|

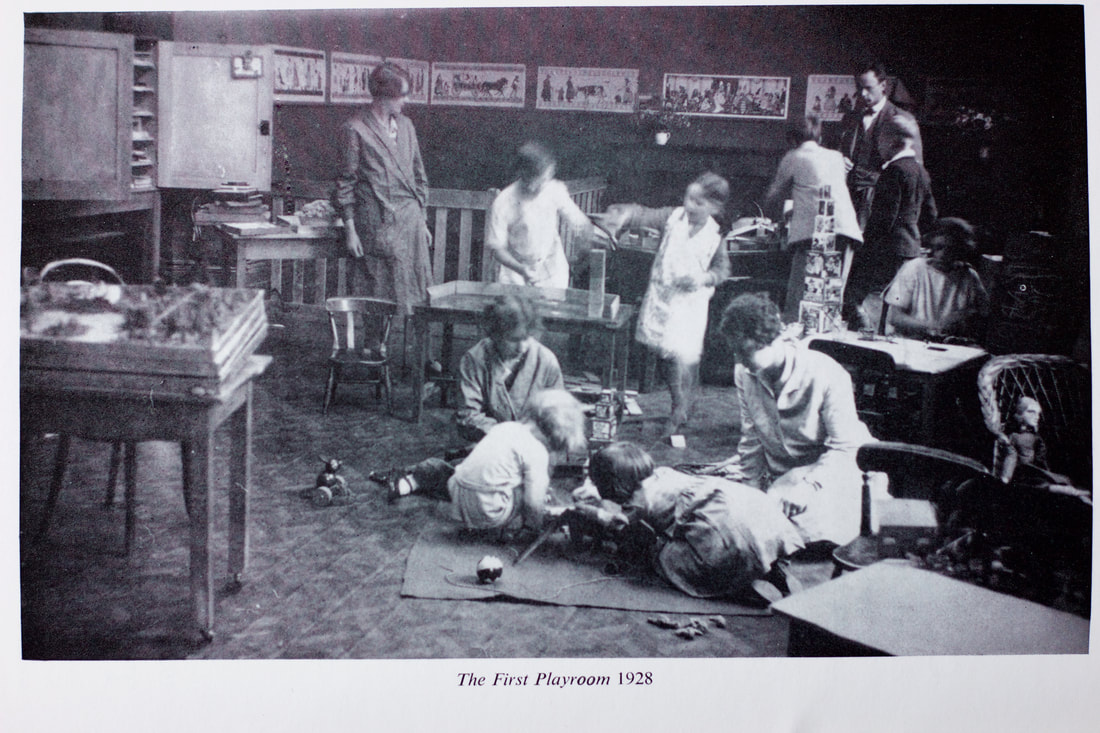

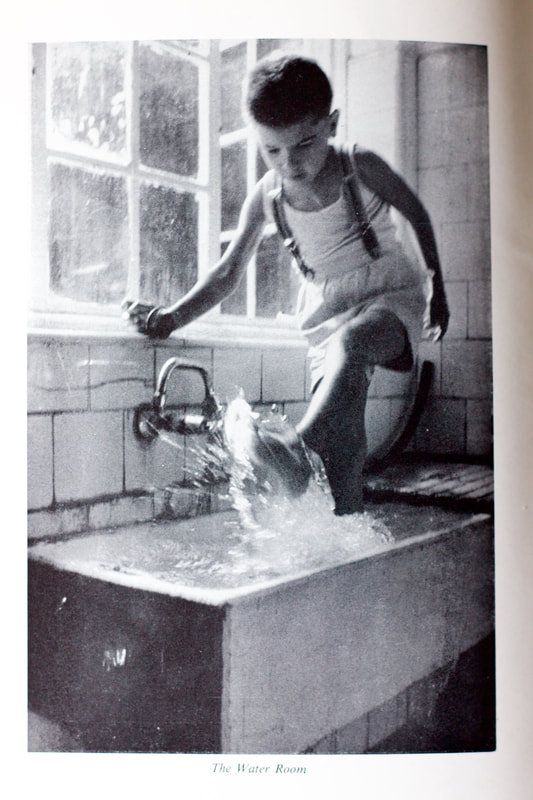

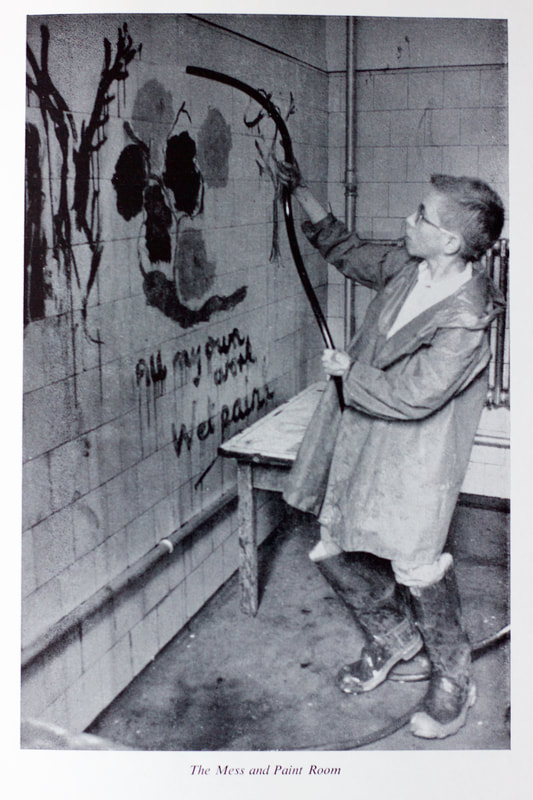

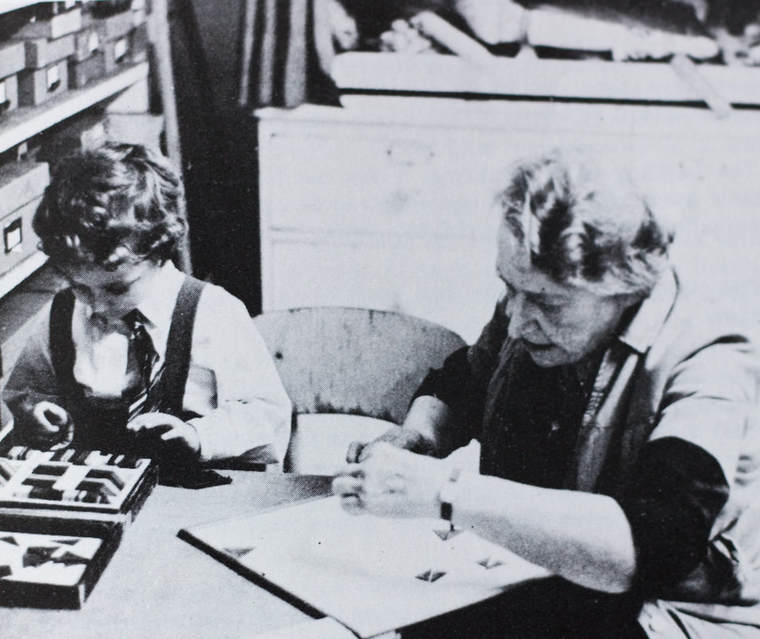

Margaret Lowenfeld (1890-1973) was a pioneer of child psychology and play therapy. She was able to make creative connections of the highest originality. The child-centred philosophy she developed and its process of therapeutic play-making was the culmination of many factors: central to these being her experience of children traumatised by World War One; and also her observation of the colourful patterns in Polish folk costumes. Her work and legacy has influenced my thinking and art practice, both before and after the Grenfell Tower fire that occurred on 14th June 2017. I have always used a model of art making that was rooted in play and non-verbal processes of communication. I was able to use this during Art for Silchester, a seven month residency that has just ended at Silchester Estate. I worked with residents and children who live across the road from the tower and each of whom are coping with the tragedy in different ways. During these sessions, we made large scale drawings and ceramics which were indirectly connected with the therapy of Margaret Lowenfeld, who first started her work in this area of North Kensington in the late 1920s. I also recently met up with Margaret Lowenfeld's great nephew, Oliver Wright, who is one of the therapists working with the NHS in providing support to local residents traumatised by the fire. But this blog is an interview with Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock that was recorded from July-Sept 2018. She is retired from practice, but was trained at The Institute of Child Psychology in the early 1970s and was the leading proponent of Lowenfeld Mosaics as applied to child psychotherapy. In talking about her life and work as a Lowenfeld therapist, I was also able to open up and have a reflective space to think about my own feelings, my inability to voice them over the past year and how I am now moving forward as a person and artist. A war child in Hong Kong and China I was born in Hong Kong, a British colony in 1935. My parents were both teachers. When they graduated from university they started their own school based on my mother’s ideas. She was an intuitive teacher and had this notion that when you teach a child it isn’t just the teaching that counts. It is also about the child. In Hong Kong during the 1920s and 30s that was a rather unusual idea. When the Japanese took over Hong Kong they changed all aspects of our lives including our consciousness. When my brother was born, my parents decided they didn’t want to live under the Japanese and they went to Canton, China. We had nothing and squatted in an empty house. My parents had to have two jobs in order to have enough money to feed us. I was left on my own and wandered around quite a bit. I once stumbled across this march. Being small and very inquisitive I wiggled to the front. There were two Chinese men being executed by the Japanese. The whole crowd watching was Chinese. As soon as one of the prisoners stepped forward the crowd cheered. Then a band of soldiers tried to shoot him but he kept on spinning and it took a long time for him to fall. The crowd just kept on cheering. I was an innocent child and didn’t know anything about politics, but I thought: fate was going to show the people this was a good man. Children see things that they don’t understand and they have to make some sense of it. I didn’t see him fall and I thought he was a good man. That thought came to me as a child and I only found a word for it, patriot, when I came to England. So the words come much later in my understanding. After some time my father returned to Hong Kong to see when it would be safe for the family to return; leaving my mother, my baby brother and myself in Canton. It was during that period that I met a Japanese boy. The meeting was very curious because the Japanese boy was trained to think that Chinese natives were bad. I was walking with my brother in my arms and he threw a stone at me. It hit my elbow and I got really angry. I rushed home, dumped my brother on the bed and went back. I said you hit me and I’m going to hit you back. It was very foolish of me because I was eight and very tiny. He was about ten or eleven. He was so shocked because I could speak Japanese. He then said: if you can speak Japanese, you must be educated and civilised. So he wouldn’t fight me. We became friends and I learnt even more Japanese from him because I didn’t have anyone else to play with. My mother knew nothing about this Japanese boy because she was so busy earning our rice. Just meeting him prevented me from thinking that all Japanese were bad. This later fed into my understanding that all group prejudices were a generalisation of personal experiences. Life is not simple. It’s not reasonable. It is not governed by things like - if this happened here, then that happens there. There is a war, but for the individual child all kinds of experiences are possible. These were war-time relationships and had no consequence afterwards. But even now, I sometimes wonder what happened to that Japanese boy. A scrambled education and life in post-war England We came back to Hong Kong in about 1946 with a wheeled cart and the little luggage we had. My father had found a flat. I continued to look after my brother but not for long. My mother wanted me to go to school, but I had missed three years and so my Chinese wasn’t up to standard. So she decided to put me into a school where the teaching was in English. I didn't know any English. I was 11 and had to spend the first few months writing nothing but lines: I MUST HAND IN MY HOMEWORK. I was always semi-bottom of the class. In my school leaving year, I failed in everything because I couldn’t be bothered to study. It just seemed too difficult. My mother asked me if I would be happy to be a street sweeper or a secretary. It was then that I realised the value of an education that enabled the individual to have a wider choice in adult life. So that year I started to study. When the exam results came out they would be published in newspapers and the top 50 students would get scholarships. I got one. That was such a shock. I later discovered that my mother had been saving money for my education. But my father would always say - don’t overeducate your daughter because she won’t get a husband. You can see there were two very different philosophies in the household. But in the end he was very proud of me. At university I knew I had to study hard. I studied political philosophy. I did psychology, I did logic. All the kinds of things you don’t get at school. Wonderful. I was just enjoying my life. I wanted to become a librarian because I love books. The only post-graduate course on librarianship in the whole of the UK was at University College, London. They had lots of foreign students but they only accepted people with First or Upper Second Class honours degrees. I was very lucky to get in. They said do you have a classical language? I was very cheeky and said I have Chinese. I didn’t tell them that I only studied basic Chinese. They said, they didn’t have a Chinese student and we’ll take you even if you haven’t got any Latin or Greek, nor German or French. This must have been in 1958 and it was a one year intensive course. During the second term I had pneumonia. I was staying in a university hostel and the registrar who was looking after me thankfully had a nursing background. When I went to take the exam, there was no way I could pass it. I passed one paper. I failed the other. They said we really want you to pass, so come back. But I had no money and the course was teaching you how to catalogue Latin manuscripts for working in a university library. It was not for public libraries. I thought this is all too alien and that I couldn’t continue. Domestic life and the discovery of a vocation I then thought I might enjoy teaching but got married and had children. I had to learn how to be a housewife and mother in England. All without any help. What I discovered was that I could talk to another PHD person but I didn’t have any ordinary language. My husband was working in the Midlands as a salesman and he travelled all over the place. We were living in a new estate which had just been built and I didn’t know anybody there. The biggest town was Bromsgrove and that was at least three miles away. We had no telephone. My husband just thought: this is your domestic scene and he decided to have a mistress. I said, this isn’t right, is it? We can’t carry on together when there’s no connection. So I was in a terrible bind and came back down to London. Then he followed with the children. I had to get a job. As I was the one who left, I had to help with the family finances and earn enough so that my husband could have some of my earnings as well. Then I met Jasper. We discovered that maybe we should get together. Jasper and I were married for 46 years and the children lived with us. The children have always thought of him as their dad. During this period I also had personal therapy. The therapist said to me: I can see that you don’t want to be a librarian anymore or a teacher. Do you have any ideas? I said: yes, I want to sit in that chair (pointing at her). I’m going to be a therapist who sees children. First Mosaic made by Therese upon arrival at the ICP, 1969 The Institute of Child Psychology (ICP) I went to Hampstead to visit the Tavistock Clinic. They said you can’t see anybody because they are seeing children and they are in private practice. I said: how do I find out about your training? Well, you’ve got to come to attend our courses. How long will this take? The lady said: it depends on the individual but it could be 4 or 5 years and the student would need to have personal psychoanalysis as part of the training. I just didn’t have the time or money for this. So then I went to visit the Institute of Child Psychology in Notting Hill and they said: Dr Lowenfeld will see you, but she’s with someone else at the moment. They gave me a Mosaic to play with while I was waiting. It was a very clever idea. I knew nothing about what I was doing. It was fun. I made this tree and plane in my Mosaic. In hindsight, I realised this encapsulated my journey and life here in England. The tree was me growing up and the potential to develop in this country through the course. What I didn’t know was that they kept records of all Mosaics and when the Institute closed, I looked through the records and rescued my Mosaic. Margaret Lowenfeld was one of the first child psychiatrists who was interested in finding ways for children to express themselves without only using words. She thought about what happens to a child between age zero and seven. How do children of that age think? She realised that what children perceive is multi-dimensional and cannot be put into words that are in linear time. The child has many ways of seeing the world and they formulate ideas through their sensorial experience. Lowenfeld had this notion that they do it through pictures. So she had this idea of picture thinking in the late 1920s and 30’s and pioneered the use of Mosaics and the World Technique; the latter known more generally as the sand tray used with miniature toys in dry or wet sand. These are play and language tools for the children to express themselves without relying solely on words. Lowenfeld opened the Children's Clinic for the Treatment and Study of Nervous and Difficult Children in North Kensington in 1928. This offered a unique form of therapy for children that did not exist anywhere else in the country. Before the Second World War, the clinic was very well known and mainly supported by private funds. Lowenfeld wasn't charging the local people very much because this was a poor area and she wanted these children to have the use of these facilities. Photographs of Margaret Lowenfeld and children using the World and Mosaic. There was a change of name and The Institute of Child Psychology relocated to 6 Pembridge Villas in Notting Hill Gate. The Institute had facilities that were exclusively given over to the self-generated play activities of children. There was a big basement to the house where the playrooms were located. The children could play ball and use climbing frames. There was a trunk on wheels which the children could hide in. Another trunk had clothes and hats and objects. This was used for dressing up and often lead to dramatic play in innovative ways. There was also a painting room where the children could paint on the walls. You could hose off the paint with water to obliterate the child’s painting should the child not wish for the painting to be kept. There was also a water room where you could have water and toys on the floor and we all had to wear waterproof clothing and wellingtons. The older teenagers might think that playing was too childish and so they could talk in what we called the Quiet Room. Occasionally we would take a Mosaic in for them to use. The Institute always had a file for each child’s therapy work that included a recorded copy of all their Worlds, Mosaics, drawings and paintings. At any given time you might have 6 therapists with their children in the playrooms. We worked together as a team, often helping out by observing other children when the therapist might have missed out on some aspect of their child’s action. It was also a very demanding training. I could write about 12 pages of notes that documented what my child did in any given session. We would never impose a point of view or interpretation of their play. The aim of all this was to allow the child to express their point of view and feelings through play. I started my post graduate course in 1969 and this lasted three years. We only had two new students per year. We had daily supervision, but on Tuesdays and Fridays we had two hours of group supervision to discuss what we called Corporate Cases; these were the children who were not solely the patient of a particular therapist. In the student’s last year, they would be supervised by Lowenfeld. I liked doing the Mosaic and the World with the children. It could take two sessions to do this because sometimes children take forty minutes to do a Mosaic. I prefer to use the Mosaic because they have a progression or a regression and they tend to be linear. I don’t interpret the mosaics. I talk to the children through it and then sometimes they will tell me what it means. The Lowenfeld therapist always had to be lower than the child. I would sit in a chair that is the same size as the child. I’m lucky because I am fairly small anyway. Lowenfeld was not psychoanalytical. She said her ideas were only just one philosophy and so we were taught about Freud, Klein and Jung. She said you will need to understand what other professionals might tell you about the child under consideration. The Institute had a child psychiatrist, an educational psychologist, a social worker and a West Indian social worker, as the area the ICP was in had a lot of West Indians. I think I had an excellent training and it never troubled me that the psychoanalysts thought I was not trained. Lowenfeld had set up a proper postgraduate institution and awarded postgraduate diplomas. They had an academic board who oversaw standards. That’s why I got a student grant because it was properly recognised by the national Education Department. Case studies and sexual abuse I remember this nine or ten year old girl who came to the Institute and just stood rigidly. She believed that her back was made up of one bone and that she couldn’t bend her body. She only spoke in whispers, not wanting to expend her energy reserves. She was worried that she would die and had stopped eating. I said to her: do you know what our back is made up of? She said there’s a bone there. I said your quite right but there’s not just one bone but many bones. I’ll show you. We had these models. I got her the skeleton and I went slowly down the spine guiding her hand so she could feel the knobs. The first treatment objective was to get her to learn about moving freely. We often did body work because, for instance, many girls didn’t understand about menstruation. There was also a fifteen year old Indian girl who was very unhappy and wasn’t eating. She told me she was going to have an arranged marriage but wanted to go to university. The parents felt that any further education would be unnecessary since their aim was for their daughter to get married immediately after leaving school. To enable her to get into university, I said: you have to go to the library rather than home to do your school work. Sometimes therapy is being pragmatic for people to get out of these difficult situations. You’ve got to offer them a solution that will relieve them from that. Only then can it be analysed and if the child wants it to be. What happens if the daughter is expected to sleep with the parents? I said okay. Which side of the bed are you sleeping? I’m sleeping on the right hand side. Who else is in the bed? Mummy is on the other side. So I asked who is in the middle. That’s daddy. I asked her how she liked the arrangement. This is a thirteen year old girl and was a case of sexual abuse. There are girls who I can discover their issues through their World Play or like that girl who did a Mosaic. She kept on shoving Mosaic pieces in between other pieces. I said sometimes that happens to older people as well. She nodded. I said: it also happens to girls. What you need to do, to stop this, is to tell an adult. There’s a law that allows me to talk to you about this. I was getting somewhere with one child who was telling me the parents were abusing her. The parents then stopped her coming to see me, saying Mrs Woodcock’s English is so poor that my child can’t understand her. You can’t argue with that. What I said to the girl was: I’m sorry this is your last session because your parents are not happy about you coming. I said: you know what the problem is. You are fifteen and by the time you are sixteen, you can leave home. That was all I could say. Perhaps there are limits to the therapeutic process. Lowenfeld never talked about sexual abuse at all. You would think she never knew about it. But you see nobody was talking about it at the time. The biggest change I saw over these years was actually having abuse recognised and also the legal aspect of myself and social workers having to report it. I thought that helped me to talk to the children. By law, I had to report this and some other professionals were then able to help the child. In Summary I am extremely grateful to have attended the course at the Institute of Child Psychology. It enabled me to help children by using the World Technique and the Lowenfeld Mosaics. When I graduated in 1972, I worked for the NHS and child guidance clinics in Newham, Haringey and Barnet. Both Haringey and Newham were multicultural and deprived areas. I didn’t actually want to work anywhere else. That was a personal choice. I wanted to work with a variety of children including the poorest. I saw my last case in January 1995 having worked as a Lowenfeld therapist for over 20 years. A selection of my work will be housed at the Wellcome Library as part of the Margaret Lowenfeld archive. Expressing the shape and colour of personality: Using Lowenfeld Mosaics in Psychotherapy and Cross-Cultural Research By Therese Mei-Yau Woodcock, Sussex Academic Press, 2006. Photographs and text kindly reproduced: © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library. Postscript Let us end with Margaret Lowenfeld's account of the first day the Clinic opened on Telford Street in 1928. This was in rooms hired from the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre (aka birth control clinic) where Margaret's sister, Helena Wright, worked as the Chief Medical Officer: The two rooms that allowed for the Clinic's work consisted of one opening direct on to the street, which we used as treatment room for the children, and a second room opening out of it. Here records could be made and kept, parents interviewed, biomedical investigations carried out and discussions conveniently held between myself and my colleague. Money was short so the playroom furniture began as one table and three chairs, one of them a fireside chair placed between the diminutive gas fire grate. The play material was kept in the second room and carefully selected for each child who came - it was too precious to be indiscriminately displayed. Later a second table was added for the children to paint on, the first round table remaining in the centre of the room. A scene in which this table figured later won us our crucial friend. The first child who came was the "bad boy" of the neighbourhood, abominated by the shopkeepers. He came by himself and I do not remember seeing his mother. He was defiant and silent but remembering the Polish children, I left a French painting book - these were lovely (good ones being practically unobtainable in England) on the table with water and painting brushes. He seated himself with his back to the centre of the room and studied them. Half an hour later I stood silently in the communicating door watching him. His concentration was intense, he breathed excitedly and - schools being different in those days - I found later this was the first time he had the magic of colour in his hands. Every day the Clinic was open he came, and slowly began to talk. By that time I knew his attendance at school was erratic and all efforts to improve this had been defeated by his silence under questioning. We made a pact together: more regular attendance at school on the days and times the Clinic was not open, and fresh paints and painting books when he came. It was from the school we heard later that a different boy had slowly emerged - complaints against him ceased. One day he brought a young friend with him and we knew we were winning our way in the neighbourhood. Constantine Gras making a mosaic, with from left to right: red beacon, tower from black to green to no colour; myself draped in those colours; and a key, a set of arrows pointing to me, the tower and Thérèsa as witness to the mosaic. "I felt I needed something in addition to the tower and me. I don't know what it is. Maybe it's a signpost trying to direct me or others, but everything is shifting apart again over time. Then I step back and look beyond the tower and me. I want to get a sense of the overall space and how these objects function within that space. Can I possibly create something that is aesthetically or emotionally satisfying? I am trying to make a work of art. I'm not sure if that is right." "Yes. You are an artist. You cannot escape that." "I was hoping that I might, but I don't think so." "You won't be able to escape yourself, will you!" "No. No." At Play In The Ruins: A Lost Generation

oil pastels, 33x24" 19 Dec 2016 Artist's comments on the reverse of the drawing: Starting off with abstraction, but thoughts turned to Lowenfeld sand play (Sand Face in the picture) and childhood. The news on the following day. The battle and now the desperate evacuation of Aleppo in Syria. One of the defining media images of the year, Osman Daqneesh pulled from the bombed building. His haunting stillness in the midst of horror.

7 Comments

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed