|

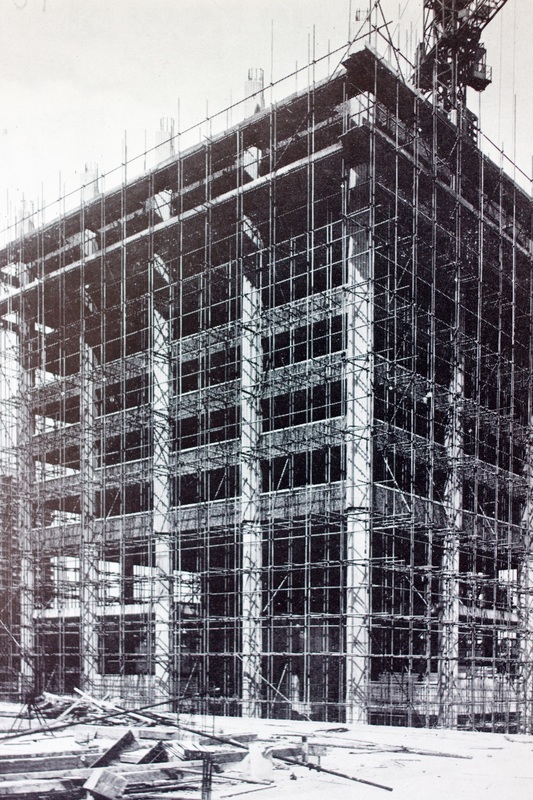

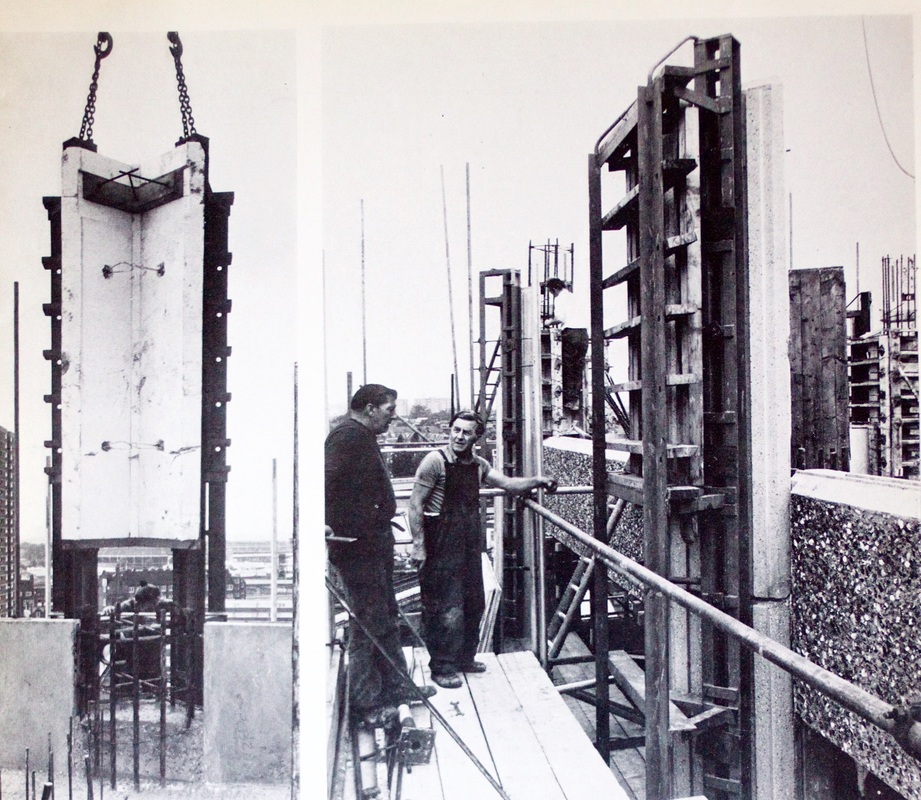

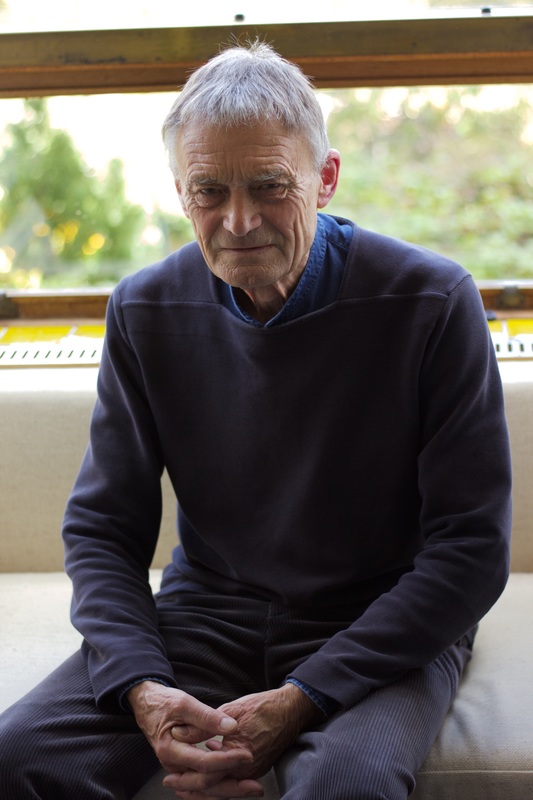

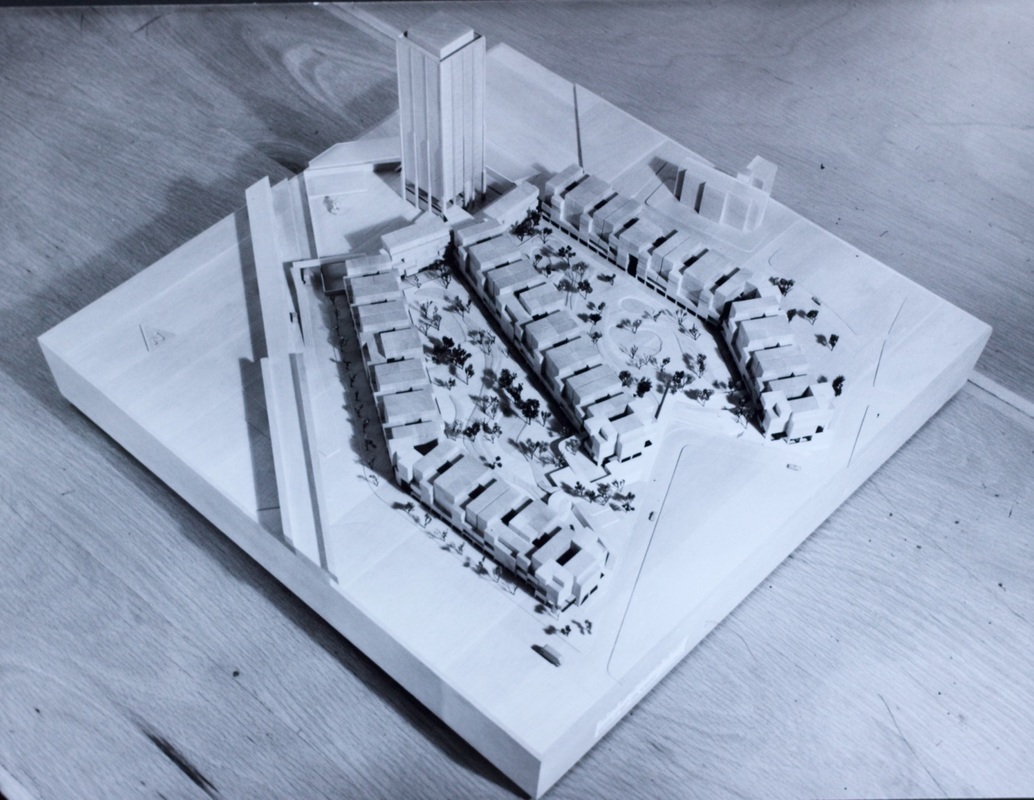

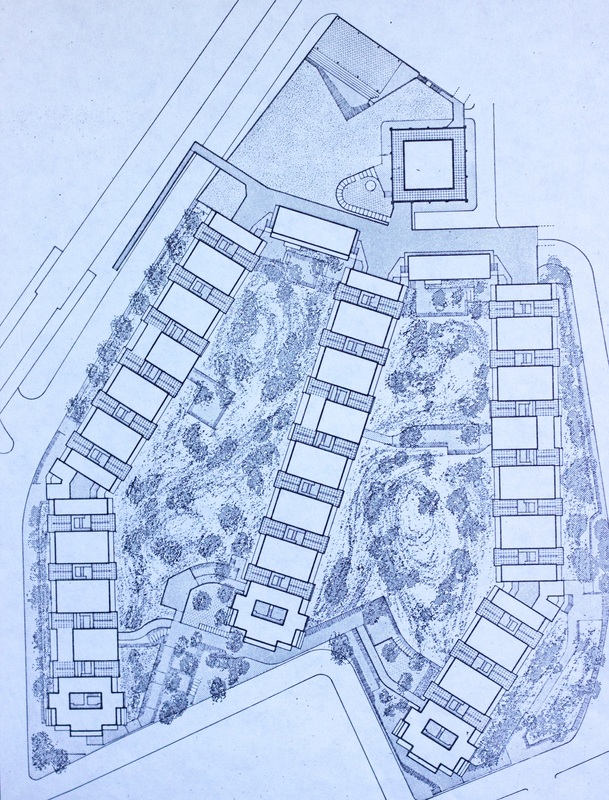

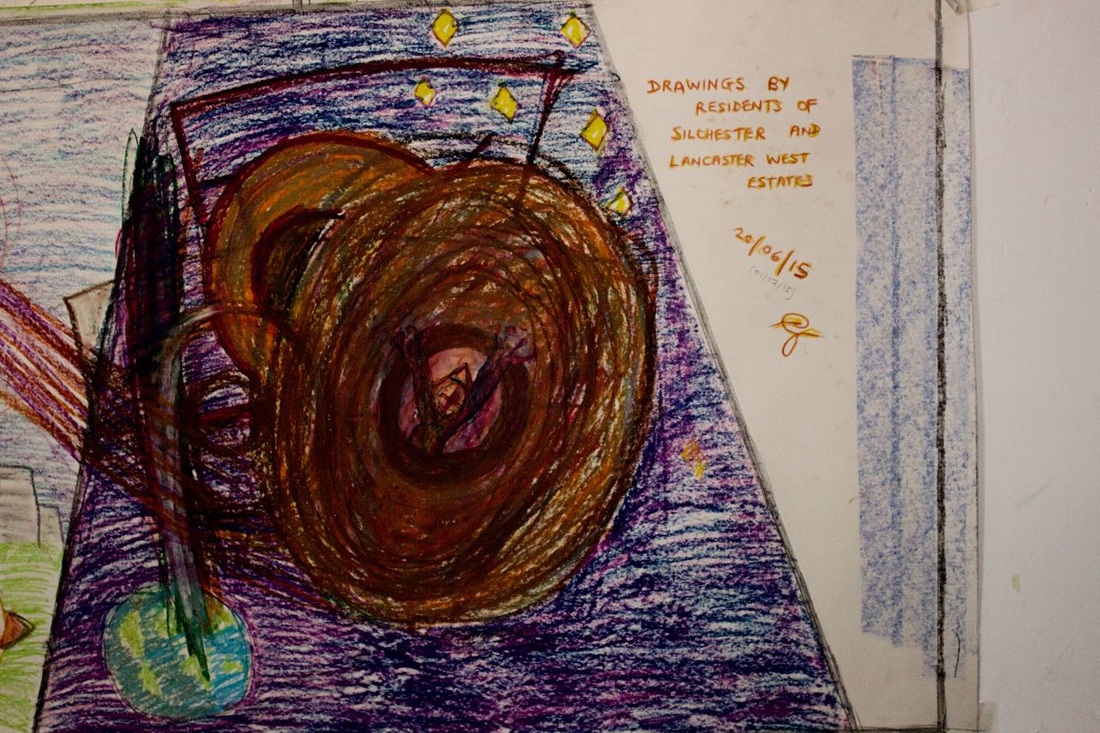

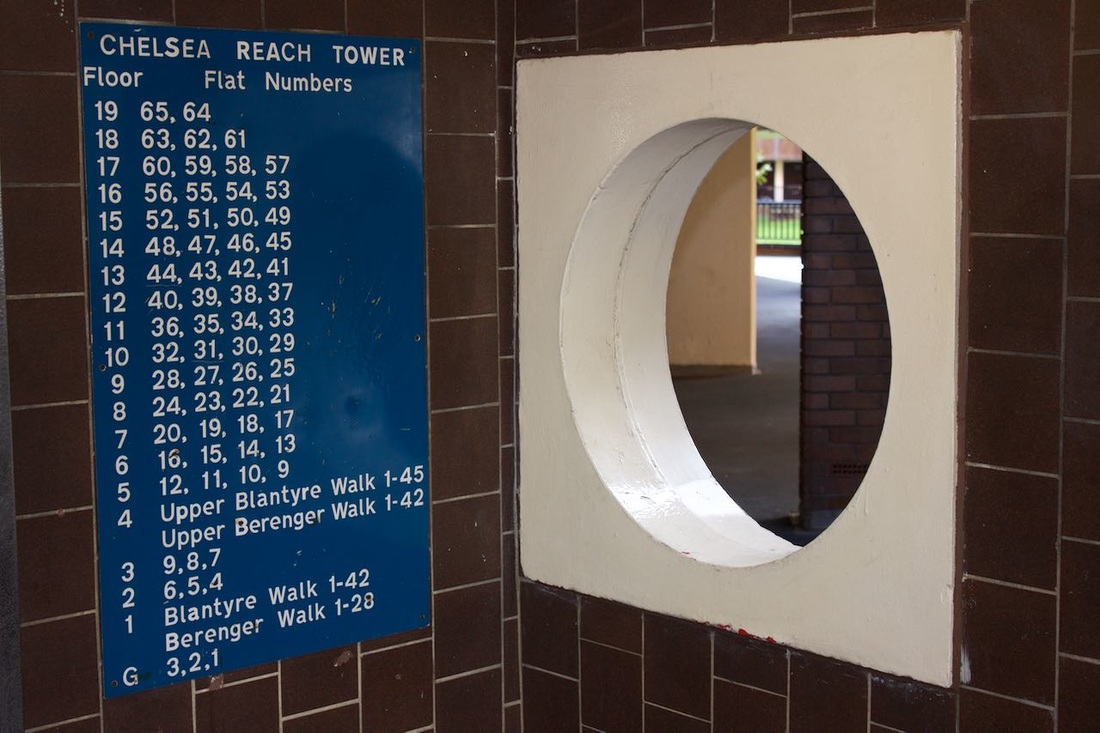

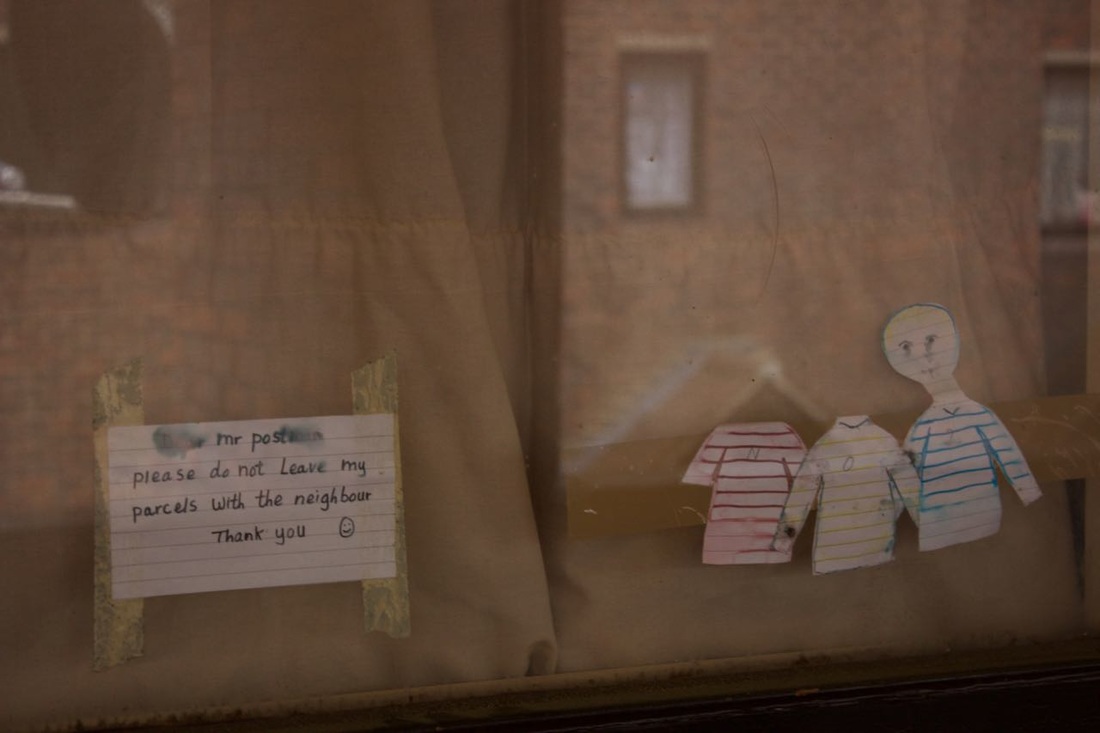

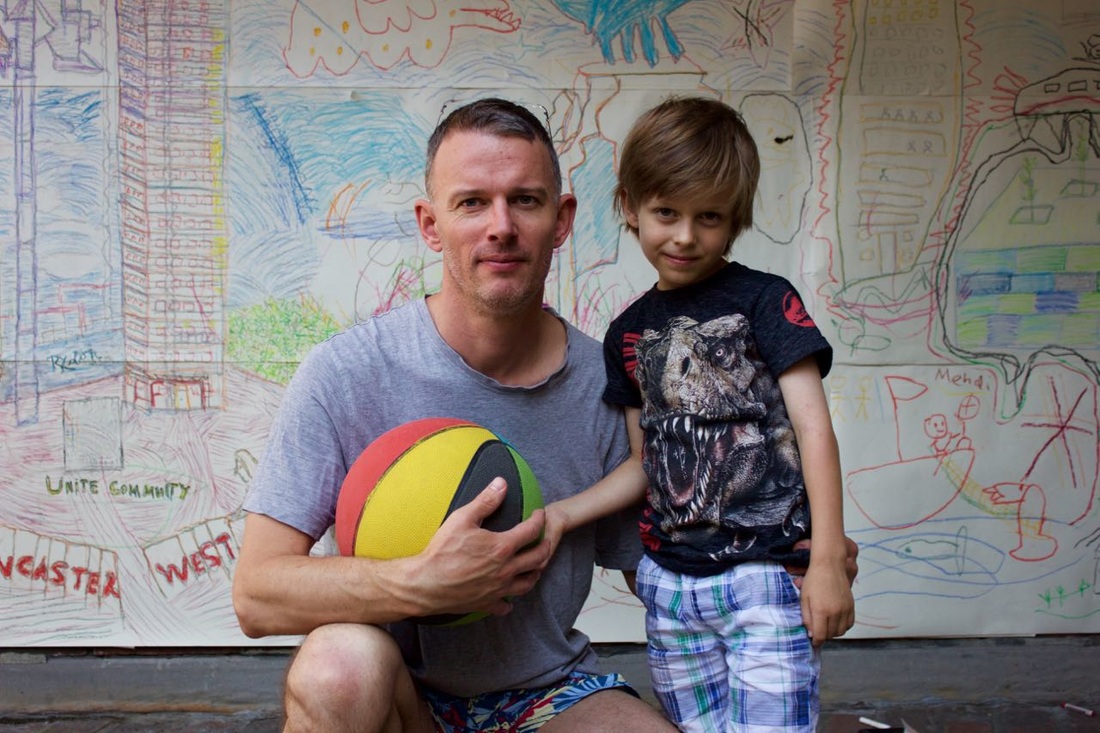

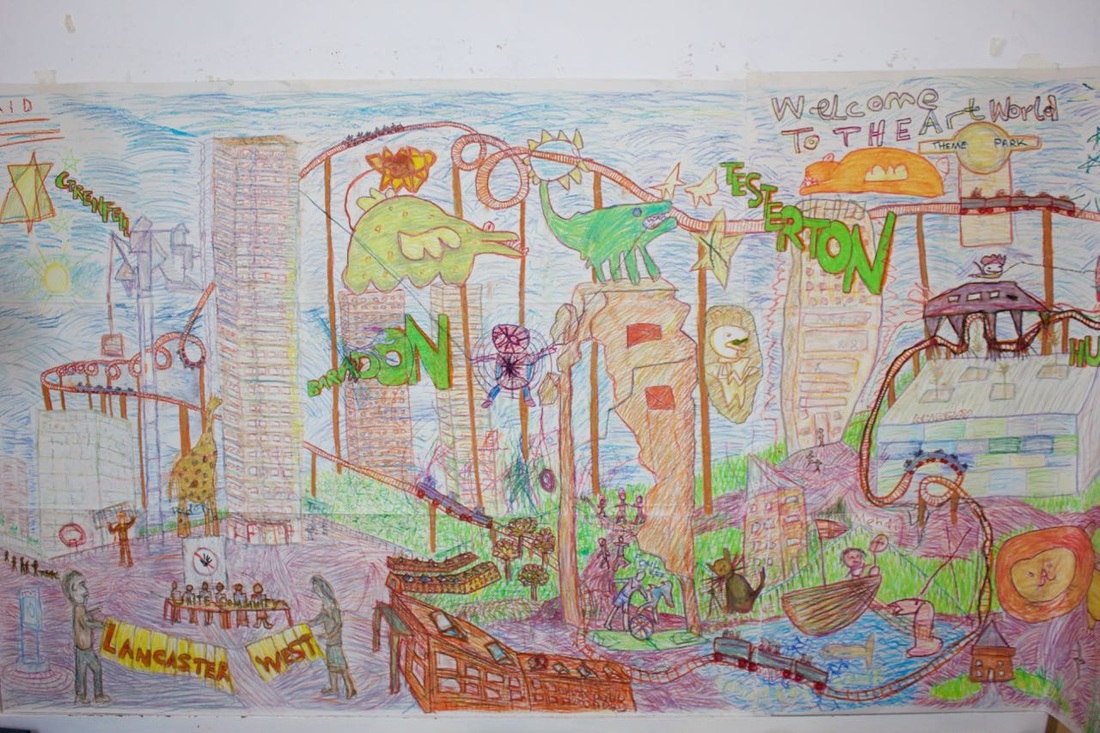

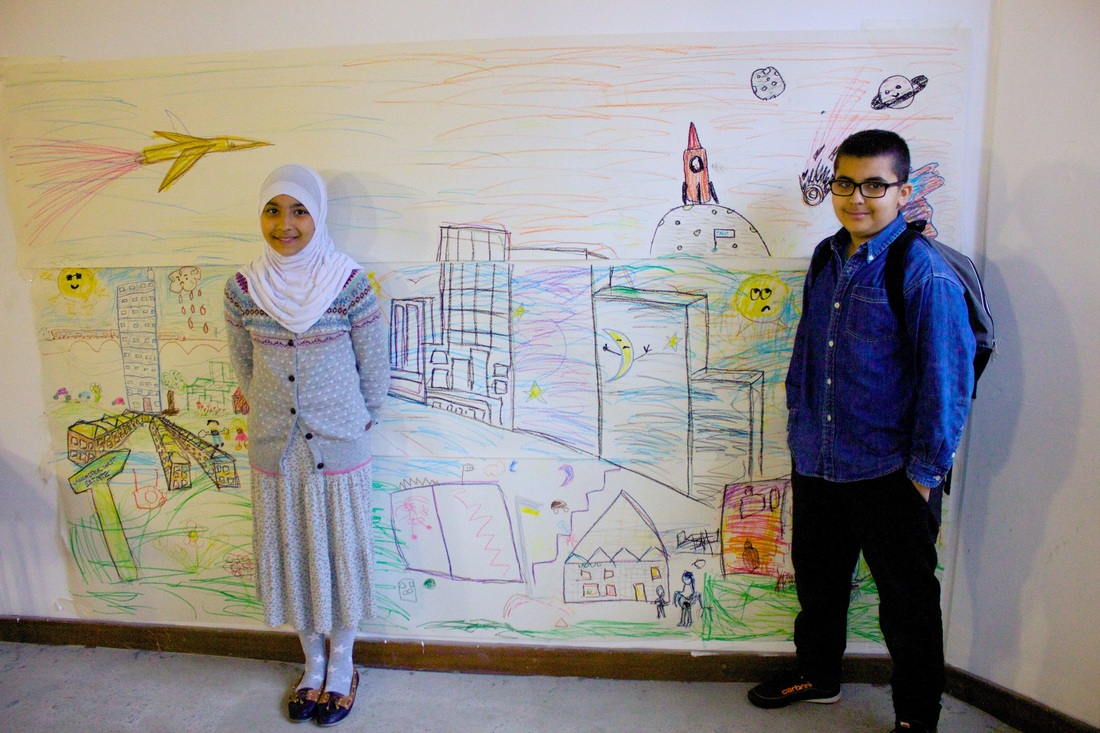

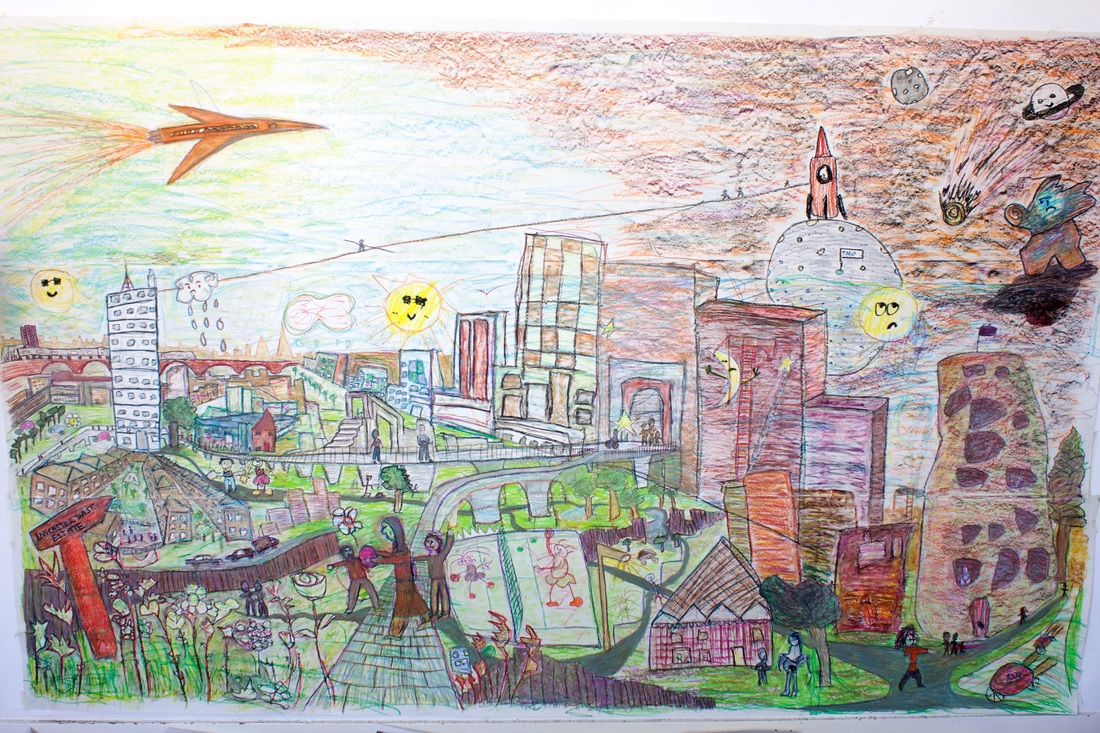

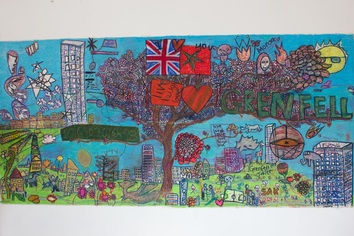

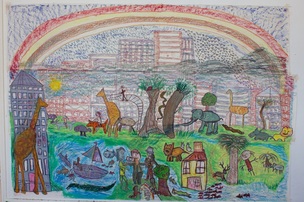

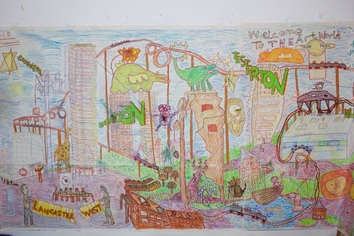

I've been working on Lancaster West estate for well over a year now. My commitment extended beyond the commission I had from the TMO (who manage the Royal Borough's housing stock) to make a mural for the new community room and a short film documenting the regeneration of Grenfell Tower. At the beginning, I was naturally regarded with a degree of skepticism. Why do we need an artist on the estate? But after attending numerous residents meetings and putting on art events in lift lobbies and during fun days, I earned my stripes in the community. During my tenure, I've had an opportunity to strike up many friendships across the estate. I offered them an accessible and sociable art. In return, several of them have entrusted me to render their remarkable life-affirming experiences and energising humour. More of these residents to follow. But first let's talk about regeneration and architecture and conclude by weaving both of these back into the beating heart and soul of Lancaster West. As of writing, Grenfell Tower improvement works is well nigh complete. After a £10 million regeneration, nine new flats have been created and offer affordable rents in an area where property prices average over £1 million and one bedroom flats on nearby More West are over £500,000. Each flat in Grenfell has had double glazing installed and a boiler for direct control of heating and hot water. The building has been thermally insulated with a new layer of cladding, although I miss the former design. The nursery and Dale boxing club also come back into vastly improved spaces and facilities. This upgrade to the fabric of a building is important in the context of how the council plan to regenerate this part of North Kensington. Silchester Estate, which is just across the road from Lancaster West, is currently being considered for regeneration. The initial options produced by the council were described as "nuclear" by estate residents. At a recent meeting in the town hall, several residents had the opportunity of making powerful statements to the council about the lack of consultation and the potential impacts of wholesale regeneration on the community and environment. The council listened and voted to explore the options in more detail. They also make a commitment to factor in the possibility of maintenance and infill. It is good to see how local residents are campaigning with a witty strap line (Gradual Change - In Due Course) that might have been culled from the insight of a former architect of Lancaster West, Derek Latham. He developed his ethos of urban renewal on a gradual basis after witnessing the impact of "slum clearance" in North Kensington during the 1960s and 70s. Previous blogs have featured interviews with Derek Latham and Peter Deakins, both of whom worked on the early stage design of Lancaster West estate. I can now present a complete documentary record of all the architects involved and their experiences, hopes and frustrations. One major issue was why the estate was never designed to its initial masterplan. This sense of fragmentation is perhaps the root cause for many of the challenges still being faced on the estate and which are being addressed by the newly formed Lancaster West Resident Association and the Grenfell Compact. I recently had the pleasure of meeting retired architect Nigel Whitbread and showed him around the estate. He lead the team who designed and built Grenfell Tower. It was the first time in over 40 years that he stepped foot inside the tower and enjoyed visiting a residents flat and those stunning views. What's interesting about Nigel's story is that he is a local boy through and through and not many local people seem to be aware of his role in the development of the area. We are also going to hear from Ken Price about the design of the finger blocks, the three low rise housing units that radiate out from Grenfell tower. Clifford Wearden is the design godfather of Lancaster West estate. I suspect his career path was adversely affected by the way the development panned out and not being the consultant responsible for all the later, much revised, stages. Chatting to his widow, Pauline Wearden, I was surprised to learn that, Clifford, like most other architects involved in the project disliked tower blocks. Grenfell tower was only included to maximise housing density levels; Nigel is an exception to this prickly high rise rule of thumb. This perhaps explains why Clifford in later life would drive over the elevated Westway and look across at the five tower blocks and declaim to his family that Grenfell tower exists no more and has been demolished for a new development. This is a poignant case of not wanting to see the concrete from the stone! Nigel Whitbread: I was born in Kenton near Harrow. My parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington. We moved as a family to this area in 1949 to be nearer the shop. I read quite recently Alan Johnson’s biography, This Boy. He is a Labour MP and former Home Secretary and interestingly was born in 1949. However his life and the poverty he lived through was in a different world, although just a mile away as the crow flies. He didn’t enjoy the family life that I enjoyed nor did he appear to enjoy his time at Sloane grammar school which I had done earlier. When I was going to leave Sloane, I didn’t know what I was going to do. One day I had an interview at an architect’s office. My eyes were opened. I liked the idea of drawing boards and doing something that I never understood to exist. The first firm that I worked for was Clifford Tee and Gale and that’s where I did my apprenticeship. I went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this I became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. I knew through delivering groceries that there was an architect who lived near my father’s shop. I told my parents this and my mother said she would speak to the wife of the architect who was also a partner in the practice. I went for an interview and got the job. This was at Douglas Stephen and Partners and this was probably the most influential time in my career. It was only a small practice but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that I worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. It was actually like going to a club and we were doing terrific work. Later on, I went to work with Clifford Wearden on Lancaster West. At that time his office was a two storey building in his back garden. It was a huge job for a small group. It was unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. Clifford was a serious architect but had a flair about him. He’d been in the Fleet Air Arm and had a lovely Alvis car which was a convertible as I recall. He did have a very bad habit whilst he was driving of turning his head and facing me whenever he was speaking which I always felt a bit disarming. I found this quirkiness an attractive aspect in somebody who was very precise in most things he did. The whole scheme had been well prepared and thought out by the time I joined to lead the team in designing the tower. The design is a very simple and straightforward concept. You have a central core containing the lift, staircase and the vertical risers for the services and then you have external perimeter columns. The services are connected to the central boiler and pump which powered the whole development and this is located in the basement of the tower block. This basement is about 4 meters deep and in addition has 2 meters of concrete at its base. This foundation holds up the tower block and in situ concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams all tie the building together. Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968, had been built like a pack of cards. Grenfell tower was a totally different form of construction and from what I can see could last another 100 years. Grenfell tower is a flexible building although designed for flats. You could take away all those internal partitions and open it up if that’s what you wanted to do in the future, This was unusual in terms of residential tower blocks. I also don’t know of any other council built tower block in London or anywhere else in England that also has the central core and six flats per floor rather than four flats which is typically done on the London County Council or Greater London Council plans. We were wanting to put our own identity on this. The GLC built Silchester estate and I had nothing against that but this was so different in many ways. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, we thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. We used insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, lifted up and put into place with cranes and they were so much more quicker. In an architects mind, they want towers to be an elegant form rather than stumpy. This was a challenge and was why I introduced as many vertical elements within the fenestration as I could. The only thing I could play with was the windows and the infill between the windows. I treated it like a curtain wall, to get the rhythm of a curtain wall. We lost some of this verticality in the recent re-cladding but it’s not the end of the world. And the building is now better insulated as we had different standards then. The floor plans were based on Parker Morris Standards which they used at that time and sadly have gone now. These were very good standards for storage and the way furniture had to be included in the plans. It was delightful to hear that residents thought flat arrangements worked well and I saw the views recently which I always thought were terrific. I wouldn’t have minded living in a tower block myself. Tower blocks were criticized for not being suited to people or a lot of families were being forced into it and they were feeling more and more remote from the street and meeting other people. But there is another side to this and it always seemed to me that if American’s can live in tower blocks, why can’t the English? This is the first and only tower block I designed. This was also the first social housing I ever worked on. No social housing has been built since this and I’m very much against knocking things down unnecessarily. I had heard that there had been problems a few years ago with the heating and it was no good and talk of the whole block having to come down. And I thought, if my heating goes wrong, I don’t want to pull my house down. It’s a great shame that the basic concept for the whole of Lancaster West to have a first floor deck for people, shops and offices and parking underneath wasn’t seen through for whatever reason. This means that there remains a basic flaw. Clifford Wearden and Associates only built Stage 1 and the remaining parts were built by other architects. I don’t think the designers are to blame because there was a requirement that it was designed to have cars for every flat. We’ve all seen things have changed dramatically since then and now cars can’t be accommodated everywhere. After Clifford Wearden, I worked for Aukett Associates and I was there for 30 years until retirement. Recently I’ve become involved with my local residents association and committees in drawing up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan. We included the Imperial West site over in Hammersmith and Fulham because that was already impacting on our conservation area. Hammersmith wouldn’t agree to this but we continued developing the plans liasing with RBKC and residents. The Neighbourhood Plan includes objectives around shopping, housing, offices and conservation. We have also identified 3 existing unbuilt spaces which are now designated as local green space and cannot be built on. Latimer Road is included in the plan and we think that could be redeveloped to improve the area and have more housing put on top of the business units. We have to have housing somewhere. That’s where you could do it. But don’t build on our green spaces. The Localism Act which the Conservative government introduced is a very powerful tool actually. Residents are able to influence the way their area is developed. Ken Price was lead architect responsible for the team who designed and built the finger block units (Testerton, Barandon and Hurstway) which formed stage 1 of the building project. Ken Price: My origins are in Derby in the Midlands. I went to the School of Architecture in Nottingham which at that that time was part of the college of art and is now part of the university. I worked for a short time in Derby and then I was offered a job to work in North Africa in Tunisia. I went there for 3-4 years. I came back and worked in Nottingham for a while with some ex-students who had set up practice there and and then changed jobs in and around London. After Lancaster West, I worked with Casson Conder partnership and was job architect on the Ismaili Centre in South Kensington. Subsequently I set up my on my own and did small scale projects, mostly interior work and retired a few years ago. Clifford Wearden won the Lancaster Road West development in Kensington. After a bit of a hiatus, the commission was confirmed for what was called stage one and he asked me to go and lead the team as project architect for the finger blocks. I worked for him and Kensington and Chelsea to develop the original masterplan which predecessors had worked on. Clifford was extremely good at handing over and saying - look this is the problem, you solve it and refer to me if there is still a problem. He was very generous although he had the overall view and concept. I know that he was very sad that the development became a little bit like the Barbican. It was a grander scheme and there could well have been more productive elements which just didn’t arise. I wasn't involved in those preliminary stages of development, so I can’t speak too much about how that evolved. But I was aware that the Silchester Baths on the site became listed and affected the masterplan. I briefly saw the housing in the area before or after it was all painted white because there was the famous or infamous film, Leo the Last. Was it black or white? Why did I think it was painted white. The director was John Boorman. I think I must have seen it just before they did that and probably immediately after. After it was cleared there was no real evidence of life or to how it was. I don’t even know what the state of the dwellings were like and whether they were totally without facilities. At that time there were a number of schemes underway to deal with the housing issue, alongside the problem of car ownership .One could describe it as the deck system when cars were kept down below and freeing up the ground level or the raised ground level for pedestrian use and housing. It was part of the brief to provide that amount of parking and it did subsidise some of the other elements. My predecessor had sketched in a basic outline of the finger blocks. I took that on and developed up the detail of the individual housing units and the spaces between. I suppose we were interested in the intricacies of locking together volumes of accommodation in order to maximise the space of each dwelling. Also providing, to a degree, some private outside balcony or roof terrace on the top areas so there was an opportunity for people to have their own little bit of outside space as well as the bigger outside. I still have a small model of the finger block that was made by a friend of mine, a model maker. It shows the different accommodation elements by colouring. It was really a demonstration to the council on the mix of the different elements. Community garden between Barandon and Testerton Walk. A constant source of artistic inspiration for Constantine Gras and featuring as the backdrop for several of his films: Vision of Paradise. The landscaping was dealt with by Michael Brown (landscape architect, 1923-1996). Clifford was very determined to ensure that the landscape was taken on and he persuaded RBKC to employ him. I think one of the essential elements in the concept was this endeavour to provide as much open green space as possible by concentrating the housing units. The density was probably what was expected or required by local authorities at that time. The estate was designed to try and retain that as much as possible and the tower blocks were an element in that because you’ve got a concentrated stacking of accommodation which again added to the freeing up of groundscape. Although there were a number of tower blocks around at Silchester I don’t think any of us would have chosen to have incorporated the tower block but it must have contributed to this density issue and freed up the amount of green space that was enabled. I think the estate was built to a good standard. We persuaded a brick manufacturer called Ockley to make bricks especially for the estate which weren’t available. It was just at the start of the introduction of metrication and it seemed to me, in particular, that it would be rather nice to make life easier in measurement terms to have bricks that fitted the metric. So they are specially made, 30 centimetre long bricks. We wanted to use brick as the main element in order to connect perhaps with the past more than you would have done with clip on panels. It does survive time rather better than a lot of materials. I still imagine they look pretty good. They were very nice brick manufacturers. I knew there was a hiccup in the construction process but I couldn’t quite remember what it was. (The contractor, A.E.Symns went into receivership in 1975 at the very end of the construction of phase one). I can’t think of a building site where that didn’t arise especially as the construction was over such a long period. There were industrial dispute problems (three day working week and building strike), but not hugely disruptive as far as I can remember. In those days it was very difficult to get contractors to keep the site clean. Now because of health and safety issues, I think building sites are much better managed. It’s a shame they never built the planned shopping centre or offices. There was an expectation of community facilities including commerce and everything else in order to make the place work. I don’t think there were any warnings flagged up that there might be vandalism. It certainly wasn’t in evidence as it was completed. I visited after it was fully occupied and there didn’t seem to be any evidence of vandalism then. We never got any feedback as a practice on you should’t have done this or that. Perhaps we could have foreseen some of the possible problems. At the time disability access wasn’t an issue. It should have been but it wasn’t. Now that wouldn’t be allowed. You have to provide much more facilities. Unless the facilities are provided people will abuse what’s there and definitely need alternatives. Maintenance has been the problem in almost every area of social housing that was built at that time and subsequently. it’s one thing to realise and provide housing for umpteen people, but then to not maintain the estates or keep them going. It was very short sighted. That’s why social authority housing has all but disappeared because nobody is prepared to take on the long term issues. It was a product of its time in the way it dealt with a big housing issue, sub-standard housing. And hoping to provide the mix of urban renewal, accommodation, green spaces for enjoyment, kids playing and all the rest. This was just one of a number of schemes which were resolved in different ways but the deck idea was a sort of constant thing throughout. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Estate, which is due for demolition now, was one of the background influences on the concept of Lancaster West. There was also a reference perhaps to the Lillington Gardens estate just off Vauxhall Bridge Road. That’s a famous development by Darbourne and Darke which I think still survives very well. Ideas of large scale redevelopment and housing tend to go through different phases of acceptability or relevance and it’s very difficult to look back and say that was the right decision to make. In some cases it was the only option either because of financing or government pressure or politics. But I would have thought that if the masterplan was completed it would have provided a better result than has eventually arisen. But it’s very difficult in hindsight ever to say. Pauline Wearden whose husband was the lead architect for Lancaster West estate masterplan and building stage 1. Pauline Wearden: Clifford was born in Preston, Lancashire in 1920 to working class parents. His father was a plumber and his mother was in retail with a profitable cafe. Clifford was his mother’s golden boy and she paid for him to go to university. There were no architects in the family. It just came thorough Clifford. Clifford studied architecture at the University of Liverpool from 1938-40 and 1946-48. He was very fortunate because that was a prestigious university in those days turning out many famous architects and Rhode Scholars. When war broke out, he immediately volunteered. He had a lovely war, mostly cocktail parties. No. No, He did have a lot of tragedy and he saw his best friend shot down. Clifford was a pilot in Air Command. He had travelled as a student on what they call the Tour and he’d been to all the classic places but during the war he also saw some exotic places. From 1949-54, Clifford was chief-partner for Sir Basil Spence. This was when they got the commission for rebuilding Coventry Cathedral and Clifford was given the job of preserving the ruins. He was very proud of that. I don’t know what brought him to London. But he had no home and went to International House Hostel. He lived in a hostel for years. He didn’t have anywhere stable until he bought his top-floor flat in Argyll Road, Kensington. Then he came across this derelict house on Homer Street, Marylebone. They were a row of 6 Georgian houses in that street and the property owner wanted him to do up the other houses as well. So he worked on those and then bought one of them. That was probably one of of his first jobs alone. By the time I came on the scene in 1965, Peter Deakin was there and Derek Latham was a student. Clifford built an office at the back of the house. A very nice studio designed by him which was contemporary which might have looked strange at the back of a Georgian house. This is where the master plan for Lancaster West was prepared. Eventually the practice had to relocate premises as there were twelve in number. It was like I married twelve men because they were always in our house. Clifford came home one day and he said they are blowing up one of the houses in North Kensington. And we said - what! And he took us all in the car at night. The director was just about to film the house being set on fire and demolished. They had all the safety people and security and police vans. We had to creep through the security set up. Nobody had invited us but we said we wanted to see it. They had built a false house to make a cul de sac and when you looked it was completely false, but it didn’t look it. So we were exactly there for the big bang. The children were thrilled. I can remember seeing big cameras, arc lights, just like you dream for an outdoor film set in the dark. It was typical of Clifford to have the children up. He didn’t want them to miss anything. However, I don’t think Clifford ever saw the finished film, Leo the Last. He wasn’t particularly interested in films. Lancaster West was his first very big job. But he got into the mould very easily. He more or less expected it working with Sir Basil Spence and being up there with all the old Liverpool people. He was very much an architect’s architect and he felt that his time was coming. Some architects don’t like meeting their public, but he was very good at that. I think he listened to them. One of his ethos things at university was social housing. So he felt very strongly about it. Of course, affordable housing it’s called now. I think he’d be absolutely disgraced by some of the policies such as right to buy. However, I don’t think he was a socialist. I don’t even know his politics but he was fairly traditional in many ways. We married in 1969 and you took over your husband’s life or it took over you. He was doing very well in 1969 but of course it’s a hand to mouth existence. Your only as good as your next job and the 70s were quite stressful and then in the 80’s the work fell away. We had to economise and got rid of a car. We were trying to think of other ways to save money. It’s very difficult when you’ve been having a certain lifestyle and it worried him terribly. He used to worry about what might happen and I always felt that was a terrific waste of time. He lost quite a lot of sleep over some jobs. Clifford believed that the tower block at Lancaster West was demolished. We drove past it on the Westway. He said it’s no more. And I remember saying to him, that we should have gone to see it come down. In the family we all thought it had gone but one day my son said it was still there. I think he would have been relieved, quite honestly, if it came down. He didn’t want it built. He didn’t want to be in this era of tower blocks. He felt very strongly about vertical living. It wasn’t right. So I don’t think he took any pride in it, except that it was not a bad building and it did work. I’ve never really appreciated that Lancaster West was landscaped or intended to be. In the model of the estate that my son has hanging from the wall in his house, there are little trees made by Ken Price. And they always put trees in as their panacea for making it look homely. But it did look good in the end and not as desolate as it might have been. I’m afraid to say that driving past on the Westway is the nearest I’ve ever got to seeing the estate. I’ll have to go. The best way is to walk around, I imagine. I'm going to end this essay with a few extracts from residents who live on Lancaster West estate. We are not now talking about perspectives and plans or so many housing units that can be redeveloped. We are talking about homes. People who have planted roots, raised their family and want to retire with peace and dignity. These flats and houses that were designed and built in the 1960s and 70s are now home to a diverse range of people who want to live in one of the richest boroughs in the universe. They deserve to have the final word. One hopes that in 10 or 20 or 40 years time, that they are still living in the area, as the new kids on the block are contemplating how to buy into the next cycle of housing redevelopment. Christine Richer, resident of Hurstway Walk: My mother was an African-Welsh woman and my father was black African American. They met after the war in the West End. Two weeks after my 18th birthday, I came to London and I landed in St Stephen’s Gardens in North Kensington. Massive, one room bedsit with the kitchen in the corner and the mice. The mice were hell. That was my first living in a big city. I came to the estate in the 70’s. Funny story. The first day I came here to meet the electrician and the gas people. No one turned up. I end up sleeping on the floor. And I had the most vivid dream of my life. I wake up in this dream watching my coffin being carried down the stairs. I saw these two shapes and they were my daughters. But it was very pleasant. I thought this is my place. My place on earth. I’ll live here till I die. As a child, I moved a lot. In Grenfell Tower there was a really nice club, like a residents social club and my partner at the time was on the Committee. That was my first introduction to the estate. It was full of different people who knew each other from the neighbourhood: Moroccans, Africans, blacks, whites, Portuguese, Spanish. I think with my involvement in the resident association and Estate Management Board, when the children were young, they have learnt a sense of community. They would always come and help me if I say I’m doing something with the R.A. Volunteer themselves, wash dishes. The garden down there was very important to me and the kids. They spent their formative years down there with or without me. We had family parties, barbecues. That living space outside there meant a lot to me. I do believe that we are going to get knocked down as all this gentrification is happening all around us. And we are not a Victorian block which is a beautiful thing. We are a 1970s fling them up, fling them down block. I don’t know where I’ll end up. That’s the biggest concern for me. That makes me stay awake at night. That makes me cry. If they could build another block, 4 or 5 streets away, where I knew I was going to be rehoused. It could be Manchester. All my close friends who live on the estate, only about 3 are here. Everyone’s gone. It’s a changed community. I haven’t always loved all the neighbours. But the neighbours that I have liked and I’ve made friends with, we’ve loved living here. The old families who brought up their kids and their kids have grown up and moved away. It’s been a home to a lot of people. Edward Daffarn, resident of Grenfell Tower: I’ve lived in Grenfell Tower for over 15 years now but I’ve lived in North Kensington, Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill Gate, my whole life. I found education was quite a therapy. I became a social worker for about 7 years. And then sadly my mum, got motor neuron. so I gave up work to look after her. I haven’t got back into social work. But what I have got involved with is housing issues on Lancaster West and in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The stuff that we’ve been doing on Lancaster West started as a result of the Academy being imposed which was 5-6 years ago. When we first started there was virtually no community groups around. Five years later there's a lot of community activism because of what’s been happening in housing. Westway 23, Focus E15 Mothers, The Guinness Trust down in Brixton, Our West Hendon, Sweets Way and all the radical housing network. There’s all these different struggles. On the 24th June, this year, 2015, the council passed a motion in the full council meeting saying that they were going to go ahead with the destruction of all low density social housing in North Kensington. Low density means this, They’ve been built nicely, giving people some space inside and with some green residential amenity outside. Trees and green space for their children to play in. Low density housing. It’s not anything else. It’s just nice estates. It will be interesting to see what will happen to Silchester. Because sooner or later, one community is going to say, and it only needs one or two inside that community to lead the rest - just to say - your going to knock our houses down - oh yeah! Oh yeah! Let’s see about that. North Kensington has a good history of not just taking these things lying down and when people finally wake up and realise what is going on, maybe the council will get a bit of a shock. They call Lancaster West the forgotten estate. And it hasn’t been called the forgotten estate for the last couple of years. It’s been called the forgotten estate ever since I’ve been on here. If it had been maintained properly, Grenfell Tower and the finger blocks are quite beautiful. Particularly if you live here. I don’t know the architect that designed them but they have architectural merit. I don’t know how you say you love your home. You love your home. If we remember what happened in 1974-75 by the signs, Get us Out Of this Hell, then maybe the Grenfell Action Group blog, the protest that we did going up to Holland Park Opera, the procession of Westway 23 along the Westway, will be things that in 25 or 30 years, people would look back and say, when they took away the stables, the Westway Stables, when they took away the children’s centre, didn’t people say anything. And they get on the computer. Look I found this Grenfell Action Group. Yeah they did something, And they did this demo. That will inspire the next generation of people who would care about their community. Clare Dewing, resident of Talbot Grove House: My parents were squatting in and around the area. Mum became pregnant with me and said right Paul, get us a flat now. My first steps were actually in the flat that I live in right now which I share with my mum. When my mum walked into an empty house, she put me down. I stood up and apparently I ran just clean straight across the room and those were my first ever steps. Growing up on the estate, we were told never to leave the estate because I’ve always viewed the estate as two halves. My half which is Talbot Grove house, Verity Close and the other half, the finger blocks and Grenfell. So when we were a bit naughty, we used to go on the other half and do knock down ginger and stuff like that. I did probably knock on Christine’s door. About 1993-4, I was quite naughty and I’d be going to clubs, sneaking out. Mum and Dad wouldn’t know and my friend would say she’s staying at my house and I’d say she was staying at her house. Teenagers you know. I do remember it being quite scary trying to sneak back into Ladbroke Grove and we got mugged a couple of times, got followed a couple of times. But in recent years, I do feel the safety has improved. There used to be crackheads on every corner, all along Portobello. But that kind of edginess gave it a vibrancy which unfortunately, I think, it’s almost gone. About 5 years ago unfortunately my dad became ill and I moved back to my parents house to look after my dad. We’d always known that my mum’s memory wasn’t too good. But it was only after my dad died that we managed to get her to have a full proper diagnosis that it was early on-set dementia. Mum’s going well. I think the progression of her dementia has slowed and I think that’s down to a combination of exercise, good food, good stimulation. I wanted to join the R.A. because it got me to kind of flex my muscles again in using organisational skills in a different way and and just giving back to the community that’s helped me out so much over these last few years. Kensington and Chelsea are an amazing borough to live in especially the way that they look after the older population. I also had a bout of depression as well and the services that were available to me are not available to some of the people that I’ve spoken to. So I feel that the support is there and that’s why I’m really surprised about the state of the housing here. It doesn’t marry with my experience of all these other services. I think Kensington and Chelsea need to be aware that if they just sell all the properties off and make it into a million plus houses, that what draws people here, what draws people to Notting Hill, what draws people to Portobello, would just be gone. It is that mix of culture that drew people here in the first place. That made it trendy. That made it hip and cool to hang out on an evening. It’s just going to turn into Kensington High Street and be replaced by Cafe Nero’s and shoe shops and places you can’t actually afford to shop in or buy food in. What we are trying to do as a RA here is to lay the foundations now. We're trying to get ourselves prepared and ready so that when the regeneration does come that we are ready and we've got some ideas together. Hopefully we can influence them which would be great.

9 Comments

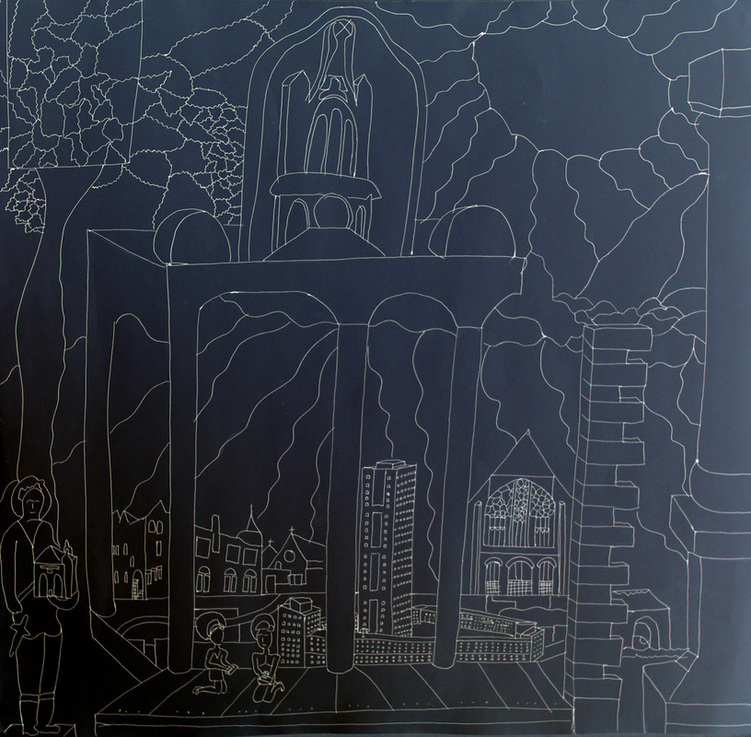

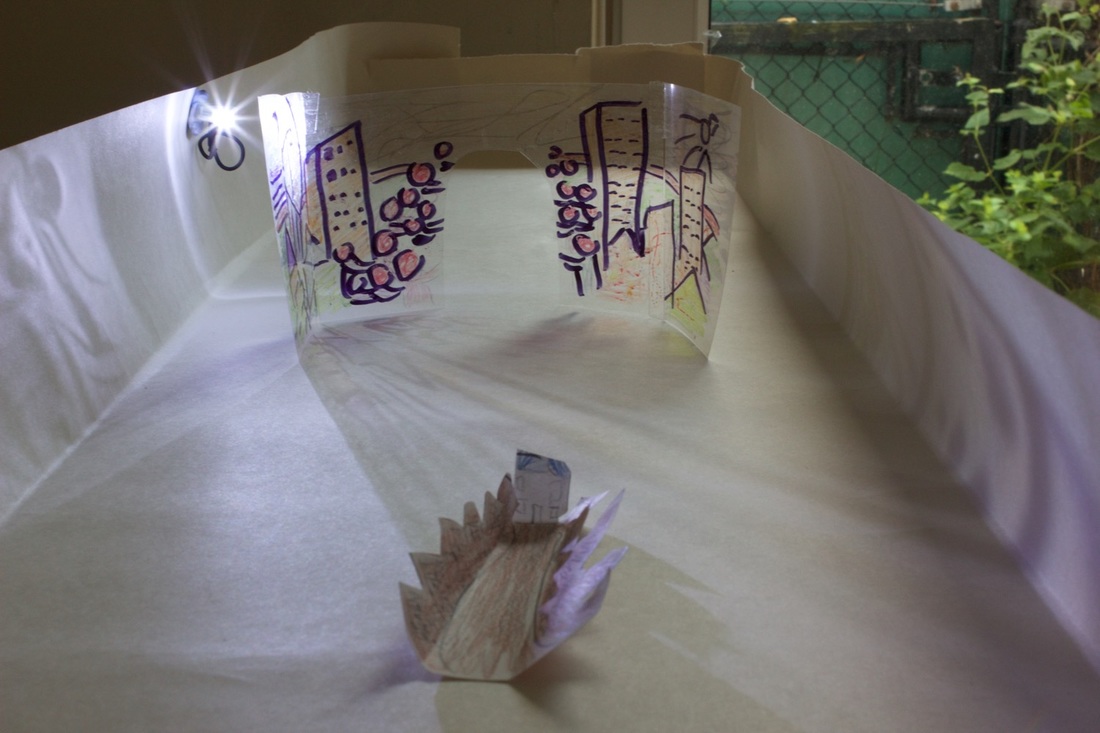

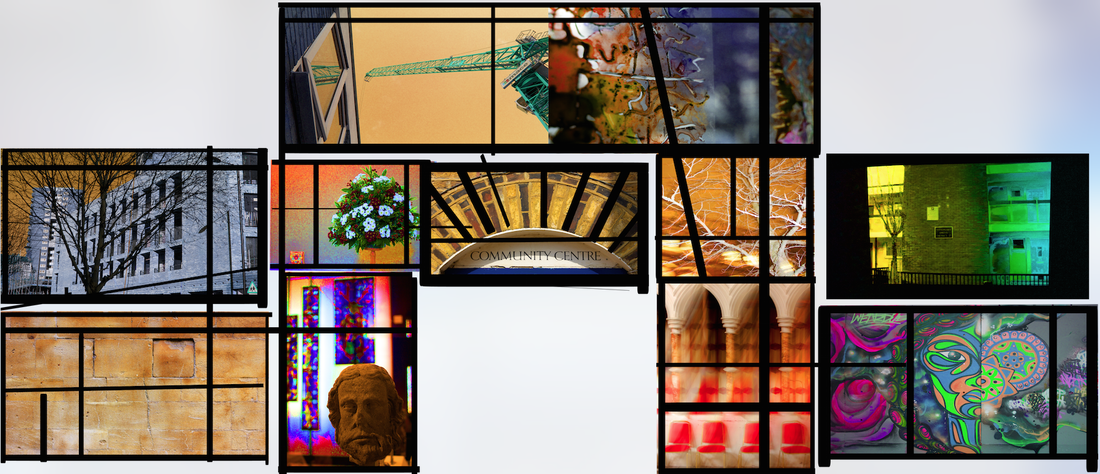

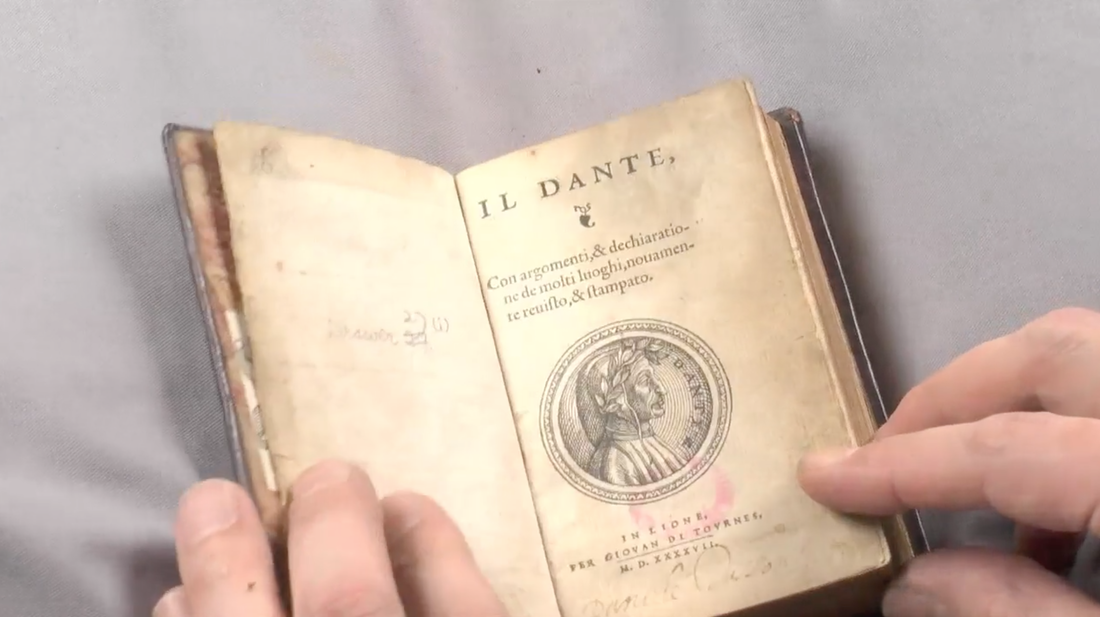

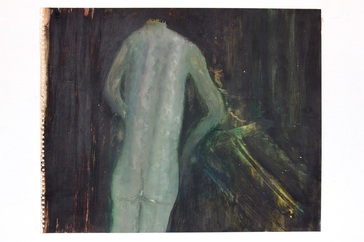

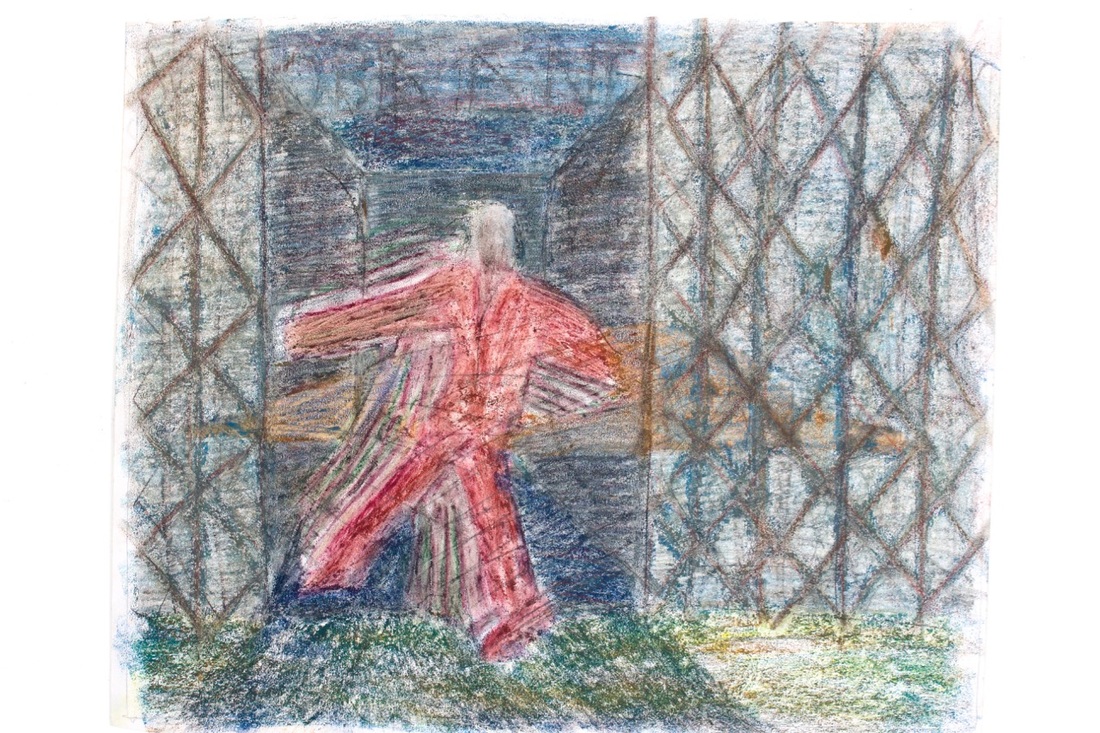

There is a corridor sized gallery at the V&A that I am forever drawn to. Literally, in the sense that I love sketching here. It's the Sacred Silver & Stained Glass collection in room 83. During my tenure as the museum's community artist in residence, I used stained glass to meditate on contemporary housing issues. Nathaniel Westlake's magisterial panel at the V&A, Vision of Beatrice, inspired an installation and artist film. The Westlake stained glass panel was made for a V&A exhibition in 1864 and was possibly conceived in the house that Westlake had built for him in the heart of North Kensington. The house is still standing at 1-2 Whitchurch Road opposite the Lancaster West estate and embodies the complex history of social change from the extremes of Victorian affluence and poverty to modern day regeneration and gentrification. This listed building would be a multi-millionaires paradise but has been converted into six bedrooms by St Mungo's and is a hostel for those needing support into housing and work. The house was situated just across the road from my artist studio which itself was a former council flat about to be redeveloped into More West. During my residency, I recorded an interview with Terry Bloxham who is a ceramic and glass specialist at the V&A with responsibility for the stained glass collection. I wanted to understand more about the context in which Westlake had made his stained glass panel and Terry quite rightly took me back in time. I was surprised by how the past would resonate so strongly with the way we live today: the forging of nation states; how religion can violently divide and spiritually unite; and the evolving technological and economic context to the making of art. Here is an edited transcript of our coversation: Terry Bloxham: Why Westlake? Why that panel? Constantine Gras: Why that panel? I didn’t know anything about it until I started my V&A Community Artist residency. I’m based in a studio in North Kensington that is part of an estate, the Silchester Estate. It’s part of a new housing development taking place on the estate. In the run up to my residency, I cycled around the borough, looked at listed buildings and I came across a house, just across the road from where my studio is. It’s the house that was built for Nathaniel Westlake. TB: Oh. Who be he? CG: It’s a bit of a juxtaposition from the estates. You suddenly see this listed building that was built in 1863. It was built by his friend and architect, John Francis Bentley, who later went on to design Westminster Cathedral. And they were both converts to Catholicism and collaborated on St Francis of Assisi church on Pottery Lane in North Kensington. But I was interested in this grand looking house near an estate and that's now run as a sort of hostel. It’s had a bit of a checkered history as this area of North Kensington has. Poverty and slums. Now property that is valued in the millions. TB: Where is North Kensington? CG: This part is opposite Latimer Road tube station. TB: I think I know. Basically Notting Hill west. CG: That’s right. TB: I know that neighbourhood. There’s a great reggae shop. Hopefully it’s still there. CG: So that’s how I came across Westlake. As an artist with a studio in the same area, albeit in a different century, I’m very interested in predecessors and making connections with them. And to discover that the V&A museum has a work of art that has a connection to the very streets in which I'm working. I’m also interested in a film that was also made in the local area and this is called Leo The Last. It was made in 1969 by John Boorman on the site of Lancaster West estate just prior to it being built. It’s about an aristocratic person who moves into the area and he gets radicalised by his interaction with the West Indian community. Some memorable imagery in the film involves looking through a telescope and also patterned glass in a pub that distorts the point of view. I suppose at one level, I wanted to explore or create a connection between film making and stained glass. In the sense of camera lenses and glass transmitting light and how they might be used for perception and analysing or documenting the world around you. Using fragments or a diverse range of media that can be pieced together to make a whole new work of art. And one not necessarily made just by the artist, but involving collaboration. Also I feel a little like that aristocratic character in the film. The artist as an outsider who comes into an area and interacts with the community and how this might radicalise either them or the community or not as the case may be. That is the type of thing I’m wanting to do in my community focused project work. I’m hoping to create a Westlake House at the V&A Museum, in addition to making an artist's film. TB: Brilliant. CG: Perhaps you can help me shed some light on Westlake and how and why he came to make this wonderful panel. TB: Westlake in the nineteenth century, is, near enough, the culmination of a movement that we now call the Gothic revival. And the Gothic Revival was a reaction against eighteenth century stuff and we are going to be talking about that as we progress through time. This involved a revision in the theological understanding of Christianity and also the furnishings of Christian churches. And all throughout the gothic revival period, whether you are talking about stained glass or metalworking or textiles, all of the things that were used for church furnishings, they kept harping on, we must do it in the medieval manner. And that’s why you’ve got to understand the medieval manner in order to understand Westlake. That’s why we are starting here in the medieval period. We are looking at thirteenth century glass. CG: Was this being commissioned by the church? TB: Yes. it was church law that you had to have some sort of decorative, figurative work in the church, that illustrated the Saint to whom that church was dedicated. All images in churches were meant to be instructive. People always say it’s bibles for the poor. But that’s sort of an insult, because it’s calling them illiterate. And I prefer to look at it, not as an age of illiteracy, but as an age when you didn’t need to read and write. Only a few people did. In the middle ages, TB: So here we are looking at a panel from the mid thirteenth century showing a scene of King Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus or Jermaine. It is telling you a story, an episode from the life of a real king. His name was Childebert. He’s in the middle of the sixth century and was one of the first kings in France. After the collapse of the Roman empire in the West you have all these so called barbarians moving in. You can tell my preferences lie with the so called barbarians. Various tribal groups as they were known: the Goths, the Gauls, the Francs, the Germanys, the Celts. The celts became the Brits. These groups are going to form our nation states. Clovis was one of these Frankish groups and from Frank we get France. This is where Childebert is descended from. In the panel, we have Childebert being chastised by bishop Jermanus, the first bishop of Paris. He is chastising the King because he had just been on a campaign to conquer the Spanish city of Saragossa. The bishop was upset about this because Saragossa was a christian city. Bishop Jermanus forced Childebert to build the first church in Paris as atonement for his sins and this church was dedicated to St Lawrence. This church was being rebuilt in the thirteenth century in the newish Gothic style and it was rededicated to Jermanus who by then had become a saint. CG: Can you tell me about the designs used in stained glass and the process of making? TB: Medieval decorated windows are composed of small, irregularly shaped pieces of coloured and clear glass. The idea was not to have big square panels of glass which they could make, about A4 sheet size. It was to make a sheet of glass, cut it into irregular shapes and move those shapes around to form a picture. And then those shapes are held together by lead. So it became known as a mosaic-type construction. When you think of a Roman mosaic floor, little pieces of tesserae arranged to make a picture shape. And then they are embedded into cement to form a solid picture. It’s the same thing with mosaic glass. The only painting that you have on it are the details that you can see in the hands and the face, the folds in the clothing. That’s just simple blacky-brown iron-based pigment which is fired onto the surface of the glass. Glass when made is clear. But in its molten state you can add colouring agents to it. Cobalt will make blue. Copper will make green and also red. Manganese will make a purply brown. Depending upon the intensity you can get this nice purply-brown robe or flesh colour. That is know as pot metal because you hold the liquid glass into a pot and add the metallic oxide. So you have clear glass and pot metal glass, cut into small irregularly shaped pieces, put together to make a nice, pretty little picture, all held together in this lead framework. And whatever paint you have was just an iron based pigment onto the surface of the glass to give you your details. That is mosaic glass made in the medieval manner. That is what Westlake is trying to achieve. I have to introduce another element in the manufacturing of medieval glass. Something that was a big technological revolution. I mentioned earlier that properly speaking, it’s not stained glass, it’s decorated glass. And the reason why I say that is because stained means penetration of glass or staining glass. That doesn’t happen until the magic year of about 1300, probably in Normandy. Some bright spark discovered that putting silver into oxide of some form and then firing, what it did was to penetrate the upper levels of the glass and create this lovely lemony yellow to a burnt orange colour. And the reason why that was so revolutionary was it enabled you to have more than one colour on the sheet of glass. We looked at yellow glass and red glass and blue glass and green glass that is known as pot metal glass. That is clear glass that has been coloured. Coloured glass is more expensive than clear glass. Any time you have extra processes it’s going to increase the price. We do have those few surviving documents that give us prices for the middle ages. So we know that glass coloured all the way through was more expensive. Staining it is incredibly cheap to make relative to the older way and once it comes in, it doesn’t disappear. When we get to the Reformation in the sixteenth century, Europe is torn apart by different believers or practitioners of the Christian faith. In the middle ages, remember there is only the church. There is no protestant, no catholic. It is just the church. So you have to put yourself in a time when your world, your faith is being torn apart, is being questioned by people who are very learned and very persuasive. And in some cases also inciters of violent activities and feelings. We tend to blame the whole reformation on him, Martin Luther. He was pretty moderate. You also had people like Calvin and Zinger who were the militant side of the reformation. And there was a lot of destruction and a lot of change. But in Europe today, you will still find this part of Germany is Catholic, but that part is Protestant. But fortunately not fighting each other. England’s story is different and was more violent. Not so much people killing each other, but people destroying anything suggestive of religious imagery. CG: You get a snapshot of those times at the recent iconoclasm exhibition at the Tate. TB: Yes that was a good snapshot. And we also have documents from stain glass makers, petitioning the local leaders of the city, the principalities. Saying you are putting us out of business. We used to make a living making religious windows for churches and it was just no longer allowed. On the continent they started to turn their hands to other iconographic subject matter in stain glass making. TB: What we are looking at now are products of Netherlandish workshops who mastered from the fifteenth century onwards, the art of very fine, but mass and cheap production of glass windows. These are simple pieces of cylinder glass, cut into a circular shape and solely painted. So its clear glass, in silver stain and black pigment. They are cheap. They are incredibly finely painted because this is the age of the printing press. So engravings were made and then they would be printed and they would be used as models for these stained glass workshops. So infect they’re copying exiting art works, unlike in the medieval period where they don’t have the benefit of mass produced engravings and stuff to copy. This panel is the story of Sorgheloos which is a secular version of the old testament story of the prodigal son. This guy, Sorgheloos, goes out, he inherits a whole bunch of money, spends it on wine, women and song. And in the end, all he has left is an old woman, two starving animals and a bunch of straw to eat. So unlike the prodigal son he’s not welcome back with the fatted calf. What also happens in the middle of the sixteenth century, these chemists as we would call them today, alchemists as they were known, developed more pigments that could be fired successfully into glass. In the medieval period it was just that blacky-brown iron based pigment. Now we have enamel colours. So we have the greens and all the shades. Red and all the shades. Blue and all the shades. And the yellows. CG: It must have been a wonder to behold, a sort of technicolour movie. TB: Yes it was. That’s why they were popular. Also coloured glass was expensive and enamel paints are cheaper than coloured glass. So we are now in the age of just simply painting on glass. Think of it as a transparent canvas. Because that is where we are going, painting on glass. Let us jump forward to the middle of the eighteenth century. We have aristocrats interested in the gothic. Walpole made Strawberry Hill which was his idea of Gothic. And then In the early part of the nineteenth century we start getting academics in Oxford known as the Oxford movement. They were also called the Tractarians because they produced a lot of tracts. They are looking at medieval theology and seeing it or pre-reformation theology as a more pure form of the Christian faith. They are not advocating a return to catholicism but they are advocating breaking away from the corruption that crept into the English church in the eighteenth century. Shortly after, a complimentary, although at times, rival group, grows up in Cambridge known as the Cambridge Camden society, but also known as the Ecclesiastics when they are sitting in London. They were interested in pre-reformation theology, but more importantly in pre-reformation architecture and church furnishings. So you have in Oxford, the academics looking at theology. In Cambridge, they are looking at the physical structures of the furnishings. So we are at the beginning of the nineteenth century at that time when people are looking back to the medieval world and things done in the medieval manner. So this is where the Gothic Revival begins. Also in 1824 the Government passes what became known as the 600 churches act. Christianity had fallen into corruption in the eighteenth century. The church fabric itself, the buildings were neglected. There were a lot of people assigned as clerics in churches who just stayed in their country estates and took the money and they didn’t even maintain the churches. So the government steps in and makes a proclamation, effectively going, thou must build churches. Into this comes the great architects like Butterfield, Street, Pugin. So the very first half of the nineteenth century is what we know as the Gothic Revival. Church building, church furnishing going on and stained glass starts apace. Also in the 1850s and 60s craftsmen were thinking why can't we do it like the medieval stained glass makers. They couldn't simply because medieval glass is mouth blown. So there is no evenness in its thickness. Each bit of glass that the medieval craftsman made, this bit is thin at one end, but it might be thicker at the other. So that when you put it into a window and light comes through that little bit of glass, the light will come through differently. It will be less bright in the thicker bit and more bright in the thinner bit. The medieval craftsmen knew that. That's what the Victorian stained glass makers were really trying to discover. TB: Nathaniel Westlake was a freelance designer. You could make a living by doing that. He went around to companies like Powell’s who were probably the biggest manufacturer of windows at this time. He would show his portfolio of how good an artist he was. Also a portfolio of stained glass design that he could offer to them. And that is how he was making his living. But in about 1858-59, clearly by 1860, he had become involved with the stained glass firm of Lavers and Barraud. In 1864 the V&A had an exhibition of stained glass and mosaics and one of the firms that submits things that were selected to be displayed was a panel made by Lavers and Barraud to the design by Nathaniel Westlake. So this is just made for an exhibition piece as far as anyone has ever been able to find out. It wasn’t actually a potential commission which a lot of exhibition pieces were. This just seems to be solely their own making and as it’s a design by Westlake, one makes that big assumption that it’s Westlake’s idea. The iconography of this panel was all in his head. We know that Westlake was friends with the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood like many groups in Europe were interested in things medieval. They’re looking at more literary subjects. Morris and co were doing lots of things like George and the Dragon windows. Dante Alligheri, the writer of the famous Divine Comedy, from the early part of fourteenth century was big. There was a lot of interest in him. The iconography of the Westlake panel is quite complicated. It is derived from Dante’s Divine Comedy. In this poem Dante was granted a trip through hell into purgatory and finally into paradise. It’s a wonderful story. Dante is lead by the Roman poet Virgil who to him represents reason and as Dante is going through hell and purgatory he is reflecting on his own life. He is working out his own sin. At the very end of purgatory, this person called Beatrice starts to be mentioned. Beatrice was a real person, Beatrice Portinali. It seems that Dante knew her when they were children in Florence. He was a member of one family and she was another. For whatever reason and remember Italy wasn’t a unified country, it was a bunch of city states and these city states had noble families fighting each other. So marriages were not love matches, they were political matches and Dante had fallen in love with this young Beatrice. Madly, head over heels, quite perversely. Like, get over it Dante. But he never did. But he couldn’t marry her. She married someone else. We don’t even know if she realized his devotion. But anyway she had to marry someone else and she died quite young. So he was stuck on her all this time. Now when you read the Divine Comedy it becomes apparent that Beatrice is divine love. And divine love is the only way you can go through heaven. Reason cannot take you into heaven. So at the very end of purgatory, before he makes that last crossing of the river and going up into heaven, Dante is given a vision by a woman called Mathilda and her companions, often known as the three graces, but really faith, hope and love. They give Dante a vision of what is to come. And this is the first time that he realised that this woman, who he has always loved and is now dead, has become divine love. This vision of Beatrice is going to lead him into paradise. This is what is depicted in the panel designed by Westlake. Beatrice up there in that top left corner. Faith, hope and love are those three figures who are often referred to as the three graces. First personified in that form by Sandro Botticelli in the middle of the fifteenth century in the Primaevera painting. This is Dante kneeling at the front, eyes closed, given that vision of Beatrice. That moment when he realises that his love has become divine love and so will take him into heaven. It’s done in the medieval manner. So we’ve got little pieces of glass just like in the medieval way, irregular shaped pieces carefully chosen. It’s not just take that one, put it there to make the picture, but trying to get the right balance of light coming through. By this time in the nineteenth century they are using the equivalent of light cables. So they can start to see the effect and so they can choose the glass, arrange the shape in order to maximise the light coming through. So Westlake is the culmination of this late eighteenth century, first half of the nineteenth century, Gothic revival way of doing it in the medieval manner. He is a medieval craftsman. He is a medieval artist. Let’s put it that way. Lavers and Barraud are a workshop that operated in the same way as a medieval workshop would have done. You have a centre in which you had your designer, your painter, your glass maker, your lead worker, all in one institution producing the window and each one being prized for their skills. As the nineteenth century moves on the designer becomes more of an artist. You start to get into, what is known in the ceramic world, as art pottery. You might as well call it art stained glass. Four film stills from Vision of Paradise, 2015. 30 minute, high definition video.

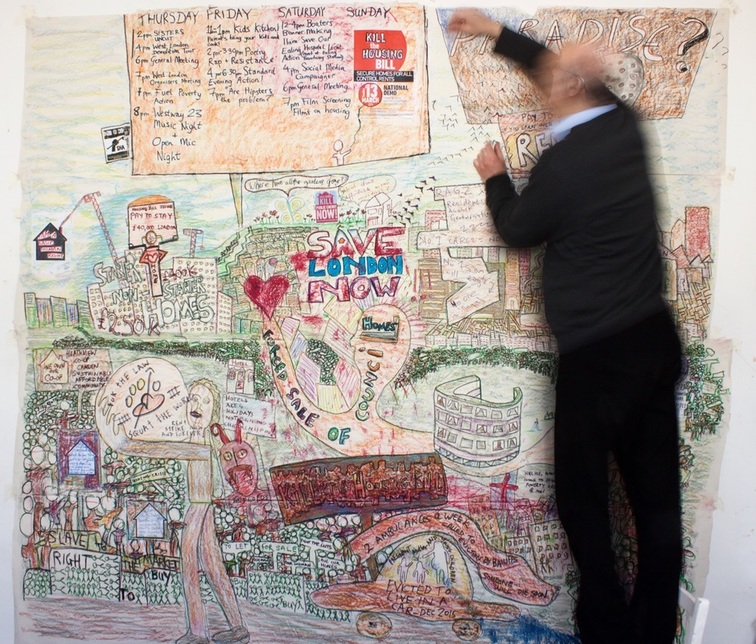

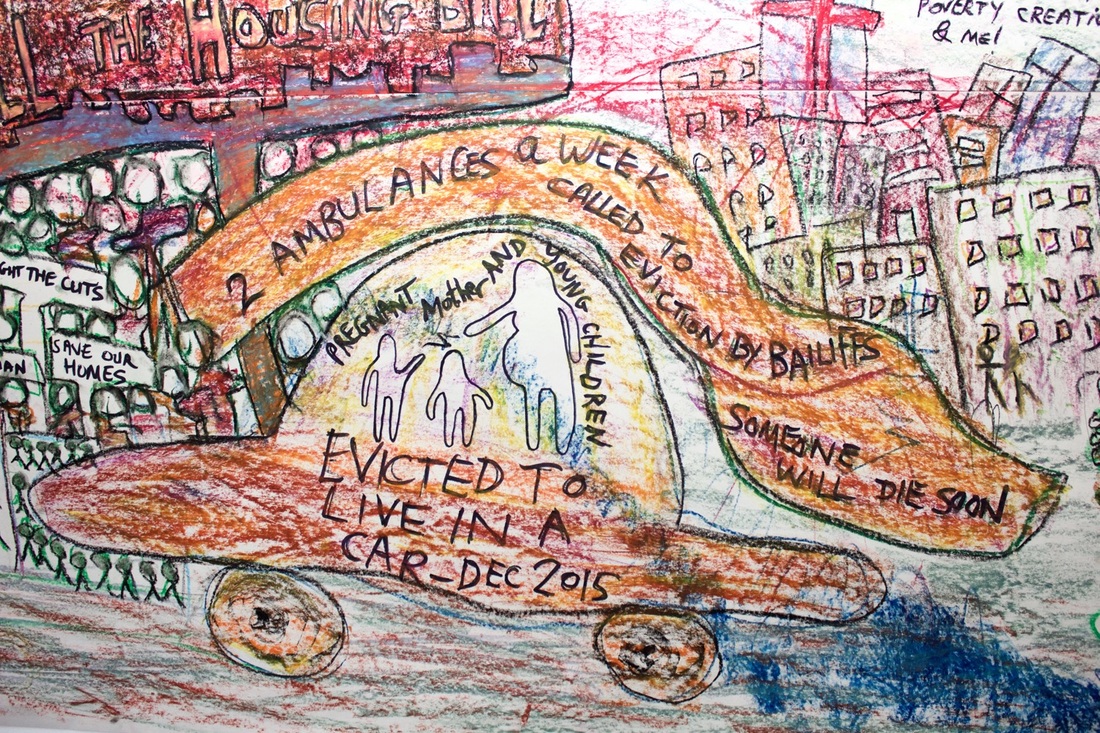

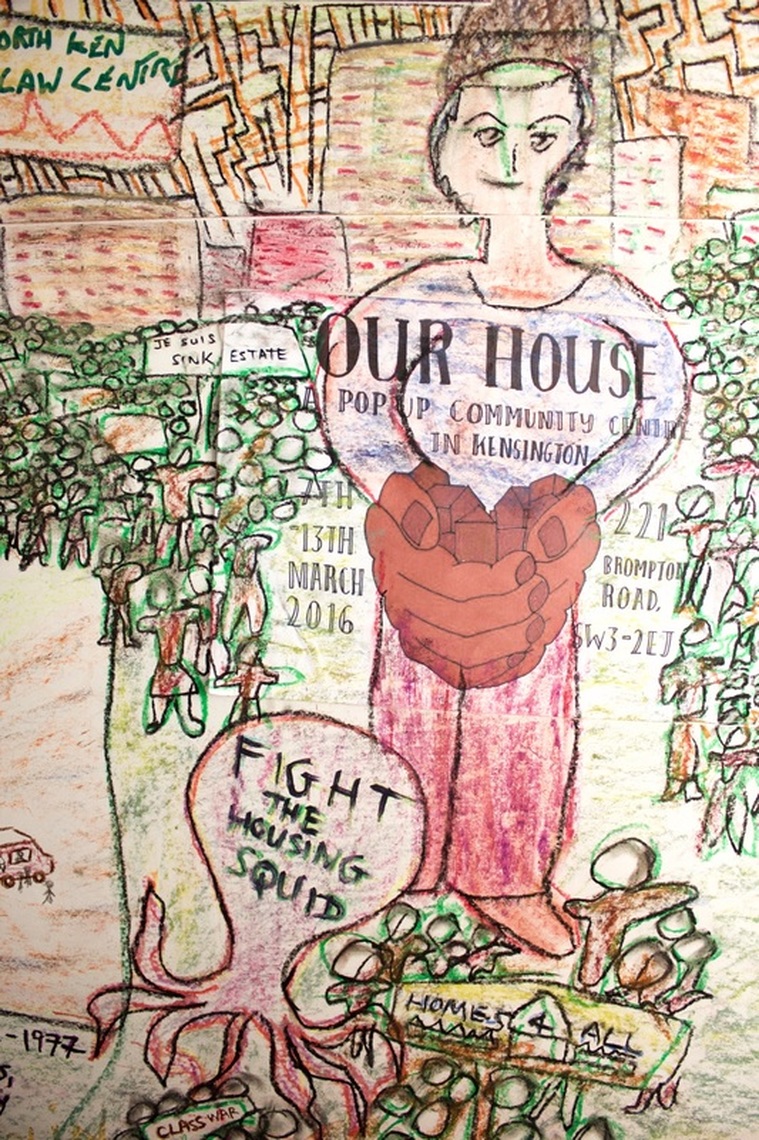

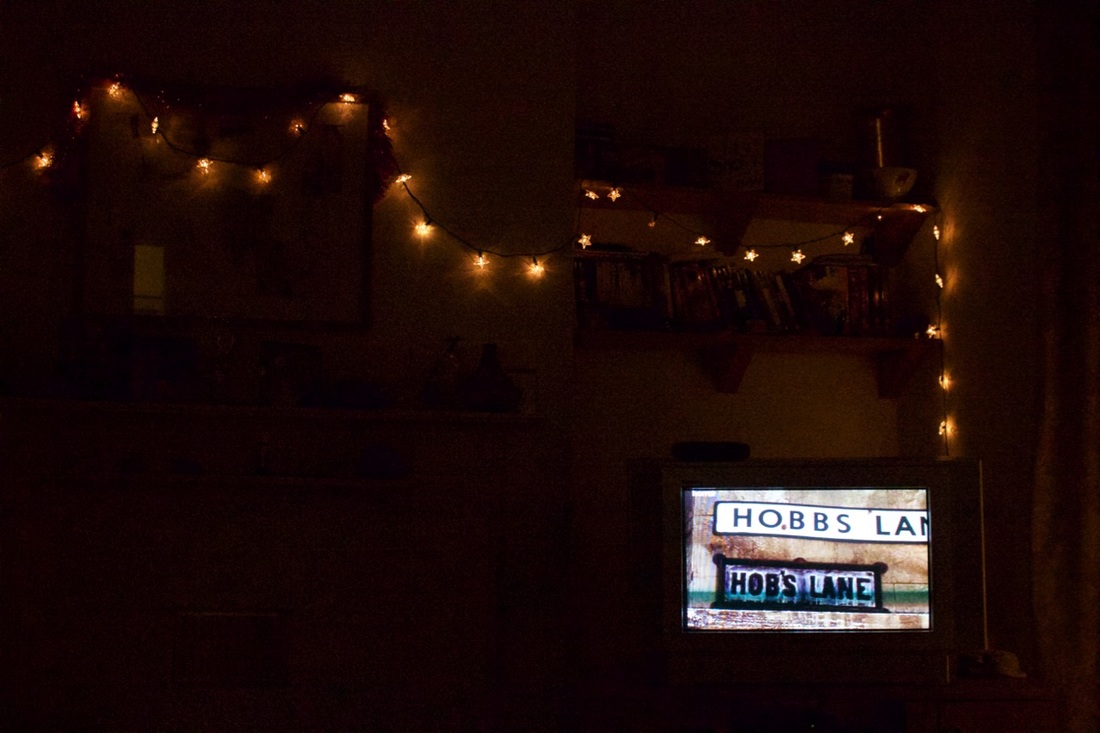

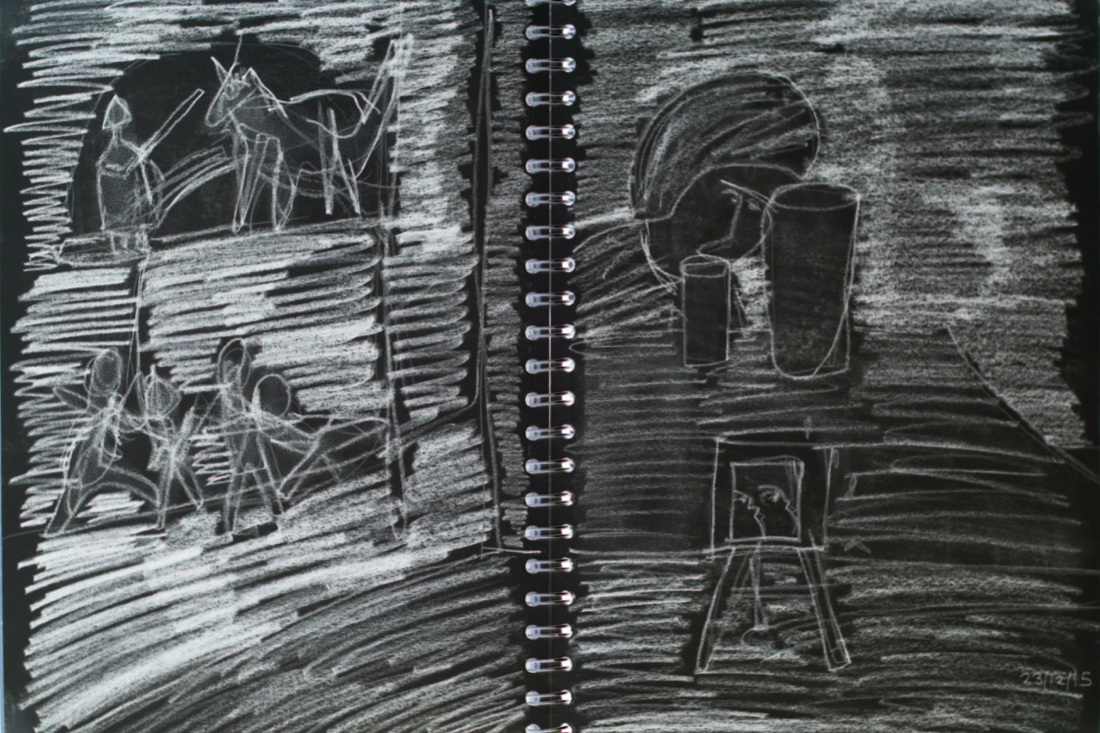

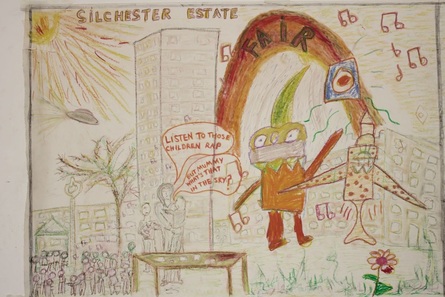

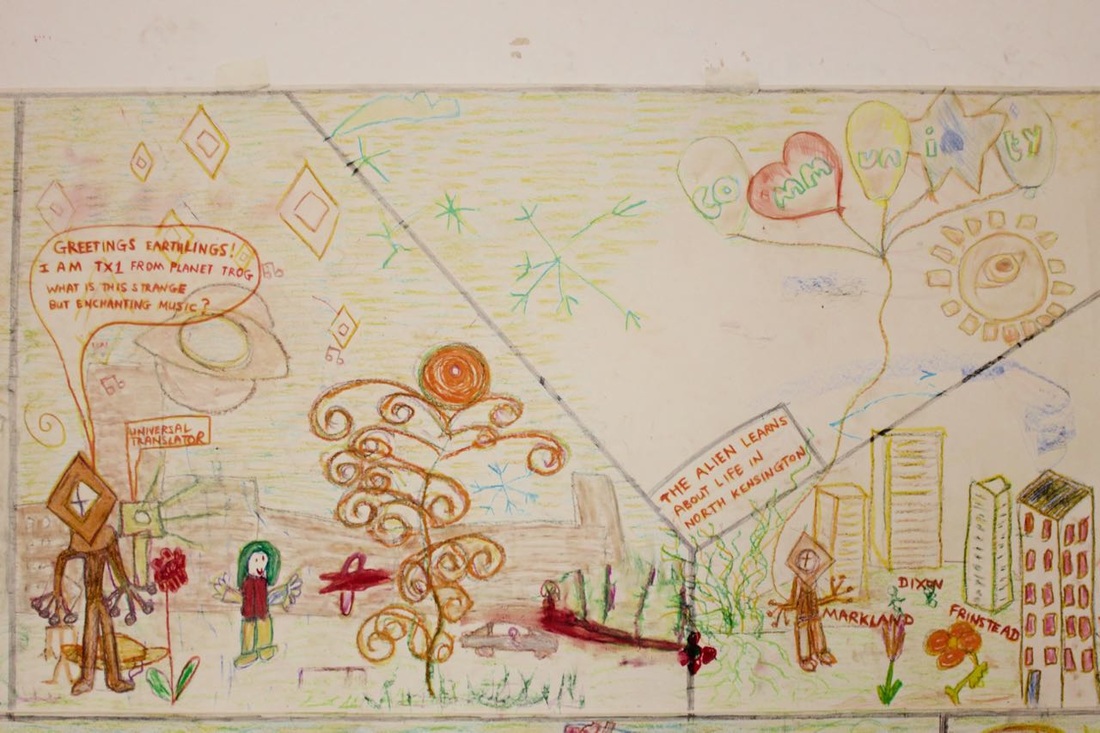

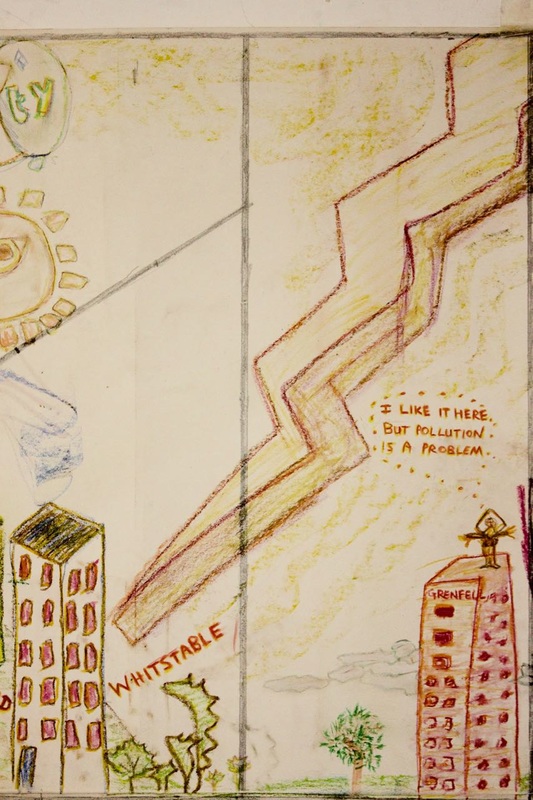

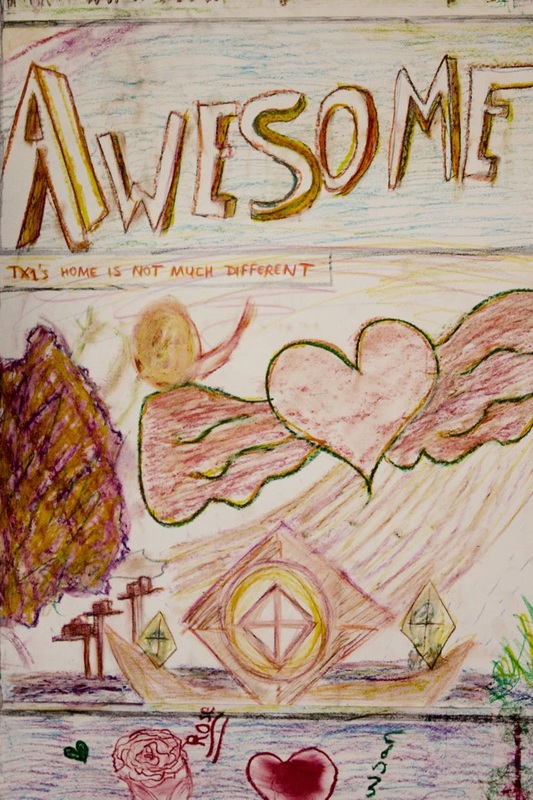

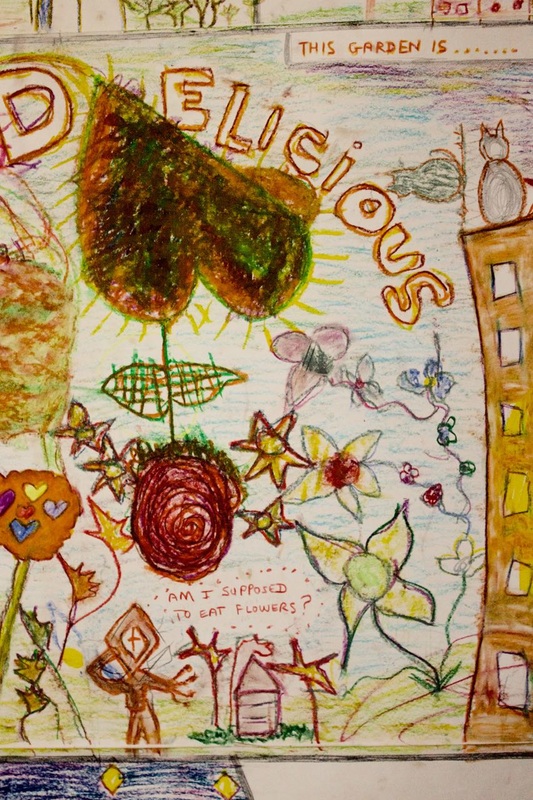

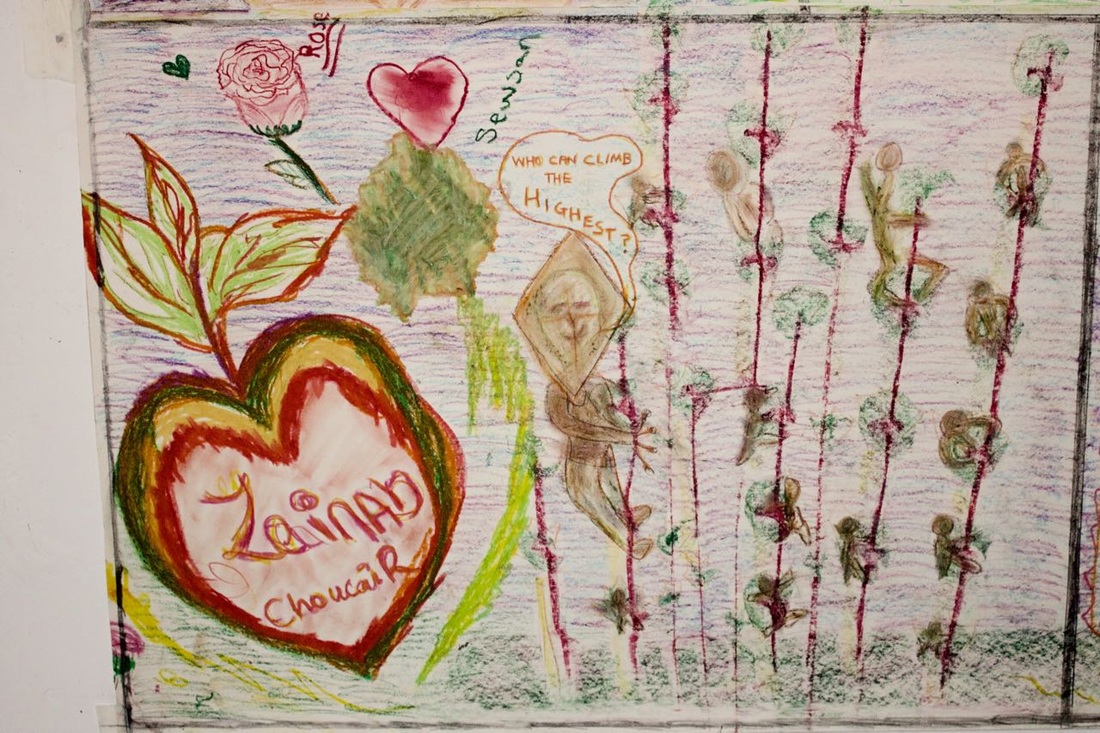

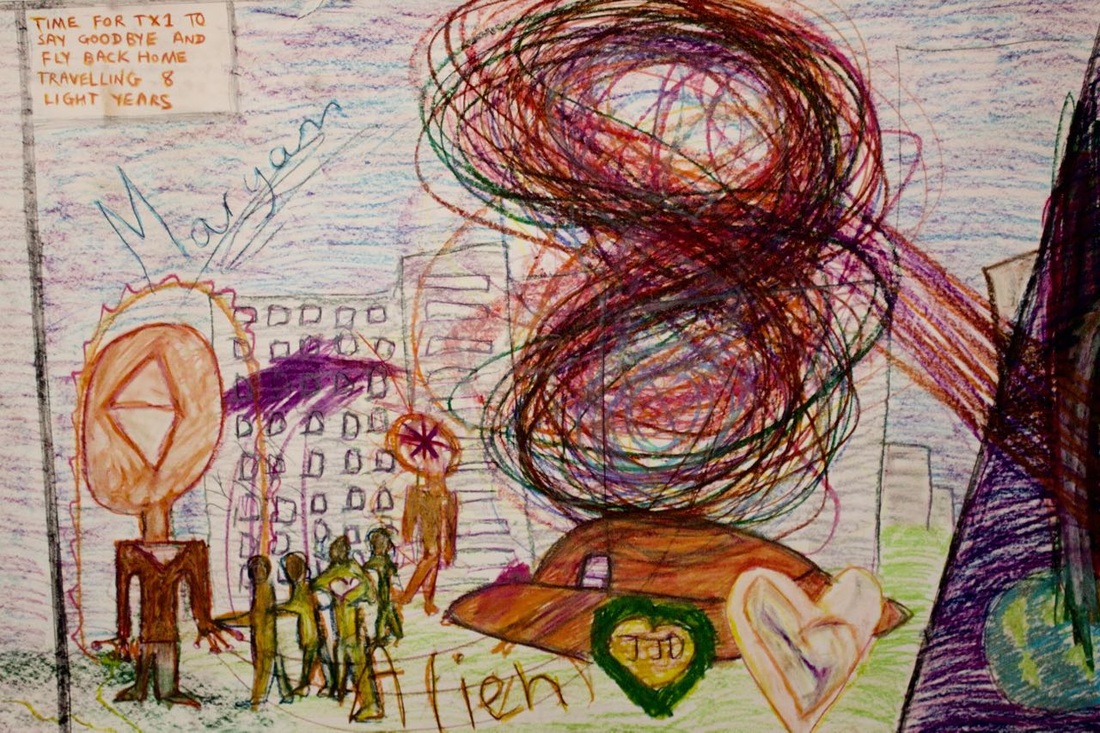

The green Gras is radiating a little less green and vibrant these days and this not necessarily attributable to the ageing process with a fading of optical and aural powers. I have climbed onto a plateau and am now looking back on those 25 plus years spent in the valley of labour. I can just make out my former self as a speck on the horizon. Zooming in we see a late bloomer who is negotiating the well-worn path of part-time jobs to fund the writing, photography, drawing and film making. There is energy exerted in between bouts of inertia. A transformational moment occurs in 2008 with a resolve to become a full-time artist. Patience, practice and process are now married with project work. Making others share in your ideas and securing funding to make these dream come to fruition. Successful projects include eco work for the Cultural Olympiad and a recent V&A community artist residency that allowed residents of North Kensington to connect with the museum on the theme of regeneration and social change. All peaks are followed by troughs in the valley. One such is Birth Control - a site specific installation about the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre that failed to secure Wellcome Trust funding. I have compiled a selective slide show of all those shades of Gras with drawings and photos that span from 1984-2016. The artful "selfie" has always been an intrinsic part of self-reflection, role-play and a desire to establish points of permanence (or the illusion of closure) in a rapidly changing world. These images show a movement from youthful, solitary immersion in a photographic dark room to the collective joys of drawing with oil pastels. I'm just getting into my stride and being an optimistic soul, look forward to the unknown challenges in the next 25 years. I am a basic human right The Radical Housing Network recently set up a squat and pop up community space ahead of the national demonstration march against the Housing and Planning Bill that was held on the 13th March 2016. In response to these issues, I started a large scale drawing. It began very quietly by allowing others to interact and collaborate. The first mark was made by Edward Daffarn from Grenfell Action Group who described the issues facing the tower block he lives on at Lancaster West estate. This was followed by Colin Stone, a film maker, who made a delicate sketch of the concrete building in Hulme that he lived on as a child: "home to rise rises, poverty, creativity and me." A student from Germany registered her incredulity over the phenomenon of poor doors - a separate entrance in a housing block for those living in less expensive apartments. A toddler wandered over and struggling to differentiate the tip from the base of a crayon, made furtive stabbing motions on the surface of the paper. He eventually made a mark. The child's mother who lives in Camden at a housing co-op called Heathview was more celebratory in describing her home: "sustainable, affordable and community." The drawing was in motion. I provided more detail and joined-up colours. We had started a visual debate into the current housing crisis and the government's lamentable response in building affordable homes. How do artists and the community visualise these complex but fundamental social issues and create campaigning art work? Fight the housing squid A film can haunt you in many different ways. In 1978, an excited boy and his overworked parents trek down to the Odeon, Leicester Square. No, not the previous summer-smash Star Wars, but it's more domesticated twin, Close Encounters. Inspired by The Third Kind, he would travel home counting every twinkling light of air traffic as an alien ship passing in the night sky. A fifteen year old is skipping across the ground level section of Westway (A40) and bunking into an X-rated double bill of Terror and Savage Weekend. It's 1981 and the last gasp of the ABC cinema at Edgware Road. Young men are performing a ritual of daring each other to grin through slit throats and dismembered heads. Jump cut. That boy-teen-man is now projecting a 35mm print of Peeping Tom to sleepy film and literature students at the University of Warwick. He is anxiously waiting for cue dots to appear. After effecting a change of reel, seated alone beside a small aperture in the booth, he looks out across the illuminated heads, several bobbing down to new planes of consciousness. The projectionist is transfixed by the imagery on the screen showing a movie camera that has been turned into a deadly weapon. Yes. Those are all my hauntings and they still persist to haunt. This year of slow motion into middle age has lead to a reappraisal of the Italian director, Mario Bava. His richly lensed films were discovered online where there are collective opportunities for the young and old alike to be haunted or re-haunted. This past year has seen the passing of the great Christopher Lee. I kept YouTubing majestic scenes from Bava's The Whip and the Body. In particular, there is a compelling sequence when the heroine is being drawn to the S&M ghost of Lee down a darkened corridor by the constant cracking of a whip. Cinematic magic. As a practising multi-media artist this "haunted" quality only manifests itself in drawings and unpublished or unrealised screenplays. I share a few of the former with you. Although my lips are temporarily sealed on the latter, I do wish to share a few thoughts about a seasonal haunting, Quatermass and the Pit (1967). QM is a great British science-fiction film, bristling with bold ideas and told in a vivid fashion. The electronic sound effects by Tristram Cary, combined with effective direction by Roy Ward Baker and compelling performances, makes this a haunting of hauntings. The film is also part of the rich cultural tapestry of Hammer studios before that fizzled out in the 1970s. An older generation would have experienced the Nigel Kneale's Quatermass stories (of which Pit is the third in the series) when broadcast by the BBC in the 1950s. These are rightly regarded as landmark moments in British television. Enthusiasm aside, I want to talk about the haunting engendered by Quatermass and the Pit. This has a very specific past, present and future. Past tense. I have a ghostly memory which can be precisely dated to Christmas Day, 1973. This turbulent period in British politics would see industrial disputes, three day working weeks, power cuts, and a country grinding to a halt. I can still feel the bones of those darkened and cold spaces. This was the perfect setting for an impressionable seven year old to be spooked on Christmas Day when Quatermass and the Pit was shown as the main late night adult film on BBC2. I seem to recall watching this film alone. Where had my family disappeared to? Had they been swallowed up by the gut of seasonal excess? It matters not, for the film exerted a pulsating grip especially in its claustrophobic evocation of the London underground where a mysterious object is discovered and which unleases atavistic impulses in the human mind. Present tense. As a homage to that 1973 haunting, I decided to photograph a recent transmission of Quatermass which took place on 20tht December 2015. Towards the end of the film, the television underwent a spectrum change with its cathode ray tube. The green light waves completely swamped the reds and blues. I am still trying to interpret the significance of this haunting and I present documentary evidence for your perusal. The TV box on the following Boxing day was as right as rain. Future tense. Quatermass and the Pit is older than Time Lords and Jedi knights. It is begging for a new leash of life and I wonder if the current Hammer Films might be thinking about a re-make. If they do, they will be hard pressed to beat the original TV and film adaptions. Special effects will be a different kettle of fish however. Hopefully a new generation of writers and film makers will discovery the original and use it as source material to create their own narratives. I've just started mapping out a new screenplay called Glass Kill in which medi-EVIL stained glass is discovered in the London underground. Hauntings can come in all manner of tea cups or flying saucers and is not exclusive to the horror genre. If you want to catch a fascinating blast of gallery based hauntings, I point you no further than the sublime Susan Hiller who is showing at the Lisson Gallery until the 9th January. She has described her work as an "archaeological investigation, uncovering something to make a different sense of it." Here you will find an eclectic probing into the real and the unreal, the memory of ghosts and the ghost of memories. Of particular interest is Wild Talents (1997). This is a multi screen video installation that shows paranormal phenomena in a range of American and European horror films and this is juxtaposed with a small monitor showing a documentary about children who have religious visions. Three sets of images are unfolding in the same time and space. Haunting is all about the co-existance of past, present and future. Quatermass and the Pit airs next on the Horror Channel on: Thursday 31st December @ 22:55 Saturday 23rd January @ 22:00 Wednesday 27th January @ 22:00 What do you want to communicate with wood and bronze? The idea or emotion or desire? The repetitive action: the hammer, the chisel. The wood and bronze speaks a secret language. New inner worlds beneath the surface of touch. Space within and without as we move around the Tate galleries Transfixed by the idea, emotion and desire. I return to my studio and sketch a homage to those repetitive actions. The hammer, the chisel. Recalling my father, the carpenter. The hammer, the chisel The story so far. An alien space ship is drawn to the mythic high rise structures and Westway (A40) in North Kensington. TX1 the leader of the alien race has decided this was a suitable location to make contact with earthlings rather than equivalent structures at Stonehenge and the Houses of Parliament (too much static and interference detected at the latter).  A local ritual, a fair, is taking place on the green which the locals call estate. Those assembled are feasting, singing and dancing and the universal translator has detected a rap in Christian religious style. There is no threat level although the atmosphere contains noxious hydro-carbons which are a by-product of the engines they use in four-wheeled mode of transport. TX1 after eight light years of travel through cosmic dust and zero gravity is impressed by the colours of life, especially the shades of green which reminds her of the fertile fields of her planet. This word, cool, is used a lot and the children like the gladatorial sports, especially football. Should I tell them that their local tribe, QPR, will one day win the double? Bobby Zamora seems to be a local God. These humans live life in alternating patterns of work and domestic relaxation. The younger ones are happy to write these words on a sheet of paper: awesome, cool, delicious. I do not tell them that I cannot stomach the food they offer, it does not agree with my metabolism. But I find the flowers growing nearby very edible. Who planted these? They should be praised. As TX1 flies away from Silchester Estate and planet Earth, she takes away memories that are cool and has a few seed cuttings that will be transplanted into the soil of her home planet.