|

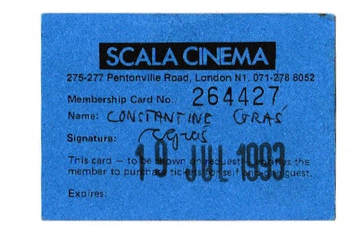

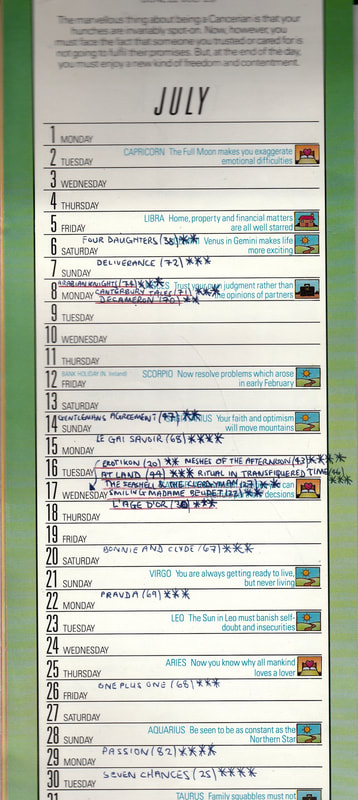

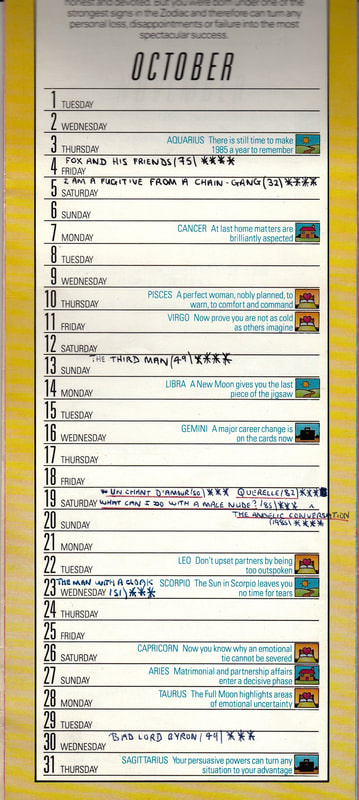

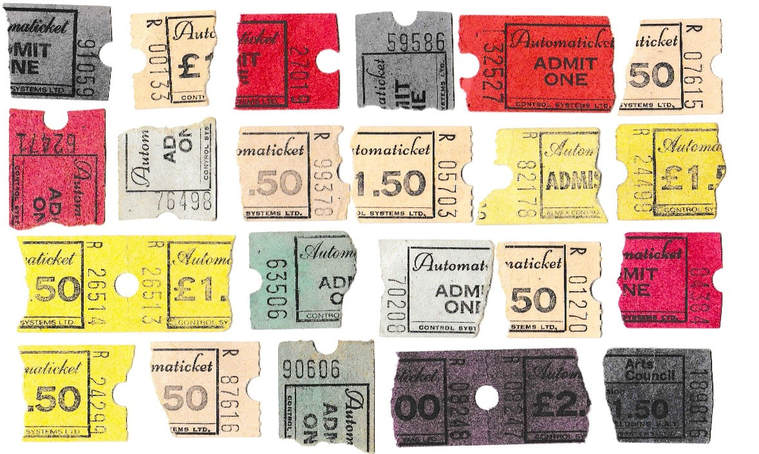

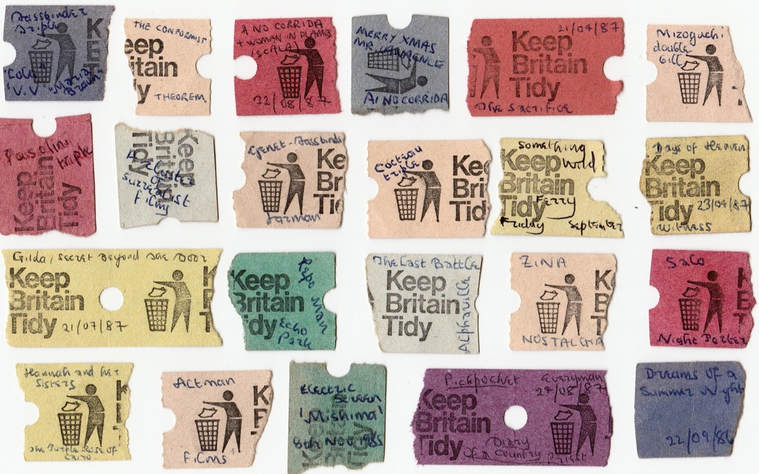

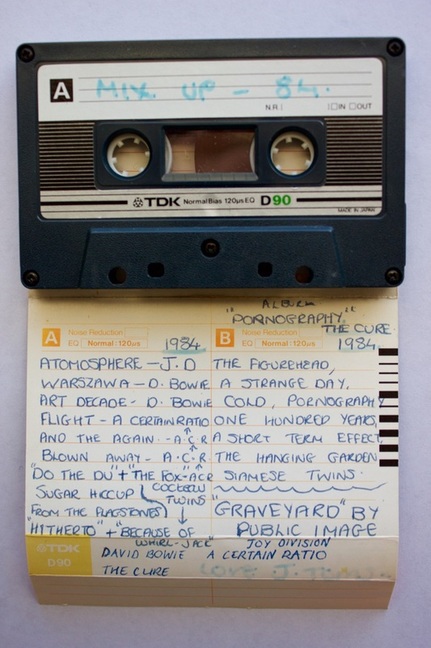

I recently treated myself to a double bill of The Angelic Conversation (1985) and Mirror (1975). I don't think any programmers have paired these two films before, but they resonate with each other, lyrically and visually, as well as offering divergent approaches to art based film making. Both were viewed on a computer screen, with the Jarman film rented online. However this screening of one film after the other was an act of homage to my golden age of cinema going as a teenager in the 1980s. After wee nippering at the ABC Edgware Road, I gravitated to the flea pit circuit that took in the posh Everyman at Hampstead and the grungy Scala at Kings Cross. During this period you could watch double or triple bill features in memorable combinations designed to shock and awe: The Exorcist riding on the back of Enter The Dragon; Terror followed by Savage Weekend (the rediscovered memory of Terror would inspire an arts project called The Melodramatic Elephant in the Haunted Castle); Fassbinder double bills; and, not for the faint-hearted, a starter, main course and dessert of Pasolini films. Also, certain films that should not have been coupled, such as the groundbreaking In The Realm of the Senses (Ai no corrida). I’ve just looked over some calendars from the mid 1980s and was surprised to see how much film I was ingesting. There may have been a limited amount of TV channels in those pre-satellite days, but there was no shortage of films. Auntie Beeb and new kid on the block, Channel 4, had a public monopoly access to the film market. VHS was established and DVD was on the horizon. But to be able to see what your heart and soul desired, necessitated a trip to the picture house. It’s good to see there are plans afoot to design a Scala book, as the cinema produced lovely posters listing their monthly features. I usually hoard memorabilia, so I can’t account for the fact that I don’t have a single calendar month from my membership of the Scala. Perhaps it might surprise you to hear that I really can’t watch films anymore. I rarely go to the cinema. When you are in the business of producing art, there seems to be little time and perhaps inclination for seeking out art in your down time. Maybe it was also studying Film and Literature at the University of Warwick for 3 years and the celluloid feast we had as students, watching each film twice for close textual and semiotic analysis and which also included us projecting the 16mm prints sent up from the BFI. After ingestion, overdose?

While I had an eclectic taste, enjoying the classic narrative joys and happy endings of Hollywood cinema, it was the European art house movies that really tickled my fancy; although they did on occasion stretch your patience; the 317 minute cut of Bertolucci's 1900 seen at the Curzon Bloomsbury springs to mind. In the 1980’s, the work of two artists shaped my aesthetic outlook and personality: Derek Jarman’s gay-punk sensibility that pricked the constricting norms of Thatcherite society; and Andrei Tarkovsky’s metaphysical exploration of memory and haunting use of landscapes.

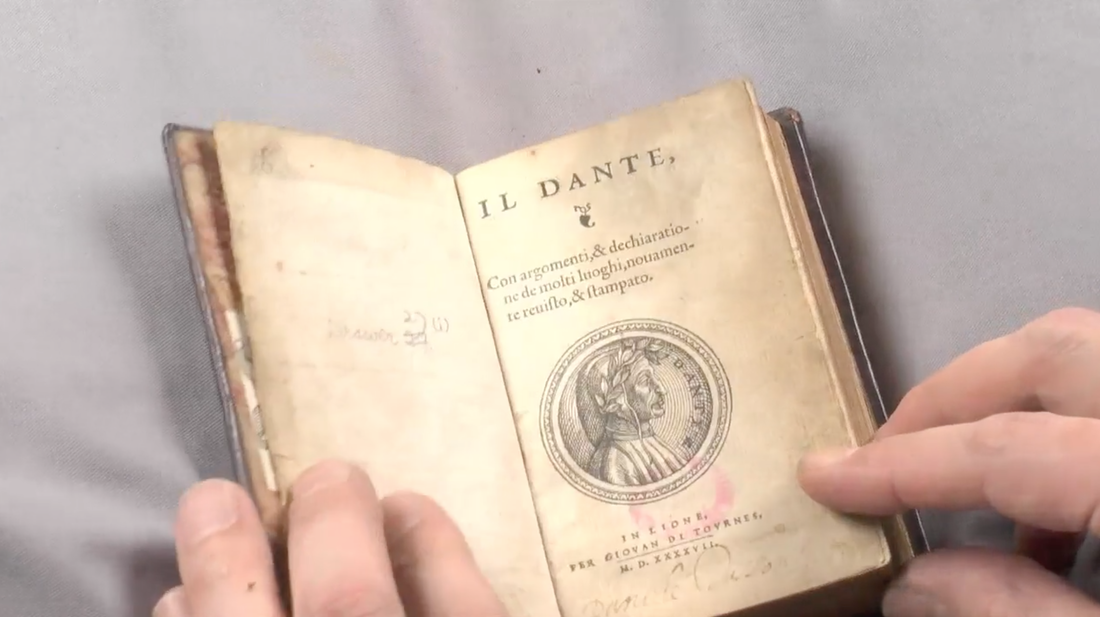

I had to write an essay to get into Warwick University (in addition to A level grades AAB and a medical examination!) That essay was on Derek Jarman’s The Angelic Conversation which I saw on both the cinema and TV in 1985. The film was a jittery and sensual evocation of Shakespeare’s Sonnets as read by Judi Dench. It was set in a timeless landscape of grainy, every changing palettes of muted colours that condemned men to drift and brood and lock horns in the slow-motion ritual of love and sex. The Sonnets themselves have an enigmatic quality that has divided scholars; the first 126 addressed to a man and the last 28 to the dark woman.

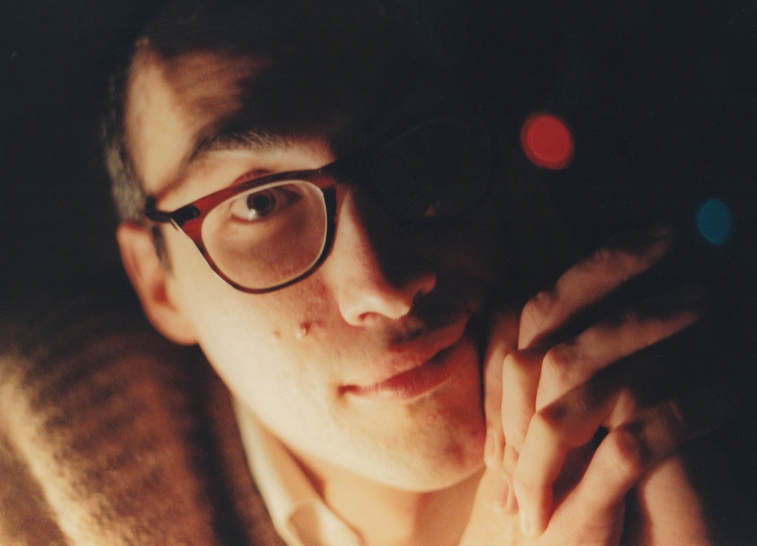

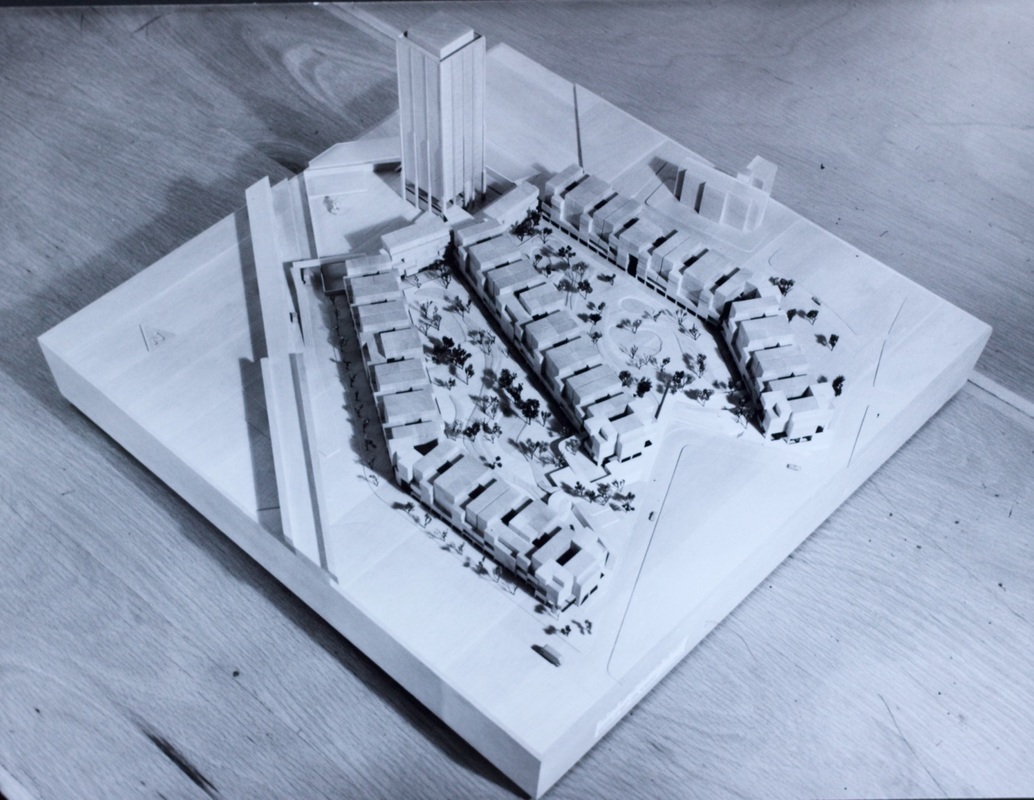

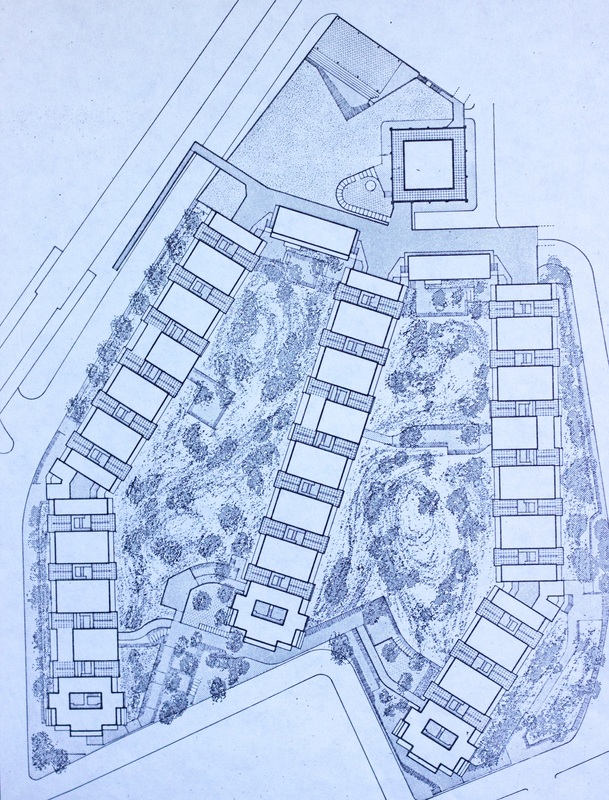

Abbey Fields, Kenilworth 1989

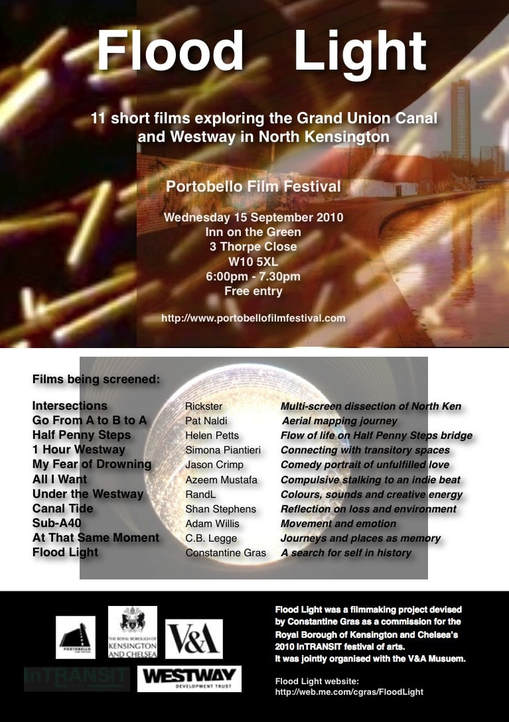

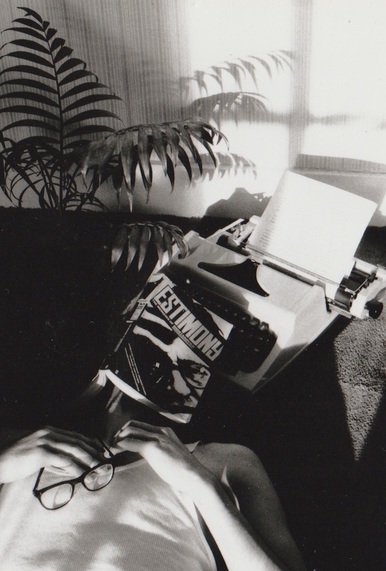

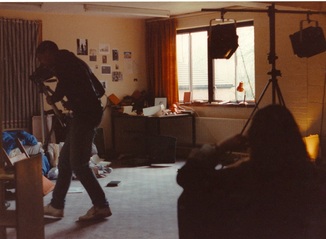

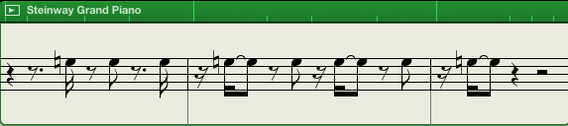

As a young man, dressed in my 1940’s suits, I seemed to wander in and out of both Jarman’s and Tarkovsky’s filmic landscape. I even had a dramatic film, This-That, inspired by my personae and made by fellow student and dear friend, Jacob Barua. That film was recently digitally remastered and there are plans for a sequel that updates the character into the 21st century. I better watch these spaces. After Warwick, I attempted to forge a part-time career as a stills photographer and eventually made it behind the film camera. Apart from several minor juvenilia works, my first real directorial effort was Flood light (2010). This was made for InTRANSIT festival of arts and I made a connection with the V&A Museum, later becoming one of their artists in residence. Although it wasn’t consciously conceived of as such, this film employed the strategies of what we might term the art film. The film used dialectical montage rhythms around the Grand Union Canal and the elevated road in the sky, Westway (A40). It fused together autobiographical elements (school books, carpentry tools), archive photos and film from the 60s and used period locations at the V&A to meditate backwards and forwards in time. There was no narrative drive or dialogue to guide the viewer in interpreting this stream of visual consciousness. A dripping soundtrack connected up images from beginning to end. It was a film about my urban identity in North Kensington. How I was able to intellectually and emotionally connect with water and concrete built environment. It is a film that has been aptly screened under elevated motorway roads in East and West London and in the Whitechapel Gallery. It has all the sins of a first film, but is probably my best work thus far.

Poster for Flood Light, 2010

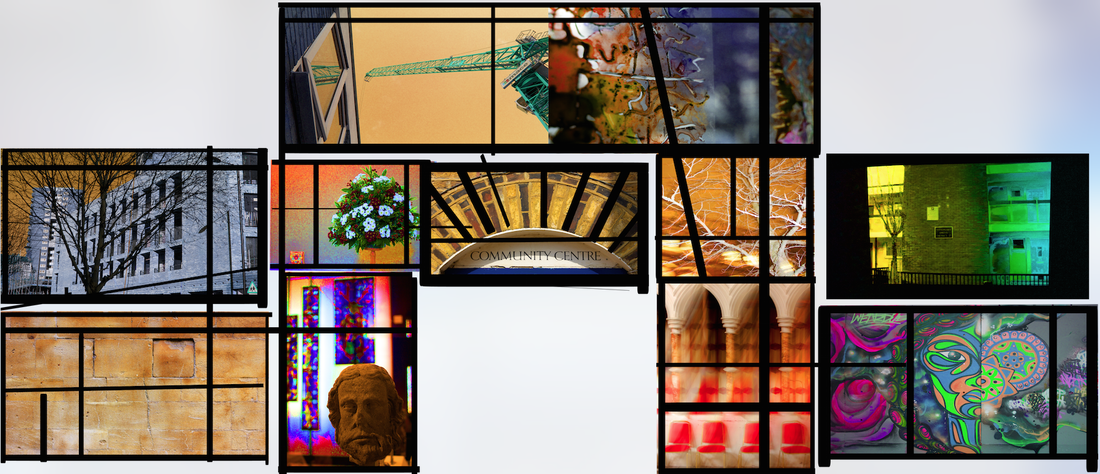

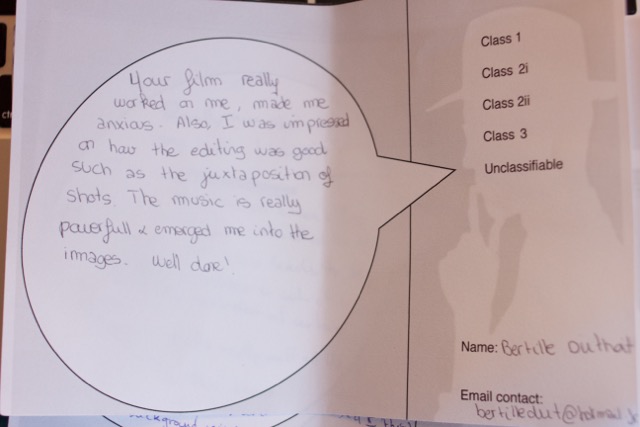

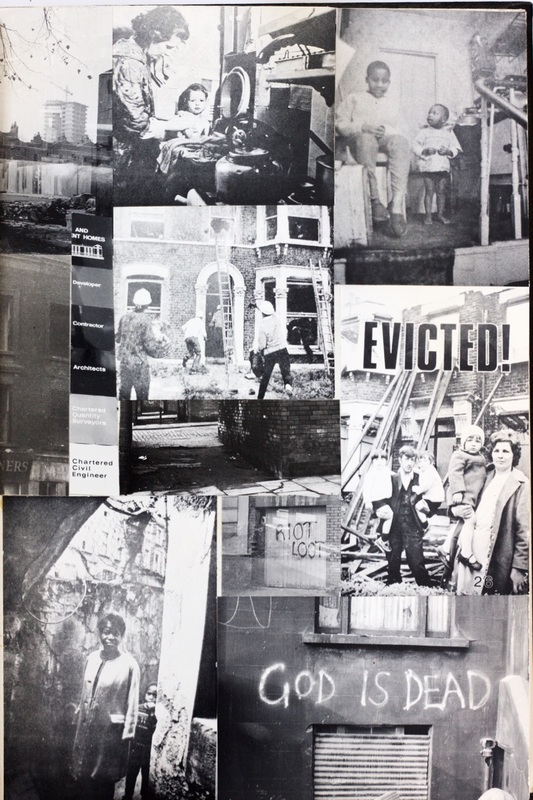

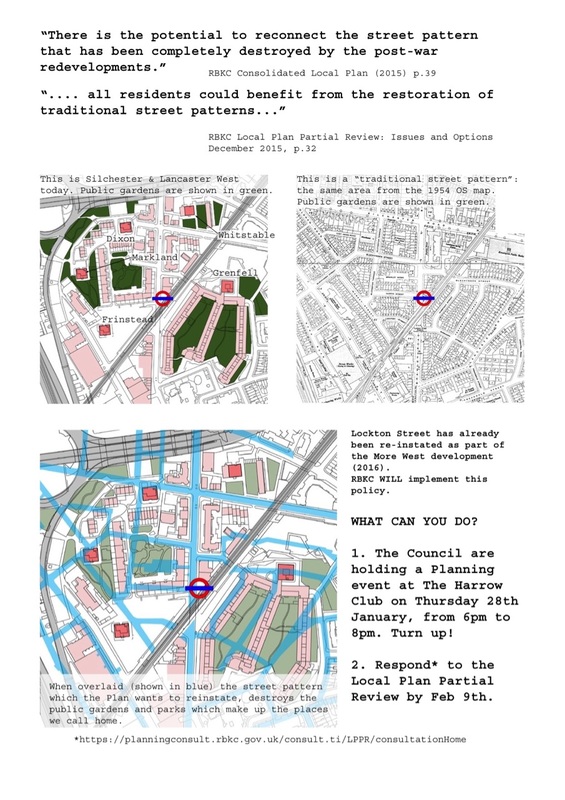

In addition to making films, i have also curated film programmes and these have been useful platforms to support other emerging filmmakers. These are not exactly double or triple bills, but short films screened one after another and all inter-related on a specific theme. Flood Light was screened as part of a programme in which I invited other film makers to journey with me across the landscape of North Kensington. Local residents were also supplied with film cameras and edited their films at the V&A's Sackler Centre for Education. A panel from the V&A, Westway Development Trust, British Waterways and RBKC Arts selected the Best Film submitted for Flood Light and this was Intersections by Rickster. Henrietta Ross from British Waterways commented on this film: "I was very impressed by this. I thought the format worked really well conveying a great sense of movement. The sense of a journey was represented well, as was the great variety of activity going on around the location and the varied perspectives the location offers on West London life. I thought the different views were matched really effectively with a great eye for detail. The combination of colour, movement, stillness, nature and community activity was really engaging." It was also a pleasure to see an early film from film maker Azeem Mustafa who has since gone on to specialise in martial arts film. Simona Piantieri has also subsequently produced exceptional work. I particularly like the documentary film she made with Michele D'Acosta called A House Beautiful (2017). I followed up Flood Light with another curated programme called West Ten Fade Out (2013). This was able to showcase the film making talents of Dee Harding and Sandra Crisp. When I was the V&A Community Artist in residence based at Silchester Estate, I put together another selection of short films called Home Sweet Home (2014) around the issue of housing and domesticity. I particularly like sourcing archive films and using extracts that provide ironic or amusing contrast in the programme. I used two such extracts in Home Sweet Home and they are animated films from the Wellcome Collection. The Five (1970) is by Halas & Batchelor and opens with a young girl coming home from a party and going to bed; but her pooped toes take on a life of their own. The opening 7 minutes of Full Circle (1974) has exquisite art and animation by Charles Goetz that shows the development of city living and the possibility of over-population in the future leading to the collapse of civilised life. I have also tried to use film to connect residents with the history and social issues in the area in which they live. One example was a free screening I arranged of Leo The Last at the Gate Cinema in 2015. This was and is a profound film that connects with Lancaster West estate and Grenfell tower. I even wanted to screen this on Lancaster West estate for residents and the housing authority but circumstances conspired against that. The residents were locked in dispute with the Tenant Management Organisation over the Grenfell building works. I was commissioned by the TMO to make a short positive film of this regeneration taking into account the residents perspective. The film I delivered was a one hour long film completed in 2016 and called Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate. It was based on the life stories of seven residents. This was not a straight forward documentary with people speaking to camera. It is voice over set against the architecture of the estate. Although that film was deemed not fit for purpose by the TMO and fell into a state of limbo, I know that it really bonded me with residents in the community who have since become good friends. Hopefully it will have a proper screening in the near future. I have other footage that is strictly reserved for the police investigation. It isn't a good feeling to have art work that is delicately tied to the tragic events of Grenfell. There is no awe, just the shock.

2015 Poster for programme of short films, including rough cut of Lancaster West - The Forgotten Estate

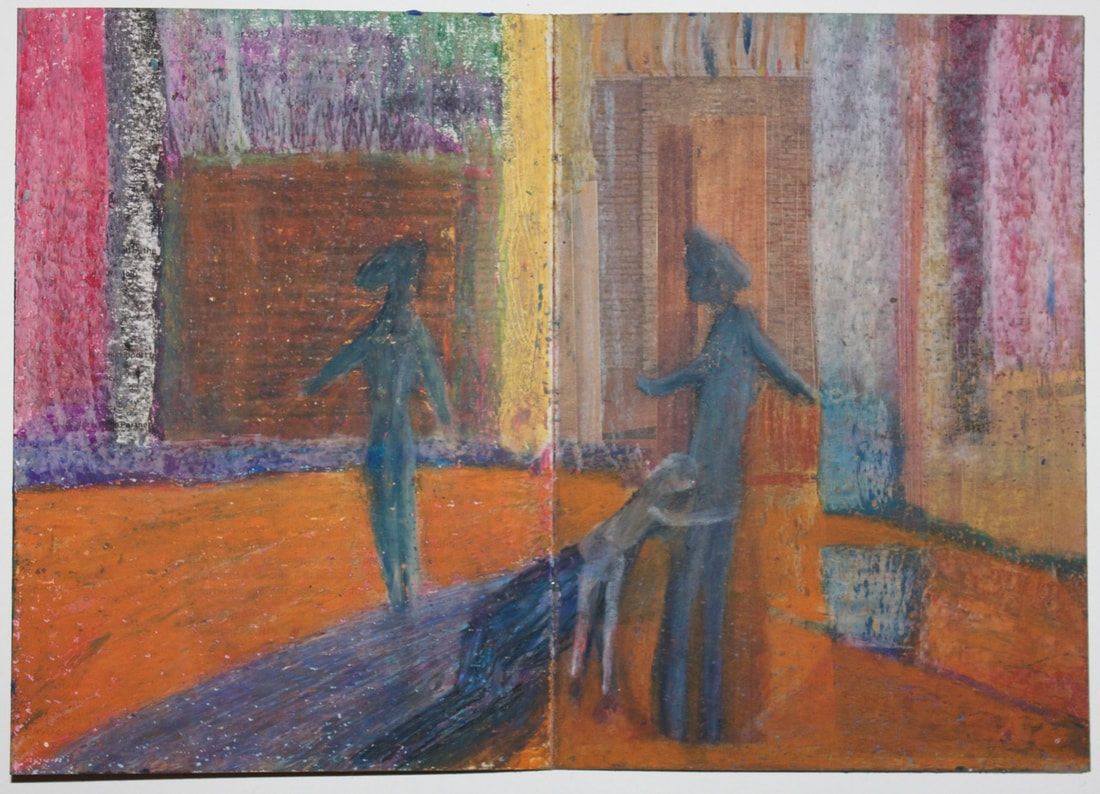

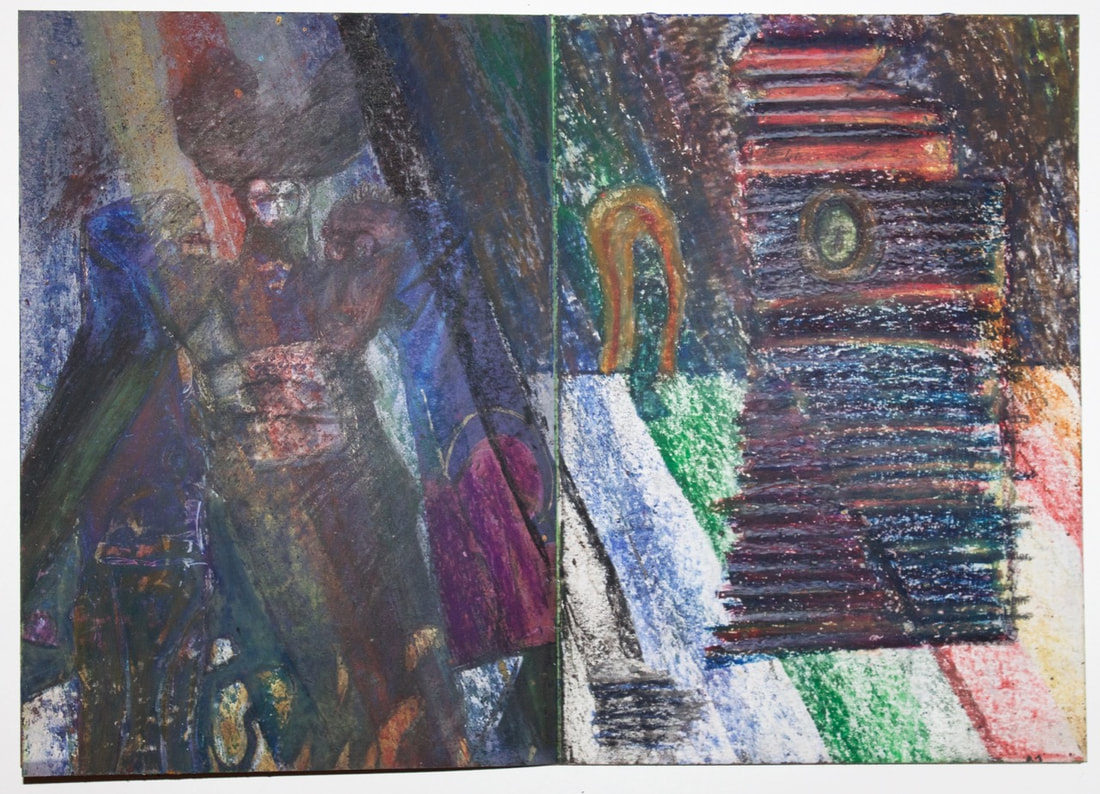

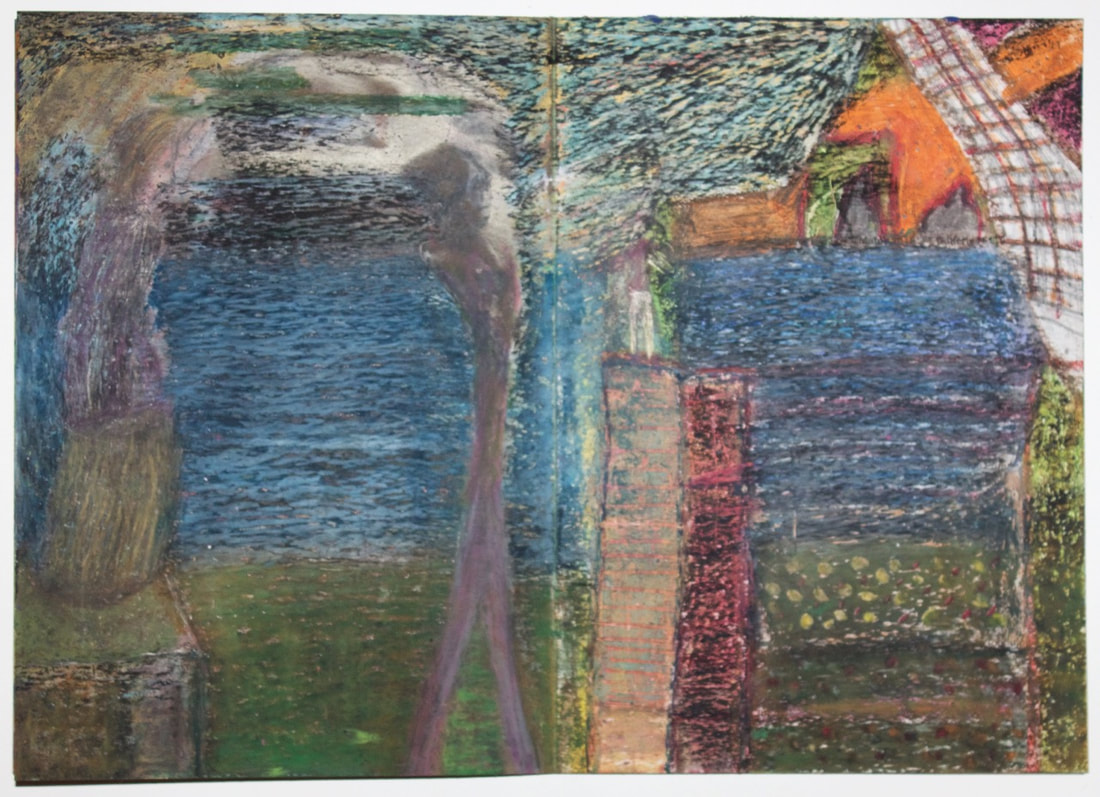

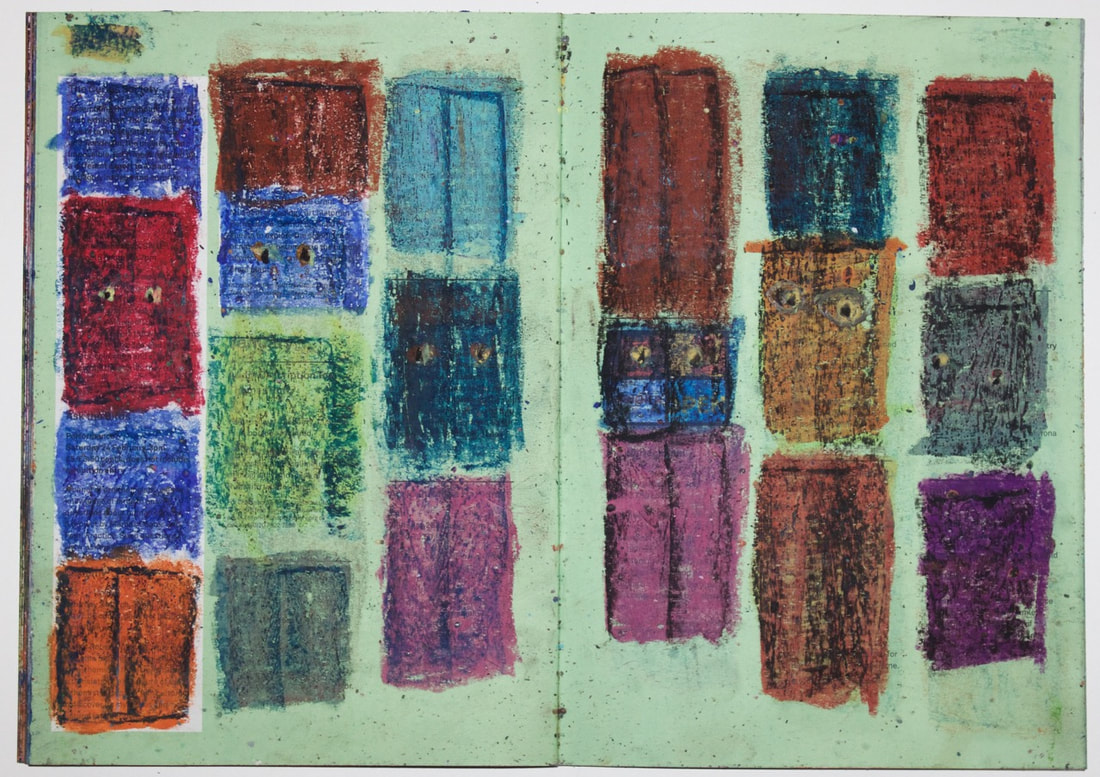

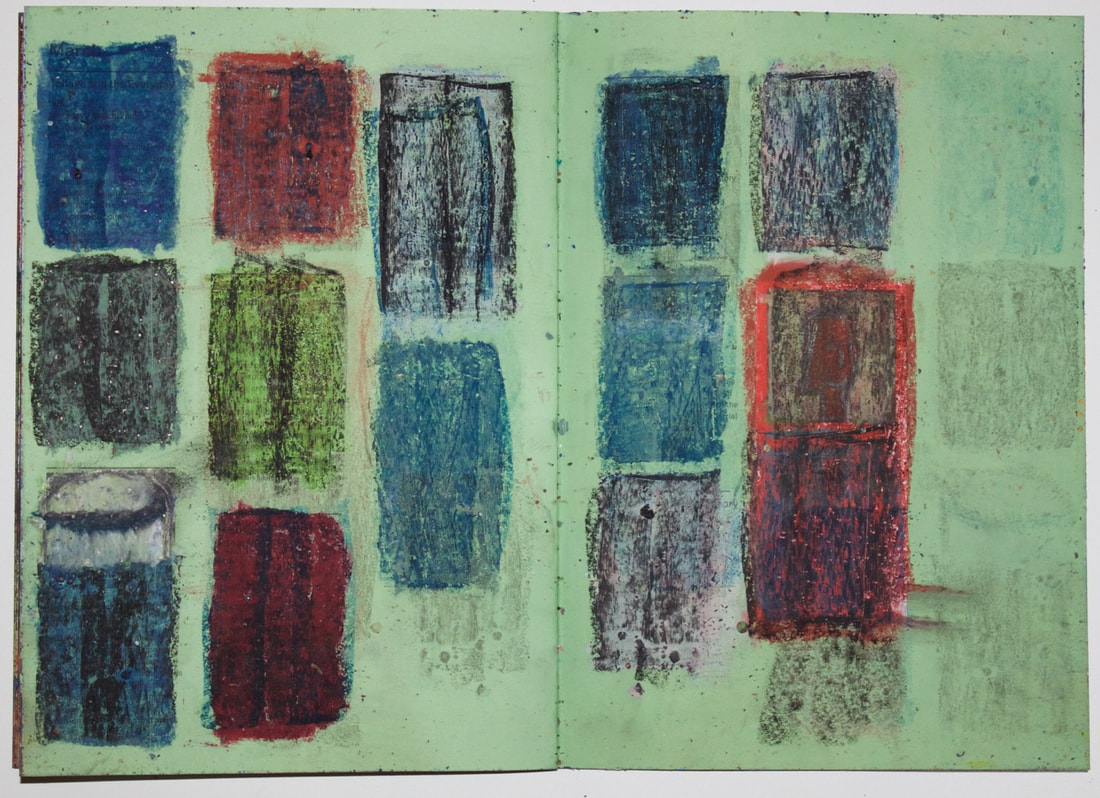

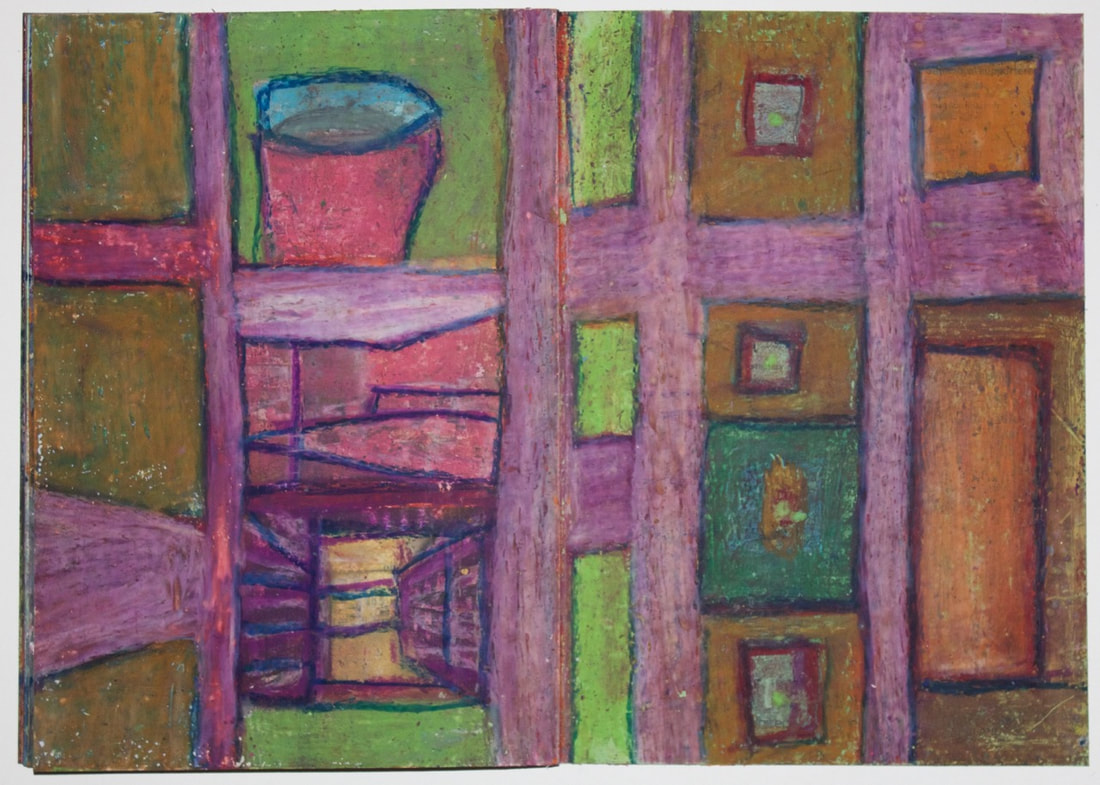

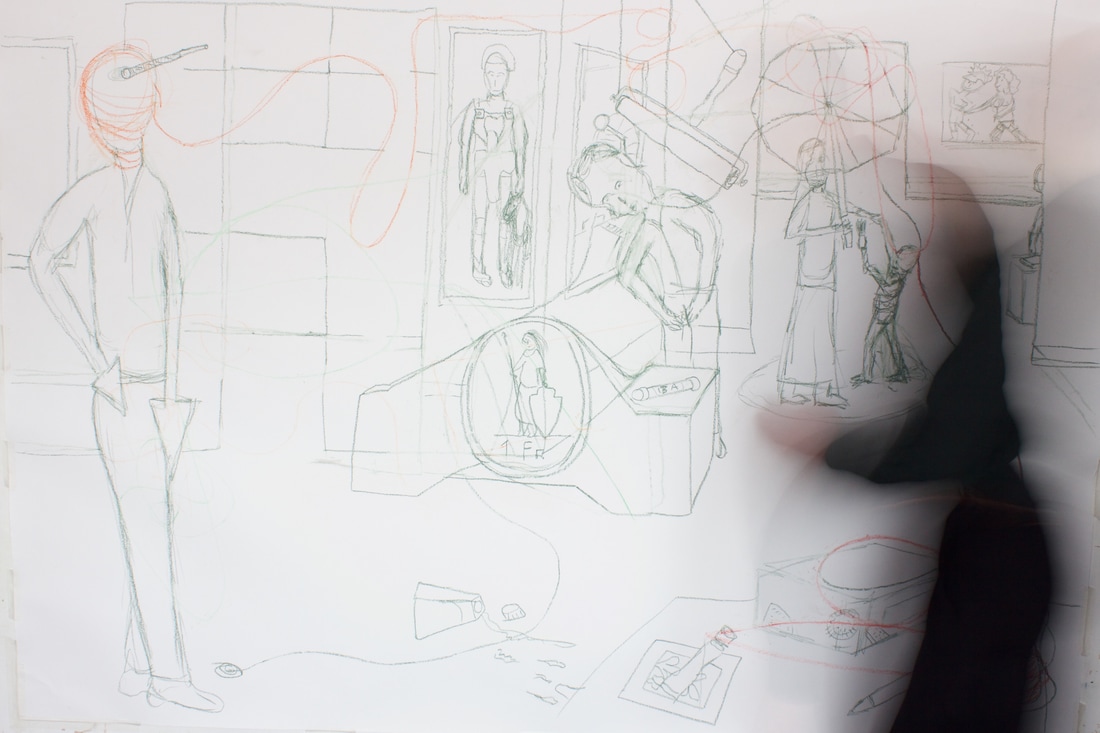

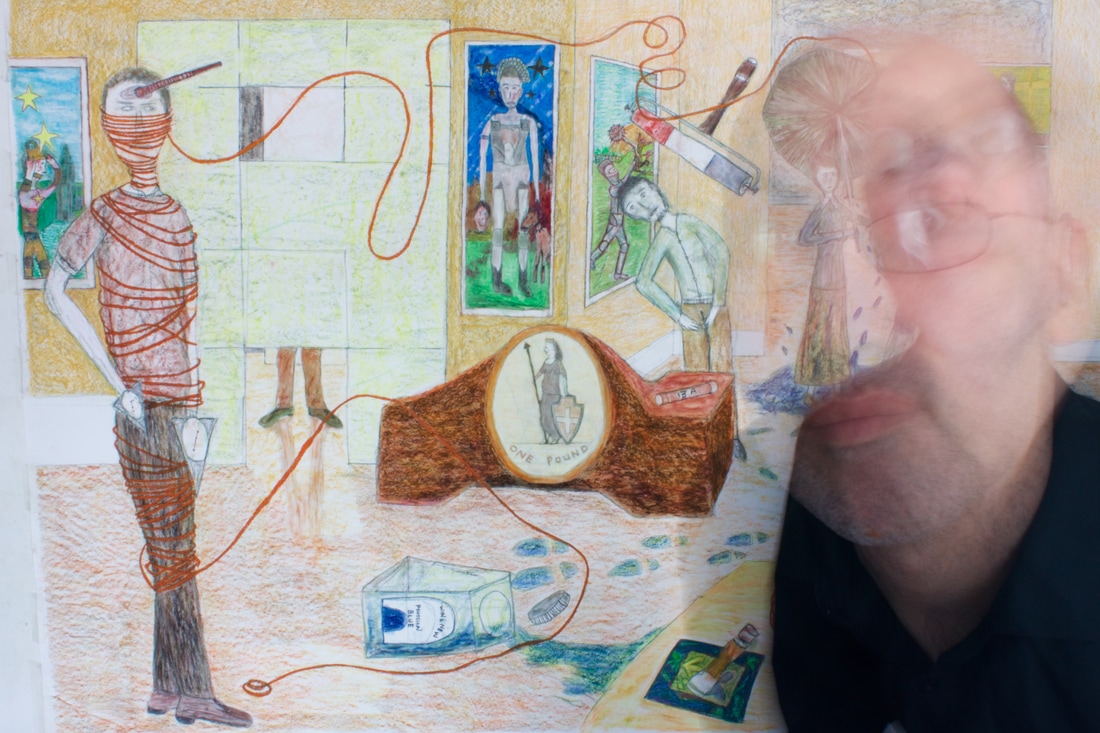

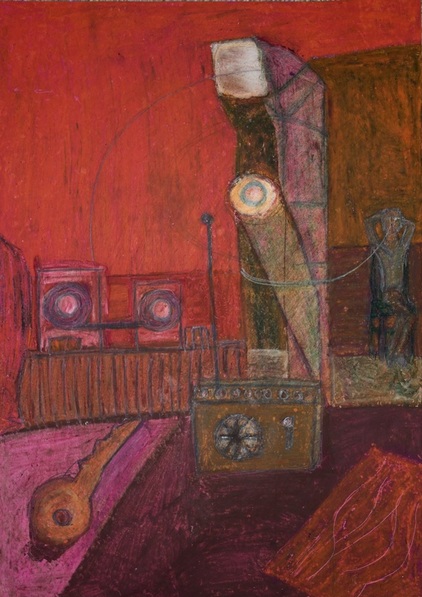

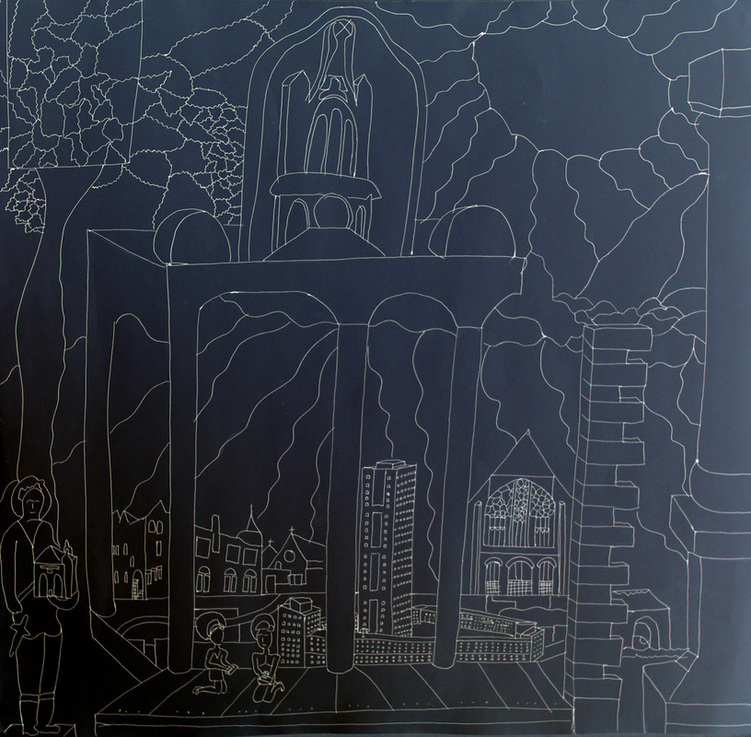

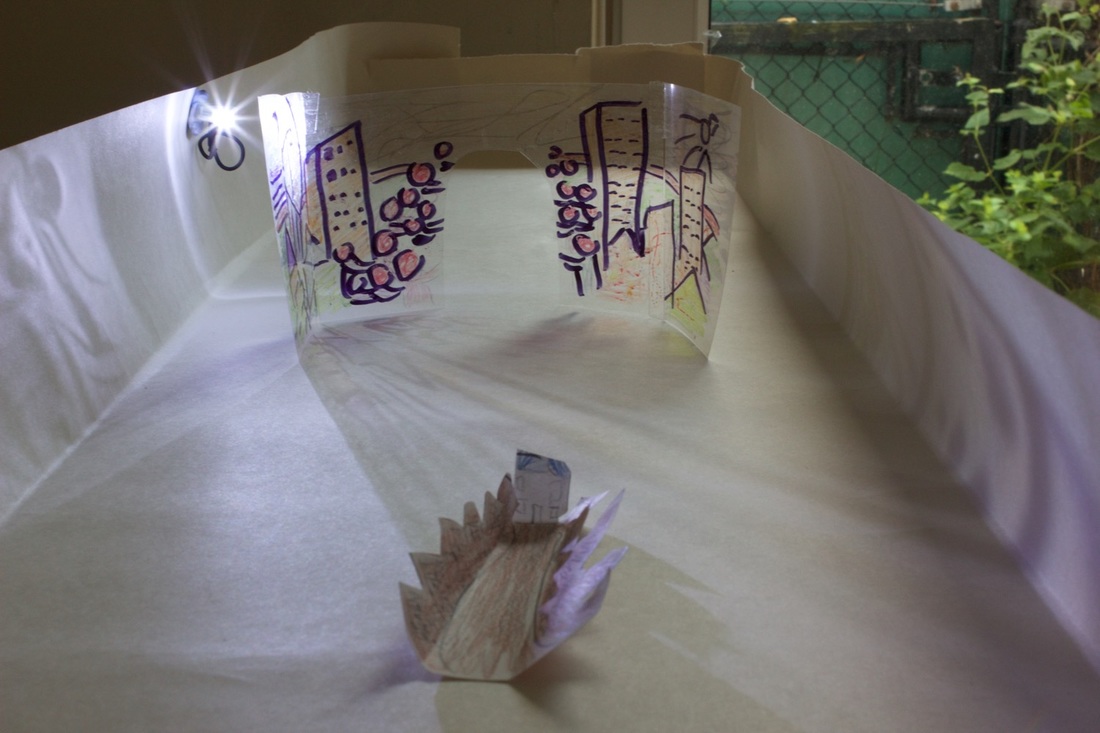

As I think of film, I draw and vice versa. I visualise films in my mind and these invariably start off as storyboard type drawings. The reality its that most films never get off the drawing board. But with the combination of drawing and writing, perhaps I can release some of that pressure cooker tension of being a multi media artist whose main aspiration is to make films. Let me conclude this blog by visualising a meeting of sorts between Derek Jarman and Andrei Tarkovsky on Hampstead Heath. Nothing is impossible in art and film. I need you to imagine that both are simultaneously drawn to the area for the making of a film.

Fade in.

A young man materialises out of the bushes, doing up his trouser belt, exhilarated, out of breath. A trickle of blood flows from his lips. Tarkovsky screams in Russian: cut, cut! The actor has wandered into the wrong film. A grounded helicopter rotor blade whips up a force of air onto the billowing grass and almost topples over the camera. Cut, cut. The production assistant rushes over to the helicopter. The timing is all wrong and aviation fuel is expensive. Tarkovsky curses under his breathe. Then looking at the bemused actor and the apologetic pilot, he starts to giggle and can’t stop giggling. The crew look at each other unsure whether to laugh. Tarkovsky motions for the actor to stand still and for the cinematographer to train the camera on him. Smiles all around and the actor looks up at the sky. It is a bright cloudless summer evening sky. A few rain drops start falling.

Cut to Jarman lining up his shot on the other edge of the heath, near a pond. He has torn up the script (that didn’t seem to be working) and is waiting for something to happen. His actors have got lost and a search party has been sent out. The rest of the crew have gone off for a tea break. A woman in her fifties dressed in a flowered dress walks into shot and sits on a log in the distance. She catches Jarman’s eye. He goes over and speaks to her. Hello, are you waiting for someone? She shakes her head in a combination of yes, no and don’t understand. He tries again. Would you like a cigarette? She nods and takes one. While lifting up the fag to his match, Jarman notices a raw burn mark on her wrist. Jarman wanders back to his camera. He zooms onto her. They hear the sound of a helicopter in the distance. She looks up in expectation. She appears to be acting. Jarman thinks she looks Eastern European, maybe Polish or Russian. He starts filming her as she turns her gaze to the pond and the gentle ripples on its surface formed by the wind.

Fade out.

0 Comments

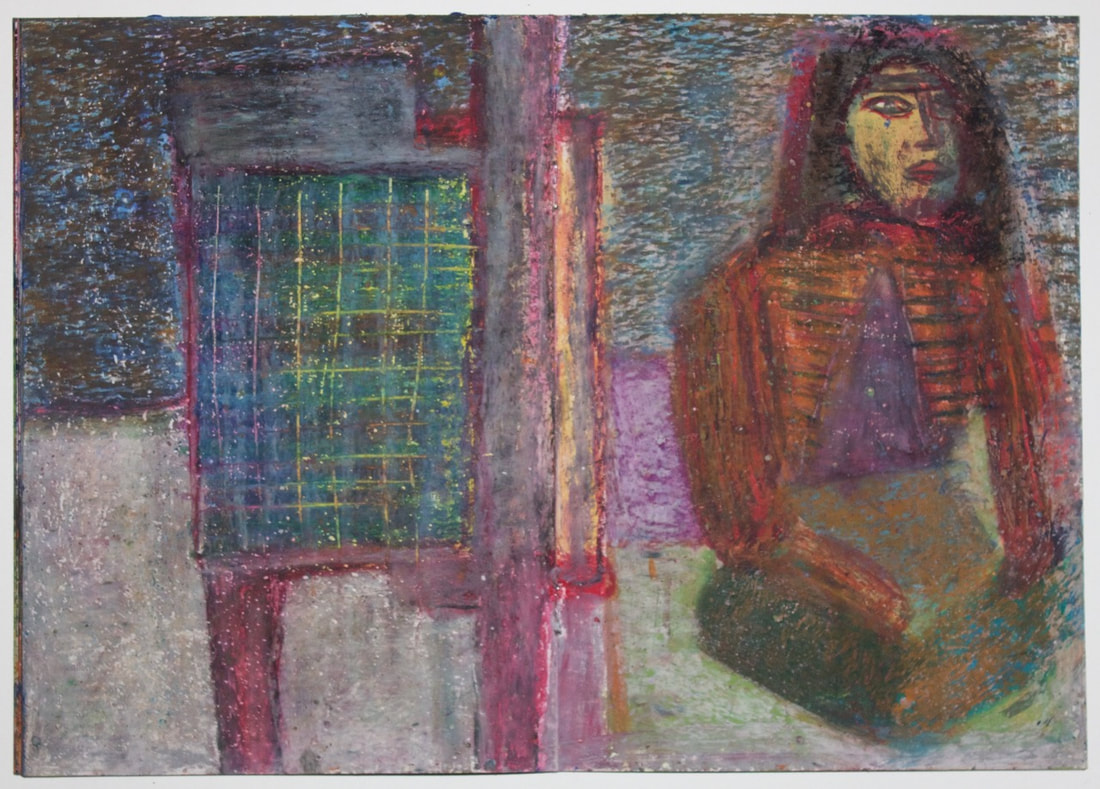

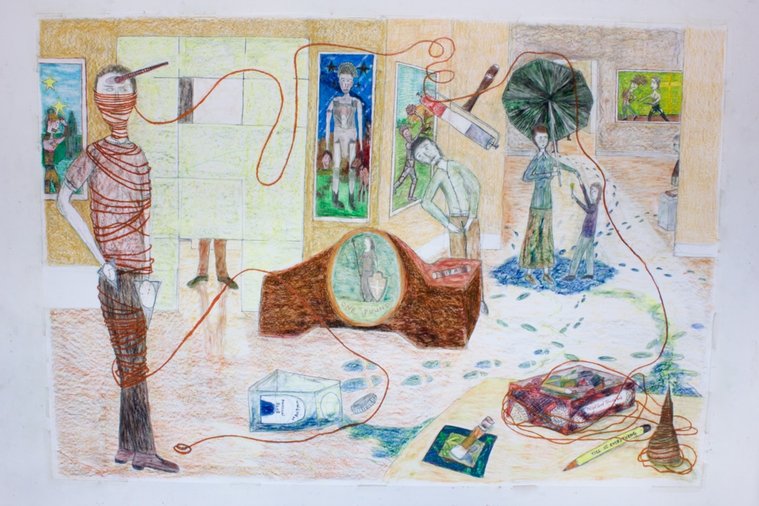

In A Lonely Place: once, twice, three times. Acrylics, 16x20 inch, 2000 The Lusty Men (1952) Directed by Nicholas Ray. Starring: Susan Hayward, Robert Mitchum, Arthur Kennedy. Warning - plot spoilers! The extensive cuts made to The Lusty Men indicate that RKO studio was dissatisfied with the film. When premiered in England it was seen as a very American subject matter and because it didn’t do well in the U.S. there was a possibility for further cuts. The film is also not firmly anchored to any storyline. It is more wandering and discursive in tone. The sections that include the character Booker Davis, played by Arthur Hunnicutt, were cut for the British audience; these scenes are there for the ideology of the rodeo world being portrayed and as an exploration of character and not for the plot. The film is almost anthropological in terms of locale and character with no real narrative. Only one film critic, Manny Farber, registered any of its qualities. The Lusty Men has subsequently emerged as one of the highest in Nicholas Ray’s oeuvre. It is a modest film that looks ordinary at first glance but has more unusual qualities in many respects. The Lusty Men was made under ordinary circumstances but is not a streamlined, efficient production. It was the producer’s idea to film the rodeo and to ensure the availability of film star, Susan Hayward who gets the top billing. It was conceived of as a Susan Hayward movie who was only available for twelve weeks of filming and this was not during the rodeo season. The film went into production with no script and this was a common feature for Ray’s films. The whole film was made in the studio with the rodeo shots filmed by second unit associates. The film script was improvised after the opening setting. At a late stage of filming, it was decided that the film should end on Robert Mitchum’s death. Everything in the film prepares you for the bust up between Robert Mitchum (playing Jeff McCloud) and Arthur Kennedy (Wes Merritt) and the resultant death and “happy ending”. This fits into the norm for Hollywood films but because Mitchum's character is almost suicidal the resolution is not a problem. Ray reckoned the decision to kill off Mitch lost the film a couple of million at the box office. The story used in the film is a standard success story. This is a regular formulae in film and television and also in stories about sports and entertainment. A young man of talent is trained by an old timer. The young man goes on to achieve success but loses his roots and becomes arrogant. This arrogance leads to humiliation. The resolution involves him undergoing a change of behaviour. But the Lusty Men does not tell this story. Instead of having the rising star as the central figure, Ray focuses on the has-been side kick (Mitchum) and his emotions. The rags to riches story yields another story. It is about Mitch watching another guy have the success he once enjoyed. It has an elegiac quality. Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas make for interesting comparisons. They invariably play characters who are going to be defeated. Douglas has a spectacular downfall while Mitchum’s characters usually register dejection and are mournful. Mitchum is often the fall guy in film noir. In The Lusty Men, his Jeff McCloud character is a wistful country boy of limited intelligence. The role is not a huge departure. But what is unusual is one element in the plot; the story of the hero who consciously wishes the destruction of his best friend’s marriage. This is never seen in 1940’s films where a strict Hays Code and respect for marriage is observed. (Ray said to V.F. Perkins that it was just so natural and normal in the film, how could the censors object. You can get away with things by sheer modesty.) The originality of the film lies in the presentation of the character of Louise (Susan Hayward). This is one of the most interesting portrayals of a woman in Ray’s films and is unusual. The romanticism and the sentimentality in the film is attached to the macho world of the male characters. The film is acute about the pain of a macho rodeo life to both men and women. Hayward as Louise Merritt is a calculating woman. She is clear sighted whereas the men are romantically deluded. She is realistic about what to get out of life and with whom. Louise is not prepared to give up her life in the face of the male vanity being displayed in the rodeo world. She is a woman controlling her emotions to get material aims. A female character who displays this in a Hollywood film is usually presented as a schemer or villain; one thinks of Barbara Stanwyck. These are not objectives that are stereotypically ‘womanly.” She never talks about children or family. She doesn’t want to work in the “tamale joint.” This is a fresh interpretation of a female character. Another major aspect of the film is showing codes of masculinity which are presented almost as a theatrical show. The wildest show on earth is not the rodeo but masculinity. The film is successful in making rodeo work not as a lifestyle but as a resonant metaphor which harmonises the presentation of character. The rodeo is about capture and asserting yourself on the past. There is a constant repetition of imagery in the film. At the very ending, after Mitch’s death, a new man enters the rodeo world and there is uplifting music as the film ends for the umpteenth time. The characters are looking for “something they thought lost.” This is not conveyed in the reality of farming where arthritis and the hard labour of tractors are the norm. These have nothing to do with bronc or bull riding. As Wes McCloud becomes more involved in the rodeo, it is not jeans, but the leather rhinestone image that appeals to him. More and more, it is the Roy Rodgers cowboy singing image and not someone dressed for work. The song on the flag. “Old Glory”, and Mitch’s return to rodeo is an attempt to show his past glory. It is an ironic, repetitive, dehumanised rodeo. Ray expressed aggravation that the cruelty involved to get animals wild could not be shown in the film. Within the structure of the film, there is a dividedness which is common to Ray’s films. Here it is between the nomadic lifestyle and one of stability. In They Live By Life (Ray’s 1948 directorial debut) this is evidenced in the lovers on the run and Bowie wanting money to hire a lawyer to prove he is innocent of murder. In The Lusty Men it is about initially wanting to get money to buy a ranch. But Wes is seduced by the glamour and success and instead he buys a caravan which is the perfect 1950s symbol of nomadic lifestyle. In one sequence, Louise is shown sleeping and the camera tracks back to reveal her seated in a car. This is an image of her floating down a street. This theme is strongly registered in the character of Jeff (Mitchum). He is the centre point of this divided world, caught between the nomadic and settling down. This is best illustrated when he first returns to his old home ranch and rediscovers an illusionary security. The Lusty Men is one of the best triangle movies. It is all done modestly and treats this theme sensitively. The film refuses to makes its denouement tragic. The pain it is about is too ordinary for tragedy. The frustrated lives the characters lead are ordinary and we are never tempted to believe that Louise has spontaneous love for Jeff that is going to blossom. She is aware that what Jeff offers as a rival to her husband - stability, security and an unspectacular life - is never going to materialise. The relationship between Jeff, Louise and Wes is unstable. Both Jeff and Louise stand in a parental role vis-a-vis Wes. Louise is a mother figure as well as a wife: taking his boots off; the way Wes sits on the draining board wiping up the dishes. “He ain’t two years old and I ain’t his mother.” Jeff enters as a paternal role training the younger Wes. But when Wes is drunk in one scene, he comes up and pushes himself on Jeff, who then punches him down. They are almost forced into the role of a couple because of Wes’s character traits. Then Jeff has to live with Wes as an adolescent. When Wes discards his advice, Jeff is left alone. One character always feels outside this triangular set up that is reshifting in terms of dramatic relationships. There are a range of other characters who offer models for what the rodeo way of life offers. For Louise it is Grace: “Rodeo will make you an old woman before your time.” For Wes, it is Jeff and Buster Burgess, the latter offering gambling and drinking. Also Booker who is senile, almost mentally incapable of keeping up with the costs and demands of life. None however offer a model of success. Jeff has had success and learnt things. But the movie is consonant with other Ray movies in showing Jeff as simultaneously wise and informed about the ways of the rodeo, with a homespun philosophy where you “eat a little dirt if you have to,” while also substituting guts for good judgement. When it comes to the crunch, he is incapable of good judgement. What he needs and most feels, puts him on the path to catastrophe. Is it logical that his comeback is both a success and a death accident? But this goes with the modesty and unspectacular themes of the film. Jeff (Mitchum) is not a has-been and a wreck. He is not old enough to be a wreck. The death of Jeff is the film’s final form of disaster. Masculinity means you have to find out if you can still do it. You only find this out when you die. This is what the film says about competitive virility. The image of Jeff and his fate as an action image is one of eloquence, poetry. The film puzzles around images of mastery and control. The pride he feels is offered at the beginning of the film. Jeff is standing above the bull in the pen and the shot is composed as a stable frame. Thirty seconds later, the sequence of shots are wild and subjective. The hand-held camera is almost indecipherable. The stability and claim to control is undermined by Jeff’s fall. As an action image this is morally and philosophically pertinent to the themes of the film. 26/02/87 Lecture delivered by V. F. Perkins, University of Warwick, Film and Literature, Movies and Methods : Forms of Analysis 82 x 56 inches. Oil pastel, pencil. 2017. Poem to a drawing Are we walking down a corridor in the National Portrait gallery? Walls lined with the great and good who have killed and conquered. This is all rather tiring and I am looking for somewhere to sit. Commotion in a room ahead, left or right? A gust of wind blows us into the Euro wing. We see a mother and child with candle and umbrella. A man checks his flies are zipped. Above his head, a tricolour ink roller in suspended animation. On the ground, footprints of Prussian blue. Centre stage, chaise lounge. What is going on? Can we sit here? Maybe in the next room, next to a woman and her copy of J. G. Ballard's The Atrocity Exhibition. In front of a painting of the British Prime Minister getting fruity with the American President. Hold on! Is that Robert Rauschenberg trapped in twine from a plumb bob? He appears to be pointing backwards and forward, one hand to 1974, the other, 2019. Can we trust an artist to TELL US EVERYTHING about this space within space That has spilled out from a box labelled Highland Shortbread? Where can I sit? My legs are killing me. Notes to myself This was sketched immediately after visiting the excellent Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at Tate Modern and during the United Kingdom government's formal notification of withdrawal from the European Union. This was also the week when The Daily Mail newspaper on March 28th featured a photo of Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon with the trivialising head line: “Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!”. On the same day, a new 12-sided £1 coin became legal tender across the UK. Pondering all these matters, I started to sketch a scene using Robert Rauschenberg as an enigmatic muse. His free and easy approach to materials, for example, building an umbrella or fan into a painted surface, had me thinking about how to use everyday objects as part of my art practice. I turned to a biscuit tin in my studio. I don't know why I started to collect objects in a biscuit tin or how long they have accumulated (more than a decade now), but this box with random objects ranging from coins, fuses, tea coaster, plumb bob, pencil emblazoned with "Tell me everything," was raided for inspiration and incorporated into the drawing. This was my equivalent to Rauschenberg's "combine" although I have made no concession to three dimensionality. There is added irony in that the box has a culinary connection with Scotland; a nation destined to have a falling out with the English over the issue of falling out of Europe. All these objects and related ideas came tumbling out of the box and into the composition. Some other allusions for the cultural critic to register:

What would you do? Imagine your neighbour Heinrich Boll had left you a spare key and instruction to water the house plants while he boarded an aeroplane to collect a Nobel prize. Would you steal inspiration from the draft in his typewriter? Or Max Opuls had entrusted you, his dear friend, to retrieve a roll of film from his house; the one the censors didn't see in La Ronde. Would you leer at the said negative being held up to a bright light source? Kathe Kollwitz had to nip out to buy some milk and bread. Mischievous thought of adding a smiley face of ink to the desolate image in the printing press? The aforesaid fantasies were inspired after listening to an interview Holgar Czukay gave in the early 1990s on the Radio 3 programme, Mixing It. He recounted how as a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1968, he sweet talked the secretary and gained access to Herr Aladdin's electronic cave. Holgar was able to record his debut album, Canaxis 5, with the studios impressive tape recorders looping together his interest in Musique Concrete and ethnographic folk recordings. Not all studios live up to their profession. In point of fact, given the relative poverty of artists, they invariably have to beg a shed, borrow a broom cupboard or steal a loft. I have only had one bonafide studio. This was once a 1960s council flat (bedroom, living room and a kitchen) and came with the responsibility to practice community art. An author might build a studio around the typewriter on an heir loomed desk or a poet might dream on a hammock in the garden. Maybe virtual studios will one day be the norm for web based artists. The creation of an avatar, perhaps even adopting the identity of the Germanic artists I have already listed. Expanding on this chain of thought -what about that elusive key to the artist's mind?

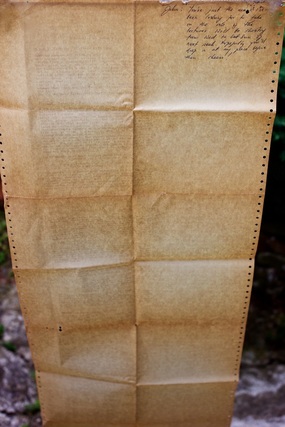

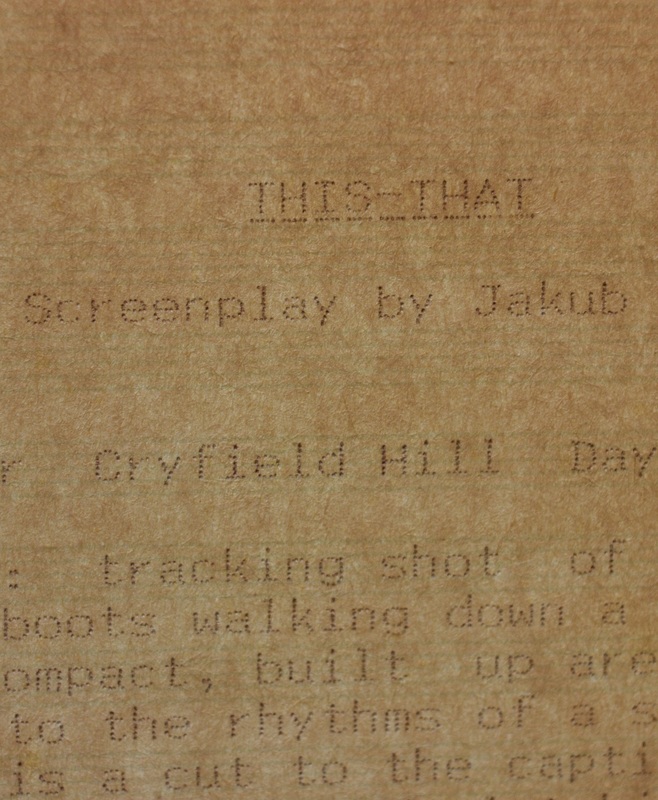

Script for This-That by Jacob Barua. Printed on continuous feed paper, Warwick University science block.

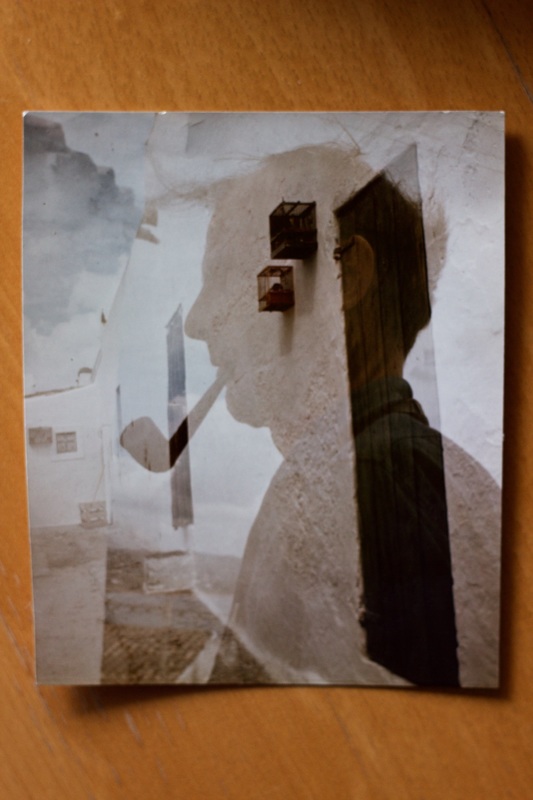

I am navigating back to 1989 and the University of Warwick. My fellow Film and Literature student, Jacob Barua, has handed me a film script and declared emphatically: you are the only person in the universe who can play this! I hesitated. Had never acted before. And then there was the troubled central character in the drama who seemed all too recognisable; forever on the edge of everything, nothing, relationships, art, politics. This begged the following question: Jacob are you taking the piss out of me or yourself? For a short period of time we seemed to swap identities. Jacob’s intense cinematic vision became one with my suited and booted persona. Jacob was going to use this short film to catapult him into the prestigious Lodz film school. But it was no plain sailing. No film production on this dramatic scale had been undertaken at the university where theory ruled the day. It meant sniffing out equipment and resources. After two weeks of filming, a mere two days were spend in the edit suite, using equipment for the very first time. I recall a few expletives. We had set the date of screening, one day after the final day of editing. A key animation sequence shot on 8 mm film only arrived on the day of the screening and had to be added post-haste, post end-credits. Thankfully this has now been re-edited into its proper place in the dreaming body of the film. We finally have the keys to the digital edit suite. It's only now after 26 years and working together again on restoring the fading VHS tapes, that we’ve got a new grasp on the importance of this film for us. Let me leave the final words to Jacob Baura who was recently interviewed about his Warwick experience. What on heaven or hell was he thinking about when he made This-That?

Jacob Barua:

"The reason I wanted to become a filmmaker, did not have that much to do with film per se. I had always been enthralled by Art itself in all it's aspects. I had been a poet, a musician, a painter, photographer, amateur actor, but probably loved literature most of all. Somewhat like a brat with his hand in a jar full of goodies, I did not want to let go of any of the Arts and decided that there was was only one vessel that encompassed all of them. The only way, in which I did not have to discard any, but instead fuse them, was through the glowing medium of film. I arrived in Warwick...by mistake. One of my obsessions when it comes to the written word is History. Right until today I often wonder whether I am a self made historian expressing myself and researching through film. Warwick conjured in my mind the mystery and glory of medieval times. I was convinced that the University of Warwick was located somewhere within the town of Warwick. In those pre-internet days, a major source of information were brochures. And the university's were filled with images of Warwick Castle and the old cobble stone streets. That was enough for me to decide, given that it was simultaneously the only university offering such a broad course encompassing foremost literature and then film. I got off the train in the quaint railway station only to be horrifyingly informed that the university was far away in some fields between Coventry, Leamington Spa and Kenilworth! I found the course at the university to be exhilirating in it's scope - exactly tailored to my needs. Great lecturers and given the small size of our department, an opportunity to bond with colleagues. The university also happened to probably have the largest independent Art Centre outside London, at the time. There was everything ranging from a philharmonic orchestra to to a cinema with plush seats and a sterling screen, to one of the best equipped professional theaters anywhere in England. Here I was active as a member of the Warwick Drama Society, taking on delicious roles for the duration of my studies. Besides, the university was a beehive of political activity, of all manner of shades. Of course I was aghast that the most prominent ones were for naive fellow travellers of all manner of totalitarian off shots. However the jewel of this mini-city was a massive library, with a salivating wealth of books that was beyond belief. This-That was the result of a deep inner need to encompass my entire experience as a student who had lived in different countries, cultural and political systems. At the same time I set to creating a time capsule to be sent into the future. All Myths were after all created by somebody, even if that was thousands of years back - so why not make one too, there and then, to be flung into an unfathomable distance? My inspiration for the main character was essential to creating a core, and this was based, at least in terms of the visuals on a readily available 'blueprint'. For I used Warwick's most enigmatic and unique real life student - Constantine Gras. He did not fit into any preconception - as he neither had the persona of a typical student, nor even one from any 'civilian' from our contemporary milieu. Here was Someone who seemed to have been historically misplaced, from a 'wrong' age. Like a potter I used him as my clay, to impose onto him a narrative, which I knew would jar when combined with his persona. So here was a man creating himself i.e. Constantine, whom in turn I was creating further. Layers of creation. One of the overarching themes is the struggle that each human has to undertake to find a space of comfort, to be able to be oneself, while struggling against the dominant societal forces. By comfort I do not at all refer to a personal one, but that of the Other. For the most crucial single question ever spoken for me, which forever thunders across all ages is; "Am I my brother's keeper?" We live in a world circumscribed by political correctness. The moment you challenge the narrative of the day, you are deemed fit for condemnation and rejection. In the case of the film, the character not only isn't ascribing to Modernity and the race to keep up with fashions both external and internal, but occupies a realm that defies the obligatory 'standards'. He is still both a reflection of the Ancient, Romantic and Future ages. Whether we like it or not from the beginnings of History, politics impinge on almost everything in life. That is why the culmination of the film is congealed within the incongruous figure of a young pyjama clad student who dares to take on the Rulers of the World. The selfish manipulators - the Daeduluses vs the selfless dreamers - the Icuruses. If I were to try to draw a circle; Sleep - Pyjama - Dream - the Impossible - Courage - Death - Eternity - Sleep.

The reception of the film, I will admit, was heart breaking. An outright regurgitating by the audience. Particularly so - when not even our lecturers or collegues could grasp or extract any meaning out of it. But this should have been expected, as it was intentionally put together in such a way as to defy conventional modes of film-making. And again, it was indeed a film made for Another age. But which one? Time will still tell.