|

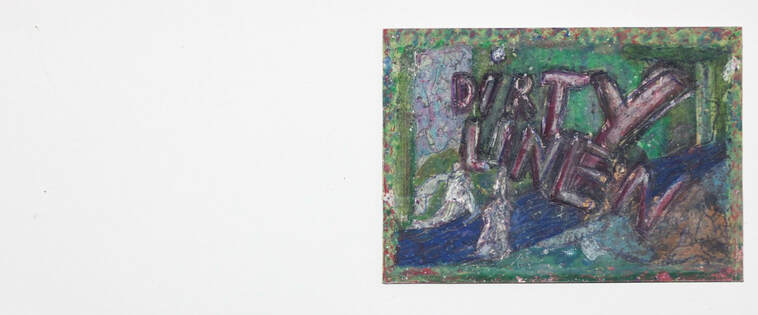

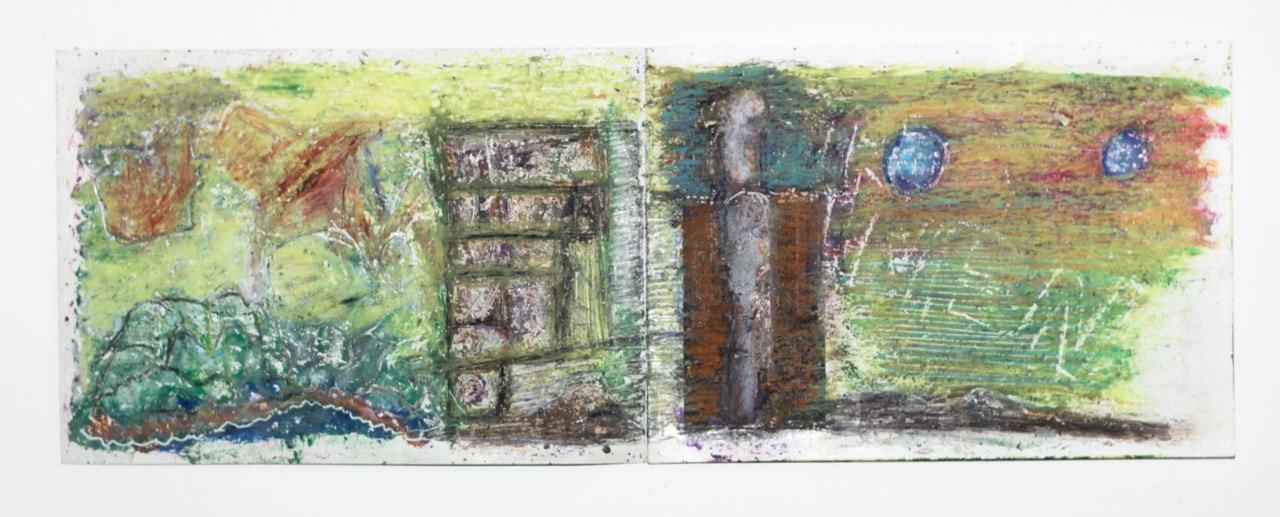

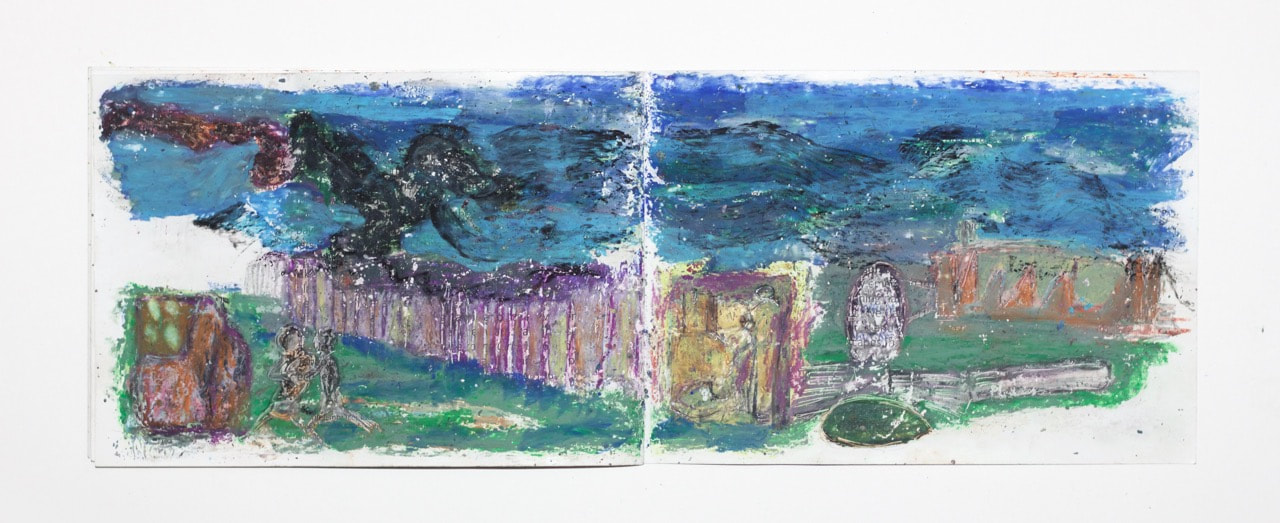

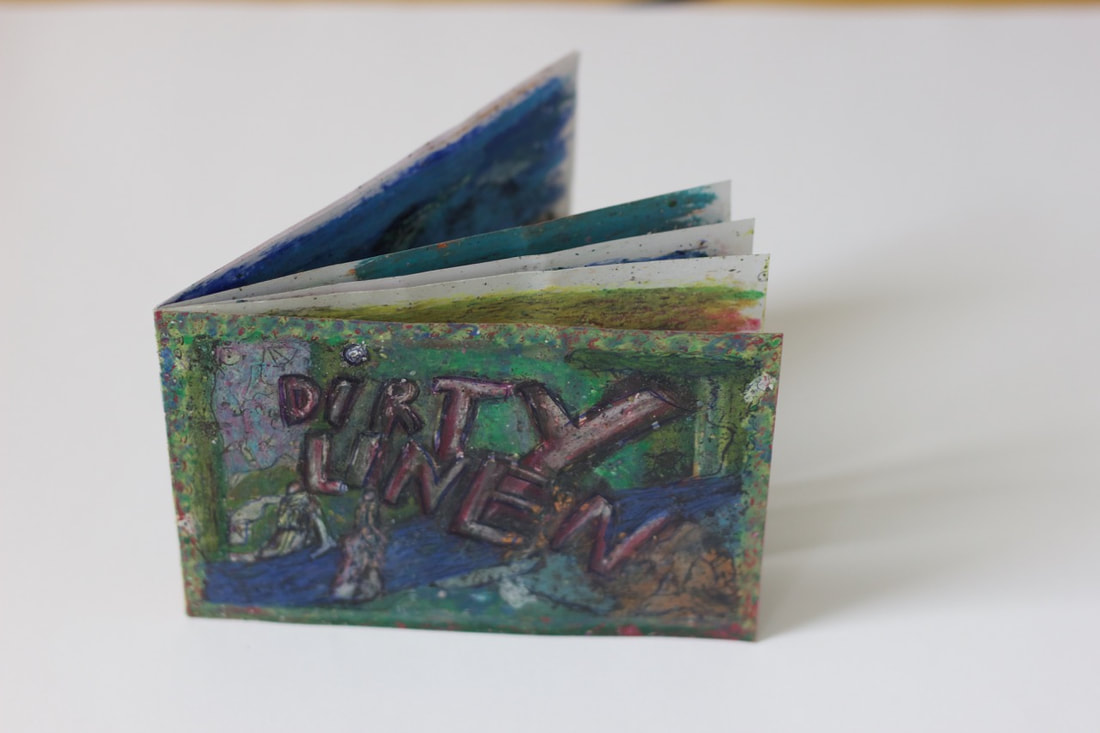

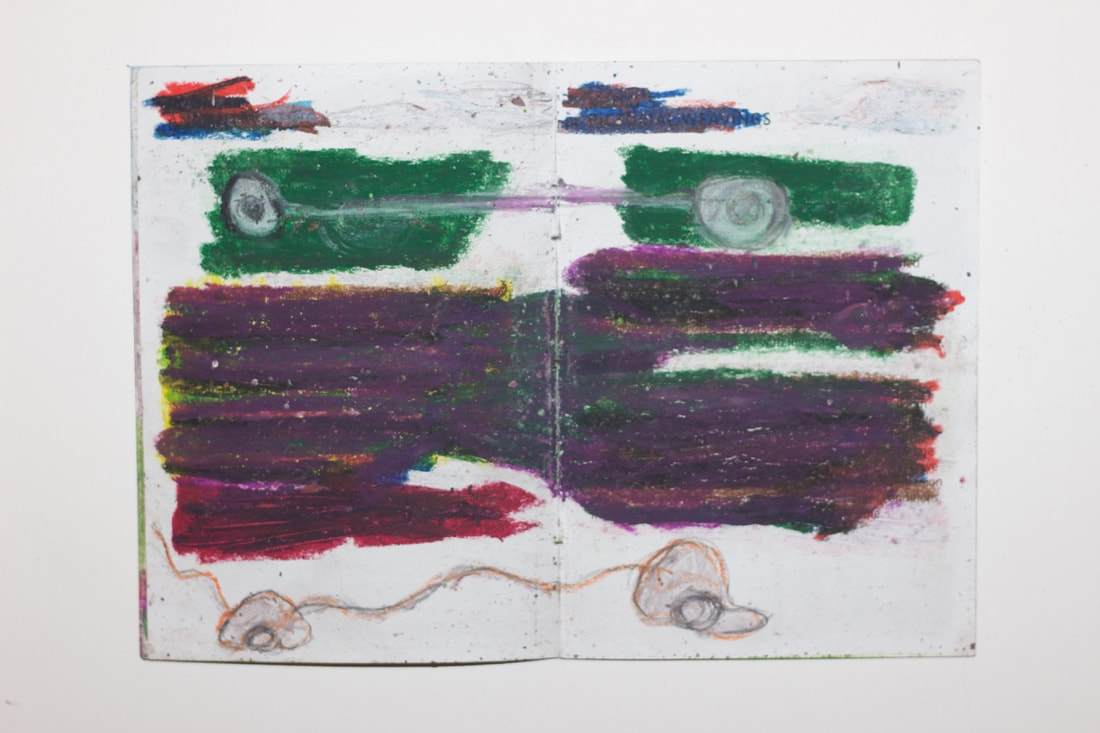

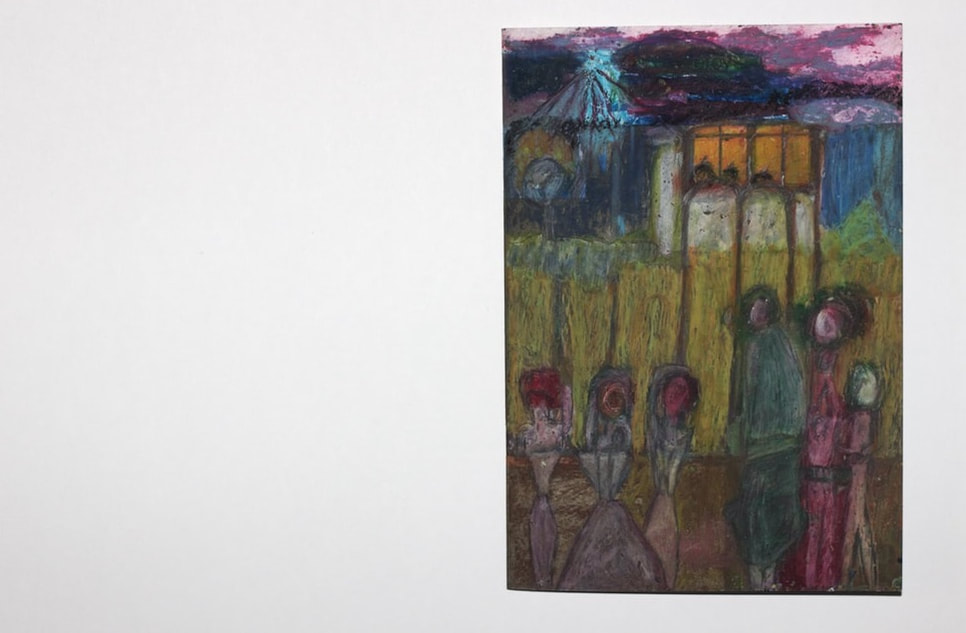

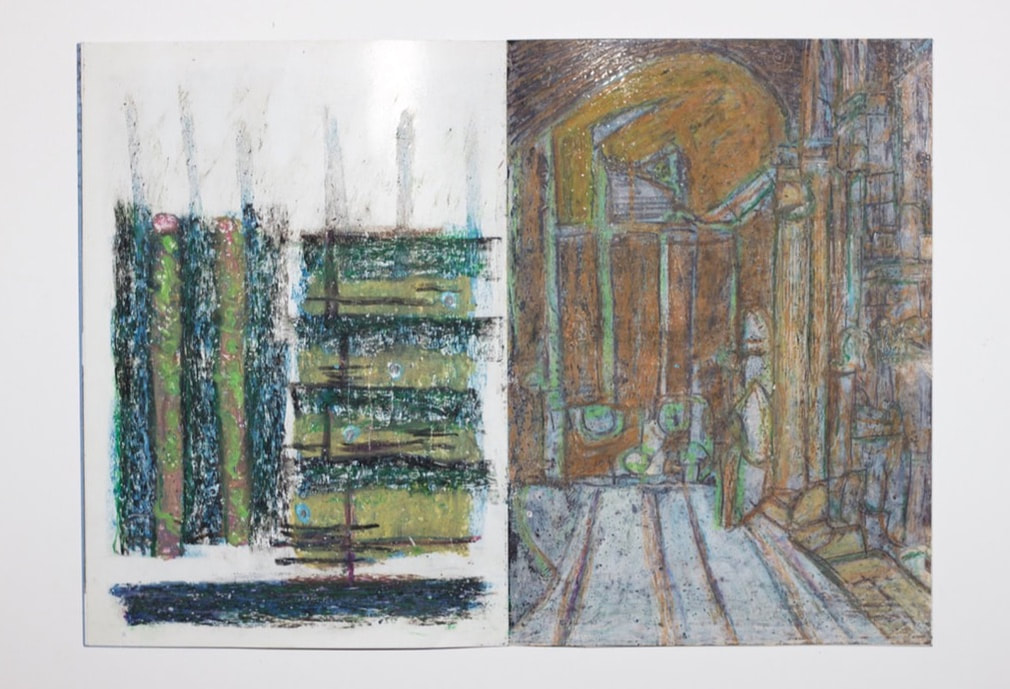

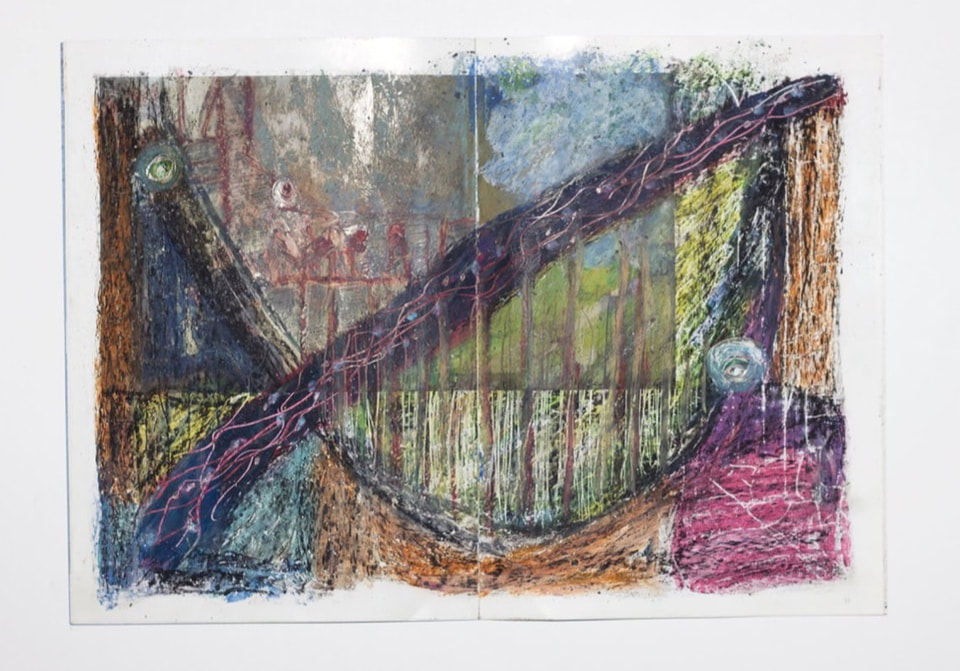

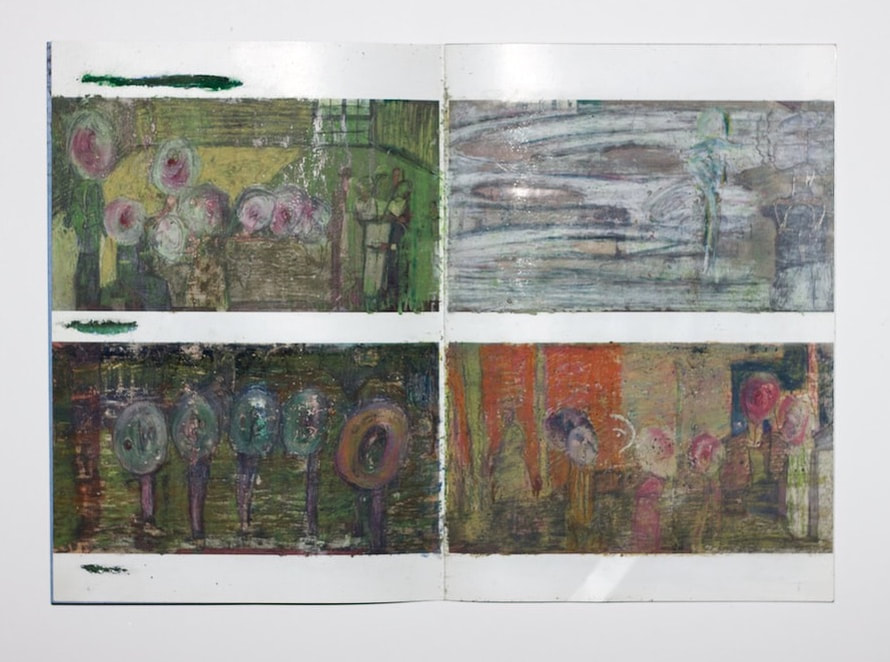

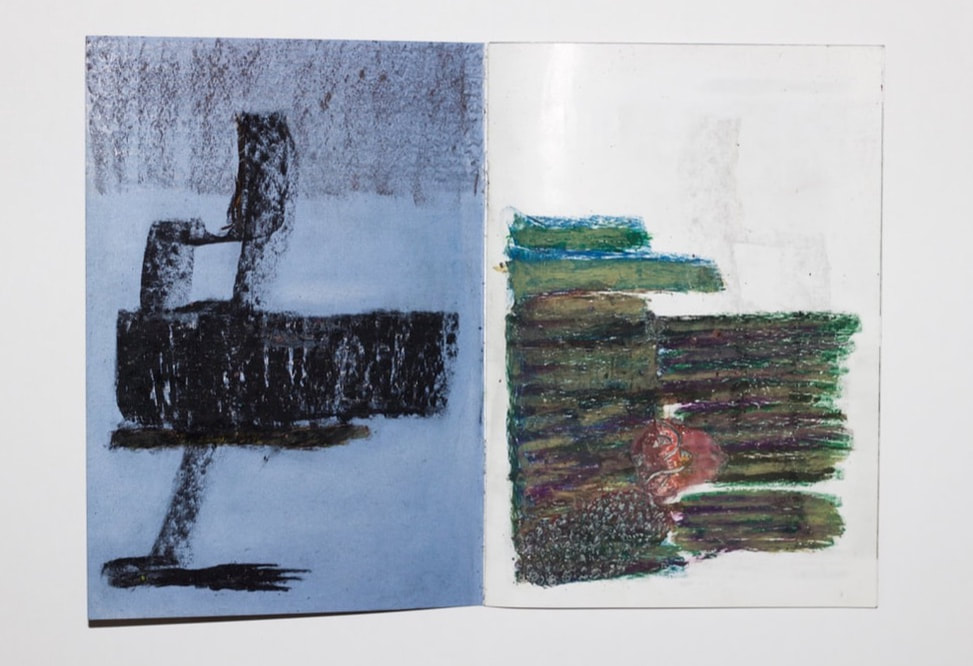

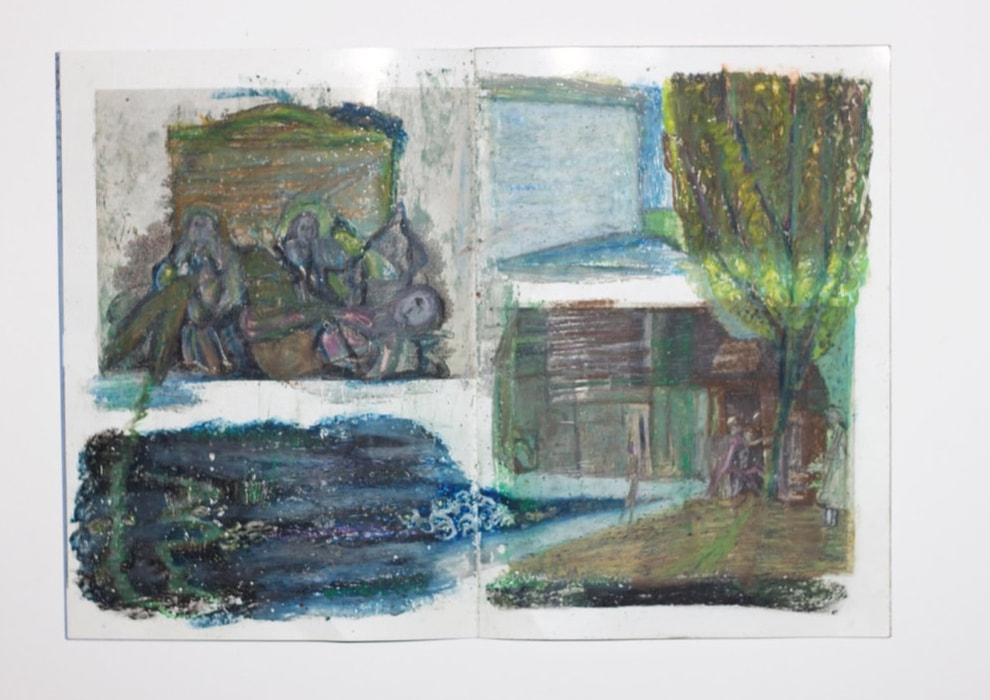

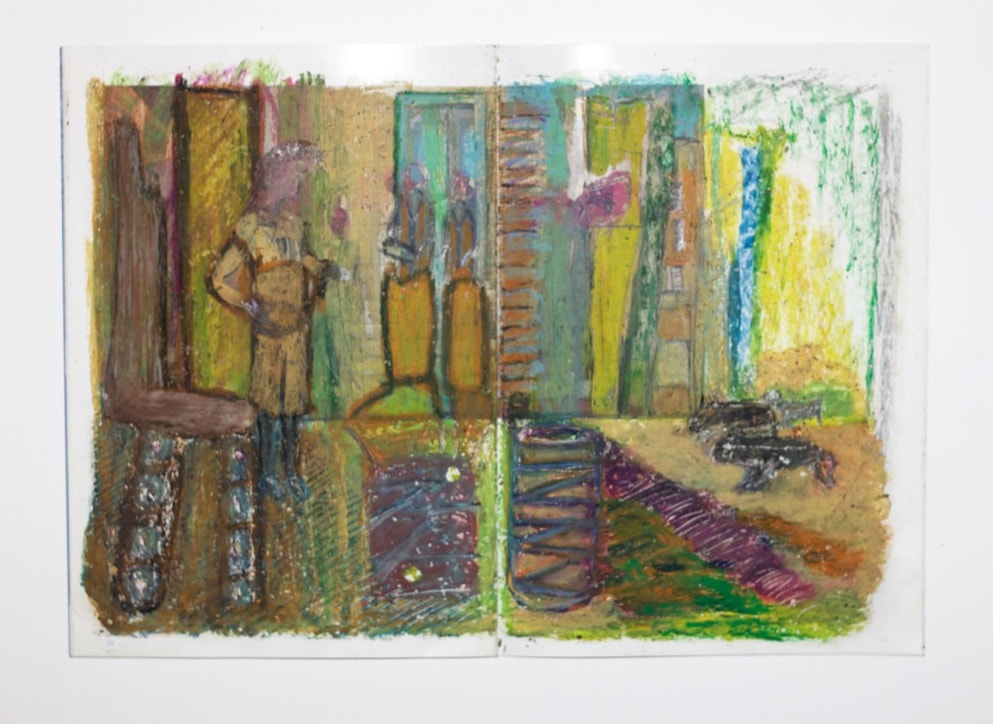

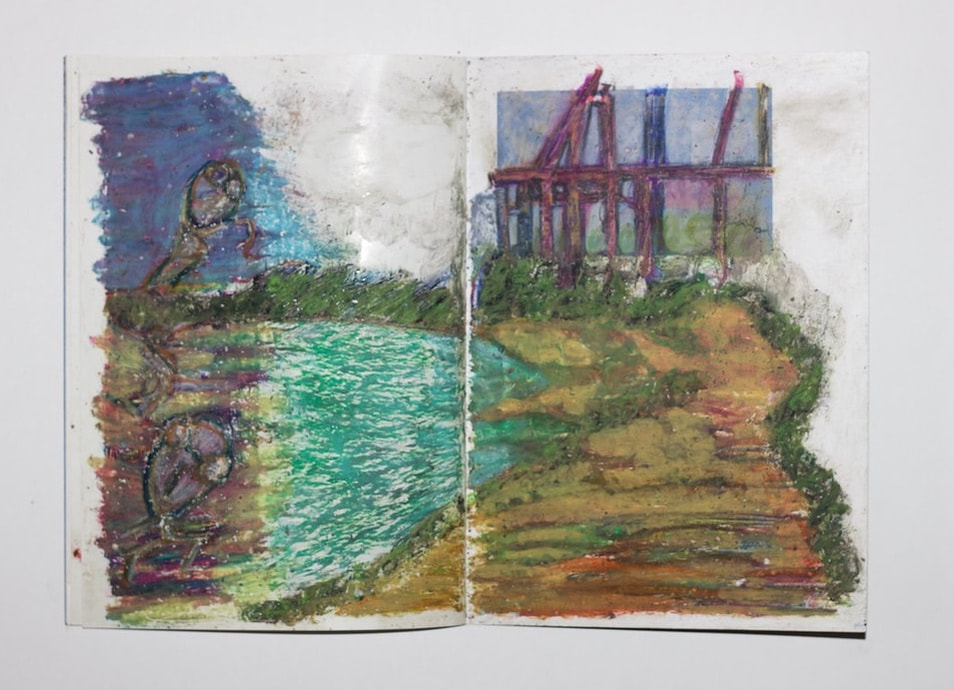

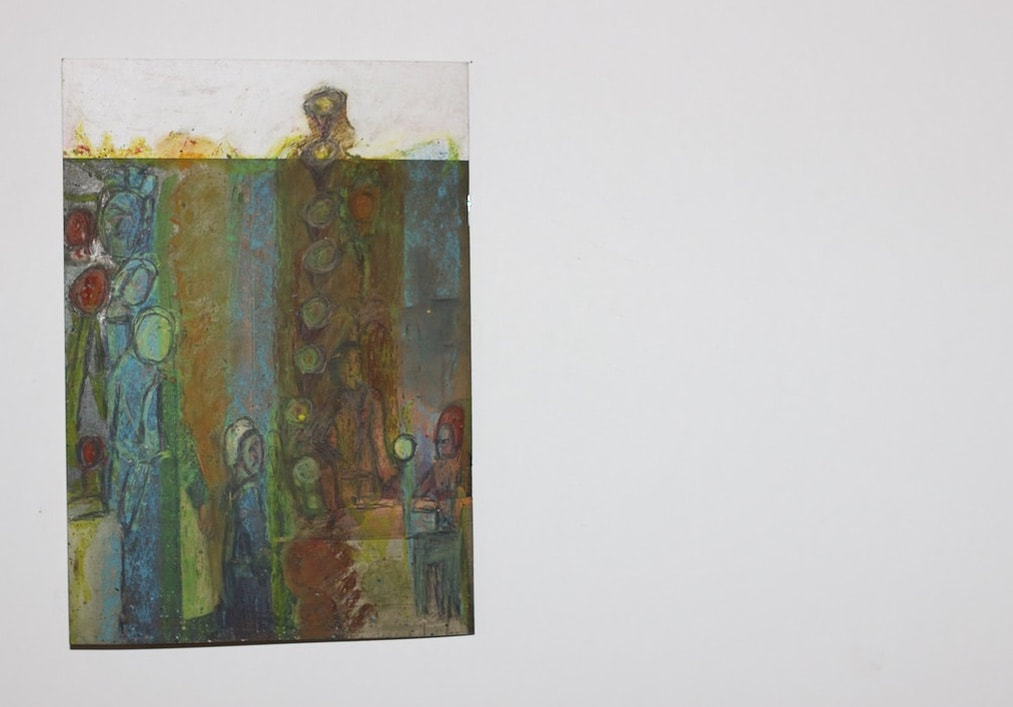

1862. Irish washerwoman at Counters Creek watches a turd floating downstream to the Thames. A 16 year old laundress at a workshop on Latimer Road, 1890. Dreaming of better pay and romance. 1924 and a depressed char lady, thinks about going to a birth control clinic that has opened in the area. V-E day in Europe and women at the Silchester Road bath and wash house sing: “We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line!” Testerton Road, North Kensington 1967: West Indian sisters are flooded out of a slum house and seek sanctuary at the bath house. 1970s: the building of Lancaster West estate and the campaign to save the Victorian bath and wash house. 1980s: residents of Grenfell tower look down on the bulldozed bath and wash house. Dirty Linen washed on 12 pages Artist's book, 6x4" Oil pastels, ink, pencil 2019 Project blog post: To marry an ironer is as good as a fortune

0 Comments

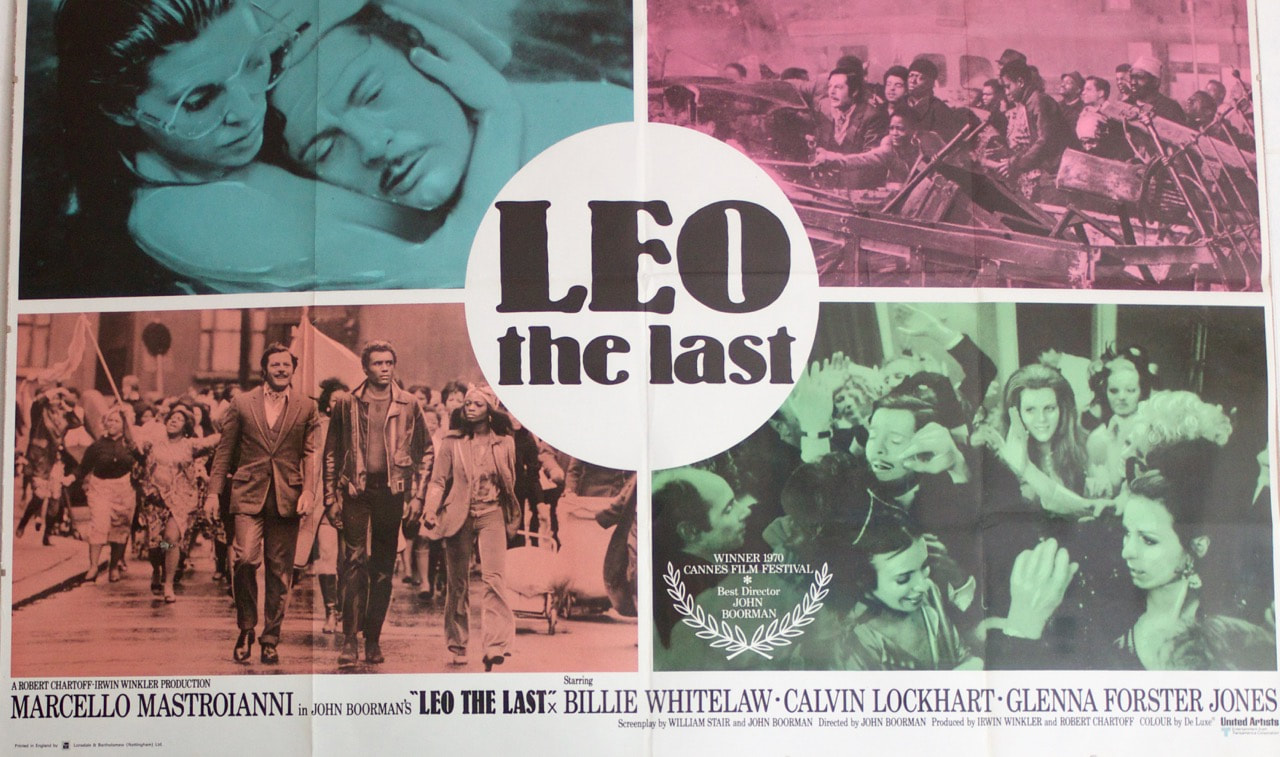

WASHING DIRTY LINEN IN PUBLIC (2019, 46 mins) SCREENING DURING THE PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 2019 On A DOUBLE BILL WITH ROBIN IMRAY'S 1974 DOCUMENTARY NORTH KENSINGTON LAUNDRY BLUES (1974, 10 mins) MUSE GALLERY, 269 PORTOBELLO ROAD, NOTTING HILL, LONDON W11 1LR

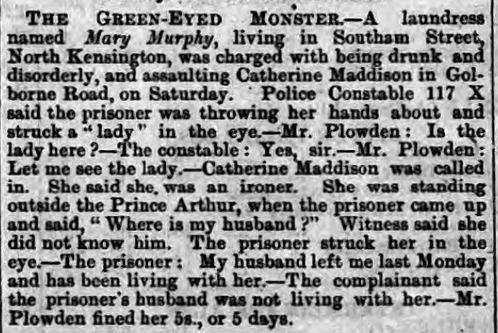

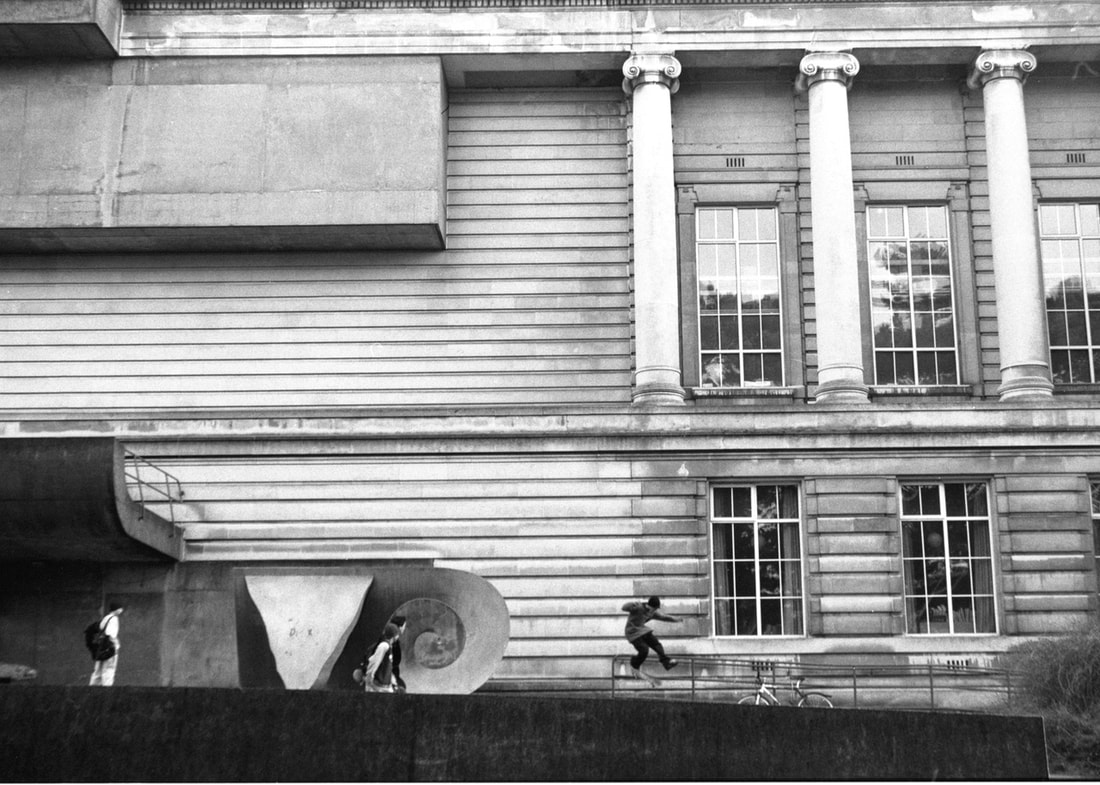

Washing Dirty Linen in Public was first performed as a guided walk and performance piece that was commissioned as part of Serpentine Galleries Hito Steyerl: Power Plants. Extracts were also staged during the Portobello Pavilion festival of art. Reviews: Jackie Blanchflower: I can't tell you how pleased I was that I gave up my Saturday morning to come to the Power Walk last Saturday. It was great to have the guided walk and performances and lovely to hear from locals who remembered the Silchester Baths and the campaign to save them. It is really good to make history come alive and of course it does repeat itself! It would be great to expand into discussions on power and powerlessness and speaking to power. Mary White: It was fascinating. There was a good sense of flow through the ages and it was inspiring to hear how women have worked together to be empowered in various ways in the area over the course of time. It made me proud to be a North Kensingtonite, and reminded me how so much of what we have today has been hard-won by those who have been activists in the past. Judith Blakeman: Well researched and beautifully acted, with a space at the end for older residents to chip in with their personal reminiscences. A very interesting and intriguing afternoon. Flora Cornish: I loved the walk and performances and social history and artworks yesterday! After building the sense of layers of history and continuity, to find there were women in the room from the laundry campaign and hear from them was the icing on the cake! Dominic Carey: I enjoyed the walk - it’s good retracing exactly where things were before the changes that I remember and things before my time like the site of the creek. An enjoyable afternoon. Well done. Edward Daffarn: It was very empowering to learn about the laundry protests from the 1970s. John Whelan: I thought it was a wonderful introduction to a story that really related to the local area. It was fantastic the way you set the scene and used the wider history as an anchor with the piece. The performances really captured the everyday lives and story of the laundry. And the music and earphones worked really well. Yvonne Allison: I was born in a family of ten children and one of the reasons for that was that my mother did not have access to birth control. And when she did go to a clinic, she was turned away because she was black. Your scene set in the house of Margery Spring Rice really brought it home to me. And the last scene as well. The one in the slum house. When my father did come to London, it was the Rachman era. It didn't matter where migrants came from, even if they were well spoken or educated. It was all the same experience for them. Watching this encapsulated the whole thing for me. Thank you so much! Washing Dirty Linen In Public was commissioned as part of Hito Steyerl: Power Plants at the Serpentine Galleries. It was a guided walk enhanced by theatrical performances and also a related art exhibition. The latter took place at Latymer Community Church on 27th April 2019. The story of women's labour and activism from 1860-1970 was set in the world of laundries and the bath house at Notting Dale. A guided walk set the scene for actresses who performed in the park at Silchester Estate, before moving on to Freston Road and finally ending up beneath the elevated A40 Westway. Once upon a time this area was known as soap-sud island. At its peak, in the early 20th century, there were over 300 laundry workshops and factories in North Kensington. Despite the long hours and hardship, many women were able to establish new modes of self and collective identity, as well as economic independence. The research was conducted via online archives and related literature; there is however, only one book on the subject, English Laundresses, A S0cial History 1850-1930, written by Patricia E. Malcolmson and a fine one at that. In addition, I interviewed Jenny Williams. She was one of many activists in North Kensington during the 1960s-70s who tried to prevent the demolition of the Silchester Road bath and wash house and was then involved in the running of a community laundry. This all culminated in the writing of five short scripts that were performed by Shelagh Farren, Nina Atesh, Rachele Fregonese, Rebecca Hanser, Mina Temple, Michelle Strutt and Rawleen Evelyn. The aim of the project was to bring a hidden story to light about women's labour and to explore its contemporary relevance for the #MeToo generation and the conflict over equality in our increasingly fragmented and polarised society. Washing dirty linen in public is a metaphor for social and artistic struggles that are needed to renew the body politic.

1840s map of North Kensington, showing the Hippodrome race course

Narrative overview of Washing Dirty Linen In Public 1800 Counters Creek is an ancient stream that runs from Kensal Green Cemetery into the River Thames. By the middle of the 19th century, the creek becomes an open sewer and is in the process of being culverted. Today it flows under the elevated Westway and down the middle of Freston Road. During extreme weather conditions it can flood to the surface and damage basement properties. 1850 The northern part of the parish of Kensington was still semi rural. The colony of pig farmers and brick workers that had originally settled here and were the focus of public health interventions, are in decline. People, dogs, pigs and poultry all lived together in poor housing. There was no church or school in the area. With men out-of-work, women establish a cottage industry taking in washing from an expanding upper middle-class. This became the dominant form of women’s labour in Notting Dale. 1851 Census: Jane - wife, head of the family, mangling woman John - husband, turns my mangle 1860 Laundresses used manufactured soap that was dissolved in water to form a jelly. Notting Dale was one of the few places in England where local soap was made. It used recycled raw materials from the pig farms and brick works. Food refuse was collected from the well-off houses and boiled down to make fat and this was combined with ash from the brick making industry to make the soap.

Performances by Shelagh Farren and Nina Atesh at Waynflete Square on Silchester Estate

And the SPACE (Supporting People And Community Empowerment), 214 Freston Road 1862 Performance in Waynflete Square on guided walk: Shelagh Farren as Irish migrant, Kathleen Doherty. "I’ve done eight hours solid bent over that wash-tub. The skin on my hands is all raw. Mrs Peters will do all the ironing, thanks be to god. Good luck to her with them frilly shirts. Gowns in fancy colours. And those blooming bloomers! Someone’s got a right royal arse. They belong to them rich people down Notting Hill Gate. They like to buy the best from Paris. I can read you know! Well, a few words on them labels. They want nothing but the best and when they’re soiled, they want it cleaning. And they expects the likes of us to do it for a pittance." 1862 Third Mother’s meeting held in the drying room of a laundry in Latimer Road. 1862 The opening of Latimer Road Mission as the first community building in Notting Dale. It offered a pioneering creche facility for the laundresses who worked in the area. The Latymer Community Church is the direct descendant of the original mission.

Latymer Christian Fellowship Trust (formerly The Latymer Road Mission)

Leaflet celebrating 150 years of loving and serving the community, 1863 – 2013

1870 There is a growing urbanisation and industrial expansion of laundries. The working conditions in workshops are unhealthy, with long hours (10-18 hours a day are the norm) and poor pay. But new found economic status for working-class women as the bread winner. 1880 Laundresses had a reputation for hard working followed by drinking and brawling. Pubs in Notting Dale were open on a Sunday in defiance of licensing laws. There were often more women to be found in pubs then men. Laundresses could be paid by beer that was consumed on the job. Theft and crime from the laundry industry was rife. Many laundresses saw an opportunity to abscond with linen and clothes.

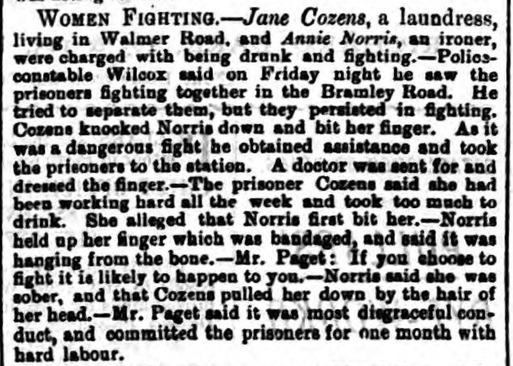

West London Observer, 1884 and 1892

Newspaper image © Successor copyright holder unknown. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive ww.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

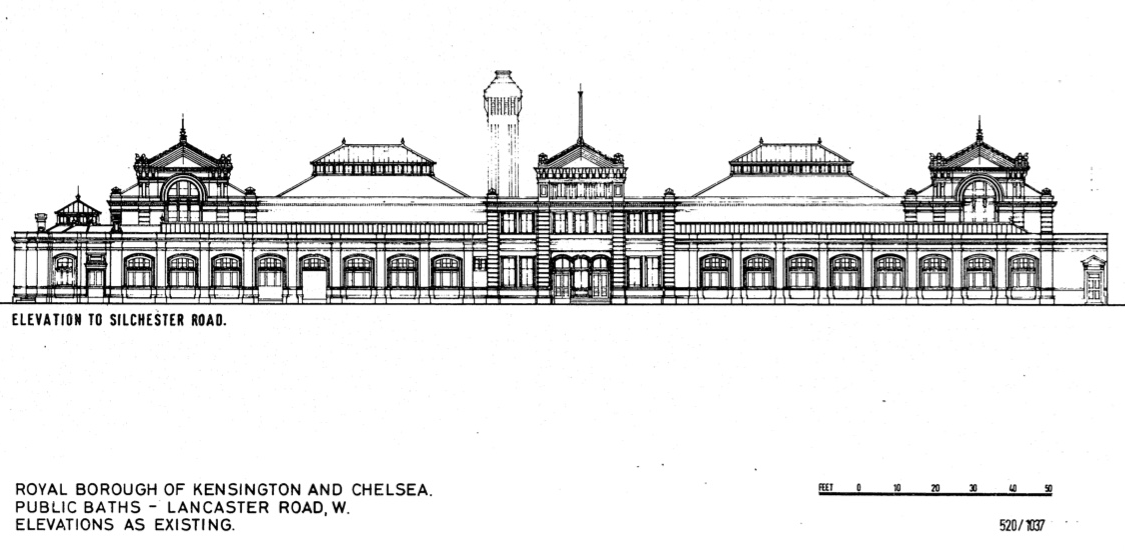

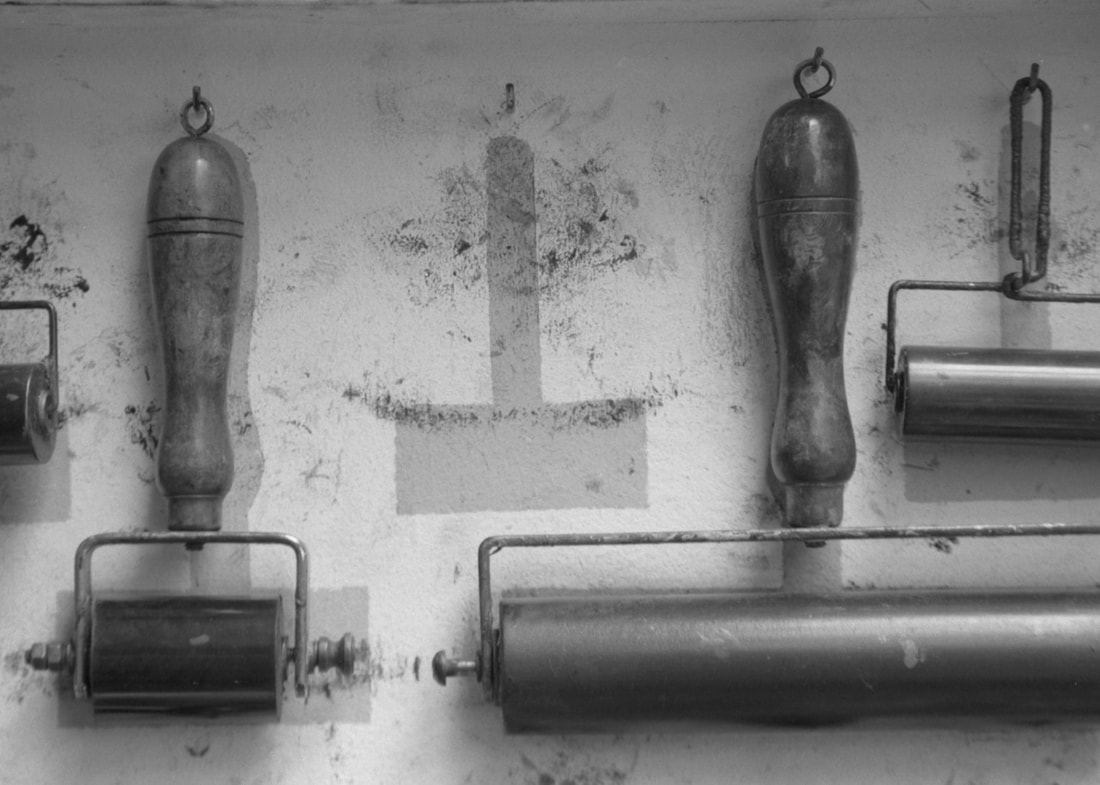

1885 Harrow Mission Church opens on Latimer Road and is converted into the Harrow Club in 1969. It is a Grade 2 Listed building. 1888 Opening of Silchester Road Baths & Wash House at a cost of £51,168 (today £6.5 million). There were 3 swimming pools and 74 baths classed for use. The water from the 1st class baths was recycled and used by those in the 3rd class baths. The public laundry had 60 separate washing compartments. 1890 Washers could earn as little as 2 shillings and 6 pence for 12 hours a day (with breaks). Ironers earned 3 shillings and 6 pence. 3s 6d = £15 in today’s money. 1890 Performance in The SPACE by Nina Atesh as Florence Smith, 16 year old laundress. Supported by Shelagh Farren and Mina Temple. "We’ve been working about four hours solid without a break. But it’s better to be here than at home.... or at school. They treat me like a child. But I’m the first in the family to earn a proper wage. And here I can make six shillings a week. I have to give half to mother mind. But the other...... half..... well it goes in the....piggy bank. And I hide that under the floorboard. Otherwise father will drink it all up." 1890s Sayings and thoughts of women (and men) in Notting Dale: “A shilling you earn is worth two given you by a man!” Men: “To marry an ironer is as good as a fortune.” Women: “The best ironer gets the worst husband.” To wash on a Monday is to be virtuous. But who washes on Friday is half a slut; And who that washes on a Saturday is a slut to the bone. The washing week: Collection and sorting on a Monday, Marking, soaking, washing and mangling on a Tuesday Wednesday is ironing and airing Thursday is folding and packing And Friday is delivery of the snow white linen.

1888 Kensington Directory

1890 Amalgamated Society of Laundresses and Working Women is established and campaigns for better safety and wages. However small laundries run by women fear going out of business if their work is regulated by the Factory Acts. 1890 Estimated 200,000 attend a Labour Demonstration at Hyde Park including the Amalgamated Society of Laundresses. 1890s 249 laundry workshops and 58 laundry factories registered with Kensington Council’s Medical Officer of Health. 1893 First woman factory inspector to be employed in London is appointed by Kensington authorities. Miss De Chaumont, Inspector of Workshops, will visit over 200 laundry workshops in North Kensington during 1907. 1913 Sylvia Pankhurst, suffragette campaigner, addresses a meeting for women at the Silchester Road and Bath House.

Narrative storyboard of the North Kensington Women's Welfare Centre, 1924-74

The third birth control clinic opened in England by Margery Spring Rice and friends.

1924 Performance in the SwimFarm under the Westway by Rachele Fregonese and Rachel Hauser. Margery Spring-Rice has just opened a birth control clinic for working-class women on Telford Road and encourages her depressed cleaner, Freda, to pay a visit. Freda: I wish I knew about those things before I got married. Margery: It’s easy to learn. There are a few methods and we need to find what suits each woman. In most cases, that will be the use of a cervical cap. It is really simple to use when you get the hang of it. I don’t think Mrs Jenkins or even the daughter for that matter, fully understood what we were talking about. She then got angry and shut the door on us. After that we heard her throwing out their...what is it....food waste...hopefully nothing more. Out of the window and down into the yard. It nearly fell on someone’s head. Freda: I spose, she’ll be wanting to throw out her daughter now. Margery: Hopefully not out of the window. 1934 West London Observer: “During the sale of the effects of a German laundress who died from hunger recently at the age of 80, a diamond of superb quality valued at over £3000 was found in the pocket of an old bodice she used to wear.”

Photo display at Latymer Community Church.

Mrs Joan Hales doing her Monday wash, circa 1946. Reproduced from Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. 1945 Performance at Latymer Community Church by Mina Temple. Victory in Europe Day and Joan Stewart, with a heavy heart, goes on her weekly visit to the wash house. Joan: I wonder who’s washing today when the whole of London is celebrating the end of the war? I knew it! Only us old timers. Hilda and Nessie and the others. They’ve had their tea and sarnies. What a racket! Just listen to their false teeth. Ah. Here’s a space for me, right at the end, where it’s a bit quiet. I can see them looking at me, wondering what I’m doing over here. Silly cows! Don’t they know it’s my Wednesday wash! 1960 Kensington Post: Flood Havoc in Notting Hill for 60 homes as families wade waist-deep in sewer water.

Cinema Poster: Leo The Last

Orange sequence shows the revolution moving from the laundry to the street.

1969

The film, Leo the Last, is made on Testerton Street just prior to its redevelopment into Lancaster West Estate. In the penultimate scene, an aristocrat, played by Marcello Mastroianni, incites women at the bath house to join the revolution against poverty and housing. 1970 Performance at Latymer Community Church by Rawlene Evelyn and Michelle Strutt. Grace Augustine is visited by her sister, Jackie, in a slum house on Testerton Street. Jackie: And why the wall all damp under these cracks? Grace: I was gonna hang up a few posters. Beaches and sunsets. They add colour to these grey walls. Jackie: You cann add colour to this slum. Me no joke. You no notice round here, how all the houses painted black. Grace: It’s for the film. Jackie: It like you live in fantasy world round here. 1974 The North Kensington family planning clinic closes down on Telford Road. The land is being redeveloped and contraceptive services are finally being taken over by the NHS.

Local resident's comment at the exhibition Q&A:

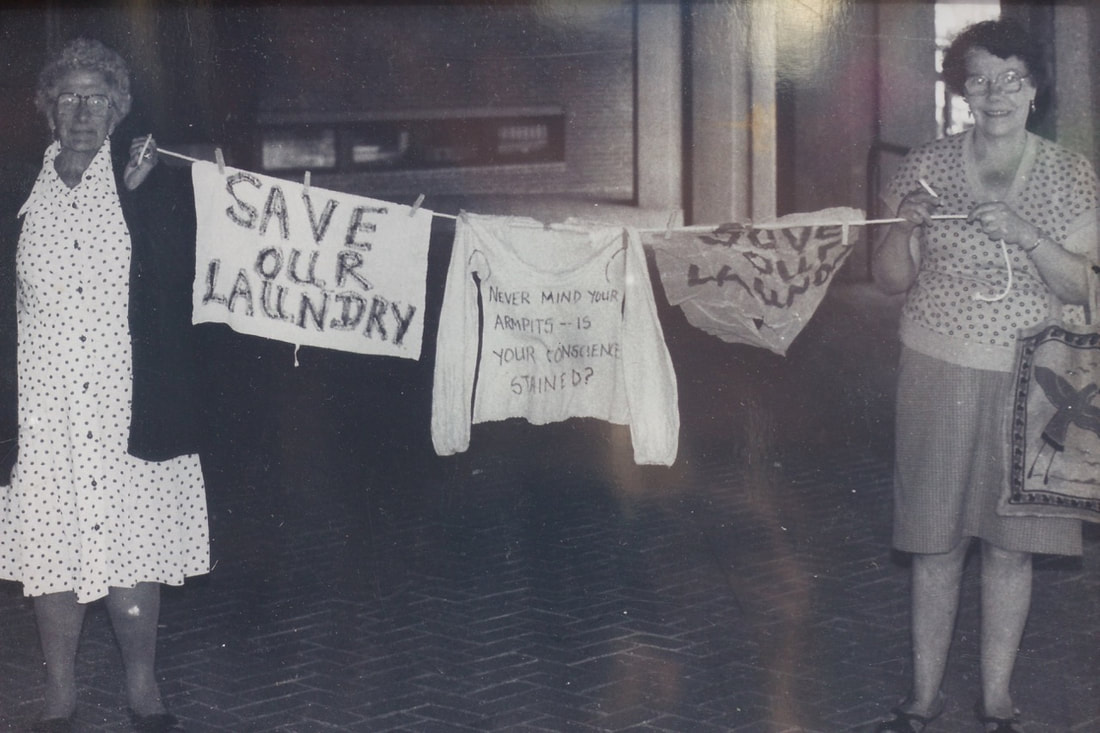

"I was there as a teenager. We had a big picture of a bra and it said. How can we wear our bras if we have nowhere to wash them?"

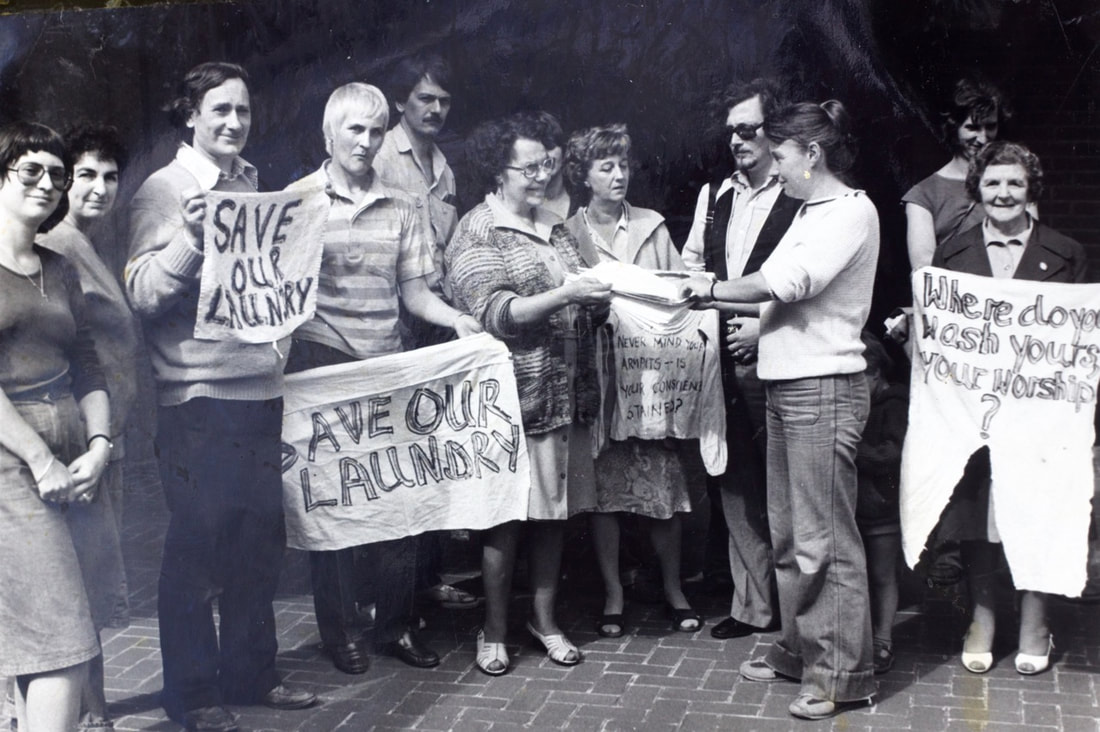

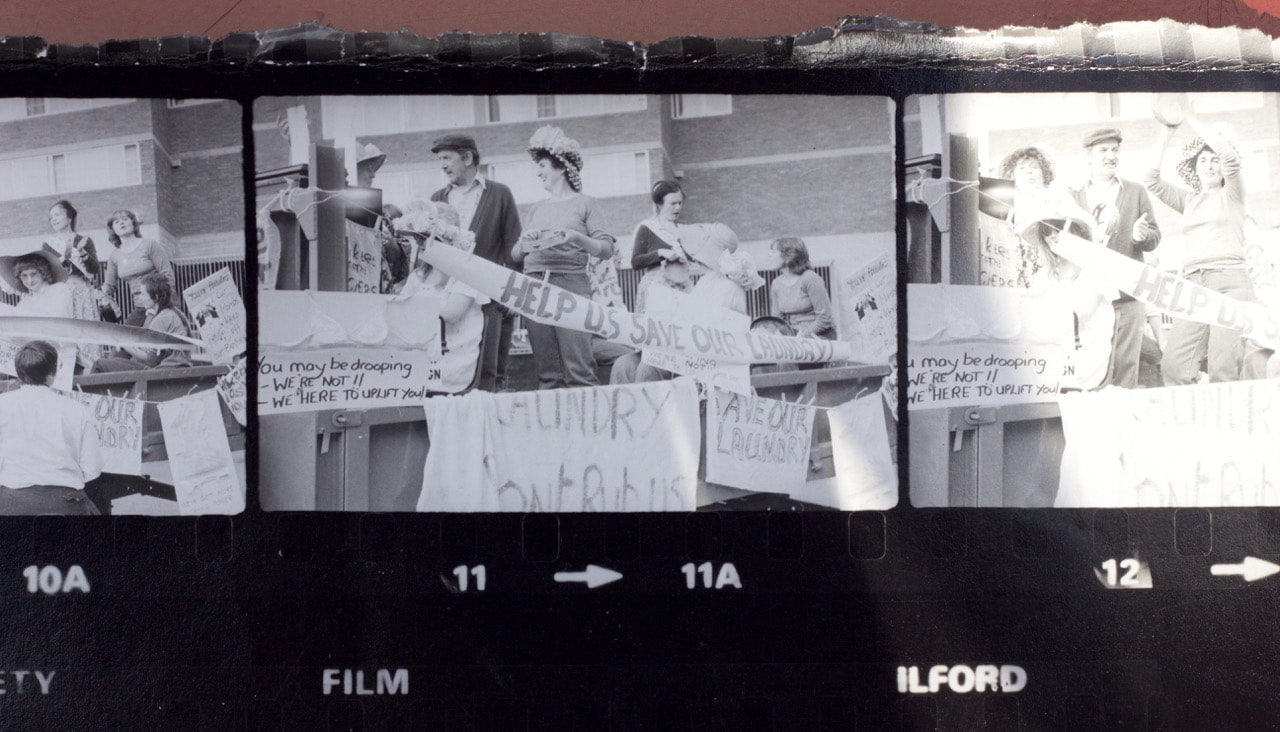

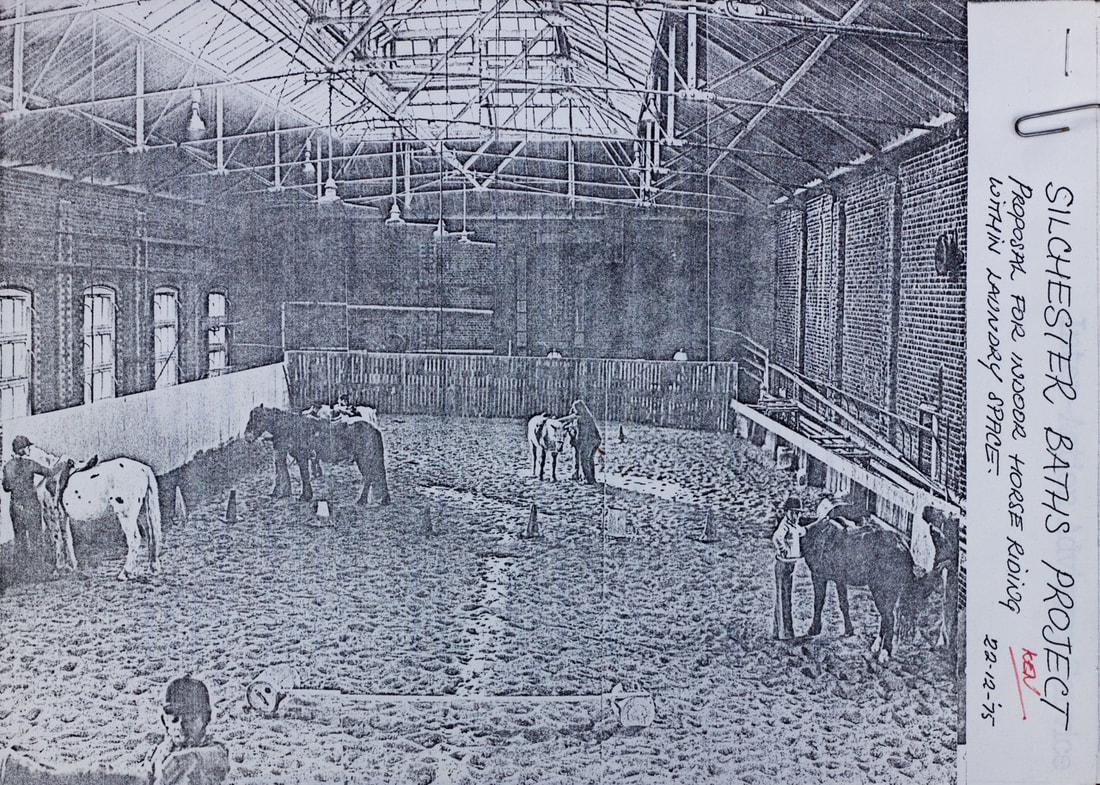

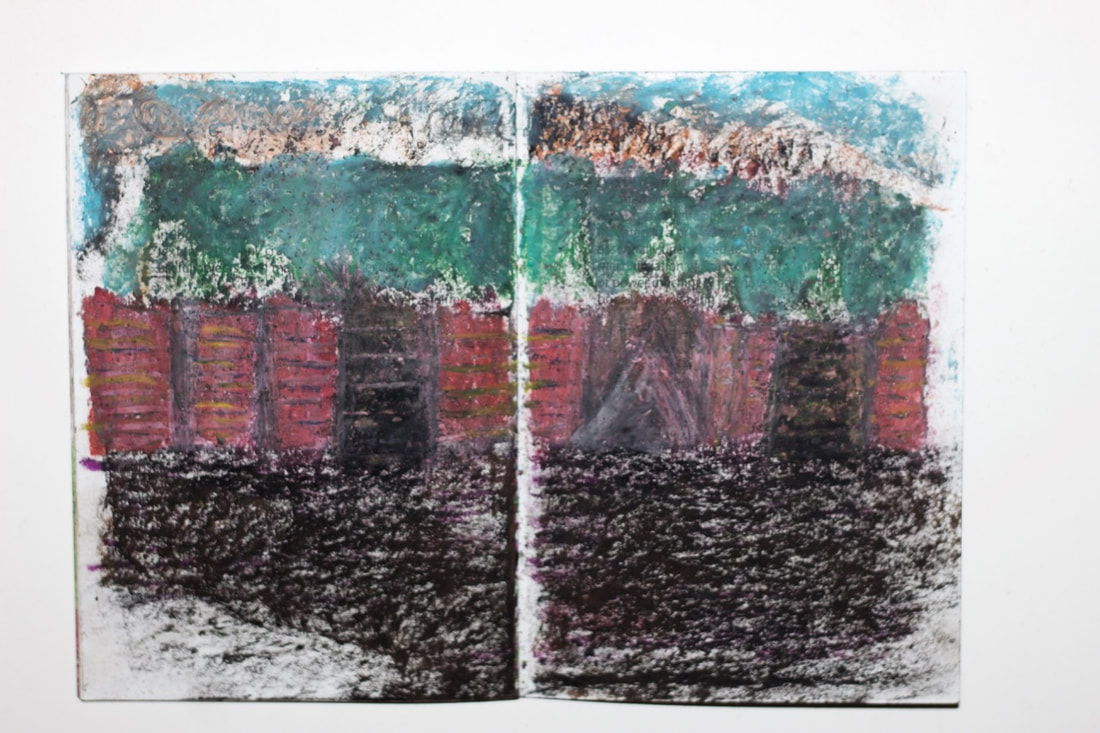

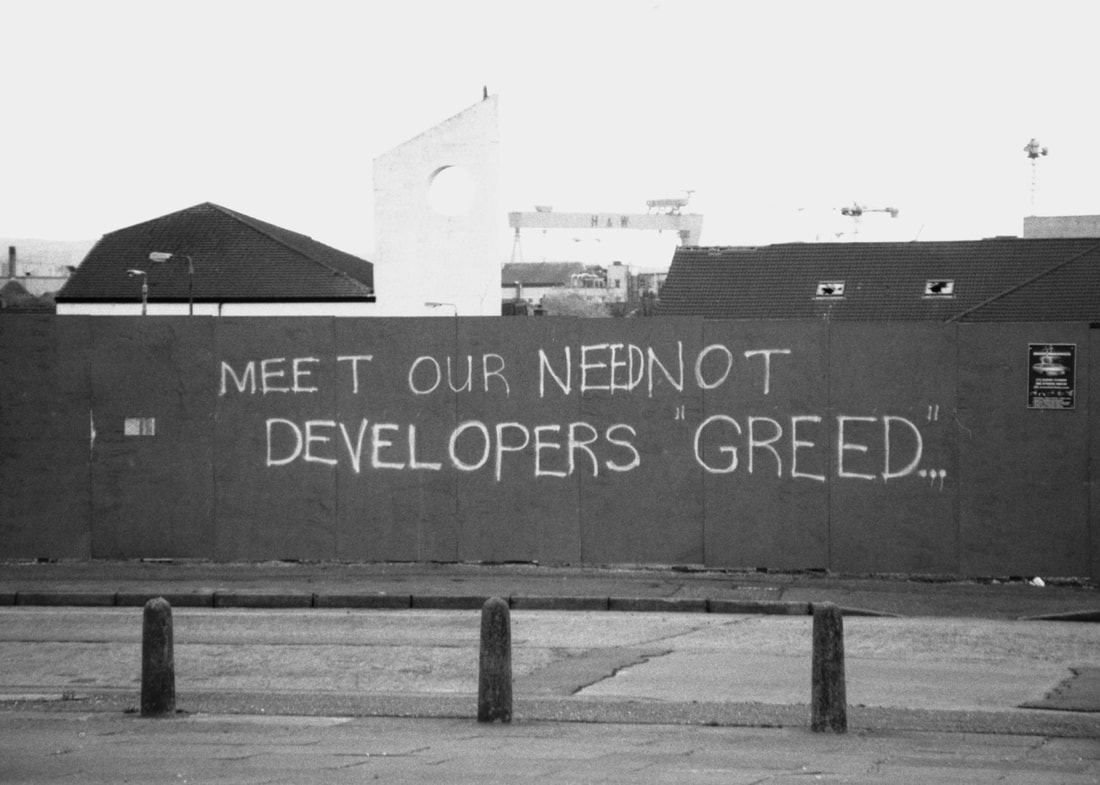

1974 The closure of the Silchester Road Bath and Wash House as part of the Lancaster West estate redevelopment. Women campaign to save the building and its laundry facilities. 1975 The council open a laundry under the Westway and after more campaigning, local women, take over the running of the laundry. 1980’s Demolition of the Bath and Road House and closure of the Westway Laundry. 2013 The last of the large family-run laundries, White Knight Laundries, closes its North Kensington branch with the loss of 75 jobs. It had been providing domestic and commercial services since 1933.

Notting Barns as framed by the Westway flyover and the Circle and Hammersmith and City Railway.

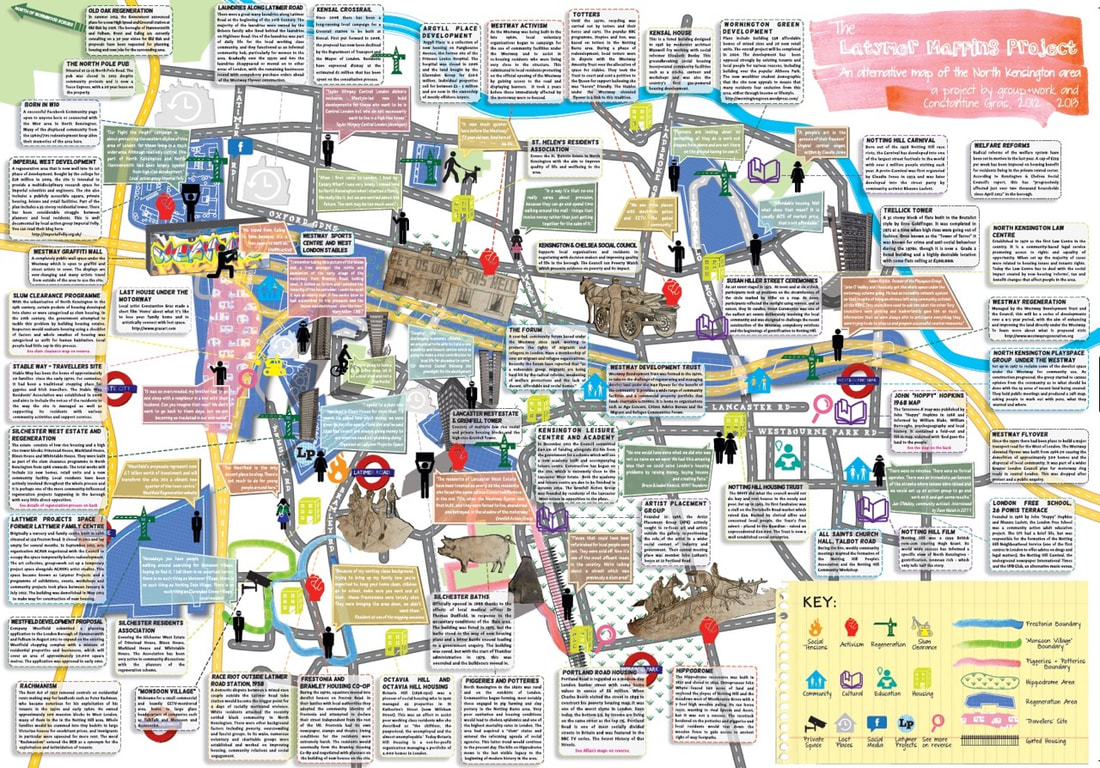

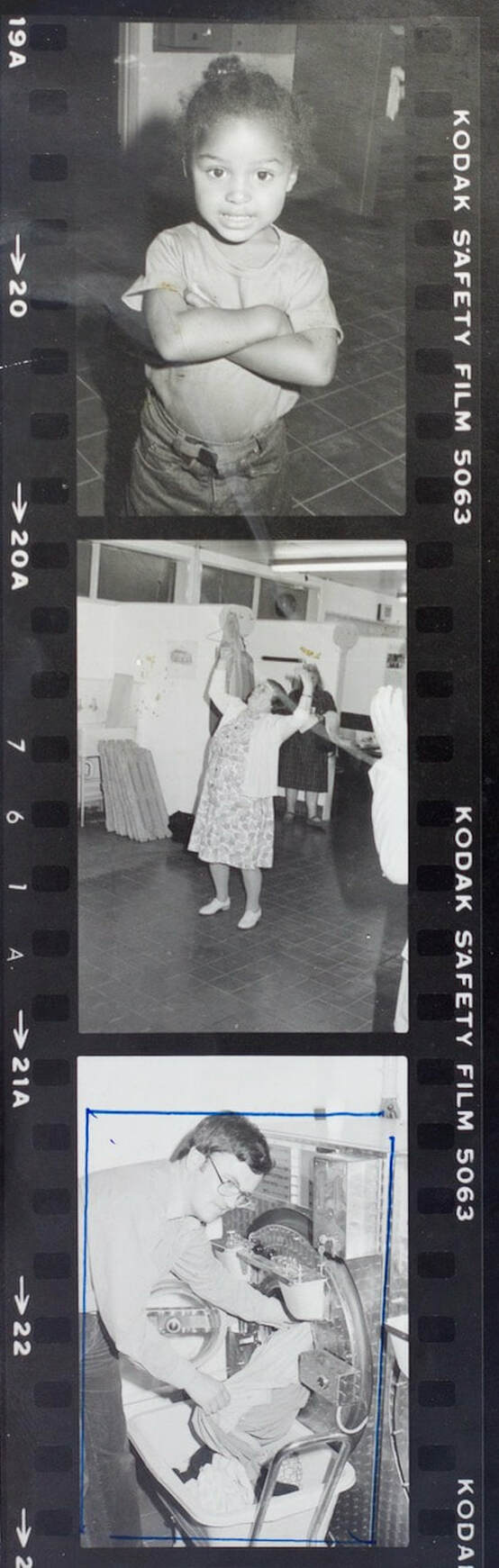

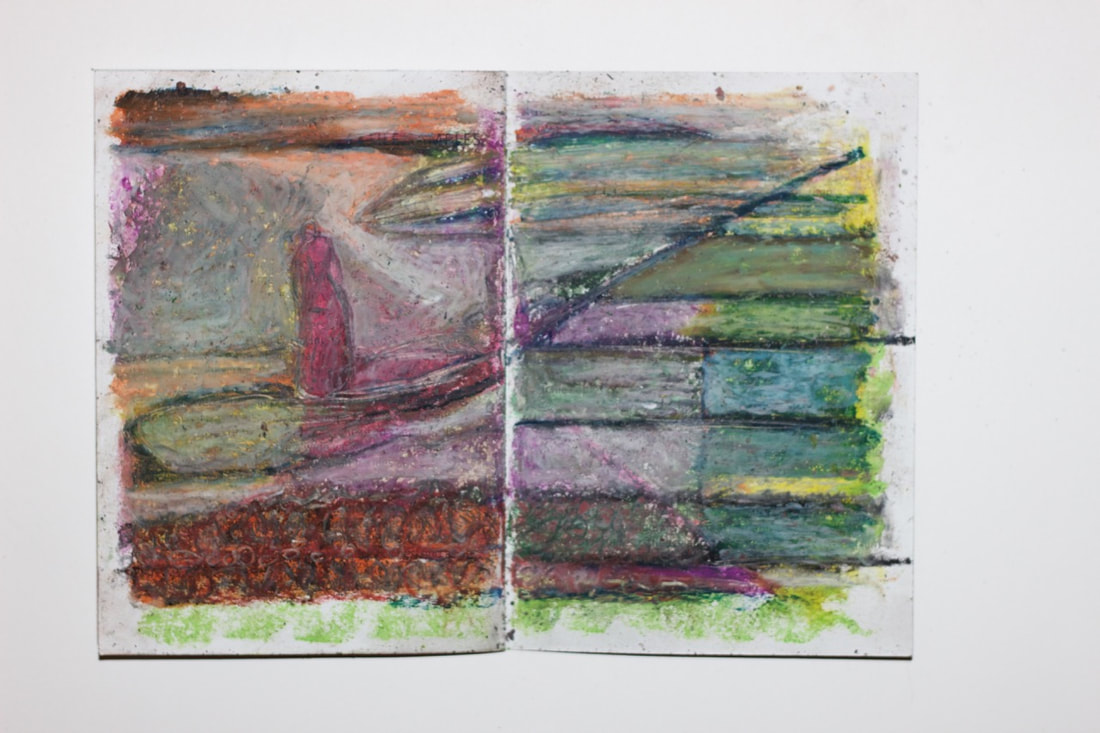

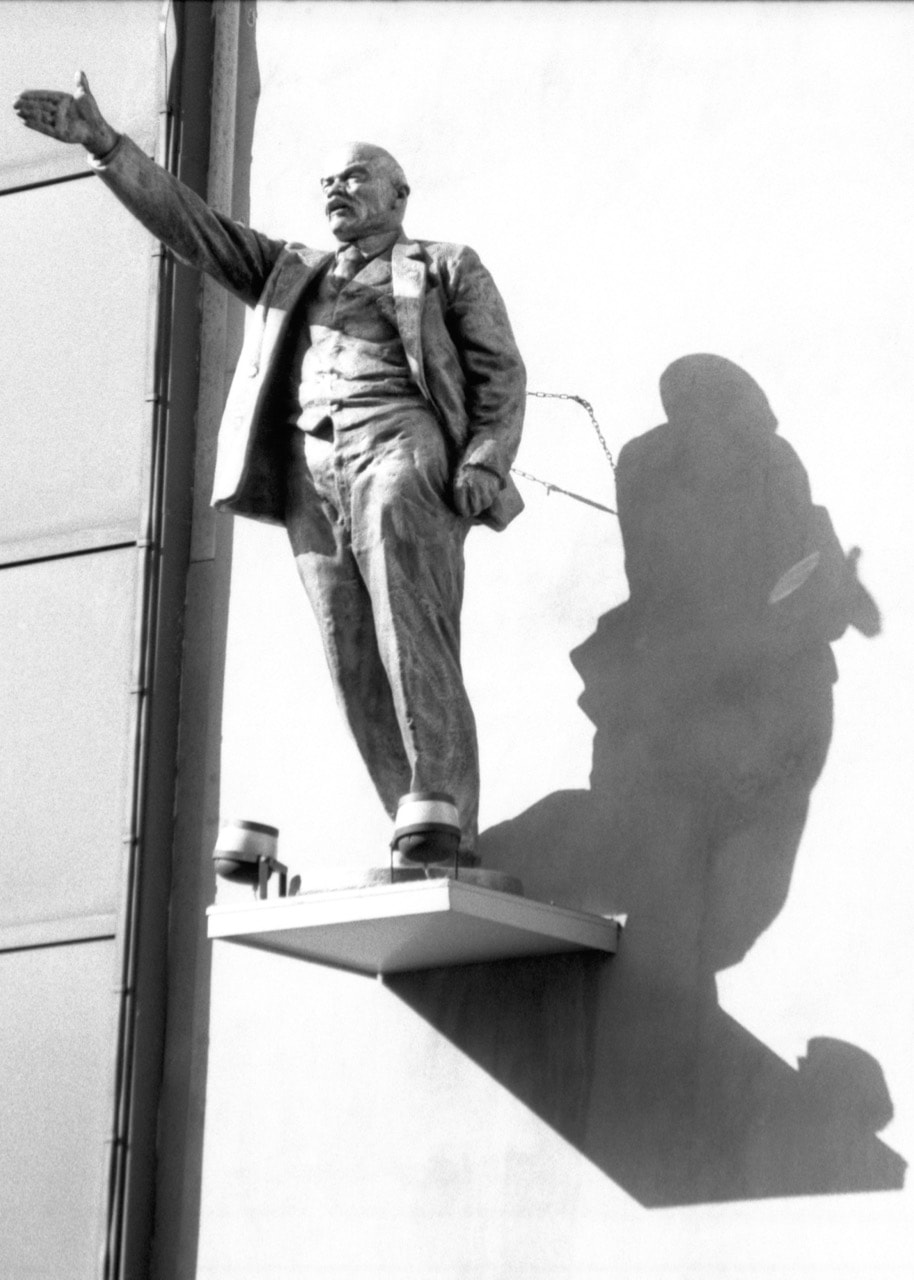

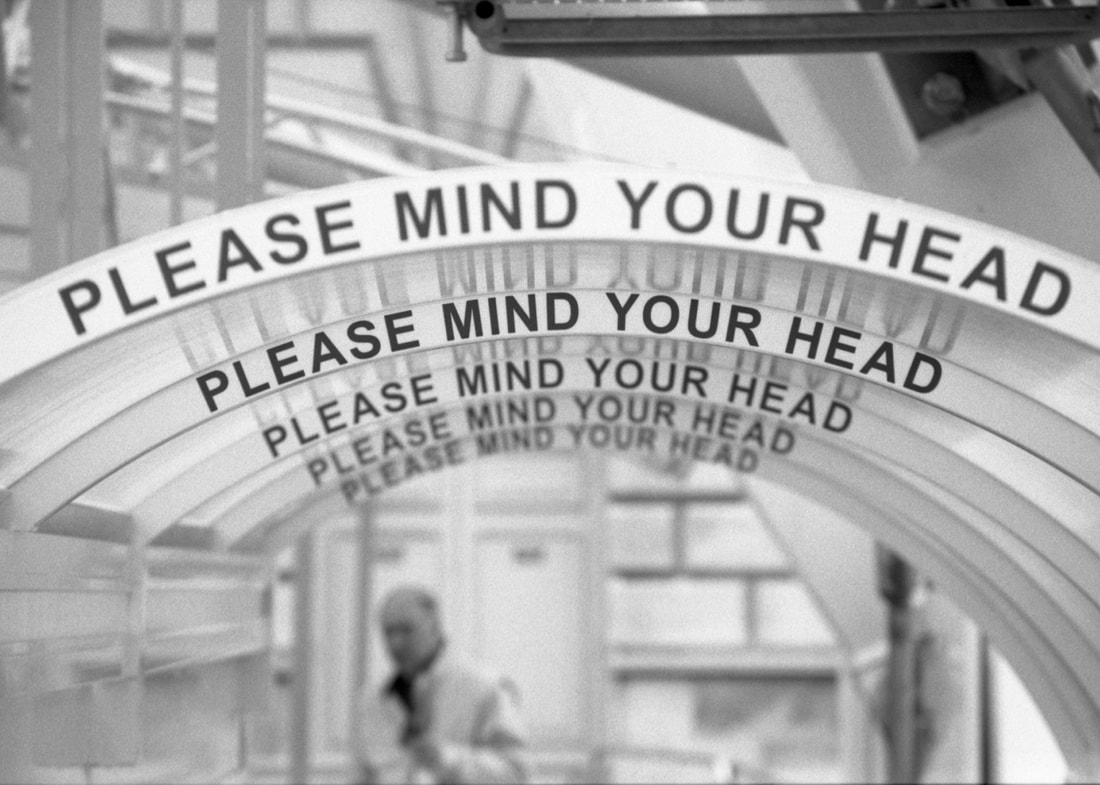

The four tower blocks of Silchester Estate and Grenfell Tower at Lancaster West Estate. Photo early 1970s, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Archives Our guided walk and performance navigated around railway lines, across Silchester estate and under the Westway. At the launch of the Power Plant exhibition at the Serpentine, Hito Steyerl outlined her visionary art that connects technology with the discourse of power; she also addressed the (Sackler) elephant in the room. For me, I've got more of a swine complex. One that oink oinks in North Kensington. The roots of our land here are connected with pig farms (and potteries) and these gave rise to the first of many public health issues. The Victorian authorities prohibited this form of labour in the 1860s. This is the point at which my current art project, Washing Dirty Linen in Public, that was developed as part of Hito's exhibition, comes into play. As that land was being urbanised, laundresses and industrial laundry work, took root. This was later connected with the building of the Silchester Road bath and wash house that had extensive cheap laundry facilities. These female-centred modes of work lasted until the 1970s with the building of the estates (with hot water, baths and central heating!) and the advent of consumer appliances that minimised the need for laundries; the so-called sexual revolution also freed women to enter the wider workforce and not be tied to the demands of large families. All these historical elements are being woven together for an exhibition and guided walk on 27th April 2019 at Latymer Community Church. My collaborators, actresses from the People's Company, have been bringing historical scripts to life drawing on their own memories of parents and distant ancestors from Ireland to the West Indies. We are thinking about how washing is being exploited in today's society with domestic home workers and in the hand car wash industry. In the background of our project is #MeToo and the recent Gender Pay legislation for companies. This liquid history is ripe for creative reinterpretation and has a contemporary resonance. Landscape for Colin MacInnes: "Out of this road, like horrible tits dangling from a lean old sow, there hang a whole festoon of what I think must really be the sinisterest highways in our city...." (Text from Absolute Beginners describing the streets of Notting Dale, 1958) oil pastels, 16x20, 2012 High Rise living with ceramic creature comforts Oil pastel, 16x20, 2012 Top photo: Shelagh Farren at the Westway graffiti wall. She will be playing the role of Kathleen Doherty, laundress in 1860. "Pat doesn't like me working, but I'm not going out begging like some tinker and I've seen what it's like in the workhouse. If I have to, I will wash all the clothes in the Dale to put food on the table and pay the rent." Bottom photo: Rawleen Evelyn as Grace Augustine, resident of basement flat at Testerton Road in 1969: "The council change everything round here. One day a house is here. The next day, gone. But maybe the bath house will survive." Washing Dirty Linen in Public A performance based walk and exhibition about women's labour and activism in Notting Dale Saturday 27th April at Latymer Community Church, 116 Bramley Road Exhibition display of archive images, drawings and short films from 11am - 5pm Performances also taking place at the church hall throughout the day Guided walks at 10am and 2pm, booking via Eventbrite Walks sold out - please contact us to be added to reserve list Commissioned as part of Hito Steyrl's exhibition at the Serpentine, 11 April - 6 May 2019. When I was visited by Hito Steyerl and staff from the Serpentine Gallery last year, I took them for a walk around the streets of Notting Dale. I explained how housing issues and community activism were captured in a map made during the Latymer Mapping project. Fast forward a year, Hito was preparing for an exhibition at the Serpentine and kindly asked me to recreate the dynamics of the map as a walk. I didn't want to revisit the politics of housing. I thought about using lost or forgotten spaces. Counters Creek that is buried under the streets. A cinematic narrative of historical voices. Each coming together to shed light on contemporary issues; but I needed a focal point. One detail on our original map highlighted the history of laundries in the area. At its peak, there were over 300 workshops and factories in North Kensington supplying cleaning services to the working class households and their more affluent neighbours, as well as hotels and restaurants. As I dipped my toes into the research, the idea formed of connecting the first laundresses of the 1860s with the Silchester Road and Bath House that was built in 1888; and then relating these to the post-war slums and the building of the social housing estates. I envisaged a series of working-class women characters, including recent migrants, who created and then carried on a tradition of women's labour. Many of the original businesses were family run, perhaps with a woman at the helm. Washing could be a capital business and the advent of steam powered machinery was rapidly employed to maximise profit. For the laundresses the work was hard and poorly paid, but could be relied upon at times when extra income was needed for the household. The gathering together of women in this mode of labour created a new social dynamic inside and outside of the home. Becoming an ironer of silk was one of the more specialised roles that entailed better wages. There was a local saying that men of a certain temperament flocked to the area in the hope of marrying and being kept by an ironer. In the archive, there are also early examples of women organising themselves into unions that wanted to improve the working conditions for laundresses that were not fully regulated by the Factory Acts. And also accounts of laundresses taking part in the large labour demonstrations of the 1890s, travelling on a processional float to Hyde Park and getting joyously pissed, dancing and singing, effing and blinding. From this schematic outline, I penned the following characters and they will be performed during the guided walk and at the exhibition on the 27 April: Kathleen Doherty is a migrant from the Irish Famine, who, for a pittance, washes the clothes of the prosperous class in Notting Hill. Looking across the open fields of Notting Dale, she has a comical vision of the future. Florence Smith, 16 years old, already a veteran of the steam laundry workshops, contemplates her adult life as a silk ironer. Freda Palmer is the charwoman who befriends her employer, Margery Spring-Rice and contemplates visiting a birth control clinic that has just opened. Joan Stewart sets off for her weekly visit to wash clothes at the Silchester Road Bath's. It’s no ordinary day: the country celebrates victory in Europe while Joan contemplates the fate of her family. Grace Augustine is a West Indian mum, living in a damp, unfurnished flat, on a road that is about to be demolished for the building of Lancaster West estate. She is visited by her sister Jackie and both are forced to seek sanctuary at the bath and wash house. The monologues and dramatic sketches will be performed by Nina Atesh, Rawleen Evelyn, Shelagh Farren, Rachele Fregonese, Rebecca Hanser, Michelle Strutt and Mina Temple. It was a pleasure to meet up recently with Jenny Williams who told me about her involvement in the laundry narrative. She was raised in North Kensington, worked for the Greater London Council's Women’s Committee and managed children’s services for Lambeth and Camden. She became involved in many of the local community campaigns from the 1960s-80s that addressed the chronic lack of child care facilities and play spaces. As we will discover in the following interview, there are strong parallels between the 1890s laundresses and their 1970s counterparts who saw their beloved Victorian bath and wash house demolished for redevelopment. As a result of effective campaigning, the women were able to get RBKC council to open a new laundry under the Westway. The unglamorous world of soap and suds was the setting for dissent and collective solidarity at a time of profound social change, especially for the elder residents of the community. One of our battles in the 1970s was to try and save the Silchester Road baths and wash house. It was really well used. Mothers who had large families, tended to load up their prams and go to the wash house. You took everything in a great pile and when you came out it was all folded, ironed and you pushed it home. You had your time and day for going. You could be there for three hours and it was very cheap. While you waited, you could buy tea and coffee and bacon rolls. There was a real community aspect to it. That was why there was such an outcry about it. We’re talking about people who had practically been going there all their lives and suddenly the council wanted to close it down. It wasn’t just about losing the laundry. The building had 3 swimming pools at one time: a ladies pool, a gentleman’s pool and a public pool. There were also individual baths and a medical baths centre. When the council announced the closure in 1974, for the continuation of the Lancaster West development, the local women were furious. So it wasn’t difficult to get their support. We even had Max Hastings come to one of our laundry meetings and he wrote an article in the Evening Standard. There were meetings with Cllr. Middleton who I believe was chair of Libraries and Amenities at the time. He said it was rather like Livingstone meeting the savages. We didn’t take very kindly to that sort of remark. The local MP, Sir Brandon Rhys-Williams, was very supportive considering he was a Tory. Also the dust men and Tony Sweeney, the trade union shop steward. I know it wasn’t terribly appropriate, but we got hold of a lorry and took part in the Carnival. That’s me in the middle with the large hat on! Alongside the campaign for retaining a laundry, we got a preservation order on the baths building. Mainly because it was designed by architect Thomas Verity who didn’t usually do municipal buildings. Also it was a nice building. Then various other people got interested in it and put forward these different proposals about how it could be used, including putting a stables in there. Our view was that it should be a community centre and there should be different facilities including a covered market. Then we went to a public inquiry. But the council won in the end. It was pulled down. The council were struggling to get their head around what was happening. Our campaign was just part of a lot of community activism taking place in North Kensington. And we kept telling them we didn’t want a laundrette, we wanted a laundry! The council finally agreed. After the baths closed, they built us a new laundry under the Westway, right next to the Maxilla nursery centre. So we had our laundry which lasted about 5 years. Then in 1980, the council again decided to close it down, So we had another campaign and what the council did was classic. They said to us, why don't you run it! They hand things over, so as not to have anything more to do with it. So we set up a laundry company. Residents wanted to continue to have sinks that they could wash things in and to have access to irons. This service lasted for another 9 years until the machinery started to break down and became too expensive to repair. To be fair to the council, they had actually put in very good quality Miele machines. At this point, the Greater London Council Industry and Employment Committee gave us a grant and we put in a brand new laundry. It was a steam laundry and we had to have a rota of women who managed the boiler. The new laundry was opened by Mike Ward who was the chair of Industry and Employment at the GLC. We told him to bring in his washing for the opening. They supplied us with very expensive machines, the cost for the washer extractor was £5,980 for ten which was a lot of money in those days. Good old GLC! We even had heat exchangers put on top of the dryers, so it was quite economical. The GLC were very interested in green projects. It really was a super service. That lasted for another 5 or 6 years, until again, the laundry machinery broke down. And it was also the time when residents stopped using the service. So our laundry campaign and business started in 1974 and went on into the late 1980s. A lot of us spent many years looking after the laundry, as well as doing other things in the community. Photographs kindly reproduced by Jenny Williams ©

Come, my dear referendum Go deadly cat > apps < bleed the VHS signal The night I buried my passport (in 1973) A suitcase for the deal Euro sting in the Scorpion's Tail The torture of Article 50 What have you done to Therese's voice? Whiplash for the body politic The killer rubber dub (out of sync) Brexit - My Giallo 10.5 x 15cm, oil pastels and pencil 2019 (going on 1973)

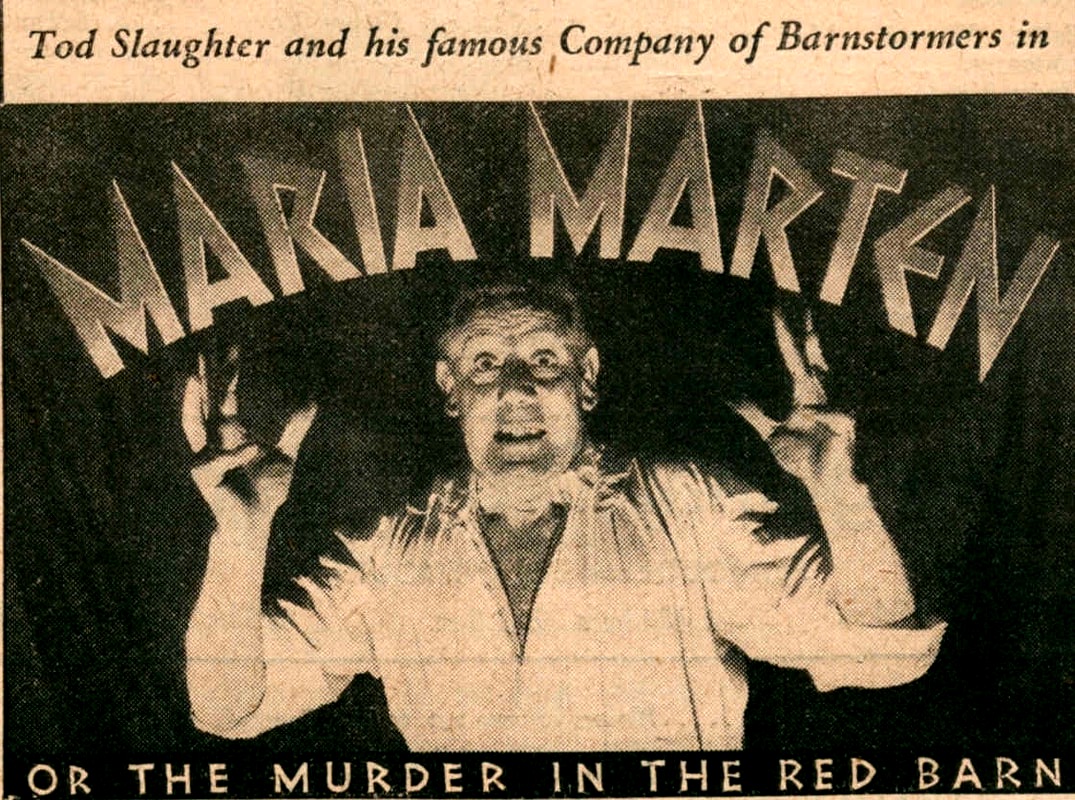

Reproduced from Radio Times, 2 November 1934 / BBC Genome

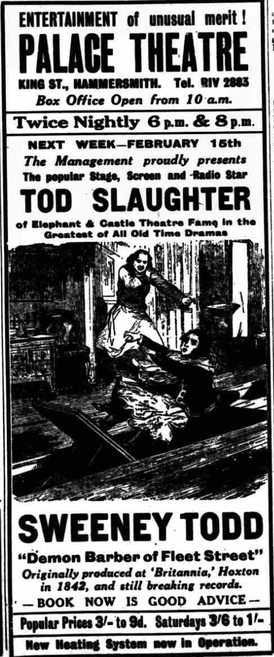

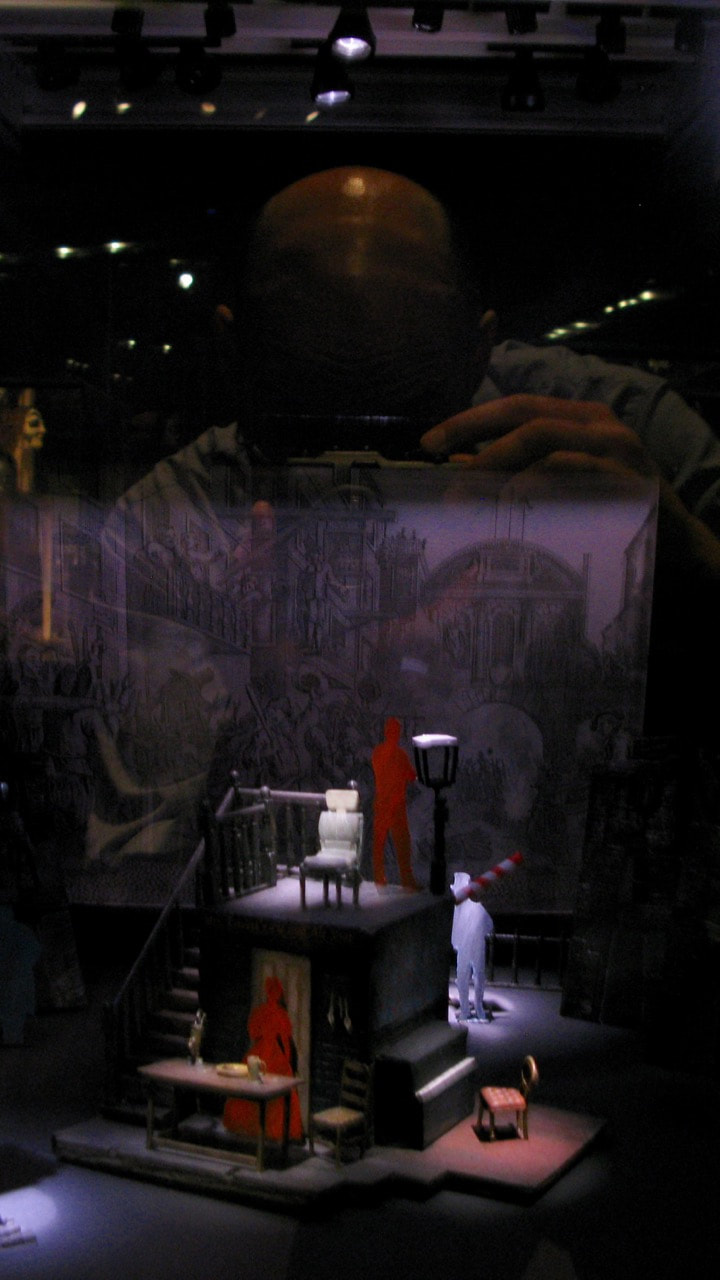

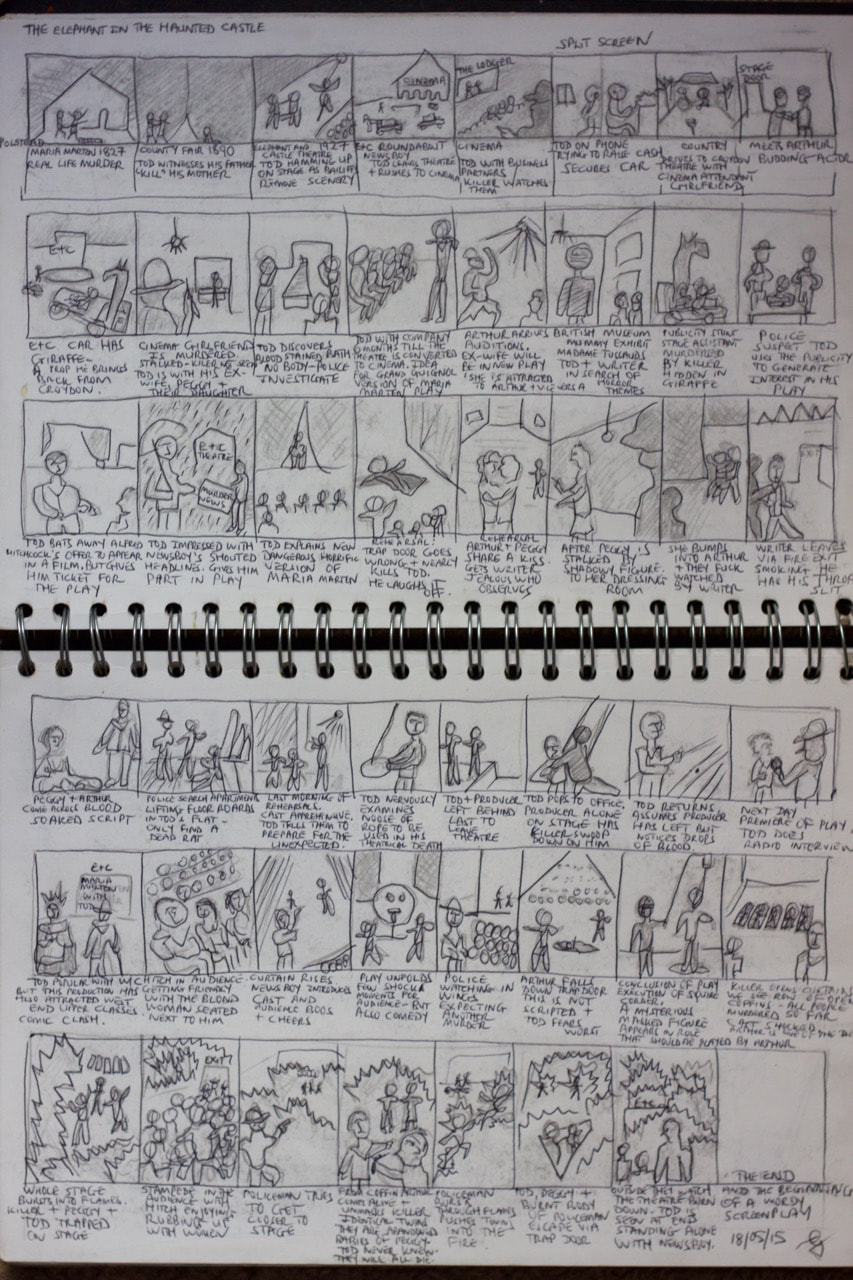

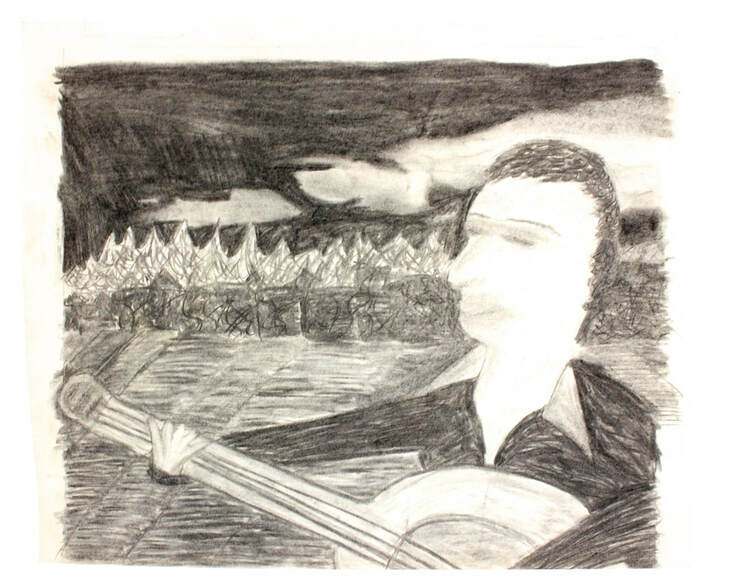

The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle was made in collaboration with John Whelan and People's Company. It told the dramatic story of the Coronet as theatre, cinema and night-club. The project had a curious genesis. It started in 2012, when I tried to remember a film I had seen as a 14 year old, a horror film screened at theABC Edgware Road. The film with its visceral supernatural murders, inspired by Dario Argento's influential shocker, Suspiria, made a deep impression on me at the time. However, over time, I completely forgot what the film was called; while still being able to vaguely recall certain scenes. Decades later, I tracked down the film at Westminster Archives, looking through back copies of newspaper listings. The recovery of that memory as a film called Terror (1978, released in 1981), emboldened me to artistically connect with the lost cinematic spaces and experiences of my youth. My Terror ABC had long been demolished. But I discovered the Coronet in the Elephant and Castle was once an ABC cinema and was being threatened with closure. This was a perfect opportunity to explore my love affair with cinema. The Melodramatic Elephant art project was initially framed around the actor-manager Tod Slaughter, noted as one of the greatest (and greatly under-appreciated) stars of melodrama. He provided a more obvious link to my interests; the intersections where theatre and film, horror and melodrama, meet and diverge. However, I deviated from this focal point when I unearthed the poignant story and medical records of Victorian actress, Marie Henderson. Her life and death, were so poetically linked to the Coronet and her ghostly presence in the building was a perfect medium for threading time across the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. She was also a completely unknown story, while Tod Slaughter was already a minor footnote in film history. I handed over these schematics to John and the People's Company and they created a spectacular last-ever theatrical event for the Coronet. This blog will provide some context to the original ideas for the project and a sample of art work that was generated. In the process, we doff our cap, to the achievements of Tod Slaughter's 50-year career across theatre and film, radio and television. He seemed to be born with melodrama in the blood and was still performing it with relish and abandon, when he died of coronary thrombosis in 1956. Tod had an-end-of-career swan song, impressing the critics and a new generation unfamiliar with the creaky trappings of stage melodrama. A short performance on BBC TV, prompted over 3000 letters asking where Tod's plays could be seen. They recognised the sincerity of his quaint performance in an era that was shifting gears from the Method to the Kitchen Sink. I want to also track-back to Tod's theatrical heyday. We can pin this down to the year, 1927; the last of his three-year tenure as actor-manager of the Elephant and Castle Theatre. He mounted what should have been a routine production of Maria Marten, scheduled to last for one week. Maria Marten or the Murder in the Red Barn was well known to Victorian theatrical audiences and was based on a sensational real-life murder, trial and execution that occurred in Polstead, Suffolk, in 1827-28. Tod's production became one of the hits of the season and was seen by over 100,00o people across 115 nights. The West End audience flocked south of the Thames to witness this old-time drama being presented in a fresh way. I particularly like the reviews that describe the audience: a mixture of the local Southwark working-class, eating oranges and drinking stout, boisterous in their interaction with the performers; while seated cheek-by-jowl, with the mannered ladies and gents, using viewing glasses to scrutinise the on and off-stage shenanigans. You can imagine a humorous culture clash. This was a moment of significance: melodrama being resurrected in a theatre that was on the brink of conversion to a cinema. All this research was percolating in my mind, unlocking a range of cinematic ideas and storyboarding.

The West London Observer, 1943

Newspaper image © Successor copyright holder unknown. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk Set model box for Sweeney Todd, 1993 V&A Museum

Sketch 1 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod watching Hitchcock's The Lodger (1927) while being stalked by a serial killer 22 x 30 inches, Oil pastels, 2013

Sketch 2 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod as William Corder in Maria Marten being directed by serial killers 22 x 30 inches, oil patel, 2013

Sketch 3 from a storyboard, The Elephant in the Haunted Castle

Tod, seated, watching the burning of the Elephant and Castle Theatre 16.5 x 23 inches, oil pastel, 2015

Narrative storyboard for The Elephant in the Haunted Castle, 2015

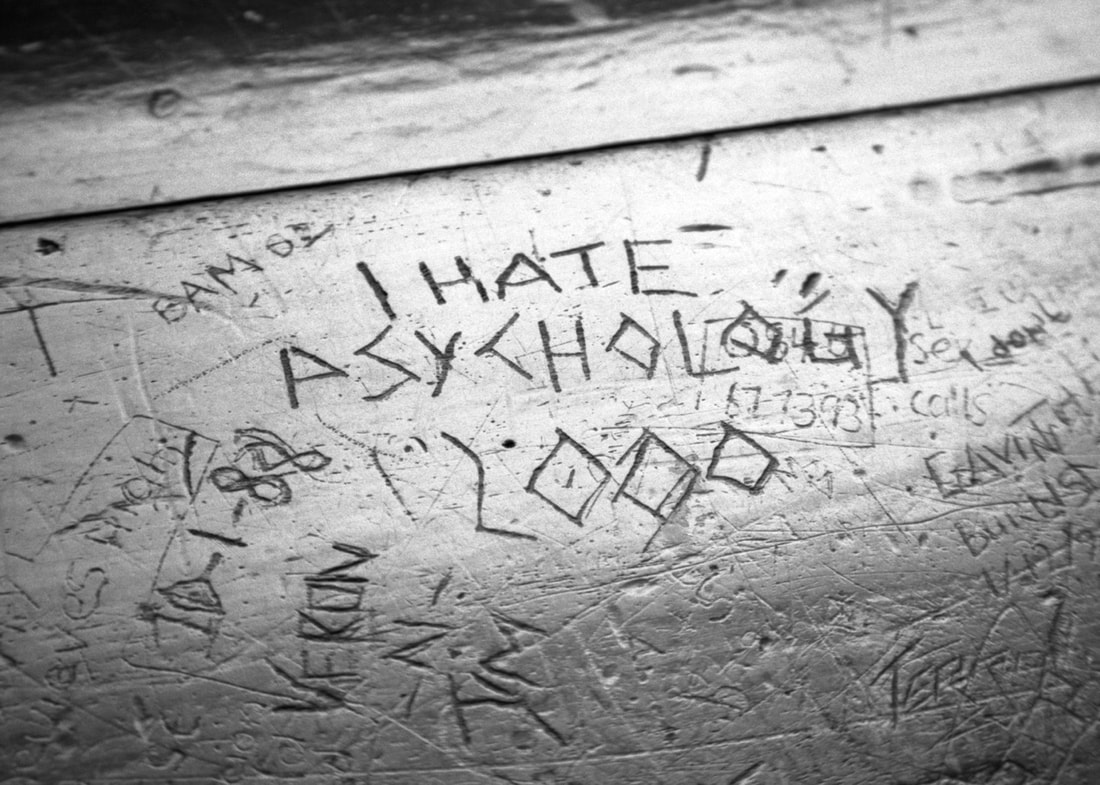

Tod became a minor British film star of the 1930s and early 40s, often appearing in adaptions of his stage plays. These "quota quickies" were made on shoe-string budgets. Modern audiences would grudgingly call them camp but cheerful. Film scholars have analysed certain films in terms of their social dimension, the themes of capital and labour. In terms of performance, Tod is ripe and fruity in his portrayal of villainy. One moment, the patriarchal squire, lusting after a country wench. The next, with his yeast in the bun in the oven, he chuckles before "polishing" the wench off to an unmarked grave. This is all set within a narrative that has basic motivation and plotting; however, this brings me reassuringly, full-circle, to the Terror I witnessed at the ABC that exhibited similar tropes. I'm not sure how accurate the press releases were in describing Tod as Europe's first horror star. The Face At The Window (1939) is a rare example of melo with "horror" motifs. I don't think the conventions of horror meant anything to Tod. He was not the director of any of his films, whereas he was fully in control of all the theatrical productions. You get a better sense of the quality of these when you listen to a radio broadcast or a vinyl pressing. The films are also more truncated and diluted for the Board of Censorship: at the end of the film version of Maria Marten, the hanging of William Corder is off-camera; a more explicit sequence had been shot but did not find its way into the final print. Also of interest is Tod's theatrical productions of Spring-Heeled Jack. In the play, Tod plays the villain lurking in the trees of Epping Forest. He then swoops down to plunge a hypothermic syringe into the leading lady and chuckles over "Two and half pints of lovely blood." I'm not sure what Jack was planning to do with the blood. Is this a plot where our beloved NHS is transfused by the private sector of blood merchants? We have comic accounts of Tod wearing a harness under his costume, attached to wires and being yanked up into the fly loft by the stage crew; springing in and out of scenic trees and occasionally just left dangling in mid-air when something went wrong. Melodrama, horror, comedy - all rolled into one! Let's leave the final image and word with Tod as Sweeney Todd. In total, he played this role over two thousand times. At the end of most productions, there would be a speech and then an invite onto the stage for anyone who was tired of life. Does anyone want to try the murderous barber's chair for comfort? Tod was ever the practical joker. Not many took up the challenge. However, one day, as recounted by Tod, a man came forward, saying he had a row with his wife and was sick of life. So he sat in the chair and was about to be thrown under the trapdoor and onto the mattress beneath the stage, when his wife shouted out from the auditorium. No, don't do it! The quarrel was settled and their relationship patched up (we would like to think!). This is almost a comic form of melodramatic therapy. It also neatly illustrates how the audience had a very direct emotional connection to the world of Tod. "It is grand to be playing at the Hackney Empire again (in 1954) before I pass into the limbo of forgotten things." Tod is in the limbo of things. He is not forgotten. At the Battersea fun fair, the crimson sun hangs over the big dipper. Do not stand up. Hold tight. The rush of sky against land, holding hands, giggling. Toffee apples and candy floss; pocket picked as the Mod-Rocker's brawl. A child, lost and found as their balloon floats across the river. Wetting yourself with joy at the water chute, then hiding your peed crotch in the Ghost Tunnel. The coconuts are all shy of their targets and prizes: goldfish or doll puppies. Too old to hold hands in public: the lip stick on the glass, the cross necklace is thrown away. The haunting sound of an Irish harp, busker, with no pennies in a cap. The power station pumps out smoke that slowly drifts across the park. Good night sweet memory, tinged with sadness of the fun fair. The Fun and the Sadness of the Fair Artists book, 21 x 10 cm Oil pastels, pencil October 2018 This is an abandoned film that was being shot from the Mourne Mountains to the city streets of Belfast from 2003-2008. There was a narrative thread: A student who came from a farming background becomes a political activist and drug dealer. Under a shroud of mystery, they are reported missing. One year on, we pick up the narrative, as a family member, ex-bobby, recreates their last known movements. Murder, suicide or a staged death to start a new life? Audio from a lecture room: "It has been argued that there is no fundamental difference between fiction and history. What we know about Julius Caesar - Et tu, Brute? or "καὶ σὺ, τέκνον" Is derived from a long catalogue of narrative forms; Storytelling about him that has been rewritten by each generation. We know as much about Caesar as we know about Molly Bloom. Something is real but not necessarily what the historians are telling us. Your man, Derrida, said: "il n'y a pas de hors-texte." There is nothing outside the text and we should add mobile texting. All our lives are made up of texts that also function as personal anecdotes. This is not necessarily true, as obviously, somethings are true; That ghoulish head skating past the window right now, The underclass who face poverty and premature death Or the student loan and its implications for your survival; All these represent aspects of the real world.” Images are now presented as open-ended, encouraging the viewer to replay and reconfigure, making up their own story, characters or mood in a variation of a black and white silent film. The Metamorphosis of Vine to Wine Charcoal, 78" x 57" 2019 "Three bowls do I mix for the temperate: one to health, which they empty first; the second to love and pleasure; the third to sleep. When this bowl is drunk up, wise guests go home. The fourth bowl is ours no longer, but belongs to violence; the fifth to uproar; the sixth to drunken revel; the seventh to black eyes; the eighth is the policeman's; the ninth belongs to biliousness; and the tenth to madness and the hurling of furniture." From the play Semele or Dionysus by Eubulus, c. 375 BC I never knew my grandfather, on the Greek side, but am named after him, Constantinos; His nickname on the island was Barba Chedeli. He cleared all the stones from the valley to grow crops that were sold at the market. Built his own house, furnace and wine press where grapes were crushed underfoot. Drinking in moderation, but enough to loosen the poetics of song and dance. In the face of war and famine, he was quite simply, glass half full. I thought I knew my father, a Pole. But he could never talk about the war and famine that exiled him to England. Vodka was never enough to loosen the poetics of song and dance. He loved me but I don't know if he was ever truly contented. No words in any language could quench his half-empty thirst. The mist drifts down the vineyard and into the corridors of the mind. This is the story of four bowls plus one and four. Drinking rituals executed with no particular rhyme or reason, beginning or end. An Existential compulsion. Top, left to right: Ruin of house built by Konstantinos Christofis, oven and wine press Bottom: Valley of rocks cleared for cultivation of crops, Oinousses Musical refugee as the city of Smyrna burns 24x20" charcoal 2009 A cafe in Smyrna where a Greek lad brazenly sings about killing and raping the enemy; And as he staggers home, drunk, after closing hours, a knife is plunged into his stomach. He dies in the arms of his sister asking for a glass of water. The heavens finally open to provide relief to the unseasonal temperatures. The family are sharing a heady brew, performing the last rites with a night vigil. Tomorrow they will gather their strength to bury the elder. But the stomach of the corpse starts to rumble and the children laugh, contagiously. They and the dead have not eaten any food in three days. The radio broadcasts convey the indifference and desperation of the phoney war. The family decide to bury their prized possessions, including a crate of wine, Little suspecting that the Nazi's will plant a colony of new forests on their land; At the same time, neighbours are either executed, or forced to wear a yellow triangle on their back.  Bound and gagged 23x19" Charcoal 2010 The student on the Intercity 125 has a Cold-War identity crisis. Tucked in the breast pocket of his 1940s herringbone overcoat is a 50ml bottle of Glenfiddich And a notebook of Ted Hughes-inspired poetry written under the pseudonym of Marian Evans. The wonders of a comprehensive education and full-maintenance grants; With enough left-over change in the other pocket to fund decadent posturing. Thatcherism hasn't fully fucked up or revolutionised the country, yet. Every time she cooked a meal, pasta alla wild fungi, cooked in red wine, Trying to worm her way to his heart through the stomach: His stomach ached and gassed for several hours, kiss by kiss. Lilac Wine by Jeff Buckley was playing in the background. There is a lone child in the other room of the flat and it is hungry. With bottles scattered behind pot plants, cans crushed under sofa cushions, She has had too much to drink and vomits up a meal of alphabet vegetable soup. And now still retching, trying to divine the significance of letters in the sink...G...M...T.... Suspense with suspenders 24x20" Charcoal 2009 It's a hen cruising night at Camden, three over the clock. Sat on the edge of a kerb stone, dress semi-hoisted, bladder overflowing, She wants to leave her piss stain for all the zombies in town. England have been knocked out of the World Cup. Then. Commotion. Club-crawlers are alarmed. But as her eyes refocus, there is a female death-metal band running down the street. She laughs at this godforsaken photoshoot and dribbles more pee. Instinctively. Fingers. Instagram. He has a name in the art world for creative notoriety in the manner of Francis Bacon: Violently bragging about who dares wins, fuelled by drink more harmful than cocaine and heroin. Not to be outdone, his partner has left him for an Amsterdam retreat. They are cursed to fantasise about each other in hangover and high mushrooming cloud. The cuts and bruises still fresh on their respective bodies. There is a trade war between China and America. Tree as a thorn in my eye (Set design after Wojciech Has's Saragossa Manuscript) 23x19" Charcoal 2010 Donning hat and coat and slipping on dancing shoes. Le freak, c'est chic or is it the Can-Can? His or her mind is shifting in time and place. And this is the first time you fully recognise a problem with hearing and balance. All those drunken conversations and couplings, fading to static and then silence. The flesh, still willing, spinning you on the dance floor; until the world falls from grace. Your life was foretold in the opening sequence of the film, Le Plasir (1952), Where a masked young dandy celebrates life on the dance floor, then collapses. How is that possible? Perhaps, if we cut out the liver and rip-off the facial mask, Everything in the spurting toxic blood will be revealed as both ancient and Science-Fiction. L-R: Three generations: Konstantinos, Constantine and Kazimierz Gras

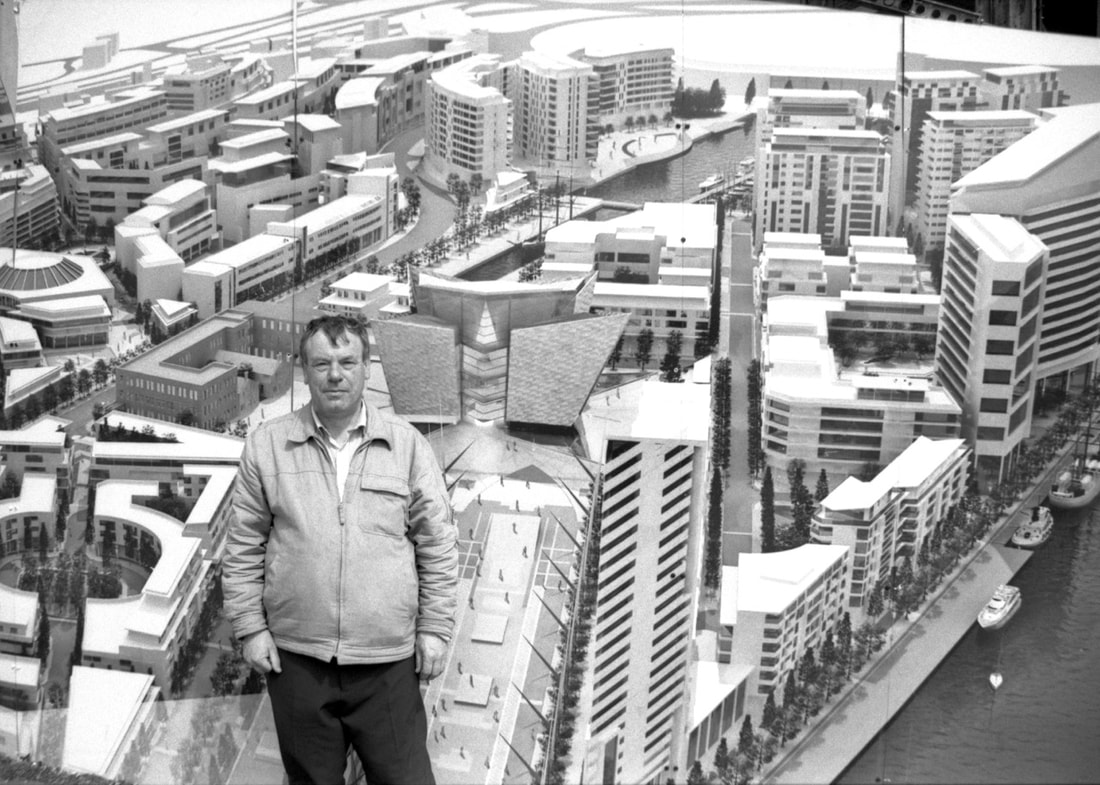

View of Bramley House (foreground), Silchester Estate high rises and Westway from the 17th floor of Grenfell Tower, 2015 If you put your ear to the ground, what can you hear? Perhaps Counters Creek - the subterranean stream that flows down from Kensal Green And threads past Silchester and Lancaster West Estates in North Kensington, London. If you start to excavate Lancaster West Estate, what fragments do you unearth? Possibly cups and saucers made by the Victorians and still serving post-war descendants. These are buried in the slum clearance of the 1960s and 70s. Now open up your inner being and listen to not just the stream and shattered shards, But the cries of people who were displaced by the town planners: During the first phase of redevelopment in this area Decades before the building of More West and the cladding of Grenfell Tower. The last words uttered, in-between sips of tea and beer. Here is one of those distant voices that rings loud and true: "To whom it may concern Having received your notice of your intention of developing this area And your formality to ask me to object, I SHALL, most sincerely, object on the below grounds: 1. Before I bought this property on Talbot Grove, I came to your Town Hall in person enquiring into any future development. A map was taken out, overlooked and I was informed that you had no immediate plan. I purchased the property. 2. After purchasing the property, I spent what is a large sum of money, to me (over £500) to insert a damp proof course, where after I was able to have a closing order removed. 3. I bought the property for private and undisturbed accommodation for my children. If their home had to be taken away, it would re-open a sore of housing accommodation and restrict their movements. 4. I have NO CONFIDENCE in the Kensington Town Hall. I have a genuine grievance which I believe is equally reciprocated by the Town Clerk and his colleagues. i have been in my opinion cheated and my feelings were expressed in various correspondence to him, Colonial Office and other officials, all to no effect. 5. As a negro, I have no status, I have NO ONE to whom I can go for sincere advice. NO ONE to whom I can seek redress. 6. If my property has to be taken by the Town Hall, I am sincerely afraid that it will be priced to suit the Town Clerk's wishes. I DO SINCERELY OBJECT Yours faithfully ........" North Kensington, late 1960s; consultation meeting regarding redevelopment Reproduced from Community Survival in the Renewal Process, PHD by Derek J. Latham, 1970 That was 1966. Here is another, less anguished, but equally desperate voice from 1971: "Dear Sir, Re: Town and Country Planning Act - 1962 Proposed Development at Lancaster Road, W11 Our main objection is that we fear not enough compensation will be paid, to enable us to purchase a similar property where we can live and carry on our business. A change of business will undoubtedly cause difficulties to our business. We feel that in running the Oriental Casting Agency, we are rendering an important service to the Entertainment industry by supplying them with mainly Afro-Asian artists. We are the oldest established Agency of this type in London, and we provide a livelihood for many Afro-Asian actors, actresses and models etc. A change in address would have considerable effect on the growth of the business, which has, in the past few years, been very marked. We have carried out numerous improvements to the property that was purchased in 1964. We would like to make it clear at this early stage in the proceedings that before we could agree to the development taking place, we would insist on the following points: a) Either we are provided with an alternative house of a similar type and condition, suited to our requirements. Or we are provided with adequate compensation. b) When and if we come to an agreement with the G.L.C. over this matter, we will be allowed at least ten months to enable us to make arrangements for the transfer of our business to the new address. Yours faithfully, .........." The Oriental Casting Agency. I suspect they might have supplied the plethora of Afro-Caribbean actors used in Leo The Last; the powerful film about an aristocratic slum landlord who is radicalised by his poverty-stricken community and whose townhouse is destroyed in the process. It had just been filmed on Testerton Street prior to that being demolished for the Lancaster West estate. Testerton Street, west side, 1969; where all houses are painted black by the set designers of Leo The Last RBKC Local Studies and Archives Walkway at Lancaster West estate built over Testerton Street Left: Salambo Mardi (acted by Christine Richer) Right: Leo The Last (acted by Edward Daffarn and Constantine Gras) Oil pastels, 16.5 x 23" 2015 We can trace a line of community protest through official and non-official channels. The ones that are officially recorded, pre-internet, are the petitions taken to the town hall. They tell a story of how residents organised themselves and attempted to shape the urban development of what was to become Lancaster West estate. Petition 1, June 1968 A petition was presented by Cllr. Douglas-Mann, urging the council to consider the plight of residents living within the boundaries of the development scheme who were unfurnished tenants. The recent housing survey undertaken by the Notting Hill Summer Project had shown that there were 167 furnished tenancies and all the families living in these cramped rooms, often without heating or water, were in need of being rehoused. Social workers and community organisers were raising this as a major concern. This petition was signed by 1,194 residents with 538 within the development area. The council at the time was under no obligation to rehouse furnished tenants but would consider cases of genuine hardship. The priority was given to those on the waiting list. Petition 2, June 1969 The following statement and petition was handed in to the Deputy Town Clerk by Mr J. Denham of the Lancaster Neighbourhood Centre. He and 30 children and 2 mothers had marched from North Kensington to the town hall. "To the Council, Sirs, We are told that the infant mortality rate of our borough is 40% higher than the average for the other London boroughs. We feel that child care in this borough is as good as in any other. Our conclusion is that the bad and often insanitary housing prevalent in North Kensington, overcrowded conditions, and lack of playspace and amenities constitute a direct threat to the health and happiness of all children in North Kensington. In view of this we urge: 1) That there should be more provision made for the rehousing of large families under the Lancaster West Redevelopment Scheme 2) That no family shall be evicted under any clearance scheme, whether they are furnished or unfurnished tenants 3) That North Kensington should be considered a housing emergency area and that all available local and national resources should be mobilised to see that every family in North Kensington has a decent house. Lancaster Neighbourhood Centre." The council generally regarded furnished tenants as mobile and of temporary duration, but would consider for rehousing those were who were long-term residents and who had genuine hardship. Petition 3, Nov 1974 Cllr John F. S. Keys presents a petition protesting at the conditions of the roads and footpaths around the Lancaster West Redevelopment Area. This was signed by 250 local residents. "We call upon the council to take immediate action to eliminate the danger to pedestrians, cyclists and motorists." The Council noted the concern and although this was beyond the normal resources of its cleaning service, would consider the possibility of introducing an Environmental Code of duties for contractors. Petition 4, July 1978 A petition signed by 135 residents and children of Lancaster West Estate calling for more open play spaces in the area. The council believed the residents were not aware of their plans to include more play spaces in the development. Petition 5, May 1979 Cllr. Ben Bousquet presented a petition from tenants of the Lancaster West estate urging the council to reconsider their policies of switching off the central heating at estates at the end of april and extending services until the end of may. Petition 6, November 1981 A petition was presented signed by 238 residents which contained the following "prayer": "We the undersigned residents of the Lancaster West estate demand that the council gives priority to resolving the problems caused by the plague of cockroaches, bugs and other insects in our homes. Further, we understand that these insects constitute a health hazard and we are taking legal advice to our rights against our landlord, the council. Meanwhile, should nothing be done we may consider withholding our rent and rates until those insects are eradicated from our estate." The council noted that cockroaches had gained a foothold in ducts and pipes at Grenfell Tower and Camelford Walk and were responding to this. Although a pest, they have little medical importance beyond the psychological effect of their unpleasant appearance. It was difficult for the council to access flats as a blanket treatment would be carried out to prevent further spread; legal forced entry might be required. The other insects mentioned are thought to be ants which appear from time to time on the estate. Tenants would be left to deal with this themselves. Edward Daffarn reading from a petition handed to the RBKC Scrutiny Committee, 2015 Petition 7, January 2016 Grenfell Tower Residents address RBKC Scrutiny Committee The residents had invited me to attend and document this meeting. This is a summary of the speech given by Edward Daffarn: "Thank you for allowing the residents of Grenfell Tower the opportunity to inform the Scrutiny Committee of the ill treatment, incompetence and plain abuse that we have experienced at the hands of the TMO during the Grenfell Tower Improvement Works. I am speaking to you in my capacity as a Lead Representative of the Grenfell Tower Resident Association, that was formed through adversity, in the summer of 2015 with the support and encouragement of our local MP, Lady Victoria Borwick. To back up the testimony of Grenfell Tower residents to the Scrutiny Committee members of our R.A recently conducted a quantitative survey of leaseholders and tenants to measure levels of resident satisfaction / dissatisfaction as a result of the TMO's handling of the Improvement Works. The findings of this survey are truly shocking. The survey revealed the following facts: 90% of Grenfell Tower residents have reported that they are dissatisfied with the way in which the TMO has conducted the Improvement Works. The survey found that 68% of residents said that they had been lied to, threatened, pressurised or harassed by the TMO. The survey also revealed that 58% of residents who have had the Heating Interface Unit (HIU) fitted in their hallways would like them to be moved to a more practical and safe location. As a result of the findings of our survey and with the support of Lady Borwick, the Grenfell Tower Resident Association is calling for the Scrutiny Committee to commission an independent investigation into the Grenfell Tower Improvement Works, not least, so as to prevent the traumatic experiences of local residents being replicated when the RBKC undertakes the Improvement Works to other tower blocks in North Kensington." Link to full speech on the Grenfell Action Group blog. At the Scrutiny meeting, the council agreed for an investigation to be undertaken on behalf of the residents. However, this was to be managed by the TMO. I was artist in residence at Lancaster West estate from April 2015 - June 2016 where I interviewed all of the original architects about their vision for the estate. I was not allowed direct access to Rydon and the other contractors tasked with the renovation of Grenfell Tower. Although commissioned by the TMO to make a short positive film about the works and to produce an art work for the new community space, I found myself deviating somewhat from the brief, especially once I started to listen to and record the life stories of residents. For a previous project, I made art with residents from Silchester Estate that drew on the social and mythic parallels with Leo The Last. This time around, I felt more like Leo, the individual who is observing and then directly implicated in the ensuing struggle that was taking place between residents and TMO/contractors/council. The film I made was a one hour portrait of residents. This was visually admired by the TMO, but was rejected as not fit for PR purpose. The art work made by children during the Grenfell fun day also languished and was never displayed in the tower after the works were completed. Silchester Baths photograph, protected during building works in the lift lobby at Grenfell Tower, 2015 It should be noted that throughout its forty-year plus history, Grenfell Tower only had one art work on display. This was an evocative archive photo of Silchester Baths, the Victorian building that was sited near the tower and which critically altered the original masterplan as it became temporarily listed before being demolished; it subsequently became car parking, green space and is now the site of the Aldridge Academy. There was never a description included with the photo to explain to newer residents why the Baths were of importance to the local area. I raised this with the TMO, but it was not important in the scheme of things. With my ear and inner being, I hear and then evoke..... Generations of residents living in houses at Testeron Road as they bathe their bodies and wash their clothes at Silchester Baths. The Baths and houses were caught in the red line of Slum Clearance programmes. A film maker took hold of Testeron Road prior to it being wiped off the map by the council. A false posh house was build by the film crew and then cinematically destroyed. Leo The Last tells us that we can't change the world, but we can change our street. Out of a ruined landscape, Testerton Walkway was built, one of the three blocks of housing that radiates out from the tower. Grenfell Tower was renovated from 2015-2016 with an artist employed on site. 72 people died in the fire on the 14 June 2017. When I think of Silchester Baths, Testerton Street, Testerton Walkway and Grenfell Tower, they should all be an interconnected and positive inspiration for how we manage space and housing; how this relates to play, heating, the control of pests and the consumption of social cups of tea. We symbiotically draw our health and wellbeing from the underground currents. Alas, those currents contain an equal measure of bitter tears and spilt blood. Tuesday, 25 July 2017 Grenfell Tower Inquiry Consultation on terms of reference A voice from the floor: "Looking at Grenfell Tower is like peeling back layers of the onion. At the surface a range of issues about building safety and failure of services to respond adequately to an emergency and tragedy. Behind that is the history of contempt and neglect that enabled those building regulations failures. But behind that is the reality of discrimination. The process that decides who it is gets burnt to death and who sleeps happily in their comfortable homes. Many survivors have put their fingers on that underlying reality. They were given unsafe housing and the terms to make it safe refused or ignored because of who they are. They are by and large on modest incomes, black and from ethnic minorities or migrants. This is not just about housing allocation in Kensington and Chelsea. Some of those killed were private leaseholders or private tenants. It's about how some people end up in worse housing, and then it's about how those people are treated as residents, as citizens, that they are effectively excluded from the important decision and that compounds their disadvantage. That's not just a problem in Kensington and Chelsea, but sadly there's nothing worse than Kensington and Chelsea." Artist studio at Shalfleet Drive, 2015

A map of the listed buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea I added Silchester and Lancaster West Estate to the list as they were threatened with regeneration |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed