|

Over the past decade, I have had the unique experience of working with residents and the diverse communities on three social housing estates in North Kensington: Silchester Estate, Lancaster West Estate where Grenfell Tower is located, and, in the past few years, Wornington Green Estate. It has been challenging but has resulted in a rewarding body of work across multi-media, with film making always at the core. The bitter and sweet fruits of this labour come into sharp and public focus in the coming week.

On Wednesday 8th September, Grenfell: The Untold Story will air on Channel 4 at 10pm.

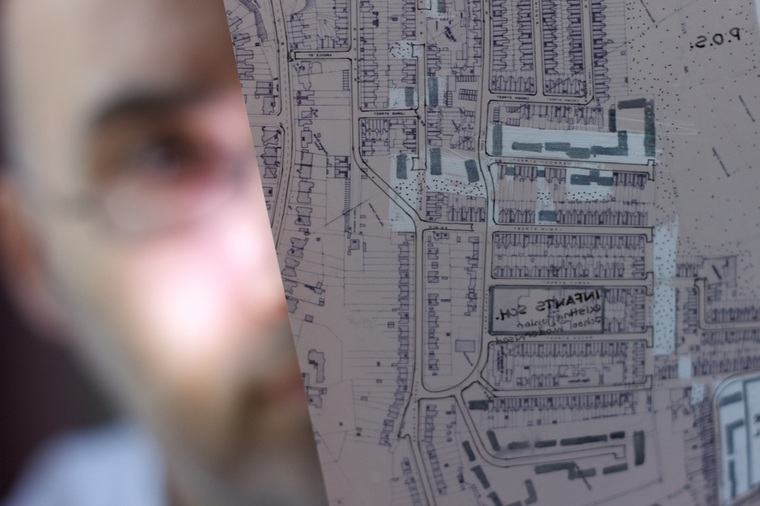

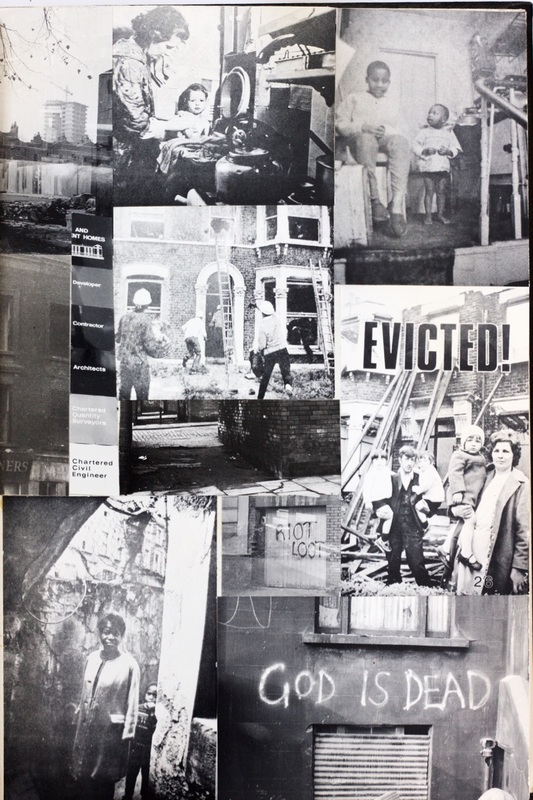

Before the tragic fire, I documented the struggles of Grenfell residents who raised issues and concerns about the work being carried out. Using footage never previously seen, this film forms a prequel to the disaster casting the tragic story of Grenfell in a new light. I've been holding onto film footage and photographs for over 4 years. It was handed over to the Metropolitan Police a month after the fire and over the years was made available to various members of the bereaved and survivors. Now that the police have cleared my use of the footage, it's the right time for it to be shared in a powerful documentary made by director and producer, James Newton and Daisy Ayliffe.. What were the circumstances that lead me into becoming an artist "in residence" at Grenfell Tower? I am deeply interested in the social aspect of art and the political issues this entails. In 2010, I made a commitment to working in and around the two estates of the Notting Dale ward in North Kensington - Silchester and Lancaster West. This patch of land has a fascinating and troubled history from slum housing to race riots. The estates that were built in the 60s and 70s were undergoing controversial redevelopment and this allowed me an opportunity to connect and explore. A nursery being closed down. A row of social housing on Shalfleet Drive was about to be demolished. Why and how were these taking place? It meant creating art that really connected with local residents. I may have been naive in approach, but not feeling. And it was based on this experience as a community-based artist and being employed by the V&A Museum as their first (and only) community artist in residence, sited in a council house about to be demolished for the More West development, that I caught the attention of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO). In 2015 they contracted me to make a short promotional film and large scale art work for Grenfell Tower as it was being renovated. I worked on this project for approximately a year. Early in my engagement, I made a decision to deviate from my contract and make a feature length documentary that ended up being called The Forgotten Estate. This was based on interviews with six residents who lived on the estate, in addition to the original architect and estate inspector. It was an attempt to use film to facilitate mediation and shared understanding between the TMO and residents who were in deep dispute over the impacts of the building works. The residents asked me to film meetings and a Fun Day. The TMO told me I would not be paid for this. The TMO never adequately engaged with the film I made seeing it as the same tired old voices that offered nothing new and marketable for them. I subsequently delivered a short 10 minute film to the TMO that featured no residents but portraits of the Boxing Club and Nursery that had moved back into new premises in the tower. I have only screened The Forgotten Estate on several occasions and have now withdrawn it from public viewing. The art work that I was commissioned to make also had a frustrating outcome. The TMO never hung up the completed work in the Tower and so it was not destroyed in the fire. It now resides in the offices of Grenfell United and a copy in the Houses of Parliament. Grenfell: The Untold Story will powerfully illustrate through the voices of residents, how a £10 million refurbishment that resulted in flammable cladding and insulation being installed, failed to meaningful engage with the desperate concerns of residents and the tragic consequences that resulted. The causes of the Grenfell fire are complex and multi-factorial. But this lack of engagement and duty of care to the residents was a significant failure. I hope that this film will have an emotional and soul searching impact on the wider public, politicians, local authority, architects and the building industry. Also on Wednesday 8th September a short film called A Spell For Wornington Green, was released by Channel 4 on the Random Acts platform. The film was shot over 2020-2021 during the Covid lockdown on Wornington Green Estate in North Kensington and follows the life cycle of two baby pigeons and the subsequent coming together of the community in direct action to prevent the felling of 37 trees as a consequence of urban regeneration by Catalyst Housing. Wornington Green Estate is half-way through a 20 year regeneration into Portobello Square. Nick Burton, who survived the Grenfell fire but sadly lost his wife, witnessed the felling of these trees on 1st March 2021 and commented: “My wife is dead because of Grenfell and they still won’t listen to the community.” Whereas at Grenfell, where I very much remained behind the camera or sketch book, I have since taken more direct action and set up the campaign group Wornington Trees. We are challenging the mass felling of mature trees in one of the most polluted parts of London. We have a second petition presented to the Council that was signed by nearly 2000 residents. It calls on RBKC to compensate us by planting an Urban Forest in North Kensington and to stop Catalyst Housing from cutting down any more trees until they have consulted. The regeneration of Wornington Green into Portobello Square involves knocking down and rebuilding 500 flats to rehouse its original community, plus the building of another 500 more at market rent or sale, where a one bedroom flat costs £700,000. The lack of real consultation and the resulting loss of green public space and the felling of 100's of trees during a climate emergency is the most deplorable part of what was once deemed a "flagship" regeneration by the Mayor of London.

Filming by Ilaria Di Fiore and music by Taozen.

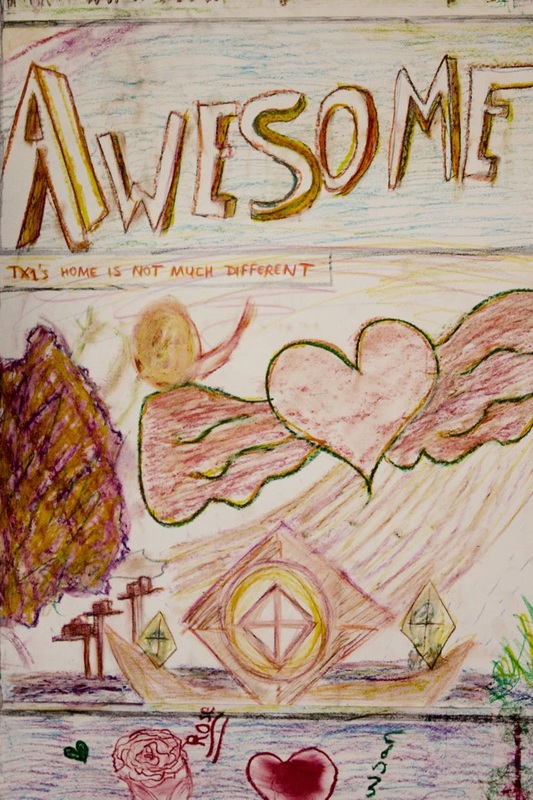

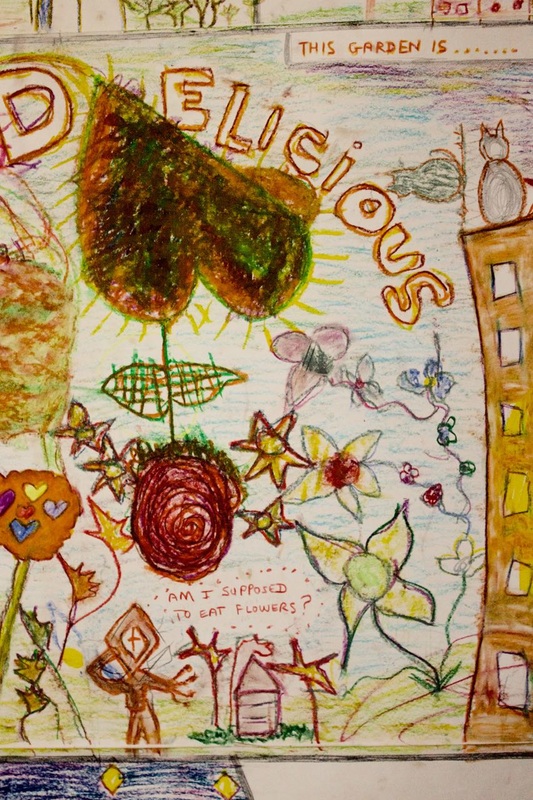

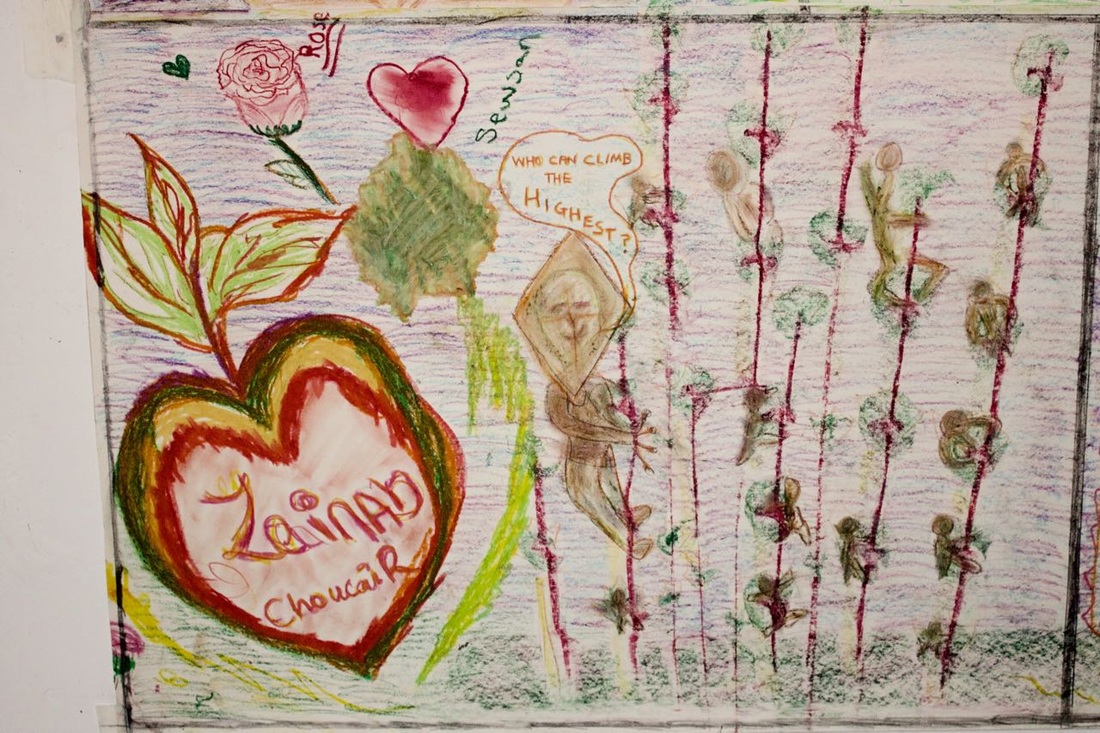

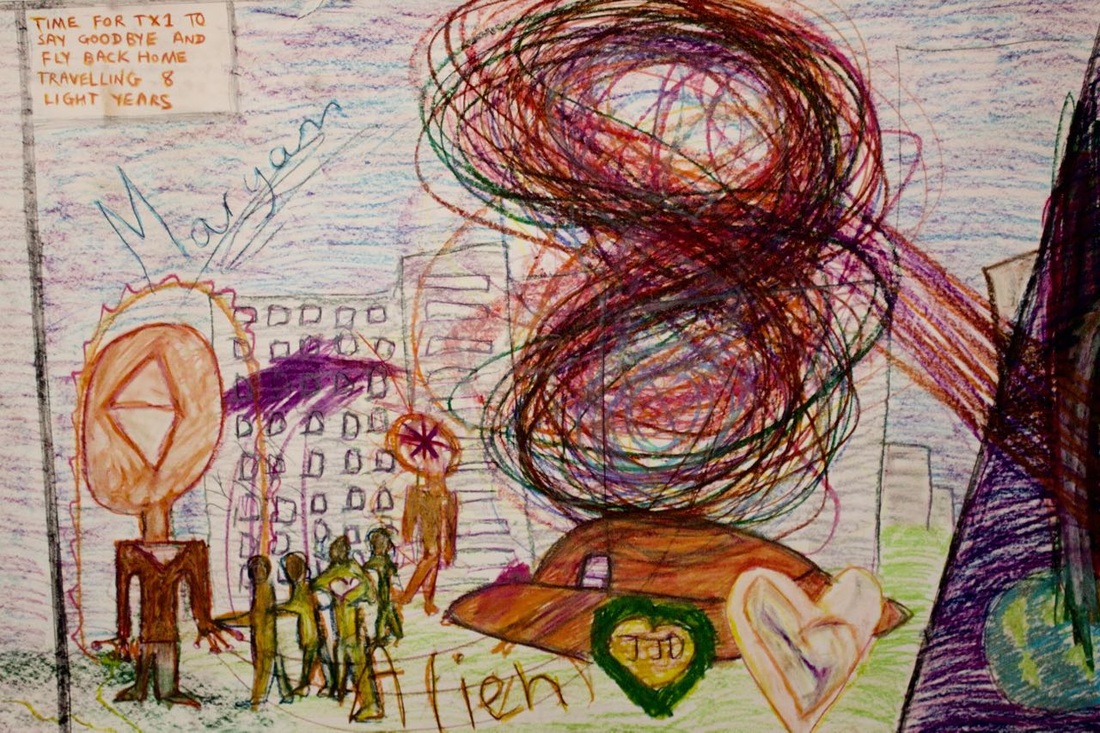

This summer at the pop-up Portobello Pavilion in Powis Square, I displayed several large scale drawings from a series called Wornington Green in Black and White. They tell the narrative story of Wornington Green Estate.

Drawing 1: The Squalor of Wheatstone on Screen

Charcoal 2019 This is based on a newspaper article from 1975 that described how a local resident, Mrs Leq-Roy, borrowed a video camera and made a 20 minute documentary about the infestation of mice, dilapidated ceilings, rotten 'death-trap' flooring and overspill urine running down the walls of the houses on Wheatstone Road. Residents were calling for their slum houses to be pulled down for redevelopment.

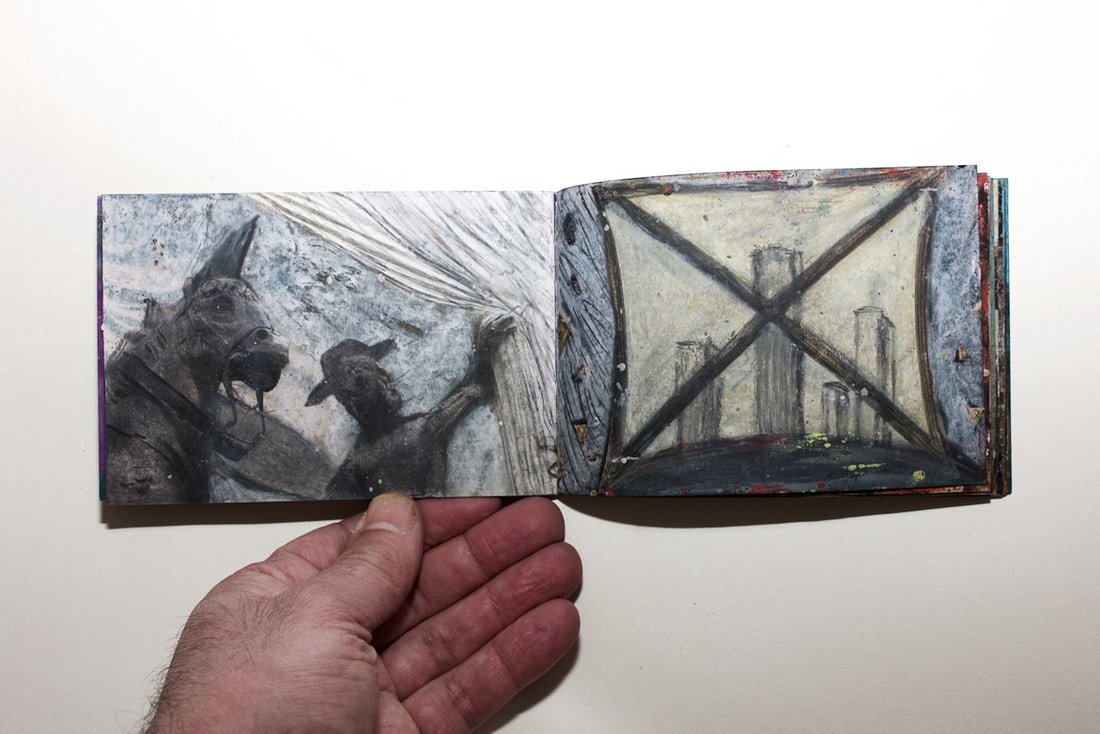

Drawing 2: The Whole Scheme represents a 21st Century Slum

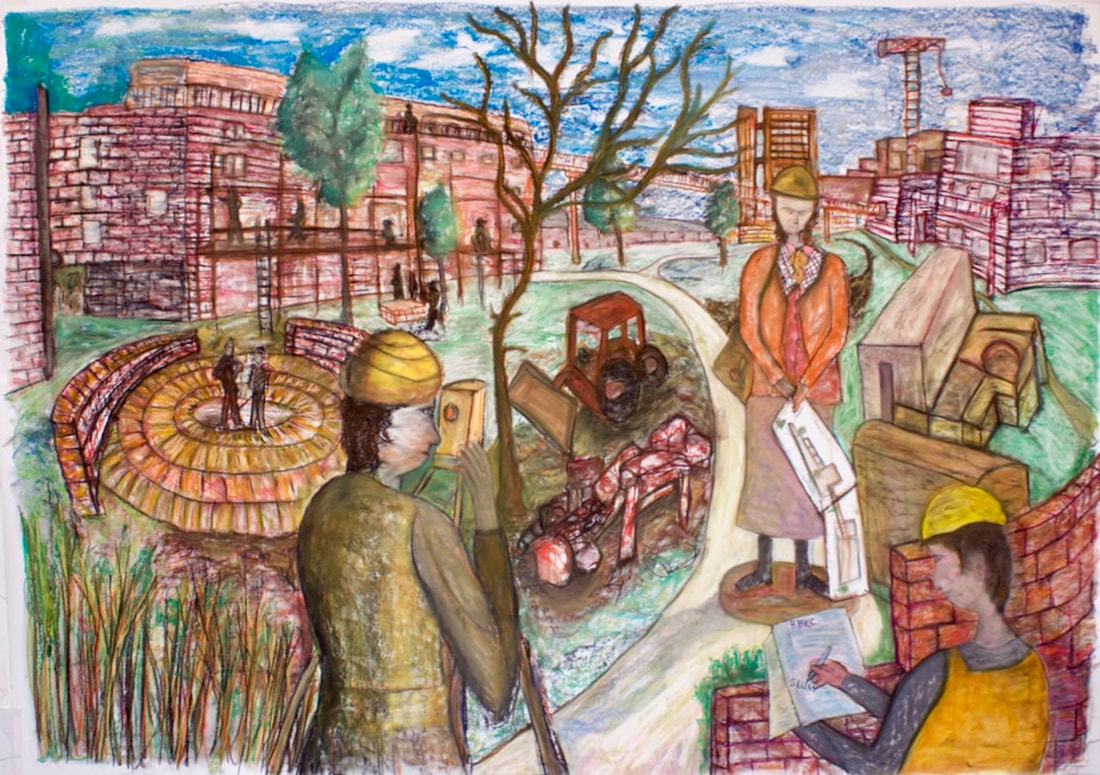

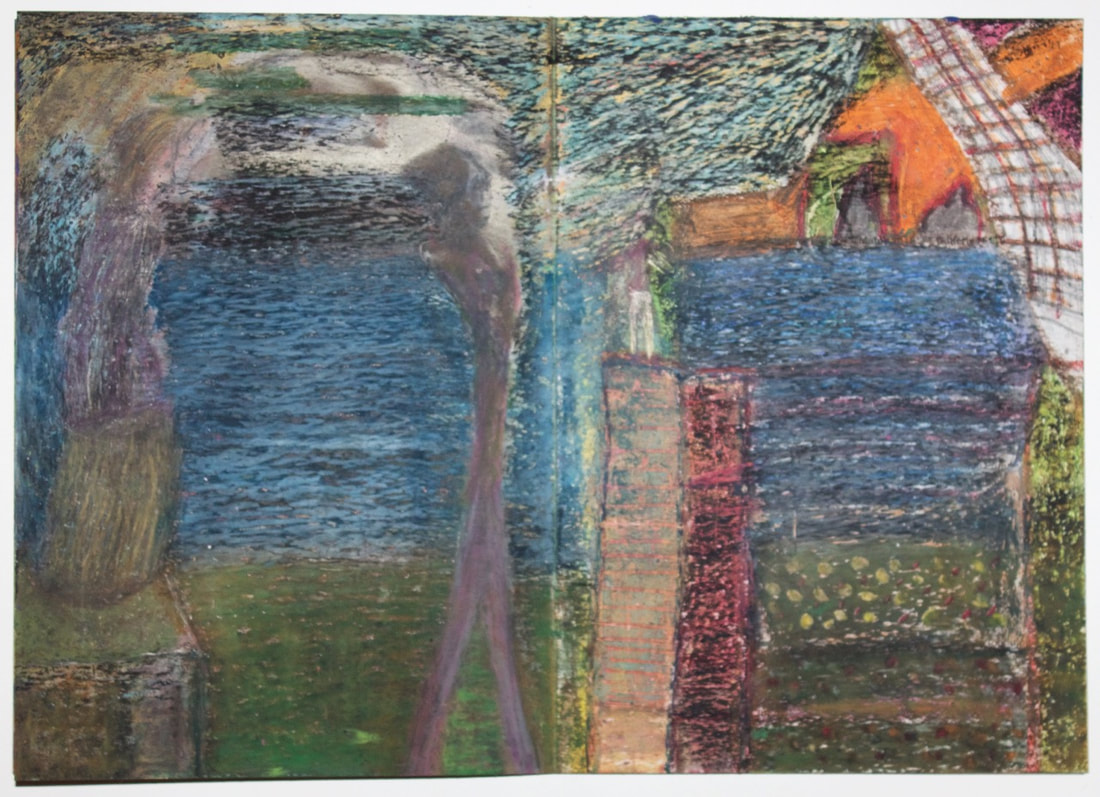

Pastels 2019 This illustrates the lead architect for Wornington Green Estate, Jane Durham, as she oversees the building of the Murchison Road Development that became Wornington Estate. Also present are representatives from the Council's Housing Department. One of whom, in archive records from 1975, stated: "Having had the unique opportunity of being able to view a finished block, it should be obvious that it is an architectural disaster and to repeat this form all over North Ken will be a Planning Disaster! The whole scheme represents a 21st century slum."

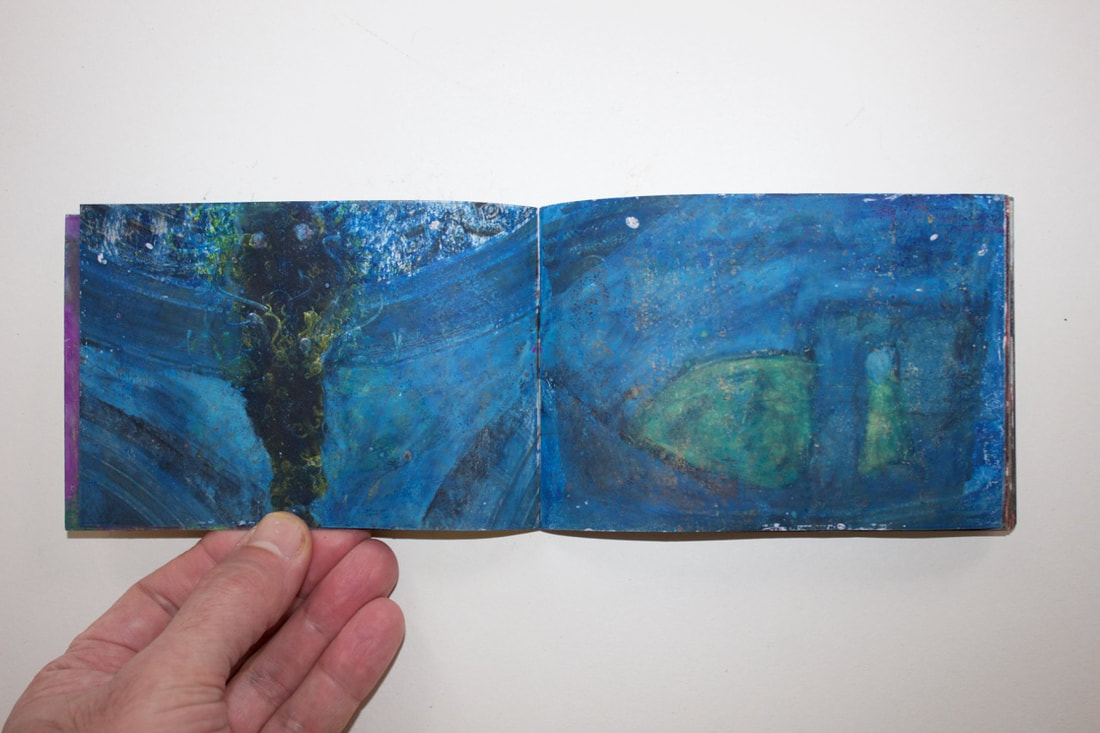

Drawing 3: Building a tree house at Venture Centre

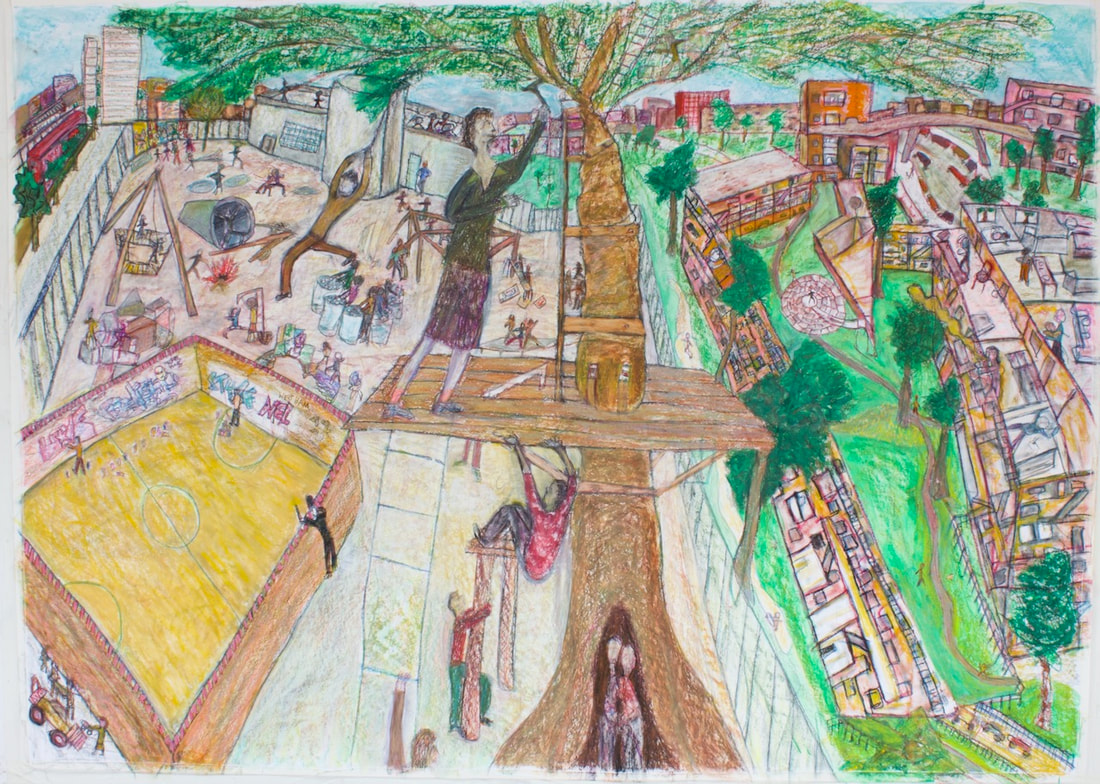

Pastels, 2021 This drawing takes its inspiration from Wornington Word, a heritage project, that documented the voices of residents on the Wornington Green estate. In particular, an audio recording made by brother and sister, Latifa and Rachid Kammiri, who grew up on the estate and played at the nearby Venture Centre (the oldest standing adventure playground in the UK). "It was beautiful living here, it was absolutely the best thing ever, I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else because you were always safe. And we had the Venture playground right next to us which was totally different. Filthy yes because it was just all – it wasn’t even mud, was it, it was just like black dust everywhere. Our parents never used to like us to go there for that reason, you know, because you’d go there clean and come back like mechanics. But it was great. I think what I liked about it most when you went in there, it wasn’t health and safety, you just did what you wanted to do. You had to build your own activities, your own swings, your own slides, you know, from scratch. We literally built the Venture playground together." Footnote: the historic Venture Centre is scheduled for demolition during Phase 3 regeneration of Wornington Green and will be relocated in new premises in Portobello Square. Drawing 4: The great storm of 1987 Charcoal, 2021 This is based on another archive record and a recent telephone conversation I had with Margaret Cairns-Irven. She moved into Watts House on the estate in the early 1980s and described having central heating for the first time - "It was like it hugged us." At this time, the trees on the estate were in full bloom and while a keen gardener and nature lover, Margaret recollected that there were just too many in close proximity and the roots of one had grown into her garden making it difficult to plant anything. The drawing also includes a recollection she made about the Great Storm of 1987. During the night, corrugated sheeting had been ripped off the roof of the Venture Centre and flew over Watts House and she observed the frightening scene of a tree being blown down the middle of Wornington Road at 40mph. But humorously commented - how it was well driven and managed to avoid all parked cars!

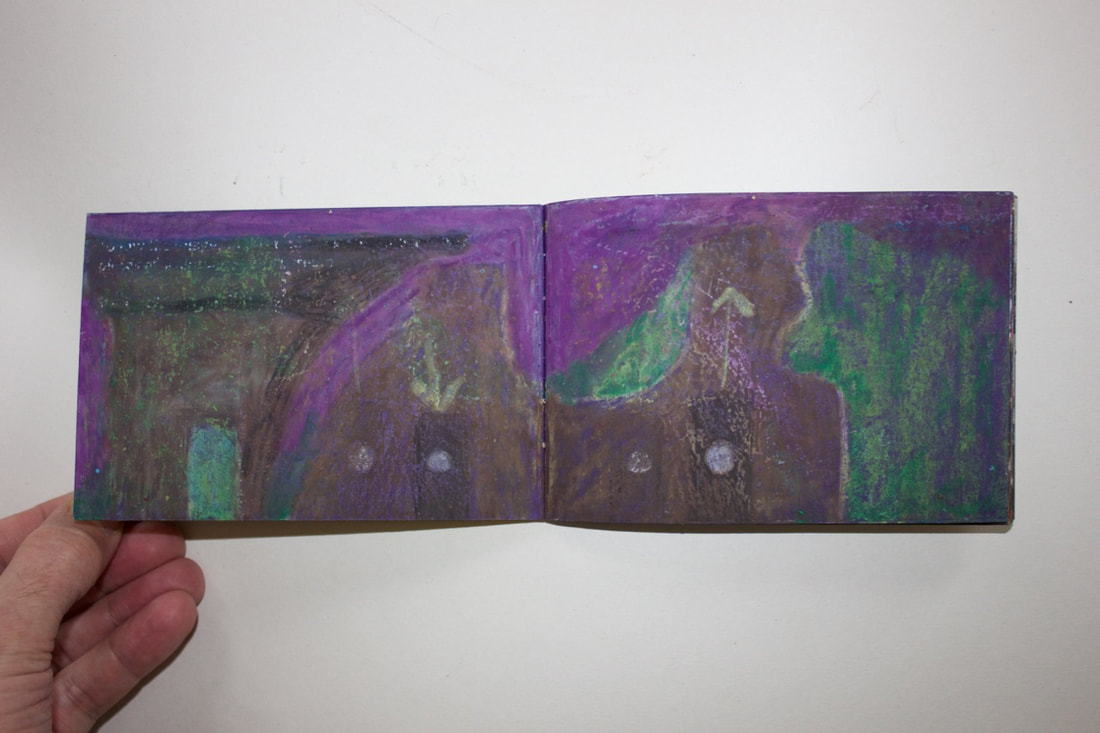

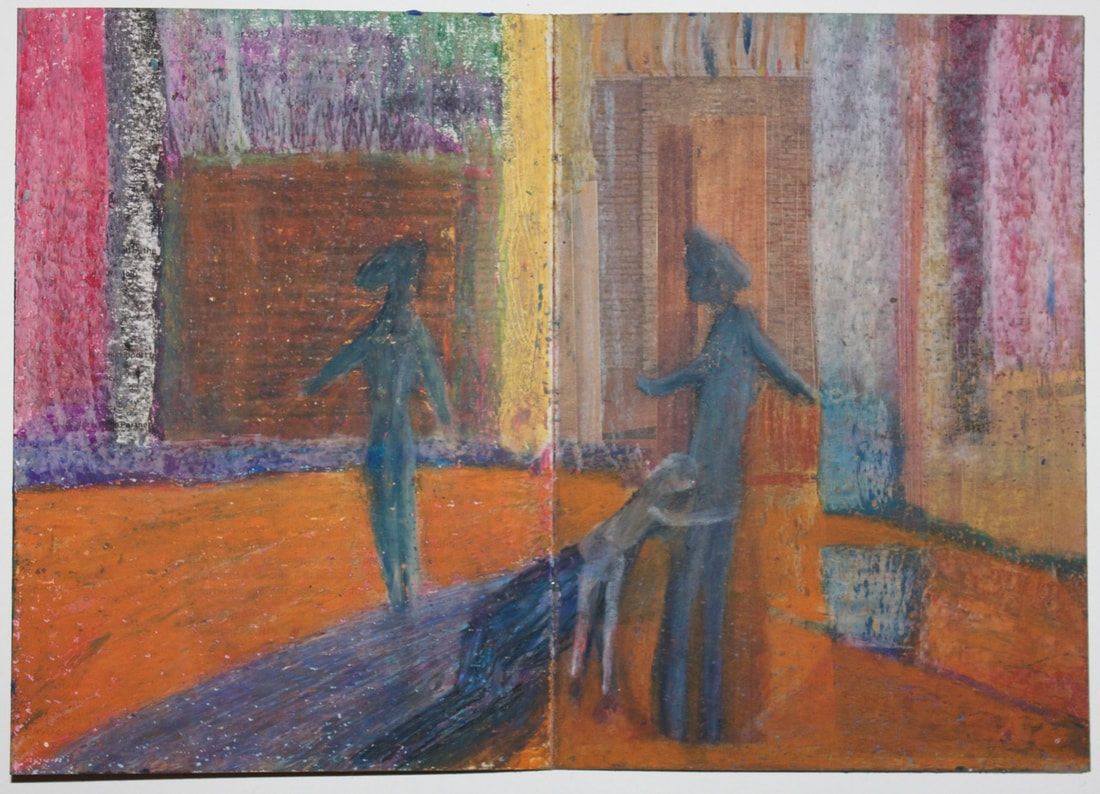

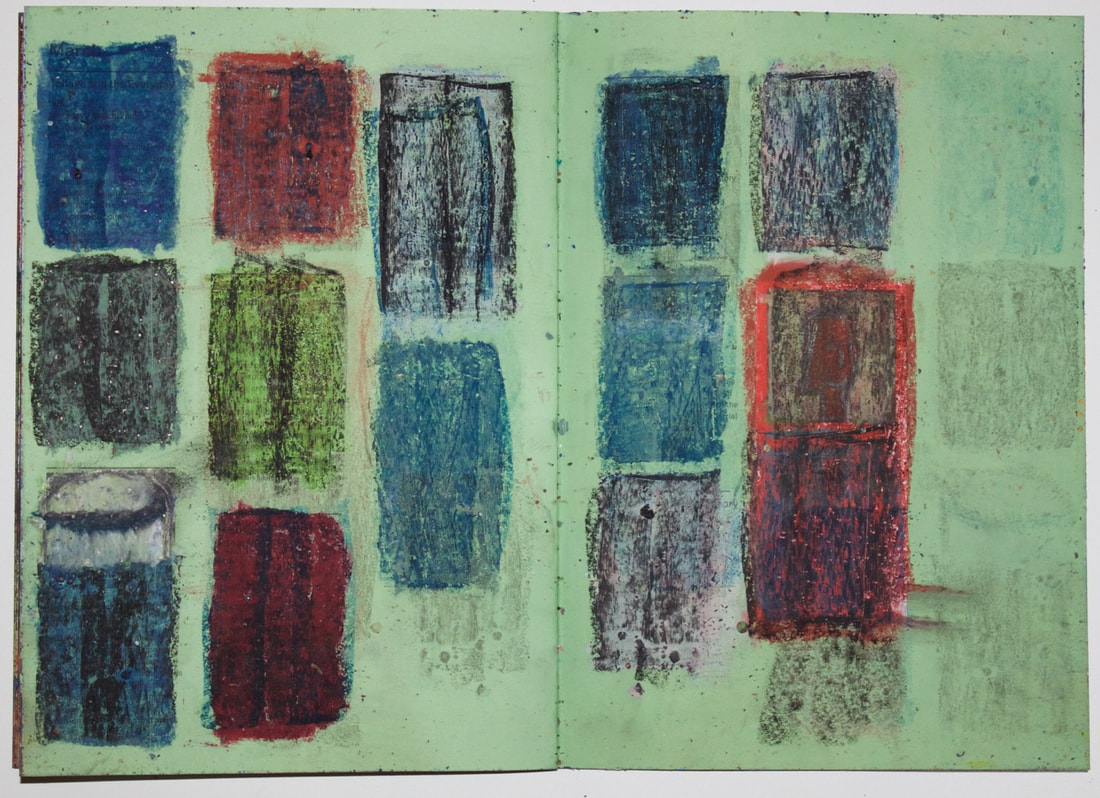

Drawing 5: Resident lead regeneration 1990 and Kensington Housing Trust / Catalyst led regeneration in 2010

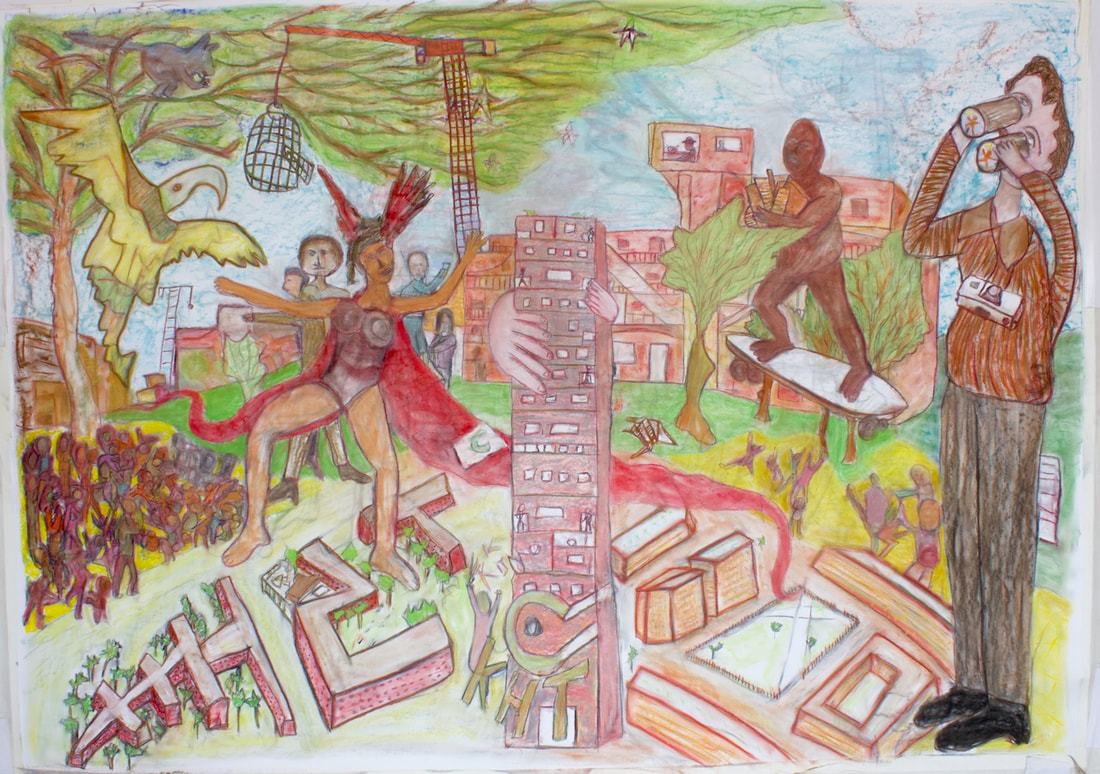

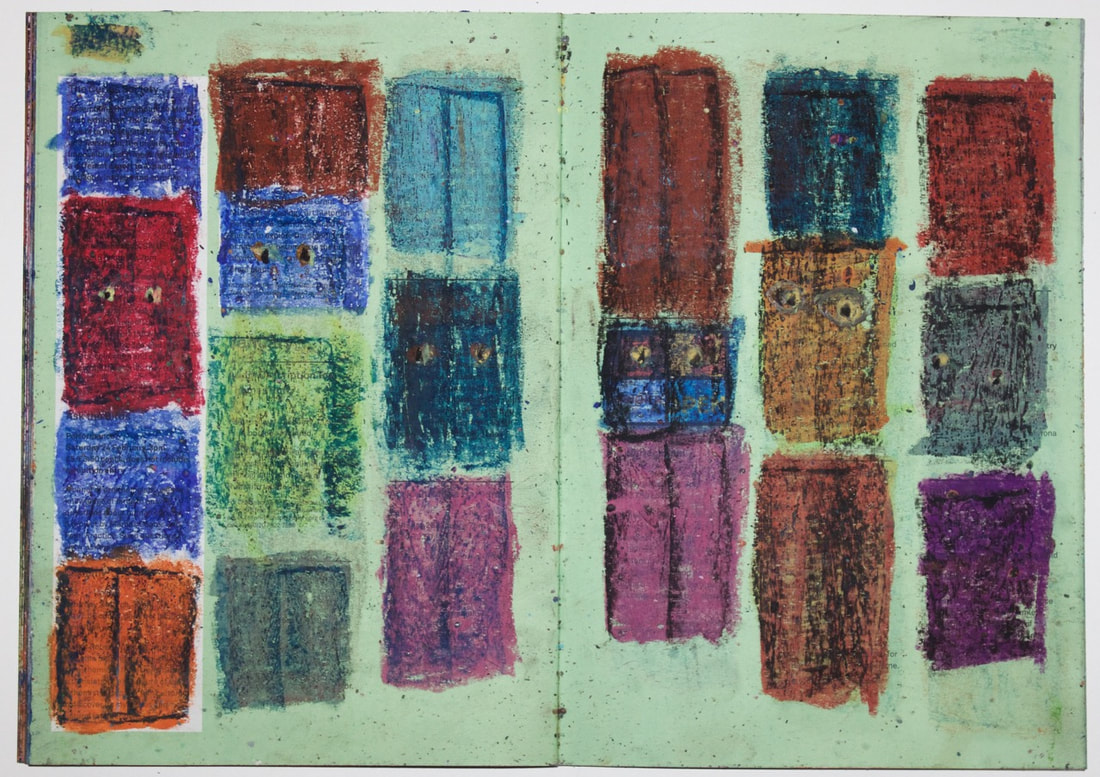

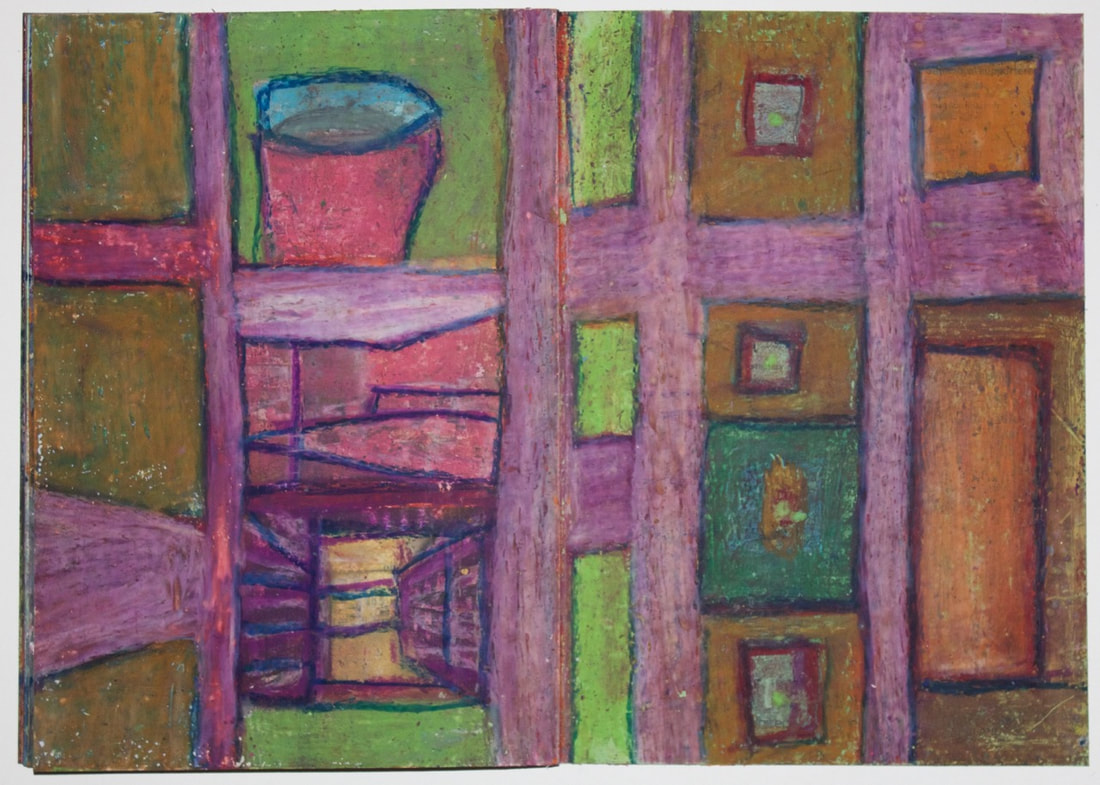

Pastels, 2021 This drawing fuses together past and present regenerations on the Wornington Green estate. In 1990, the residents worked with Kensington Housing Trust to upgrade and install security entrances across the estate. In the archive, a resident newsletter had the optimistic and comedic image of King Kong proudly clutching the new security entrances. In my drawing Kong is bursting through the trees with joy. On the bottom of the picture plane, you can see the original estate with its interconnected blocks and walkways (left channel) alongside the 2010 Masterplan for Portobello Square (right channel). The contemporary architects plan to return the traditional street pattern made absolutely no attempt to build around and incorporate trees into the design. There are several other sweet notes and off-beat flavours in the image. These include the dancing and frolics of Notting Hill Carnival revellers. And the bird-watching of Keith Stirling. He is a life long member of the estate, who had campaigned for decades against the lack of maintenance and proactive management. Keith would resign from the Residents Steering Committee in 2020 in protest of Catalyst's plans to fell 42 mature trees and this inspired me to join him in taking our first petition to the Town Hall.

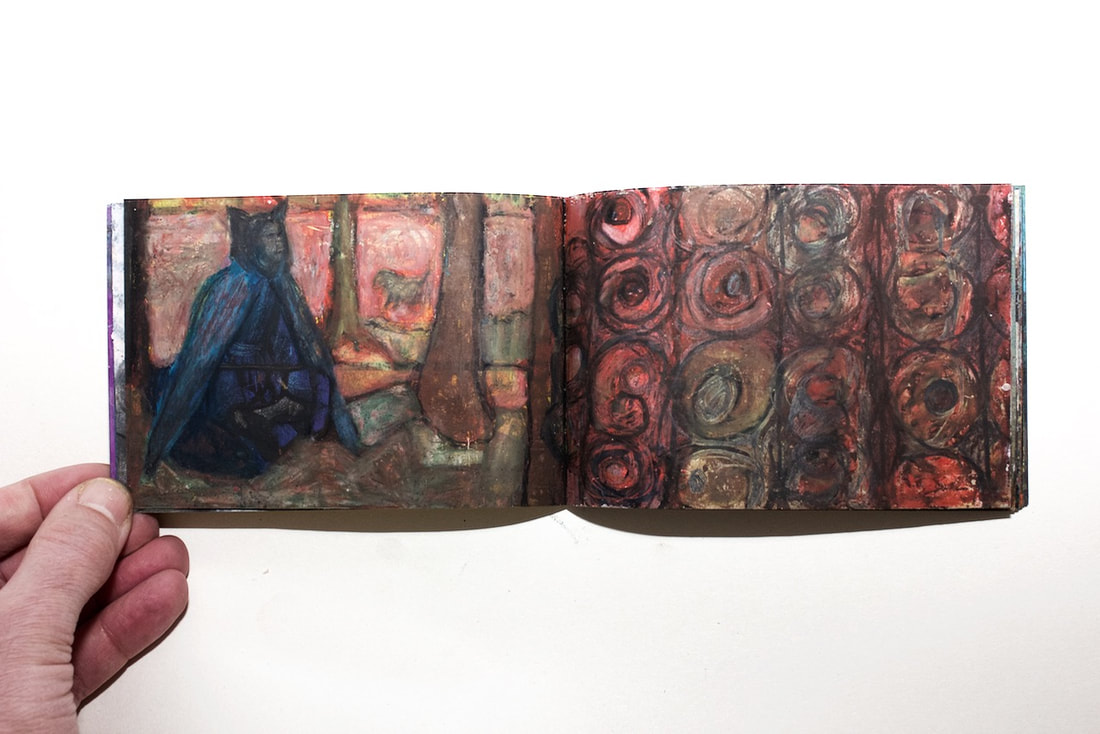

Drawing no 6 - March 1st, 2021.

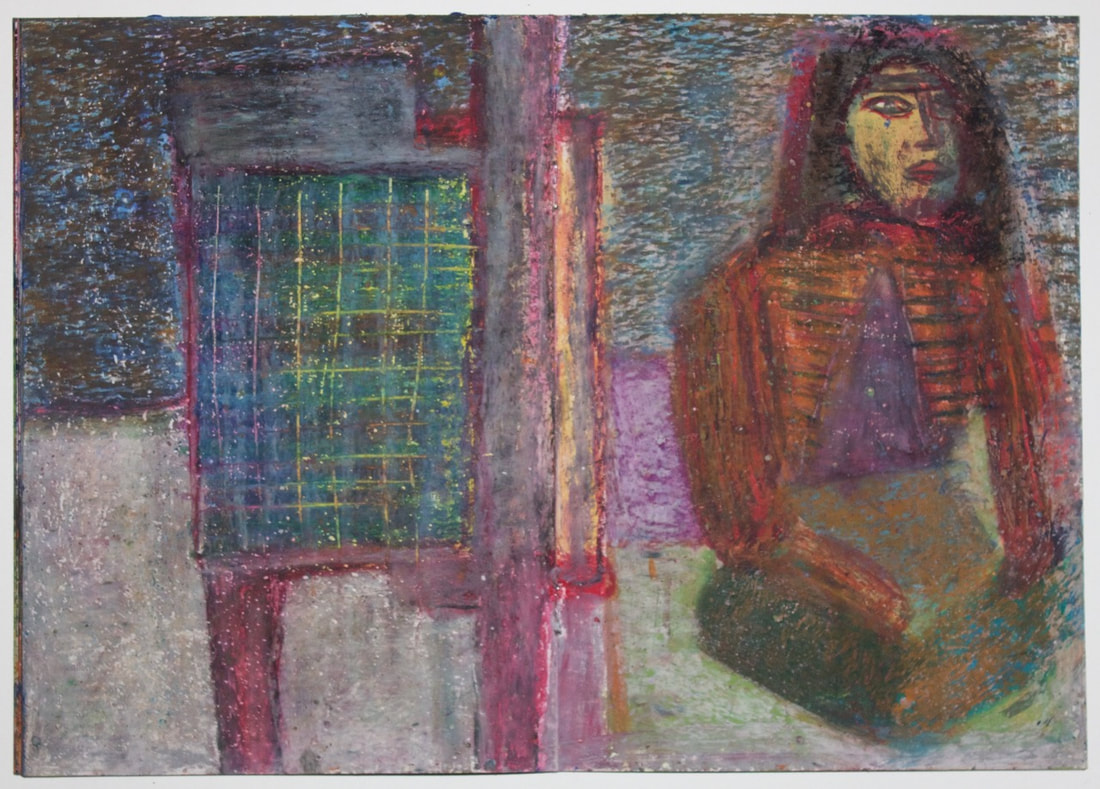

Pastels, 2021 This drawing illustrates the coming together of the community to protest the felling of 33 trees on Wornington Green estate in March 2021. Two women from our community were arrested. Film of this features in A Spell For Wornington Green. I am planning a gallery exhibition of all 6 drawings.

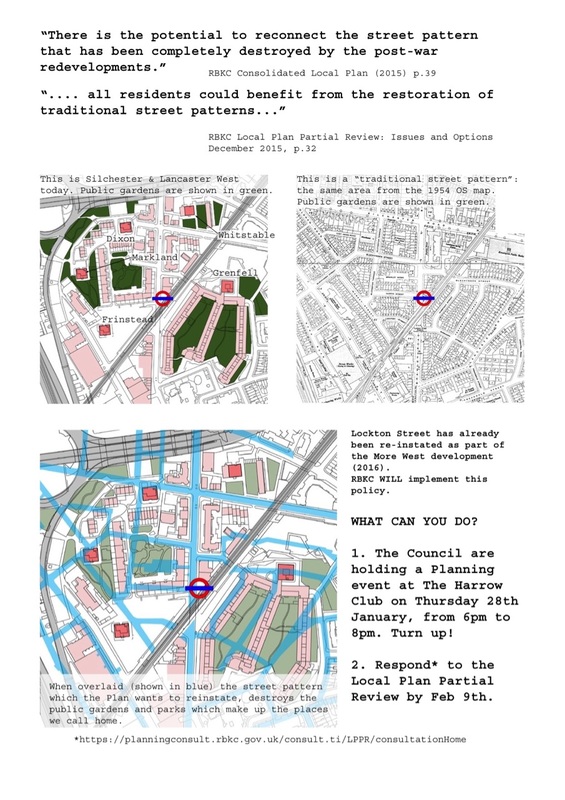

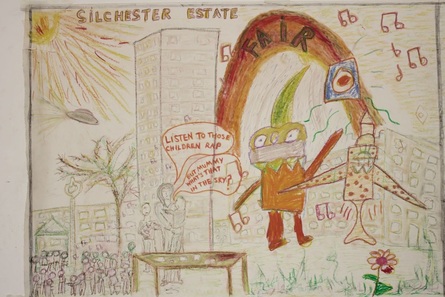

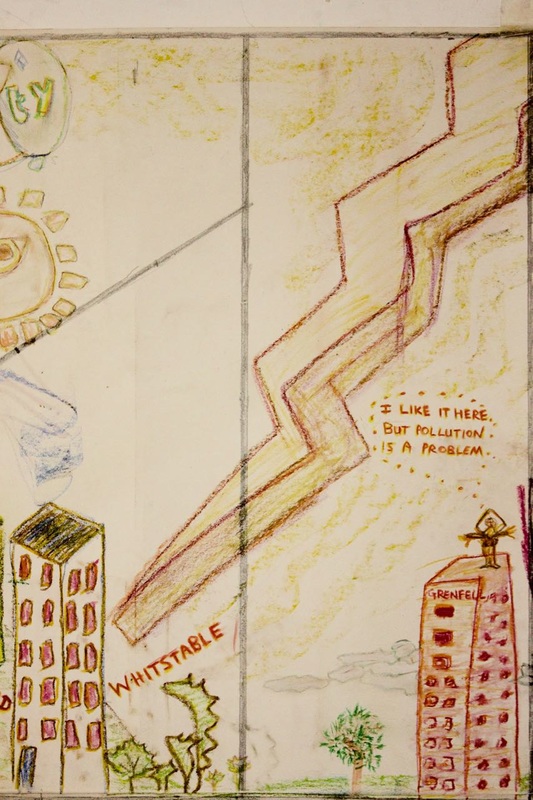

On Saturday 11th September, from 11.30-2pm in Waynflete Square on the Silchester Estate, the Residents Association are holding a public meeting with the Council to share ideas about the future of the estate and how to spend the Grenfell Housing Legacy fund. At the same time in Waynflete Square, we are holding a launch event for the Art For Silchester book that was postponed by the Covid pandemic. This was an arts project I ran from 2018-20 for residents of the estate. Please drop by and see our amazing book and art work. Silchester Estate was earmarked for complete regeneration with the loss of its lovely green spaces. It was only the Grenfell fire that stopped RBKC council from carrying this out. Please visit the lovely square with its beautiful trees.

0 Comments

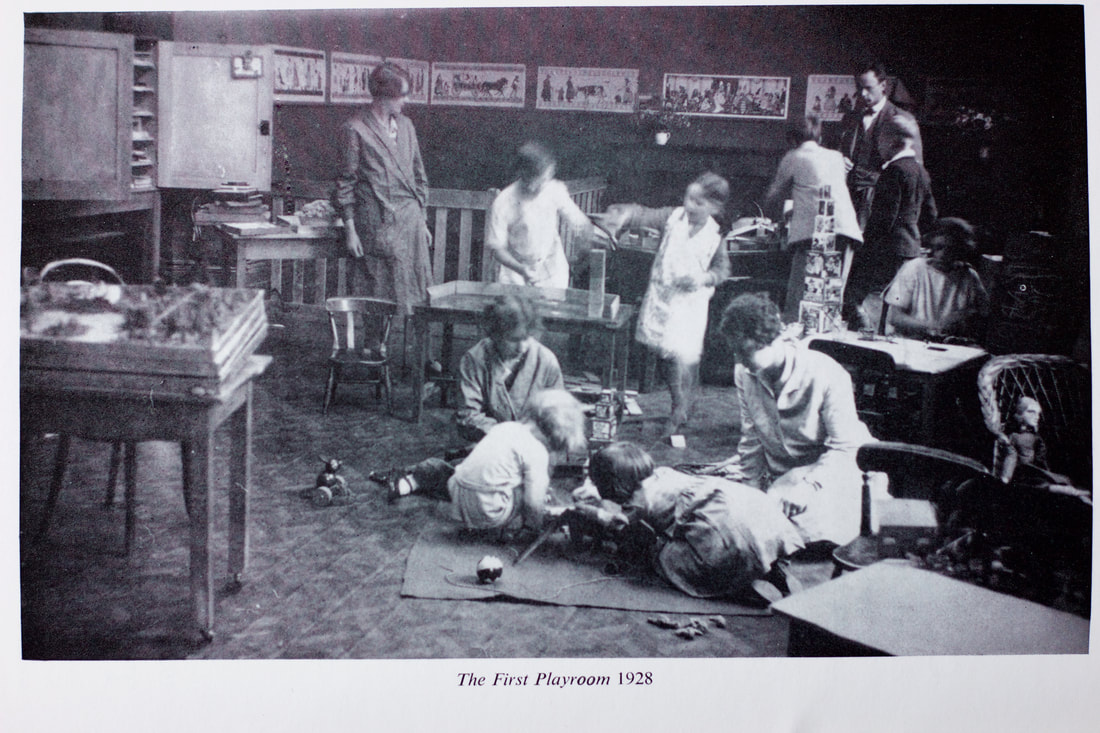

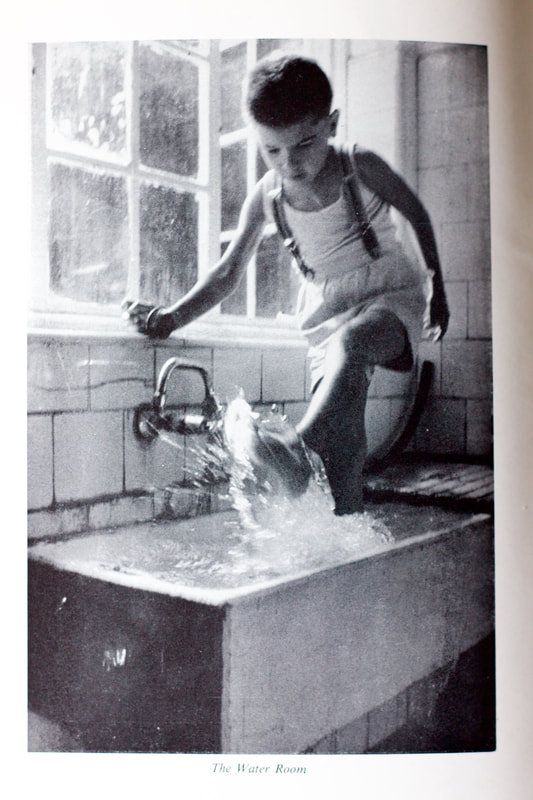

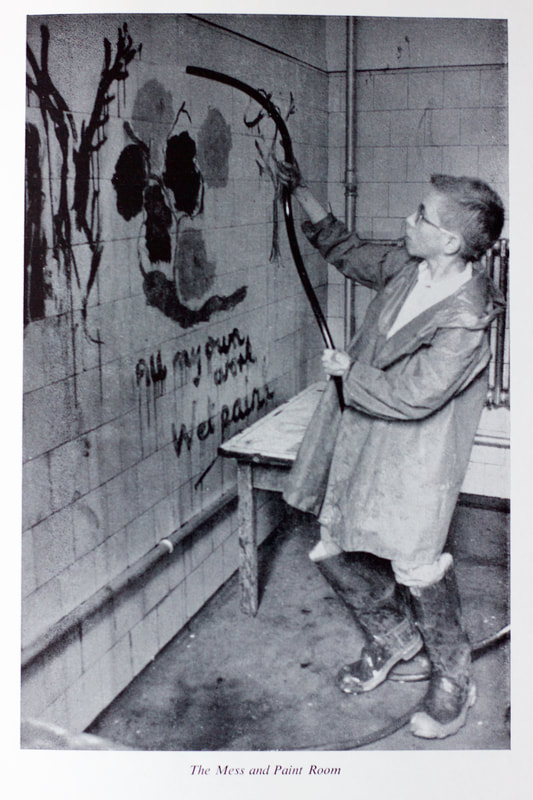

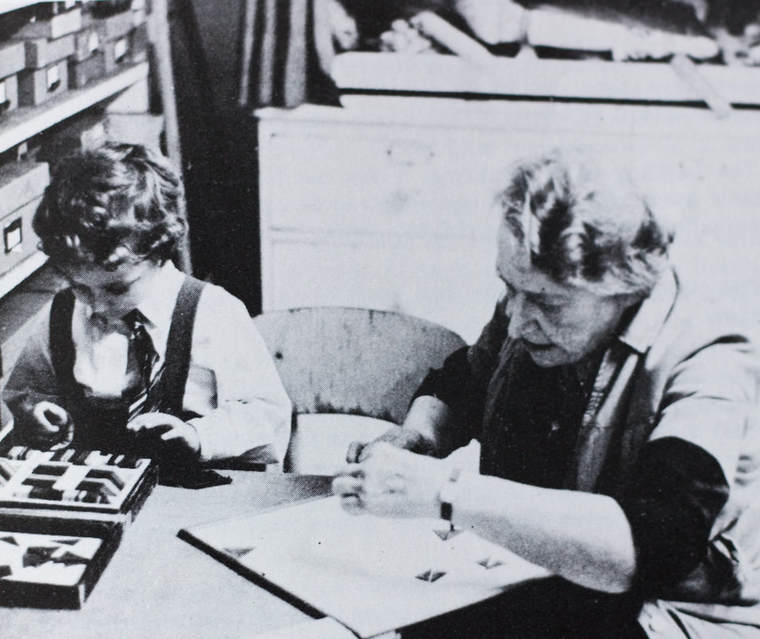

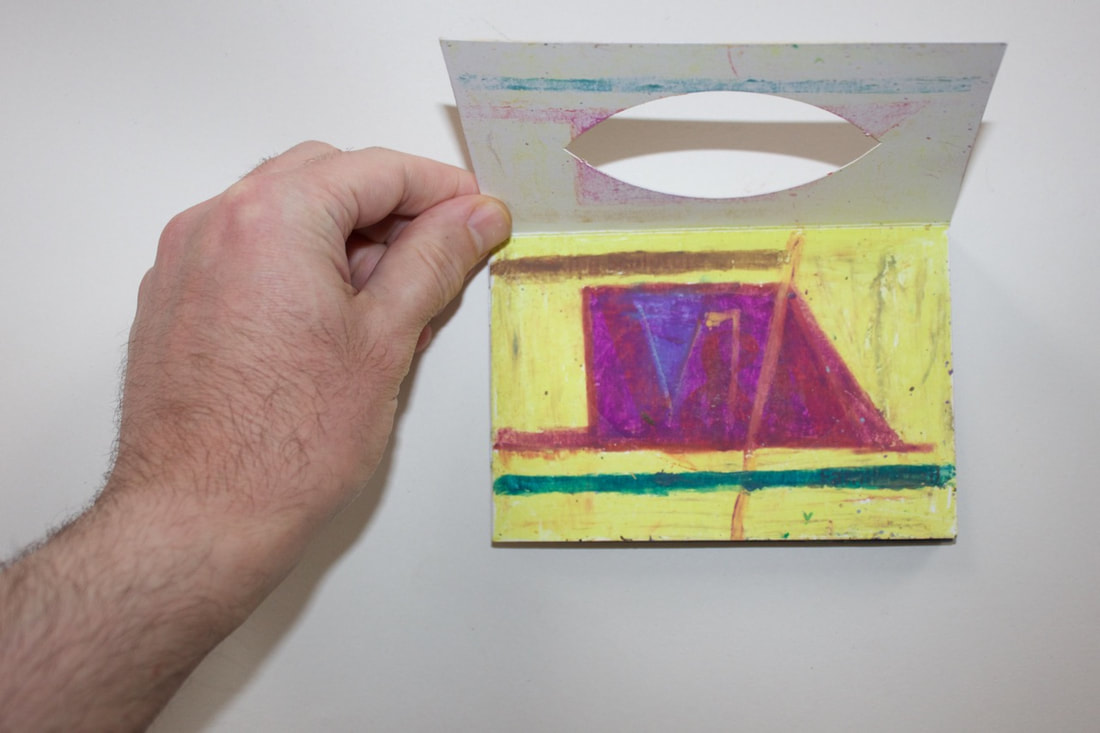

Margaret Lowenfeld (1890-1973) was a pioneer of child psychology and play therapy. She was able to make creative connections of the highest originality. The child-centred philosophy she developed and its process of therapeutic play-making was the culmination of many factors: central to these being her experience of children traumatised by World War One; and also her observation of the colourful patterns in Polish folk costumes. Her work and legacy has influenced my thinking and art practice, both before and after the Grenfell Tower fire that occurred on 14th June 2017. I have always used a model of art making that was rooted in play and non-verbal processes of communication. I was able to use this during Art for Silchester, a seven month residency that has just ended at Silchester Estate. I worked with residents and children who live across the road from the tower and each of whom are coping with the tragedy in different ways. During these sessions, we made large scale drawings and ceramics which were indirectly connected with the therapy of Margaret Lowenfeld, who first started her work in this area of North Kensington in the late 1920s. I also recently met up with Margaret Lowenfeld's great nephew, Oliver Wright, who is one of the therapists working with the NHS in providing support to local residents traumatised by the fire. But this blog is an interview with Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock that was recorded from July-Sept 2018. She is retired from practice, but was trained at The Institute of Child Psychology in the early 1970s and was the leading proponent of Lowenfeld Mosaics as applied to child psychotherapy. In talking about her life and work as a Lowenfeld therapist, I was also able to open up and have a reflective space to think about my own feelings, my inability to voice them over the past year and how I am now moving forward as a person and artist. A war child in Hong Kong and China I was born in Hong Kong, a British colony in 1935. My parents were both teachers. When they graduated from university they started their own school based on my mother’s ideas. She was an intuitive teacher and had this notion that when you teach a child it isn’t just the teaching that counts. It is also about the child. In Hong Kong during the 1920s and 30s that was a rather unusual idea. When the Japanese took over Hong Kong they changed all aspects of our lives including our consciousness. When my brother was born, my parents decided they didn’t want to live under the Japanese and they went to Canton, China. We had nothing and squatted in an empty house. My parents had to have two jobs in order to have enough money to feed us. I was left on my own and wandered around quite a bit. I once stumbled across this march. Being small and very inquisitive I wiggled to the front. There were two Chinese men being executed by the Japanese. The whole crowd watching was Chinese. As soon as one of the prisoners stepped forward the crowd cheered. Then a band of soldiers tried to shoot him but he kept on spinning and it took a long time for him to fall. The crowd just kept on cheering. I was an innocent child and didn’t know anything about politics, but I thought: fate was going to show the people this was a good man. Children see things that they don’t understand and they have to make some sense of it. I didn’t see him fall and I thought he was a good man. That thought came to me as a child and I only found a word for it, patriot, when I came to England. So the words come much later in my understanding. After some time my father returned to Hong Kong to see when it would be safe for the family to return; leaving my mother, my baby brother and myself in Canton. It was during that period that I met a Japanese boy. The meeting was very curious because the Japanese boy was trained to think that Chinese natives were bad. I was walking with my brother in my arms and he threw a stone at me. It hit my elbow and I got really angry. I rushed home, dumped my brother on the bed and went back. I said you hit me and I’m going to hit you back. It was very foolish of me because I was eight and very tiny. He was about ten or eleven. He was so shocked because I could speak Japanese. He then said: if you can speak Japanese, you must be educated and civilised. So he wouldn’t fight me. We became friends and I learnt even more Japanese from him because I didn’t have anyone else to play with. My mother knew nothing about this Japanese boy because she was so busy earning our rice. Just meeting him prevented me from thinking that all Japanese were bad. This later fed into my understanding that all group prejudices were a generalisation of personal experiences. Life is not simple. It’s not reasonable. It is not governed by things like - if this happened here, then that happens there. There is a war, but for the individual child all kinds of experiences are possible. These were war-time relationships and had no consequence afterwards. But even now, I sometimes wonder what happened to that Japanese boy. A scrambled education and life in post-war England We came back to Hong Kong in about 1946 with a wheeled cart and the little luggage we had. My father had found a flat. I continued to look after my brother but not for long. My mother wanted me to go to school, but I had missed three years and so my Chinese wasn’t up to standard. So she decided to put me into a school where the teaching was in English. I didn't know any English. I was 11 and had to spend the first few months writing nothing but lines: I MUST HAND IN MY HOMEWORK. I was always semi-bottom of the class. In my school leaving year, I failed in everything because I couldn’t be bothered to study. It just seemed too difficult. My mother asked me if I would be happy to be a street sweeper or a secretary. It was then that I realised the value of an education that enabled the individual to have a wider choice in adult life. So that year I started to study. When the exam results came out they would be published in newspapers and the top 50 students would get scholarships. I got one. That was such a shock. I later discovered that my mother had been saving money for my education. But my father would always say - don’t overeducate your daughter because she won’t get a husband. You can see there were two very different philosophies in the household. But in the end he was very proud of me. At university I knew I had to study hard. I studied political philosophy. I did psychology, I did logic. All the kinds of things you don’t get at school. Wonderful. I was just enjoying my life. I wanted to become a librarian because I love books. The only post-graduate course on librarianship in the whole of the UK was at University College, London. They had lots of foreign students but they only accepted people with First or Upper Second Class honours degrees. I was very lucky to get in. They said do you have a classical language? I was very cheeky and said I have Chinese. I didn’t tell them that I only studied basic Chinese. They said, they didn’t have a Chinese student and we’ll take you even if you haven’t got any Latin or Greek, nor German or French. This must have been in 1958 and it was a one year intensive course. During the second term I had pneumonia. I was staying in a university hostel and the registrar who was looking after me thankfully had a nursing background. When I went to take the exam, there was no way I could pass it. I passed one paper. I failed the other. They said we really want you to pass, so come back. But I had no money and the course was teaching you how to catalogue Latin manuscripts for working in a university library. It was not for public libraries. I thought this is all too alien and that I couldn’t continue. Domestic life and the discovery of a vocation I then thought I might enjoy teaching but got married and had children. I had to learn how to be a housewife and mother in England. All without any help. What I discovered was that I could talk to another PHD person but I didn’t have any ordinary language. My husband was working in the Midlands as a salesman and he travelled all over the place. We were living in a new estate which had just been built and I didn’t know anybody there. The biggest town was Bromsgrove and that was at least three miles away. We had no telephone. My husband just thought: this is your domestic scene and he decided to have a mistress. I said, this isn’t right, is it? We can’t carry on together when there’s no connection. So I was in a terrible bind and came back down to London. Then he followed with the children. I had to get a job. As I was the one who left, I had to help with the family finances and earn enough so that my husband could have some of my earnings as well. Then I met Jasper. We discovered that maybe we should get together. Jasper and I were married for 46 years and the children lived with us. The children have always thought of him as their dad. During this period I also had personal therapy. The therapist said to me: I can see that you don’t want to be a librarian anymore or a teacher. Do you have any ideas? I said: yes, I want to sit in that chair (pointing at her). I’m going to be a therapist who sees children. First Mosaic made by Therese upon arrival at the ICP, 1969 The Institute of Child Psychology (ICP) I went to Hampstead to visit the Tavistock Clinic. They said you can’t see anybody because they are seeing children and they are in private practice. I said: how do I find out about your training? Well, you’ve got to come to attend our courses. How long will this take? The lady said: it depends on the individual but it could be 4 or 5 years and the student would need to have personal psychoanalysis as part of the training. I just didn’t have the time or money for this. So then I went to visit the Institute of Child Psychology in Notting Hill and they said: Dr Lowenfeld will see you, but she’s with someone else at the moment. They gave me a Mosaic to play with while I was waiting. It was a very clever idea. I knew nothing about what I was doing. It was fun. I made this tree and plane in my Mosaic. In hindsight, I realised this encapsulated my journey and life here in England. The tree was me growing up and the potential to develop in this country through the course. What I didn’t know was that they kept records of all Mosaics and when the Institute closed, I looked through the records and rescued my Mosaic. Margaret Lowenfeld was one of the first child psychiatrists who was interested in finding ways for children to express themselves without only using words. She thought about what happens to a child between age zero and seven. How do children of that age think? She realised that what children perceive is multi-dimensional and cannot be put into words that are in linear time. The child has many ways of seeing the world and they formulate ideas through their sensorial experience. Lowenfeld had this notion that they do it through pictures. So she had this idea of picture thinking in the late 1920s and 30’s and pioneered the use of Mosaics and the World Technique; the latter known more generally as the sand tray used with miniature toys in dry or wet sand. These are play and language tools for the children to express themselves without relying solely on words. Lowenfeld opened the Children's Clinic for the Treatment and Study of Nervous and Difficult Children in North Kensington in 1928. This offered a unique form of therapy for children that did not exist anywhere else in the country. Before the Second World War, the clinic was very well known and mainly supported by private funds. Lowenfeld wasn't charging the local people very much because this was a poor area and she wanted these children to have the use of these facilities. Photographs of Margaret Lowenfeld and children using the World and Mosaic. There was a change of name and The Institute of Child Psychology relocated to 6 Pembridge Villas in Notting Hill Gate. The Institute had facilities that were exclusively given over to the self-generated play activities of children. There was a big basement to the house where the playrooms were located. The children could play ball and use climbing frames. There was a trunk on wheels which the children could hide in. Another trunk had clothes and hats and objects. This was used for dressing up and often lead to dramatic play in innovative ways. There was also a painting room where the children could paint on the walls. You could hose off the paint with water to obliterate the child’s painting should the child not wish for the painting to be kept. There was also a water room where you could have water and toys on the floor and we all had to wear waterproof clothing and wellingtons. The older teenagers might think that playing was too childish and so they could talk in what we called the Quiet Room. Occasionally we would take a Mosaic in for them to use. The Institute always had a file for each child’s therapy work that included a recorded copy of all their Worlds, Mosaics, drawings and paintings. At any given time you might have 6 therapists with their children in the playrooms. We worked together as a team, often helping out by observing other children when the therapist might have missed out on some aspect of their child’s action. It was also a very demanding training. I could write about 12 pages of notes that documented what my child did in any given session. We would never impose a point of view or interpretation of their play. The aim of all this was to allow the child to express their point of view and feelings through play. I started my post graduate course in 1969 and this lasted three years. We only had two new students per year. We had daily supervision, but on Tuesdays and Fridays we had two hours of group supervision to discuss what we called Corporate Cases; these were the children who were not solely the patient of a particular therapist. In the student’s last year, they would be supervised by Lowenfeld. I liked doing the Mosaic and the World with the children. It could take two sessions to do this because sometimes children take forty minutes to do a Mosaic. I prefer to use the Mosaic because they have a progression or a regression and they tend to be linear. I don’t interpret the mosaics. I talk to the children through it and then sometimes they will tell me what it means. The Lowenfeld therapist always had to be lower than the child. I would sit in a chair that is the same size as the child. I’m lucky because I am fairly small anyway. Lowenfeld was not psychoanalytical. She said her ideas were only just one philosophy and so we were taught about Freud, Klein and Jung. She said you will need to understand what other professionals might tell you about the child under consideration. The Institute had a child psychiatrist, an educational psychologist, a social worker and a West Indian social worker, as the area the ICP was in had a lot of West Indians. I think I had an excellent training and it never troubled me that the psychoanalysts thought I was not trained. Lowenfeld had set up a proper postgraduate institution and awarded postgraduate diplomas. They had an academic board who oversaw standards. That’s why I got a student grant because it was properly recognised by the national Education Department. Case studies and sexual abuse I remember this nine or ten year old girl who came to the Institute and just stood rigidly. She believed that her back was made up of one bone and that she couldn’t bend her body. She only spoke in whispers, not wanting to expend her energy reserves. She was worried that she would die and had stopped eating. I said to her: do you know what our back is made up of? She said there’s a bone there. I said your quite right but there’s not just one bone but many bones. I’ll show you. We had these models. I got her the skeleton and I went slowly down the spine guiding her hand so she could feel the knobs. The first treatment objective was to get her to learn about moving freely. We often did body work because, for instance, many girls didn’t understand about menstruation. There was also a fifteen year old Indian girl who was very unhappy and wasn’t eating. She told me she was going to have an arranged marriage but wanted to go to university. The parents felt that any further education would be unnecessary since their aim was for their daughter to get married immediately after leaving school. To enable her to get into university, I said: you have to go to the library rather than home to do your school work. Sometimes therapy is being pragmatic for people to get out of these difficult situations. You’ve got to offer them a solution that will relieve them from that. Only then can it be analysed and if the child wants it to be. What happens if the daughter is expected to sleep with the parents? I said okay. Which side of the bed are you sleeping? I’m sleeping on the right hand side. Who else is in the bed? Mummy is on the other side. So I asked who is in the middle. That’s daddy. I asked her how she liked the arrangement. This is a thirteen year old girl and was a case of sexual abuse. There are girls who I can discover their issues through their World Play or like that girl who did a Mosaic. She kept on shoving Mosaic pieces in between other pieces. I said sometimes that happens to older people as well. She nodded. I said: it also happens to girls. What you need to do, to stop this, is to tell an adult. There’s a law that allows me to talk to you about this. I was getting somewhere with one child who was telling me the parents were abusing her. The parents then stopped her coming to see me, saying Mrs Woodcock’s English is so poor that my child can’t understand her. You can’t argue with that. What I said to the girl was: I’m sorry this is your last session because your parents are not happy about you coming. I said: you know what the problem is. You are fifteen and by the time you are sixteen, you can leave home. That was all I could say. Perhaps there are limits to the therapeutic process. Lowenfeld never talked about sexual abuse at all. You would think she never knew about it. But you see nobody was talking about it at the time. The biggest change I saw over these years was actually having abuse recognised and also the legal aspect of myself and social workers having to report it. I thought that helped me to talk to the children. By law, I had to report this and some other professionals were then able to help the child. In Summary I am extremely grateful to have attended the course at the Institute of Child Psychology. It enabled me to help children by using the World Technique and the Lowenfeld Mosaics. When I graduated in 1972, I worked for the NHS and child guidance clinics in Newham, Haringey and Barnet. Both Haringey and Newham were multicultural and deprived areas. I didn’t actually want to work anywhere else. That was a personal choice. I wanted to work with a variety of children including the poorest. I saw my last case in January 1995 having worked as a Lowenfeld therapist for over 20 years. A selection of my work will be housed at the Wellcome Library as part of the Margaret Lowenfeld archive. Expressing the shape and colour of personality: Using Lowenfeld Mosaics in Psychotherapy and Cross-Cultural Research By Therese Mei-Yau Woodcock, Sussex Academic Press, 2006. Photographs and text kindly reproduced: © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library. Postscript Let us end with Margaret Lowenfeld's account of the first day the Clinic opened on Telford Street in 1928. This was in rooms hired from the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre (aka birth control clinic) where Margaret's sister, Helena Wright, worked as the Chief Medical Officer: The two rooms that allowed for the Clinic's work consisted of one opening direct on to the street, which we used as treatment room for the children, and a second room opening out of it. Here records could be made and kept, parents interviewed, biomedical investigations carried out and discussions conveniently held between myself and my colleague. Money was short so the playroom furniture began as one table and three chairs, one of them a fireside chair placed between the diminutive gas fire grate. The play material was kept in the second room and carefully selected for each child who came - it was too precious to be indiscriminately displayed. Later a second table was added for the children to paint on, the first round table remaining in the centre of the room. A scene in which this table figured later won us our crucial friend. The first child who came was the "bad boy" of the neighbourhood, abominated by the shopkeepers. He came by himself and I do not remember seeing his mother. He was defiant and silent but remembering the Polish children, I left a French painting book - these were lovely (good ones being practically unobtainable in England) on the table with water and painting brushes. He seated himself with his back to the centre of the room and studied them. Half an hour later I stood silently in the communicating door watching him. His concentration was intense, he breathed excitedly and - schools being different in those days - I found later this was the first time he had the magic of colour in his hands. Every day the Clinic was open he came, and slowly began to talk. By that time I knew his attendance at school was erratic and all efforts to improve this had been defeated by his silence under questioning. We made a pact together: more regular attendance at school on the days and times the Clinic was not open, and fresh paints and painting books when he came. It was from the school we heard later that a different boy had slowly emerged - complaints against him ceased. One day he brought a young friend with him and we knew we were winning our way in the neighbourhood. Constantine Gras making a mosaic, with from left to right: red beacon, tower from black to green to no colour; myself draped in those colours; and a key, a set of arrows pointing to me, the tower and Thérèsa as witness to the mosaic. "I felt I needed something in addition to the tower and me. I don't know what it is. Maybe it's a signpost trying to direct me or others, but everything is shifting apart again over time. Then I step back and look beyond the tower and me. I want to get a sense of the overall space and how these objects function within that space. Can I possibly create something that is aesthetically or emotionally satisfying? I am trying to make a work of art. I'm not sure if that is right." "Yes. You are an artist. You cannot escape that." "I was hoping that I might, but I don't think so." "You won't be able to escape yourself, will you!" "No. No." At Play In The Ruins: A Lost Generation

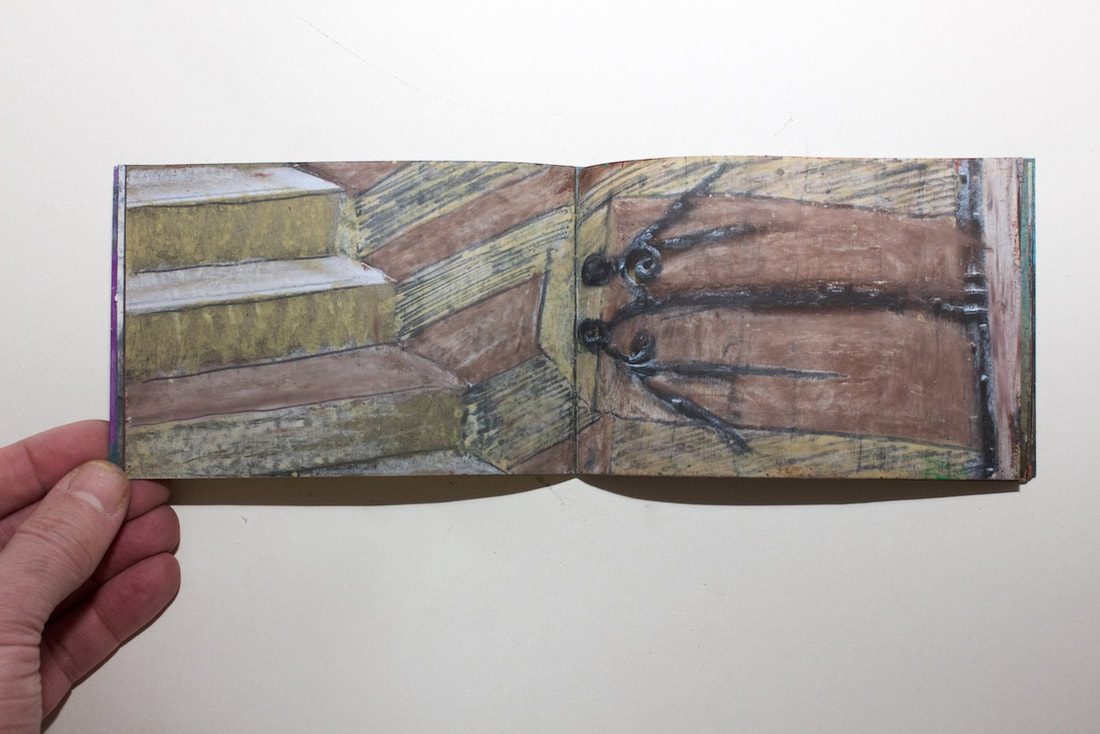

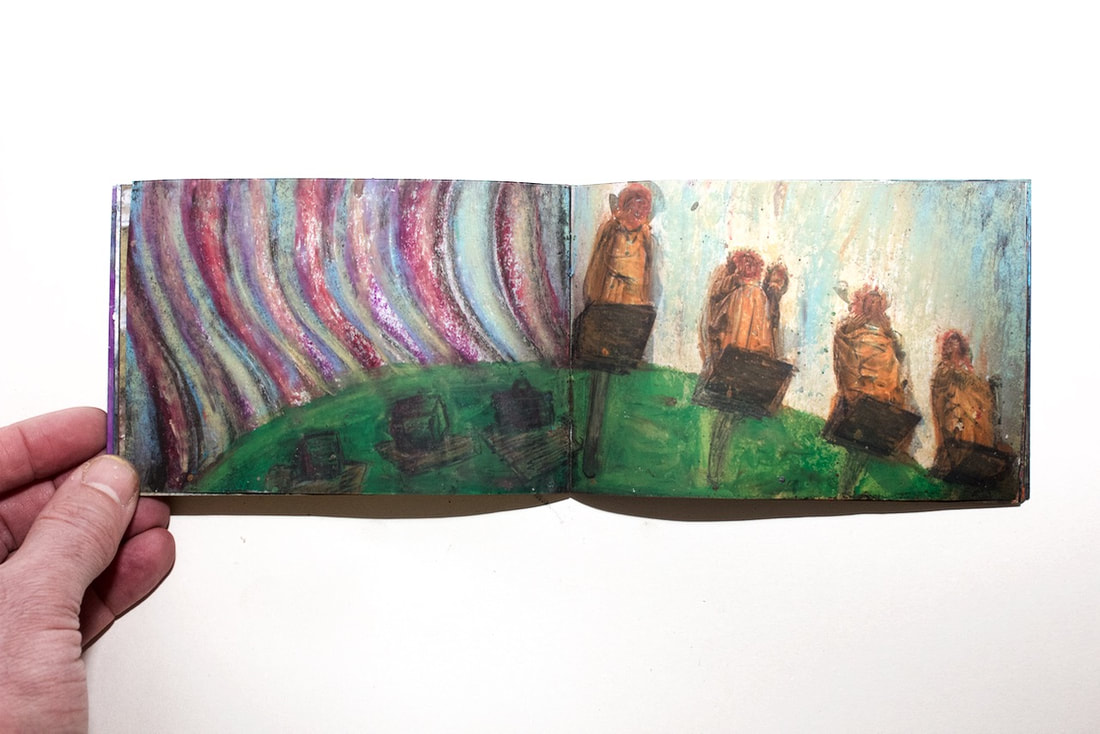

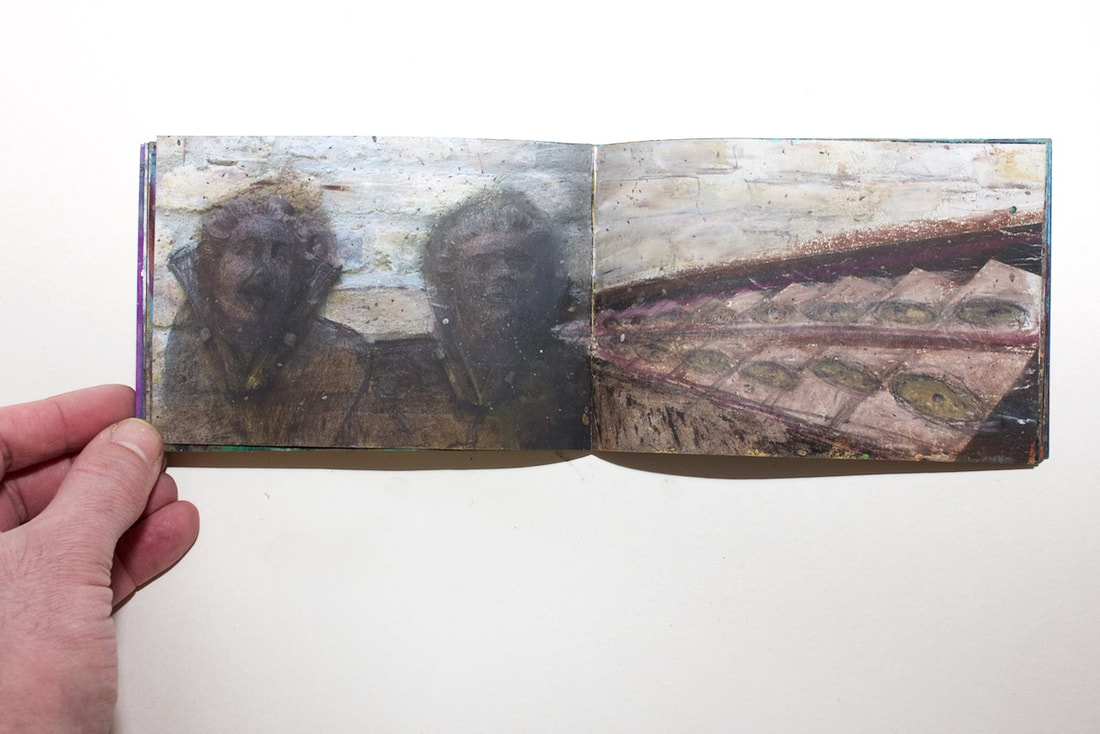

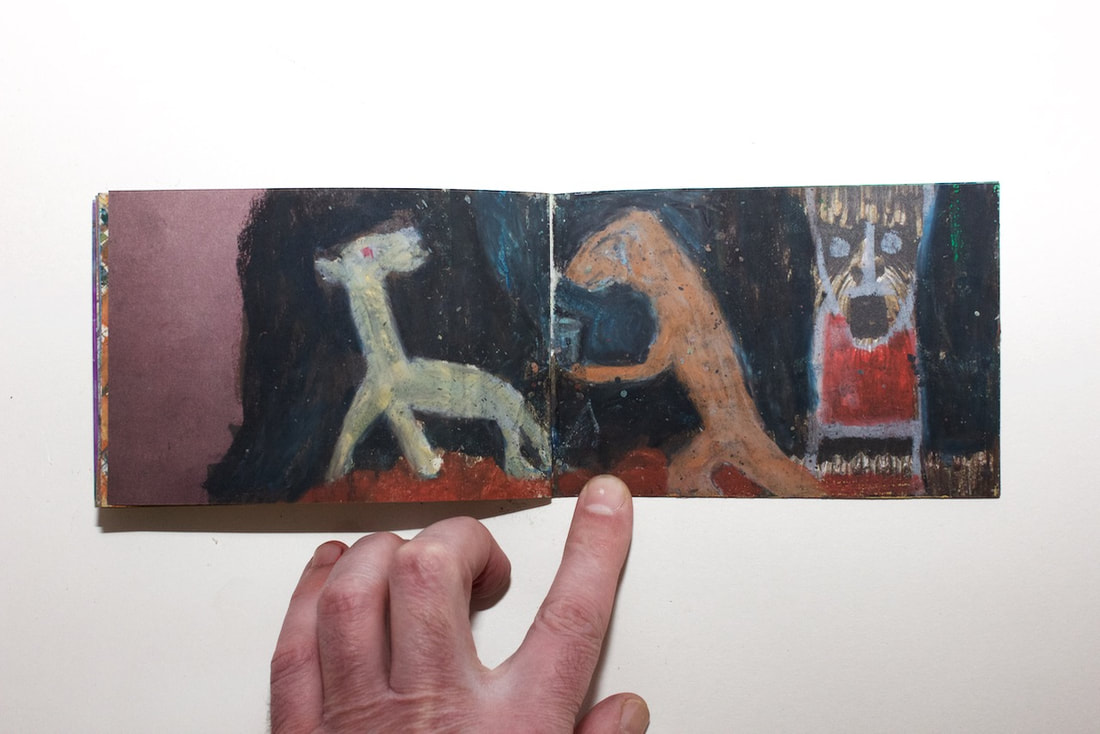

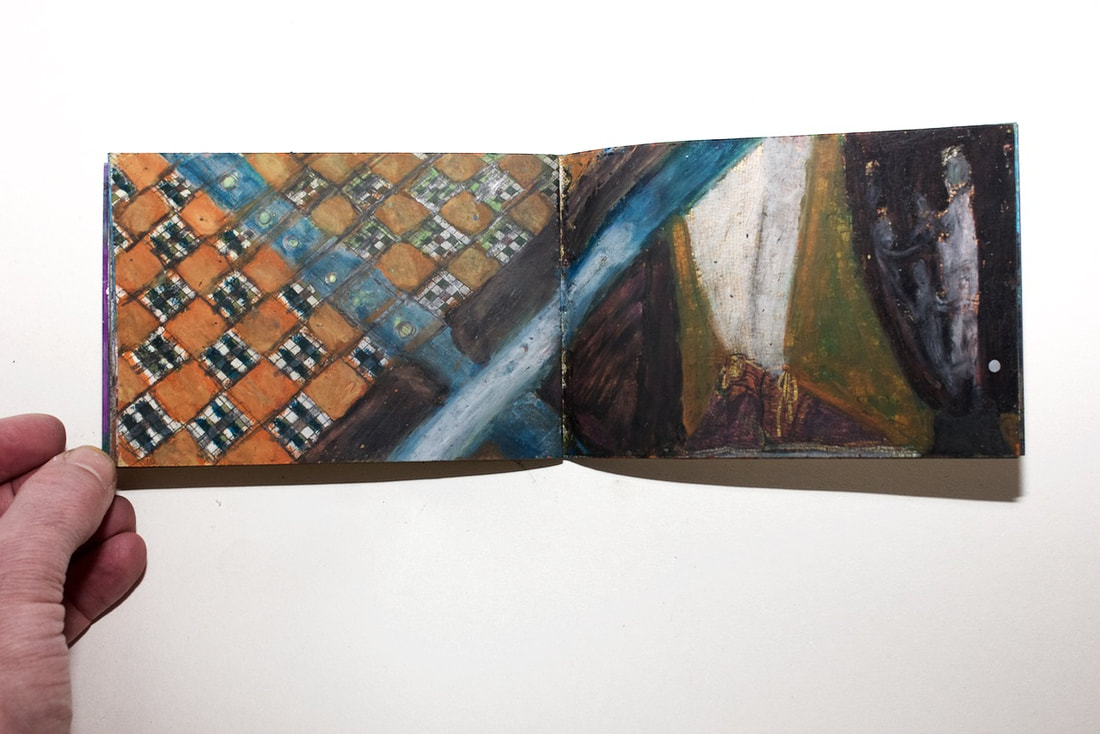

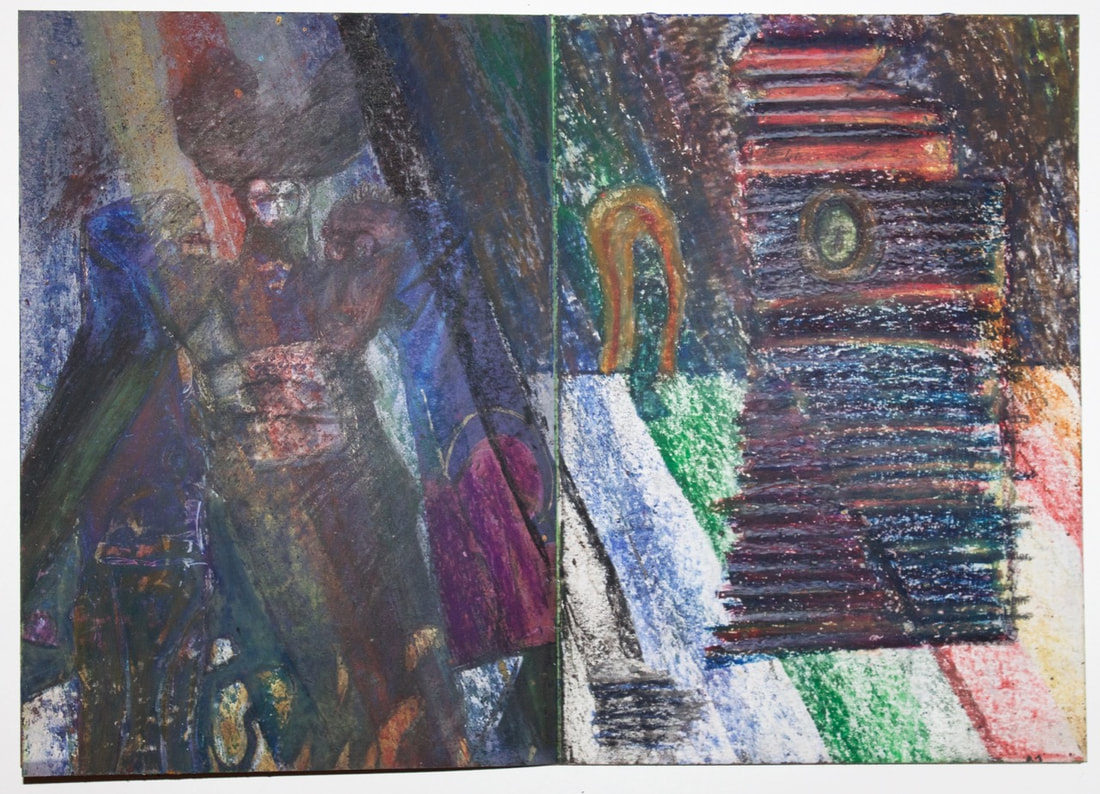

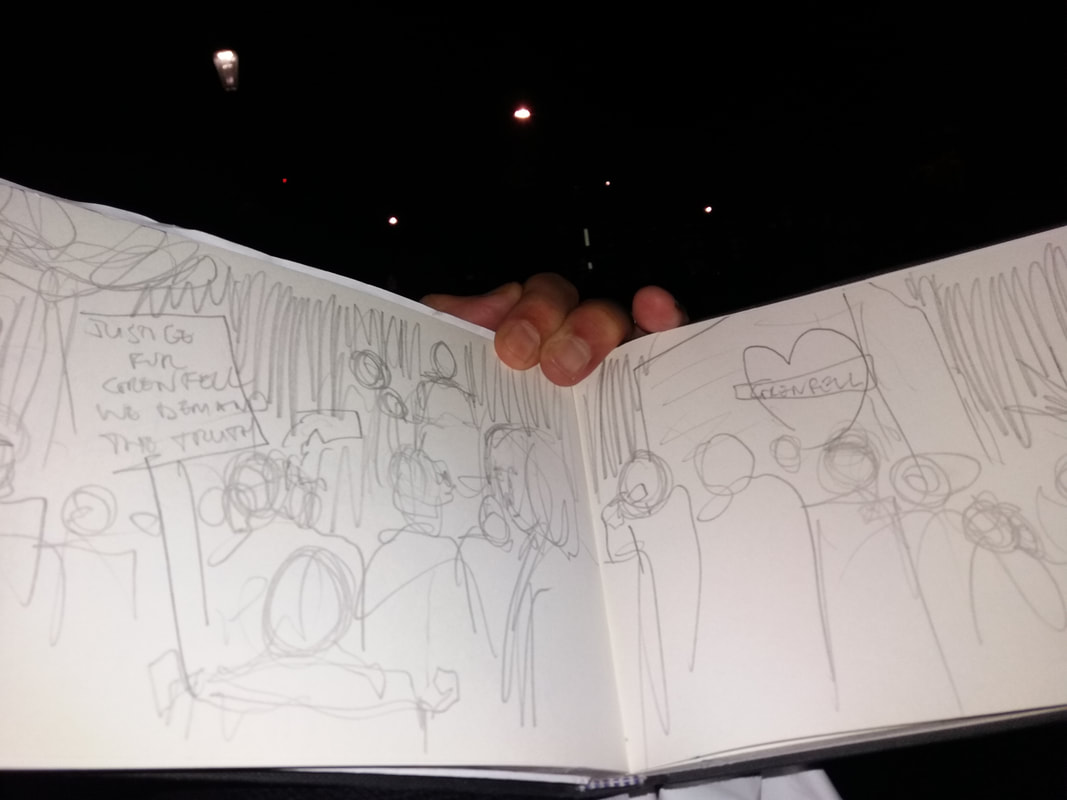

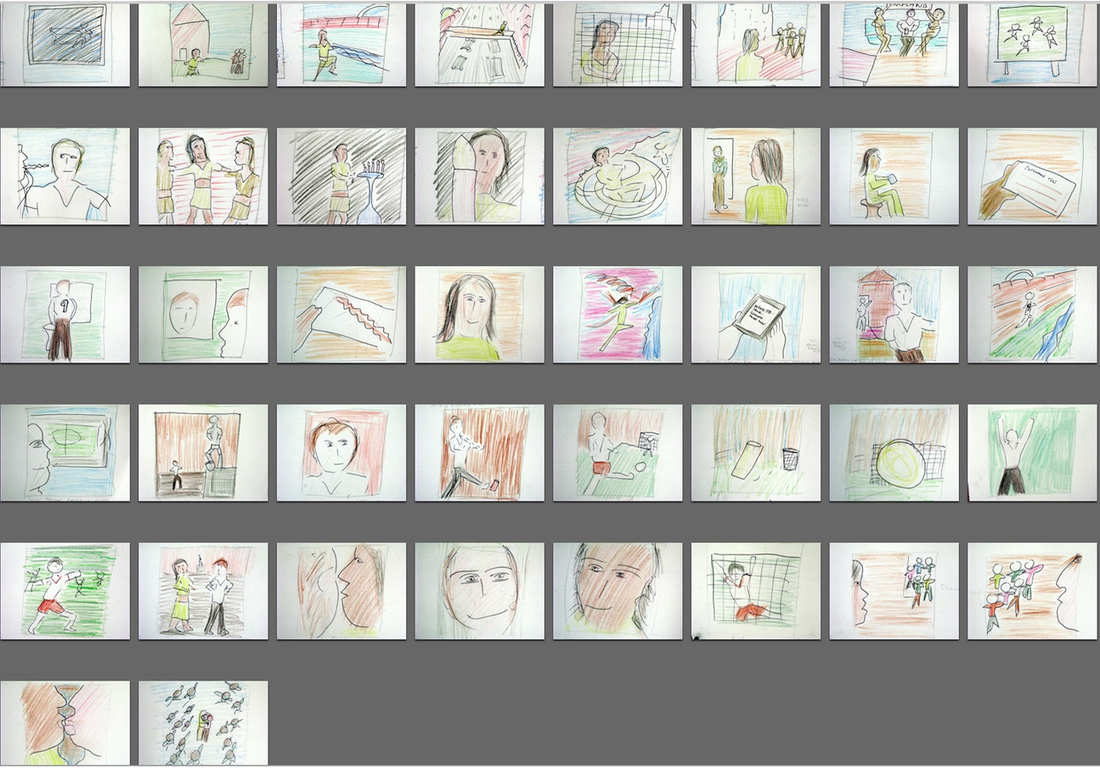

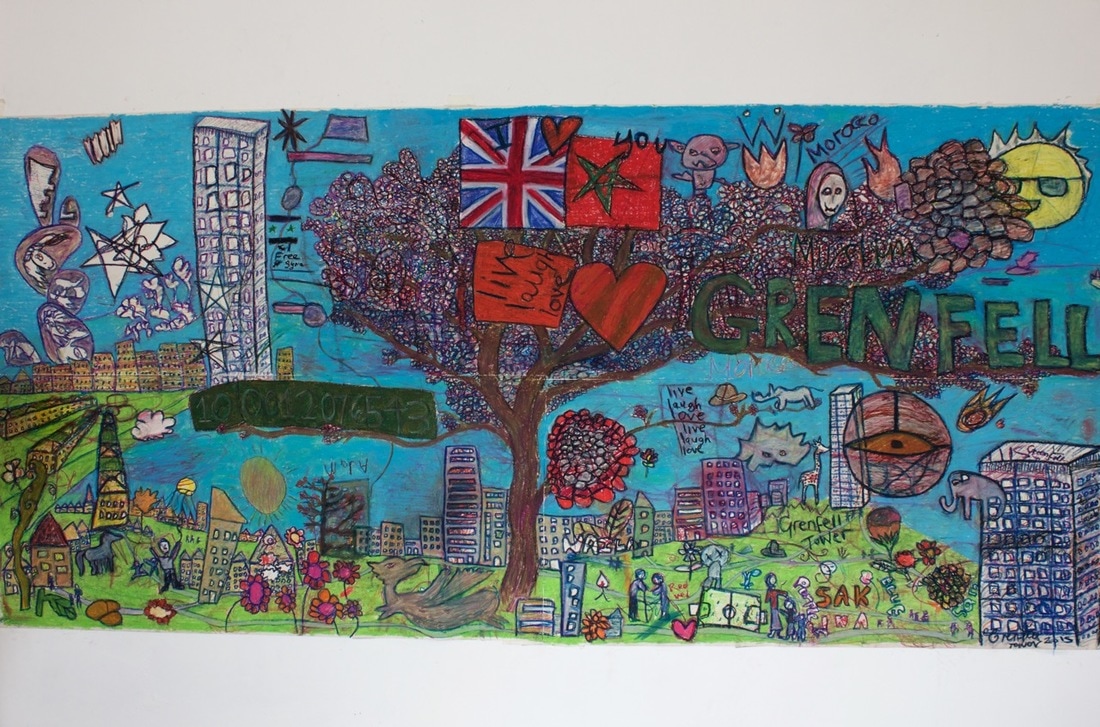

oil pastels, 33x24" 19 Dec 2016 Artist's comments on the reverse of the drawing: Starting off with abstraction, but thoughts turned to Lowenfeld sand play (Sand Face in the picture) and childhood. The news on the following day. The battle and now the desperate evacuation of Aleppo in Syria. One of the defining media images of the year, Osman Daqneesh pulled from the bombed building. His haunting stillness in the midst of horror. I have struggled to talk about Grenfell because I am an artistic "witness." I made a deep connection with the estate and its gardens several years before I started working here on an art residency. When I was officially contracted to produce a film and mural in 2015, several residents kindly opened their front door and hearts to a stranger. I navigated a delicate path between authorities and residents at a time when the latter were in dispute over the tower’s regeneration. After the tragic event in June 2017, I handed over all my photos and films to the police as part of their criminal investigation. I gave a witness statement. As we try to understand what happened at Grenfell, artists and film makers will all have a challenging but important role to play alongside the media. I’m trying to objectively recall how I approached making art on the estate when I was commissioned by the TMO (Tenant Management Organisation) to create a tiled art work and short film. The TMO were impressed with my V&A Museum and RIBA funded residency on Silchester Estate. I convinced them that an open-ended, durational process would work far better in delivering the outcomes rather than the original two weeks envisaged. As it transpired I was on the estate for approximately 1 year 2 months. When the time is right I will talk about the film, The Forgotten Estate, in more detail. The original plan was to design a large tile art work to cover an area approximately 3.6m wide by 2.2 m high in the newly formed ground floor entrance at Grenfell. This was to be created with the residents and children of the tower block. I was given a completely free brief as regards design. I decided to use large scale drawings as the blueprint. But as the drawings were so impressive in their own right, I decided to just stick with that as the completed art work. In total, 4 large scale drawings were made in the temporary lobby, on the elevated concrete deck just outside the tower and during the Grenfell fun day. The design for the art work was inspired by the classic blue and white willow pattern used in pottery. I was constantly sketching in the ceramic gallery at the V&A where this pattern had caught my eye. I always envisaged using an image of Grenfell tower in the completed design and perhaps to have this framed by an equally large tree. I saw a flock of birds in flight as representing the residents energised by their newly renovated building. The sessions with the kids would allow space for their own images and experiences to be added. That was the plan. As it transpired, the most successful drawing was realised at the Fun Day. The Grenfell Fun Day on 30 May 2015 was held mainly as a form of respite from the conflict taking place during the renovation. I was invited to attend and hold a workshop. A teenager looked at a blank sheet of paper. "What do we draw?" "Absolutely anything you like." Most children had the desire to draw or write what came naturally to them. The tower block they lived in. A girl picked up a leaf and sketched this. Animals started to appear. One wrote the memorable words: live, laugh, love. The cultural identity of the children also became a point of self-reflection with a Moroccan and British flag. The outline drawing in oil pastels was made by approximately 20 children and I then coloured it in. The art work then fell into a state of limbo. I had shown it to the TMO who were happy and also took it to a residents meeting. This would prove to be my last engagement and memory of the estate in May 2016. In the middle of that meeting, shortly after I had talked about the art work, one of the residents had challenged me over my film and this annoyed another resident, whose tense relationship with each other I had observed before. They then had a fight, then and there, in the meeting at which children were present. It lasted for about 5 minutes. Blood had to be cleaned off the walls. I believe they shook hands shortly after. I could understand how the residents were wanting to get on with lives after the huge impact of the building works. But the TMO? Why didn't they contact me again to hang the art work in Grenfell? I can only assume they were not pleased with the way my residency had developed, especially in terms of the film project. I held onto that art work for a year. After the fire it assumed importance as a visual and textual testimony to a destroyed community: Live, laugh, love. I'm pleased that this has been handed over to Grenfell United and is in the new community space for survivors and the bereaved. I have now started work back on Silchester estate across the road from Grenfell. After the anniversary of the fire, we will hold an Open Estate Garden weekend on the 30 June and 1 July. This will display the art created by residents. I have plans for a dance or performance piece facilitated by Dance West, although this might have to be staged later on in the summer. Over the years I have self-published photo books as well as making hand crafted books. I have increasingly turned to the latter as a means of reflecting on my engagement at Lancaster West and on the people I met and befriended. I am constructing my own self-questioning narrative. Did I make the right decisions in terms of my engagement? How will my imagery and art work be reproduced and the film footage help with any inquiry or criminal proceedings? Above all, how can I help the victims and community? I know that this was a "voiceless" community that nobody really listened to. I have also thought about my interaction with the press as they strive for the dramatic and poignant human story as well as the political message behind Grenfell. During the previous 9 months, I have developed an inner artistic voice that has kept the media, by and large, at arms length. These books, as I turn the pages, are part of my opening up. Imageless and Voiceless Booklets, 32 pages each, 2018 Oil pastel drawings, 5.5 x 4 inches Just heard about Grenfell Tower. Ghastly. What on earth went wrong? I was wondering if we could get this picture to do a story on. I would be very grateful if you could give me a ring as soon as possible to discuss an article I am working on for this weekend. I am the Dangerous Structures surveyor on the tower following the incident. If you were involved in the original construction it would be good to talk or meet you to discuss how certain elements work together. Constantine, various journalists have tried to contact me but I am not responding, so I would appreciate your confidence and not pass on any of my contact details. I don’t want him to think I’m stalking him! I don’t actually need him to discuss the fire. It is the building we are interested in and the original vision. One thing I'd say is that if we want to tell this hugely important story then now is the time, before the world moves on to the next headline. We have three million readers worldwide, a lot of them policy makers. Do please let me know if you change your mind. I am contacting you in relation to a live broadcast we are holding tomorrow evening. The event will consist of an audience of local Councillors, residents, firefighters, volunteers etc. If this is something you may consider being a voice for, please let me know. I do totally understand your reticence to give opinions on the matter, but could I trouble you with a quick question – do you know of any nearby towers that have a similar interior, i.e. common parts and layout? We are not tabloid journalists in for a quick story. We do very considered films on very difficult and distressing subjects. Thanks for the clear details in each of your blog posts. In an attempt to lend a little assistance from afar, a group of us have been building up three Wikipedia articles [[Lancaster West Estate]] [[Grenfell Tower]] and [[Grenfell Tower fire]]. Please go to these pages and tell us of any inaccuracies. I would rather use an image that speaks to the life in the community rather than awful images of destruction and tragedy to publicise the auction. The last thing I would want to do is appear to sensationalise the suffering of so many people. If you do have a change of heart, let me know. We would happily make a £200 donation to a Grenfell charity for use of your images. Dear Mr Gras, the V&A have been contacted by the Detective Constable from the Art and Antiques section of the Metropolitan Police in connection with the Grenfell Tower enquiry. She is working on the construction side of the investigation and has been tasked with identifying and contacting every company who may have information about the construction or refurbishment of Grenfell. I'd like to ask some questions on a positive note. I'm not press or politics. I knew that building was fundamentally safe. I'd really appreciate some answers regarding.... Sorry I can't say here.

An exceptional ceramic object was made recently at one of the workshops I'm running at Silchester Estate. Cerys Rose made a tower block to begin with and then added this onto a base structure. But it was what she did next that was truly remarkable and inspiring; she took a conceptual leap of faith that is advanced in one so young. Cerys playfully added on what appeared to be flying buttress supports. I then asked her to reflect on what she did: "My art piece is based on protecting. It is a peel, for example a banana peel. When it is peeled, it is not protected. When it is not peeled, it is protected." So much for flying buttresses! Cerys was on a more imaginative wavelength. At the time, I didn't want to ask her whether the banana protection of her building was in reference to Grenfell tower which looms large over all of us in the area. Cerys's friend, Sina Michael, another very talented artist, had made a more direct reference to this in her scale model ceramic work of the five high rise tower blocks that dominate the local skyline. As residents at Silchester Estate shape clay into objects real and imagined, sublime and surreal, my mind wanders back to two previous ceramics projects. One that I have blogged on and another that I have repressed from living memory, until now. Leo The Last is a 1969 film that I used as a meditative tool and to create art with residents of the estate in 2015. This wild and experimental film, tapping into the counter-culture of its era, has mythic qualities for our patch of North Kensington in London. It is a true Notting Barns film made on the plot of ground and in the soon to be demolished “slum” houses on Testerton Road before they were developed into Lancaster West estate and Grenfell tower. Leo is an aristocrat who has moved into his million pound white house that is cheek by jowl with the black painted properties of his down at heel Afro-Caribbean neighbours. Leo becomes radicalised, albeit in an idealistic fashion, after he discovers he is the slum landlord for the area. The film ends with a community riot that burns down his house. Leo is philosophical about not being able to change the world, but we can change our street. After screening the film on a 35mm print for the general public, a group of residents went to the V&A and created houses and other structures under the supervision of ceramic artist, Matthew Raw. I was then able to use these to re-create the road that you see in the film. This was displayed at the museum as part of my end of residency display of art. In a prophetic parallel, Cllr Rock Feilding-Mellen, had the opportunity to become Leo. Rock is not a film character, but a Tory Councillor of aristocratic origins, who moved into a posh property that was located across the road from Lancaster West estate. But there was no sense of him becoming radicalised by his neighbours or attempting a more modest community engagement here. His job as deputy leader of the council and head of regeneration was to mastermind the plans for the systematic regeneration (i.e. demolition and disruption) of Silchester Estate. This was at the same time he was directly responsible for the modernisation of Grenfell tower. You cannot watch Leo The Last now, without making these poignant connections. When I was inviting residents to make ceramic houses and reflect on social history and its relevance to the contemporary world, I had little idea what was about to happen in North Kensington; or even how that might radically change me. I feel my art engagement here was sympathetic to the local residents and their sense of place. However, if we go back a few years to 2012, another ceramic art project was artistically and socially less successful.

I was running several art projects at the time around the theme of water and one of these had Cultural Olympiad funding. It was for an 11th century motte and bailey listed heritage site at Manor Farm. I enlisted two other artists, Emily Orley and Elinor Brass, and they worked with the education programme manager for Hillingdon, Fabiola Knowles, in devising a wonderfully organic project called In Mercy For A Trespass. The plan was to build a durational outdoor installation with a selection of ceramic objects made by community groups and children and for these to be partly submerged around the moat and for it to collect rainwater over time. The installation would create the impression of an archaeological dig, now abandoned, overgrown and collecting water in a way that the moat no longer did. We worked with about 100 residents and school children and used their ceramic pots, cups and sculptures to create the installation. This should have been a fusion of contemporary and community art. However, what we did not foresee, was the relative conservatism of the area. Shortly after the installation was complete and before we had an opportunity to put down any signage or run a community event, we were informed that the installation had to be either substantially redesigned or removed. We were never able to have a direct conversation with the Councillor who thought the art work looked “messy” and "not very aesthetic.” The concept of it being allowed to grow into the landscape was lost on them. It was one of the most difficult projects to manage as Emily and Elinor quite rightly refused to rework the design without a more frank and informed discussion. Communication had broken down. Were we at fault as artists who had imposed ourselves onto the cultural landscape? Ironically enough, Emily and Elinor had prefigured this issue by calling the installation In Mercy For A Trespass. The heritage site at Manor Farm also used to be a manorial court and in the medieval era residents would have to pay fines for any crimes or misdemeanours and these would be couched in the terms of a trespass: "Richard Bacon puts himself in mercy for trespass in the grain with a heifer" or "Elena Thomson is in mercy because she gathered herbage from the standing grain of the lord contrary to the prohibition." After a cooling off period, another willow artist was brought in to tidy up the installation and make it look pretty. There is no denying this reworking of the design did look "aesthetically" better and more of a visual presence on the landscape. However the whole process, ethos and subtlety of the original vision was lost. The installation was renamed Ea Eard, which literally translates as ‘water earth’ in Anglo-Saxon language. This is the sweet-bitter project film made after the final installation was completed. Apart from one festival screening, this is the first time it has been given a public airing. There are some banana peels that are not protective.

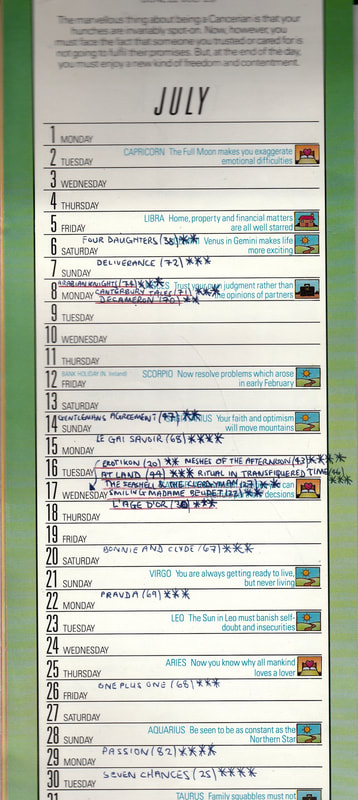

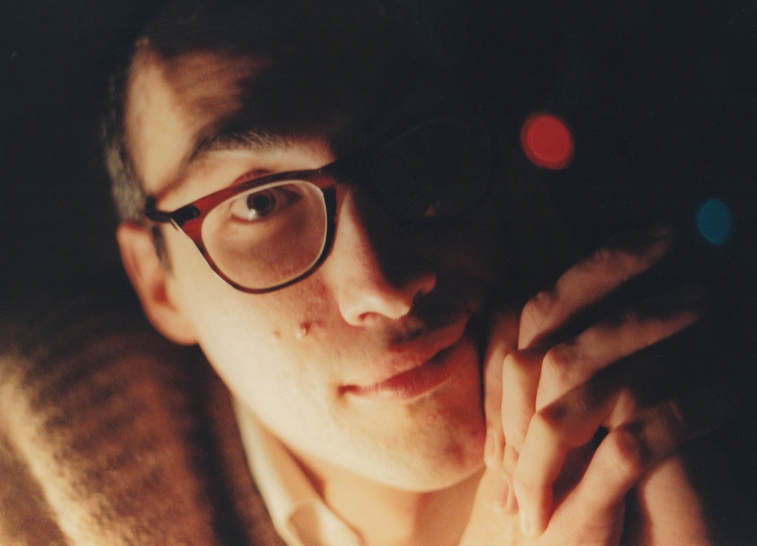

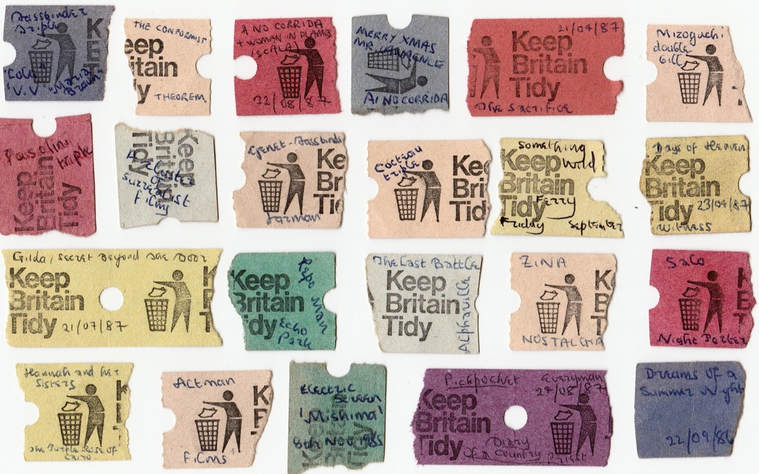

I recently treated myself to a double bill of The Angelic Conversation (1985) and Mirror (1975). I don't think any programmers have paired these two films before, but they resonate with each other, lyrically and visually, as well as offering divergent approaches to art based film making. Both were viewed on a computer screen, with the Jarman film rented online. However this screening of one film after the other was an act of homage to my golden age of cinema going as a teenager in the 1980s. After wee nippering at the ABC Edgware Road, I gravitated to the flea pit circuit that took in the posh Everyman at Hampstead and the grungy Scala at Kings Cross. During this period you could watch double or triple bill features in memorable combinations designed to shock and awe: The Exorcist riding on the back of Enter The Dragon; Terror followed by Savage Weekend (the rediscovered memory of Terror would inspire an arts project called The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle); Fassbinder double bills; and, not for the faint-hearted, a starter, main course and dessert of Pasolini films. Also, certain films that should not have been coupled, such as the groundbreaking In The Realm of the Senses (Ai no corrida). I’ve just looked over some calendars from the mid 1980s and was surprised to see how much film I was ingesting. There may have been a limited amount of TV channels in those pre-satellite days, but there was no shortage of films. Auntie Beeb and new kid on the block, Channel 4, had a public monopoly access to the film market. VHS was established and DVD was on the horizon. But to be able to see what your heart and soul desired, necessitated a trip to the picture house. It’s good to see there are plans afoot to design a Scala book, as the cinema produced lovely posters listing their monthly features. I usually hoard memorabilia, so I can’t account for the fact that I don’t have a single calendar month from my membership of the Scala. Perhaps it might surprise you to hear that I really can’t watch films anymore. I rarely go to the cinema. When you are in the business of producing art, there seems to be little time and perhaps inclination for seeking out art in your down time. Maybe it was also studying Film and Literature at the University of Warwick for 3 years and the celluloid feast we had as students, watching each film twice for close textual and semiotic analysis and which also included us projecting the 16mm prints sent up from the BFI. After ingestion, overdose?

While I had an eclectic taste, enjoying the classic narrative joys and happy endings of Hollywood cinema, it was the European art house movies that really tickled my fancy; although they did on occasion stretch your patience; the 317 minute cut of Bertolucci's 1900 seen at the Curzon Bloomsbury springs to mind. In the 1980’s, the work of two artists shaped my aesthetic outlook and personality: Derek Jarman’s gay-punk sensibility that pricked the constricting norms of Thatcherite society; and Andrei Tarkovsky’s metaphysical exploration of memory and haunting use of landscapes.

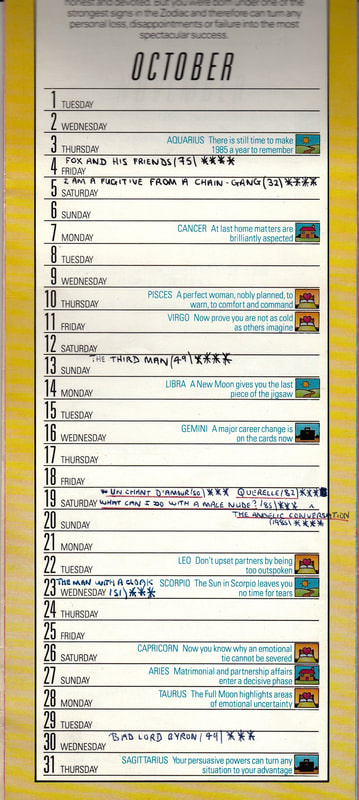

I had to write an essay to get into Warwick University (in addition to A level grades AAB and a medical examination!) That essay was on Derek Jarman’s The Angelic Conversation which I saw on both the cinema and TV in 1985. The film was a jittery and sensual evocation of Shakespeare’s Sonnets as read by Judi Dench. It was set in a timeless landscape of grainy, every changing palettes of muted colours that condemned men to drift and brood and lock horns in the slow-motion ritual of love and sex. The Sonnets themselves have an enigmatic quality that has divided scholars; the first 126 addressed to a man and the last 28 to the dark woman.

Abbey Fields, Kenilworth 1989

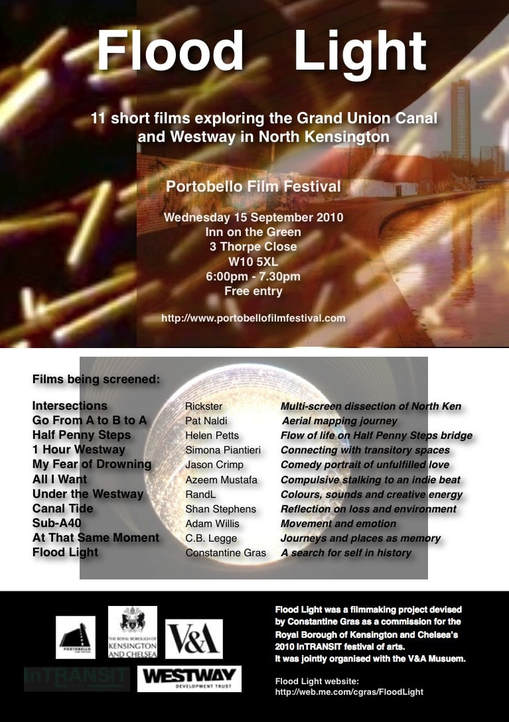

As a young man, dressed in my 1940’s suits, I seemed to wander in and out of both Jarman’s and Tarkovsky’s filmic landscape. I even had a dramatic film, This-That, inspired by my personae and made by fellow student and dear friend, Jacob Barua. That film was recently digitally remastered and there are plans for a sequel that updates the character into the 21st century. I better watch these spaces. After Warwick, I attempted to forge a part-time career as a stills photographer and eventually made it behind the film camera. Apart from several minor juvenilia works, my first real directorial effort was Flood light (2010). This was made for InTRANSIT festival of arts and I made a connection with the V&A Museum, later becoming one of their artists in residence. Although it wasn’t consciously conceived of as such, this film employed the strategies of what we might term the art film. The film used dialectical montage rhythms around the Grand Union Canal and the elevated road in the sky, Westway (A40). It fused together autobiographical elements (school books, carpentry tools), archive photos and film from the 60s and used period locations at the V&A to meditate backwards and forwards in time. There was no narrative drive or dialogue to guide the viewer in interpreting this stream of visual consciousness. A dripping soundtrack connected up images from beginning to end. It was a film about my urban identity in North Kensington. How I was able to intellectually and emotionally connect with water and concrete built environment. It is a film that has been aptly screened under elevated motorway roads in East and West London and in the Whitechapel Gallery. It has all the sins of a first film, but is probably my best work thus far.

Poster for Flood Light, 2010

In addition to making films, i have also curated film programmes and these have been useful platforms to support other emerging filmmakers. These are not exactly double or triple bills, but short films screened one after another and all inter-related on a specific theme. Flood Light was screened as part of a programme in which I invited other film makers to journey with me across the landscape of North Kensington. Local residents were also supplied with film cameras and edited their films at the V&A's Sackler Centre for Education. A panel from the V&A, Westway Development Trust, British Waterways and RBKC Arts selected the Best Film submitted for Flood Light and this was Intersections by Rickster. Henrietta Ross from British Waterways commented on this film: "I was very impressed by this. I thought the format worked really well conveying a great sense of movement. The sense of a journey was represented well, as was the great variety of activity going on around the location and the varied perspectives the location offers on West London life. I thought the different views were matched really effectively with a great eye for detail. The combination of colour, movement, stillness, nature and community activity was really engaging." It was also a pleasure to see an early film from film maker Azeem Mustafa who has since gone on to specialise in martial arts film. Simona Piantieri has also subsequently produced exceptional work. I particularly like the documentary film she made with Michele D'Acosta called A House Beautiful (2017). I followed up Flood Light with another curated programme called West Ten Fade Out (2013). This was able to showcase the film making talents of Dee Harding and Sandra Crisp. When I was the V&A Community Artist in residence based at Silchester Estate, I put together another selection of short films called Home Sweet Home (2014) around the issue of housing and domesticity. I particularly like sourcing archive films and using extracts that provide ironic or amusing contrast in the programme. I used two such extracts in Home Sweet Home and they are animated films from the Wellcome Collection. The Five (1970) is by Halas & Batchelor and opens with a young girl coming home from a party and going to bed; but her pooped toes take on a life of their own. The opening 7 minutes of Full Circle (1974) has exquisite art and animation by Charles Goetz that shows the development of city living and the possibility of over-population in the future leading to the collapse of civilised life. I have also tried to use film to connect residents with the history and social issues in the area in which they live. One example was a free screening I arranged of Leo The Last at the Gate Cinema in 2015. This was and is a profound film that connects with Lancaster West estate and Grenfell tower. I even wanted to screen this on Lancaster West estate for residents and the housing authority but circumstances conspired against that. The residents were locked in dispute with the Tenant Management Organisation over the Grenfell building works. I was commissioned by the TMO to make a short positive film of this regeneration taking into account the residents perspective. The film I delivered was a one hour long film completed in 2016 and called Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate. It was based on the life stories of seven residents. This was not a straight forward documentary with people speaking to camera. It is voice over set against the architecture of the estate. Although that film was deemed not fit for purpose by the TMO and fell into a state of limbo, I know that it really bonded me with residents in the community who have since become good friends. Hopefully it will have a proper screening in the near future. I have other footage that is strictly reserved for the police investigation. It isn't a good feeling to have art work that is delicately tied to the tragic events of Grenfell. There is no awe, just the shock.

2015 Poster for programme of short films, including rough cut of Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate

As I think of film, I draw and vice versa. I visualise films in my mind and these invariably start off as storyboard type drawings. The reality its that most films never get off the drawing board. But with the combination of drawing and writing, perhaps I can release some of that pressure cooker tension of being a multi media artist whose main aspiration is to make films. Let me conclude this blog by visualising a meeting of sorts between Derek Jarman and Andrei Tarkovsky on Hampstead Heath. Nothing is impossible in art and film. I need you to imagine that both are simultaneously drawn to the area for the making of a film.

Fade in.

A young man materialises out of the bushes, doing up his trouser belt, exhilarated, out of breath. A trickle of blood flows from his lips. Tarkovsky screams in Russian: cut, cut! The actor has wandered into the wrong film. A grounded helicopter rotor blade whips up a force of air onto the billowing grass and almost topples over the camera. Cut, cut. The production assistant rushes over to the helicopter. The timing is all wrong and aviation fuel is expensive. Tarkovsky curses under his breathe. Then looking at the bemused actor and the apologetic pilot, he starts to giggle and can’t stop giggling. The crew look at each other unsure whether to laugh. Tarkovsky motions for the actor to stand still and for the cinematographer to train the camera on him. Smiles all around and the actor looks up at the sky. It is a bright cloudless summer evening sky. A few rain drops start falling.

Cut to Jarman lining up his shot on the other edge of the heath, near a pond. He has torn up the script (that didn’t seem to be working) and is waiting for something to happen. His actors have got lost and a search party has been sent out. The rest of the crew have gone off for a tea break. A woman in her fifties dressed in a flowered dress walks into shot and sits on a log in the distance. She catches Jarman’s eye. He goes over and speaks to her. Hello, are you waiting for someone? She shakes her head in a combination of yes, no and don’t understand. He tries again. Would you like a cigarette? She nods and takes one. While lifting up the fag to his match, Jarman notices a raw burn mark on her wrist. Jarman wanders back to his camera. He zooms onto her. They hear the sound of a helicopter in the distance. She looks up in expectation. She appears to be acting. Jarman thinks she looks Eastern European, maybe Polish or Russian. He starts filming her as she turns her gaze to the pond and the gentle ripples on its surface formed by the wind.

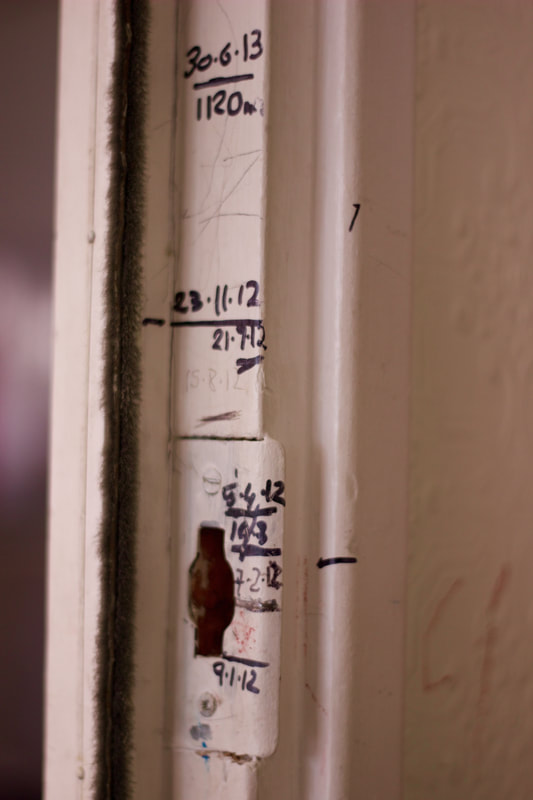

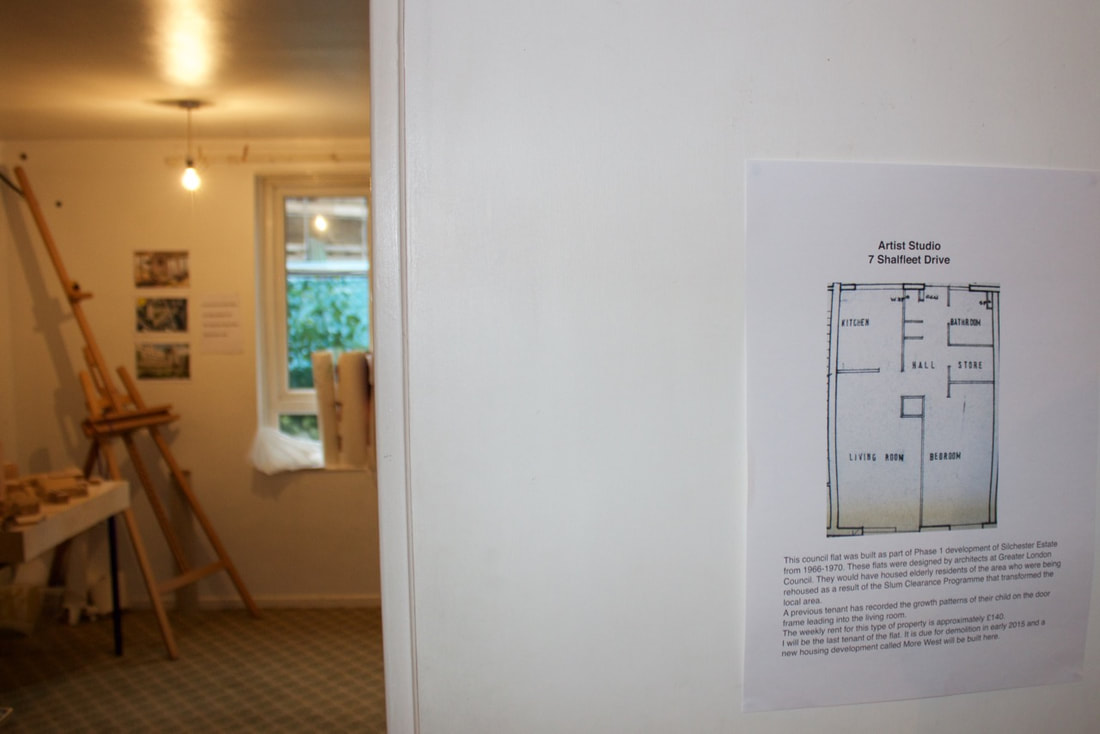

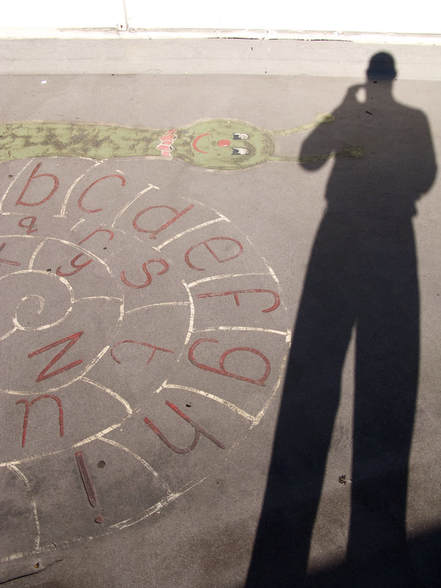

Fade out. Reflection from artist studio as More West is being built The chronicle of a child's growth recorded on a door frame Photos taken at 7 Shalfleet Drive, 2014 Can a building have a soul? If so, how might one measure this on a scale of soul from 1-10? One? Nah! This is just a plain pile of functional brickwork or unloved concrete. To give it a Presidential seal of approval, "a shit hole!" Five? Maybe given its provenance and state of use, there is a connection being forged between property and person(s). Perhaps a bog standard church and appreciative congregation might fit this bill. Ten? Now this might be hard to put into words. Some otherworldly sensory experience of an English castle made in heaven. A building that has survived carbuncular judgment and phases of regeneration. A cave you have carved with your own hands or flat packed assembled. Excuse these digressions, as this is completely uncharted territory for this author and a subject matter reserved for the confines of a philosophical department in a city of dreaming spires. Let us return to North Kensington terra firma. This blog is about 7 buildings, most within several hundred yards of each other: one was built as a film set and several have long since been demolished. They are St. Francis of Assisi church (c1860), 1-2 Whitchurch Road (1863), 2 Silchester Terrace (?-1960s), 7 Shalfleet Drive (late 1960s-2015), Latymer Nursery (late 1960s-2013), Grenfell Tower (1974) and More West (2016). The question I ask is do these buildings, historic or contemporary, have a recognisable soul beyond their outer facade? I have worked as an artist in three of them, one as a rented studio flat. While looking at spiritual qualities, I want to relate this to how I have used them in my art, the intersection of aesthetics and politics. To complicate matters, I have to declare from the outset that I'm not mystically inclined or believe in angels. However there is definitely more in heaven and hell than can be dreamt of in my atheistic philosophy. 1-2 Whitchurch Road House built for stain glass artist Nathaniel Westlake in 1863 Currently a St Mungo's house for homeless people St Francis of Assisi church Side chapel roof designed by John Francis Bentley, C1860's House for Nathaniel Westlake displayed at the V&A Museum, 2015 Acetate sheets, 3x3 metres Let us return back to that proposition. It is a line from a film, completely unscripted and conjured forth from the consciousness of the gardener at Lancaster West estate, Stewart Wallace. When I asked him how he knew this building had a soul, there was an even better quip: "I wouldn't be an angel otherwise.” The soulful building in question was 1-2 Whitchurch Road. Stewart had been living next to it for decades and said if he won the lottery, he would buy it and lord the manor. The building was the home of Nathaniel Westlake and designed by his close friend, the architect, John Francis Bentley of Westminster Cathedral fame. So we have soul pedigree here. During the 1860s they were both converts to Catholicism and working on St Francis of Assissi church which was a stones throw away from this house. This was a part of London noted for its piggeries (pig farmers) and potteries (brick works) and undergoing urbanisation with the coming of the railway and the growth of an Irish community. Westlake did not stay long in his dream house and we can perhaps speculate this is because the area developed into one of the worst slums in London. Amazingly this grand looking house, that is now listed, was once a squat and is still used to house homeless people. The building was a key location in my film, Vision of Paradise (2015). This was a meditation on housing and community using Dante's concept of heaven, hell and purgatory. In 1863 Westlake was working on his stain glass design, The Vision of Beatrice, to illustrate a scene from this story while living in the house on Whitchurch Road. This panel was collected by the V&A Museum. As an additional homage, I made an installation called House of Nathaniel Westlake, comprised of 30xA2 acetate sheets incorporating images of North Kensington buildings. Soul value: 8/10 for its origins and continued charitable use when this type of property would be snapped up by oligarchs and venture capitalists; although shame on them as they would not want to live cheek by jowl next to an estate! As mentioned, Bentley and Westlake put their heart and soul into St Francis of Assisi church. This is a small church with connected buildings on a tight plot of land, but the overall design and interiors sing of the unique talent of its guiding architect and artist. This is self-evidently a soulful building with a wonderful acoustic quality. For the remastered film soundtrack to This-That, I recorded two singers here performing a duet called Duo Seraphim. 9/10. Staff from the V&A Museum help me prepare for a community artist event 21/08/14 7 Shalfleet Drive, W10 6UF Mayor of RBKC meets local residents and architect of More West, Joanna Sutherland Demolition of Shalfleet Drive, 12/02/15 During 2015, I was the V&A Museum community artist in residence based at Silchester Estate. The first phase of regeneration was occurring in the area with the building of More West. I was embedded here with a studio flat at 7 Shalfleet Drive. This was part of a lower and upper deck housing block with 3 room flats that must have been designed for a pensioner or a couple, certainly not a family. So did this flat at the end of its social life have a soul? I would rate it 7 for its cosy uniformity of space, perfect for an artist who tried his best to give it back to the community with a series of bespoke art events that included film screenings and drawing/music happenings. Centre stage in the living room of that flat was a simple map which had photos of all the listed buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The addition of Silchester Estate on this map was the radical touch that only the locals noted. This map was a popular attraction to the visitors, including the then Mayor who came to an event called I Want To Live, Draw Me A House. Before she arrived, the police dropped by to inspect my premises. It seemed they had valued the spirit of the location in terms of a negative. It was an unknown precedent for Mayors to visit council flats on estates in North Kensington, even ones about to be regenerated. I was told this was a first. Film projection of Home about the last house demolished for the building of the Westway and Silchester Estate. It was screened at Latymer Project Space, formerly a nursery on Silchester Estate and soon to become More West. Photo by Emily Ballard, 2012. We move onto a house that now only survives as an archive photo. It was taken by the actress Mary Miller in December 1967. She wrote an accompanying letter that read: “I remember taking this picture of a house and a tree amongst the rubble and desolation of the early stages of the motorway from Bramley Road, looking west. It looked so forlorn and I admired the tenacity of the householder. i seem to recall it was an elderly man. There was something about him in the local paper of the time (I can’t recall which paper exactly). But a few weeks later he had succumbed to the pressure and the house was destroyed - also the tree. I think it all happened round about the time they blew up Maxilla Gardens for filming with Marcello Mastroianni.” This had all the ingredients to inspire the cinematic imagination. A small house that was left standing while those adjoining had been demolished. That solitary man with raincoat and hat standing outside. The corrugated sheeting. Even Mary’s reference to Leo The Last that was being filmed near by. I simply had to tell the story of this photograph. I presented this as a short film pitch to Latymer Projects. They accepted and I made Home for their inaugural exhibition. I acted the role of that homeowner from the photo. You don’t see me/him clearly as we move nervously around a house and twitch at net curtains waiting for the developers to serve us an eviction notice. At the end of the film, there is a panoramic shot of a net curtain house constructed on the Westway tennis courts, on a spot that marked the real life location of this lost house. Given all these resonances, I would have to evaluate this lost house in the photograph, as an 8 for its elegiac soul. Set design from film, Home (2012) Cinematography by Natalie Marr Film still from Leo The Last (1970) with Glenna Forster-Jones (left) Filmed in North Kensington and on Testerton Road before its redevelopment into Lancaster West Image kindly reproduced by Park Circus Limited Leo The Last is a quirky, enigmatic and powerful film that dramatically deals with race and social conflict. It was made by John Boorman in the late 1960s. It is a film of its time with hippie experimentation. Yet also profoundly prescient in that it tapped into the zeitgeist of the area. It remains a touchstone for thinking through art and redevelopment; it inspired me, as I feel certain it will continue to do so for other artists. The film makers were given unique access to the streets of North Kensington just prior to its slum clearance and they created a false house on Testerton Road. This had a white classic stucco facade and contrasted with the rest of the derelict houses which were painted black. This is a colour film with an impressive monochrome palette. Leo is the last in the aristocratic line and for the opening sections of the film peers out of his house with a telescope onto the world of his opressed black neighbours. He becomes radicalised by observing their plight, especially when he discovers he is their exploitative landlord. In true 60s fashion he decides to stage a revolution with destructive consequences. I felt a great affinity with Leo. As an artist, I was using my camera and drawings to reflect on changes to my social environment and in the process was being radicalised. I was getting a deep understanding on the cultural richness of life on these estates. Yes. There are social challenges, but these were not the sink estates as portrayed by politicians and councillors intent on running them down and forcing through regeneration schemes. As part of my community engagement, I got hold of a rare 35mm print as the film was not available in this country on DVD . I screened this for residents at the Gate Cinema (which is in the Notting Hill and not the Dale part of the borough). After watching the film residents from the estate joined me down at the V&A to create clay houses in response to the film. I was able to use this as part of an installation display at the museum. I have to give this film-set-building a 10 on the soulful scale. It has mythic and poetic qualities. It was built in order to be destroyed. Many local residents and the architects of Lancaster West Estate came to watch the impressive finale as the house explodes in flames. What did they think and feel watching film makers turn their former homes into a film set prior to its demolition for the building of Lancaster West and Grenfell tower? The soul of their buildings disappearing at a rate of 24 frames a second and then projected at cinemas in the following year to a largely unappreciative audience and box office. Latymer Nursery converted into Latymer Projects 154 Freston Road, 2012 (Bottom photo by Sandra Crisp) I also developed a strong connection with a former nursery on Freston Road that was built as part of Silchester Estate. This was handed over to Acava Studios and Latymer Projects as a temporary space for local artists prior to its redevelopment into More West. I made a film about the space and the 5 artists based here in its last days. I arranged for a local milk man to deliver one final crate. At 6am, in eerie darkness, I filmed him delivering his jinggling bottles. Then later on I improvised a sequence with other artists in which we walked around the nursery using these bottles as musical instruments and creating a trail of fragmentary glass. The nursery for children and artists had a special atmosphere. We were at home in its play spaces and rooms flooded by natural light. 8/10. More West was built on the site of my artists studio and the Nursery. It was an indicator of how the council wanted to replace social housing in the area by building around the high rise blocks. This must have also been part of the thinking behind the £10 million investment in Grenfell tower that was to follow. More West was Peabody housing for the 21st century: 112 flats with mixed social and market rent; £500,000 for a three bed flat and million pound penthouse pad on top, perhaps with a telescope trained down on its poor relations. Leo The Last meets J. G. Ballard’s High Rise. I tried to avoid my flat being used as a showroom by the developers and council. The architects model of the new housing block was on display next to a poster of the film Leo The Last. I would film spiders constructing their silky webs as builders climbed up and operated cranes. I got to know my immediate neighbours on the road who were waiting to move into More West. Some took this in a positive fashion, others clung to the memories of their former lives. The building was designed by Haworth Tomkins, complete with roof top sculpture that evokes Frestonia and has won many architectural awards. I have a soft spot for this building, but acknowledge it has yet to plant roots and be integrated with the high rise. 7/10. It is a building in need of love. Shalfleet Drive residents hand over keys to the developers, 18/01/15 More West (with crane in the centre) being built around Frinstead House on Silchester Estate View from the 17th floor of Grenfell Tower, 12/09/15 Building work collage: Frinstead, Markland, Dixon, Whitstable and Grenfell tower, 28/06/15 I wanted to conclude this blog by writing in detail about Grenfell Tower where I worked for one year four months. I was commissioned to made a film about the regenerated tower block and produce art for its new community room. I developed close friendships with residents. I don’t know how to evaluate the spirit of this building. It still pains me to talk about it in the past tense. As a postscript, let me branch out and offer a few comparative thoughts about the 1958 Notting Hill race riots and those tragic events at Grenfell Tower in 2017. Both shone a media spotlight on this area around Latimer Road station and exposed the deficiencies of society and council services. The chronic state of housing must have been a factor causing friction between white residents and the recently settled Afro-Caribbean community. Sociological studies took place into the root causes and how society could improve itself. In the immediate aftermath of both events, all manner of groups and social activists consolidated networks in the area to counter the lack of strategic guidance from the authorities. The Notting Hill carnival was one of the unexpected outcomes of the riot. What will follow the Grenfell Fire? I fear no positive outcomes in the short term. As of writing, the civil and criminal prosecutions are yet to unfold. There is great concern that the former will not address deeper underlying social issues and the latter will not result in anything other than corporate fines. It is a testing time to find spiritual qualities in housing and art. Burnt cladding in the garden of Lancaster West estate, 06/01/18