|

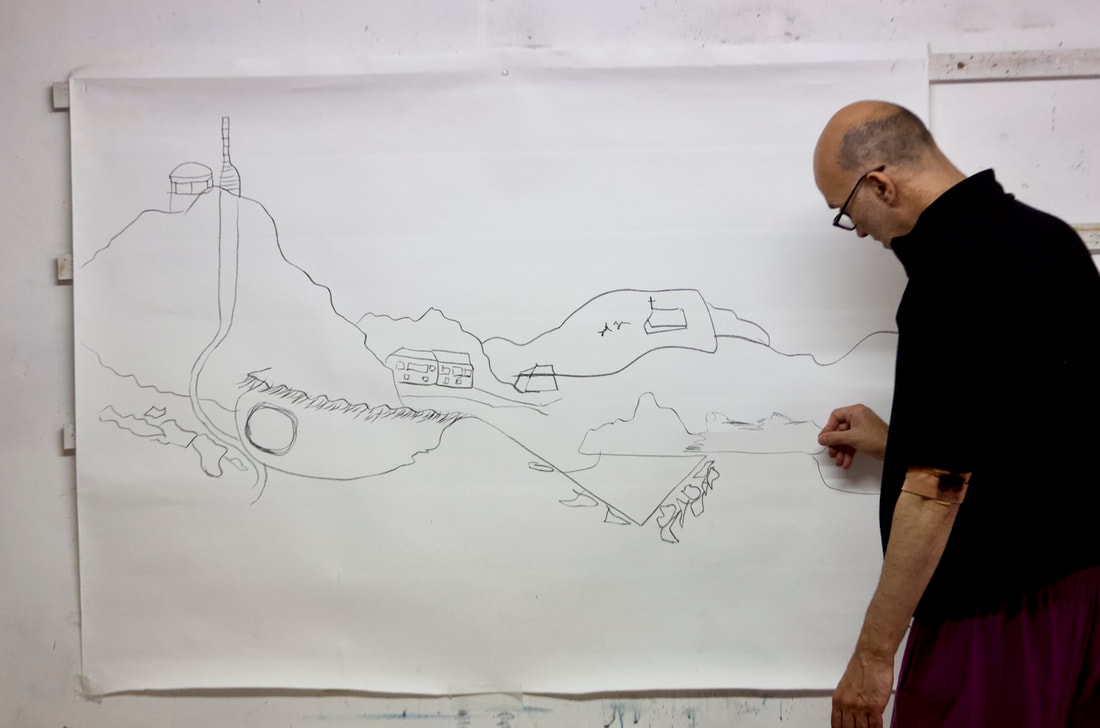

This is my first blog post in over two years. I would like to thank Brisons Veor Trust for supporting my two-week artist residency at Cape Cornwall. This came at just the right time in my life. I used the studio space (most distant house in photo above) to produce two large scale drawings. This was research for a book making project that I will running from 2024-2026. The book will be about the hope, joy and culture of community life at Grenfell Tower before the fire on 14th June 2017 that claimed the lives of 72 men, women and children. The research and development phase for the book has involved working with Hanan Wahabi and her two children. The first drawing I made in the studio was about my identity as an artist trying to breathe in a challenging world where local and global issues such as inequality, exploitation and climate change threaten the sanity of even the most robust and seasoned of constitutions. I took inspiration from the chimney on the top of the cliff overlooking the studio. This is the only surviving built structure of a once flourishing tin-mining industry. I first imagined the Victorian steam and noxious gases flowing up and out of the chimney and reverse engineered the process. The chimney and ducting, in my drawing, has been transformed into a network of larynx and trachea filtering out poisonous matter for my lungs. The ceaseless Atlantic swells act as a leitmotif, heartbeat, succour. On a cinematic level, I hadn’t anticipated the hypnotic views and wild call of nature. Each morn, I clambered up the cliff to the National Coastwatch Lookout Station. I filmed a short interview with Station Manager, Richard Saynor. I was touched by the role of these volunteers who support emergency services to ensure safety on this stretch of the coast. Our conversation touched on the desperate plight of migrants trying to cross the English Channel. How Richard’s job might be so very different in that context! I came to Cornwall for a creative and meditative break from London. But on a day trip to Mousehall, I turned a corner of the sleepy coastal village and stumbled across Grenfell Street. I then realised this must be where bereaved and surviving families came for respite holidays. After some googling, I contacted Esme Page, who provides this wonderful service with her charity called Cornwall Hugs. She told me about the Penlee lifeboat disaster when 16 people from her community died in 1981. And that in response to the tragedy at Grenfell, Esme campaigned the council to get Grenfell street re-signposted with a green heart of solidarity. Another discovery was forthcoming. Why had a street in Cornwall and a road in London been called Grenfell?.

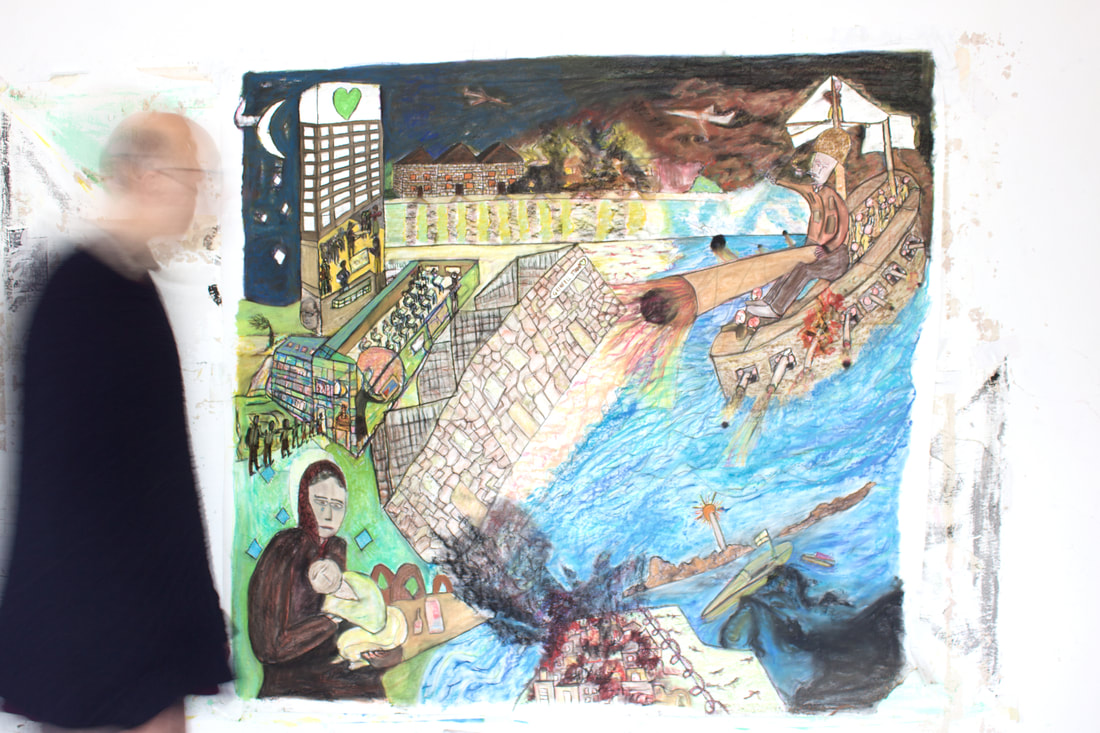

I visited the lovely church in St Just. On display, was a maritime flag from the battleship Revenge which had presented to the church by Captain Russell Grenfell after World War One. I learnt that the Grenfell family had Cornish roots. A Victorian member, Francis Wallace Grenfell, was a senior army officer who led British soldiers against Zulu tribes and also took part in the invasion and colonisation of Egypt in 1882. When he died in 1925, he was considered a war hero and a small back-road in North Kensington was named after him. Grenfell Tower takes half of its name from a former colonial soldier. Many of the victims of the fire were from former British Colonies. These historical elements are fused with burning contemporary issues in the second large scale drawing I made in the studio at Cornwall. This shows Grenfell Road and Street intersecting at a point of war and bloodshed. The drawing was being sketched as horrific events were unfolding in the Middle East. I have depicted Francis Wallace Grenfell astride a ship - firing cannon balls across the landscapes of North Kensington, Cornwall and the Gaza Strip. I felt at home here in Cape Cornwall, temporarily away from my troubled London. I documented the residents of Grenfell Tower from 2015-16 in their struggles to be heard during the fatal regeneration; this became the BAFTA and Grierson award winning documentary, Grenfell: The Untold Story. I had to hand over film and photos to the police in their investigation and have made short films for the bereaved and survivors they have used as part of their testimony. We live in a community that has experienced so much trauma. Has not received any justice. This summer, after almost seven years, the Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry is expected to publish its definitive recommendations and the criminal prosecutions will follow. We wait with bated breath. My next blog will not be posted in two years.

0 Comments

Over the past decade, I have had the unique experience of working with residents and the diverse communities on three social housing estates in North Kensington: Silchester Estate, Lancaster West Estate where Grenfell Tower is located, and, in the past few years, Wornington Green Estate. It has been challenging but has resulted in a rewarding body of work across multi-media, with film making always at the core. The bitter and sweet fruits of this labour come into sharp and public focus in the coming week.

On Wednesday 8th September, Grenfell: The Untold Story will air on Channel 4 at 10pm.

Before the tragic fire, I documented the struggles of Grenfell residents who raised issues and concerns about the work being carried out. Using footage never previously seen, this film forms a prequel to the disaster casting the tragic story of Grenfell in a new light. I've been holding onto film footage and photographs for over 4 years. It was handed over to the Metropolitan Police a month after the fire and over the years was made available to various members of the bereaved and survivors. Now that the police have cleared my use of the footage, it's the right time for it to be shared in a powerful documentary made by director and producer, James Newton and Daisy Ayliffe.. What were the circumstances that lead me into becoming an artist "in residence" at Grenfell Tower? I am deeply interested in the social aspect of art and the political issues this entails. In 2010, I made a commitment to working in and around the two estates of the Notting Dale ward in North Kensington - Silchester and Lancaster West. This patch of land has a fascinating and troubled history from slum housing to race riots. The estates that were built in the 60s and 70s were undergoing controversial redevelopment and this allowed me an opportunity to connect and explore. A nursery being closed down. A row of social housing on Shalfleet Drive was about to be demolished. Why and how were these taking place? It meant creating art that really connected with local residents. I may have been naive in approach, but not feeling. And it was based on this experience as a community-based artist and being employed by the V&A Museum as their first (and only) community artist in residence, sited in a council house about to be demolished for the More West development, that I caught the attention of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO). In 2015 they contracted me to make a short promotional film and large scale art work for Grenfell Tower as it was being renovated. I worked on this project for approximately a year. Early in my engagement, I made a decision to deviate from my contract and make a feature length documentary that ended up being called The Forgotten Estate. This was based on interviews with six residents who lived on the estate, in addition to the original architect and estate inspector. It was an attempt to use film to facilitate mediation and shared understanding between the TMO and residents who were in deep dispute over the impacts of the building works. The residents asked me to film meetings and a Fun Day. The TMO told me I would not be paid for this. The TMO never adequately engaged with the film I made seeing it as the same tired old voices that offered nothing new and marketable for them. I subsequently delivered a short 10 minute film to the TMO that featured no residents but portraits of the Boxing Club and Nursery that had moved back into new premises in the tower. I have only screened The Forgotten Estate on several occasions and have now withdrawn it from public viewing. The art work that I was commissioned to make also had a frustrating outcome. The TMO never hung up the completed work in the Tower and so it was not destroyed in the fire. It now resides in the offices of Grenfell United and a copy in the Houses of Parliament. Grenfell: The Untold Story will powerfully illustrate through the voices of residents, how a £10 million refurbishment that resulted in flammable cladding and insulation being installed, failed to meaningful engage with the desperate concerns of residents and the tragic consequences that resulted. The causes of the Grenfell fire are complex and multi-factorial. But this lack of engagement and duty of care to the residents was a significant failure. I hope that this film will have an emotional and soul searching impact on the wider public, politicians, local authority, architects and the building industry. Also on Wednesday 8th September a short film called A Spell For Wornington Green, was released by Channel 4 on the Random Acts platform. The film was shot over 2020-2021 during the Covid lockdown on Wornington Green Estate in North Kensington and follows the life cycle of two baby pigeons and the subsequent coming together of the community in direct action to prevent the felling of 37 trees as a consequence of urban regeneration by Catalyst Housing. Wornington Green Estate is half-way through a 20 year regeneration into Portobello Square. Nick Burton, who survived the Grenfell fire but sadly lost his wife, witnessed the felling of these trees on 1st March 2021 and commented: “My wife is dead because of Grenfell and they still won’t listen to the community.” Whereas at Grenfell, where I very much remained behind the camera or sketch book, I have since taken more direct action and set up the campaign group Wornington Trees. We are challenging the mass felling of mature trees in one of the most polluted parts of London. We have a second petition presented to the Council that was signed by nearly 2000 residents. It calls on RBKC to compensate us by planting an Urban Forest in North Kensington and to stop Catalyst Housing from cutting down any more trees until they have consulted. The regeneration of Wornington Green into Portobello Square involves knocking down and rebuilding 500 flats to rehouse its original community, plus the building of another 500 more at market rent or sale, where a one bedroom flat costs £700,000. The lack of real consultation and the resulting loss of green public space and the felling of 100's of trees during a climate emergency is the most deplorable part of what was once deemed a "flagship" regeneration by the Mayor of London.

Filming by Ilaria Di Fiore and music by Taozen.

This summer at the pop-up Portobello Pavilion in Powis Square, I displayed several large scale drawings from a series called Wornington Green in Black and White. They tell the narrative story of Wornington Green Estate.

Drawing 1: The Squalor of Wheatstone on Screen

Charcoal 2019 This is based on a newspaper article from 1975 that described how a local resident, Mrs Leq-Roy, borrowed a video camera and made a 20 minute documentary about the infestation of mice, dilapidated ceilings, rotten 'death-trap' flooring and overspill urine running down the walls of the houses on Wheatstone Road. Residents were calling for their slum houses to be pulled down for redevelopment.

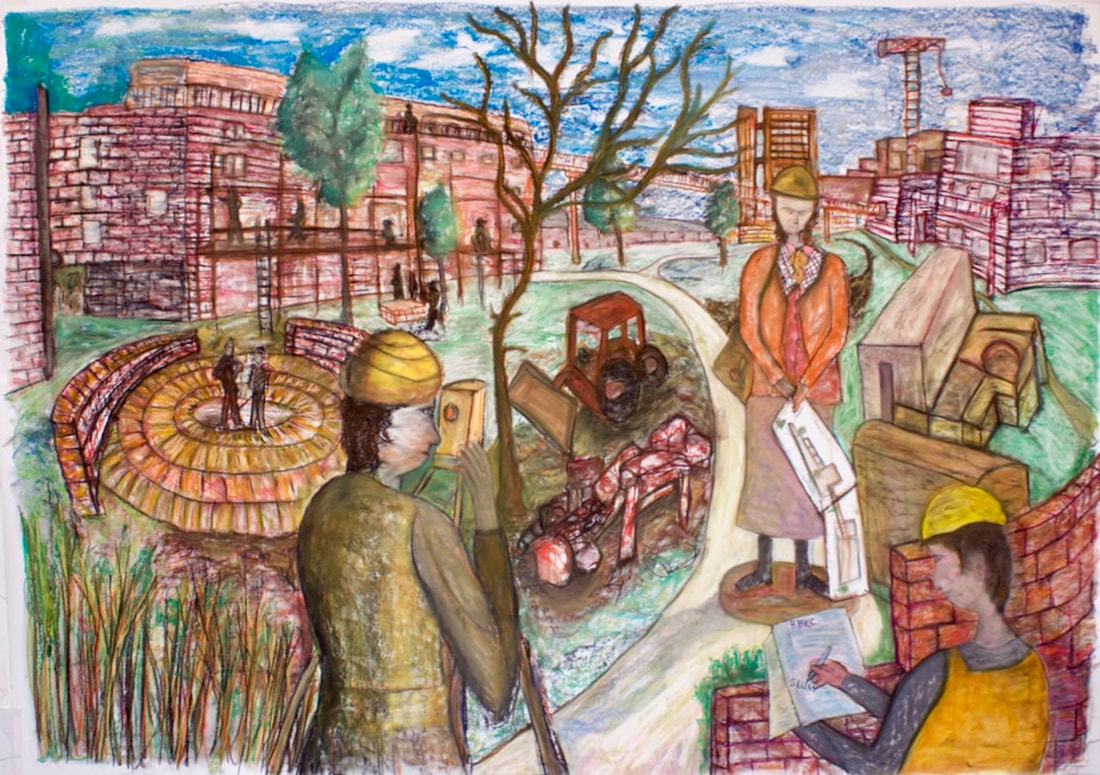

Drawing 2: The Whole Scheme represents a 21st Century Slum

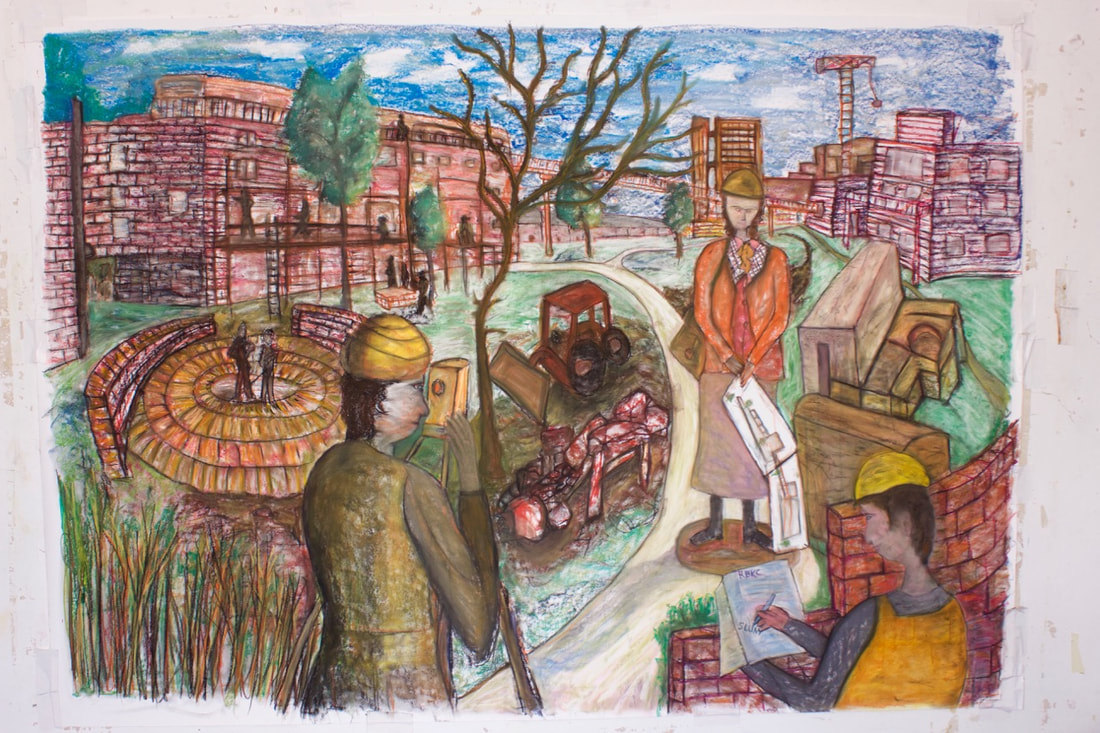

Pastels 2019 This illustrates the lead architect for Wornington Green Estate, Jane Durham, as she oversees the building of the Murchison Road Development that became Wornington Estate. Also present are representatives from the Council's Housing Department. One of whom, in archive records from 1975, stated: "Having had the unique opportunity of being able to view a finished block, it should be obvious that it is an architectural disaster and to repeat this form all over North Ken will be a Planning Disaster! The whole scheme represents a 21st century slum."

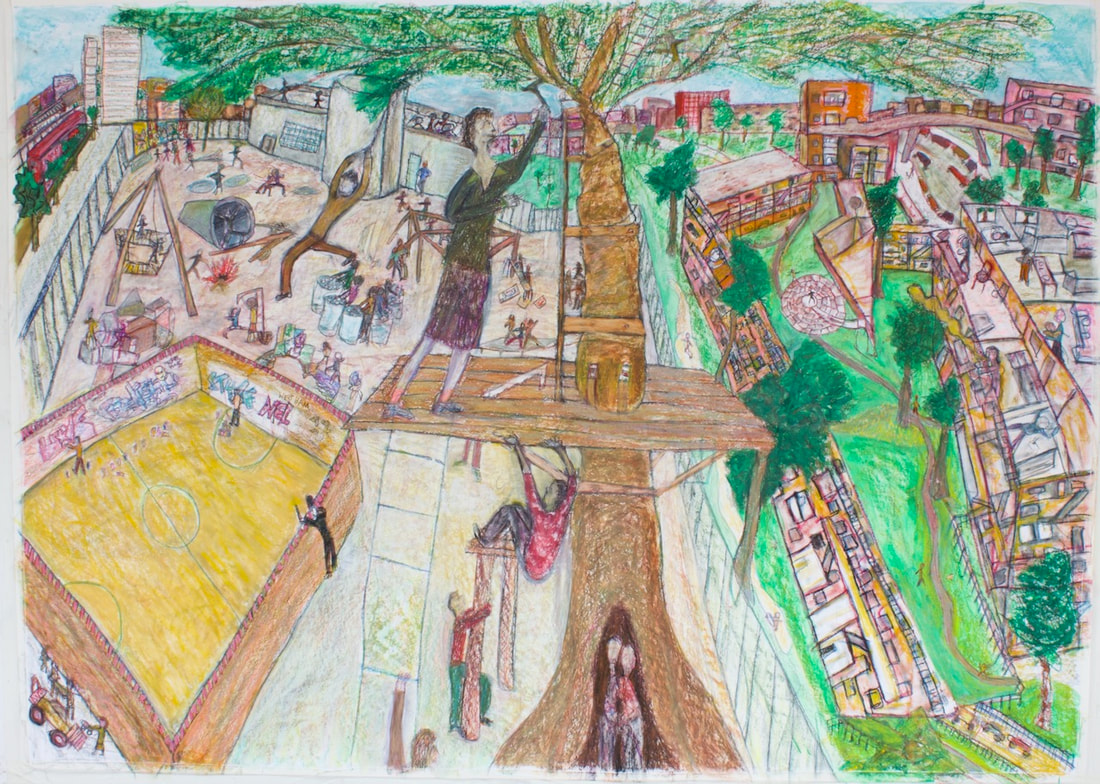

Drawing 3: Building a tree house at Venture Centre

Pastels, 2021 This drawing takes its inspiration from Wornington Word, a heritage project, that documented the voices of residents on the Wornington Green estate. In particular, an audio recording made by brother and sister, Latifa and Rachid Kammiri, who grew up on the estate and played at the nearby Venture Centre (the oldest standing adventure playground in the UK). "It was beautiful living here, it was absolutely the best thing ever, I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else because you were always safe. And we had the Venture playground right next to us which was totally different. Filthy yes because it was just all – it wasn’t even mud, was it, it was just like black dust everywhere. Our parents never used to like us to go there for that reason, you know, because you’d go there clean and come back like mechanics. But it was great. I think what I liked about it most when you went in there, it wasn’t health and safety, you just did what you wanted to do. You had to build your own activities, your own swings, your own slides, you know, from scratch. We literally built the Venture playground together." Footnote: the historic Venture Centre is scheduled for demolition during Phase 3 regeneration of Wornington Green and will be relocated in new premises in Portobello Square. Drawing 4: The great storm of 1987 Charcoal, 2021 This is based on another archive record and a recent telephone conversation I had with Margaret Cairns-Irven. She moved into Watts House on the estate in the early 1980s and described having central heating for the first time - "It was like it hugged us." At this time, the trees on the estate were in full bloom and while a keen gardener and nature lover, Margaret recollected that there were just too many in close proximity and the roots of one had grown into her garden making it difficult to plant anything. The drawing also includes a recollection she made about the Great Storm of 1987. During the night, corrugated sheeting had been ripped off the roof of the Venture Centre and flew over Watts House and she observed the frightening scene of a tree being blown down the middle of Wornington Road at 40mph. But humorously commented - how it was well driven and managed to avoid all parked cars!

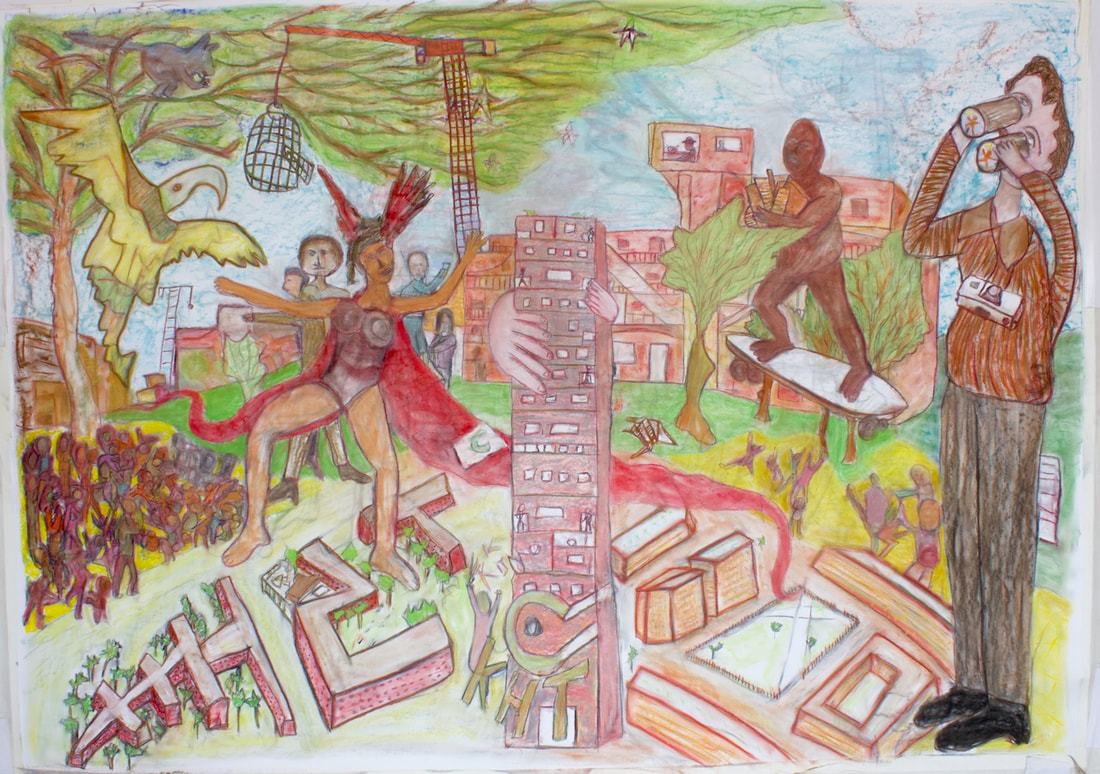

Drawing 5: Resident lead regeneration 1990 and Kensington Housing Trust / Catalyst led regeneration in 2010

Pastels, 2021 This drawing fuses together past and present regenerations on the Wornington Green estate. In 1990, the residents worked with Kensington Housing Trust to upgrade and install security entrances across the estate. In the archive, a resident newsletter had the optimistic and comedic image of King Kong proudly clutching the new security entrances. In my drawing Kong is bursting through the trees with joy. On the bottom of the picture plane, you can see the original estate with its interconnected blocks and walkways (left channel) alongside the 2010 Masterplan for Portobello Square (right channel). The contemporary architects plan to return the traditional street pattern made absolutely no attempt to build around and incorporate trees into the design. There are several other sweet notes and off-beat flavours in the image. These include the dancing and frolics of Notting Hill Carnival revellers. And the bird-watching of Keith Stirling. He is a life long member of the estate, who had campaigned for decades against the lack of maintenance and proactive management. Keith would resign from the Residents Steering Committee in 2020 in protest of Catalyst's plans to fell 42 mature trees and this inspired me to join him in taking our first petition to the Town Hall.

Drawing no 6 - March 1st, 2021.

Pastels, 2021 This drawing illustrates the coming together of the community to protest the felling of 33 trees on Wornington Green estate in March 2021. Two women from our community were arrested. Film of this features in A Spell For Wornington Green. I am planning a gallery exhibition of all 6 drawings.

On Saturday 11th September, from 11.30-2pm in Waynflete Square on the Silchester Estate, the Residents Association are holding a public meeting with the Council to share ideas about the future of the estate and how to spend the Grenfell Housing Legacy fund. At the same time in Waynflete Square, we are holding a launch event for the Art For Silchester book that was postponed by the Covid pandemic. This was an arts project I ran from 2018-20 for residents of the estate. Please drop by and see our amazing book and art work. Silchester Estate was earmarked for complete regeneration with the loss of its lovely green spaces. It was only the Grenfell fire that stopped RBKC council from carrying this out. Please visit the lovely square with its beautiful trees. The Last Garden In The Kingdom, Winter 2019 Visited by Ford Madox Brown Isabel Archer Derek Jarman Harry Ross and Helen Scarlett - O'Neil And Dominic Grieve Acrylics, pencil and pastel, 80 x 57 inches The Squalor of Wheatstone on Screen, 1975 Pastels, 80 x 57 " 2019 The Whole Scheme Represents A 21st Century Slum, 1975 Pastels, 82 x 58 " 2019 Two drawings from the past or are they storyboards for a future film? I never can quite tell about the journey of an art work and how it might be transposed or riffed upon once it leaves the studio. But what is the backstory? Over the past decade, I've had the unique privilege and challenge of working on art projects that have documented the vibrancy, celebrated the architectural history and explored (or exposed) "regeneration" that has impacted on estates in North Kensington. My mainstay has been Silchester Estate where I found my feet, had a studio flat and made my first deep connection with residents. I thank them for the support and creativity they have shared with me over the years. The projects at Silchester include: Latymer Mapping Project (2012-13) in collaboration with group+work, V&A Museum Artist in Residence (2014-15) and Art For Silchester (2018-20). I have also had a "career" defining sojourn at Lancaster West Estate and Grenfell Tower (2015-16). And this year, I have been welcomed on the Wornington Estate to assist in making a film called The Wornington Word - A People's History of the Wornington Estate as the estate is being completely knocked down and replaced by a new housing development called Portobello Square. I recently came across two archive documents from 1975. First up, a newspaper clipping titled The Squalor of Wheatstone on Screen. This has inspired the narrative drawings above that flow down on the left channel. "Stark shocking facts of appalling housing degradation and deprivation that is now a way of life for many North Kensington residents has been dramatically illustrated. The scene was a gathering of Wheatstone tenants who were witness to a video recording of the squalor and health hazards that most of them knew only too well. A 20-minute documentary revealed the decaying state of the Wheatstone area - infestations of germ-carrying mice, dilapidated ceilings, rotten 'death-trap' flooring and overspill urine running down the walls. The screening of the insight into the ghetto land was made by the Wheatstone Residents' Association who borrowed video equipment in a bid to speed up and nudge the Council into redeveloping the area. This was the aim and purpose of Mrs Leq-Roy's documentary who did not only the production but the interviewing as well; a disturbing but professional chronicle of life in Wheatstone which any T.V. company would have been proud of." Secondly, illustrating the right hand channel drawings, we have an RBKC Council Environmental Plan note. This was written at the same time as Mrs Leq-Roy's film is being screened. It conveys the thoughts of the council representatives who are overseeing the Murchison Road Development that will become Wornington Estate. "Herewith are a set of drawings for Murchison Road showing the way Chapman Taylor have modified the scheme following Committee's comments. Could I have your obs. please. My own views are that... the whole scheme still represents a 21st century slum." "Having had the unique opportunity of being able to view a finished block, it should be obvious that it is an architectural disaster and to repeat this form all over North Ken will be a Planning Disaster!" It should be noted that in the narrative drawings we have Mrs Leq-Roy filming a mouse-ridden cooker as a "seven-year old girl drug addict - so badly affected by the conditions that she was hooked on sleeping pills" is trying to sleep under a line of damp clothes. In the companion image, we have the lead architect of Wornington Estate, Jane Durham (1930-2019), with her vision of the estate, being challenged by the builders and the council. This might be a first. Residents make a campaigning film to have their houses demolished and built as part of the estate redevelopment. At the same moment, members of the council are stigmatising the estate being built as an architectural disaster, a slum in the making. Such an irony - only in North Kensington, I hear some locals mutter! If it still exists, I would really like to track down and screen this film made by residents in 1975. Can anyone help me? If successful, this would be the third film I've unearthed from private archives or collections and brought back to the community of North Kensington. In 2010, I got permission from John Laing to use excerpts from Western Avenue Extension (1970) in my film, Flood Light and the Laing film about the building of the Westway has now been added to the Westway Development Trust archive. In 2019, I contacted Robin Imray, to screen his wonderful short film made in 1974 about the campaign to save the bath and wash house on Silchester Road. This was screened as part of a curated programme at the Portobello Film Festival called Washing Dirty Linen In Public. We walk in the cracks of archives, buildings, institutions - where stories and films need to be reclaimed!

Last summer I had to put Glourie House up for sale.

The damp and decay could not be maintained. Empty rooms were haunted by ghosts, the ghosts of my ancestors. They don't seem to know how to act and are afraid to confront me. I can't stand hearing the squeak of their fearful, retreating footsteps. Never once have I heard their voice. An American tycoon had opened a golf course on the coast road. Sunk in a dram of whisky, I reluctantly sold him my ghosts. It's my last day to water the plants and have high tea. Brick by brick, the house and its contents will be stripped and shipped to the States. My ghosts are going to become part of an oldie worldie theme park, yahoo. Maybe next summer they will speak to others through me.

Drawing and words in creative response to The Ghost Goes West (1935), starring Robert Donat.

Glourie House For Sale (2019) 93x58" oil pastels

There is a voice behind the ghost and the silence of pictures: British film star, Robert Donat, 1905-1958.

Before we get to the voice, here are a few memorable facts about this now largely forgotten actor who was so highly acclaimed in his lifetime. A poetically inclined child, Robert would recite Shakespeare in the streets and on the trams of Manchester. "Oh there goes that funny boy again, saying those queer words." A rising star of the stage, he broke into movies with a rebellious laugh. Donate had a screen test for Men of Tomorrow (1932) but the director, Leontine Sagan, thought he was a terrible ham and caused the struggling actor to break down into peels of laughter at the futility of the test. Two days later the test was seen by the head of studio, Alexander Korda. He was so impressed with the jollity that he hired Donat on a three year contract. Breaking into movies isn't usually a laughing matter. Donat made one film in America, The Count of Monte Christo, but disliked the cultural experience, and never went back. Hollywood Studio executives chased him through the courts, but Donat struck a lucrative and unique deal to have high-budget films made in England, culminating in Goodbye Mr Chips (1939) for which he won his Oscar. Several generations of American actors recognised the subtle and charismatic charm of Donat's performances. Spencer Tracy sent him a postcard applauding his decision not to work in the States; otherwise us bums would all be out of business. And then Jack Lemon commented: "The best screen actor to me, without any frigging question, was not even Spencer Tracy, but Robert Donat. And what made him so good was that he always seemed to be acting in the first take of a scene. You have the feeling he has never said those particular words before. You should have the feeling that the film was shot in sequence, even if it wasn't. You should believe that the scenes were acted in chronological order, with no embarrassing little jarring discrepancies of emotion. Robert Donat had that, too – the wonderment that made us think those things were really happening to him." Vicky Lowe describes the appeal of Donat cutting across class boundaries: "Therefore, despite being categorised through his stage work as a classical actor, alongside the likes of Gielgud and Olivier, on film, there is a palpable difference in Donat’s aural presence. Whilst nearly all of the famous stage/screen actors of the 1930s came from a comfortable (usually Southern) background, Donat is a notable exception. Michael Sanderson has researched the parentage and place of education of famous actors of the time including Charles Laughton, Leslie Banks, and Laurence Olivier. All except Donat went to either private school, university or both. Whilst his image fits in with the rest of his peer group, his voice can be interpreted in terms of its difference to his peers. His voice in this country, therefore, was recognised as being beautiful without being necessarily classified as ‘posh’: classy rather than class – bound. Kinematograph Weekly explains Donat’s vocal appeal in this way: ‘In a country of so many dialects and empire markets, spoken English should be unplaceable. […] You cannot ‘place’ Robert Donat’. ‘The best speaking voices in the world’. Robert Donat, stardom and the voice in British cinema" Vicky Lowe, 2004 I want to bring this homage bang up to date. We in Little Old England have endured several years of political chaos in a desire to shift away from the European Union in the direction of new alliances struck with America and other trading blocks. To resolve our current stalemate, we are going to have a winter General Election and another intense period of party political sound biting and speechifying. It's interesting to note, that many of Donat's characters in the movies of the 30s and 40s, in the context of that turbulent political period, have memorable set-piece speeches to deliver: whether as a politician in the Houses of Parliament (The Young Mr Pitt); or as a legal big wig (The Winslow Boy); or in The 39 Steps as Richard Hannay, on the run for his life, seeking sanctuary in a lecture hall and having to deliver an impromptu speech about Scottish politics, grouse shooting and the fisheries. So as I listen to Conservative, Labour, Liberal, Brexit, SNP and other voices, I will filter them through to one exquisite moment in the film, Knight Without Armour. As we Brits bicker and fight to play a role on the world stage, perhaps we can rewind and take a leaf out of Dietrich and Donat in this Russian Revolutionary (shades of Zhivago) saga. Dietrich is an aristocratic prisoner of war. Donate is escorting her to a trial and an unknown fate. In this memorable scene they romantically bond over the poetry of Robert Browning contemplating how to live, laugh and love, moments before a Cossack attempts to slit their throat as the scene concludes. As a cautionary footnote, Knight without Armour, ends on a rather tame note. That doesn't really matter. We often don't succeed in threading together the complex narrative of art and politics. Last summer, you could fall in love with a film star and the fragility of performance and voice.

Jordan Stone, film maker in conversation about his parents, Barbara and David Stone,

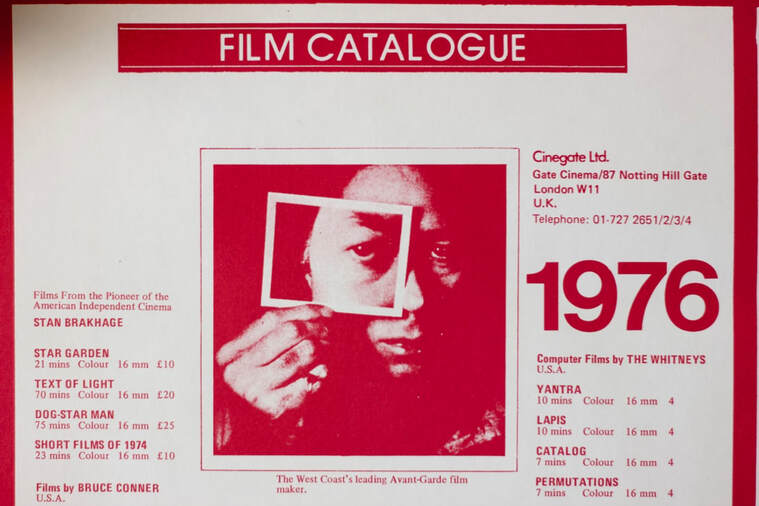

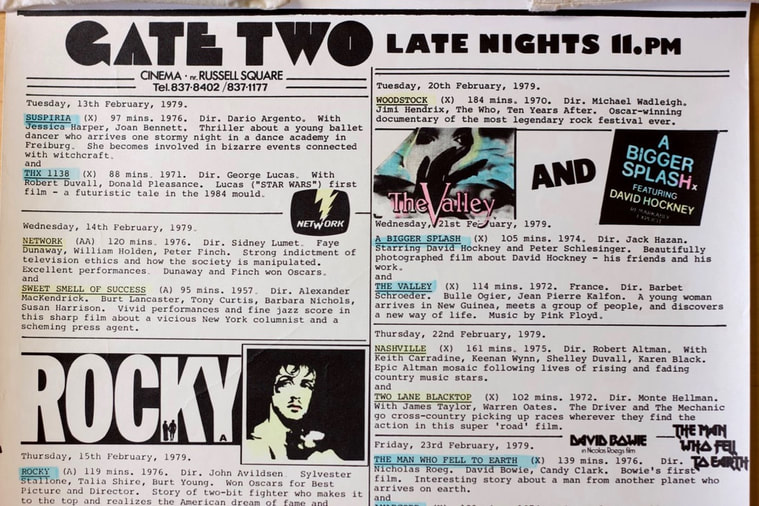

who opened a pioneering art house cinema in 1974 at the Gate, Notting Hill. The family moved to England in 1971. I think what my father originally wanted to do was to open a New York styled delicatessen in London where you could get bagels, cream cheese, smoke salmon, pastrami on rye bread. That was his original plan. But my parents had a passion for underground, avant-garde and independent cinema. They had been attending film festivals from the very early 1960s, whether it was Cannes or Venice. They were the creators of the Spoleto Film Festival in 1959. And so they were very familiar with European directors, the press, film critics, historians and writers. They had also been involved in the various film art movements in New York. They had made films themselves and also produced films with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. So at some point, they realised that there was this huge area that was missing in film exhibition and distribution. And that was their talent: to create a distribution and an outlet, a cinema, at the Gate in Notting Hill for showing these independent films. At that time films were still being dubbed for UK release. And there were films that would not have found a way out of their country of origin. My parents combined their passion with the business. But taste has to obviously come first. You have to create that and show it to the public. In America there is also a certain passive-aggressive approach to business whereas in England, it's a lot more passive. Maybe aggressive is not the right word, but they were more proactive, a term used today, but not used then. And so, it's like everything aligned at the right time. A cinema became available for them in Notting Hill. It was called the Classic. I think the previous owners couldn't afford to keep it going and that was the moment to strike as it were. What you have to realise is that the distribution company Cinegate and the Gate Cinema went together. What we distributed was what we showed. In the Cinegate catalogue, we had a huge collection of experimental cinema from Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Stan Brakage and the Mekas Brothers. And what also was remarkable were the late night double bills, mainly from other distributors, mostly American classic and cult films from the 1930s up to the 1970s. My parents created this culture of late night screenings that started at 11pm and went on till 2 or 3 in the morning. No one else was doing that. I still bump into people who tell me that they saw this film 25 times because they went to the late night program every other night. And unlike other cinemas, the Gate was open 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year including Christmas Day, New Year's Day. We were open every single day. Other cinemas started to copy us with late night programming. The Scala started doing the all-nighters at weekends. The Electric that was just down the road from us, on Portobello Road, was a repertory cinema. Peter Houghton who ran that cinema had perfect taste. It was an absolute fleapit at the time, but they created their own cult even before the Gate. But it was very different from our cinema. They would show a week of Hungarian movies and then ten days of German New Wave and then a week of Charlie Chaplin. And they showed a lot of films that we distributed that fitted perfectly into their programming. But they weren't opening movies. We were and they were independent, art house films. There is a nice little story. The Electric went through many periods of running out of money and my father insisted on lending them some. It was a real beautiful little moment unheard of that one cinema would help out another in the same area. I don't think my parents started up their operation thinking in a competitive way whatsoever as opposed to enhancing the whole concept of British Independent cinema. A few years later, once everything was going well, my parents had a good relationship with EMI and Barry Spikings, its head at the time. He had produced The Deer hunter and EMI had a cinema in Bloomsbury. But they had no idea what to do with it. They didn't know how to program it and so they gave it to my parents and the rent was completely reasonable. After a while, Gate Bloomsbury (now the Curzon Bloomsbury) was divided and had two screens. Then some short time after this, the same thing happened with Rank who had a cinema on Camden Road. My parents took that over and it became Gate 3. And finally, in the basement of a Mayfair hotel, there was this wonderful, tiny, super-exclusive cinema with just 40 or 50 seats. That became Gate Mayfair. When we first opened in Mayfair, this must have been about 1980, Mephisto, which was a huge success and went on to win Best Foreign Picture Academy Award, that was shown at Mayfair on a second run. I think it was playing for 9 months. My sister says it was shorter. But it felt longer. The majority of art house movies were definitely not American. The only American art house movies would be ones made by first time directors who sometimes had a distribution deal with a major company. And so the only way you would find out about these films was going to film festivals where the producers would be at Cannes, Venice or wherever they were trying to sell their films. My parents would be looking out for these types of films. Jonathan Demme was a Roger Corman protégé and his first couple of films we opened, I think we even distributed them. There was CB Radio and Melvin and Howard.

There were moments that brought great controversy that fed into the success and mythology of the Gate. Derek Jarman's first film, Sebastian, for example. The dialogue was in Latin and there were scenes of men making love to each other. It was definitely not pornographic, definitely an art film. But they were under a lot of pressure from the Board of Censors which was run by a guy called James Ferman, who was also an American. There wasn't much love between him and my parents. There were lines around the corner of the Gate Notting Hill because the only film prior to that which could be conceived of as a homosexual film was A Bigger Splash. That was a film about David Hockney and we ended up showing that at the late nights. But Jarman's film was a full-on feature film and made by someone we had never heard of. We had a lot of celebrities and famous people coming to see that film in 1976. And then a couple of years later with the Oshima film, In The Realm of the Senses, where you had two lovers making love throughout the film and in the end the girl cuts the man's penis off. That film was refused a rating by the Board of Censors. My parents came up with a way around this; which was to turn the cinema into a club. So people had to be 18 and pay a minimum 25p or 50 pence membership and then they could buy a ticket to see the film. But as kids growing up, we were told to stay away from the cinema because my parents were expecting to be raided by the Home Office every day. I also know that for that film to be seen, they put together a list of very well known people who had signed a petition demanding that this film be allowed to be shown to the general public. This was not just film people or from the entertainment industry, but also politicians.

The regeneration of Notting Hill had not happened at this time. That was much later. Everyone who was everyone was coming to the Gate. You had to imagine Harold Pinter living down the road and he would want to see everything. We had people who loved film and wanted to see films that the film critics were writing about and that would not otherwise have a chance in a lifetime of being released in its original form. We had punk musicians, artists and photographers, a lot of theatre people and of course, the general public.

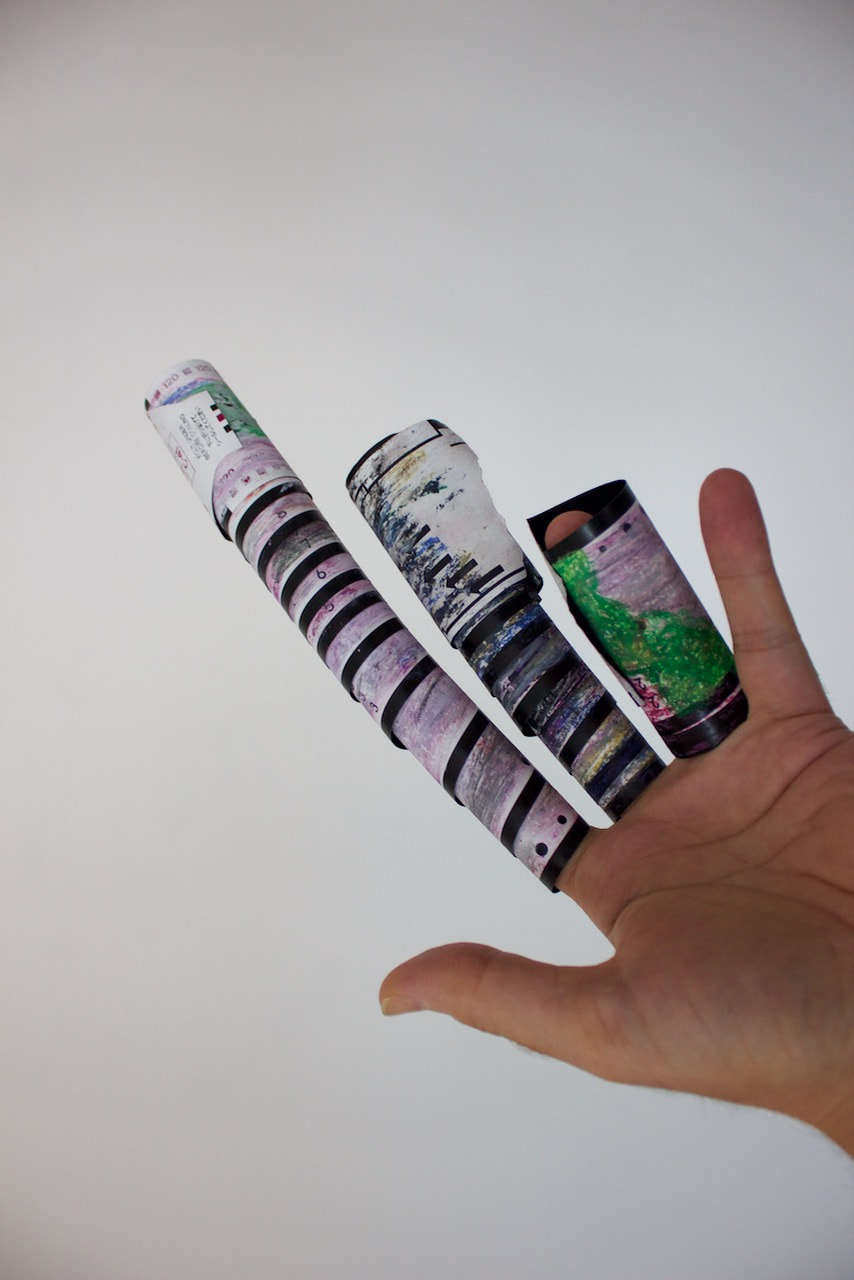

My father was always charging a little bit more at our cinema. There was a reason for this because we were showing films exclusively. I think our first ticket price in 1974, for Fassbinder's Fear Eats The Soul that opened the cinema, was 60 pence; but after a year or two, this went up to 90 pence. And of course, we were an art-house. You were going to pay to see art. He wasn't trying to rip anyone off. It was a very exclusive approach however. And my father was actually quite short and the rows in the cinema were based on his leg- room. What he wanted to do was get as many seats in as possible. So we did have a reputation of having very thin rows, but that was based on the fact that he was quite short. I think we had 282 seats. If you look at the Gate today, my father would be surprised what it turned into with the sofas, the tables, the feeding and drinking during the film. I remember we were one of the first households that had a video projection system at home because film-makers from around the world were sending us films to watch. We grew up watching films that never made it into distribution. We had friends coming over to the house who never knew what a video was, VHS or Betamax. And we had equipment that was flown in from the states. This was set up in one of the rooms in the house, a screening room. Actually whether we lived in New York or London, my father always had a 8mm and 16mm projector set up in the house. Saturday night we would be watching films. They were very social events with film critics, Chris Petit, Nigel Andrews, David Robinson and filmmakers. We were also very friendly with someone who worked at the National Film Archives and every weekend he would come with a 16mm print under his arms, something that was 40 or 50 years old. My mother would do a big dinner and then we would all sit and watch the movie. That was a large part of the Stones' reputation. From the age of 11 or 12, I was working in the cinema and the Cinegate distribution dispatch office. Cleaning the films, packing them up and taking 16mm and 35mm prints to whoever was renting them. My brother and sister were also working with me in the cinema, making popcorn, tearing tickets and in the projection booths. I was also an actor and then at the age of 16, I had already started a video production company. Then a producer friend of ours asked if I wanted to be a runner on one of his films. That's how I started making my way up as an assistant director and have never stopped. I still am a first assistant director on feature films, commercials, and music videos. I was based in L.A. for a long time, too. And now I'm operating out of Italy. I look after a lot of the filmmakers who come to shoot here and I've turned that role into a type of service producer as well. I've produced projects with Sofia Coppola, Mike Figgis, Spike Lee. I’m a filmmaker myself. My films are not commercial and that is a result of most of my life working on other people's movies whom I've learnt so much from. The lesson that my parents ingrained in all of us is that you have to do what you feel is right - for you! And we grew up in an anti-commercial atmosphere. Anything that was American studio was the devil. We knew from the beginning that people who went to America to make films, compromised their creativity, because a producer or the studio said we want more tits and ass and more violence. However In the last 5-10 years in America, I've found that there has been a rush of films that are very independent. But most films can't be made unless they have a distribution deal. The film studios and media companies will put money into a film for its distribution rights. The filmmakers are not dictated to as badly if it’s a non-studio film because they have got the money just for distribution. So what's happened is that it's allowed much more of an independent approach to American filmmaking. There are many different structures to put a film together. You can raise money privately; you can raise money through pre-sales, through distribution sales, money from the studios, from several companies or countries. Tax incentives. It's a whole quagmire of things before you can get interest for the project. But if American studios are involved, the more control they have over the finished product. It's a different process for a European or a Chinese filmmaker. I saw a space to do commercially what my parents had done in London during the 1970s. I ended up for a while programming two cinemas in Milan in the same style as the Gate. I also created CinemaStone and this is not just a production service company, but it also dealt with film and event programming. I grew up doing what I was destined to do.

Barbara Stone Unpublished - trailer for film written and directed by Jordan and Veronica Stone

Jordan Stone's website Poster art work from the Barbara Stone Archive recently deposited at King's College, London And which will be available to view over the coming years Drawing by Constantine Gras: When a kiss fans out Watercolour, pencil, ink 9.5 x 12 inches, 1994 Link to film event called Emotion and Economics - A history of the Gate Cinema Obituary for Nigel Whitbread (1938-2019) Modest, talented architect with a passion for walking, travel and sports cars Nigel Whitbread was born in Kenton near Harrow. His parents had a grocer’s on St Helen’s Gardens in North Kensington and the family moved in 1949 to be nearer the shop. That was Nigel’s home from the age of ten to his death. After attending Sloane Grammar School, Nigel joined the firm of Clifford Tee and Gale where he served his apprenticeship demonstrating a great talent for drawing for which he became renowned and which he taught later on. He went one day a week plus night school to the Hammersmith School of Art and Building. Subsequent to this he became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. But it was Nigel’s time at Douglas Stephen and Partners that was the most influential time in his career. It was a small practice, but doing important things and at the forefront of design influenced by Le Corbusier and other modernists. It was there that Nigel worked with architects from the Architectural Association and the Regent Street Polytechnic: Kenneth Frampton who was the Technical Editor of the journal Architectural Design; and Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Bob Maxwell who both spent most of their careers in the teaching world. Nigel remarked that it was like going to a club with the bonus of doing terrific work. In the early 1970s Nigel went to work with Clifford Wearden and Associates on Lancaster West Estate. It was a huge job for a small group and unusual for councils to use private architects in those days. The whole scheme had been well prepared by the time Nigel joined to lead the team in designing Grenfell Tower. While a lot of brick had been used in LCC and GLC buildings, he thought that putting bricks one on top of the other for twenty storeys was a crazy thing to do. So insulated pre-cast concrete beams as external walls, were lifted up and put into place with cranes. The concrete columns and slabs and pre-cast beams, all holding the building together, were also designed in response to Ronan Point, the tower that partially collapsed in 1968. Nigel remarked that he could see the tower standing in 100 years time. In 2016, Nigel visited Grenfell Tower at my invitation, when I was community artist in residence. He visited residents in their flats for the first time and enjoyed hearing how they viewed the spacious flats (built to Parker Morris Standards) and the stunning views. It is impossible to know the sadness and anger he must have felt as he witnessed the tragic fire that occurred on 14 June, 2017. Nigel retired after working at Aukett Associates for 30 years. His projects included the Landis and Gyr factory North Acton and Marks and Spencer's Management Centre Chester: two award winning buildings he co-designed. As a director of the practice, he had a lot of responsibility, but spent time mentoring younger architects. Nigel was happy in his retirement and in his travels over many years, including recent trips to India, the Himalayas and Colombia. He continued to use his skills in helping his local resident’s association draw up the St Quintin and Woodlands Neighbourhood Plan which was accepted by the local authority under the Localism Act. He will be remembered by his friends and family as a dignified, humorous, generous and inspirational man. Silchester and Lancaster West Estate Open Garden Estate Weekend, June 2016

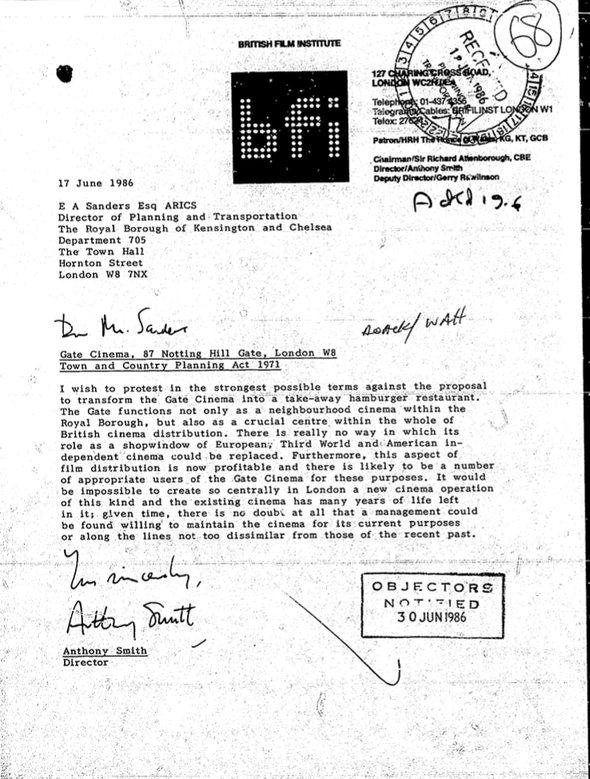

Here's a link to an interview with Nigel and the other architects of Lancaster West Estate. Anna Bowman: "I really enjoyed Emotion and Economics. It was great to see Adam Ritchie's film set in NY and the extract from the fascinating film about RD Laing. They were a wonderful reminder of the past and the damaged video/film just added to the atmosphere. Constantine Gras' curation was superb and the live actors, speakers and extracts of films worked really well. His film about the garden near Grenfell tower was very moving - a poetic and considered response to what happened there." This is a documentary film of an event curated by Constantine Gras that won a special distinction prize at the Portobello Film Festival, 2019. It celebrated the history of the Gate Cinema, Notting Hill, London from 1911 to the present day. A narrator told the story of emotional creativity in the world of boom and bust capitalism. A monster mash-up of films included silent shorts, extracts from the films of British film star, Robert Donat, and art house cinema of the 1970s. The Electric Palace - Silent Years (1911 - 1931) 0:00:00 Introduction by the narrator: "The cinema experience as we know it started with the opening of picture houses between 1907 and the first World War. This period saw an unprecedented investment when businessmen shed their cautious approach to risk in search of massive financial rewards." 0:01:33 Introduction by Horace Sedger, American business man who opened the Electric Palace picture house in 1911: "There are many nay-sayers, who put us down! Who think films corrupt young and impressionable minds. They say there is no future in this newfangled technology. Humbug we say! The cinema is a mere infant." 0:04:34 Extracts from silent films available to view on BFI player The Production of a Map (1917), Delhi Durbar (1911), Demonstration of Suffragettes (1910) Tilly and the Fire Engines (1911) 0:06:35 A poem written by a projectionist from the silent cinema. "I'm here in a fireproof box that is hot as a stokehole floor, And my head goes round to a clicking sound and a rickety motor's roar And my nose smells films and my tongue tastes films And my eyes they can see film too Till I'm sick unto death at the thought of films." The Embassy - The Coming of Sound (1931 - 1963) 0:08:50 Mary and Jorge visit the cinema to see a Robert Donat film. 0:10:30 Dr Victoria Lowe, University of Manchester, on Robert Donat’s "Art of acting in the age of mechanical reproduction." 0:14:14 Film extracts from Goodbye Mr Chips (1939), The 39 Steps (1935) and Knight Without Armour (1937) 0:16:07 A letter to Robert Donat from a fan: “Will meet you at midnight on Sunday outside Boots.” The Classic - A full blown repertory (1963-1974) 0:17:29 Adam Ritchie introduces the film he made in New York in 1966 with Yvette Nachimas called Room 1301: “The dangerous film stock was then destroyed, so there is no way back.” Followed by screening of film (15 minutes long). A film about a worker lost in the maze of a high rise office block. The Gate as Art House (1974 - 1985) 0:37:08 Nigel Andrews, Financial Times film critic, shares his memories of the pioneering Gate cinema in the 1970s and the American couple, Barbara and David Stone, who screened and distributed independent movies from around the world. 0:43:44 Trailer for Barbara Stone - Unpublished (Film in production) Explores the life of a mother, filmmaker, teacher, distributor and exhibitor Written and directed by Veronica and Jordan Stone 0:49:32 Extracts from Fear Eats The Soul (1974) and Sebastiane (1976) Directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Derek Jarman To The Gate Picturehouse And Beyond Anthony Smith, Director of the BFI, 1986 “I wish to protest in the strongest possible terms against the proposal to transform the Gate Cinema into a take-away hamburger restaurant.” 0:51:38 Jonathan Barnett, Director of the Portobello Film Festival, introduces his film R.D. Laing On Iona: “They were all tripping on magic mushrooms and had a go at R. D. Laing because he cancelled a seminar. And then he gave them a talk about anger and had them eating out of his hand.” Followed by screening of film (10 mins) 1:02:50 The narrator: "We have glimpsed how the history of this cinema has been shaped by pioneering figures with one eye on entertainment or art and the other on box-office takings. Managing a sustainable business in a constantly changing world. We have experienced the power of film stars and their impact on the audience. We have celebrated the history of film made on fragile celluloid stock." 1:06:05 Constantine Gras on how he curated this programme and on the concluding film, Strawberries Are For The Future, which is about the garden (and gardener, Stewart Wallace), in the shadow of Grenfell Tower - a year after the tragic fire claimed the lives of 72 people. Short extract from the film. 1:11:16 Q&A Lee Ellwood, current manager of the Gate Picturehouse Dylan Stone, artist Adam Ritchie, photographer and film maker Jonathan Barnett, Director of the Portobello Film Festival They talk about how the Gate Picturehouse chain and potential for screening independent shorts, the Barbara Stone Archive that has just been deposited at Kings College London and the vibrancy of community activism and counter-culture in North Kensington. Many thanks to Jonathan Barnett and Lee Ellwood for facilitating this event. Jordan Stone for providing background research. Narrated by Jackie Kearns with performances by Richard Seedhouse, Claire Finn and Harvey Steven. Costumes by Adriana Solari. Filming and sound recording by Harry Green.

Photo above, from left to right:

Horace Sedger, director of Electric Palaces Ltd that opened the cinema at 87 Notting Hill Gate, in 1911. Barbara Stone, manager of Cinegate and Gate Cinema that opened in 1974. Stewart Wallace, gardener at Lancaster West estate who stars in The Strawberries Are For The Future (2019). The following is a conversation with Jonathan Barnett and Leona Flude, Portobello Film Festival director and co-ordinator respectively. They discuss a range of topics: the origins and ethos of the 23 year old film festival; the pleasures and pitfalls of independent film making and exhibition; the supremacy of European and world cinema over the current British scene; and the future of the festival. Constantine Gras will be curating a 2 hour programme of short films during the festival in September 2019 at the Gate Cinema Notting Hill. This will be called Male Emotion and Economics: The History of British Film from Cecil Hepworth to Derek Jarman and beyond. This will also be a site specific event with actors telling the story of the Gate Cinema, one of the first electric picture palaces to open up in 1911 at the dawn of the British film industry. Short films being screened include Jonathan Barnett's portrait of R.D. Laing (1984) , Adam Ritchie's Room 1301 (1965) and Constantine Gras's The Strawberries Are For The Future (2019). In addition, there will be another programme of films drawing on our local history and includes Washing Dirty Linen in Public (2019) and North Kensington Laundry Blues (1974); the latter is a film about the campaign to save the Silchester Road bath and wash house and has never been screened before. Jonathan Barnett: I used to be a roadie for a band called Here and Now who came from Ladbroke Grove. The big thing that they used to do was free festivals and free music. There was this free music thing happening in the Grove in the late 1970s, early 80s. At the time this whole area used to be really run down, a slum. You wouldn’t believe it now. But out of slums comes a great deal of creativity. And I was totally into all of this. Then these VHS camcorders came out so you could actually make a film for next to nothing which you couldn’t do before-hand. What got me going was the original video for The Message by Grandmaster Flash. It was filmed on VHS in the streets of New York and you could almost touch it. It was so real. And the fact that it was little bit amateurish actually made it look better than the stuff that was horribly professional. It also meant the means of production and distribution weren’t owned by the state. It was owned by ordinary people who could make films. So I filmed the carnival in 1982 and basically that’s what I did for ten years. I just filmed anybody that I thought was interesting with my VHS camcorder. Also around the beginning of the 1990s you started to get digital technology coming in. So this was the context for why we decided to do the film festival. It was started by these people called Massive Videos that was run by Barney Platts-Mills and Ghanim Shubber. Barney made these amazing films called Bronco Bullfrog and Private Road in the early 1970s. He was into making film with kids off the street and he wanted to have a festival. They got money from City Challenge and started the Portobello Free Festival. This was around 1996 and they didn’t charge filmmakers for showing or people for admission. The first two years we were in tents on Athlone gardens which was great. It was just supposed to be a platform for all those people making films and who had nowhere to show them. Definitely came out of the genius loci of this area which used to be a frontline for innovation and we were the place that did counter-culture in terms of film. Leona Flude: I was born around here and I think I met Barney via Courttia Newland who is a writer and is actually doing something now with Steve McQueen for TV. I used to go to school with Courttia and there was a group of us from Ladbroke Grove who started to go to Massive Video. Barney, Ghanim and Jonathan were there and telling us, yeah guys, make a film, just make a film. So everyone just mucked in. Someone would write a script, then we would go somewhere and film it. Then it got to a stage with needing to show these films somewhere. So the idea was conceived of having a film festival and it went on from there. But I have to say that without Barney and Ghanim, the festival would never have happened. They were amazing and inspiring, giving life and confidence to young people from the area who never thought that film was in their remit. JB: I always thought the Portobello Film Festival needed a Banksy figure. The tools are there now and anyone can make a film on a budget of nothing if they want to. But not a lot of the films are very good because they are self-indulgent. It’s the selfie-generation rather than someone who wants to tell a story. But there will be people able to use this technology and make a really brilliant film. Obviously, the documentary is the easiest one, because you just find someone who is interesting and you point the camera at them. Also it’s more intimate in a way if you are doing it yourself, rather than a great big camera crew and everything. The secret? It’s got to be interesting to other people. That’s the thing about Banksy. He is street art, but everybody loves it. We need a film maker doing the same thing, with a bit of story to it or somebody interesting acting in it with a bit of star quality. I suppose it’s only just happened. We’ve only had digital for a short while, so it will take a bit of time for people to get used to it. JB: What are the stand-out films? Guy Ritchie had his first film with us and also Shane Meadows. Sarah Gavron who made the feature Suffragettes in 2015, we had her film when she was a student at the National Film and Television School. Arguably, the films were better in those early days. L: They had a bit more depth to them. Nowadays they are all so self-obsessed and if you find a film has really high production values, it’s usually quite dull, which is such a shame. It is difficult sitting through those films sometimes. But the European films are amazing. JB: Yes. The European stuff tends to be of a higher quality, more challenging. I think film is regarded more highly as an art form on the continent than it is in England. Particularly good films are coming out of Spain and Ireland and Germany. L: And Russia. You just think to yourself, how are these people having these great ideas for films. JB: We get a lot of dramas that can be a bit dreary. L: Especially the one’s about crime. JB: Yes. They are made by middle-class people who probably don’t know anything about crime. There has always been good animation L: And The British films usually do good comedy. JB: The whole point is you make a film and other people have to watch it. So you want to leave them in a higher state than when they came into it. That’s what a work of art is about. People have to realise that they can do absolutely anything they want and they should not be trying to conform; if they want to conform, fair enough, go to film school and get a job as assistant director at the BBC. But if you want to be creative, use these tools that are available to you and do absolutely anything you want. The whole idea of a short is brilliant, because you can distill all of your bestness into ten minutes and that’s really quite exciting and a challenging thing to do. L: We have had a few really really good films. The one for me was German. It was an arty film about a guy smoking cigarettes. It was black and white and won best film or best art film probably over 10 years ago now. JB: N from last year was quite good. That was a send up of German expressionist films. It was clever and it wasn’t too long. L: And Jermaine and Elsie set in Ladbroke Grove about a guy looking after that older woman. JB: Yes. It was about this guy who was a carer for an old lady and it turned out that she was a racist. And he was black and gay. But she ended up really liking him. L: Cass Pennant used to submit a film every year and he’s gone on to do really good things for Netflix. The work he showed here was about football fans. JB: Casuals was about Millwall fans and their whole culture, the clothes they wore. That film was great. We’ve had a few top directors. Julian Temple showed his London Babylon here. And Mike Figgis. The last few years we are getting stuff from the Ken Russell siblings. L: I have to say that one of the best stand out evenings was the screening of The Passion of Joan of Arc that was made in 1928. JB: That was fantastic. In The Nursery did the soundtrack live with synthesisers that had these sound effects like bells. The actress who played Joan of Arc was amazing, her acting, her face. And to think they found that print in a can that was dumped in the back of someones house. L: For me that is the best. I didn’t need to go to another film festival after that. JB: One of the most exciting evenings we had was with Chris Cunningham. He used to do adverts and pop videos for people like Bjork. He was obviously the darling of the advertising world and we had this weird film of his, Rubber Johnny, a Frances Bacon type film. One minute there was nobody there and then about 500 people turned up and we could hardly fit them into Westbourne studios. L: The queue went all the way around. I knew who he was, but I didn’t know he was that big. And it was like what the fuck! We also had another great evening with Ladj Ly and he won at Cannes this year. JB: Yes! From a film called Les Miserables but I don'’t know if it was the original book. Ladj Ly came from one of the Paris suburbs. Whatever you say about England, it's far more integrated than France. Anyone who is ethnic minority they just whack them out to the suburbs, to the ghastly ghettos. So that’s where he’s from and they had a year of riots there and this guy filmed all the riots. L: And we brought their production team over here to the festival and had a great evening. I'm wondering if things were almost more exciting back then. JB: Culture has got very standardised of late. But one thing you do get at the festival, because we are kind of street level, is you get things when they are just starting out. The mainstream pick up on those good films that you first see at Portobello. L: And also I think from the film festival being free. There’s so many more free film events around London. JB: It’s inspired other people to do the same thing, which is great. Free is terrific. We have to thank the sponsors over the years for that including the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and The Westway Development Trust. We have this organic festival. It goes where it goes. We are not leading it anywhere apart from the fact that we are trying to keep it free. The foreign side of it which is programmed by Raymond Myndiuk will always be there because the foreign films are so good and they send them to us in droves. This year, we are doing three weeks at the Muse gallery with non-stop foreign films every evening. JB: Tim Burke who sadly passed away recently helped start the Pop Up Cinema under the Westway. It started when the Mutoid Waste Company did a thing there one Christmas. They turned a Wessex helicopter into a spider and they had all the top graffiti artist there. Chris Bailey from the Westway Development Trust brought in Barney who then involved us. I wanted to get in a cheap projector, but Tim said - no let’s do it with a professional one. He got that in and a giant screen, The containers were our idea. The top one being the projector booth. And so we started the summer after the Mutoids had been there. Tim was putting on stuff throughout the year. We had Dave Pitt from Inn on the green doing the bar and on a nice day it was a great place to hang out. We were at the Pop Up from 2010 to 2015. L: We would love to go back. JB: It’s hard not being there. We are trying to make film a live experience and that was the perfect venue. They say it’s location, location, location. We got twice as many people at the Pop Up because it’s on Portobello Road and it always used to be full at 5.30 before we start at 6. There was an excitement in the air. So the last three years have been a bit of a struggle. L: With us not being at the Pop Up, it's like we don’t have a home. JB: Yes. We need the Pop Up. And when Grenfell happened, we decided that we didn’t want to exploit it, which is what a lot of people were doing coming into the area. We wanted to do something for local people. So we’re putting on these shows at the Maxilla which is called A Song For Notting Dale and it's not making a big political statement or everything. It’s for locals telling them they are respected. L: In the future we want to secure funding, so that we don’t have to stress every year about paying the rent. Also getting the Pop Up back would be brilliant. JB: It would be great if someone said, here’s thirty grand a year. We’re not asking for a fortune. That’s cheap for a big festival that lasts three weeks. And then we could really go for it and put on more special events. And we have lots of old films in the office we want to digitise. In conclusion, some tips for film makers thinking of submitting to the festival: L: Get someone else to edit your work. When you edit, your just too emotionally involved and will end up trying to keep everything in. And don’t forget sound quality which is just as important as the visuals. JB: I would say keep it short and get someone interesting to act in it. There is nothing wrong with filming on the street. If your camera's in close, with a good built in mic, you’d get a good picture and this will save you having to light it. And do something interesting and original. If you have fun that will come across in the film. That’s what the original Shane Meadows films were like. He was obviously having a laugh doing it, even though a lot of it is complete nonsense, And when your film is on, come along and bring a load of mates. That’s the whole point. It’s a party. This is your version of Cannes even if it's the only film your ever going to make. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed