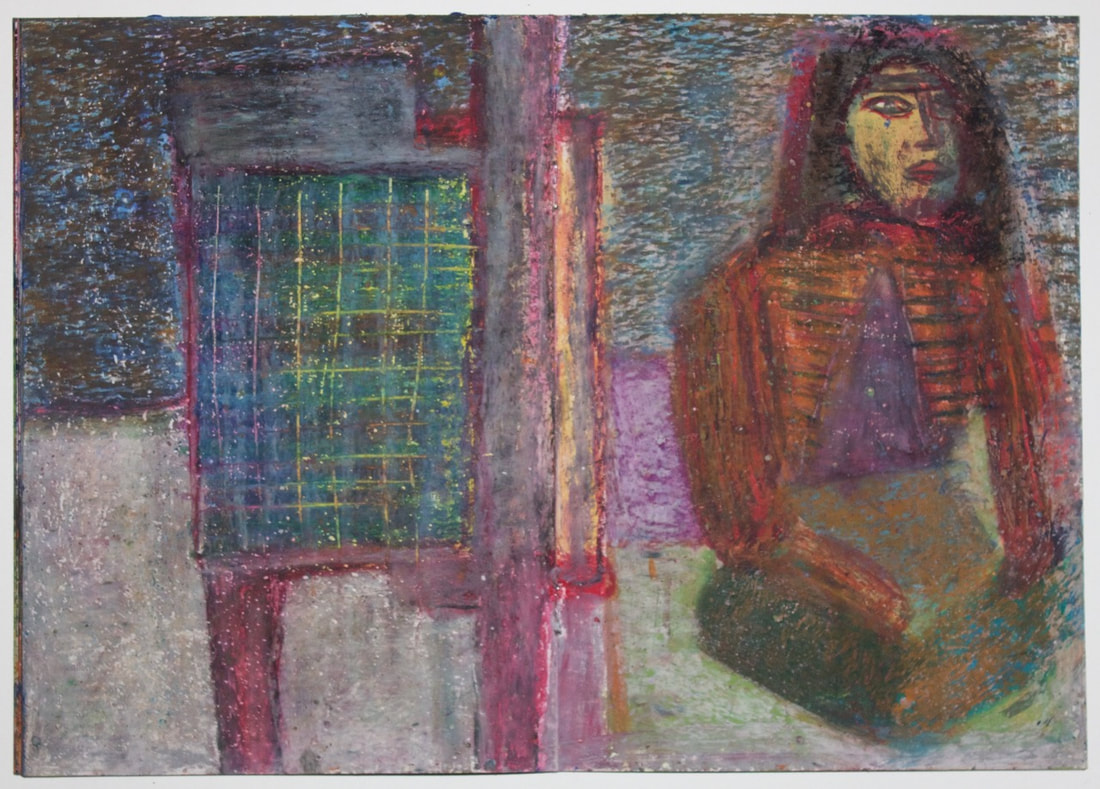

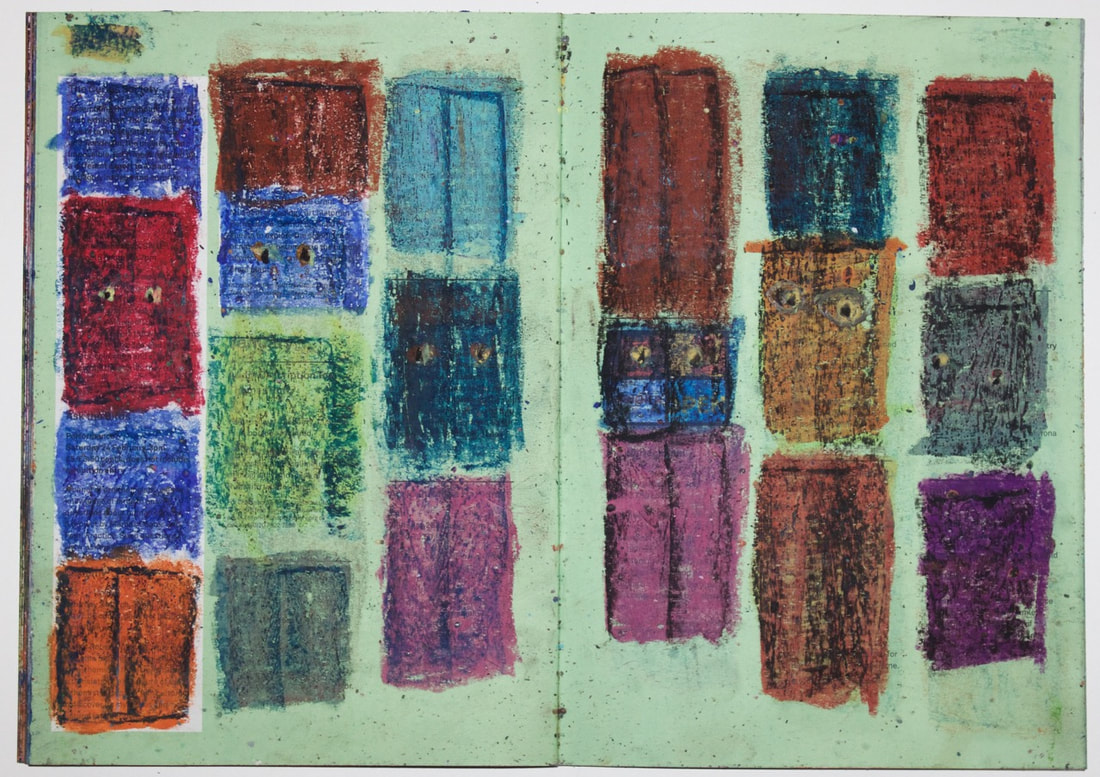

As I think of film, I draw and vice versa. I visualise films in my mind and these invariably start off as storyboard type drawings. The reality its that most films never get off the drawing board. But with the combination of drawing and writing, perhaps I can release some of that pressure cooker tension of being a multi media artist whose main aspiration is to make films. Let me conclude this blog by visualising a meeting of sorts between Derek Jarman and Andrei Tarkovsky on Hampstead Heath. Nothing is impossible in art and film. I need you to imagine that both are simultaneously drawn to the area for the making of a film.

Fade in.

A young man materialises out of the bushes, doing up his trouser belt, exhilarated, out of breath. A trickle of blood flows from his lips. Tarkovsky screams in Russian: cut, cut! The actor has wandered into the wrong film. A grounded helicopter rotor blade whips up a force of air onto the billowing grass and almost topples over the camera. Cut, cut. The production assistant rushes over to the helicopter. The timing is all wrong and aviation fuel is expensive. Tarkovsky curses under his breathe. Then looking at the bemused actor and the apologetic pilot, he starts to giggle and can’t stop giggling. The crew look at each other unsure whether to laugh. Tarkovsky motions for the actor to stand still and for the cinematographer to train the camera on him. Smiles all around and the actor looks up at the sky. It is a bright cloudless summer evening sky. A few rain drops start falling.

Cut to Jarman lining up his shot on the other edge of the heath, near a pond. He has torn up the script (that didn’t seem to be working) and is waiting for something to happen. His actors have got lost and a search party has been sent out. The rest of the crew have gone off for a tea break. A woman in her fifties dressed in a flowered dress walks into shot and sits on a log in the distance. She catches Jarman’s eye. He goes over and speaks to her. Hello, are you waiting for someone? She shakes her head in a combination of yes, no and don’t understand. He tries again. Would you like a cigarette? She nods and takes one. While lifting up the fag to his match, Jarman notices a raw burn mark on her wrist. Jarman wanders back to his camera. He zooms onto her. They hear the sound of a helicopter in the distance. She looks up in expectation. She appears to be acting. Jarman thinks she looks Eastern European, maybe Polish or Russian. He starts filming her as she turns her gaze to the pond and the gentle ripples on its surface formed by the wind.

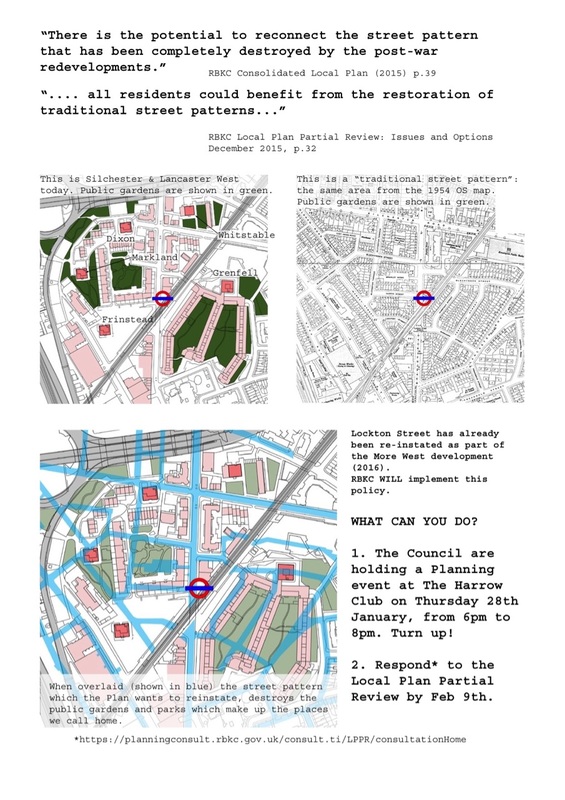

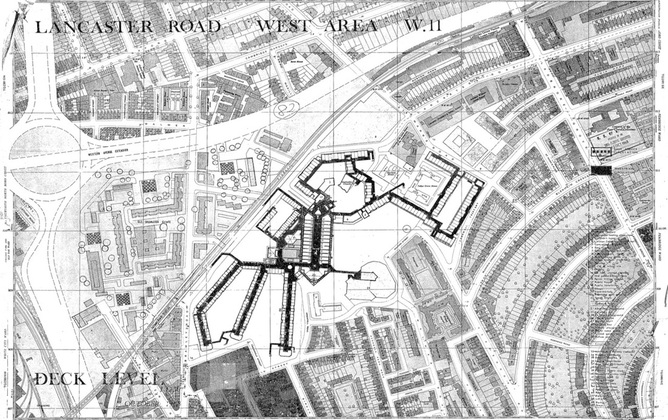

Fade out. It was a pleasure to meet up recently with Derek Latham at Lancaster West estate. He worked for the architectural firm of Clifford Wearden and Associates in the late 1960s making detailed drawings for Testerton, Hurstway and Barandon. These are the low rise housing units that radiate out from the central high rise tower and are known to locals as the "finger blocks". You might recall a previous blog featured Peter Deakins who was responsible for designing the early master plan. The planning and building process for Lancaster West was very protracted (1963-1981) and both architects left the practice before the first brick or concrete deck was layed They had different experiences and memories: Peter expressed frustration that the original plans were never built including a radical plan for building around Latimer station and connecting this with housing and a shopping centre; Derek campaigned about the housing crisis in North Kensington which the social housing development at Lancaster West was supposed to remedy. Ahead of out meeting, Derek kindly sent me his 1973 thesis: Community Survival in the Renewal Process - An integral part of the housing problem. This is very topical as RBKC council are currently consulting on a major regeneration at Silchester Estate and that will probably extend to Lancaster West in due course. The following are excepts from a statement provided by Derek and also an audio interview recorded at the estate. There are some fascinating comments about his involvement in the area and how it shaped the development of his philosophy of Gradual Renewal. "It’s wonderful to just come and experience the estate again. It was really interesting to see how the streets in the middle of the finger blocks have been altered and you feel they are ready for another transformation. So lovely to see that the green spaces between the blocks is just how we all envisaged it. The trees probably need thinning a little. Lovely in the winter, but in the summer I think there is probably just a bit too much shade. I have to say, the outside of the tower block with its new cladding looks really good and the academy is very impressive. At Lancaster West we tried to create scale and massing similar to that of a London Georgian square, but keeping the cars under the buildings so that the spaces between the building could be car free and provide a recreation and play space for those living around it. It was difficult to achieve the required density without building a series of tower blocks as was being undertaken on most other redevelopment schemes at the time. Our philosophy was effectively to lay tower blocks along the ground (in creating the "finger blocks") and instead of the vertical circulation going up the middle of the block by means of lifts, the circulation went along the centre of the block horizontally by means of walkways. During the development I became concerned when I discovered that a large proportion of the existing tenants who lived in the area were not to be rehoused. This was because they were effectively itinerant tenants living in the Rachman owned properties. Often two families to a floor sharing a kitchenette and sometimes six families sharing one bathroom and toilet. We think housing conditions today are poor, but I wish I had the photographs to show you the appalling conditions that these people were living in. They truly were slums. Not because of the way they were originally built as fine townhouses for single families with their servants but because of the way they were being exploited with little maintenance and severe overcrowding as the housing shortage at that time was so acute. You could look at a film like Cathy Come Home which was made back in the 1960s which fully explains the situation at that time. Because of my concern at the situation I joined Shelter. But I could do nothing to help the families that were in the Lancaster Road West area, most of whom had already been moved out to create a "ghost town". In fact the area was used as a film set just before it was demolished. All the buildings were painted black to create a macabre backcloth for some form of thriller or horror film. I am sorry, but I cannot remember the name of the film - I never did see it. (Derek is referring to the 1969 film, Leo The Last). But the council's intention was to continue with the demolitions northward into the Golborne area. It was in this area that we worked with shelter to encourage the residents to fight for their rights and fight for the properties to be improved under the new housing improvement acts rather than demolished. This was action that was taken directly to both the GLC and the borough. I remember one occasion when the borough said it was too complicated to change from demolition to improvement and the protesters wrapped up the Mayor's car in red tape. Shelter had also fought against the construction of Westway. There was a political party at that time called Homes Before Roads which actually managed to get some councillors elected onto the GLC. There was another occasion I recall when some activists in the upper stories of the houses in Golborne that were so close to the road demonstrated their proximity by firing with air rifles at the tyres of the cavalcade of cars that drove along Westway when it was opened causing several punctures. People were a lot more active with their politics in those days. By this time I was passionate about the need for a better solution to housing regeneration than the large clearances that were occurring throughout all the major cities in Britain. My thesis had examined the large council estates in Glasgow (Balornack Road Estate) , Liverpool and Manchester. But it also examined innovative improvement schemes rescuing tenement blocks in Glasgow, back-to-back houses in Leeds, and community housing in Liverpool 6 under something called the Shelter Neighbourhood Action Programme (SNAP), as well as some housing improvement being undertaken in Wandsworth by Ted Hollamby in the Brixton area. These demonstrated that communities survived better through the redevelopment process if they could remain where they were. Hence I developed the philosophy of Gradual Renewal - simply removing the very worst of the houses that were in poor condition and replacing them on the same street with new houses fitted in between those that remained. The philosophy was that in 15 or 20 years when some more of the original houses reached the end of their economic life then these too could be replaced. This would utilise the hammer and chisel and a small-scale builder rather than the bulldozer and the tower crane. It would avoid the decade of disruption that occurs with clearance and redevelopment. When I was first involved at Lancaster West, there was no question that you just pulled slums down. They had been doing it since the 1930s and it was very important because in those days the houses were really badly built. There aren’t slums now. There are estates which have been vandalised, but more often neglected. Maybe because they are more expensive to look after than other estates, so they don’t get that extra money. But in the long term maintaining places is cheaper than pulling them down and rebuilding them. And that’s without taking into account social costs. In my experience the disruption to the community is usually not less than 10 years from the start of a development to its end. This is a good part of any child’s life. What are the consequences of that? They are enormous and they don’t get costed. That’s why to keep communities together, you need to make the change frequent but small scale. And to have a long term vision for slow redevelopment in stages. But the idea of wholesale redevelopment, running everything to the end of its life, is going to cause problems for people. I don’t know about the condition of Silchester estate but Lancaster West is good solid brick work construction. It's not some panels that are held together with rusting joints. I know in some cases quite a lot of the GLC housing estates had that inherent problem and that was never going to get resolved. You just have to say we cannot repair it. It if hasn’t got those sort of problems, why not find a way of achieving your objectives without pulling everything down. The principal should be to save and find ways of improving. How can we build an extra floor if we want to increase the density? How can we improve the walkways or insulation? Sometimes you might need to demolish certain portions. I wouldn’t be alive now without some pretty good surgery from time to time. But the point about the good surgeons is that they only cut the bits that absolutely ned to be cut and the rest of the organ keeps going. And if you look at any community estate, it's like a living being and will need some surgery. But surgery isn’t death by bludgeoning and waiting for a re-birth. Nobody survives that well. The current housing crisis is bonkers. It’s clearly about not building enough houses because they haven’t worked out a way to fund it. And I don’t fully understand it. There is a lot of capital tied up in this country and basically its not quite needing a PFI because that is for too heavy. All you need, in my view, is to give a reasonable tax break and guaranteed longevity to major institutions to be able to invest in housing. It is a lot of investment and it needs a long pay back period. It’s not a quick fix. But if you get it right, it should be a good fix. Social housing should have a stability to it that even private housing doesn't. People like the Peabody Trust can demonstrate how it's done. I can’t understand why the government has not taken that model and gone with it. Although it's a Fabian model, it still fits very strongly within the conservative ethic of using private finance to help people to do things and to see it as a long term investment. You could progressively allow a proportion of houses to be purchased each time as long as that money is recycled into the new houses. But that's got to be sustainable and they have never seemed to be able to get the model to work. " Campaigning poster designed by Dale Teller and circulated by We love the Silchester Estate.

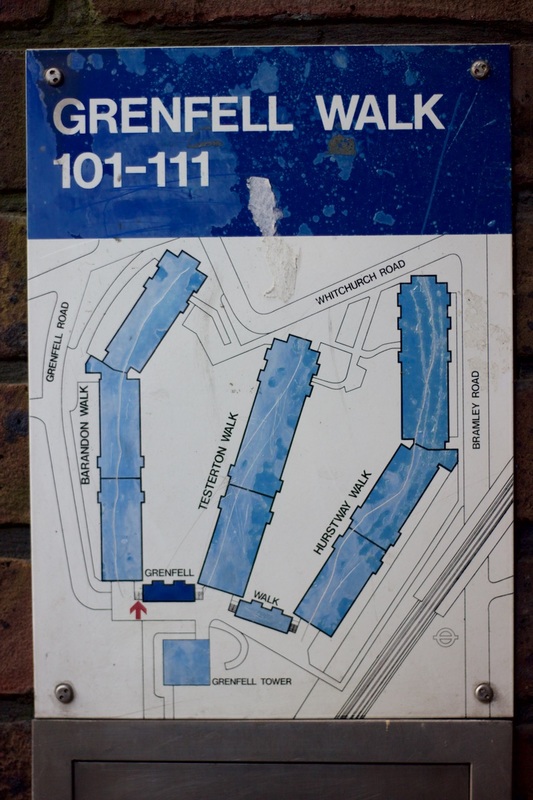

When post and pizza deliveries, family friends or council reps, come and visit Lancaster West for the first time, they have to navigate the complex lay out of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea's largest estate. Are you going to the tower block - Grenfell tower? Not to be confused with the four adjacent towers that are on Silchester estate. By a smidgen (ask a pigeon) this is the tallest structure in the area. So whether approaching by train or bus or foot, it should be the landmark to orientate yourself. The tower currently has scaffolding and building works. However since the regeneration, the entrance has been located to the upper walking deck and the floor levels have changed. Okay. You didn't actually want to visit the high rise. So are you going to the finger blocks? This is the charming local expression for Hurstway, Barandon and Testerton, the low level housing blocks. Each one radiates out from the tower and has at its heart, a simply splendid swathe of grass. Perhaps you didn't notice that these units are actually built above street and ground level garages. You don't really want to end up down there if you can avoid it. Are you lost? As we are temporarily lost, perhaps I can take advantage and guide you on a historical diversion. Both Grenfell tower and the finger blocks were the first stage of building for the estate and illustrate the design ideals of the 60s architects, before 70s politics (oil crisis, three day working week, labour shortages) and changes in thinking to estate building took hold; this is not to mention the complicating factor of the former Victorian baths on the site of the estate, which became listed for several years, before eventual demolition in the early 1980s. As you travel around this estate, you do so partly by elevated walkways or walks built into the middle of housing units. Many of the decks have now been removed. However an understanding of their origins might make our journey around the estate more comfortable. Do you remember Peter Deakins? He was one of the original architects of the estate who we met in a previous blog. He talks ruefully about the early masterplans where blocks were unified by walking decks above ground level and segregating people from traffic. At the centre of this modernist vision were a shopping arcade and business offices. These were never realised; however one section of underground garages was subsequently converted into Baseline business units. The estate was planned in the 60s, build in the early 70s and only fully completed by the 80s. The latter stages of the project were taken over the borough architect and other firms who were building lower density housing and these can be glimpsed at Camelford, Clarendon and Talbot Walk and also at Verity Close. The estate has also incorporated housing stock that was build before the 1970s. Also of interest, the original architects convinced the council that the area being redeveloped should have an element of housing for young professionals; this comprises the co-ownership houses at Wesley and St Andrew's Square. This is all good background material. But where would history be without art. Looking at the RBKC archives on the estate, my attention was caught by a reference to the appointment of Messrs. Kinneir, Calvert and Tunhill as graphic designers in 1972. They were tasked to create signage to enable visitors and residents to navigate around Lancaster West and Worlds End estates; both estates were built at the same time. Kinneir and Calvert gained fame for designing the signs used on the British motorway system. I recently contacted Margaret Calvert to enquire about her work on the estate and she mentioned how they produced on site trial signs. But she was never sure how these were applied, if at all. I think we can clearly see the graphic designer's blue thumb print in the old signage that is still in place. Modern signs co-exist with the old. So you can stroll around and follow the signs into the past. There is one signpost that I haven't mentioned. One pointing to the future. Many of the residents are seeing changes taking place to the local area and have grave concerns about the future of their homes. RBKC council is wanting to build more housing and to upgrade its housing stock. Complex and socially challenging signs in the making. Whenever I cycle down to Lancaster West, I pass under the Westway (A40) and I connect the signage on this former motorway to the directional signs scattered around the estate. As a frenetic artist (not enough hours to accomplish all those tasks), I'm often seen running around the estate at 70 mph; there are no speed restrictions in place here. Lancaster West estate is home to 1200 properties. I must not forget this as I re-imagine this space. It has a diverse range of people from all walks of life. I have the privilege of interviewing 6 residents as part of my film project. There is blood and tears and happiness invested in this built environment. No signs can fully communicate this. I am adding my own artistic layering. These will probably not help the post or pizza person. Better off following the conventional signs. If your a resident, the post or pizza is en route.

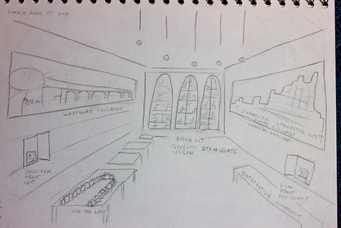

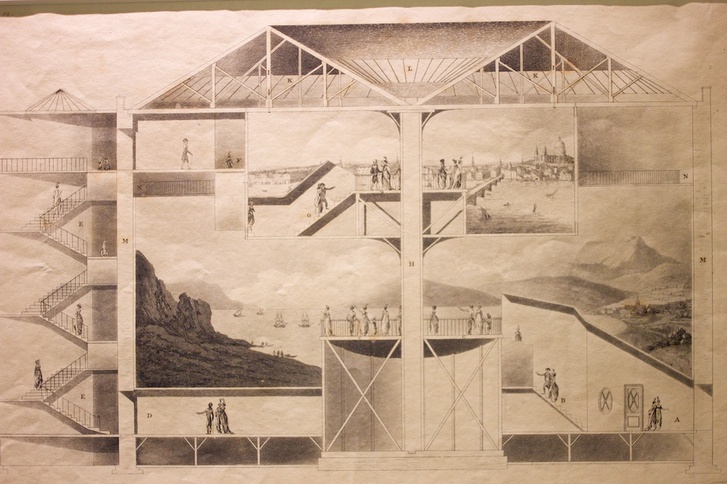

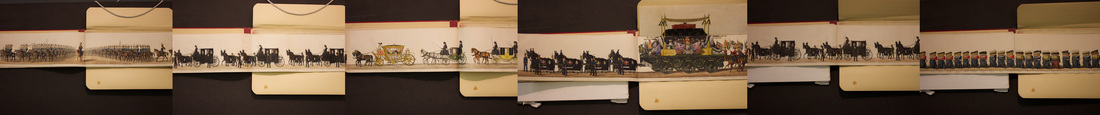

It might not be the final frontier. But this blog entry begins and ends with space. The big bang of the widescreen, large format and panoramic. A location for an artist to perform and connect with people. The contested politics of space, building homes and forging communities. First stop. Let me beam you to my non residential artist's studio. All artists cry and bleed for a space. This is nothing new. East London currently rules the roost, but in the past artists would look to this stretch, west of London, for verdant grass and fresh air. William Mulready was one of the first artists to settle in Kensington in the first decade of the 19th century. He shared digs with fellow artist John Linnell at Kensington Gravel Pits and then had a studio house built for him in 1827 at Linden Grove (now gardens, the house is no longer extant). This was during the first wave of development for the Ladbroke Estate and Mulready lived here for the remainder of his life. Nearly forty years later, Nathaniel Westlake, having just converted to catholicism, has his architect friend, John Francis Bentley, design a house for him in Notting Barns. Westlake did not stay here for long. We can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. His house is still standing and looks out of place next to the Lancaster West Estate. Mulready and Westlake are both closely associated with the birth of the V&A Museum and have work on display. In terms of art, studio space and the V&A, I am following in their footsteps; more of this anon. During my V&A Community Artist residency, I have that precious commodity for an artist, studio space. I am not based at the museum like the other resident artists. I am a tenant of a flat whose rooms can be sculpted, wallpapered, improvised. It's an in-between space, a former council property, that will become part of a mixed tenure housing. No one will care if I artistically trash it as demolition is due next year. I'm conscious of being the last in line. Leo The Last. The last house demolished. I've explored these in previous art projects. Now. I'm living out my very own kitchen sink drama. What about the medium or mixed media of space? Artists are always grappling with this technical consideration, whether it's processing on a computer or via more traditional craft techniques. I usually compose an image through a viewfinder of a camera or a sketchbook often leading to 16x20 inch drawings; this is a legacy of working with photo paper formats in a darkroom. There are also multiple dimensions to my residency: how art relates to community and housing and architecture. As I want to share and encourage others to participant in these processes, I need to think big as in large scale. This is new to me and will present its own set of challenges. I also need to engage with my immediate neighbours on the street, residents in the estate, people in the ward, across the borough. An audience that might not understand "art" or perhaps even know who the V&A are. As I begin, so I end. Everything is hurtling towards a date in January or February 2015 with an end of residency event at the V&A. This is in the lunch room for visitors to the learning centre. However being the V&A it is no ordinary lunch room. It has a cinematic sweep, certainly from the top down. Even wall lined cupboards gets one thinking of spaces within space. I'm looking at constructing panoramic displays here, perhaps of the Silchester and Lancaster West Estate and its residents. This will include film of the new housing development taking place and the new community that is forming. Also perhaps a representation of the Westway (A40), a built structure that dominates this area of North Kensington. Can I also chuck in some "stain-glass" imagery for the aesthetic thrill? On August 18th I hosted an open day bringing some of these issues into focus. I did wonder how many people I could safely fit into the studio flat and its 4 spaces (20 comfortably at peak capacity). It was a good idea to convert a large store room into a history room with archive maps and images. In total, I had 60 plus visitors. Delighted to see my neighbours on Shalfleet Drive popping in to see what all the fuss was about. This is important as I plan on working with them on a film project. There was a group visit from Open Age who took to my live drawing like ducks to water. Great to see old colleagues, including Adam Ritchie who was pivotal in establishing the community ethos for the Westway and the building of play spaces for children in the 1960s. The Mayor of RBKC Maighread Condon-Simmonds also paid a visit. She is a charming lady, really down to earth and digs the complex layered history of this area. In her thank you letter, she chimed in with my thoughts about the challenges of space: "You have made a truly interesting display in such a small space.....The north of the borough has so much more space than the south and it is good to see the new developments with good quality homes." For the exhibition, I also created a drawing installation called House with 40 Rooms. In each room there was an object. These objects were all from the V&A. I invited participants to use words or images in response to the objects in the rooms. Local resident, Maggie Tyler, wrote the following about her drawing: "I used to look out at a Stag's Horn tree and a round window in the wall of the house at the end of the garden. At night, I would see the silhouette of the foxes walking along the top of the wall past the round window. Then! The Neighbour moved out and the new neighbour built an extension. A modern extension that covered and destroyed the round window. The tree fell down and the view has changed. I now look at a modern box!" A few days later, I opened my studio during the rain-sodden Notting hill carnival. Sheltering outside my flat, I took pity on a group of performers and invited them in. Amos has been taking part in the carnival for over 15 years and we chatted about its history which is reflected in art work on display. New residents moving into More West from 2015 (once the flat is demolished and new housing built) will find they are on the western edge of the processional route. There is intense debate about the future of the carnival. Is it too big for the streets of Notting Hill? Cllr. Eve Allison, who has ancestral roots in the Carribean, believes there are compelling reasons for relocating the carnival to a larger green space. This would be a tremendous loss to the area and signal a departure that the carnival has lost its community connection. Down at the V&A, I've been reflecting on this and artistic precedents for panoramic art. Nathaniel Weslake has large upright stain glass and oil paintings (with associated mosaic) on display. I've previously commented on his smashing stain glass. This time I'm checking out his contribution to the Valhalla portraits. It seems apt that Westlake should choose as his artistic role model, Fra Beato Giacomo da Ulma (d.1517), a Dominican Friar who painted on glass at Bologna and is an obscure figure in the series. As Westlake did for da Ulma, I will likewise do for Westlake. Celebrate the art and allow this to percolate into my practice. This means moving into unfamiliar territory, but I'm up for the challenge. I can start digitally with photoshop and a literal following in the footsteps (see image below!) This is a simple tool to collage ideas and feelings about the construction of a pictorial landscape. Just the first step in a process of ongoing experimentation that will probably morph into craft and film. In the prints and study room, I perused an 1801 plan for a panorama in Leicester Square. This was presented as various walking and viewing points in a space shaped by architect and painter. Ingenious. I also marvelled at the skill employed in a fold-out book made to commemorate the Funeral Procession of the Duke of Wellington in 1852. It was made by Samuel Henry Alken and George Augustus Sala. The pomp and circumstance of this stately occasion made an interesting contrast to the recent carnival floats that passed by my studio. It connects with previous thoughts about creating work that fuses the historic with the contemporary. My art musing is only of interest when it translates into practical application. How to use art to look at the urban environment, the community spaces around my studio and the homes that residents have made here? How high rise residents perceive the new developments taking place below them? How residents in the shadow of taller structures respond to changes in light and air quality as the sun climbs and then dips into the West? How do I create a space for public participation in the process of making art? How will others want to comment on the world around them? I need to bear in mind that this might not necessarily tally with how I view the world. How will art be elegantly displayed for a follow-up activity of engagement? Can I bring this all together at the V&A lunch room as food for thought? I don't particularly want to end on a question, so offer this as a postscript.

I'm being managed by Laura Southall in the Learning Department and it was great to meet more of the team. I set them a 10 minute challenge to make some sculptural forms and showed them a few examples. If they ended up making a posh version of a paper aeroplane, that would be fine. Dah! They do all work for the V&A, pre-eminent design and art museum. Fold, tear and sellotape. Horizons west. Feels good. As a child during the 1970s, I would be consuming American popcorn movies at the ABC Edgware Road / Harrow Road. I recall When The North Wind Blows (man co-exists with tiger, 1974) and King Kong (men in conflict with giant ape, 1976).

Driving past the cinema and on another plane of reality was the author J G Ballard. Using the recently built Westway "motorway" from central London to his home in Shepperton, Ballard would pass the faded visage of the ABC with its local community displaced by slum clearance and road building. Further on he might spy the iconic Brutalist Trellick Tower and ponder the news headlines critiquing the social housing bloc that had degenerated into vandalism and tenant isolation. Nearing the West Cross interchange, perhaps Ballard has a vicarious thrill: hand caressing the steering wheel; foot poking the accelerator; car sliding and swerving, dangerously. This type of imaginative journey across the Westway would inform the subject matter of Ballard's seminal trilogy: Crash (1973), Concrete Island (1974) and High Rise (1975). Here's a quick summary for the uninitiated: Crash postulates a new form of human sexuality, born from the collision of car on car. A film adaption was vividly directed by David Cronenberg in 1997 and initially banned by Westminster City Council. Concrete Island is about an architect who crashes his Jaguar off the Westway and struggles to survive in a cocooned wasteland.This is slated to be a future Christian Bale film. High Rise (my personal favourite) has a classic opening. The protagonist, is admiring the view from his balcony and tucking into the tasty morsel of dog. Forget co-existence or conflict with nature. Welcome conspicuous consumption of the canine variety. In 2015, High Rise will hit the cinema screens. In these dystopian texts, Ballard is inverting the 1960s confidence in high rises and inner city motorways. These were seen at the time as progressive solutions to housing and transport needs. The Guardian recently celebrated Ballard, five years on (after death). Seven writers articulated what was unique and memorable about his work. Many visual artists and film makers could also reference the impact of his writing. I first discovered Ballard in the early 1980s as a moody teen listening to Joy Division. I revisited Ballard in 2010 when devising Flood Light. This involved a film making guided tour under the Westway and a re-enactment from Concrete Island. I have also made a trio of short films about the urban environment of the area with Ballard as a guiding spirit. At an art event recently, I met Ray, who during the 1970s lived in the twenty-floor high rise, Frinstead House, on the Silchester Estate. He may or may not have been turned on and tuned in. But he was definitely having apocalyptic visions of vehicles dropping out of the concrete sky. This was a nightmare that came true. Ray recounted, how one day, he witnessed a lorry crashing over the barrier and bursting into flames. He made a drawing of this incident (see image above). On a related note, I recently read an archive letter written by Fred Vermorel and published in the Times in Nov 1978. Fred is now Associate Professor of Communication at The American University in London. Back in the day he was living at Frinstead House with his wife Judy. They could almost have been characters in the scary fictional High Rise of J. G. Ballard. This is what Fred wrote to the press: "The noise is sickening. We live day and night with the unceasing thunder of motor vehicles, flat out and passing up and down the several slipways, and with the racket of passing trains (goods trains shunt through the night). All this noise hits our home directly. It is impossible to read, think or listen to music. I must confess that the vandalism which is slowly eating away this particular estate elates rather than horrifies us. How else does one react? The GLC is dead to transfer requests and there are no effective ways of protest or redress. If to destroy these places is some sort of crime, to have built them is worse! All around us are squatters, living in “derelict” (GLC owned) property. Built by speculators at the turn of the century, these houses are shielded from road and rail lines, are solidly built on a human scale, and have gardens. We would gladly rent one. But they will shortly be demolished. The GLC is still building unsheltered dwellings all along the Westway. With millions of pounds worth of expertise and materials, it is disseminating the suffering and environmental poverty I have described: factory farms for psychosis and barbarity.” Fred and Judy Vermorel were being driven out of their senses, but successfully campaigned to be rehoused. However we should note, they still found time while at Frinstead House during 1978-79, to write the first book about the Sex Pistols and produce a punk song for the Cash Pussies. During my forthcoming V&A Museum Community Artist in Residence, I hope to be based in a studio next to the high-rise, Frinstead House. I will definitely tap into the creative energy of Ballard and the DIY spirit of punk. Hopefully realise some long-term art projects that render and re-imagine the Westway and connect old residents in the high rises with new occupants of buildings currently being erected on the estate. I need to provide a counter-measure to the radicalism of Ballard and stereotypical perceptions about estate culture. Estates are not a car crash. Dig beneath the veneer and talk to people who have made this their home. There is a space here for high quality, multi-cultural and collaborative art.

I had the great pleasure of working with film makerDee Harding who has made a short film portrait about my art practice and reflections on the urban envrionment in North Kensington. She interviewed me in September 2012 at the former Latymer Project space; this was converted from a Nursery on Freston Road, W10 and is now part of a regeneration scheme for new housing at the Silchester Estate. Dee edited down an hour's conversation about the social and cultural history of the area and how I have interpreted this in drawing sketches and film projects. She has created a fab visual counterpoint to my musings and the film can be viewed on MyStreet. I will also feature it as part of a film programme I'm curating at the Louise Blouin Foundation & Portobello Film Festival during September 2013.

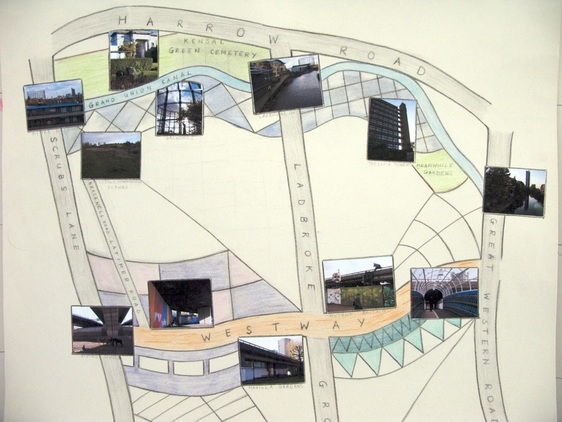

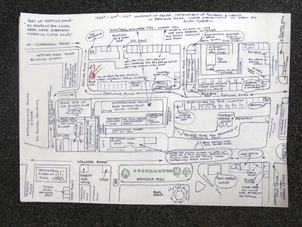

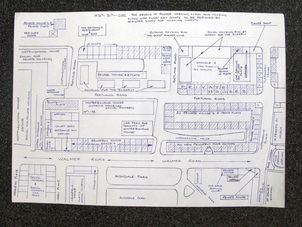

Took part in a HISTORYtalk event last night with Natalie Marr and Emily Ballard from Latymer Projects. I screened two short films called Flood Light (2010) and Home (2012). Also a selection of images culled from my archive research into the Grand Union Canal, Westway, Slum Clearance Programme and Silchester Estate development. This was a good opportunity for me to review my practice and to talk about maps created as part of my work. The first map, West London Waterways, was made in 2009 as part of a development bursary for the Cultural Olympiad. This got me noticed by the Arts Officer in RBKC and I was commissioned to stage an arts event as part of InTRANSIT 2010. Flood Light was a participatory film making project getting local residents and Londoners to connect with the inter-related legacy of the Grand Union Canal and Westway (A40). Naturally, I made a map and invited people to creatively journey across this landscape. Ten other film makers took up the challenge and produced excellent films. I was able to present this at the Portobello Film Festival alongside my own work. As a follow-up project, Home is about the last house demolished for the Westway. It's based on an evocative photograph taken by Mary Miller in the late 1960s. For several months I've been obsessively trying to find out more about this lost house and the home owner who refused to be moved as the wider area was demolished for slum clearance and Westway road building. No luck so far. I have microfiche disorder. At this juncture in time, I'm working with Latymer projects editing analogue and digital maps. We want to focus on the area around Bramley Road, Freston Road and the Silchester Estate in W10. This is an area steeped in radical history: 1958 race riot, Westway activism and Frestonia. It is also about to undergo regeneration (again) and our map will hopefully represent issues around community and housing. Check out the excellent map (below) made by Allan Tyrrell. For a full low down, visit the Latymer Mapping project website.  West London Waterways map, 2009. Inspiration for my eco-arts projects based around blue and green spaces in West London.  Last house demolished for the Westway, late 1960s. Photo by Mary Miller. © RBKC Local Studies and Archive. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed