|

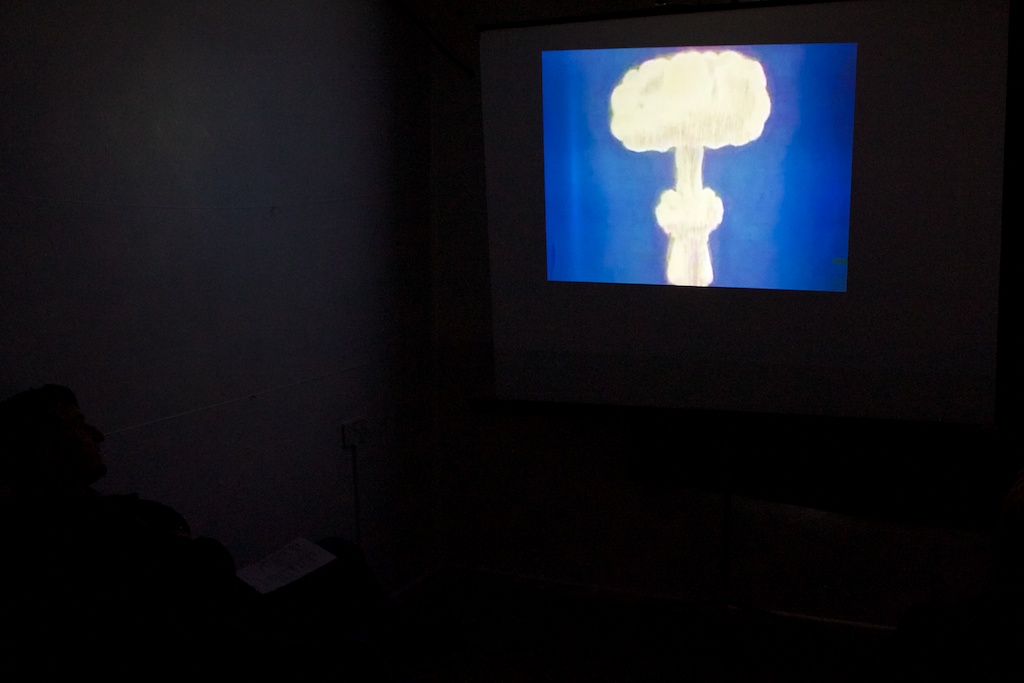

In my role as a V&A professional assistant, I was lucky enough to assist at Constantine Gras’ Open Studio event, as part of Kensington and Chelsea Open Studios in October. Normally when I’m heading to work for the V&A, it’s at the South Kensington landmark, a place with a myriad of its own very specific associations. I’m always overwhelmed by a sense of place when I am there. I get lost in the building every time, but I also always find out something new about the collections, the staff or institution along the way. On my way to Constantine’s Shalfleet Drive studio, part of a block of council estate flats about to be demolished, I reflected on what might be different about this project, as the V&A’s first ever Artist in Residence programme to be resident in another place altogether. For a start, the layout of the flat as someone’s home is very evident. Constantine emphasised this homely feeling by serving everyday food refreshments that you might have when you went round someone’s house - cups of tea, biscuits, crisps. The huge crane visible from the little backyard starkly also brought a sense of limited time to the space, providing a threatening counterpoint to the homely atmosphere. When I was there the cranes were working despite it being a Saturday - the work had got behind schedule, so Constantine told me. This really highlighted a strong sense of the space being on borrowed time. I was also excited to find out that the crane was operated by a woman, and spent a while out the back on tip toes trying to see if she was driving the crane that day. The film programme playing in the old bedroom of the flat mixed films about Constantine’s work with vintage public service broadcasting, including a really alarming film about how to survive a nuclear attack (apparently you should wait to hear from the authorities over the radio and you will be given instructions - not very reassuring!). The film based on a 1968 photograph showing the last resident's house before the Westway was built - part of this area’s cycle of decay and regeneration that has been going on for centuries - created a parallel and contrast to Constantine, the last occupant of this last block of flats about to be raised to the ground. A vinyl player and record collection were out on display. I had a lot of fun searching through for my favourite, soul and funk from the sixties and seventies, taking a short detour into the eighties with Grand Master Flash, of course. It was great to see not only the younger generation coming in throughout the day and finding out how to use a record player, having never really seen one used before, but also everyone who’d used to have one at the centre of their living room but had since forgotten. We used the memories and associations brought up by the record player and the surroundings to create a huge collaborative drawing on one of the walls of the flat. When I went for a walk at lunchtime, I had a sudden realisation that far from being in an area I knew nothing about, I was just round the corner from Holland Park, where I had briefly worked two years ago. The contrast in atmosphere and style of the neighbouring areas meant I had never made the connection, and my internal map of London swung sickeningly round in my brain to try to account for these two places being related as I walked along.

Like my many good discoveries made at the V&A, this one was made because I was lost. I also found the last remaining brick kiln in the area, next to another block of sixties-style council estate buildings. A small plaque on the kiln explains its dedication to the local people who worked in the industry, and the intensely difficult work conditions and living conditions they suffered. My day in Shalfleet Drive introduced me to a new micro-area of London, and emerging back from it into my own neighbourhood had me wondering what stories I’d missed in my own back yard. Time for me to get lost there too, maybe. Helen Innes, Illustration www.heleninnes.com

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed