|

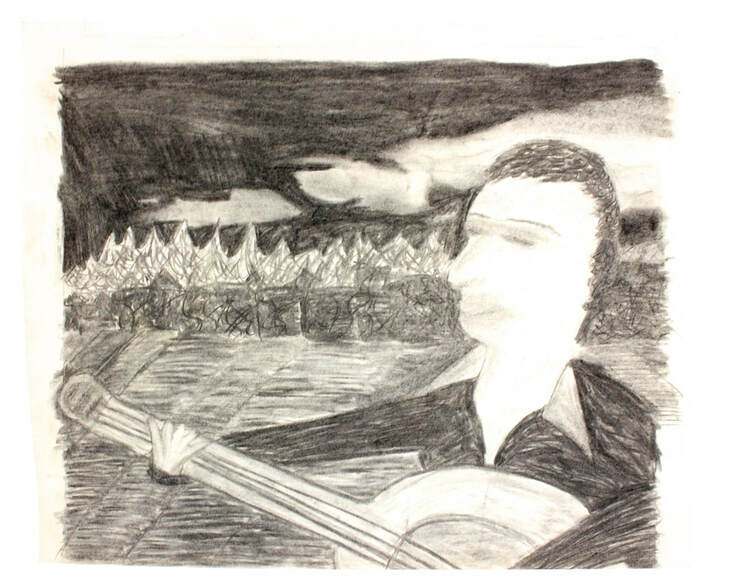

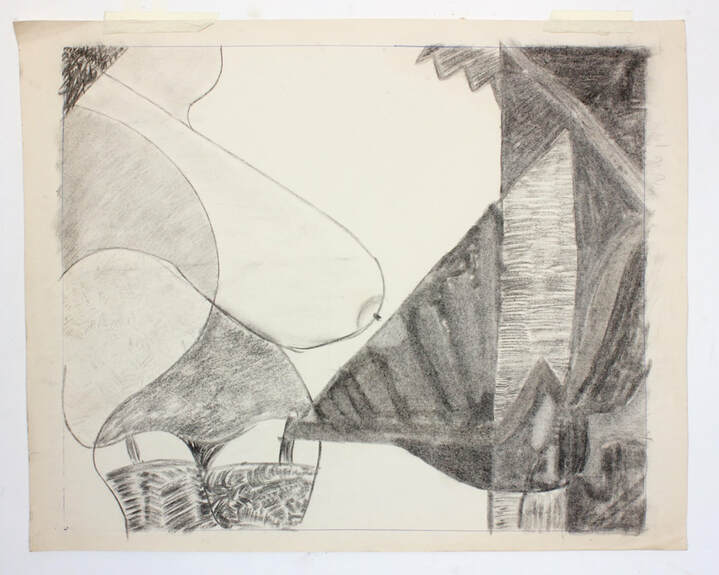

The Metamorphosis of Vine to Wine Charcoal, 78" x 57" 2019 "Three bowls do I mix for the temperate: one to health, which they empty first; the second to love and pleasure; the third to sleep. When this bowl is drunk up, wise guests go home. The fourth bowl is ours no longer, but belongs to violence; the fifth to uproar; the sixth to drunken revel; the seventh to black eyes; the eighth is the policeman's; the ninth belongs to biliousness; and the tenth to madness and the hurling of furniture." From the play Semele or Dionysus by Eubulus, c. 375 BC I never knew my grandfather, on the Greek side, but am named after him, Constantinos; His nickname on the island was Barba Chedeli. He cleared all the stones from the valley to grow crops that were sold at the market. Built his own house, furnace and wine press where grapes were crushed underfoot. Drinking in moderation, but enough to loosen the poetics of song and dance. In the face of war and famine, he was quite simply, glass half full. I thought I knew my father, a Pole. But he could never talk about the war and famine that exiled him to England. Vodka was never enough to loosen the poetics of song and dance. He loved me but I don't know if he was ever truly contented. No words in any language could quench his half-empty thirst. The mist drifts down the vineyard and into the corridors of the mind. This is the story of four bowls plus one and four. Drinking rituals executed with no particular rhyme or reason, beginning or end. An Existential compulsion. Top, left to right: Ruin of house built by Konstantinos Christofis, oven and wine press Bottom: Valley of rocks cleared for cultivation of crops, Oinousses Musical refugee as the city of Smyrna burns 24x20" charcoal 2009 A cafe in Smyrna where a Greek lad brazenly sings about killing and raping the enemy; And as he staggers home, drunk, after closing hours, a knife is plunged into his stomach. He dies in the arms of his sister asking for a glass of water. The heavens finally open to provide relief to the unseasonal temperatures. The family are sharing a heady brew, performing the last rites with a night vigil. Tomorrow they will gather their strength to bury the elder. But the stomach of the corpse starts to rumble and the children laugh, contagiously. They and the dead have not eaten any food in three days. The radio broadcasts convey the indifference and desperation of the phoney war. The family decide to bury their prized possessions, including a crate of wine, Little suspecting that the Nazi's will plant a colony of new forests on their land; At the same time, neighbours are either executed, or forced to wear a yellow triangle on their back.  Bound and gagged 23x19" Charcoal 2010 The student on the Intercity 125 has a Cold-War identity crisis. Tucked in the breast pocket of his 1940s herringbone overcoat is a 50ml bottle of Glenfiddich And a notebook of Ted Hughes-inspired poetry written under the pseudonym of Marian Evans. The wonders of a comprehensive education and full-maintenance grants; With enough left-over change in the other pocket to fund decadent posturing. Thatcherism hasn't fully fucked up or revolutionised the country, yet. Every time she cooked a meal, pasta alla wild fungi, cooked in red wine, Trying to worm her way to his heart through the stomach: His stomach ached and gassed for several hours, kiss by kiss. Lilac Wine by Jeff Buckley was playing in the background. There is a lone child in the other room of the flat and it is hungry. With bottles scattered behind pot plants, cans crushed under sofa cushions, She has had too much to drink and vomits up a meal of alphabet vegetable soup. And now still retching, trying to divine the significance of letters in the sink...G...M...T.... Suspense with suspenders 24x20" Charcoal 2009 It's a hen cruising night at Camden, three over the clock. Sat on the edge of a kerb stone, dress semi-hoisted, bladder overflowing, She wants to leave her piss stain for all the zombies in town. England have been knocked out of the World Cup. Then. Commotion. Club-crawlers are alarmed. But as her eyes refocus, there is a female death-metal band running down the street. She laughs at this godforsaken photoshoot and dribbles more pee. Instinctively. Fingers. Instagram. He has a name in the art world for creative notoriety in the manner of Francis Bacon: Violently bragging about who dares wins, fuelled by drink more harmful than cocaine and heroin. Not to be outdone, his partner has left him for an Amsterdam retreat. They are cursed to fantasise about each other in hangover and high mushrooming cloud. The cuts and bruises still fresh on their respective bodies. There is a trade war between China and America. Tree as a thorn in my eye (Set design after Wojciech Has's Saragossa Manuscript) 23x19" Charcoal 2010 Donning hat and coat and slipping on dancing shoes. Le freak, c'est chic or is it the Can-Can? His or her mind is shifting in time and place. And this is the first time you fully recognise a problem with hearing and balance. All those drunken conversations and couplings, fading to static and then silence. The flesh, still willing, spinning you on the dance floor; until the world falls from grace. Your life was foretold in the opening sequence of the film, Le Plasir (1952), Where a masked young dandy celebrates life on the dance floor, then collapses. How is that possible? Perhaps, if we cut out the liver and rip-off the facial mask, Everything in the spurting toxic blood will be revealed as both ancient and Science-Fiction. L-R: Three generations: Konstantinos, Constantine and Kazimierz Gras

0 Comments

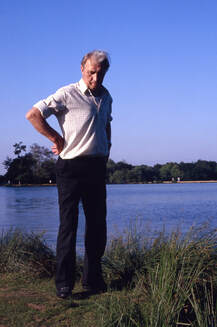

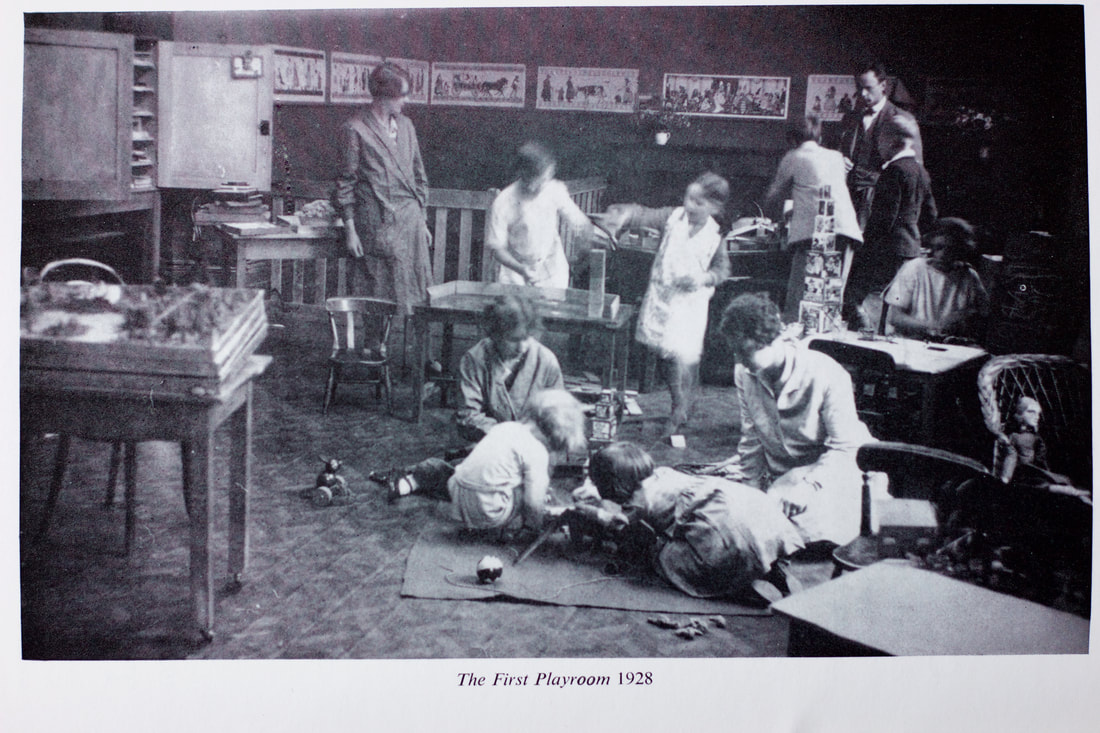

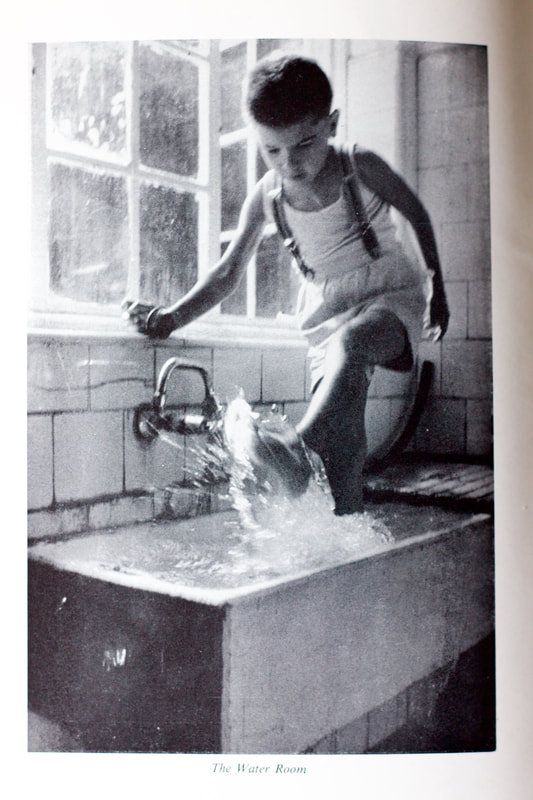

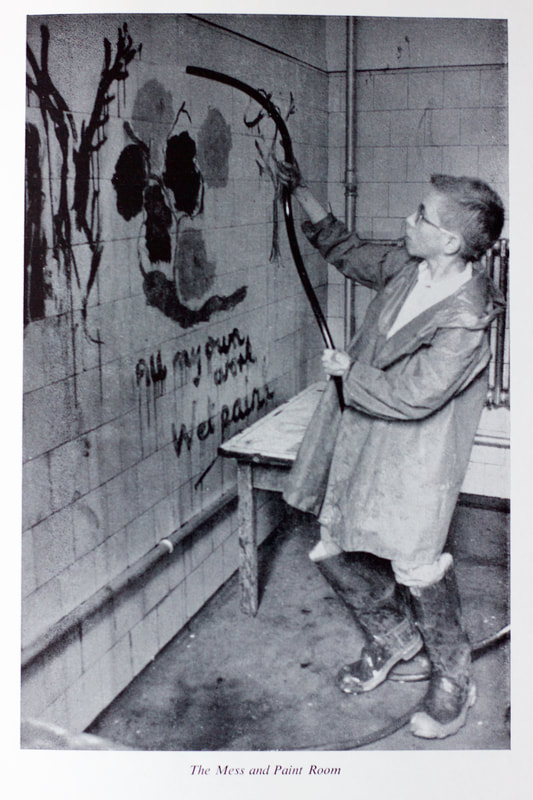

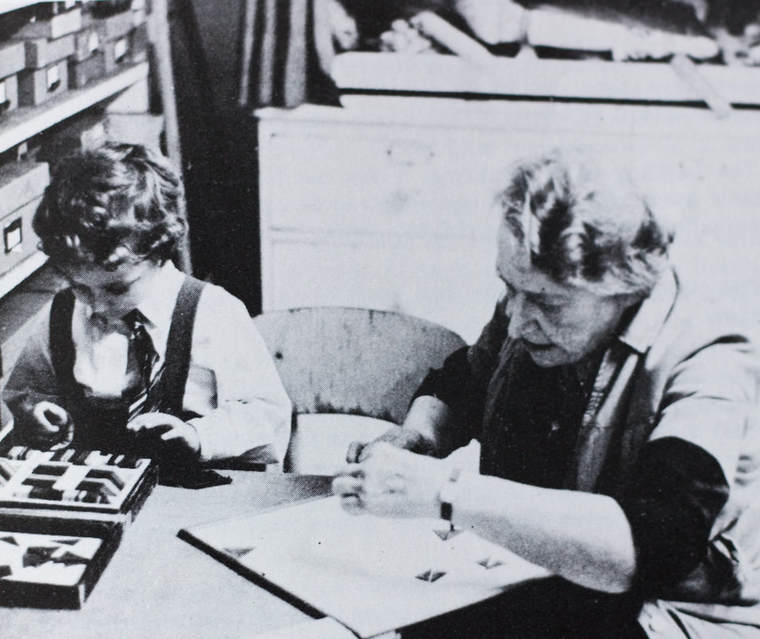

Margaret Lowenfeld (1890-1973) was a pioneer of child psychology and play therapy. She was able to make creative connections of the highest originality. The child-centred philosophy she developed and its process of therapeutic play-making was the culmination of many factors: central to these being her experience of children traumatised by World War One; and also her observation of the colourful patterns in Polish folk costumes. Her work and legacy has influenced my thinking and art practice, both before and after the Grenfell Tower fire that occurred on 14th June 2017. I have always used a model of art making that was rooted in play and non-verbal processes of communication. I was able to use this during Art for Silchester, a seven month residency that has just ended at Silchester Estate. I worked with residents and children who live across the road from the tower and each of whom are coping with the tragedy in different ways. During these sessions, we made large scale drawings and ceramics which were indirectly connected with the therapy of Margaret Lowenfeld, who first started her work in this area of North Kensington in the late 1920s. I also recently met up with Margaret Lowenfeld's great nephew, Oliver Wright, who is one of the therapists working with the NHS in providing support to local residents traumatised by the fire. But this blog is an interview with Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock that was recorded from July-Sept 2018. She is retired from practice, but was trained at The Institute of Child Psychology in the early 1970s and was the leading proponent of Lowenfeld Mosaics as applied to child psychotherapy. In talking about her life and work as a Lowenfeld therapist, I was also able to open up and have a reflective space to think about my own feelings, my inability to voice them over the past year and how I am now moving forward as a person and artist. A war child in Hong Kong and China I was born in Hong Kong, a British colony in 1935. My parents were both teachers. When they graduated from university they started their own school based on my mother’s ideas. She was an intuitive teacher and had this notion that when you teach a child it isn’t just the teaching that counts. It is also about the child. In Hong Kong during the 1920s and 30s that was a rather unusual idea. When the Japanese took over Hong Kong they changed all aspects of our lives including our consciousness. When my brother was born, my parents decided they didn’t want to live under the Japanese and they went to Canton, China. We had nothing and squatted in an empty house. My parents had to have two jobs in order to have enough money to feed us. I was left on my own and wandered around quite a bit. I once stumbled across this march. Being small and very inquisitive I wiggled to the front. There were two Chinese men being executed by the Japanese. The whole crowd watching was Chinese. As soon as one of the prisoners stepped forward the crowd cheered. Then a band of soldiers tried to shoot him but he kept on spinning and it took a long time for him to fall. The crowd just kept on cheering. I was an innocent child and didn’t know anything about politics, but I thought: fate was going to show the people this was a good man. Children see things that they don’t understand and they have to make some sense of it. I didn’t see him fall and I thought he was a good man. That thought came to me as a child and I only found a word for it, patriot, when I came to England. So the words come much later in my understanding. After some time my father returned to Hong Kong to see when it would be safe for the family to return; leaving my mother, my baby brother and myself in Canton. It was during that period that I met a Japanese boy. The meeting was very curious because the Japanese boy was trained to think that Chinese natives were bad. I was walking with my brother in my arms and he threw a stone at me. It hit my elbow and I got really angry. I rushed home, dumped my brother on the bed and went back. I said you hit me and I’m going to hit you back. It was very foolish of me because I was eight and very tiny. He was about ten or eleven. He was so shocked because I could speak Japanese. He then said: if you can speak Japanese, you must be educated and civilised. So he wouldn’t fight me. We became friends and I learnt even more Japanese from him because I didn’t have anyone else to play with. My mother knew nothing about this Japanese boy because she was so busy earning our rice. Just meeting him prevented me from thinking that all Japanese were bad. This later fed into my understanding that all group prejudices were a generalisation of personal experiences. Life is not simple. It’s not reasonable. It is not governed by things like - if this happened here, then that happens there. There is a war, but for the individual child all kinds of experiences are possible. These were war-time relationships and had no consequence afterwards. But even now, I sometimes wonder what happened to that Japanese boy. A scrambled education and life in post-war England We came back to Hong Kong in about 1946 with a wheeled cart and the little luggage we had. My father had found a flat. I continued to look after my brother but not for long. My mother wanted me to go to school, but I had missed three years and so my Chinese wasn’t up to standard. So she decided to put me into a school where the teaching was in English. I didn't know any English. I was 11 and had to spend the first few months writing nothing but lines: I MUST HAND IN MY HOMEWORK. I was always semi-bottom of the class. In my school leaving year, I failed in everything because I couldn’t be bothered to study. It just seemed too difficult. My mother asked me if I would be happy to be a street sweeper or a secretary. It was then that I realised the value of an education that enabled the individual to have a wider choice in adult life. So that year I started to study. When the exam results came out they would be published in newspapers and the top 50 students would get scholarships. I got one. That was such a shock. I later discovered that my mother had been saving money for my education. But my father would always say - don’t overeducate your daughter because she won’t get a husband. You can see there were two very different philosophies in the household. But in the end he was very proud of me. At university I knew I had to study hard. I studied political philosophy. I did psychology, I did logic. All the kinds of things you don’t get at school. Wonderful. I was just enjoying my life. I wanted to become a librarian because I love books. The only post-graduate course on librarianship in the whole of the UK was at University College, London. They had lots of foreign students but they only accepted people with First or Upper Second Class honours degrees. I was very lucky to get in. They said do you have a classical language? I was very cheeky and said I have Chinese. I didn’t tell them that I only studied basic Chinese. They said, they didn’t have a Chinese student and we’ll take you even if you haven’t got any Latin or Greek, nor German or French. This must have been in 1958 and it was a one year intensive course. During the second term I had pneumonia. I was staying in a university hostel and the registrar who was looking after me thankfully had a nursing background. When I went to take the exam, there was no way I could pass it. I passed one paper. I failed the other. They said we really want you to pass, so come back. But I had no money and the course was teaching you how to catalogue Latin manuscripts for working in a university library. It was not for public libraries. I thought this is all too alien and that I couldn’t continue. Domestic life and the discovery of a vocation I then thought I might enjoy teaching but got married and had children. I had to learn how to be a housewife and mother in England. All without any help. What I discovered was that I could talk to another PHD person but I didn’t have any ordinary language. My husband was working in the Midlands as a salesman and he travelled all over the place. We were living in a new estate which had just been built and I didn’t know anybody there. The biggest town was Bromsgrove and that was at least three miles away. We had no telephone. My husband just thought: this is your domestic scene and he decided to have a mistress. I said, this isn’t right, is it? We can’t carry on together when there’s no connection. So I was in a terrible bind and came back down to London. Then he followed with the children. I had to get a job. As I was the one who left, I had to help with the family finances and earn enough so that my husband could have some of my earnings as well. Then I met Jasper. We discovered that maybe we should get together. Jasper and I were married for 46 years and the children lived with us. The children have always thought of him as their dad. During this period I also had personal therapy. The therapist said to me: I can see that you don’t want to be a librarian anymore or a teacher. Do you have any ideas? I said: yes, I want to sit in that chair (pointing at her). I’m going to be a therapist who sees children. First Mosaic made by Therese upon arrival at the ICP, 1969 The Institute of Child Psychology (ICP) I went to Hampstead to visit the Tavistock Clinic. They said you can’t see anybody because they are seeing children and they are in private practice. I said: how do I find out about your training? Well, you’ve got to come to attend our courses. How long will this take? The lady said: it depends on the individual but it could be 4 or 5 years and the student would need to have personal psychoanalysis as part of the training. I just didn’t have the time or money for this. So then I went to visit the Institute of Child Psychology in Notting Hill and they said: Dr Lowenfeld will see you, but she’s with someone else at the moment. They gave me a Mosaic to play with while I was waiting. It was a very clever idea. I knew nothing about what I was doing. It was fun. I made this tree and plane in my Mosaic. In hindsight, I realised this encapsulated my journey and life here in England. The tree was me growing up and the potential to develop in this country through the course. What I didn’t know was that they kept records of all Mosaics and when the Institute closed, I looked through the records and rescued my Mosaic. Margaret Lowenfeld was one of the first child psychiatrists who was interested in finding ways for children to express themselves without only using words. She thought about what happens to a child between age zero and seven. How do children of that age think? She realised that what children perceive is multi-dimensional and cannot be put into words that are in linear time. The child has many ways of seeing the world and they formulate ideas through their sensorial experience. Lowenfeld had this notion that they do it through pictures. So she had this idea of picture thinking in the late 1920s and 30’s and pioneered the use of Mosaics and the World Technique; the latter known more generally as the sand tray used with miniature toys in dry or wet sand. These are play and language tools for the children to express themselves without relying solely on words. Lowenfeld opened the Children's Clinic for the Treatment and Study of Nervous and Difficult Children in North Kensington in 1928. This offered a unique form of therapy for children that did not exist anywhere else in the country. Before the Second World War, the clinic was very well known and mainly supported by private funds. Lowenfeld wasn't charging the local people very much because this was a poor area and she wanted these children to have the use of these facilities. Photographs of Margaret Lowenfeld and children using the World and Mosaic. There was a change of name and The Institute of Child Psychology relocated to 6 Pembridge Villas in Notting Hill Gate. The Institute had facilities that were exclusively given over to the self-generated play activities of children. There was a big basement to the house where the playrooms were located. The children could play ball and use climbing frames. There was a trunk on wheels which the children could hide in. Another trunk had clothes and hats and objects. This was used for dressing up and often lead to dramatic play in innovative ways. There was also a painting room where the children could paint on the walls. You could hose off the paint with water to obliterate the child’s painting should the child not wish for the painting to be kept. There was also a water room where you could have water and toys on the floor and we all had to wear waterproof clothing and wellingtons. The older teenagers might think that playing was too childish and so they could talk in what we called the Quiet Room. Occasionally we would take a Mosaic in for them to use. The Institute always had a file for each child’s therapy work that included a recorded copy of all their Worlds, Mosaics, drawings and paintings. At any given time you might have 6 therapists with their children in the playrooms. We worked together as a team, often helping out by observing other children when the therapist might have missed out on some aspect of their child’s action. It was also a very demanding training. I could write about 12 pages of notes that documented what my child did in any given session. We would never impose a point of view or interpretation of their play. The aim of all this was to allow the child to express their point of view and feelings through play. I started my post graduate course in 1969 and this lasted three years. We only had two new students per year. We had daily supervision, but on Tuesdays and Fridays we had two hours of group supervision to discuss what we called Corporate Cases; these were the children who were not solely the patient of a particular therapist. In the student’s last year, they would be supervised by Lowenfeld. I liked doing the Mosaic and the World with the children. It could take two sessions to do this because sometimes children take forty minutes to do a Mosaic. I prefer to use the Mosaic because they have a progression or a regression and they tend to be linear. I don’t interpret the mosaics. I talk to the children through it and then sometimes they will tell me what it means. The Lowenfeld therapist always had to be lower than the child. I would sit in a chair that is the same size as the child. I’m lucky because I am fairly small anyway. Lowenfeld was not psychoanalytical. She said her ideas were only just one philosophy and so we were taught about Freud, Klein and Jung. She said you will need to understand what other professionals might tell you about the child under consideration. The Institute had a child psychiatrist, an educational psychologist, a social worker and a West Indian social worker, as the area the ICP was in had a lot of West Indians. I think I had an excellent training and it never troubled me that the psychoanalysts thought I was not trained. Lowenfeld had set up a proper postgraduate institution and awarded postgraduate diplomas. They had an academic board who oversaw standards. That’s why I got a student grant because it was properly recognised by the national Education Department. Case studies and sexual abuse I remember this nine or ten year old girl who came to the Institute and just stood rigidly. She believed that her back was made up of one bone and that she couldn’t bend her body. She only spoke in whispers, not wanting to expend her energy reserves. She was worried that she would die and had stopped eating. I said to her: do you know what our back is made up of? She said there’s a bone there. I said your quite right but there’s not just one bone but many bones. I’ll show you. We had these models. I got her the skeleton and I went slowly down the spine guiding her hand so she could feel the knobs. The first treatment objective was to get her to learn about moving freely. We often did body work because, for instance, many girls didn’t understand about menstruation. There was also a fifteen year old Indian girl who was very unhappy and wasn’t eating. She told me she was going to have an arranged marriage but wanted to go to university. The parents felt that any further education would be unnecessary since their aim was for their daughter to get married immediately after leaving school. To enable her to get into university, I said: you have to go to the library rather than home to do your school work. Sometimes therapy is being pragmatic for people to get out of these difficult situations. You’ve got to offer them a solution that will relieve them from that. Only then can it be analysed and if the child wants it to be. What happens if the daughter is expected to sleep with the parents? I said okay. Which side of the bed are you sleeping? I’m sleeping on the right hand side. Who else is in the bed? Mummy is on the other side. So I asked who is in the middle. That’s daddy. I asked her how she liked the arrangement. This is a thirteen year old girl and was a case of sexual abuse. There are girls who I can discover their issues through their World Play or like that girl who did a Mosaic. She kept on shoving Mosaic pieces in between other pieces. I said sometimes that happens to older people as well. She nodded. I said: it also happens to girls. What you need to do, to stop this, is to tell an adult. There’s a law that allows me to talk to you about this. I was getting somewhere with one child who was telling me the parents were abusing her. The parents then stopped her coming to see me, saying Mrs Woodcock’s English is so poor that my child can’t understand her. You can’t argue with that. What I said to the girl was: I’m sorry this is your last session because your parents are not happy about you coming. I said: you know what the problem is. You are fifteen and by the time you are sixteen, you can leave home. That was all I could say. Perhaps there are limits to the therapeutic process. Lowenfeld never talked about sexual abuse at all. You would think she never knew about it. But you see nobody was talking about it at the time. The biggest change I saw over these years was actually having abuse recognised and also the legal aspect of myself and social workers having to report it. I thought that helped me to talk to the children. By law, I had to report this and some other professionals were then able to help the child. In Summary I am extremely grateful to have attended the course at the Institute of Child Psychology. It enabled me to help children by using the World Technique and the Lowenfeld Mosaics. When I graduated in 1972, I worked for the NHS and child guidance clinics in Newham, Haringey and Barnet. Both Haringey and Newham were multicultural and deprived areas. I didn’t actually want to work anywhere else. That was a personal choice. I wanted to work with a variety of children including the poorest. I saw my last case in January 1995 having worked as a Lowenfeld therapist for over 20 years. A selection of my work will be housed at the Wellcome Library as part of the Margaret Lowenfeld archive. Expressing the shape and colour of personality: Using Lowenfeld Mosaics in Psychotherapy and Cross-Cultural Research By Therese Mei-Yau Woodcock, Sussex Academic Press, 2006. Photographs and text kindly reproduced: © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library. Postscript Let us end with Margaret Lowenfeld's account of the first day the Clinic opened on Telford Street in 1928. This was in rooms hired from the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre (aka birth control clinic) where Margaret's sister, Helena Wright, worked as the Chief Medical Officer: The two rooms that allowed for the Clinic's work consisted of one opening direct on to the street, which we used as treatment room for the children, and a second room opening out of it. Here records could be made and kept, parents interviewed, biomedical investigations carried out and discussions conveniently held between myself and my colleague. Money was short so the playroom furniture began as one table and three chairs, one of them a fireside chair placed between the diminutive gas fire grate. The play material was kept in the second room and carefully selected for each child who came - it was too precious to be indiscriminately displayed. Later a second table was added for the children to paint on, the first round table remaining in the centre of the room. A scene in which this table figured later won us our crucial friend. The first child who came was the "bad boy" of the neighbourhood, abominated by the shopkeepers. He came by himself and I do not remember seeing his mother. He was defiant and silent but remembering the Polish children, I left a French painting book - these were lovely (good ones being practically unobtainable in England) on the table with water and painting brushes. He seated himself with his back to the centre of the room and studied them. Half an hour later I stood silently in the communicating door watching him. His concentration was intense, he breathed excitedly and - schools being different in those days - I found later this was the first time he had the magic of colour in his hands. Every day the Clinic was open he came, and slowly began to talk. By that time I knew his attendance at school was erratic and all efforts to improve this had been defeated by his silence under questioning. We made a pact together: more regular attendance at school on the days and times the Clinic was not open, and fresh paints and painting books when he came. It was from the school we heard later that a different boy had slowly emerged - complaints against him ceased. One day he brought a young friend with him and we knew we were winning our way in the neighbourhood. Constantine Gras making a mosaic, with from left to right: red beacon, tower from black to green to no colour; myself draped in those colours; and a key, a set of arrows pointing to me, the tower and Thérèsa as witness to the mosaic. "I felt I needed something in addition to the tower and me. I don't know what it is. Maybe it's a signpost trying to direct me or others, but everything is shifting apart again over time. Then I step back and look beyond the tower and me. I want to get a sense of the overall space and how these objects function within that space. Can I possibly create something that is aesthetically or emotionally satisfying? I am trying to make a work of art. I'm not sure if that is right." "Yes. You are an artist. You cannot escape that." "I was hoping that I might, but I don't think so." "You won't be able to escape yourself, will you!" "No. No." At Play In The Ruins: A Lost Generation

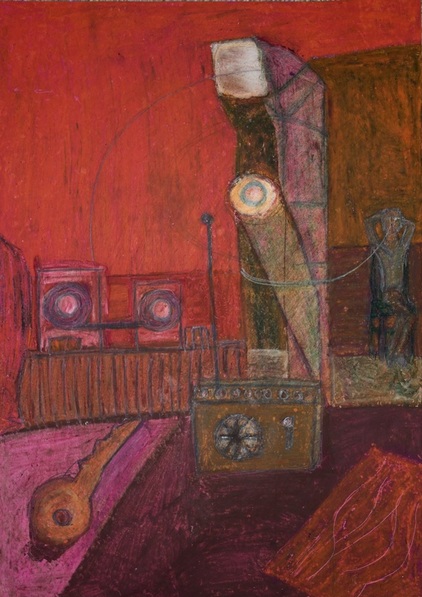

oil pastels, 33x24" 19 Dec 2016 Artist's comments on the reverse of the drawing: Starting off with abstraction, but thoughts turned to Lowenfeld sand play (Sand Face in the picture) and childhood. The news on the following day. The battle and now the desperate evacuation of Aleppo in Syria. One of the defining media images of the year, Osman Daqneesh pulled from the bombed building. His haunting stillness in the midst of horror. What would you do? Imagine your neighbour Heinrich Boll had left you a spare key and instruction to water the house plants while he boarded an aeroplane to collect a Nobel prize. Would you steal inspiration from the draft in his typewriter? Or Max Opuls had entrusted you, his dear friend, to retrieve a roll of film from his house; the one the censors didn't see in La Ronde. Would you leer at the said negative being held up to a bright light source? Kathe Kollwitz had to nip out to buy some milk and bread. Mischievous thought of adding a smiley face of ink to the desolate image in the printing press? The aforesaid fantasies were inspired after listening to an interview Holgar Czukay gave in the early 1990s on the Radio 3 programme, Mixing It. He recounted how as a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1968, he sweet talked the secretary and gained access to Herr Aladdin's electronic cave. Holgar was able to record his debut album, Canaxis 5, with the studios impressive tape recorders looping together his interest in Musique Concrete and ethnographic folk recordings. Not all studios live up to their profession. In point of fact, given the relative poverty of artists, they invariably have to beg a shed, borrow a broom cupboard or steal a loft. I have only had one bonafide studio. This was once a 1960s council flat (bedroom, living room and a kitchen) and came with the responsibility to practice community art. An author might build a studio around the typewriter on an heir loomed desk or a poet might dream on a hammock in the garden. Maybe virtual studios will one day be the norm for web based artists. The creation of an avatar, perhaps even adopting the identity of the Germanic artists I have already listed. Expanding on this chain of thought -what about that elusive key to the artist's mind?

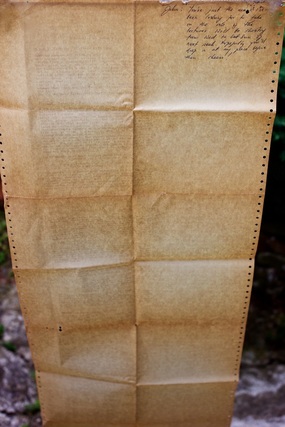

Script for This-That by Jacob Barua. Printed on continuous feed paper, Warwick University science block.

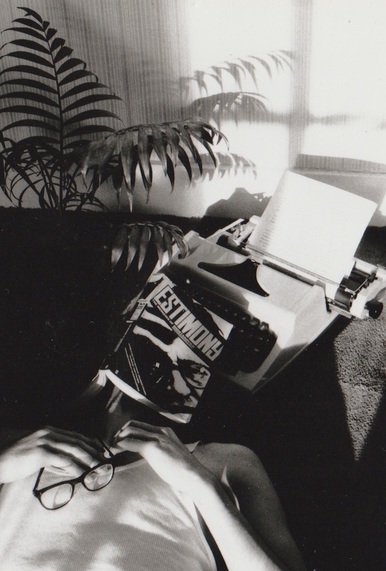

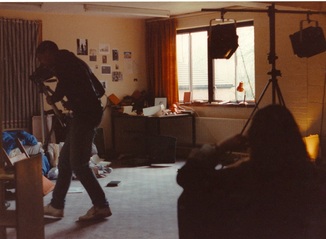

I am navigating back to 1989 and the University of Warwick. My fellow Film and Literature student, Jacob Barua, has handed me a film script and declared emphatically: you are the only person in the universe who can play this! I hesitated. Had never acted before. And then there was the troubled central character in the drama who seemed all too recognisable; forever on the edge of everything, nothing, relationships, art, politics. This begged the following question: Jacob are you taking the piss out of me or yourself? For a short period of time we seemed to swap identities. Jacob’s intense cinematic vision became one with my suited and booted persona. Jacob was going to use this short film to catapult him into the prestigious Lodz film school. But it was no plain sailing. No film production on this dramatic scale had been undertaken at the university where theory ruled the day. It meant sniffing out equipment and resources. After two weeks of filming, a mere two days were spend in the edit suite, using equipment for the very first time. I recall a few expletives. We had set the date of screening, one day after the final day of editing. A key animation sequence shot on 8 mm film only arrived on the day of the screening and had to be added post-haste, post end-credits. Thankfully this has now been re-edited into its proper place in the dreaming body of the film. We finally have the keys to the digital edit suite. It's only now after 26 years and working together again on restoring the fading VHS tapes, that we’ve got a new grasp on the importance of this film for us. Let me leave the final words to Jacob Baura who was recently interviewed about his Warwick experience. What on heaven or hell was he thinking about when he made This-That?

Jacob Barua:

"The reason I wanted to become a filmmaker, did not have that much to do with film per se. I had always been enthralled by Art itself in all it's aspects. I had been a poet, a musician, a painter, photographer, amateur actor, but probably loved literature most of all. Somewhat like a brat with his hand in a jar full of goodies, I did not want to let go of any of the Arts and decided that there was was only one vessel that encompassed all of them. The only way, in which I did not have to discard any, but instead fuse them, was through the glowing medium of film. I arrived in Warwick...by mistake. One of my obsessions when it comes to the written word is History. Right until today I often wonder whether I am a self made historian expressing myself and researching through film. Warwick conjured in my mind the mystery and glory of medieval times. I was convinced that the University of Warwick was located somewhere within the town of Warwick. In those pre-internet days, a major source of information were brochures. And the university's were filled with images of Warwick Castle and the old cobble stone streets. That was enough for me to decide, given that it was simultaneously the only university offering such a broad course encompassing foremost literature and then film. I got off the train in the quaint railway station only to be horrifyingly informed that the university was far away in some fields between Coventry, Leamington Spa and Kenilworth! I found the course at the university to be exhilirating in it's scope - exactly tailored to my needs. Great lecturers and given the small size of our department, an opportunity to bond with colleagues. The university also happened to probably have the largest independent Art Centre outside London, at the time. There was everything ranging from a philharmonic orchestra to to a cinema with plush seats and a sterling screen, to one of the best equipped professional theaters anywhere in England. Here I was active as a member of the Warwick Drama Society, taking on delicious roles for the duration of my studies. Besides, the university was a beehive of political activity, of all manner of shades. Of course I was aghast that the most prominent ones were for naive fellow travellers of all manner of totalitarian off shots. However the jewel of this mini-city was a massive library, with a salivating wealth of books that was beyond belief. This-That was the result of a deep inner need to encompass my entire experience as a student who had lived in different countries, cultural and political systems. At the same time I set to creating a time capsule to be sent into the future. All Myths were after all created by somebody, even if that was thousands of years back - so why not make one too, there and then, to be flung into an unfathomable distance? My inspiration for the main character was essential to creating a core, and this was based, at least in terms of the visuals on a readily available 'blueprint'. For I used Warwick's most enigmatic and unique real life student - Constantine Gras. He did not fit into any preconception - as he neither had the persona of a typical student, nor even one from any 'civilian' from our contemporary milieu. Here was Someone who seemed to have been historically misplaced, from a 'wrong' age. Like a potter I used him as my clay, to impose onto him a narrative, which I knew would jar when combined with his persona. So here was a man creating himself i.e. Constantine, whom in turn I was creating further. Layers of creation. One of the overarching themes is the struggle that each human has to undertake to find a space of comfort, to be able to be oneself, while struggling against the dominant societal forces. By comfort I do not at all refer to a personal one, but that of the Other. For the most crucial single question ever spoken for me, which forever thunders across all ages is; "Am I my brother's keeper?" We live in a world circumscribed by political correctness. The moment you challenge the narrative of the day, you are deemed fit for condemnation and rejection. In the case of the film, the character not only isn't ascribing to Modernity and the race to keep up with fashions both external and internal, but occupies a realm that defies the obligatory 'standards'. He is still both a reflection of the Ancient, Romantic and Future ages. Whether we like it or not from the beginnings of History, politics impinge on almost everything in life. That is why the culmination of the film is congealed within the incongruous figure of a young pyjama clad student who dares to take on the Rulers of the World. The selfish manipulators - the Daeduluses vs the selfless dreamers - the Icuruses. If I were to try to draw a circle; Sleep - Pyjama - Dream - the Impossible - Courage - Death - Eternity - Sleep.

The reception of the film, I will admit, was heart breaking. An outright regurgitating by the audience. Particularly so - when not even our lecturers or collegues could grasp or extract any meaning out of it. But this should have been expected, as it was intentionally put together in such a way as to defy conventional modes of film-making. And again, it was indeed a film made for Another age. But which one? Time will still tell.

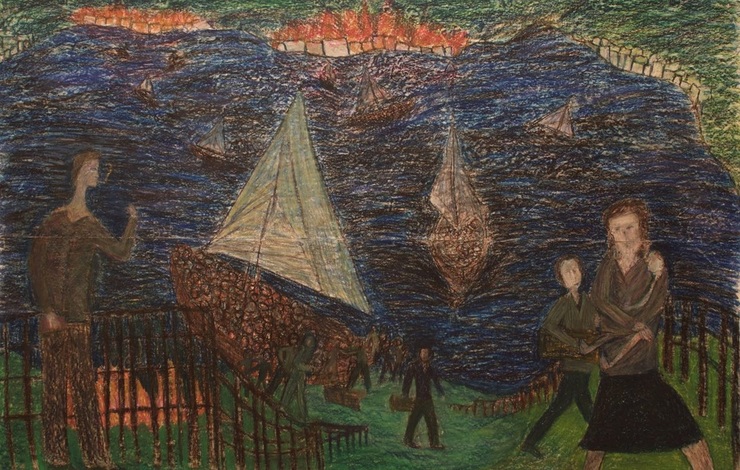

I have no regrets about the film as it was then, and in it's curent slightly re-edited form. It turned out prescient. You are Alone among people. To be fulfilled you have to metaphorically fly, even if demise is the price to be paid. There is no escaping Newton's and other more serious Laws. But just like there was no relevant message in the film for the audience at the time, there similarly isn't any for those today. There are plenty of other better sources, dear audience member, if you are in need of a message. This is not a cerebral feast but mainly a sensory experience. Once I got there, one of the most satisfying experiences at the Lodz Film School was when all students were herded into a cinema, and made to watch the film by Piotr Wojciechowski; he was a Filmmaker, Scriptwriter, Catholic Philosopher but most of all a living legend as a novel writer ("Skull within a skull", "Is it worth to have a Soul" and others). He immediately took to the film. In his laudatory lecture after the film, he said he felt it had the feel of T.S. Elliot's " The Waste Land". He was the first ever viewer to fully comprehend the ambitions of this film. At the Lodz Film School I carried on with the 'tradition' of making This-Thatian films. With no pretence at all. Poland's greatest ever fimmaker, and it's Chancellor Wojciech Has, would always chide other lecturers for being baffled by my films - telling them that they were wrong to search for conventional meanings in my short films. For him they were "Intricate riddles" I don't really have any wise tips for aspiring filmmakers. Rather warnings, in that it is going to be a lonely, cruel, and ungrateful journey, except for the very, very lucky few. Well, take heart - at least there's going to be one worthwhile viewer of your creation - Yourself. Having been trained on 35mm makes a filmmaker by far more disciplined and honed to the workings of a film. The Digital Age has its own advantages. But the downsides are greater. More self indulgence and turning an important medium of Art into a toy. I have been a gardener for a long time now. There's at least one massive film within me waiting to happen. Then I intend to go back to my gardening. It's this and that, after all." If you want to experience This-That, the film is screening on: 10th September 2016 around 7.30pm Muse Gallery, 269 Portobello Road, W11, London Portobello Film Festival Full venue and programme details. This-That Trailer from Constantine Gras on Vimeo. It is with great sadness that I have just received news of the recent passing away of Victor F Perkins. He co-founded the film department at Warwick in 1978 and made a decisive contribution to the acceptance of film as an art form worthy of deep study. I have fond memories of him hunched over the Steenbeck undertaking a close textual analysis of In A Lonely Place with 2-3 students; a more kinetic Victor was found over at the Student Union playing his favourite pinball machine; delivering those impassioned lectures where he poured his intelligence into the vessel of a film; seeing so much nuance in terms of decor and edit, so much so, that I seem to recall, at the end of one lecture, Jacob asked: is it really possible that the film maker meant all this? Victor bough a copy of This-That in 1989 for the university archive. It was always a pleasure to meet up with him over the decades since I graduated. Alas he missed the screening of the remastered film at the university in March 2016, but I was touched when he specially came in to see me and we had a good chin wag about life: how he was adjusting after a recent stroke, his desire to learn the German language, his concern about the corporate development of education and his cluttered honorary office in the department which he really should tidy up. I told him that we had dedicated the film to our old lecturers who had inspired the young to fly. Victor had a rueful smile. To Μικρό ταξίδι To Micro Taxithi The small journey. This is the name scholars gave to the 8km journey across the azure stretch of Aegean sea From Anatolia, Asia-Minor, Turkey in-the-making A red-blooded journey once made from that landmass to the Greek island of Oinoussa. My family and other animals were empire builders, well versed in trading, seafaring. Of late they had settled into tilling the Ottoman soil and and selling crops to market. This bucolic existence prepared them not a jot for twentieth century war, famine, genocide. Forced to flee and cast out to sea, my grandparents made that small journey from Anatolia to Oinoussa in 1922 While over a million Greeks (not to mention Greek and Turkish muslims) were displaced from their ancient homeland. Modern refugees from Syria and other conflicted regions are making this self-same journey Across the Aegean to Oinoussa and the nearby islands of Chios and Lesbos. Where will their journey take them ? I am compelled to tell of another more expansive journey in 1943. The phoney war was dead real and my father limped on foot and by boat from Poland to England. He joined the Polish Free Army and armed with wings of freedom parachuted back into Europe Only to experience a bitter victory as Communism replaced Nazism. He joined the ranks of over 200,000 Poles who settled down for a new life in England. A small journey from Włocławek to London, boy to man, soldier to carpenter. Return back to the future on the island of Oinoussa. In 1959 my mother makes the painful decision to wave goodbye to her father for the last time. Her sister has already made the move and tempts her with dresses from Shepherds Bush market. Another journey is made by boat to the white cliffs of Dover and a sterling new world. A small journey from Oinoussa to London, girl to woman, servant to dinner-lady. While my father's earthly voyage has ended, the diaspora is beginning anew. Today more desperate migrations are being made by air, land and even under the English channel. Bodies are once again being washed ashore on the beaches of Oinoussa, Chios and Lesbos. Where will all these journeys take you? If one day you arrive on this fair isle of England, I will be there to welcome you. Kazimierz Gras Polish Parachute Brigade, 1945 Farewell party for Moshoula Christofis Oinoussa, 1959. The house my Grandfather built in 1922 on the island of Oinoussa The transmigration of Greek souls 16x12 " oil pastels 2003 The small journey across the Aegean

64x41 " oil pastels 2015 |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed